Benner’s Philosophy in Nursing Practice

Karen A. Brykczynski

A caring, involved stance is the prerequisite for expert, creative problem solving. This is because the most difficult problems to solve require perceptual ability as well as conceptual reasoning, and perception requires engagement and attentiveness.

History and Background

More than 30 years ago, Benner began what she describes as an articulation project of the knowledge embedded in nursing practice (Benner, 1999). Her initial thrust toward further understanding of the theory/practice gap in nursing (Benner, 1974; Benner & Benner, 1979) became transformed while conducting the Achieving Methods of Intra-professional Consensus, Assessment and Evaluation (AMICAE) project, which provided the data for the widely acclaimed book From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice, abbreviated FNE in this chapter (Benner, 1984). Profound exemplars of nursing practices were uncovered from observations and interviews with clinical nurses during this project that demonstrated that clinical nursing practice was more complex than theories of nursing could describe, explain, or predict. This constituted a paradigm shift in nursing by demonstrating that knowledge can be developed in practice, not just applied, and signifying that practice is a way of knowing in its own right.

Two direct outcomes of the AMICAE research project were (1) validation and interpretation of the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition for nurses and (2) description of the domains and competencies of nursing practice. Benner’s ongoing research studies have continued the development of these two components that have been applied extensively in clinical practice development models (CPDMs) for nursing staff in hospitals around the world (Alberti, 1991; Balasco & Black, 1988; Brykczynski, 1998; Dolan, 1984; Gaston, 1989; Gordon, 1986; Hamric, Whitworth, & Greenfield, 1993; Huntsman, Lederer, & Peterman, 1984; Nuccio, Lingen, Burke, et al., 1996; Silver, 1986). These findings have also been used for preceptorship programs (Neverveld, 1990), symposia on nursing excellence (Ullery, 1984), and competency validation in maternal and child community health nursing (Patterson, Leff, Luce, et al., 2004).

The books FNE (Benner, 1984), Expertise in Clinical Nursing Practice (Benner, Tanner, & Chesla, 1996, 2009), and Clinical Wisdom and Interventions in Critical Care (Benner, Hooper-Kyriakidis, & Stannard, 1999, 2011) report studies of skill development in nursing and research-based interpretations of the nature of clinical nursing knowledge. The ongoing development of interpretive phenomenology as a narrative qualitative research method is described and illustrated in each of Benner’s knowledge development publications. The growing body of research that this work has generated is highlighted in the books Interpretive Phenomenology: Embodiment, Caring, and Ethics in Health and Illness (Benner, 1994b) and Interpretive Phenomenology in Health Care Research (Chan, Brykczynski, Malone, et al., 2010). Interpretive phenomenology is both a philosophy and a qualitative research methodology. In these books, Benner and colleagues delineate the historical background, philosophical foundations, and methodological processes of interpretive phenomenological research and examine caring practices and aspects of the moral dimensions of caring for and living with both health and illness.

Benner’s thesis (1984) that caring is central to human expertise, to curing, and to healing was extended in The Primacy of Caring: Stress and Coping in Health and Illness (Benner & Wrubel, 1989). The meaning of caring in this work is that persons, events, projects, and things matter to people. This work examines the relationships between caring, stress and coping, and health. It claims that caring is primary for the following reasons (Benner & Wrubel, 1989):

• What matters to people influences not only what counts as stressful but also what options are available for coping.

• It enables a person to notice salient aspects of a particular situation, to discern problems, and to recognize potential solutions.

This book articulates the nursing perspective of approaching persons in their lived experiences of stress and coping with health and illness. It is based on “the notion of the good inherent in the practice and the knowledge embedded in the expert practice of nursing” (Benner & Wrubel, 1989, p. xi). The primacy of caring has been used as a framework for nursing curricula in several schools of nursing including the University of Toronto in Ontario and McMurray College in Illinois (P. Benner, personal communication, January 12, 2000).

Benner’s work is research based and derived from actual practice situations. Darbyshire (1994) stated that her “work is among the most sustained, thoughtful, deliberative, challenging, empowering, influential, empirical [in true sense of being based on data) and research-based bodies of nursing scholarship that has been produced in the last 20 years” (p. 760). Benner’s work has been developed and applied in general staff nursing, critical care nursing, community health nursing, advanced practice nursing, and nursing education.

Benner’s research offers a radically different perspective from the cognitive rationalist quantitative paradigm prevalent during the 1970s and 1980s (Chinn, 1985; Webster, Jacox, & Baldwin, 1981). Her research constitutes an interpretive turn—a move away from epistemological, linear, analytical, and quantitative methods toward a new direction of ontological, hermeneutic, holistic, and qualitative approaches. Benner (1992) has stated that “the platonic quest to get to the general so that we can get beyond the vagaries of experience was a misguided turn….We can redeem the turn if we subject our theories to our unedited, concrete, moral experience and acknowledge that skillful ethical comportment calls us not to be beyond experience but tempered and taught by it” (p. 19).

