Levine’s Conservation Model in Nursing Practice

Karen Moore Schaefer∗

Nursing is a profession as well as an academic discipline, always practiced and studied in concert with all of the disciplines that together form the health sciences…. Scientific knowledge from many contributing disciplines is, in fact, connected to nursing, as an adjunct to the knowledge that nursing claims for its own.

History and Background

The conservation model was originally an organizing framework for teaching undergraduate nursing students (Levine, 1973a). Levine’s book Introduction to Clinical Nursing (1973a) addressed the “whys” of nursing actions. Levine taught the skill of nursing and the rationale for the actions. She demonstrated high regard for the contribution of the adjunctive sciences to a theoretical basis of nursing in a clear voice for discipline development and attention to the rhetoric of nursing theory (Levine, 1988, 1989b,c, 1994, 1995).

The universality of the conservation model is supported by its use with a variety of patients of varied ages in a wide range of settings, including critical care (Langer, 1990; Litrell & Schumann, 1989; Lynn-McHale & Smith, 1991; Taylor, 1989; Tribotti, 1990), acute care (Foreman, 1991; Molchany, 1992; Roberts, Brittin, Cook, et al., 1994; Roberts, Brittin, & deClifford, 1995; Schaefer, 1991; Schaefer, Swavely, Rothenberger, et al., 1996), and long-term care (Burd, Olson, Langemo, et al., 1994; Clark, Fraaza, Schroeder, et al., 1995; Cox, 1991). It is also used with neonates (Tribotti, 1990), infants (Deiriggi & Miles, 1995; Mefford, 1999, 2004; Mefford & Alligood, 2011a,b; Newport, 1984), young children (Dever, 1991; Savage & Culbert, 1989), pregnant women (Oberg, 1988; Roberts, Fleming, & Yeates-Giese, 1991),young adults (Pasco & Halupa, 1991), women with chronic illness (Schaefer, 1996), long-term ventilator patients (Delmore, 2003), and the elderly (Cox, 1991; Foreman, 1991; Happ, Williams, Strumpf, et al., 1996). It has been successfully used in communities (Dow & Mest, 1997; Pond, 1991), emergency departments (Pond & Taney, 1991), extended care facilities (Cox, 1991; R. Cox, personal communication, February 21, 1995), critical care units (Molchany, 1992), primary care clinics (Schaefer & Pond, 1994), and operating rooms (Crawford-Gamble, 1986; Piccoli & Galvao, 2001) as well as for wound care and enterostomal therapy (Cooper, 1990; Leach, 2006; Neswick, 1997), care of intravenous sites (Dibble, Bostrom-Ezrati, & Ruzzuto, 1991), management of patients on long-term ventilation (Higgins, 1998), and care of patients undergoing treatment for cancer (Mock, St. Ours, Hall, et al., 2007; O’Laughlin, 1986; Webb, 1993).

The model is used for quantitative and qualitative research addressing practice issues. Melacon and Miller (2005) found massage therapy effective as complementary support for patients, reducing their low back pain intensity and preventing further decline. Mock, Pickett, Ropka, and colleagues (2001) used the model to study the effect of exercise on fatigue in patients with cancer. Coyne and Rosenzweig (2006) studied fatigue and functional status in women with cancer metastasis, using the model to assess energy and structural, personal, and social integrity. Hanna, Avila, Meteer, and colleagues (2008) found that comprehensive exercise for patients with cancer results in significant improvements in functional status, fatigue, and mood in treatment and recovery. Zalon (2004) found that pain, depression and fatigue, and return of functional status in older adults after major abdominal surgery were significantly related to patient perception of functional status and recovery.

Chang (2007) studied swaddling guided by Levine’s model and found swaddling conserved energy because the heart rates of swaddled infants increased less than those of the control group. Watanabe and Nojima (2005) proposed a middle-range theory describing the “calm delivery” and conservation of social integrity relationship based on key indicators of parental relationships, person-environment relationship, family function, dyadic relationship between parents, and dyadic relationship between the generations. Gregory (2008) found premature infants who did not receive fortified enteral breast milk feedings developed necrotizing enterocolitis when respiratory support was increased to maintain oxygenation. Mefford (2004; Mefford & Alligood, 2011a) developed and tested a theory of health promotion for preterm infants.

