Modeling and Role-Modeling Theory in Nursing Practice

Margaret E. Erickson

Modeling and Role-Modeling is based on the philosophy that all humans have the desire to live healthy, happy lives, to find meaning and purpose in their lives, and to become the most that they can be. This holds true across the lifespan. When we use strategies that focus on the strengths of our clients, help them become more fully alive (even as they approach physical death), and to live their lives to the fullest, then we are truly helping them grow, heal, and transcend. We help them discover the essence of their being, to find or reclaim their soul.

History and Background

The Modeling and Role-Modeling (MRM) paradigm, conceived by Helen Erickson in the late 1950s, was an outcome of her exposure to the work of her father-in-law, Milton H. Erickson, coupled with her own experiences as a professional nurse. During the late 1940s and the 1950s, M. Erickson, MD, developed an international reputation for his unorthodox methods, views on human nature, and clinical results (Rossi & O’Ryan, 1985, 1992; Rossi, O’Ryan, & Sharp, 1983). H. Erickson states that she repeatedly asked him to tell her “what to do and how to do it” (H. Erickson, personal communication, February 2000). She hoped for protocols, treatment recommendations, and quick fixes, but instead she was told that she must model the client’s world and plan strategies within that context. M. Erickson, MD, advised that each human has a unique view of the world and needs to maintain his or her role in unique ways and that the practice of health care professionals was to help clients succeed in living quality lives and growing to the maximum of their potential.

Over a period of approximately 16 years, H. Erickson came to understand the wisdom of her father-in-law’s advice. As a result, by the mid-1970s, she hadconceived and developed a practice framework that she called Modeling and Role-Modeling. She began to label and articulate the theoretical components during her baccalaureate completion and master’s study at the University of Michigan (1972-1976). Refinement of the concepts and their linkages continued as she worked with and was challenged by two colleagues, Mary Ann Swain and Evelyn Tomlin.

H. Erickson’s first independent research study occurred during graduate school. Under Swain’s supervision, a study was designed to test the Adaptive Potential Assessment Model (APAM) (Erickson, 1976), which had been conceived, labeled, and articulated in the mid-1970s (Figure 16-1). Concurrently, Swain and Erickson collaborated on another project designed to test the effects of MRM nursing interventions with persons who had hypertension. This work led to a third study that explored the effects of using MRM with persons who had diabetes (Erickson & Swain, 1982). Tomlin joined the research team for this project.

During these years Erickson also expanded and tested the concept of self-care knowledge (Erickson, 1984, 1990) that was conceived during the 1960s and early 1970s. She presented numerous papers, consulted in various agencies, taught at the University of Michigan, and continued her independent practice. Tomlin continued to explore ways to apply MRM in practice and to teach the theory and paradigm to undergraduate students while Swain supervised Erickson’s research, collaborated with her on further elaboration of the theory, and facilitated the administrative phase of Erickson’s career.

Finally, innumerable requests for written materials from practicing nurses, students, and faculty mandated that the book Modeling and Role-Modeling: A Theory and Paradigm for Nursing be written. After the book was published, it was used as a text at the University of Michigan. Undergraduates were taught the basic premises; several university hospital units adopted it as a guide for practice (Walsh, Vandenbosch, & Boehm, 1989); a modified assessment form was developed at the University of Michigan Medical Center (Campbell, Finch, Allport, et al., 1985); graduate students used it to guide their master’s theses (Calvin, 1991; Finch, 1987; Hannon & McLaughlin, 1983; Smith, 1980; Walker, 1990); and doctoral students used it for their dissertations (Acton, 1993; Baas, 1992; Baldwin, 1996; Barnfather, 1987; Beltz, 1999; Benson, 2003; Boodley, 1986; Bowman, 1998; Bray, 2005; Chen, 1996; Clayton, 2001; Curl, 1992; Daniels, 1994; Darling-Fisher, 1987; Dildy, 1992; Erickson, 1996; Hertz, 1991; Holl, 1992; Hopkins, 1994; Irvin, 1993; Jensen, 1995; Keck, 1989; Kennedy, 1991; Kline, 1988; Landis, 1991; MacLean, 1987; Miller, 1994; Miller, 1986; Nash, 2004; Raudonis, 1991; Robinson, 1992; Rogers, 2003; Rosenow, 1991; Scheela, 1991; Sofhauser, 1996; Straub, 1993; Weber, 1995). These studies helped identify and support many of the theoretical concepts and proposed midrange theories.

The Society for the Advancement of Modeling and Role-Modeling

In 1986, a website (www.mrmnursingtheory.org) was established by a cohort of students, faculty, and practitioners, and national biennial conferences were initiated. The first conference was co-sponsored by the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor in 1986, followed by the University of South Carolina at Hilton Head in 1988, and the University of Texas at Austin in 1990. National conferences continue to be held biennially. The Society for the Advancement of Modeling and Role-Modeling was established in 1986.

Schools and health care organizations—including, but not limited to Metro State University in St. Paul, Minnesota; State University of New York at Buffalo; University of Tennessee at Knoxville; Capital University, Columbus, Ohio; St. Catherine’s Hospital in Minneapolis, Minnesota; Lamar University, Joanne Gay Dishman Department of Nursing, Beaumont, Texas; the University of Texas at Austin, Galveston, and Brownsville; and others—have adopted and use MRM as the bases for either parts or all of their nursing curricula. In addition, health care agencies throughout the country such as the University Health System in Knoxville, Tennessee, or Salina Regional Health Center, Salina, Kansas, have applied MRM to implement and guide holistic nursing practice (Alligood, 2011; Perese, 2002).

Continued research has provided support for several of the middle-range theories proposed in MRM. The three states of the APAM model have been tested and found to be independent of one another and predictors for stress (Barnfather, 1990; Barnfather, Swain, & Erickson, 1989a,b; Erickson & Swain, 1982, 1990). Relationships have been shown between the following: stress and needs status (Barnfather, 1990, 1993); needs status and developmental residual and hope (as developmental residual) (Curl, 1992); burden and affiliated-individuation in caretakers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease (Acton, 1993); needs satisfaction (Leidy, 1994); needs and affiliated-individuation (Acton & Miller, 1996); stressand affiliated-individuation (Irvin & Acton, 1996); perceived support, control, and well-being in the elderly (Chen, 1996); and stress, psychological resources, and physical well-being (Leidy, 1989, 1990).