Overview of Benner’s Philosophy

Nursing is a caring practice guided by the moral art and ethics of care and responsibility that unfolds in relationships between nurses and patients (Benner & Wrubel, 1989). The original domains and competencies of nursing practice (Benner, 1984) were identified and described inductively from clinical situation interviews and observations of novice and expert staff nurses in actual practice. This interpretive phenomenological study used a situational approach to the study of the knowledge and meanings embedded in the everyday practice of nurses. “The strength of this method lies in identifying competencies from actual practice situations rather than having experts generate competencies from models or hypothetical situations” (Benner, 1984, p. 44). A holistic perspective such as this provides details of the situational contexts that guide interpretation. Thirty-one interpretively defined competencies were identified and described from the narrative data. These competencies were grouped according to similarities of function, intent, and meaning to form seven domains of nursing practice (Box 7-1).

The helping role domain includes competencies related to establishing a healing relationship, providing comfort measures, and inviting active patient participation and control in care. Timing, readying patients for learning, motivating change, assisting with lifestyle alterations, and negotiating agreement ongoals are competencies in the teaching-coaching function domain. The diagnostic and patient-monitoring function domain refers to competencies in ongoing assessment and anticipation of outcomes. Competencies in the effective management of rapidly changing situations domain include the ability to contingently match demands with resources and to assess and manage care during crisis situations. The domain administering and monitoring therapeutic interventions and regimens incorporates competencies related to preventing complications during drug therapy, wound management, and hospitalization. Monitoring and ensuring the quality of health care practices domain includes competencies concerned with maintenance of safety, continuous quality improvement, collaboration and consultation with physicians, self-evaluation, and management of technology. The organizational and work-role competencies domain refers to competencies in priority setting, team building, coordinating, and providing for continuity of care.

The domains and competencies of nursing practice are nonlinear, with no precise beginning or endpoint. Instead, the nurse enters the hermeneutic circle of caring for the patient by way of whichever competency is needed at the time. One competency in one domain may be more prominent at a particular point in time, but all seven domains and numerous competencies (some not yet identified) will perhaps overlap and come into play at various times in the transitional (ongoing) process of caring for a patient.

The domains and competencies of nursing practice (Benner, 1984) were initially presented as an open-ended interpretive framework for enhancing understanding of the knowledge embedded in nursing practice. The expectation was that they be interpreted in the context of the situations from which they arise along with articulation of ideas of the good or ends of nursing practice. Narrative text must accompany the identification and description of domains and competencies. They are not mutually exclusive, jointly exhaustive categories that can be abstracted from their narrative sources. Because of the socially embedded, relational, and dialogical nature of clinical knowledge, the domains and competencies need to be adapted for each institution. This is achieved through study of clinical practice at each specific locale by systematically collecting 50 to 100 clinical narratives that are then interpreted to identify strengths, challenges, or silences in that practice community. A CPDM can then be designed specifically for the particular setting (Benner & Benner, 1999).

Benner’s work focuses on developing understanding of perceptual acuity, clinical judgment, skilled know-how, ethical comportment, and ongoing experiential learning. Benner’s proposal (1994b) that narrative data be interpreted as text rather than being coded with formal criteria is useful for understanding her work, specifically with regard to expertise, practical knowledge, and intuition. When these terms are considered as formal, explicit criteria (Cash, 1995; Edwards, 2001; English, 1993; Gobet & Chassy, 2008), erroneous interpretations of conservatism, traditionalism, or mysticism may arise. Therefore, each term is discussed in detail in the following sections.

The Dreyfus (Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1986) model of skill acquisition maintains that expert practice is holistic and situational. Qualitative distinctions betweenthe levels of competence, from the novice to expert skill acquisition model (Benner, et al., 1996), reflect “the situational and relational nature of common-sense understanding and developing expert practice” (Darbyshire, 1994, p. 757). According to this model, which Benner (1984) validated for nursing, expert practice develops over time through committed, involved transactions with persons in situations.

Clinical nursing expertise is embodied—that is, the body takes over the skill. Embodied expertise means that as human beings, we know things with our feelings and bodily senses (sight, sound, touch, smell, intuition), rather than just our rational minds. According to Brykczynski (1998):

To say that expertise is embodied is to say that, through experience, skilled performance is transformed from the halting, stepwise performance of the beginner—whose whole being is focused on and absorbed in the skilled practice at hand—to the smooth, intuitive performance of the expert. The expert performs so deftly and effortlessly that the rational mind, feelings, and perceptions are available to notice the patient and others in the situation and to perceive salient aspects of the situational context (p. 352).