Ballard, Robley, Barrett, and colleagues (2006) applied the conservation model for a phenomenological study of patients’ recollections of therapeutic paralysis in intensive care. They found that patients reconstruct their lives in concert with care given by nurses who modified physiological stress to reduce chances of mortality and maintain wholeness. Delmore (2006) studied fatigue and protein calorie malnutrition in adult long-term ventilated patients during the weaning process, and found patients experienced moderate to severe fatigue during weaning and prealbumin levels affected the level of fatigue experienced. Jost (2000) studied staff nurse productivity, burnout, and satisfaction issues.

Overview of Levine’s Conservation Model

According to Levine (1973a), “Nursing is human interaction” (p. 1). “The nurse enters into a partnership of human experience where sharing moments in time—some trivial, some dramatic—leaves its mark forever on each patient” (Levine, 1977, p. 845). As a human science, the profession of nursing integrates the adjunctive sciences (e.g., chemistry, biology, anatomy and physiology, psychology, sociology, anthropology, philosophy, medicine) to develop the practice of nursing.

Three major concepts form the basis of the model and its assumptions: (1) conservation, (2) adaptation, and (3) wholeness. Conservation is a natural law fundamental to many sciences. Levine (1973a) explains that individuals continuously defend their wholeness.

Conservation is the keeping together of the life system. To keep together means to maintain a proper balance between active nursing interventions and patient participation, in which the patient participates within the safe limits of his or her ability. Individuals defend that system in constant interaction with their environments and choose the most economical, frugal, energy-sparing options available to safeguard their integrity. Energy sources cannot be directly observed but the consequences (clinical manifestations) of their exchange are predictable, manageable, and recognizable (Levine, 1991). Conservation is about achieving balance between energy supply and demand within the unique biological realities of the individual.

Adaptation is an ongoing process of change in which individuals retain their integrity within the realities of their environments (Levine, 1989a). Change is the life process, and adaptation is the method of change. The achievement of adaptation is “the frugal, economic, contained, and controlled use of environmental resources by the individual in his or her best interest” (Levine, 1991, p. 5). Individuals possess a range of adaptive responses unique to them. The ranges vary with ages and are challenged by illness. For example, the hypoxic drive stimulates breathing in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. History, specificity, and redundancy characterize adaptations that await the challenges to which they respond (Levine, 1995). The severity of responses and the adaptive patterns vary based on specific genetic structures and influences of social, cultural, spiritual, and experiential factors.

Redundancy represents the fail-safe anatomical, physiological, and psychological options available to individuals to ensure continued adaptation (Levine, 1991). Levine (1991) proposed that “[a]chieving health is predicated on the deliberate selection of redundant options” (p. 6). Survival depends on redundant options that are challenged and limit illness, disease, and aging.

Wholeness exists when interactions with and adaptations to the environment permit assurance of integrity (Levine, 1991). Nurses use of the conservation principles to promote wholeness. Recognition of an open, fluid, constantly changing interaction between the individual and the environment is basic to holistic thought. Wholeness is health; health is integrity. Health is the pattern, and well-being is the goal of adaptive change.

Levine (1988) referred to the metaparadigm concepts of person, environment, health, and nursing as commonplaces of the discipline because they are necessaryfor any description of nursing. Persons are holistic beings who are sentient, thinking, future-oriented, and aware of their past. Wholeness (integrity) of individuals demands that “isolated aspects…have meaning outside of the context within which the individual experiences his or her life” (Levine, 1973a, pp. 325, 326). Persons are in constant interaction with the environment, responding to change in an orderly, sequential pattern, adapting to forces that shape and reshape their essence. According to Levine (1973a), the person can be defined as an individual, a group (family), or a community of groups and individuals (Pond, 1991).

The environment completes the wholeness of the person. Each individual has his or her own internal and external environments. The internal environment includes physiological and pathophysiological aspects of the patient that are challenged by changes in the external environment. External environmental factors impinge on and challenge the individual. Acknowledging the complexity of environment, Levine (1973a) adopted three levels of environment identified by Bates (1967): (1) perceptual, (2) operational, and (3) conceptual. Perceptual environment includes aspects of the world that individuals intercept or interpret through the senses. Operational environment includes elements that physically affect individuals but are not directly perceived (e.g., radiation, microorganisms). Conceptual environment includes cultural patterns that affect behavior characterized by spiritual existence and mediated by symbols of language, thought, and history (e.g., values, beliefs).

