CHAPTER 12 PLANNING FOR COMMUNITY DENTAL PROGRAMS

Microbiologist Rene Dubos has suggested that most of human history has been a result of accidents and blind choices.1 When a crisis occurs, our solutions are immediate and involve piecemeal efforts rather than considered and thoughtful planning. The need to develop our ability to predict, plan, and thus prevent the same crisis from recurring should have the highest priority.

WHY PLAN?

As part of our role as health professionals, we are called on to assist health agencies and organizations in developing plans for obtaining dental care. We need to develop our own abilities to take our dental expertise and channel it into the areas of policy development, decision making, and program planning in a system more complex than the one with which we are familiar in the private dental office. This complex system may take the form of a community, an organization, a corporation, or an institution. The system can be better understood if we look on it as a patient, possessing certain needs and characteristics. Because we are dealing with more than one individual, planning a program for a community or institution requires a deep understanding and analysis of the system as a whole and of the individual members that make up the system.

Planning Dental Care for the Patient

The steps the dentist takes when seeing a patient for the first time can be compared with the steps a planner takes when viewing a system for the first time. A new patient who walks into the dental office is given a medical and dental history form to complete. This record provides background information on the patient’s health, history of diseases, and drug reactions, as well as the patient’s history of dental care. Information on the patient’s ethnic background, degree of education, and financial status may indicate the patient’s attitude about dental care, the type of dental care wanted, and how that care will be financed. A clinical examination with the use of radiographs further reveals the type and quality of dental care received and identifies any existing conditions or disease requiring treatment. For the dentist these steps assess the needs of the patient.

The next step is to identify and diagnose the problem or problems. Perhaps the patient requires full mouth reconstruction to restore the mouth to optimum functioning. The dentist reviews with the patient the ideal plan and acceptable alternatives based on the patient’s wants and financial limitations. Once the patient accepts the treatment plan and the method of payment, the plan is ready to be implemented.

The dentist selects the appropriate person to perform the necessary services from a staff of specialists and designs a realistic timetable to coordinate who will do what first, second, and so on until treatment has been completed.

When treatment has been completed, the patient is placed on an appropriate recall schedule and returns to have an evaluation of the care that was rendered. Any modifications or adjustments are done at this time. The patient is then placed on a maintenance plan and returns periodically for a routine examination. This becomes an ongoing process for the patient and the dentist. The difference between the planning steps for an individual patient and the planning steps for a community is that dealing with more than one individual at a time requires more complex steps. Box 12-1 compares the provision of dental care for a private patient with that for a community.

BOX 12-1 A Comparison of the Provision of Dental Care for a Private Patient and a Community

Modified from Young W, Striffier D: The dentist, his practice, and the community, Philadelphia, 1969, WB Saunders.

Private Patient

Community

Planning Dental Care for the Community

Usually a planner is contacted because a problem has been identified within the community, for example, a high incidence of early childhood caries (ECC) among children. The planner, like the dentist, begins by conducting a needs assessment of the affected children and their families. Included in the needs assessment are the population’s health problems and beliefs, ethnic makeup, diet, education and socioeconomic status, number of children with ECC, and the severity of the disease.2 Again, this information will help the planner in determining an appropriate plan.

Once the information has been gathered and analyzed, the planner, along with the community, sets priorities for dealing with the problem. The planner may decide that the first priority is to treat all existing cases of nursing bottle caries within the community, followed by reeducating the parents of these children and those individuals who recommended sweetening the contents of the children’s bottles. The planner then sets a reasonable goal to reduce the incidence of ECC within that community within a specified time and proposes methods or objectives to accomplish the goal.

Next, the planner identifies resources available to the community, such as who will provide the treatment, how the care will be financed, and where the care will be provided. If constraints exist (e.g., no transportation available to bring the children to the dental office or a lack of funds necessary to provide the treatment), the planner needs to consider alternative strategies to accomplish the intended goal. The planner might identify and recruit volunteer dentists or dental students to treat the children at no cost to the community.

Once the decision is made and approved by the community, it is ready for implementation. An implementation timetable is developed to provide a schedule for putting the plan into action.

After the children have been treated, a 6-month follow-up examination is instituted to evaluate the effectiveness of the plan. At that time the planner addresses questions such as the following: How many children identified as having ECC were treated? How many dropped out of treatment, and why? How many developed new ECC? The answers to these questions will help the planner to modify and adjust the program according to the needs of the community.3

Many kinds of planners exist. Some have been professionally trained or educated, whereas others have received on-the-job experience within their organization. There are two distinct approaches to planning: internal, planning by individuals within the system or organization; and external, planning by those brought in from outside.4 A planner hired from within the system is usually an individual whose work responsibility is to plan for the system on a full-time basis. The advantage of hiring from within is that the planner already has a true understanding of the issues and operation of the system, including the subtleties of that system. This knowledge enables the planner to begin making decisions more quickly regarding appropriate action. The disadvantage, however, is that the planner may already have acquired certain biases about the system that could influence his or her objectivity.