Because expertise in this model is situational rather than defined as a trait or talent, one is not expert in all situations. When a novel situation arises or the usually expert nurse incorrectly grasps a situation, his or her performance in that particular situation relates more to competent or proficient levels. This experience then becomes part of the nurse’s repertoire of background experiences. In future encounters this nurse will approach a similar situation more expertly. This variable nature of expertise is very troublesome for those seeking abstract, objective, mutually exclusive, jointly exhaustive categories. However, it is quite compatible with the holistic, interpretive phenomenological approach. Experts functioning according to this perspective maintain a flexible and proactive stance with regard to possibly forming an incorrect grasp of the particular situation. For example, the intensive care unit (ICU) nurse described in FNE (Benner, 1984) who negotiated for more time for a patient to relax and stop resisting ventilator assistance before administration of additional sedation based her actions on the premise of a concern that she might be wrong. This model of expertise is open to possibilities in the particular situation, which fosters innovative interventions that maximize patient, staff, and other resources and supports to achieve an optimal outcome.

Next, an understanding of distinctions between practical and theoretical knowledge is essential for grasping this perspective (Kuhn, 1970; Polanyi, 1958). Embodied knowledge is the kind of global integration of knowledge that develops when theoretical concepts and practical know-how are refined through experience in actual situations (Benner, 1984). The more tacit knowledge of experienced clinicians is uniquely human. It is the kind of knowledge that computers do not have (Dreyfus, 1992). It requires a living person, actively involved in a situation with the complexity of background and context. The following distinction between human and computer capabilities clarifies aspects of the theory-practice gap so widely discussed in practice disciplines:

All of knowledge is not necessarily explicit. We have embodied ways of knowing that show up in our skills, our perceptions, our sensory knowledge, our ways of organizing the perceptual field. These bodily perceptual skills, instead of being primitive and lower on the hierarchy, are essential to expert human problem-solving which relies on recognition of the whole (Benner, 1985b, p. 2).

Theoretical knowledge may be acquired as an abstraction through reading, observing, or discussing, whereas the development of practical knowledge requires experience in an actual situation because it is contextual and transactional. Clinical nursing requires both types of knowledge. Table 7-1 provides definitions and examples of aspects of practical knowledge based on Benner (1984).

TABLE 7-1

Aspects of Practical Knowledge

| Aspect | Definition | Examples |

| Qualitative distinctions | Perceptual, recognitional clinical judgment that refers to accurate detection of subtle alterations that cannot be quantified and that are often context dependent | Discrete alterations in skin color Significance of changes in mood Different manifestations of anxiety |

| Maxims | Cryptic statements that guide action and require deep situational understanding to make sense | When you hear hoofbeats in Kansas, think horses, not zebras. Follow the body’s lead. |

| Assumptions, expectations, and sets | Knowledge from past experience that helps orient and provide a frame of reference for anticipatory guidance along the typical trajectory Assumptions are beliefs that something is true; expectations are outcomes that can be reasonably anticipated following a certain scenario; sets are inclinations or tendencies to respond to anticipated situations |

Assumptions include the ability to maintain and communicate hope in situations based on possibilities learned from previous similar situations. It is expected that an obese person with essential hypertension who loses weight and engages in aerobic exercise 3 times a week will experience a decrease in blood pressure. A set can be illustrated by thinking about the difference in the way a nurse would approach a woman in labor for whom everything seemed to be going normally and the way a nurse would approach the woman if there was a known fetal demise. |

| Common meanings | Shared, taken for granted, background knowledge of a cultural group that is transmitted in implicit ways | It is often better to know even bad news than not to know. The need to advocate for the vulnerable and voiceless |

| Paradigm cases | Clinical experiences that stand out in one’s memory as having made a significant impact on the nurse’s future practice and profoundly alter perceptions and future understanding | The first patient a nurse worked with who stops smoking The first patient with a breast lump who a nurse refers for evaluation |

| Exemplars | Robust clinical examples that convey more than one intent, meaning, or outcome and can be readily translated to other clinical situations that may be quite different An exemplar might constitute a paradigm case for a nurse depending on its impact on personal knowledge and future practice |

Helping a patient/family to experience a peaceful death Teaching/coaching a patient/family to live with a chronic illness |

| Unplanned practices | Knowledge that develops as the practice of nursing expands into new areas | Experience gained with available alternative therapies and patient responses to them |

Developed from Benner, P. (1984). From novice to expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley.

