Theory of caring

Danuta M. Wojnar

“Caring is a nurturing way of relating to a valued other toward whom one feels a personal sense of commitment and responsibility”

(Swanson, 1991, p. 162).

Kristen M. Swanson

1953 to present

Credentials and background of the theorist

Kristen M. Swanson, RN, PhD, FAAN, was born in Providence, Rhode Island. She earned her baccalaureate degree (magna cum laude) from the University of Rhode Island, College of Nursing in 1975. She began her career as a registered nurse at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in Worcester, because the founding nursing administration clearly articulated a vision for professional nursing practice and actively worked with nurses to apply these ideals while working with clients (Swanson, 2001).

As a novice nurse, more than anything Swanson wanted to become a knowledgeable and technically skillful practitioner with a goal of teaching others. Hence, she pursued graduate studies in Adult Health and Illness Nursing at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. After receiving a master’s degree in nursing in 1978, she worked briefly as clinical instructor of medical-surgical nursing at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing and subsequently enrolled in the Ph.D. in nursing program at the University of Colorado in Denver. There she studied psychosocial nursing with an emphasis on the concepts of loss, stress, coping, interpersonal relationships, person and personhood, environments, and caring.

While a doctoral student, as part of a hands-on experience with a self-selected health promotion activity, Swanson participated in a cesarean birth support group focused on miscarriage. The guest speaker, a physician, focused on pathophysiology and health problems prevalent after miscarriage, but women attending the meeting were more interested in talking about their personal experiences with pregnancy loss. That day Swanson decided to learn more about the human experience and responses to miscarrying. Caring and miscarriage became the focus of her doctoral dissertation and subsequently her program of research.

Swanson received an individually awarded National Research Service postdoctoral fellowship from the National Center for Nursing Research, which she completed under the direction of Dr. Kathryn E. Barnard at the University of Washington in Seattle. She joined the faculty at the University of Washington School of Nursing and continued her scholarly work as professor and chairperson of the Department of Family Child Nursing until summer 2009. In addition to teaching and administrative responsibilities at the University of Washington, She conducted research funded by the National Institutes of Nursing Research; published, mentored faculty and students, and served as a consultant at national and international levels. She has been an invited speaker or visiting professor on multiple occasions, including Karolinska Institute in Sweden, IWK (Isaac Walton Killam) Health Centre, a tertiary care hospital for women, children, and families in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, and, most recently, the National Cheng Kung University in Taiwan, Taiwan. While at the University of Washington in 2009, Swanson also held the University of Washington Medical Center Term Professorship in Nursing Leadership.

In 2009, Swanson was appointed Dean and Alumni Distinguished Professor at the University of North Carolina (UNC) School of Nursing at Chapel Hill and Associate Chief Nursing Officer for Academic Affairs at UNC Hospitals. Dr. Swanson continues her scholarship, which in recent years shifted to translational research and consulting with various organizations to enact the Theory of Caring in clinical practice, education, and research. Her service contributions include service on the editorial board or reviewer for Journal of Nursing Scholarship, Nursing Outlook, Research in Nursing and Health,and the International Journal of Human Caring. In recognition of many outstanding contributions to the nursing discipline, among other honors, Swanson was inducted as a fellow in the American Academy of Nursing in 1991, received a Distinguished Alumnus Award from the University of Rhode Island in 2002, and was selected as a fellow for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Nurse Executive Fellows program in 2004.

Theoretical sources

Swanson has drawn on various theoretical sources while developing her Theory of Caring. She recalls that from the beginning of her nursing career, her education and clinical experience made her acutely aware of the profound difference caring made in the lives of people she served:

Watching patients move into a space of total dependency and come out the other side restored was like witnessing miracles unfold. Sitting with spouses in the waiting room while they entrusted the heart (and lives) of their partner to the surgical team was awe inspiring. It was encouraging to observe the inner reserves family members could call upon in order to hand over that which they could not control. It warmed my heart to be so privileged as to be invited into the spaces that patients and families created in order to endure their transitions through illness, recovery, and, in some instances, death

(Swanson, 2001, p. 412).