The planner brought in from outside is usually an individual who contracts to work for the company or agency on a consulting basis for a short period. The planner’s job is to assist the organization in its planning by formulating a new proposal or making recommendations for changing an existing plan. The advantage of an outside planner is that the organization may receive a fresher outlook, less bias, and a greater sense of objectivity. The drawback is that the outside planner requires more time to reach a sufficient level of understanding for effective action to take place.

One of the most important concerns for any planner is to take into consideration the human element. Statistics alone do not tell the whole story. For example, a planner who reviews the health labor statistics on a multiethnic community and who sees that, overall, sufficient numbers of practitioners work within the community may think that the community does not need any new practitioners. A closer examination of the practitioner and patient populations may reveal that the practitioners are primarily of a certain ethnic background and do not like treating patients of different ethnic backgrounds, of which there are a great number in the community. Thus large subgroups of the population may not have access to dental care, even though statistically enough dentists are available in the community.5 Although statistics can be most useful in analyzing data, a planner must be aware of their limitations.

PLANNING: A DEFINITION

Banfield presents a basic definition of the term planning: “A plan is a decision about a course of action.”6 In other words, a plan is a systematic approach to defining the problem, setting priorities, developing specific goals and objectives, and determining alternative strategies and a method of implementation.

Many types of health planning exist. Each varies according to the factors affecting the health system, such as the geography of a region, the sociocultural background of the population, economic considerations, and the political situation. Some types of health planning, as outlined by Spiegel and associates,7 include the following:

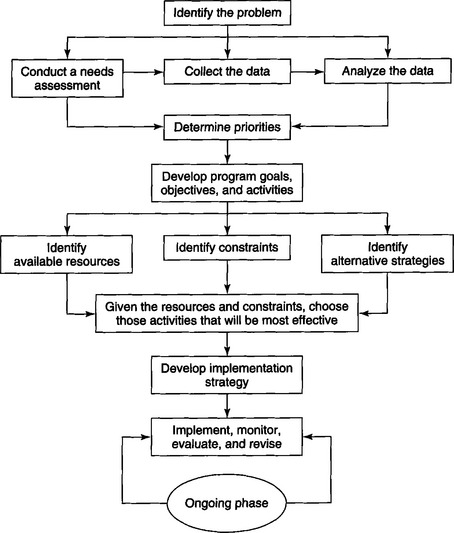

This chapter describes various types of health planning but concentrates specifically on the program-planning process. This process of program planning uses a systematic approach, as seen in Fig. 12-1, and should be used as a guide to solving a particular problem. The process can be compared with the ability of a jazz musician to take the notes of a standard musical scale and use them to create a unique melody. In a similar fashion, a planner uses the program-planning steps to create a plan that is unique for the specific situation or system. The process of planning is dynamic. Within a fluctuating and ever-changing system, the process itself must remain fluid and flexible, responsive to the presentation of new factors and issues. This chapter discusses the components of program planning and focuses on the various options available to the planner. The initial step in the planning process is to conduct a needs assessment.

There are several reasons why a planner should conduct a needs assessment. The primary reason is to define the problem and to identify its extent and severity. Second, the assessment is used to obtain a profile of the community to ascertain the causes of the problem. This information helps in developing the appropriate goals and objectives in the problem solution. Assessing the community’s needs not only involves identifying existing health problems but also potential health problems and health promotion needs.8

A needs assessment evaluates the effectiveness of the program. This is accomplished by obtaining baseline information and, over time, measuring the amount of progress achieved in solving the specific problem.

Suppose the planner designed a program to administer fluoride tablets to all school-age children in a given community. To determine how effective a fluoride tablet program is in terms of reduction of dental caries, the planner would first establish a baseline needs assessment of the caries rate among the school children. After the initial assessment, the program is implemented. To measure the effectiveness of such a preventive regimen, the planner would then make periodic assessments of the schoolchildren at various time intervals and compare these results with the initial assessment.

Conducting a needs assessment for a community can be a costly endeavor. If the funds are not readily available, the planner has several options. One option is to coordinate with the research activities of other agencies interested in obtaining similar health information on the given population. For example, a neighborhood health center may be involved in conducting a health survey of all the residents living in a defined geographic area.