The examples of aspects of practical knowledge described in Table 7-1 are self-explanatory. However, maxims require explanation. The maxim “When you hear hoofbeats in Kansas, think horses, not zebras” reminds clinicians that for most common conditions time-consuming, extensive searches for rare conditions are usually not warranted. The maxim “Follow the body’s lead” relates to the perceptual acuity developed by nurses to intuitively sense the meaning of a patient’s bodily responses. It appears, for example, in situations in which patients are being assessed for readiness to be weaned from ventilator assistance and when nurses evaluate comfortable positions preferred by a particular infant.

In the interpretive phenomenological perspective, the body is indispensable for intelligent behavior rather than interfering with thinking and reasoning. According to Dreyfus (1992), the following three areas underlie all intelligent behavior:

1. The role of the body in organizing and unifying our experience of objects

2. The role of the situation in providing a background against which behavior can be orderly without being rule-like

3. The role of human purposes and needs in organizing the situation so that objects are recognized as relevant and accessible

Finally, intuition, rather than mystical, is defined as immediate situation recognition (Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1986). This definition is based on Merleau-Ponty’s (1962) ideas that “the body allows for attunement, fuzzy recognition of problems, and for moving in skillful, agentic, embodied ways” (Benner, 1995, p. 31). Intuition functions on a background understanding of prior similar and dissimilar situations and depends on the performer’s capacity to be confident in and trust his or her perceptual awareness. This ability is similar to the ability to recognize family resemblances in faces of relatives whose objective features may be quite different. Benner (1996) argues that “[c]linical reasoning is necessarily reasoning in transition, and the intuitive powers of understanding and recognition only set up the condition of possibility for confirmatory testing or a rapid response to a rapidly changing clinical situation” (p. 673).

Interfacing with Practice

Practice and theory are seen as interrelated and interdependent. An ongoing dialogue between practice and theory creates new possibilities (Benner & Wrubel, 1989). In Benner’s work, practice is viewed as a way of knowing in its own right(Benner, 1999). As noted earlier, Benner’s approach to articulating nursing practice is inductive, developmental, and interpretive. She locates it in “the feminist tradition of consciousness raising that seeks to name silences and to bring into public discourse poorly articulated areas of knowledge, skill, and self-interpretations in clinical nursing practice” (Benner, 1996, p. 670).

Articulation is defined as “describing, illustrating, and giving language to taken-for-granted areas of practical wisdom, skilled know-how, and notions of good practice” (Benner, Hooper-Kyriakidis, & Stannard, 1999, p. 5). Since the publication of FNE in 1984, which involved staff nurses from various clinical areas, Benner and colleagues have focused on articulating skill acquisition processes and competencies of nurses in acute and critical care areas (Benner, et al., 1996, 2009; Benner, et al., 1999, 2011). Domains and competencies have also been useful for articulation of knowledge embedded in advanced nursing practice (Brykczynski, 1999; Fenton, 1985; Fenton & Brykczynski, 1993; Lindeke, Canedy, & Kay, 1997; Martin, 1996).