Health and disease are patterns of adaptive change with the goal of well-being (Levine, 1971b). Health is socially defined by the following question (Levine, 1984): “Do I continue to function in a reasonably normal fashion?” Health (wholeness) is the goal of nursing and implies the unity and integrity of the individual. Illness is adaptation to noxious environmental forces. Levine (1971a) proposes that “[d]isease represents the individual’s effort to protect self-integrity, such as the inflammatory system’s response to injury” (p. 257). Disease is unregulated and undisciplined change that must be stopped to prevent death (Levine, 1973a).

Nursing involves engaging in “human interaction” (Levine, 1973a, p. 1). Individuals seek nursing care when they are no longer able to adapt. The goal of nursing is to promote adaptation and maintain wholeness. This goal is accomplished through the conservation of energy and structural, personal, and social integrity.

Energy conservation depends on free exchange with environment so living systems can constantly replenish their supply (Levine, 1991). Conservation of energy is integral to individual ranges of adaptive responses. Conservation of structural integrity depends on the defense system that supports repair and healing in response to challenges from internal and external environments. Conservation of personal integrity recognizes individual wholeness in response to environment as the individual strives for recognition, respect, self-awareness, humanness, holiness, independence, freedom, selfhood, and self-determination.

Conservation of social integrity recognizes individual functioning in a society that helps establish the boundaries of the self. Social integrity is created with family and friends, workplace and school, religion, personal choices, and cultural and ethnic heritage (Levine, 1996). With political and economic control, the health care system is part of the social system of individuals. Levine (1991) contends that“[c]onservation of integrity is essential to assuring wholeness and providing the strength needed to confront illness and disability” (p. 3).

Levine (1973a) stresses that patient understanding of plans of care and diagnostic studies is vital. To this understanding the nurse contributes knowledge of nursing science, a careful history of the patient’s illness, the patient’s perception of the current predicament, information gained from family and friends, and acute observation of the patient and his or her interactions with others (Levine, 1966a). This integrated approach to patient-centered care provides the basis for collaborative care and the establishment of partnerships in the delivery of comprehensive care. Treatment focuses on the management of the organismic responses, including the following:

1. Flight/fight response is the most primitive.

2. Inflammatory/immune system response provides structural continuity and promotes healing.

3. Stress response develops over time as experiences accumulate, leading to system damage if prolonged.

4. Perceptual awareness response observes the environment and converts observations to meaningful experience.

These four responses work together to protect the individual’s integrity as essential components of the individual’s whole response.

The goal of patient care is promotion of adaptation and well-being. Because adaptation is predicated on redundant options and rooted in history and specificity, therapeutic interventions vary depending on the unique nature of each person’s response.

Theories for Practice from the Model

The model provides a basis for the following four theories for practice (Mefford, 2004):

2. The Theory of Therapeutic Intention

4. The Theory of Health Promotion for Preterm Infants (Mefford, 2000)

The Theory of Conservation, rooted in the universal principle of conservation, is foundational for the model (Alligood, 1997, 2006, 2010). The purpose of conservation is to “keep together.” According to Levine (1973a), “To keep together means to maintain a proper balance between active nursing interventions coupled with patient participation on the one hand and the safe limits of the patient’s abilities to participate on the other” (p. 13). The patient interacts with the environment in a singular but integrated fashion. The person represents a system that is more than the sum of its parts and reacts as a whole being. As part of the patient’s environment the nurse supports patient responses. All nursing acts of conservation are devoted to restoring symmetry of response with the goal of maintaining wholeness (Levine, 1969).

In developing the Theory of Therapeutic Intention, Fawcett (2005) cites Levine’s model for its capacity to organize nursing interventions using biologicalrealities that nurses confront and proposed therapeutic regimens to support the following goals (Fawcett, 2000):

• Facilitate integrated healing and optimal restoration of structure and function.

• Provide support for a failing autoregulatory portion of the integrated system.

• Restore individual integrity and well-being (Gagner-Tjellesen, Yurkovich, & Gragert, 2001).

• Provide supportive measures to ensure comfort and promote human concern.

• Balance a toxic risk against the threat of disease (Piccoli & Galvao, 2001).

• Manipulate diet and activity to correct metabolic imbalances and stimulate physiology.