Another method is to investigate surveys that have been done in the past by other organizations. Frequently, dental surveys are conducted through research departments of dental schools or through local and state health departments. If no surveys have ever been done, the planner may either want to solicit the assistance of these agencies and organizations or inform them that a survey will be conducted. This approach prevents overlap or duplication of activities.

Whether the planner conducts his or her own survey, combines efforts with others, or uses information from past surveys, it is important to consider what type of information is needed and how it should be obtained. Data can be obtained by various techniques such as survey questionnaires or clinical examinations or more informally through personal communications. The technique used is based on the population to be examined. Factors the planner should consider are the number of individuals, the extent and degree of severity of the problem, and the attitudes of the individuals to be surveyed. The greater the number of individuals to be examined, the more formal the survey. If the problem is clinical, as opposed to attitudinal, a clinical examination might be recommended. If the planner wants to interview a small group of individuals on their attitudes and feelings about a particular issue, a personal communication might be more appropriate.

To gather general information on a population, a population profile should be obtained. Such a profile includes the following:

To gather epidemiologic data on the patterns and distribution of dental disease, the planner can use a clinical examination, review patients’ dental records, or consult the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III) for data on a population residing in a similar geographic region with similar characteristics.

In addition to assessing the incidence and the distribution of dental disease, the planner needs to inquire into the history and current status of dental programs in the community. Questions to ask include the following:

The planner must learn how policies are developed and how decisions are made within the community. The following areas should be explored:

The planner needs to examine the types of resources available to the community. These include the funds, the facilities, and the labor. The following questions might be asked:

When planning a preventive dental program for a community or institution, it is important for the planner to determine where the population obtains water and the fluoride status of that water. In certain regions of the country, particularly in rural areas, many persons obtain their water from either individual wells or nearby rivers, lakes, or streams. The concentration of fluoride in the water may indicate that a fluoride supplement program is not necessary for that community. If drinking water emanates from several wells, the planner needs to obtain a fluoride concentration report on each.

If a community is obtaining water from a central area, the planner needs the following information:

To prevent duplication of fluoride administration, the planner also should inquire into the type of fluoride being administered to individuals in private offices, the schools, and the health centers. The following questions apply:

All the information presented in this section can be obtained easily through the various survey instruments discussed. If, however, a survey cannot be conducted, the necessary information about an institution or a community also can be obtained through other means. This approach requires the planner to investigate all available sources that might have data relevant to the population or the community. Such sources include the local, state, and federal agencies and private organizations.

In a small community one can find a tremendous amount of information on the community’s residents by visiting the local health department. The local health department maintains statistics on the population’s health status, morbidity and mortality, general health problems, and health service use. A trip to the chamber of commerce and town hall can provide useful information on the community profile, including population distribution, age breakdown, income, educational levels, school systems, and transportation. In a larger community the state health department can also provide health-related information for all communities, cities, and towns within the state.

The federal government has large volumes of health statistics data from many of its agencies. The most familiar and widely used sources of data are the National Health Surveys and the U.S. Census Bureau. These sources provide longitudinal and comparative data regarding large population groups. Because of the magnitude of the data gathering, these surveys are usually conducted once every 10 years. Consideration of the publication date of such data and its relevancy and applicability to specific populations is important.

Other sources for obtaining such data are research studies and investigative reports. Many of these studies are funded by government agencies and are conducted by academic health centers, local organizations, research companies, or consulting groups. A considerable volume of data is usually generated from their reports. A computer literature search, such as MEDLINE, may be helpful. The National Library of Medicine provides these computer searches for a nominal fee. Most medical libraries affiliated with universities also provide this service.

Once the data are obtained, the information must be analyzed before it can be put into a plan of action. The data presented in the following case study can be used to consider ways of developing an appropriate program.

Analysis of Data: A Case Study

BACKGROUND

Tide Water is the fifth largest city in Massachusetts. It is situated in the southeastern section of the state on the shore of Deep Water Bay. Excellent water resources and deep-water shipping potential brought industrial growth to Tide Water, and it became the “spindle city of the world” as the cotton industry flourished. Native granite was used to construct multistory factories, some of which are still in use. This prosperity ended quickly when the cotton manufacturers moved to the South in the 1930s and 1940s. The problem of vacant mill space, in addition to the Depression, made Tide Water’s economic situation one of the worst in the country. Tide Water was able to make a strong recovery with a growing garment industry, which replaced the cotton mills and other manufacturers and provided a more diversified industrial base. The available information about Tide Water is listed in the following sections.