Several studies also have been conducted to explore perceived enactment of autonomy (PEA) in the elderly (Hertz & Baas, 2006), PEA and self-care, and holistic health in the elderly (Anschutz, 2000; Anschutz & Hertz, 2002); PEA and related socioeconomic factors among noninstitutionalized elders (Hwang & Lin, 2004); and PEA, self-care resources, among seniors (Matsui & Capezuti, 2008).

Other studies have provided support for linkages between role-modeled interventions and outcomes (Acton, 1993; Acton, Irvin, Jensen, et al., 1997; Erickson, 1996, 2006; Erickson, Thomlin, & Swain, 1983; Hertz, 1991; Holl, 1992; Hopkins, 1994; Irvin, 1993; Jensen, 1995; Keck, 1989; Kennedy, 1991; Kline, 1988; Scheela, 1991).

Instruments have been developed to enhance application of MRM in practice and research. Tools include those designed to measure the following: needs status (Leidy, 1994); developmental residual (Darling-Fisher & Leidy, 1988); the APAM stress states using content analysis (Hopkins, 1994); self-care resources of cardiac patients (Baas, 1992, 2011); denial in postcoronary patients (Robinson, 1992); perceived enactment of autonomy in the elderly (Hertz, 1991); family experience with eating disorders (Folse, 2007); patients’ adjustment to implanted cardiac devices (Beery, Baas, Mathews, et al., 2005); and the bonding-attachment process within the context of needs satisfaction in teenage mothers (Erickson, 1996).

This theory also can be applied in all settings and with all populations. MRM has been used to provide a theoretical foundation for exploration and examination of how persons ages 85 and older manage their health (Beltz, 1999), quality care of diverse older adults (Hertz, 2008); urinary incontinence and assessment of the Bladder Health Program among rural elders (Liang, 2008, 2011); to achieve greater understanding of families’ experience through prolonged periods of suffering and their evolution toward spiritual identity (Clayton, 2001); caring for people living with advanced cancer (Haylock, 2010); finding meaning in life (Clayton, Erickson, & Rogers, 2006; Erickson, 2006); living with mental health disorders (Hagglund, 2009; Sung & Yu, 2006); mentoring students (Lamb, 2005); and coping with stress (Benson, 2006). Benson’s application of MRM was supportive and provided insight into the subsequent use of APAM in small groups (Benson, 2003, 2011). MRM also has provided a foundation for exploration of how patients adjust to implanted cardiac devices (Beery, Baas, & Henthorn, 2007).

Researchers have used this holistic nursing theory and paradigm to explore the following situations: lived experiences and perceptions of hope of elementary children in urban areas (Baldwin, 1996); the experience and perceptions of mothers using child health services in South Africa (Jonker, 2012); the meaning of encouragement and its connection to the inner-spirit perceived by caregivers of the cognitively impaired (Miller, 1994); the evaluation of holistic peer education and support group programs aimed at facilitating self-care resources in adolescents (Nash, 2004, 2007); the experiential meaning of well-being for employed mothers (Weber, 1995); the relationship between psychosocial attributes, self-care resources, basic needs satisfaction, and measures of cognitive and psychological health ofadolescents (Bray, 2005); psychosocial aspects of heart failure management (Baas & Conway, 2004); and self-care resources and activity as predictors of quality of life in person’s with post-myocardial infarction (Baas, 2004). In addition, holistic healing for women with breast cancer through a mind, body, and spirit self-empowerment program (Kinney, Rodgers, Nash, et al., 2003); morbid obesity (Lombardo & Roof, 2005); patient’s perceptions regarding nurse-client interactions (Rogers, 2003), the relationship between basic need satisfaction and emotional eating (Cleary & Crafti, 2007; Timmerman & Acton, 2001) has been studied using MRM.

Finally, research has been conducted to further explore major constructs or philosophical assumptions in the MRM theory. Baas, Beery, Allen, and colleagues (2004) studied self-care knowledge in patients with heart failure and transplant; Baldwin (2004) studied self-care for clients in early menopause; Baldwin and Herr (2004) studied the effect of self-care on treatment of interstitial cystitis; Baldwin, Hibbeln, Herr, and colleagues explored self-care as defined by members of an Amish community (2002); and Beery, Baas, Fowler, & Allen (2002) studied spirituality in persons with heart failure.

Overview of Modeling and Role-Modeling

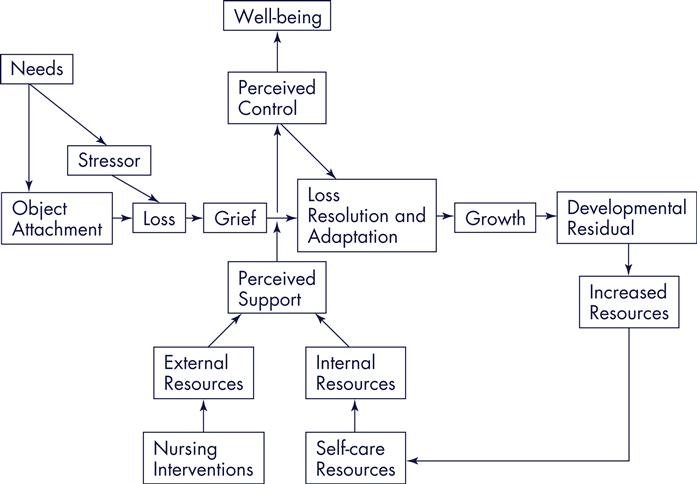

Modeling and Role-Modeling (Erickson, et al., 1983 [reprinted in 2002]), conceived within the context of numerous philosophical assumptions, was labeled and articulated by Erickson synthesizing several concepts from established theories. Concepts were drawn from the works of Maslow (1968, 1970), Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1980), Erikson (1963), Engel (1962, 1968), and Selye (1974) to create a new theory that described relations among needs, loss, grief, adaptation, developmental processes, growth, and well-being of the holistic person (Figure 16-2). The practice paradigm was derived from integrating philosophical assumptions with theoretical underpinnings.