Swanson credits several nursing scholars for insights that shaped her beliefs about the nursing discipline and influenced her program of research. She acknowledges Dr. Jacqueline Fawcett’s course on the conceptual basis of nursing practice, which led her to understand the differences between the goals of nursing and other health disciplines, and to realize that caring for others as they go through life transitions of health, illness, healing, and dying was congruent with her personal values (Swanson, 2001). Swanson chose Dr. Jean Watson as mentor during her doctoral studies. She attributes the emphasis on exploring the concept of caring in her doctoral dissertation to Dr. Watson’s influence. However, despite the close working relationship and emphasis on caring in Swanson’s dissertation, Swanson’s program of research on caring and miscarriage is not an application of Watson’s Theory of Human Caring (Watson, 1979, 1988, 1999). Instead, both Swanson and Watson assert that compatibility of findings on caring in their individual programs of research adds credibility to their theoretical assertions (Swanson, 2001). Swanson acknowledges Dr. Kathryn E. Barnard for encouraging her transition from the interpretive to a contemporary empiricist paradigm and for transferring caring knowledge from her phenomenological investigations to intervention research and clinical practice with women who have miscarried.

Use of empirical evidence

Swanson formulated her Theory of Caring inductively, as a result of several investigations. For her doctoral dissertation, using descriptive phenomenology, she analyzed data from in-depth interviews with 20 women who had recently miscarried. As a result of this phenomenological investigation, Swanson proposed two models: (1) The Caring Model, and (2) The Human Experience of Miscarriage Model. The Caring Model proposed five basic processes (knowing, being with, doing for, enabling, and maintaining belief) that give meaning to acts labeled as caring (Swanson-Kauffman, 1985, 1986, 1988a, 1988b). This was foundational for Swanson’s (1991) middle-range Theory of Caring.

While a postdoctoral fellow, Swanson conducted a phenomenological study, exploring what it was like to be a provider of care to vulnerable infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Swanson (1990) discovered that the caring processes she identified with women who miscarried were also applicable to mothers, fathers, physicians, and nurses who were responsible for care of infants in the NICU. Hence, she retained the wording that described the acts of caring and proposed that all-inclusive care in a complex environment embraces balance among caring (for the self and the one cared for), attaching (to others and roles), managing responsibilities (assigned by self, others, and society), and avoiding bad outcomes (Swanson, 1990).

In a subsequent phenomenological investigation conducted with socially at-risk mothers, Swanson (1991) explored what it had been like for these mothers to receive an intense, long-term nursing intervention. Swanson recalls that after this study she was finally able to define caring and refine the understanding of caring processes. Collectively, phenomenological inquiries with women who miscarried, caregivers in the NICU, and socially at-risk mothers formed a basis for expansion of the Caring Model into the middle-range Theory of Caring (Swanson, 1991, 1993).

Swanson tested her Theory of Caring with women who miscarried in investigations funded by the National Institutes of Nursing Research and other funding sources. Swanson’s (1999a, 1999b) intervention research (N = 242) examined the effects of caring-based counseling sessions on women coming to terms with loss and emotional well-being during the first year after miscarrying. Additional aims were examination of the effects of passage of time on healing during that first year and development of strategies to monitor caring interventions. This study established that passing of time had positive effects on women’s healing after miscarriage, however, caring interventions had a positive impact on decreasing the overall disturbed mood, anger, and level of depression. The second aim was to monitor the caring variable and determine if caring was delivered as intended. To do so, caring was monitored in the following three ways:

1. Approximately 10% of counseling sessions were transcribed and data were analyzed using inductive and deductive content analysis.

2. Before each caring session, the counselor completed McNair, Lorr, and Droppleman’s (1981) Profile of Mood States to monitor whether the counselor’s mood was associated with women’s ratings of caring after each session, using an investigator-developed Caring Professional Scale.

3. After each session, the counselor completed an investigator-developed Counselor Rating Scale and took narrative notes about her own counseling.