ETHNIC AND RACIAL CHARACTERISTICS

Figures reflect a large immigrant population, principally Portuguese

AGE DISTRIBUTION

| Total Male | Total Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Under 5 | 4,223 | 4,047 |

| 5-14 | 8,120 | 7,893 |

| 15-19 | 378 | 24,028 |

| 20-64 | 23,992 | 27,458 |

| Over 64 | 4,902 | 8,453 |

EDUCATION

Median number of school years completed: 8.8

PERSONAL INCOME

| Salary | Families |

|---|---|

| Less than $5,000 | 616 |

| $5,000–$9,999 | 2,341 |

| $10,000–$13,999 | 2,988 |

| $14,000–$19,999 | 3,922 |

| $20,000–$24,999 | 4,474 |

| $25,000–$34,999 | 5,761 |

| $35,000–$49,999 | 2,838 |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 2,079 |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 407 |

| $100,000 or more | 220 |

| Total families | 25,646 |

| Median income | $18,000 |

TRANSPORTATION

Bus service: intracity and intercity

Taxi service: three companies, with a total of 65 radio-equipped cabs

Highways and streets: four major highways (2 north-south, 2 east-west), 600 miles of streets, 99% paved

FACILITIES

Two hospitals (725-bed capacity)

One community health center (diagnosis, primary dental health care, education, and prevention; sliding fee)

Mental health centers (many facilities, inpatient and outpatient clinics, and residencies; free and sliding-scale fee)

AIDS, venereal disease, and tuberculosis programs (free)

Alcohol and drug programs (free)

15 nursing homes (1150-bed capacity, representing all levels of care)

EDUCATIONAL FACILITIES

20 day-care centers (50% free or sliding fee)

| Number | Enrollment | |

|---|---|---|

| Public schools | ||

| Elementary | 32 | 10,007 |

| Middle | 1 | 982 |

| Junior high school | 2 | 1,852 |

| Academic high school | 1 | 1,948 |

| Girls’ vocational high school | 1 | 214 |

| Total | 37 | 15,003 |

| Catholic parochial schools | ||

| Elementary | 15 | 3,379 |

| High schools | 2 | 992 |

| Other | ||

| Regional/technical high school | ||

| County agricultural high school | ||

| Colleges | ||

| Community college: offers wide range of courses, many in health disciplines | ||

| Southeastern University: 4-year programs in most areas | ||

It is important to first look into the socioeconomic structure of the community and determine the type of employment that exists. Tide Water has a large industrial garment area. This leads to the following questions: Is there a high percentage of industrial workers? If so, are they union employees? If this is the case, are they provided with a comprehensive health benefits package, including the provision of dental care? This information is important because it tells whether this population might be able to afford dental care through their jobs.

The population breakdown shows a large percentage of Portuguese living within the community. This indicates that possible cultural and language issues should be considered. In addition, the age distribution indicates that the highest proportion of people is between 20 and 60 years of age, or in the age bracket for the adult working population. There is a large population of school-age children between ages 5 and 19 years living in the community. The age distribution of a community is important to consider because it tells where the target groups are and thus sets up certain priorities for planning. For example, if the majority of the population were of middle to older age, it would not be effective to design a program that would affect only a young population, such as a schoolwide fluoride rinse program.

The educational status of a community provides two perspectives for planning. First, it tells the educational level (years of schooling) obtained by the majority of community members. Second, it may indicate what the community’s values are toward obtaining an education. Planning a health awareness program centered on an educational institution would be successful only if people are attending schools and value the information they receive there.

Knowing the median income of a community is important to a health planner because it indicates the population’s ability to purchase health services. If a segment of the population’s income falls below the poverty level, those individuals would be eligible for federal and state medical assistance programs (provided the individual state participates in such a program), thus making health services financially accessible to these individuals.

Health care must be both geographically and financially accessible if people are going to use it. A look into the community’s public transportation system provides the planner with information regarding a population’s ability to get to health care services. This is especially true for rural communities where roads are unpaved and public transportation is scarce.

Looking at the health care facilities in the community tells the planner what type of services are being provided, the amount of services, and the cost of receiving those services.

The labor data give information about the number of dentists providing care. (The federal government has developed certain labor-to-population ratios that indicate whether a population is considered to be residing in a medically underserved area.) However, just looking at the number of dentists in the community will not give the planner a true picture of whether the number of dentists within the community is sufficient to provide services to the population residing there.

Although the number of dentists in the community may be adequate, the planner must question whether the dentists are available to provide the care. How long does it take to get appointments? What are the dentists’ hours (e.g., do they work after 5 pm or on the weekends)? In addition to knowing the number of dentists, it is necessary to consider what types of services are being provided to whom and for what cost.