Philosophical Assumptions and Constructs

Holism

Humans consist of cognitive, biophysical, social, and psychological subsystems permeated by genetic predispositions and a spiritual drive (Figure 16-3). The ongoing interaction of these multiple components creates a dynamic, holistic system that is greater than a sum of the parts (Erickson, Tomlin, & Swain, 2005). Health, which is affected by these dynamic interactions, is a perception of well-being, as perceived by the client. Although physical status influences perceptions of health, persons can perceive a high level of well-being even as they take their last breath. Therefore, health can be defined as a dynamic, eudaemonistic sense of well-being (Erickson, et al., 2005) associated with self-fulfillment and transcendence beyond the objective reality of the moment (Erickson, 2001).

Affiliated-Individuation

Essential to a person’s sense of well-being is the need for affiliated-individuation (AI). AI, coined by Erickson, is defined as “the need to be dependent on support systems while simultaneously maintaining independence from these support systems (Erickson, et al., 1983, p. 252). AI is usually first recognized, and acceptedas normal, during the stage of autonomy as a toddler explores the world but reconnects regularly with his or her care provider. Although AI is a lifelong need for all people, it is commonly not recognized as acceptable behavior as people get older and are expected to be independent.

Need Satisfaction, Growth, and Development

Humans are in a continual state of change and have inherent drives that motivate behavior. These include a drive for needs satisfaction, adaptation, and growth sequential development. According to Erickson and colleagues (2005), “Growth is defined as the changes in body, mind, and spirit that occur over time” (p. 46) and facilitates an individual’s development. Development is defined as “the holistic synthesis of the growth-produced…differentiations in a person’s body, ideas, social relations, and so forth” (Erickson, et al., 1983, p. 47). When individuals are given necessary information, adequate emotional support, and are empowered in making satisfactory decisions, growth and subsequent development occur and health is enhanced.

Internal and External Resources

According to the MRM paradigm, the nurse facilitates an interactive, interpersonal relationship with the client. During this process the nurse assists the client inidentifying, developing, and mobilizing internal and external resources—resources needed to cope with life’s stressors, to grow and heal. Essential to this process is the nurse’s unconditional acceptance of the client. Erickson and colleagues (1983) argue that “[b]eing accepted as a unique, worthwhile, important individual—with no strings attached—is imperative if the individual is to be facilitated in developing his or her own potential” (p. 49).

Modeling

In a supportive and caring environment, a nurse attempts to understand “the client’s personal model of his or her world and to appreciate its value and significance for the client from the client’s perspective” (Erickson, et al., 1983, p. 49). The act of developing an image and understanding of the clients’ worldviews from within their perspectives and framework is called modeling. “The way an individual communicates, thinks, feels, acts, and reacts—all of these factors comprise the individual’s model of his or her world” (Erickson, et al., 1983, p. 84).

Role-Modeling

After the client’s world has been modeled, the nurse facilitates and nurtures the individual “in attaining, maintaining, or promoting health through purposeful interventions” (Erickson, et al., 1983, p. 254). This is known as role-modeling. In role-modeling the client’s world, the nurse plans interventions that do the following:

These interventions are aimed at helping the client “achieve an optimal state of perceived health and contentment” (Erickson, et al., 1983, p. 49).

Self-Care Knowledge, Self-Care Resources, Self-Care Actions

Nursing interventions are designed based on the belief that all individuals at some level understand what has interfered with their growth and development and altered their health status. Accordingly, people also know what they need to improve and optimize their state of health, facilitate their growth and development, and maximize their quality of life and well-being. This inherent knowledge is called self-care knowledge. Individuals also have internal and external self-care resources. Internal self-care resources (or self-strengths) refer to all of the “internal resources that an individual can use to promote health and growth” (Erickson, et al., 1983, p. 128). These strengths are defined by the perceptions of both the nurse and the client and can include attitudes, endurance, patterns, or whatever else is perceived to be a personal strength and resource of that individual. External self-care resources include the client’s social network and support systems. The social network is a set of individuals with whom the client is socially acquainted, and support systems are a set of individuals who are perceived to support, energize, and provide resources for the client.

Development and utilization of self-care knowledge and self-care resources is known as self-care action. “Through self-care action the individual mobilizes internal resources and acquires additional resources that will help the individual gain, maintain, and promote an optimal level of holistic health” (Erickson, et al., 1983, p. 49).

Finally, an individual’s potential for mobilizing resources and achieving a state of coping is directly related to his or her level of needs satisfaction (Erickson, et al., 1983). Individuals who have a high level of needs satisfaction have a greater ability to positively cope with life’s stressors and to achieve a state of equilibrium. However, individuals who have a high level of unmet needs have less ability to mobilize resources and are at risk when confronted with stressors.

Nursing interventions are designed to facilitate clients in using self-care actions that will help them meet their physiological, psychological, social, cognitive, and spiritual needs. Repeated needs satisfaction results in growth; continued growth produces healthy developmental residual. Fundamental to this theory is the understanding that an individual’s needs are met only when the individual perceives that they are met.

Theoretical Underpinnings

Developmental processes are sequential tasks, strengths, and virtues that are associated with biological time periods (Figure 16-4). Each stage has a central focusand related life task to be accomplished. The manner in which this task is completed will determine what type of developmental residual results. Residual from stage one serves as a resource (or hindrance) for task resolution of stage two, and so forth across the life span. Because of the epigenetic nature of the developmental processes, people are constantly reworking earlier stages. One’s ability to resolve developmental tasks in a healthy manner (and to rework earlier acquired residual) is dependent on resources accrued from having one’s needs met across the life span.

Need Satisfaction, Growth, and Development

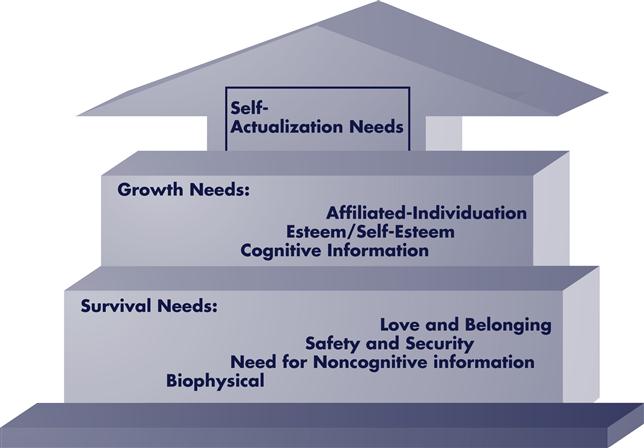

Inherent needs, classified as survival, AI, or growth-related, emerge in a quasi-ordered manner. Lower-level needs must be satisfied to some degree before higher-level needs emerge (Figure 16-5). Minimal lower-level and mid-level needs satisfaction is necessary for survival; repeated needs satisfaction facilitates growth and development. Lower-level and mid-level needs deficits create tension and drive behaviors aimed at meeting those unmet needs; satisfaction of these needs dissipates the tension. Higher-level needs satisfaction creates tension and desirefor additional growth experiences. People who repeatedly experience unmet needs during the early years of life develop a deficit motivation toward relationships. Those who repeatedly experience needs satisfaction during the early years of life develop a being motivation.