The most noteworthy finding of monitoring caring was that clients were highly satisfied with caring received during counseling sessions, suggesting caring was delivered and received as intended.

Swanson’s (1999c) subsequent investigation was a literary metaanalysis on caring. An in-depth review of 130 investigations on caring led Swanson to propose that knowledge about caring may be categorized into five hierarchical domains (levels), and research conducted in any one domain assumes the presence of all previous domains (Swanson, 1999c).

• The first domain refers to the persons’ capacities to deliver caring.

• The second domain refers to individuals’ concerns and commitments that lead to caring actions.

• The third domain refers to the conditions (nurse, client, organizational) that enhance or diminish the likelihood of delivering caring.

• The fourth domain refers to actions of caring.

• The fifth domain refers to the consequences or the intentional and unintentional outcomes of caring for both the client and the provider (Swanson, 1999c).

Conducting the literary metaanalysis clarified the meaning of the concept of caring as it is used in the nursing discipline and validated the transferability of Swanson’s middle-range Theory of Caring beyond perinatal context.

Subsequently, Swanson authored or coauthored numerous scholarly articles and book chapters on application of caring-healing relationships in clinical practice and education or tested the theory of caring. Swanson coauthored an article on nursing’s historical legacy as a caring—healing profession, and the meaning, significance, and consequences of optimal healing environments for modern nursing practice, education, and research (Swanson & Wojnar, 2004).

The article presented the core foci of nursing as a discipline: what it means to be a person and experience personhood; the meaning of health at the individual, family, and societal levels; how environments create or diminish the potential for the promotion, maintenance, or restoration of well-being; and the caring-healing therapeutics of nursing. A book chapter followed toenhance nurses’ capacity for compassionate caring (Swanson, 2007). In it, Swanson explored how caring matters to well-being of every person and described conditions that impact quality of nurse caring ranging from the interpersonal relationships through physical environments, to executive/managerial leadership. Swanson’s coauthored works focused on social and economic factors that affect nursing shortage and quality of care (Grant & Swanson, 2006) and consumer satisfaction with health care (Mowinski-Jennings, Heiner, Loan, et al., 2005). Swanson and colleagues also explored complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) attitudes and competencies of nursing students and faculty and the results of integrating CAM into the nursing curriculum as a holistic approach to nursing (Booth-Laforce, Scott, Heitkemper, et al., 2010).

In her own program of research, Swanson tested the usability of the Theory of Caring. In 2003, Swanson and colleagues published results from an investigation on the miscarriage effects on interpersonal and sexual relationships during the first year after loss from women’s perspective and investigated the context and evolution of women’s responses to miscarriage during the first year after loss (Swanson, Connor, Jolley, et al., 2007). In 2009, Swanson and her research team published results of a funded intervention study called Couples Miscarriage Healing Project. The purpose was to better understand the effects of miscarriage on men and women as individuals and as couples, to explore the effects of miscarriage on couple relationships, and to identify best ways of helping men and women heal as individuals and as couples after unexpected pregnancy loss. Study participants (341 heterosexual couples) were randomly assigned to control or one of the following three treatment groups: (1) nurse caring, which entailed attending three counseling sessions with a nurse, (2) self-caring, which involved completing three videos and workbooks, or (3) combined caring, which involved attending one nurse caring session and completion of three videos and workbooks, to determine the most effective way of supporting couples after miscarriage. Interventions, based on Swanson’s Theory of Caring and Meaning of Miscarriage Model, were offered at 1, 5, and 11 weeks after enrollment. Outcomes included depression (CES-D) and grief, pure grief (PG), and grief-related emotions (GRE). Differences in rates of recovery were estimated via multilevel modeling conducted in a Bayesian framework. Bayesian odds (BO) ranging from 3.0 to 7.9 showed that nurse caring was most effective for accelerating women’s resolution of depression. BO of 3.2 to 6.6 favored nurse caring intervention and no treatment over self, and combined caring for resolving men’s depression. BO of 3.1 to 7.0 favored all three interventions over no treatment for accelerating women’s grief resolution, and BO of 18.7 to 22.6 favored nurse caring and combined caring over self-caring or no treatment for resolving men’s grief. BO ranging from 2.4 to 6.1 favored nurse-caring and self caring over combined caring or no treatment for promoting women’s resolution of grief-related emotions. BO from 3.5 to 17.9 favored nurse caring, combined caring, and control over self-caring for resolving men’s grief emotions. Nurse-caring had the overall most positive impact on couples’ resolution of grief and depression. In addition, grief resolution was accelerated by self-caring for women and combined caring intervention for men. Researchers concluded that applying the Theory of Caring in clinical practice is an effective strategy to promote healing after unexpected pregnancy loss for women and men as individuals and as couples.