Another consideration is the type of practice. Do the dentists accept third-party payments or Medicaid payments? Do they provide comprehensive services, including preventive care? Do they provide dental health education to their patients?

Knowing the fluoride status of a community is also essential for dental planning. In the case study community profile of Tide Water, it is stated that water has been fluoridated since 1995. This indicates that those children born in 1995 and after that year will receive maximum benefits from the fluoridated water. However, it is safe to say that those children born before 1995 may need additional attention with other fluoride measures.

In most cases the politics of the community will determine the direction the program takes. A conservative government attempting to cut costs may be opposed to programs that provide prosthetic services to the medically indigent or elderly. Each local government’s policies may vary in its methods of instituting new programs, allocating funds, hiring personnel, or setting priorities. In addition, the politics of the state government will also shape the overall direction taken by the communities within the state.

By looking at the educational system of a community, the planner can determine the number of schools, the enrollment for each, and the distribution of children among the schools within the community. This information can assist the planner who is developing a school-based program for the community. The public and parochial schools are the ideal settings for dental programs. Moreover, as in countries such as New Zealand, schools also serve as excellent vehicles for providing routine dental care.

The educational facilities should be designed appropriately to accommodate such programs. Teachers, parents, and school administrators should be in support of the programs, and, most important, the need must exist among the school-age population to warrant such programs. In this particular community, with its high percentage of Portuguese-American children, the schools can be a good meeting place in which to open communication channels with the families and to offer support services when needed.

If the planner is designing a dental treatment program for a specific population that is not receiving any care, methods developed by the Indian Health Service (IHS) can convert the survey data into specific resource requirements for treating the population. The IHS is a federal agency within the Public Health Service. It has been involved with extensive surveys on the oral health status of Native Americans. One method it has developed with the use of specific oral health surveys assesses the dental disease prevalence among the population and translates the data into time and cost estimates to treat the population. These surveys for disease prevalence include the decayed, missing, and filled teeth index; the periodontal index; and the simplified oral hygiene index. In addition to determining the dental need, IHS assesses treatment needs, which include prosthetic status, periodontal status, orthodontic status, oral pathology status, and restorative status.

With the use of a mathematic model, dental resource requirements can be computed and projected over a period of time. The data are then translated into time, labor, and facility requirements.

The basic measurement is time. Clinical dental services requirements and labor capability both can be expressed in time units. The IHS, to determine the amount of chair time that is necessary to complete a clinical service, has done various time requirement studies. This unit of time is called a service minute. For example:

| Clinical Service | Time Required (Service Minutes) |

|---|---|

| Complete oral examination | 10 |

| Prophylaxis | 17 |

| Single-surface amalgam | 10 |

LABOR AND FACILITY REQUIREMENTS

The number of dentists and dental auxiliaries, as well as the number of facilities and operators necessary to treat the population, is determined by obtaining the total number of service minutes required for a given population. For example, a random sample of a population was examined, and calculations showed that 70,000 service minutes per year would be required to treat approximately 60% of that population. Based on this figure, the amount of staff required to provide approximately 70,000 service minutes would be one dentist and two dental assistants.9 The number of operators needed to accommodate this dental staff for maximum efficiency would be three.9 The ratios (one dentist to two dental assistants to three operators) have been derived from IHS efficiency studies.

This evaluation is highly statistical. Statistics can set parameters to the problem, but the values and attitudes of persons are equally important. The planner must take into consideration the sociocultural interests or the psychologic readiness of a people to want or use health services. If the community does not agree on which of the array of statistics represents the community’s priorities, little will be done to translate the need identified in the data into effective programs.

DETERMINING PRIORITIES

“Priority determination is a method of imposing people’s values and judgments of what is important onto the raw data.”7 The method can be used for different purposes, such as for setting priorities among problems elicited through a needs assessment. It also can be used for ranking the solutions to the problem.

Given the community profile and analysis of dental survey data, how are priorities established? At this point the community should be involved to assist in the establishment of these priorities. A health advisory committee or task force representing consumers, community leaders, and providers should be established to assist in the development of policies and priorities. Planning with community representation will aid in the program’s implementation and acceptance.

Few dental public health programs meet all the dental needs of the population. With limited resources, it becomes necessary to establish priorities to allow the most efficient allocation of resources. If priorities are not determined, the program may not serve those individuals or groups who need the care most.