Unmet Needs as Stressors and Stress Responses

Unmet needs are stressors; stressors produce stress responses. Resolution of stress requires adequate resources; one’s ability to mobilize adequate resources determines the outcome of the stress response. Stressors, stress responses, and resources may be within the same subsystem; however, they are not limited to a single subsystem. For example, an individual may experience an accident that can affect his or her physiological subsystem, or depending on the severity and the client’s perception of the event, it may affect the client’s physiological, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual subsystems.

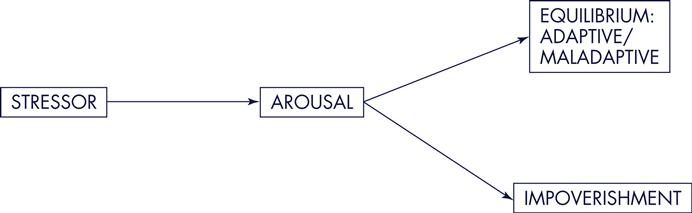

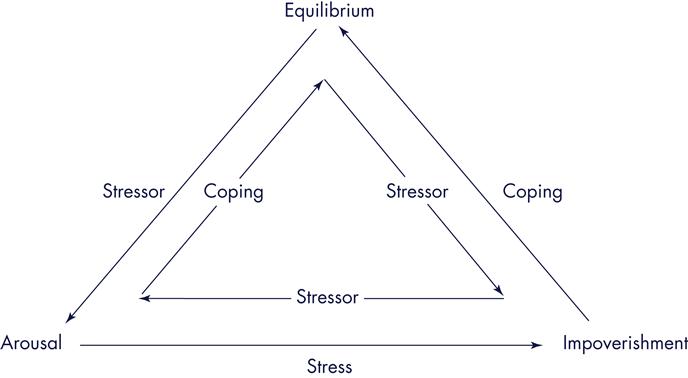

Stress Response States: Arousal and Impoverishment

The two types of stress response states are arousal and impoverishment. When adequate resources are available and readily mobilized, arousal occurs (Figure 16-6). When inadequate (or diminished) resources are available, impoverishment occurs. Those in impoverishment are at greatest risk for continued stress, depletion of resources, and resulting illness, disease, and/or physical death than are those in arousal (see Figure 16-6).

Adaptation, Attachment Objects, Loss and Grief Response

Adaptation occurs as needs are met, stress responses are diminished, and new resources are built. Those objects that repeatedly meet needs become attachment objects. These objects change as people move through various developmental stages. When attachment occurs, loss of attachment objects will result in feelings of loss. Loss can be situational and developmental. Loss is real, threatened, or perceived. Examples of situational losses are the loss of a favored item, the perceived rejection by a loved one, or a major flooding of one’s home. Developmental losses are phases of movement through the developmental sequence, such as weaning during infancy, going to school, or leaving home. When loss occurs—whether it is real, threatened, or perceived—people experience grief.

The grief process has sequential phases; movement through the grief process requires mobilization of resources. One’s ability to mobilize adequate resources determines the outcome of the grief response. Inadequate resources and one’s inability to deal with a loss result in morbid grief (Lindemann, 1942); morbid grief affects future developmental processes, as Box 16-1 illustrates. A synthesis of these multiple theories provided the bases for the MRM theory. Major theoretical linkages are shown in Box 16-1.