Swanson continues to contribute to research of other scholars. In 2006, Wojnar and Swanson explored why lesbian mothers should deserve special consideration when it comes to healing after miscarriage. As a result, Wojnar, Swanson, and Adolfsson (2011) offered a revised conceptual model of miscarriage inclusive of lesbian population for clinical practice and research. Swanson coauthored findings from an investigation that explored soldiers’ experiences with military health care (Jennings, Loan, Heiner, et al., 2005). Findings suggest that quality of care for soldiers is improved by narrowing the gap between what is offered for them as consumers and what they experience when they seek care. Most recently, Swanson coauthored results from a study that explored the experiences of parents following moderate to severe traumatic brain injury of their child (Roscigno & Swanson, 2011) as well as the quality of life for children following traumatic brain injury (Roscigno, Swanson, Solchany, et al., 2011), where participants described health and cultural barriers leading to misunderstandings that could be easily avoided.

Swanson’s Theory of Caring has been validated for a wide range of usage in research, education, and clinical practice.

Major assumptions

In 1993, Swanson further developed her theory of informed caring by making her major assumptions explicit about the four main phenomena of concern to the nursing discipline: nursing, person/client, health, and environment.

Nursing

Swanson (1991, 1993) defines nursing as informed caring for the well-being of others. She asserts that the nursing discipline is informed by empirical knowledge from nursing and other related disciplines, as well as “ethical, personal and aesthetic knowledge derived from the humanities, clinical experience, and personal and societal values and expectations” (Swanson, 1993, p. 352).

Person

Swanson (1993) defines persons as “unique beings who are in the midst of becoming and whose wholeness is made manifest in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors” (p. 352). She posits that the life experiences of each individual are influenced by a complex interplay of “a genetic heritage, spiritual endowment and the capacity to exercise free will” (Swanson, 1993, p. 352). Hence, persons both shape and are shaped by the environment in which they live.

Swanson (1993) views persons as dynamic, growing, self-reflecting, yearning to be connected with others, and spiritual beings. She suggests the following: “.... spiritual endowment connects each being to an eternal and universal source of goodness, mystery, life, creativity, and serenity. The spiritual endowment may be a soul, higher power/Holy Spirit, positive energy, or, simply grace. Free will equates with choice and the capacity to decide how to act when confronted with a range of possibilities” (p. 352). Swanson (1993) noted, however, that limitations set by race, class, gender, or access to care might prevent individuals from exercising free will. Hence, acknowledging free will mandates nursing discipline to honor individuality and consider a whole range of possibilities that are acceptable or desirable to those whom the nurses attend.

Moreover, Swanson posits that the other, whose personhood nursing discipline serves, refers to families, groups, and societies. Thus, with this understanding of personhood, nurses are mandated to take on leadership roles in fighting for human rights, equal access to health care, and other humanitarian causes. Lastly, when nurses think about the other to whom they direct their caring, they also need to think of self and other nurses and their care as that cared-for other.

Health

According to Swanson (1993), to experience health and well-being is:

“.... to live the subjective, meaning-filled experience of wholeness. Wholeness involves a sense of integration and becoming wherein all facets of being are free to be expressed. The facets of being include the many selves that make us a human: our spirituality, thoughts, feelings, intelligence, creativity, relatedness, femininity, masculinity, and sexuality, to name just a few” (p. 353).