Certain factors should be considered in determining priorities. For example, a problem that affects a large number of people generally takes priority over a problem that affects a small number of people. However, if the problem is common colds (affecting a large number of people) competing with Lyme disease (affecting few people), the more serious problem should take priority.

If the health problem is dental disease, generally more than one population group is affected. The following are groups commonly associated with high-risk dental needs:

If the community decides to address the problem of dental caries first, specific groups are more susceptible to dental caries, such as preschool and school-age children and low-income minority groups. The planner then begins to develop plans geared to an identifiable population group.

Once the target group has been identified (based on the dental problem), the type of program should be established. To do this, the planner begins to set program goals and objectives.

DEVELOPMENT OF PROGRAM GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

Program goals are broad statements on the overall purpose of a program to meet a defined problem. An example of a program goal for a community that has an identifiable problem of dental caries among school-age children would be “to improve the oral health of the school-aged children in community X.”

Program objectives are more specific and describe in a measurable way the desired end result of program activities. The objectives should specify the following:

An objective might state, “By 2012, more than 90% of the population ages 6 to 17 years in community X will not have lost any teeth as a result of caries, and at least 40% will be caries free.” This is known as an outcome objective and provides a means of measuring quantitatively the outcome of the specific objective. This approach helps the evaluator and the community know both where the program is and where it hopes to be with respect to a given health problem. It also aids in establishing a realistic timetable for reducing or preventing principal health problems.

Second, objectives are the specific avenues by which goals are met. Process objectives state a specific process by which a public health problem can be reduced and prevented. For example, by 2005 community X will have a public fluoride program to guarantee access to fluoride exposure via the following:

Once the problem has been identified and program goals and objectives have been established describing a solution to or a reduction of the problem, the next step is to state how to bring about the desired results. This area of program planning is referred to as program activities, and it describes how the objectives will be accomplished.

Activities include three components: (1) what is going to be done, (2) who will be doing it, and (3) when it will be done. Activity I. Beginning January 1, 2005, two dental hygienists will be hired to administer a self-applied fluoride rinse program within the public school systems. Activity 2. On March 1, 8, 15, 22, and 30, 2005, a series of 2-day training workshops for parent volunteers will be conducted by the two hygienists at selected public schools in community X. In planning these program activities, it is important to carefully consider the type of resources available, as well as the program constraints.

Resource Identification

Selection of resources for an activity, such as personnel, equipment and supplies, facilities, and financial resources, must be determined by consideration of what would be most effective, adequate, efficient, and appropriate for the tasks to be accomplished. Some criteria that are commonly used to determine what resources should be used follow:

As discussed previously, obtaining the community profile provides the planner with valuable information on available resources. The type of resources needed to develop a dental program and the sources from which they can be obtained are listed in Table 12-1.

Table 12-1 Resource Identification Worksheet

| Resource | Source |

|---|---|

| Personnel | |

| Sponsors or supporters | Public health organizations, professional dental organizations, dental and dental hygiene schools, industry, health consumer groups, government, labor, media, business, foundations, public schools |

| Clinical providers | Dentists, dental hygienists, dental assistants, dental technicians, social workers, health aides, public health nurses, physician’s assistants, nutritionists |

| Nonclinical providers | |

| Planning | Health planning agencies |

| Clerical | Volunteers, students, parents, retirees |

| Educational | Professional organizations, universities, students |

| Analytical | Universities, consulting firms |

| Equipment | |

| Dental units and instruments | Dental supply companies, dental and dental hygiene schools, renovated public health clinics, hospitals, federal government depositories |

| Computers, calculators, filing cabinets | Business, industry, civic groups, hospitals |

| Supplies | |

| Office supplies | Consumer groups, industry, business, and government |

| Dental supplies | Dental supply companies, dental product companies |

| Dental Health Education | |

| Materials | American Dental Association, other professional organizations, public health agencies, dairy councils; local, state, or federal agencies (e.g., National Institute for Dental Research, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) |

| Facilities | Hospitals, health centers, nursing homes, public schools, dental schools, public health clinics, industry, health maintenance organizations |

Identifying Constraints

When planning any program, there are usually as many reasons not to do something as there are reasons to do it. The former are usually considered to be roadblocks or obstacles to achieving a certain goal or objective.

What should be determined at this point are the most obvious constraints that are associated with meeting program objectives. By identifying these constraints early in the planning stages, one can modify the design of the program and thereby create a more practical and realistic plan.