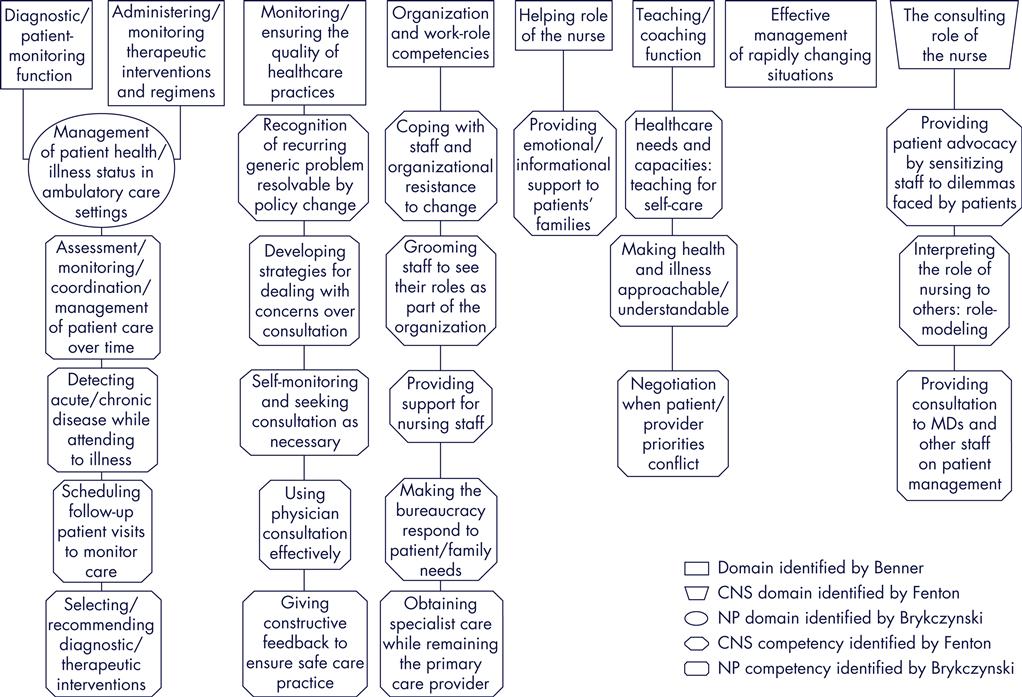

Selected studies illustrate applications of Benner’s work and continued articulation of the competencies of advanced nursing practice. Fenton’s (1985) study indicated that the original domains were present in the practice of clinical nurse specialists (CNSs). She identified additional competencies for three of Benner’s original domains and described one additional domain, the consulting role of the nurse (Figure 7-1). Fenton described the competency making the bureaucracy respond in her study of CNSs. This involved knowing how and when to work around bureaucratic roadblocks in the system so patients and families could receive needed care.

Brykczynski (1985) developed an additional domain from her study of outpatient nurse practitioner (NP) practice. The new domain consolidated two of Benner’s domains that were typical of inpatient nursing practice—diagnostic and patient monitoring function and administering and monitoring therapeutic interventions and regimens (see Figure 7-1)—and replaced it with management of patient health/illness status in ambulatory care settings. The remaining five of Benner’s seven domains were interpreted as valid for the practice of the NPs studied. The cumulative nature of qualitative research is demonstrated by Brykczynski’s (1985) identification of managing the system as a competency in her NP study. Further interpretation revealed that this competency was identical to making the bureaucracy respond described by Fenton with CNSs. This competency involves negotiating and interpreting policies and procedures for patients so that they can fit into the system and get what they need. It demands flexibility in the nurse’s stance toward the system and requires not getting caught up in unproductive interpersonal conflicts; instead, the nurse uses knowledge of the bureaucracy and interpersonal communication skills to provide care for patient needs.

Later Fenton and Brykczynski compared the findings of their studies to discover commonalties and distinctions between the practice of NPs and CNSs. The comparative analysis indicated “a shared core of advanced practice competencies as well as distinct differences between the practice roles” (Fenton & Brykczynski, 1993, p. 313). As noted, making the bureaucracy respond was shared by both groups; however, the organizational and work-role competencies were more prominent inthe practice of the CNSs. NPs practiced more as direct providers of care, whereas CNSs functioned more as facilitators of care. The new domain, the consulting role of the nurse, was evidenced in the practice of both CNSs and NPs. Competencies in this domain represent the initial articulation of skills and knowledge specific for advanced nursing practice.

Lindeke, Canedy, and Kay (1997) followed this work with a study of similarities and differences between CNS and NP roles among CNSs who completed a post-master’s NP program. They found that although practice domains were similar, there was distinct expression of the domains in each advanced practice nurse (APN) role. The post-master’s participants stated that they “experienced significant role change in the transition from CNS to NP roles” (Lindeke, et al., 1997, p. 287); important advanced practice role findings for curriculum planning.

Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice with Benner’s Approach

Benner addresses critical thinking in a developmental and interpretive way. Whereas formal definitions of critical thinking tend to signify abstract, rational calculation with analysis and weighing of options to arrive at decisions, Benner specifies that a thinking process for beginning nurses and an interpretive process based on past-whole-concrete cases with expert nurses. Benner’s perspective is inclusive in that it incorporates the formal, analytical definition at novice and advanced beginner levels of practice and the more integrative, qualitative definition at proficient and expert practice levels.