Critical Thinking in Nursing Practice with the Modeling and Role-Modeling Theory

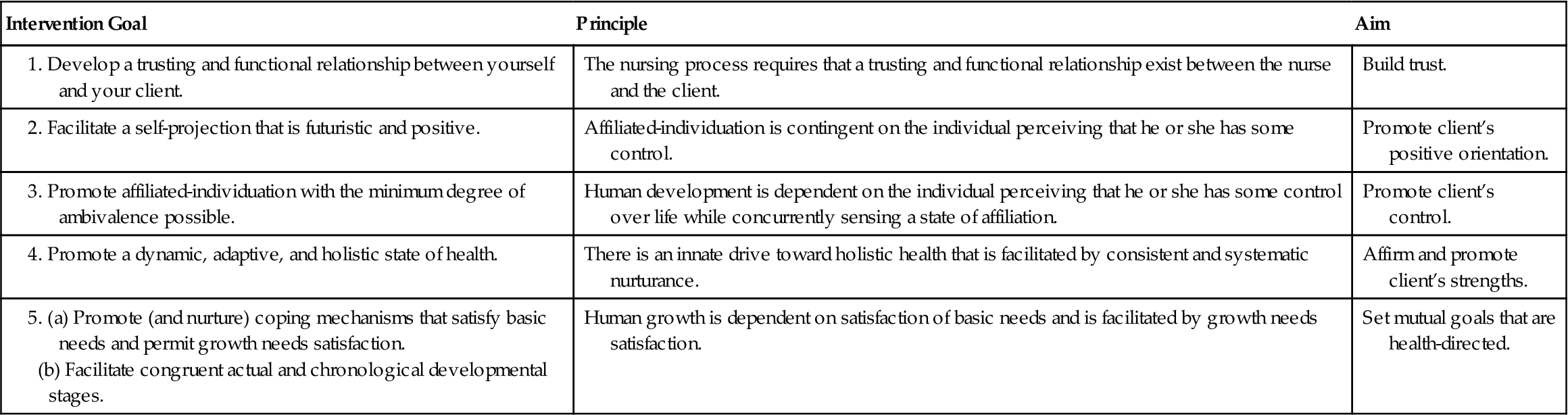

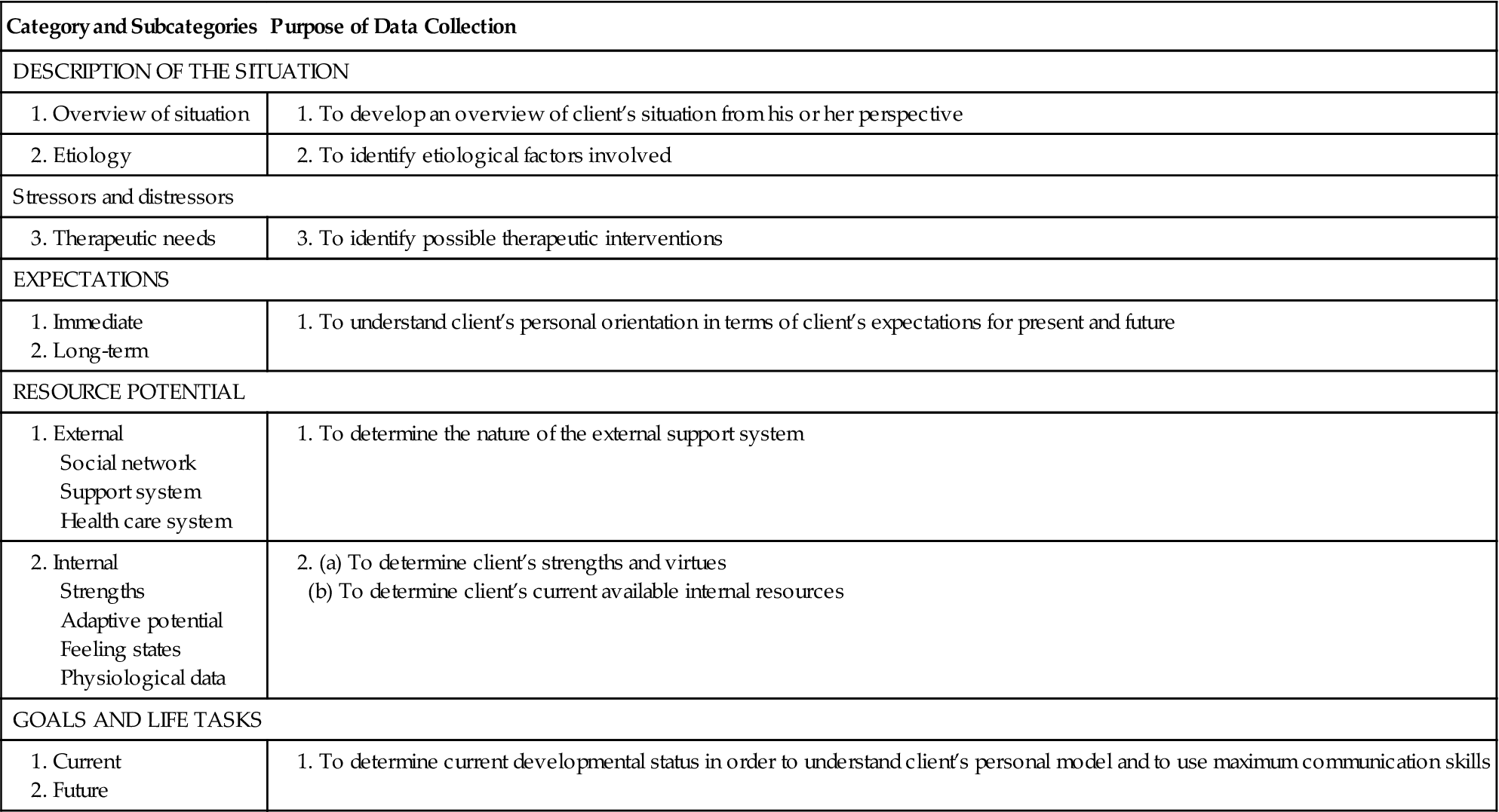

The MRM practice paradigm is guided by five related nursing principles, intervention aims, and outcome goals for the nursing process (Table 16-1). There are interview guidelines that influence the type of data collected and specify the purpose of the data (Table 16-2). Table 16-3 illustrates the process for each phase of assessment. It discusses the data interpretation and analysis that lead to nursing impressions.

TABLE 16-1

Nursing Principles, Aims, and Goals

From Erickson, H., Tomlin, E., & Swain, M. (1983). Modeling and role-modeling: A theory and paradigm for nursing. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Appleton & Lange, with permission from Helen Erickson, Austin, TX. Reprinted (1988, 1990, 1994, and 1999). Ann Arbor, MI: ETS.

TABLE 16-2

Interview Guidelines and Purpose for Data Collection

| Category and Subcategories | Purpose of Data Collection |

| DESCRIPTION OF THE SITUATION | |

| Stressors and distressors | |

| EXPECTATIONS | |

| RESOURCE POTENTIAL | |

| GOALS AND LIFE TASKS | |

Modified from H. Erickson. (2001). From Erickson, H., Tomlin, E., & Swain, M. (1983). Modeling and role-modeling: A theory and paradigm for nursing. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Appleton & Lange, with permission from Helen Erickson, Austin, TX. Reprinted (1988, 1990, 1994, and 1999). Ann Arbor, MI: ETS.

TABLE 16-3

Data Analysis Methods, Interpretation, and Nursing Impressions

| Assessment Phase | Nursing Interventions | Nursing Impressions |

| Description | Write a paragraph on the relationship among the factors. Include comments that state client’s perceptions, identified stressors, distressors, perceptions of loss, congruency of this perception with that of secondary and tertiary resources, mind-body relationships, and associated subsystem. Identify possible therapeutic interventions, desire for information; include congruency with family and health care providers. |

Basic need assets/deficits Growth need assets/deficits Attachment/loss status Affiliation status |

| Expectations | Write a paragraph regarding client’s positive orientation. Include expectations for immediate nurse-client relationship, projection of self into future, extent of projection and nature of projection, sense of self as worthwhile, valued person, role of self in future. |

Self-futurity |

| Resource Potential: External | Write a paragraph on client-family relationship in their social network. State whether relationship is invigorating or draining; comment on availability of a significant other and mode of communication with other. Comment on perceived control in respect to others (i.e., ability to satisfy needs and resolve problems and dependency on others). Comment on past use of health care providers and perceptions of health care providers. | Affiliation Individuation Perceived control |

| Resource Potential: Internal | Write a paragraph on client’s strengths and virtues, which includes both universal and unique individual strengths and virtues. Describe feelings and patterns, length of time of feeling pattern. | Assets, APAM, developmental status, psychological, cognitive |

| Goals | Write a paragraph on planned goals, factors that facilitate, and barriers that inhibit. State chronological/current task. Note the type of cognitive processing used. |

APAM, Adaptive Potential Assessment Model.