Constraints may result from organizational policies, resource limitations, or characteristics of the community. For example, constraints that commonly occur in community dental programs include limitations of the state’s dental practice act, attitudes of professional organizations, lack of funding, restrictive governmental policies, inadequate transportation systems, labor shortages, lack of or inadequate facilities, negative community attitudes toward dentistry, and the population’s socioeconomic, cultural, and educational characteristics. The community’s source of water (type and location), the lack of fluoride in the water, and the community’s dental health status are also viewed as constraints to program planning. In addition, the amount of time available to complete a project is considered a constraint if that time is too limited to attain the program goals.

One of the best ways to identify constraints is to bring together a group of concerned citizens who might be involved in or affected by the project. As a group that is familiar with the local politics and community structures, these individuals not only can identify the constraints but also can offer alternative solutions to and strategies for meeting the goals.

Alternative Strategies

Being aware of the existing constraints and given the available resources, the planner should then consider alternative courses of action that might be effective in attaining the objectives. It is important to generate a sufficient number of alternatives so that out of that number at least one may be considered acceptable.

The planner must be aware of those alternatives that sound good on the surface but may have certain limitations when closely examined. With limited resources, the planner needs to consider the anticipated costs and the effectiveness of each alternative. A classic example is the use of preventive measures in a community setting. If, for example, the community refused to fluoridate the central water supply, or if a community received its water from individual wells, the planner would look at the alternative preventive measures available in relation to dental caries and the cost savings in terms of needed treatment.

If the preventive measure were considered to be cost-effective, as well as practical to implement, the planner would then choose that measure as the best of the alternatives.

IMPLEMENTATION, SUPERVISION, EVALUATION, AND REVISION

This chapter has concentrated on the planning process: identifying the problem, determining priorities, defining the goals and objectives, identifying the resources and constraints, and considering the alternatives for implementation. The process of putting the plan into operation is referred to as the implementation phase. This phase is ongoing in situations where close supervision and evaluation of the program will ensure effective operations.

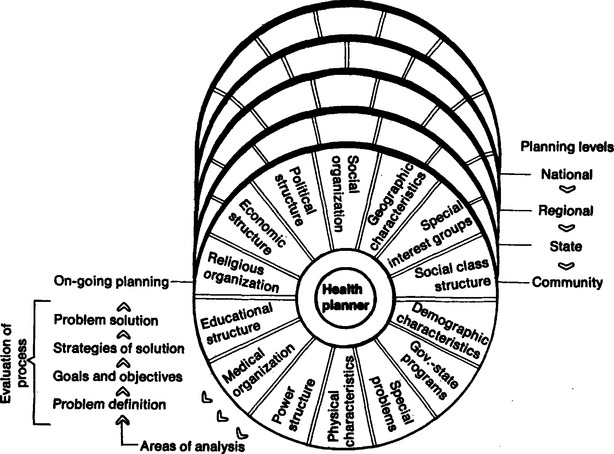

The implementation process, like the planning process, involves individuals, organizations, and the community. Integrating all the external variables to achieve comprehensive planning and implementation requires what Bruhn11 terms an “ecologic” approach (Fig. 12-2). Only through teamwork between the individual and the environment can the implementation be successful.

Fig. 12-2 An ecologic approach to comprehensive health planning.

(From Bruhn JG: Planning for social change: dilemmas for health planning, Am J Public Health 63:604, 1973. © APHA)

Developing an Implementation Strategy

An implementation strategy for each activity is complete when the following questions have been answered:

To develop an implementation strategy, planners must know what specific activity they want to do. The most effective method is to work backward to identify the events that must occur before initiating the activity. For example, in August 2000 Scottish Executive Publications released the text of An Action Plan for Dental Services in Scotland. The plan recognizes the “vital” contribution that dentistry makes to the overall health of the population and the role that dentistry plays as a component of the wider National Health Service system. The plan consists of many parts, but essentially the plan is organized around goals, objectives, and an identification of events that must take place to achieve the goals and objectives. One of the objectives under the heading of Preventing Disease acknowledges the effectiveness of fissure sealants and proposes “targeted prevention for 6- to 16-year-olds,” acknowledging that although “some fissure sealant work is already undertaken in Scotland, it is not sufficiently targeted at those with the greatest need.”12

The activities proposed include the following: (1) the early year’s registration scheme will be reviewed to ensure that it continues to meet its objectives; (2) an enhanced registration payment scheme will be introduced for 6- to 8-year-olds in deprivation categories that will include the requirement for fissure sealing the first molars of these children; (3) consideration will be given to extending this scheme to second molars; and (4) proposals will be developed for oral cancer surveillance and for improved preventive services.

Once stated, the planner may specify what activities must be undertaken to implement the activity. Box 12-2 lists rules for implementation.