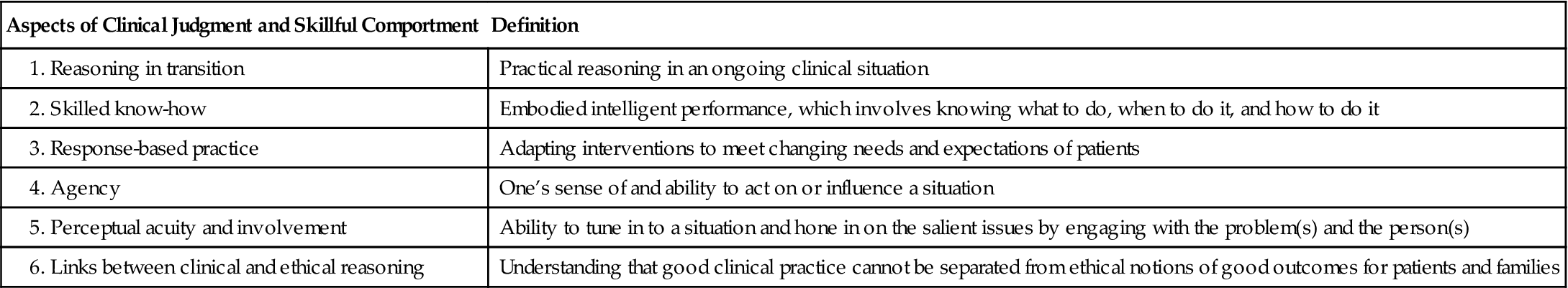

Benner and colleagues (1999) identified six aspects of clinical judgment and skillful comportment that can be viewed as interpretive aspects of critical thinking (Table 7-2). These six aspects were identified and described through study of critical care nursing practice. They constitute components of the thinking-in-actionapproach required in acute and critical care. (1) Reasoning in transition involves the thinking-in-action demanded as an ongoing situation evolves over time. (2) Skilled know-how refers to embodied knowing described earlier. (3) Response-based practice involves the ability to read a situation and respond flexibly and proactively to changing needs and demands. (4) Agency is the nurse’s ability to function within a given situation. (5) Perceptual acuity and involvement refer to acquiring a good grasp of the situation through emotional engagement with the problem and interpersonal involvement with patients and families. “Notions of good guide the actions of nurses and help them notice clinical and ethical threats to patients’ well-being” (Benner, et al., 1999, p. 17), thus (6) linking clinical and ethical reasoning.

TABLE 7-2

Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice with Benner’s Philosophy

Developed from Benner, P., Hooper-Kyriakidis, P., & Stannard, D. (1999). Clinical wisdom and interventions in critical care: A thinking-in-action approach. Philadelphia: Saunders.

In this work Benner and colleagues (1999) sought to generate “a dialogue with practice and theory to create an enlarged view of rationality that is dialogic, relational, and cumulative rather than a collection of decisions and facts” (p. 22). The second edition of this work (Benner, et al., 2011) presents educational strategies to address practice. According to Benner and colleagues (1999), “[c]linical reasoning requires reasoning-in-transition (or reasoning about the changes in a situation) about particular patients and families” (p. 10). The term thinking-in-action is intended to convey “the innovative and productive nature of the clinician’s active thinking in ongoing situations” (Benner, et al., 1999, p. 5). According to Benner and Benner (1999):

Clinical practice is a socially embedded knowledge that draws on theoretical and scientific empirical knowledge but also on the practical know how, compassionate meeting of the other, and front-line knowledge work of practitioners…. The practitioner, whether nurse, physician, lawyer, teacher, or social worker, reasons about the particular across time, observing transitions in the client’s condition, and also transitions in his or her own understanding of the clinical situation (p. 22).

Benner has suggested that both practical clinical knowledge and caring practices have been minimized in modern health care. It is her hope that identification and description of these practices on which health care institutions depend will promote their recognition and legitimacy (Benner, 1994a). These aspects of practice have particular relevance to minimizing errors and promoting safety in health care situations (Benner, Malloch, & Sheets, 2010).

In Benner’s work nursing practice is an interpretive (hermeneutic) of the patient situation. She agrees with Good and Good (1981) that “all clinical encounters have a hermeneutic dimension; clinicians and patients interpret one another’s meanings to bring to light an underlying coherence or sense” (p. 208). She maintains as do Good and Good (1981) that “the negotiation by the healer and the patient of a common understanding of the cause of suffering, the construction of a shared illness reality, provides the basis for the therapeutic efficacy of many healing transactions” (p. 193). For Benner, nursing practice is constituted by a circular hermeneutic process between the nurse, the patient, and the ongoing situational context.

Nursing Care of Debbie with Benner’s Approach

This case is presented in a factual outside-in way that Foucault (1963) called the clinical gaze—that is, we observe but do not meet Debbie. Presumably, the nurse would meet Debbie and discover her concerns to develop a shared understanding of how to proceed. The clinical hermeneutic takes place as the nurse interprets nursing care.

Domain: The Helping Role

The helping role domain is a good place to start in thinking about Debbie’s care. In establishing a healing relationship with Debbie, you would begin by getting to know her as a person. By learning Debbie’s unique life situation, beliefs, values,needs, and goals, you develop an understanding of the meanings this illness experience has for her. At the same time, who the nurse is, what the nurse’s background experiences have been, and what the nurse’s level of competence is in caring for women with cancer influence how the particular nurse-patient transaction develops over time. Debbie’s relationships with each of the nurses involved in her care will vary in some ways according to each nurse’s competence, unique personality, and approach to care.

Benner and colleagues (1996) describe the experiential learning associated with learning the skill of involvement. Learning how to be engaged in the clinical situation and how to be connected with patients and families in helpful ways is ongoing. This skill requires attunement to the situation and to the individuals involved because what is an appropriate level of involvement at one phase may be inappropriate at another. Also, different individuals have different comfort zones and expectations, and these may change during the course of an illness. By engaging in ongoing dialogue about the situated meanings of Debbie’s illness experience, you can personalize her care and help Debbie discover her own situated possibilities. Debbie and you can plan her care together and modify it according to transitions as the situation evolves.