Copyright Helen Erickson. (2001). Reprinted with permission from Helen Erickson, Austin, TX.

Data Collection, Interpretation, Analysis, Synthesis, and Application

Critical thinking occurs continually in the process as the following steps occur: data are collected, interpreted, analyzed, and synthesized; strategies are planned and used to facilitate growth and healing; and the caring process is evaluated to determine whether a healing process has been initiated. The primary source of information is the client; secondary sources include the family’s view and the nurse’s observations. Tertiary sources are all others, including medical information. The client’s self-care knowledge is considered primary information and is the initial focus of the nursing assessment. As the nurse uses an unstructured interview to collect self-careknowledge (primary data), both verbal and nonverbal communications are noted. A continuous appraisal of congruence is determined when nonverbal messages indicate lack of congruence with verbal statements; the interviewer stores this information for further consideration (Erickson, 1990; Erickson, et al., 1983). Having clients share “their life story” is one way to obtain rich, detailed primary data.

Secondary data are collected from the family or significant others and, when needed, additional data (tertiary data) are collected from other sources, such as the medical record, physicians, or other health care providers. These data are interpreted individually and then integrated to determine congruency among the sources, differing views, and other information. The primary source of data (self-care knowledge) always serves as the primary focus of nursing care. When there are differences in views, information, and orientation among the data sources, the nurse accepts the responsibility of working with the secondary client after first addressing the needs of the primary client. The MRM nurse also provides leadershipfor the interface between these three sources (primary, secondary, and tertiary) of information. That is, MRM nurses serve to facilitate better understanding of the client’s self-care knowledge and vice versa among other members of the team.

Although critical thinking is usually considered a scientific process, MRM practitioners also use critical thinking during the artistic phase of the caring process. That is, practitioners use critical thinking during the strategy implementation phase as well as during the previous phases of the process. Although specific strategies can be used to facilitate growth and healing, they are always applied within the context of the client’s worldview (Erickson, 2000, 2001; Erickson et al., 2005). That is the artistic aspect of MRM.

Nursing Care of Debbie with Modeling and Role-Modeling

Data Aggregation and Interpretation

Primary Data

Debbie’s self-care knowledge is not discussed. Therefore, the logical first step would be to return to Debbie and ask for her description of the situation, related factors, expectations, resources, and goals. These data would then be integrated with secondary and tertiary data to determine the appropriate course of action. However, because Debbie made “reported” comments, these can be integrated with obvious secondary and tertiary data.

Secondary and Tertiary Data

Description of the situation

According to the report, Debbie is distressed and depressed about her current life situation. Physically, she has just undergone major surgery and is experiencing postoperative pain, nausea, difficulty emptying her bladder, and a recent significant weight loss. No data are providedregarding Debbie’s ability to complete self-catheterization; her feelings about the multiple losses associated with her altered body image, need for self-catheterization, and inability to have children in the future; her discomfort associated with postoperative pain and nausea; and her fear of the future regarding her radiation treatment and the potential for recurrence of the cancer. Furthermore, no information is provided on personal or professional resources available to help her meet these needs.

Psychologically, Debbie is depressed and blames her current life situation on her past life transgressions. She believes that this illness is punishment for her past life. It is difficult to know if Debbie is referring to having been an adolescent mother, having smoked cigarettes since she was 16 years old, or other perceived transgressions. It would be important to ask her if she could share more information regarding this statement so that relevant data could be collected.

Debbie has experienced multiple losses recently and over the past several years that have resulted in needs deficits related to unmet love and belonging needs. As an adolescent mother, Debbie had little time to care for herself. At a time in her life when she needed to focus on who she was and on meeting her own needs, her resources were directed toward the care of two small children. This conflict of interest might have resulted in feelings of loss and related unmet needs (Erickson, 1996). In addition, she describes her marital relationship as emotionally distant and at times abusive. Consequently, she has received little if any social and emotional support from her husband. No data concerning her relationship with her mother and children are available. Further information is needed before it can be determined whether these individuals are perceived as supportive and help meet her basic love and belonging needs.

Debbie has multiple stressors and distress in her life. She is the mother of a preadolescent and an adolescent; her husband is unemployed; and her housing accommodations are unsanitary and unacceptable. She has had surgery, is nauseated, is in pain, is unable to void normally, and must learn intermittent self-catheterization. Her husband’s unemployment and her low educational level affect their ability to achieve financial freedom and security. Subsequently, they are dependent on her mother for a place to live. Inability to provide a home for her children and one in which she feels safe to live is an additional loss Debbie faces. These losses indicate basic physiological, safety and security, and self-esteem needs deficits. Furthermore, surgery and related costs will only exacerbate an already difficult financial situation. Under the circumstances, it is highly possible that Debbie does not have health insurance, which is an additional stressor. Major physical alterations in her body, weight loss, surgery, nausea, pain, and problems with voiding are all real losses.

Expectations

Debbie has not offered any immediate or long-term expectations. However, she has expressed great concern over her future and the future of her children. These findings suggest impoverishment, unresolved losses, and threatened future loss. Because we do not have primary data (self-care knowledge), we do not know whether these are related to basic physiological, safety and security, or love and belonging needs secondary to her current health status, living situation, or interpersonal relationships. No information from the othersources regarding her expectations is provided. The health care providers have identified their expectations for her as follows:

Resource potential

Debbie’s social network includes her mother, husband, and two children, who are approximately 13 and 11 years old. No information regarding her support system is provided except that her husband is emotionally distant and abusive. Debbie is receiving postoperative care in an oncology unit. She has provided no data on the care she has received during her hospitalization, the nurse-client relationship, or her interpersonal family dynamics, including whether her family members are physically and emotionally accessible for her needs.

Debbie, who is extremely tearful, shares that she has not been performing breast self-examinations and that she has completed the eighth grade. She has not verbalized any personal strengths. Debbie has demonstrated some responsibility. She has cared for her children and practiced birth control for the past 11 years.