• Reinforce or antagonize usual response to create therapeutic change.

Levine’s Theory of Redundancy, grounded in adaptation, has the capacity to expand our understanding of aging (Fawcett, 2005). Redundancy is predicated on the ability of a human to “monitor its own behavior by conserving the use of resources required to define its unique identity” (Levine, 1991, p. 4). Inherent in the ability to select from the environment is availability of options from which choices are made.

Mefford (2000; Mefford & Alligood, 2011a,b) tested the validity of her Middle Range Theory of Health Promotion for Preterm Infants and found that consistency of nurse caregivers mediated the infant’s integrity at birth and the age that health was obtained, and an inverse relationship between the use of resources by preterm infants during their initial hospital stay and consistency of caregivers. Watanabe and Nojima (2005) developed a middle-range theory with substruction using Levine’s Conservation Model to describe, “calm delivery.” Literature review identified 22 concepts related to the four integrities of the model. Conservation of social integrity was the integrity related to a cluster of five concepts, including social support; dyadic relationships between parents, generations, and environment; and family function. They identified significant cues for researchers to conduct studies in this area.

Anecdotal reports are supportive of the theories in practice. For example, a patient with diabetes who follows a diet and exercise program is more likely to control his or her blood sugar levels (therapeutic intention) than one who does not follow the same program. Patients with emphysema who space activities to conserve energy will be more satisfied with daily life than patients who do not space activities (conservation). Patients with chronic illness manage their lives better when given options for treatment than patients who are not provided with options (redundancy). According to Levine (1991), failure of redundant options (loss of hearing in one ear) helps explain aging. The Theory of Redundancy might explain the process of aging because as one ages organ function declines, in some cases as a part of the aging process. If a kidney fails, the Theory of Redundancy no longer is valid because only one kidney remains. This is also true if a patient can only hear from one ear; the option to hear with both ears no longer exists. Of course, a hearing aid may help restore hearing in the ear with less than optimal function, supporting the Theory of Redundancy through the use of technology.

Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice with Levine’s Model

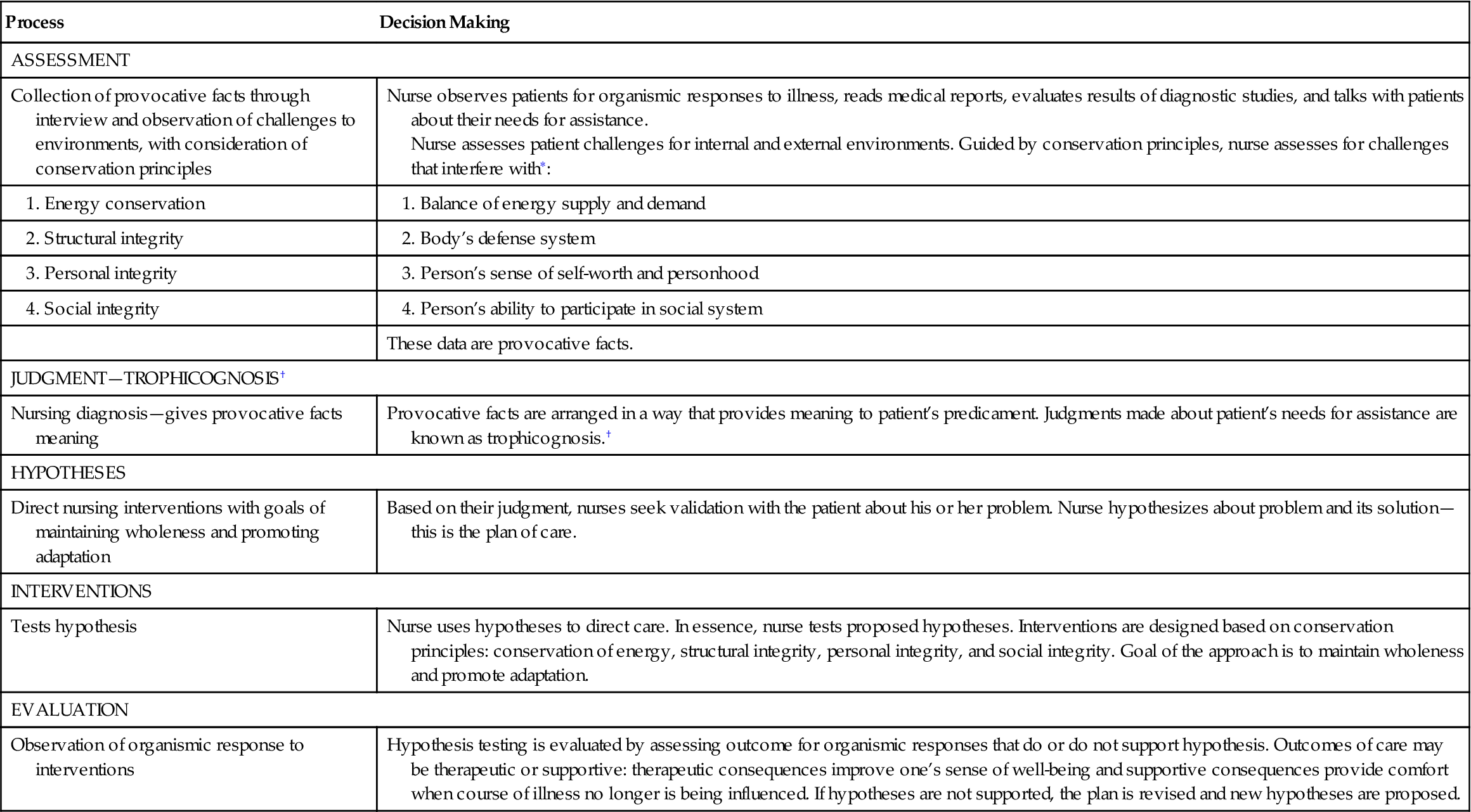

Levine (1973a,b) proposes that nurses use their scientific and creative abilities to provide nursing care to patients using a process incorporating ability to think critically. Table 10-1 describes Levine’s nursing process using critical thinking the nurse used to guide Debbie’s care.

TABLE 10-1

Levine’s Nursing Process Using Critical Thinking

| Process | Decision Making |

| ASSESSMENT | |

| Collection of provocative facts through interview and observation of challenges to environments, with consideration of conservation principles | Nurse observes patients for organismic responses to illness, reads medical reports, evaluates results of diagnostic studies, and talks with patients about their needs for assistance. Nurse assesses patient challenges for internal and external environments. Guided by conservation principles, nurse assesses for challenges that interfere with∗: |

| These data are provocative facts. | |

| JUDGMENT—TROPHICOGNOSIS† | |

| Nursing diagnosis—gives provocative facts meaning | Provocative facts are arranged in a way that provides meaning to patient’s predicament. Judgments made about patient’s needs for assistance are known as trophicognosis.† |

| HYPOTHESES | |

| Direct nursing interventions with goals of maintaining wholeness and promoting adaptation | Based on their judgment, nurses seek validation with the patient about his or her problem. Nurse hypothesizes about problem and its solution—this is the plan of care. |

| INTERVENTIONS | |

| Tests hypothesis | Nurse uses hypotheses to direct care. In essence, nurse tests proposed hypotheses. Interventions are designed based on conservation principles: conservation of energy, structural integrity, personal integrity, and social integrity. Goal of the approach is to maintain wholeness and promote adaptation. |

| EVALUATION | |

| Observation of organismic response to interventions | Hypothesis testing is evaluated by assessing outcome for organismic responses that do or do not support hypothesis. Outcomes of care may be therapeutic or supportive: therapeutic consequences improve one’s sense of well-being and supportive consequences provide comfort when course of illness no longer is being influenced. If hypotheses are not supported, the plan is revised and new hypotheses are proposed. |

∗Although the conservation principles guide the assessment of environmental challenges, this was not included in the original model. It is helpful for the novice nurse, in particular, to organize provocative facts in a manner that directs the hypotheses, as illustrated in the nursing care of Debbie. Experienced nurses integrate the assessment of the environments, as illustrated in the presentation of nursing care of Alice.

†Trophicognosis is a nursing care judgment deduced through the use of the scientific process (Levine, 1966b). The scientific process is used to make observations and select relevant data to form hypothetical statements about the patient’s predicaments (Schaefer, 1991).

Nursing Care of Debbie with Levine’s Model

Debbie is very concerned about her future and the future of her children. She requires nursing care and assessment of environmental challenges threatening her integrity and ability to adapt.