Thus, Swanson sees reestablishing well-being as a complex process of curing and healing that includes “releasing inner pain, establishing new meanings, restoring integration, and emerging into a sense of renewed wholeness” (Swanson, 1993, p. 353).

Environment

Swanson (1993) defines environment by situation. She maintains that for nursing it is “any context that influences or is influenced by the designated client” (p. 353). Swanson states that there are many kinds of influences on environment, such as the cultural, social, biophysical, political, and economic realms, to name only a few. According to Swanson (1993), the terms environment and person-client in nursing may be viewed interchangeably. For example, Swanson posits, “for heuristic purposes the lens on environment/designated client may be specified to the intra-individual level, wherein the ‘client’ may be at the cellular level and the environment may be the organs, tissues or body of which the cell is a component” (p. 353). Therefore, what is considered an environment in one situation may be considered a client in another.

Theoretical assertions

Swanson’s Theory of Caring (Swanson, 1991, 1993, 1999b) was empirically derived through phenomenological inquiry. It offers a clear explanation of what it means for nurses to practice in a caring manner and emphasizes that the goal of nursing is promotion of well-being. Swanson (1991) defines caring as “a nurturing way of relating to a valued other toward whom one feels a personal sense of commitment and responsibility” (p. 162).

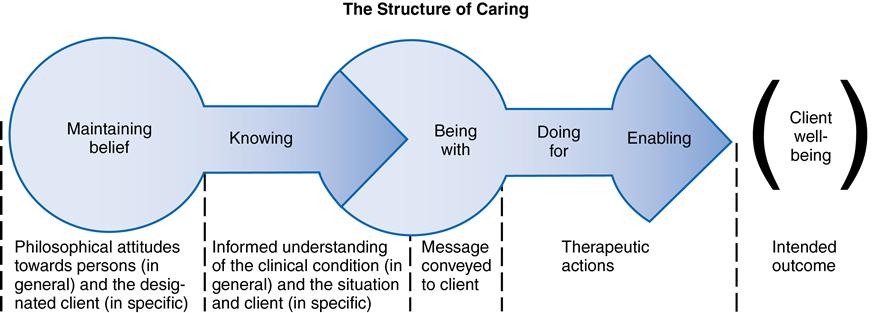

According to Swanson, a fundamental and universal component of good nursing is caring for the client’s biopsychosocial and spiritual well-being. Swanson (1993) asserts that caring is grounded in maintenance of a basic belief in human beings, supported by knowing the client’s reality, conveyed by being emotionally and physically present, and enacted by doing for and enabling the client. The caring processes overlap and may not exist in separation. Each is an integral component of the overarching structure of caring (Figure 35–1). Swanson (1993) has noted that the repertoire of caring therapeutics of novice nurses might be limited and restricted by inexperience. Conversely, the techniques and knowledge imbedded in caring of experienced nurses are elaborate and subtle, so caring might go unnoticed by an uninformed observer. Yet, Swanson (1993) asserts that, regardless of the years of nursing experience, caring is delivered as a set of sequential processes (subconcepts) created by the nurse’s own philosophical attitude (maintaining belief), understanding (knowing), verbal and nonverbal messages conveyed to the client (being with), therapeutic actions (doing for and enabling), and the consequences of caring (intended client outcome).

Logical form

Swanson’s middle-range Theory of Caring was developed empirically using an inductive approach. Chinn and Kramer (2011) note, “With induction people induce hypotheses and relationships by observing or experiencing an empiric reality and reaching some conclusion” (p. 182). Swanson’s theory was generated from phenomenological investigations with women who experienced unexpected pregnancy loss, caregivers of premature and ill babies in the newborn intensive care unit (NICU), and socially at-risk mothers who received long-term care from master’s-prepared nurses. Swanson claims that her in-depth meta-analysis of research on caring has supported the generality of her theory beyond a perinatal context (Swanson, 1999c).