Goals and life tasks

Debbie has not identified any goals, although she has expressed concern about herself and the future of her children. Future goals will need to focus on helping Debbie meet her basic needs and helping her work on the developmental task of autonomy. The nurses’ goals for Debbie include antibiotic therapy to prevent an infection, an antiemetic to help control nausea, and radiation therapy to destroy any remaining cancerous cells. No interventions to help her meet her basic or growth needs are identified.

Data Integration and Analysis

Debbie has recently experienced multiple losses that have affected her basic and growth needs satisfaction. Unfortunately she has minimal resources, so her ability to adapt to her current circumstances and achieve health and well-being is unlikely; she is impoverished. She is at high risk for further decline in her health status because of her inability to mobilize resources. Nursing interventions need to focus on helping Debbie achieve AI and basic and growth needs satisfaction.

Living at home, being married to a distant and abusive husband, having quit school after eighth grade, and lacking physical care of self all suggest that Debbie may be working on the developmental stage of autonomy versus doubt. Her life situation indicates that Debbie is having difficulty with AI. She has been unable to complete the education necessary to become financially independent. Debbie’s family is residing with her mother. She is married to a man who does not meet her financial or emotional needs. She was an adolescent mother. All of these factors indicate her difficulty in being autonomous and simultaneously having healthy connections (or feelings or affiliation) with her significant others.

Nursing Impressions

Debbie has multiple survival, growth, and self-actualization needs deficits. She is in morbid grief, probably secondary to early life experiences. These are compounded by her recent and current life situation. She lacks a secure attachment object and thus suffers from inadequate AI. She cannot positively project herself intothe future and has diminished resources; therefore, she is impoverished. Her collective situation suggests that she has minimal trust and (developmental) residual, unhealthy shame and doubt, guilt, and inferiority. She probably has difficulty with role confusion as well. She is currently confronted with the task of intimacy and appears to have more isolation (developmental) residual than intimacy.

Nursing Interventions

The aim of MRM nursing interventions is to build trust, affirm and promote client strengths, promote positive orientation, facilitate perceived control, and set health-directed mutual goals. The first step in the process for this client is to collect self-care knowledge. This will help the nurse confirm, revise, and/or adapt nursing interpretations and impressions. Because the MRM nurse also approaches the interview process with unconditional acceptance and with a belief that all humans have the potential to grow, the nurse’s attitude will promote a sense of positive orientation in the client. (Note that this approach is used to facilitate the developmental stage of trust.) As an MRM nurse, you will want to explore your client’s perceived strengths and goals. It will also help you build a trusting, functional relationship with Debbie and help Debbie perceive a sense of control. (Note that this approach is used to facilitate the resolution of the developmental stage of autonomy.)

Remember that Debbie is impoverished. Thus she will not be able to project herself very far into the future. Perhaps the most that will be possible will be setting goals for increased physical comfort (basic physical needs) and a sense of being connected to you (belonging needs). By reinforcing her perceived strengths and helping her identify additional internal resources, she will continue to rework the tasks of trust and autonomy. She will also develop a sense of AI.

You can inform Debbie that we sometimes have life experiences that interfere with our ability to grow, that the miracle in life is that we always have new opportunities, and that it is never too late. Although it may seem that life is nothing but a cloudy storm, there usually is a rainbow if we can just learn how to find it. It might also be important to tell her that sometimes we do things to meet our needs. These actions seem right at the time but later we realize that they did not work very well. These actions make us neither bad nor wrong; they just alter our lives. It is never too late to start anew.

You can also ask Debbie what kind of information she would like to have. Tell her what information you can offer. (Start with survival needs and move up the hierarchy.) Let her choose whether she wants information and, if so, what information she wants. In this discussion you would probably offer to talk about how she could help herself be more comfortable or to quiet and calm her stomach if she receives chemotherapy or is feeling uncomfortable. It is important that we use language such as comfort—language that reflects health—rather than words that reflect illness, such as pain. You could also mention that when she is ready, you could teach her how to empty her bladder so she would be more comfortable.

To provide physical care it is essential that the approach include unconditional acceptance of the person and his or her body. Through soft voice tones, gentle and soothing touch, and eye contact, the nurse projects unconditional acceptance, love, and respect for the holistic person. Comments that identify physical strengths arealso important. Debbie needs to be assisted to discover what is right with her; with such discoveries she will be better able to handle her limitations.

Debbie also needs help with external resources. She has a social network, but she may not see them as her support system. Although the nurse will want to keep this in mind, Debbie probably will not want to talk about her family until she has developed new internal resources. Impoverished people have difficulty viewing the world from another person’s eyes. Instead, they often see the other as a part of their problems. However, Debbie will need help in planning if she has chemotherapy. Thus you might inform Debbie that you are there to talk and to help her problem solve and that Debbie should be encouraged to think about how she can meet her own needs when she is ready, but there is no rush. Right now the focus is on helping her rest and find comfort.

When Debbie indicates she is ready, she may need time to simply tell her story. Although we can only imagine that she has had a difficult childhood and marriage, only she can relate it in such a way as to express her real feelings. Informing her that all people deserve to be loved and respected but that it does not always happen is one way to initiate such a discussion.

Debbie will also want to discuss how she can care for her children and what will happen to them. To facilitate this discussion, you might comment about how beautiful her children are and how they are like their mother. When Debbie is ready and has built sufficient trust, she will raise the issue.

Remember that each of these topics is related to unmet needs, loss, and grief. Therefore, the nurse should expect to see behaviors that represent the grieving process, such as denial, shock, anger, bargaining, and sadness. Until Debbie has worked through the grieving process, you will not see acceptance with attachment to new objects or attachment to old objects in new ways. Do not be fooled by behaviors that suggest giving up; giving up is not the same as letting go. Giving up represents continued morbid grief (with unresolved losses); letting go represents moving on, attaching in new ways.

As Debbie continues to rework the tasks related to the first two stages of life, she will begin to work on initiative, followed by industry, identity, and intimacy. Throughout these processes it is important to help her begin to think about her life, what it has meant, and what her purpose in life might be. These processes are especially important for Debbie because she may be facing physical death. If that is the case, it is essential that she be given an opportunity to develop a sense of positive orientation, find meaning in life, and express her purpose for being. This will help her develop a sense of spiritual well-being.