Challenges to Debbie’s Internal Environment

Challenges that reduce Debbie’s energy resources include her 20-pound weight loss and her cigarette smoking. She has had radical surgery, which challenges herstructural integrity. The loss of reproductive ability poses a possible challenge to her personal integrity. She is having difficulty completely emptying her bladder. Smoking and taking oral contraceptives on a regular basis pose risk. Her diagnostic studies and vital signs are additional indices of challenges to her internal environment.

Challenges to Debbie’s External Environment

Debbie reports her husband is emotionally distant and at times abusive. Considering this fact, the nurse reviews available patient records for Debbie, assessing for bruises, burns, or fractures that may have been noted on other health care visits. Debbie lives in a home that she describes as “less than sanitary” and has voiced concern about her own future as well as that of her children.

Assessment

Energy Conservation

Challenges that drain Debbie’s energy resources include recent weight loss, nausea, pain, and smoking. She has pain despite pain medication and she is concerned about care of her children.

Debbie’s structural integrity is threatened by a surgical procedure with potential for skin breakdown and infection. She is receiving an antibiotic prophylactically to prevent infection of the surgical wound. In addition, she is having difficulty emptying her bladder. Her risks include use of oral contraceptives, smoking, history of early childbirth, and recent diagnosis of cancer. On discharge, she is to undergo radiation therapy, which poses additional challenges of skin breakdown, destruction of normal cells, pain, and hair loss in the irradiated area.

Personal Integrity

Debbie feels her illness is punishment for past behaviors. The surgery and the consequences of surgery may jeopardize her sense of self-worth. Debbie is only 29 years old and she may have wanted more children. The impact of not being able to give birth could be devastating. Further, there is consideration of the impact of this situation on the family. Debbie recognizes her husband is emotionally distant and she wonders if he is capable of the emotional support she needs.

Social Integrity

Debbie will experience early menopause and the emotional and physical effects of that experience. Many young women her age have infants and menstrual cycles; she will not. Debbie also experiences anxiety and fear about her own future as well as that of her children. Debbie’s relationship with her husband may experience additional strain due to the emotional impact of the surgery on him and his potential to be abusive.

Judgments

The following 10 trophicognoses (diagnoses) are identified for Debbie:

Hypotheses

Using the conservation model the nurse proposes hypotheses about Debbie’s needs to develop a plan of care with her. The hypotheses might include the following:

• Providing Debbie with a nutritional consultation will help her find foods she can tolerate, increasing her energy level, strength, and healing capacity.

• Careful use of food and medicine for nausea will improve her tolerance for food.

• Teaching and return demonstration of urinary self-catheterization will reduce the potential for infection.

• Observation and cleansing of the surgical wound will reduce the chance for infection.

• Preparing Debbie for radiation treatment by discussing expected side effects and ways to minimize those effects will promote both structural integrity (maintenance of skin integrity) and personal integrity (sense of control).

• Encouraging Debbie to talk about her concerns and fears about having a hysterectomy will help her resolve fears, defuse myths, and prepare for some of the emotional/physical effects, including premature menopause.

• Visiting nurse follow-up (after discharge) will provide Debbie with emotional (sharing) and physical support (self-catheterization reinforcement).

• Teaching Debbie about her medications will maximize their effect (pain relief) and reduce the risk of potential side effects.

• Teaching alternate approaches for pain management (relaxation) will enhance the effects of the pain medication.

• Providing Debbie information about risky behaviors and ways to reduce those behaviors will give Debbie control over her health.

• Providing Debbie with time to talk about why she thinks her diagnosis is punishment for past behavior will help her understand that she did not cause her illness and subsequently will improve her sense of self-worth.

Nursing Interventions

When providing care to Debbie, the nurse uses the conservation principles to maintain wholeness and promote adaptation.

Energy Conservation

A nutritional consultation will assist Debbie in identifying foods that reduce nausea, improve caloric intake, and maintain required intake to meet her needs. If nausea continues, careful administration of the medication before eating may help reduce associated nausea. The frequency and intensity of pain may be controlled by identifying activities that aggravate her pain and offering medication to Debbie before she performs these activities. Because patients commonly experience fatigue after a total hysterectomy and radiation, Debbie will be prepared to expect fatigue and balance her activity and rest periods. Rest will become very important while her body heals.