Acceptance by the nursing community

Practice

The usefulness of Swanson’s Theory of Caring has been demonstrated in research, education, and clinical practice. The proposition that caring is central to nursing practice had its beginning in the theorist’s own insights into the importance of caring in professional nursing practice and in findings from Swanson’s phenomenological investigations. Her subsequent investigations demonstrated applicability of the Theory of Caring in clinical nursing practice, education, and research. Swanson’s theory has been embraced as a framework for professional nursing practice in the United States, Canada, and Sweden. An example is the Dalhousie University School of Nursing in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, which selected Swanson’s Theory of Caring to guide the development of future generations of nurses as caring professionals. Likewise, nurses at IWK (Isaac Walton Killam) Health Centre, a tertiary care hospital for women, children, and families in Halifax, Nova Scotia, have recognized the traditional legacy of nursing as a caring-healing discipline and the concepts in Swanson’s theory as applicable in practice. Since 1998, the Nursing Practice Council at IWK used Swanson’s Theory of Caring as their framework for professional nursing practice.

Nurse caring is manifested in different ways and practice contexts. For example, in a postpartum context, demonstration of a baby bath to new parents incorporates all five caring processes. The act involves being with by demonstrating bathing the newborn to the parents. The unrushed timing of the bath so the infant is awake and parents are present conveys willingness (doing for or enabling); and the observing, querying, and involving parents in the task engages them in their own infant’s care (intended outcome) while acknowledging that they are perfectly capable of caring for their new child and that their preferences matter (knowing and maintaining belief). In carrying out this seemingly simple act, the nurse creates an optimal environment for learning that enables new parents to make decisions about infant care, while leveraging the task as an opportunity to engage in a meaningful social encounter and developing a trusting relationship.

Education

Humane and altruistic caring occurs when the theory is used in various practice areas such as feeding or grooming an incapacitated older adult, monitoring and managing the recovery of a patient who suffered a stroke, or enhancing infant care skills of new parents. Nurse caring, as demonstrated by Swanson in research with women who miscarried, caregivers in the NICU, and socially at-risk mothers, recognizes the importance for nurses to attend to the wholeness of humans in their everyday lives. Thus Swanson’s theory offers nurse educators a simple way of initiating students into the profession by immersing them in the language of what it means to be caring and cared for in order to promote, restore, or maintain the optimal wellness of individuals.

Research

Swanson has persisted in the development of her theory, describing and defining the concept of caring and basic caring processes, instrument development, and testing in intervention research with women and men who have experienced unexpected pregnancy loss. Recent review of computerized databases (MEDLINE, CINHAL, and Digital Dissertations) indicated that Swanson’s work on caring and miscarriage has been cited or otherwise utilized in over 160 data-based publications. Examples of applications of Swanson’s Theory of Caring in clinical research include exploring clinical scholarship in practice (Kish & Holder, 1996); guidelines for nurses working with patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (Yorkston, Klasner, & Swanson, 2001); assessing the impact of caring in work with vulnerable populations (Kavanaugh, Moro, Savage, et al., 2006); the importance of creating a caring environment for older adults (Sikma, 2006); Wojnar’s (2007) study of lesbian couples who miscarried; and Roscigno’s research of children who sustained traumatic brain injury (Roscigno & Swanson, 2011; Roscigno, Swanson, Solchany, et al., 2011).

Further development

Swanson is interested in further development by testing and applying her theory in clinical practice. There is much potential for further development by testing Swanson’s Theory of Caring in various contexts of health and illness. Also, her processes of caring suggest that the theory is applicable in other helping disciplines such as teaching, social work, and medicine as well as other life situations for nursing.

Critique

Clarity

The concept of caring and caring processes (knowing, being with, doing for, enabling, and maintaining belief) that are central to the theory are clearly defined and arranged in a logical sequence that describes the processes of caring delivery. Swanson’s theory offers clear definitions and contextual linkages with the concepts of the nursing discipline (person, nurse, environment, and health) in nurse-client interactions, thus further explicating the definitions.

Simplicity

A simple theory has a minimal number of concepts. Swanson’s Theory of Caring is simple yet elegant. It brings the importance of caring to the forefront and exemplifies the discipline’s values. The main purpose of the theory is to foster delivery of nursing care focused on the needs of the individuals while fostering their dignity, respect, and empowerment. Simplicity and consistent language used to define the concepts and processes allows students and nurses to understand and apply Swanson’s theory in their practice.

Generality

Swanson’s Theory of Caring may be applied in research and clinical work with diverse populations. The conditions essential for delivering caring that promotes individuals’ wholeness across the life span have been described clearly (Swanson, 1999c). Hence, the theory is generalizable to nurse-client relationships in many clinical settings.

Accessibility

Swanson’s Theory of Caring concepts and assumptions are grounded in clinical nursing practice and research using an empirical approach. The completeness and simplicity of operational definitions strengthen empirical precision of this theory. Swanson and others have successfully applied her theory in numerous studies. Swanson and her research team tested the Theory of Caring in a clinical trial with women and men who experienced miscarriage and demonstrated that caring intervention resulted in decreased depressive mood and facilitated healthy grieving for both genders. Swanson has published research guidelines with colleagues for assessing the impact of caring healing relationships in clinical nursing (Quinn, Smith, Ritenbaugh, et al., 2003) and developed self-report instruments to measure caring as delivered by health care professionals and by couples to each other (Swanson, 2002). The template for delivering caring-based interventions and the research-based instruments open possibilities for use and further testing with other populations.

Importance

Swanson’s Theory of Caring describes nurse-client relationships that promote wholeness and healing. The theory offers a framework for enhancing contemporary nursing practice, education, and research while bringing the discipline to its traditional values and caring-healing roots. Swanson’s Theory of Caring has been applied to interdisciplinary caring relationships beyond nurse-client encounters. Recent applications in clinical nursing practice show tangible positive results. For example, since coming to the UNC School of Nursing at Chapel Hill as Dean, Swanson has focused on intensifying the linkages among nursing education, research, and practice. In partnership with Clinical Professor Dr. Mary Tonges, Chief Nursing Officer and Senior Vice President for Patient Care Services at UNC Hospital, Swanson has worked on strengthening the scholarship that supports nursing practice and enhances the relevance of nursing education and research to clinical practice through quality improvement projects. This research partnership has already resulted in positive outcomes on nursing workplace satisfaction and patient safety. Likewise, Swanson’s Theory of Caring has been applied in clinical practice and evaluated on selected variables at Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle, Washington, resulting in positive outcomes for patients and nurses.

Critical thinking activities

1. Consider Swanson’s Theory of Caring as a framework for your own nursing practice and research. How is it applicable?

2. Think about a time when you felt that someone cared about you deeply. Remember what it felt like to experience caring. Now reflect on that experience and review your experience in the context of the processes of caring in Swanson’s theory.

3. Think about an interaction with a client-family in your clinical practice that you wish you could change or improve. Use the processes of the Theory of Caring to critically assess about where you might have made more appropriate actions. If it were possible to improve this interaction, what would you change and why?

Points for further study

■ Swanson, K. M. (1998). Caring made visible. Creative Nursing, 4(4), 8–11, 16.

■ Swanson, K. M. (1999a). Research-based practice with women who have had miscarriages. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 31(4), 339–345.

■ Swanson, K. M. (1999b). The effects of caring, measurement, and time on miscarriage impact and women’s well-being in the first year subsequent to loss. Nursing Research, 48(6), 288–298.

■ Swanson, K. M. (1999c). What’s known about caring in nursing: A literary meta-analysis. In A. S. Hinshaw, J. Shaver, & S. Feetham (Eds.), Handbook of clinical nursing research (pp. 31–60). Thousand Oaks, (CA): Sage.

■ Swanson, K. M., & Wojnar, D. (2004). Optimal healing environments in nursing. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 10(1), 43–48.

■ Swanson, K. M., Chen, H. T., Graham, J. C., Wojnar, D. M., & Petras, A. (2009). Resolution of depression and grief during the first year after miscarriage: A randomized controlled clinical trial of couples-focused interventions. Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-based Medicine, 18(8), 1245–1257.