BOX 12-2 Rules for Implementation

From National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute: Handbook for improving high blood pressure control in the community, Washington, DC, 1977, US Government Printing Office.

US Government Printing Office

Monitoring, Evaluating, and Revising the Program

Once it has been implemented, the program requires continuous surveillance of all activities. The program’s success is determined by monitoring how well the program is meeting its stated objectives, how well individuals are doing their jobs, how well equipment functions, and how appropriate and adequate facilities are. Before problems arise in any of these areas, adjustments must be made to fine-tune the program.

Evaluation, both informal and formal, is a necessary and important aspect of the program. Evaluation allows us to (1) measure the progress of each activity, (2) measure the effectiveness of each activity, (3) identify problems in carrying out the activities, (4) plan revision and modification, and (5) justify the dollar costs of administering the program and, if necessary, justify seeking additional funds. Each objective should be examined periodically to determine how well it is meeting the program goals. The objective should be stated in measurable terms so that a comparison can be made of what the objective intended to accomplish and what it actually accomplished. Evaluation should address the quality of what is being done. For example, if one of the activities was placing pit and fissure sealants on specific teeth of school-age children, an evaluator would want to assess how well that sealant was placed, the appropriateness of the tooth chosen, and the time involved in placing the sealant on the tooth.

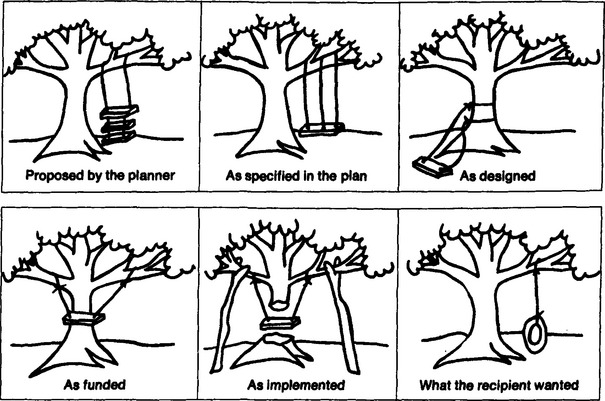

The attitudes of the recipients of the program should be examined to determine whether the program was acceptable to them. Many programs are considered successful by those who run the program; however, the people who have been the recipients of the service may have wanted something very different. Figure 12-3 illustrates this point and gives us a perspective on planning by showing the concept of the planner, the actual plan, the design, the constraints involved, the alternative strategy, and, finally, what the recipient wanted in the first place.

SUMMARY

The twenty-first century requires that the dental health professional, in addition to the delivery of clinical services, must demonstrate awareness of community health issues and provide leadership in the development of programs that address community needs and stress the importance of prevention. Planning is, of course, one of the activities that precedes the implementation of change. The role of the health professional is succinctly expressed in the statement of competencies by the profession of dental hygiene as approved by the house of delegates in 1999: “Dental hygienists must appreciate their role as health professionals at the local, state, and national levels. This role requires the graduate dental hygienist to assess, plan, and implement programs and activities to benefit the general population.”13

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1 Dubos R. So human an animal. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968.

2 Striffier D: Surveying a community and developing a working policy: the administration of local dental programs, University of Michigan, School of Public Health, Proceedings from Fifth Workshop on Dental Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI, 1963.

3 Schulbert H, et al, editors. Program evaluation in the health fields. New York: Human Sciences, 1969.

4 Blum HL. Note on comprehensive planning for health. Berkeley, CA: Comprehensive Health Planning Unit, School of Public Health, University of California, 1968.

5 Provision of dental care in the community, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, 1973, Proceedings from the Third Annual Course in Dental Public Health, Waldenwoods Conference Center, Hartland, MI, May 22-26, 1966.

6 Banfield EC, et al, editors. Politics, planning, and the public interest: the case of public housing in Chicago. The Free Press, 1995.

7 Spiegel A, et al, editors. Basic health planning methods. Germantown, MD: Aspen Systems, 1978.

8 Reece SM. Community analysis for health planning: strategies for primary care practitioners. Nurse Pract. Oct 1998;23(10):53-54.

9 Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Public Health Service. Dental program efficiency criteria and standards for the Indian Health Service. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1974.

10 Model standards for community preventive health services. A report to the U.S. Congress for the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, Aug 1979.

11 Bruhn J. Planning for social change. Am J Public Health. 1972;63:7.

12 Guidance Note Issued by the Queen’s Printer for Scotland. An Action Plan for Dental Services in Scotland. Aug 10, 2001;2:1-5.

13 American Dental Hygienists Association Profile of ADHA. Available at www.adha.org/aboutadha/profile.htm.