Structural Integrity

Debbie’s wound is assessed for signs of healing. The antibiotic is administered as ordered, and she is given instructions on how to take it at home. The nurse stresses the importance of completing prescriptions as ordered. Debbie needs to learn self-catheterization; return demonstrations will improve her confidence in performing the task. Before discharge, Debbie is prepared for outpatient radiation treatments and the following three points are stressed:

1. The importance of laboratory work to monitor the body’s response to the therapy

2. The importance of skin protection to reduce irritation associated with the radiation

3. The importance of avoiding situations that support infection (e.g., a child with a cold) because of the body’s decreased ability to fight infection

Personal Integrity

Debbie is encouraged to talk about what having her uterus removed means to her. If she chooses to not discuss her feelings, the nurse respects Debbie’s privacy. Because Debbie feels that her illness is punishment for her past behavior, she needs to be reassured. A referral to a mental health nurse specialist is considered.

Social Integrity

The nurse assesses the potential for abuse from Debbie’s husband and considers family support. The nurse explores resources available in the community (e.g., church, support groups, shelters) to support Debbie and her family.

Organismic Responses

The nurse observes for the following possible organismic responses:

• Clean urinary self-catheterization

• Dialogue about how Debbie feels about a hysterectomy and cancer

• Improved appetite and weight gain

• Recognition that her past behavior did not cause her disease

• Restful sleep and increased energy

• Husband and children providing assistance within their capabilities

Nursing Care of Alice with Levine’s Model

Fibromyalgia (FM)—a chronic condition of widespread muscular pain and fatigue—is most commonly diagnosed in women to men at an approximate rate of 20:1 (Bennett, 2010). The symptoms mimic the flu and include muscle aches and pains, stiffness, nausea, insomnia, and fatigue (Bennett, 2003). However, in spite of these symptoms, most individuals with FM will have normal diagnostic studies.

According to Levine (1971a), nursing care focuses on maintenance of wholeness (integrity, oneness) and promotion of adaptation. Alice was open and discussedwhat she might be able to do for herself. She was desperate and frustrated because nothing seemed to help her. The continuous pain and fatigue were getting her down. She continued visiting her physician who ordered additional tests to ensure nothing new was causing her pain. In the interim, Alice continued to search for relief. Levine’s conservation model directs nurses to involve patients in decisions about their care.

As the nurse entered into a relationship with Alice, she asked Alice to describe her situation. Attention to environmental factors and integrities lead the nurse to ensure the patient’s sense of oneness during the initial encounter. Patients may doubt their integrity and come to believe, as Alice does, that they do not have control over their lives, they will not be taken seriously, and their concerns are not perceived as valid (Schaefer, 1995).

Challenges to Alice’s Internal Environment

Assessment revealed that Alice had “been treating pains for years.” Her diagnostic tests were normal. She reported a history of difficult menstrual periods, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), and migraine headaches. All physiological and pathophysiological aspects of her internal environment were normal.

Challenges to Alice’s External Environment

Alice noticed she experienced migraine headaches after eating Italian food and concluded she might be allergic to the sauce. She claimed she felt better since she had begun being more careful. This finding supported Levine’s notion that people seek, select, and test information from the environment in the context of their definition of self, thus defending their safety, identity, and purpose (Levine, 1991).

Adaptation to conceptual environment is sometimes threatened by a response that implies the complaints associated with the illness are not valid. Alice was fortunate that her physicians acknowledged her pain; however, family members had difficulty believing something really was wrong. Socially, she thought people viewed her as malingering, and she felt sorry for herself when unable to keep social engagements.

Judgment (Trophicognosis)

Alice was diagnosed with FM, a chronic illness about which little is known. The major problems are fatigue and pain, which threatens the ability to adapt and maintain wholeness. Considering the conservation principles, the nurse helped her adapt in a positive manner and return to a level of perceived wholeness.

Hypotheses

Using the conservation model, the nurse proposes hypotheses about Alice’s needs to develop a plan of care with her. The hypotheses might include the following:

• Encouraging combined use of pharmacological and nonpharmacological sleep interventions (relaxation, hot showers) will improve the subjective quality of Alice’s sleep and her energy level.

• Losing weight will help reduce Alice’s aches and pains.

• Keeping a diary of her symptoms and recording the internal and external environmental challenges to her integrity will improve Alice’s understanding of her unique patterns of FM.

• Teaching about the medications Alice can take for FM will help her use pharmacological interventions safely.