Nursing Care of John with Modeling and Role-Modeling

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Description of Situation

John is friendly and interested in sharing his story. He seeks affiliation and hopes to find someone who will care for him and take care of him. His coping mechanisms (smoking and drinking) reflect oral stage one developmental processes with related unmet needs and developmental residual. His perception of his health status is congruent with that of his health care providers. He knows that he is physically compromised, that he drinks and smokes too much, that he has not followed his physician’s advice, and that this makes the doctors unhappy. He also recognizes that it would help his physical health if he quit smoking and drinking, but he expresses inability to give up these coping strategies at this time. This is because he does not have adequate developmental residual from the first two stages of life; he lacks drive, self-control, and willpower.

His living conditions facilitate some sense of AI, but it is not growth-directed. Although he lives alone in an apartment in a senior housing unit, his shortness of breath limits his daily activities. He is no longer able to bowl or carry out a number of activities that he enjoyed in the past. His recreational activities include visiting with other residents, smoking, and drinking. He recognizes that he is not eating enough but states that he lacks the interest or energy to cook.

John has experienced many losses in his life and probably has morbid grief with multiple related needs deficits. The changes that he has had to make, the activities that he has had to discontinue, and his inability to breathe without assistance and to complete his activities of daily living are all regular occurrences in his life. These have created perceived and real loss. He is also divorced, lives alone, and does not have children who visit regularly. Although his daughter lives 400 miles away, he commented that she probably would not visit him very often because ofhis drinking. He expressed feelings of sadness related to his divorce, his distant relationship with his daughter, and his inability to visit people outside of his residence because of his breathing problems.

Expectations

John does not envision significant changes occurring in his life situation. He believes that if there were people in his life who cared about him and were available when needed, his health situation would improve. He does not believe, however, that this is a realistic expectation. The nurse expects that caring for John would be easy while he was hospitalized and that he would leave as soon as he was stable. No other expectations for John were identified by the nurse or by the other health care providers. They no longer believed that John would be able to stop smoking or quit drinking.

Resources

When he was asked why he thought he had so many frequent hospitalizations, John talked about the lack of a social network and support system. His statement that he has a daughter who he rarely sees indicated his feelings of loneliness. He also stated, “I wish she was closer. I miss her. I don’t have any other family. My wife divorced me years ago because of my drinking.” In addition, he talked about visiting with the nurses who “cared” about him and took the time to visit with him as well as listen to his regrets about not visiting other people outside of his residence. In regard to John’s relationship with his physician, he perceived that he was frustrated with him and did not want to waste his time working with him. His feelings were corroborated by the physician.

John’s limited social network includes his friends with whom he smokes and drinks, the hospital staff he sees when he is admitted for hospitalization (the respiratory therapist greets him by his first name on admission and asks how he is doing), and his daughter. He does not seem to have a support system, but he communicates easily and openly with the nurse.

Goals and Life Tasks

His current goals include continuing to live independently and to experience minimal episodes of respiratory distress. His desired future goal would be to have a caring relationship with someone. The nurse’s goals for John include the following:

The physician would like John to be “compliant” with the medical plan. These goals are not compatible because John cannot stop smoking and drinking and is not motivated to eat better until he feels love, support, and connection to others.

Nursing Impressions

John has multiple survival, growth, and self-actualization needs deficits. He probably has a deficit motivation for relationships. This means that he has probablydeveloped relationships to meet his own needs without much consideration of the needs of the other member in the relationship, as is evidenced by the fact that he is divorced, his daughter is estranged, and his “friends” drink and smoke with him.

He lacks a sense of AI. Because of his strong need to be connected (affiliated) with someone who will care for him and because he has no such relationship, he has difficulty taking health-directed self-care actions. Instead, his actions are aimed at meeting his basic, oral needs. He cannot positively project himself into the future and has diminished internal and external resources; he is impoverished. John is at the age of generativity but is having difficulty projecting into the future. He has trouble with the task of initiative, which is most likely secondary to issues that deal with the tasks of trust and autonomy.

Thus John’s survival and growth needs deficits are related to early life experiences. He has unmet physical, safety and security, love and belonging, and self-esteem needs as well as unresolved losses. His psychosocial and physical subsystems interface in a way that jeopardizes his physical health.

Nursing Interventions

Because the aims of interventions are to build trust, promote positive orientation, gain a sense of control, affirm and build strengths, and set goals, initial interventions were designed to meet survival needs, facilitate secure attachment (related to developmental trust), and encourage autonomy following secure attachment. This would result in survival and growth needs satisfaction and would facilitate growth and new trust and autonomy residual.

To accomplish these outcomes, the nurse made weekly visits to John’s home for the first month. During these visits John and the nurse identified his strengths, reaffirmed his worth, and talked about his concerns, how he was feeling, and what would help him feel better. The nurse gave John a business card and told him that he could call whenever he wanted to talk with someone or needed help. She also called him about once a week to see how he was doing. During their phone calls and visits, John and the nurse also talked about generativity issues such as what his life had been about, what he had contributed, and what he could continue to contribute.

To help John continue to work on meeting his survival and growth needs (related to trust and autonomy), John was invited to join a support group that met every other week. The support group not only helped John build a support system but also provided him with people with whom he could connect. Group members were encouraged to discuss their feelings first and then to talk objectively about possible solutions to their problems. Then they were encouraged to think about the differences between their feelings and their thinking.

Finally, the nurse served as an advocate for John with the rest of the health care team and other agencies. She discussed his needs deficits, developmental processes, and relationships with the health care team. She also discussed the difference between compliance and adherence and the importance of facilitating adherence with clients like John. She explained that client adherence develops from goals set by clients, within the context of their world, rather than from expecting compliance based on goals set by others. Facilitating adherence is based on the assumption that all people want to grow, be the best they can be, and will grow when they haverepeated perceived needs satisfaction. Although this did not seem to change the team members’ goals, it did help alter their attitudes. They seemed more interested in John’s view of the world.

Summary

The nurse continued to see John for 2½ years. Shortly after she initiated the interventions, which were based on MRM, John quit smoking. He attended regular meetings and called the nurse regularly. He began to take his medication as prescribed and had no additional side effects. His hospitalizations decreased to once a year. Later, he quit drinking as well.

After about 2½ years, the nurse left the hospital. Later, the new nurse assigned to John decided that John was doing so well that he no longer needed to receive phone calls, attend the support group, or have special attention from the health care team. Within 6 months, he had an acute respiratory episode, was hospitalized, and died.