Other salient issues might emerge in the helping relationship, including maximizing Debbie’s participation and control in her recovery, interpreting kinds of pain, and selecting appropriate strategies for pain management and control. Guiding Debbie through the emotional, physiological, social, and developmental changes of losing her uterus and ovaries at 29 years of age is also important here. No general techniques can be offered because treatment depends on identification of Debbie’s concerns and her openness and readiness to discuss them. The patient-nurse relationship uncovers situated possibilities. For example, Debbie may be fearful that she might die, but such fears are best discussed when she indicates that she is ready. You can follow Debbie’s lead by asking well-timed questions. To do this, however, you must address your own fears of dying to be open to Debbie’s.

Domain: The Teaching-Coaching Function

Teaching-coaching functions may be relevant in Debbie’s situation depending on your assessment of her readiness to learn. For example, her tears might signal a readiness to engage in discussion of her fears, or they may indicate sadness and depression. Understanding the meaning of Debbie’s tears requires attentive listening and open-ended questioning to make the necessary qualitative distinctions. If Debbie appears to be receptive to learning, coaching her about the implications of her illness and recovery in her unique life situation can proceed in an individualized way.

Domain: The Diagnostic and Monitoring Function

During all points of Debbie’s care, you will anticipate future problems and attempt to understand the particular demands of Debbie’s illness. For example, you will anticipate care needs related to Debbie’s catheterizing herself at home, managing her pain, and controlling her nausea. Based on your and Debbie’s assessments ofher potential for wellness and responses to various treatment strategies, you will develop a discharge plan and discuss this plan with the home-care nurse.

Domain: Organizational and Work-Role Competencies

Building and maintaining a therapeutic team to provide optimum therapy for Debbie is a relevant competency from this domain. No information is available on the staffing situation in Debbie’s nursing unit, so the significance of the other competencies in this domain is unknown. However, communicating Debbie’s concerns will be crucial.

Nursing Care of Rosa with Benner’s Approach

Domain: The Helping Role

The holistic interpretive perspective of the nurses enabled them to perceive Rosa’s situation very differently from the objective clinical gaze of the physicians (Foucault, 1963). As one of the nurses narrates:

Neuro came in and looked at her head—that was what they saw, her head and lack of neurological function. GI came in and they saw just the liver. Renal came in and saw her kidneys. OB came in and saw a comatose postpartum woman. Anesthesia came in and so on (Brykczynski, 1998, pp. 355-356).

This excerpt illustrates that the objective clinical gaze is depersonalizing and divides the person into the separate organs and systems of interest to different specialties.

The nurses were aware that Rosa was a young, healthy woman before developing this rare pregnancy-induced illness, and they had developed the clinical perceptual acuity to follow the lead of Rosa’s body toward restoration of health. In understanding how the nurses established a healing climate for Rosa, it is important to know that no mother had ever been declared a “do not resuscitate” (DNR) in this labor and delivery (L&D) unit before. Having no experience with such a situation, the nurses did what was necessary to maintain and support Rosa so that her body could heal itself—if that was to be. This is an example of the common meaning Benner (1984) calls situated possibility, in which nurses learn that even the most deprived illness circumstance has its own possibility. Knowing that the hormonal stress response associated with abandoning hope can influence the course of an illness (Benner, 1985a), both the nurses and the family members remained hopeful. They stayed nearby and prayed for Rosa throughout her hospital stay. The power of prayer in influencing healing is recently receiving more research attention as spirituality is becoming more widely recognized (Byrd, 1997).

The following two obvious aspects clearly affected the development of a collaborative relationship between Rosa and her nurses:

1. Rosa was comatose and unable to communicate in any obvious way with the nurses caring for her.

2. The majority of the nurses spoke only English and knew few, if any, words in Spanish.

In striving to create a healing climate for Rosa, the nurses realized that she probably could hear but was unable to acknowledge this. For this reason, they spoke to her while they provided her care. If an interpreter was not available, they spoke to her in English, hoping to convey their feelings and concern by the tone of their voices. The nurses reported that when Rosa returned to the conscious state, she recognized those who had cared for her by their voices.

Domain: The Teaching-Coaching Function

The nurses reported that they described what they were doing while they cared for Rosa and consistently provided ongoing feedback about her condition and her family to promote her participation in care as much as possible. They were involved with the father of the baby, who was struggling with this very difficult situation. The nurse reported:

At times he would cry if he was holding the baby and not want to cry—especially being a Hispanic male. This was not something he wanted to do and tried not to. We encouraged him to hold the baby himself. We realized that this was not something he had planned on—you know basically the woman is expected to help with the baby and integrate the baby into the household. It was kind of like, “here’s the baby,” and it was really hard for him. He had a lot of mixed emotions. He wasn’t sure what he was going to do (Brykczynski, 1993-1995).

In coaching the father through this uncharted illness experience, the nurses received much support from a social worker who was fluent in Spanish.

Domain: The Diagnostic and Monitoring Function

Understanding the particular demands and experiences of Rosa’s illness was crucial in anticipating her care needs. The nurses reported reading everything they could find about Rosa’s rare condition (acute fatty liver of pregnancy) to increase their understanding of her illness and enhance their ability to assess her potential for wellness and for responding to various treatment strategies.

Domain: Administering and Monitoring Therapeutic Interventions and Regimens

All the competencies in this domain were significant in this situation. In an effort to normalize the situation as much as possible—for the nurses as well as Rosa—they continued to bring Rosa’s baby in to her and place the baby on her chest. One of the critical care nurses participating in the interviews recalled a postpartum woman in ICU for whom the nurses played a tape of her baby’s sounds during her stay in the ICU. Rosa was fortunate that she was not transferred to the ICU but instead received care from obstetrics (OB) nurses who recently received critical care training. One nurse describes how bringing the baby to the mother helped them as well as Rosa:

Part of it I think initially when we were bringing the baby in was it helped us in a way too because we didn’t want the baby staying in the nursery for 4 or 5 days without really being nurtured (Brykczynski, 1993-1995).

The nurses developed the idea of providing nutritional support for Rosa. They reported approaching every specialty physician team involved in Rosa’s care, including OB, neurology, renal, and gastrointestinal (GI), until one specialty service agreed to order a nutritional consult so that Rosa could receive tube feedings. Based on their assessment of the physiological parameters and experience with patients with this rare condition who did not do well, the physicians’ prognosis for Rosa was bleak. Their attitude toward the nurses was one of humoring them. They reasoned that “if it makes the nurses feel better, they can feed her,” because they felt it would not do her any harm. As it turned out, nutritional support was essential to her recovery, particularly for her liver regeneration.

Domain: Organizational and Work-Role Competencies

Building and maintaining a therapeutic team to provide optimum therapy was an important competency in this situation. As noted, the group of eight OB nurses who had recently participated in critical care training experiences, which prepared them to care for high-risk women during labor and delivery, formed the team of nurses who cared for Rosa. Their obstetric nursing background and recent critical care experience made them uniquely capable of individualizing Rosa’s care. By expanding into a new area of nursing practice, the nurses established the opportunity to develop new knowledge in high-risk OB nursing. For example, as OB nurses they were acutely aware that not hearing the sounds of her baby could make Rosa feel that her baby was not alive. An interesting aspect of this situation was that, as OB nurses, nutrition was not generally a particularly salient issue for them. One nurse related:

It’s real common for us not to feed our patients. When they are on mag [magnesium sulfate] they may go for three days without food. Or even postpartum for PIH [pregnancy-induced hypertension], so we’re used to starving our patients because it really is in the back of our minds that it is okay not to feed a patient because they are usually normal, healthy people who are pregnant. [The idea of feeding her] developed from our experiences rotating through the critical care units where we came in contact with TPN (total parenteral nutrition) and hepatic A tube feedings and that made us more aware of nutrition as a support for this patient (Brykczynski, 1998, p. 356).

Domain: Monitoring and Ensuring the Quality of Health Care Practices

The group of specially trained OB nurses had ready access to the critical care nurses, with whom they had recently worked, thereby providing readily accessible backup for safe care. This combination of obstetric and critical care knowledge and skill enabled them to ensure that optimal supportive care was provided. They made adjustments to the care plan far beyond those recommended by the physicians. Examples included bringing the baby to the mother and providing nutritional support.

One of the two nurses who described this exemplar in Brykczynski’s (1998) study reported caring for Rosa as she regained consciousness. This nurse related that she was performing the standard neurological check and noticed a slightchange in Rosa’s pupil reaction, which was nonexistent before. She rechecked the pupils and had another nurse verify that there was a slight response. The physician who was summoned did not detect any pupillary reaction. Gradually, however, Rosa became more and more alert throughout this nurse’s shift and was able to be extubated. Rosa’s baby was crying in the room when Rosa regained consciousness. Remarkably, Rosa’s liver had regenerated; she recovered with no residual brain damage; and she was discharged home to be with her baby and the baby’s father. This case history constitutes an exemplar of nursing provided in an open, receptive, adaptive, creative, and hermeneutic manner as described by Benner and colleagues as a reasoning-in-transition approach (Benner, et al., 1999). For teaching students this case can be presented as an unfolding case study to help students learn how clinical reasoning changes over time (Benner, Sutphen, Leonard, et al., 2010).