• Encouraging open, honest communication will help reduce Alice’s anger.

• When Alice feels better and engages in social activities she will feel better about herself.

Nursing Intervention

Energy Conservation

Both emotional stress and management of multiple responsibilities at work and home drained Alice’s energy. She elected to work part-time to avoid an environment that seemed unhealthy for her.

Alice recorded in her diary that she frequently had difficulty getting a good night’s sleep and noticed the more restless her night, the more pain she experienced in the morning. Sleep improved slightly when she used relaxation tapes to fall asleep. The nurse suggested sleep is often improved by taking a warm bath before bedtime, drinking warm milk at bedtime, and avoiding heavy foods 3 to 4 hours before bedtime. Alice was encouraged to establish a bedtime routine to be practiced daily because routine is critical to these interventions.

When discussing ways to improve Alice’s sleep, the nurse reviewed the drugs Alice was taking and their possible effects. It was at that time Alice indicated she had a prescription for an antidepressant but chose not to take it. The nurse informed Alice that the drug frequently helped reduce the severity and frequency of pain and that it takes up to 3 weeks to notice the benefits. She also shared that women have stopped taking the drug because of inability to tolerate side effects. They reviewed the side effects of dry mouth, feeling “hung over,” fast pulse rate, and constipation, and the nurse noted that eating a diet with grains and vegetables, taking the medication 1 to 2 hours before bedtime, and drinking 10 glasses of water a day reduce side effects. Alice found that if she took the drug every night she felt much better and had more energy. She subsequently was able to plan social outings without the constant fear that she would have to cancel her plans because of pain and fatigue.

Alice had learned to pace activities when she had a lot to do. This included planning for additional sleep during times of stress (e.g., deadlines at work, illness, menstrual periods). When sleep was not possible, rest and relaxation, such as slow, rhythmic breathing and imagery, were suggested to replenish energy.

Alice was about 10 pounds overweight. She agreed to try to slowly lose some of the weight. Her physician believed that the weight reduction would reduce the strain on Alice’s back and help control her aches and pains. Alice had noticed that foods such as tomatoes or spices precipitated her headaches; therefore, she was encouraged to keep a record of foods she ate and her pattern of symptoms.

A subsequent review of Alice’s diary, reported experiences, and correlation analysis revealed that weather changes lagged the pain and fatigue by up to 2 days. This helped Alice to realize some pain and fatigue was temporary and decreased as the weather changed. This understanding helped her deal with discomfort in a more positive way, such as getting more rest when challenged by external environmental factors.

Structural Integrity

Alice understood that uncertainty about the symptoms necessitated ruling out other illnesses to ensure appropriate interventions. Because Alice was taking antidepressants, she knew about the possibility of weight gain, dry mucous membranes, and constipation. She needed to eat complex carbohydrates to reduce the hunger associated with increased serotonin levels. Drinking more water and eating a balanced diet may reduce the dryness and constipation. Heart rate changes, associated with some antidepressants, should be reported to the physician or nurse practitioner. She was reassured that alternative medications are available if she is unable to tolerate the prescribed drug. Because she expressed interest in homeopathy, she was warned about herbs and over-the-counter remedies that may be harmful and encouraged not to take them without supervision. She was encouraged to continue taking warm showers in the morning and listening to her tapes at night. Since she admitted having a few alcoholic drinks before bed, she was encouraged to limit herself to two drinks a day and to avoid drinking 3 hours before bedtime.

Personal Integrity

Regaining a sense of selfhood for Alice meant being able to do things around the house and enjoy social events with her husband and family. She expressed satisfaction that she “seemed to be getting better” and could participate in most of her desired activities.

Social Integrity

Alice was encouraged to join a support group. Alice stated it was exciting to be in a support group because she met people who have the same problem, she learned a lot about her illness, she liked interacting with the other members, and she felt good when she attended meetings. Alice is an outgoing person and with her pain under control she has been able to reach out to others in the group. It is important to encourage the patient to communicate openly and honestly. Alice felt that her husband did not understand her illness; he simply tolerated it. This not only made her angry but also gave her cause for concern about their marriage. After Alice attended the support group and shared her positive experience with her husband, she had her first “emotional feeling” talk with him in years and felt good about this.

Organismic Responses

Success of the interventions is measured through the observation of organismic responses. Responses observed in Alice included the following: