Image production

Objectives

• Describe the process of radiographic image formation.

• Explain the process of beam attenuation.

• Identify the factors that affect beam attenuation.

• Describe the x-ray interactions termed photoelectric effect and Compton effect.

• State the composition of exit radiation.

• State the effect of scatter radiation on the radiographic image.

• Explain the process of creating the various shades of gray in the image.

• Differentiate among digital and film-screen imaging.

• Define fluoroscopy and describe the process of image intensification.

Key terms

absorption

attenuation

brightness gain

coherent scattering

Compton effect

Compton electron

conversion factor

differential absorption

electrostatic focusing lenses

exit radiation

fluoroscopy

flux gain

fog

image intensification

image receptor

input phosphor

ionization

latent image

manifest image

minification gain

output phosphor

photocathode

photoelectric effect

photoelectron

remnant radiation

scattering

secondary electron

tissue density

transmission

Introduction

To produce a radiographic image, x-ray photons must pass through tissue and interact with an image receptor (a device that receives the radiation leaving the patient) such as a digital imaging system. Both the quantity and quality of the primary x-ray beam affect its interaction within the various tissues that make up the anatomic part. In addition, the composition of the anatomic tissues affects the x-ray beam interaction. The absorption characteristics of the anatomic part are determined by its composition, such as thickness, atomic number, and tissue density (compactness of the cellular structures). Finally, the radiation that exits the patient is composed of varying energies and interacts with the image receptor to form the latent or invisible image.

Differential absorption

The process of image formation is a result of differential absorption of the x-ray beam as it interacts with the anatomic tissue.

MAKE THE PHYSICS CONNECTION

Differential absorption is the difference between the x-ray photons that are absorbed photoelectrically and those that penetrate the body.

The term differential is used because varying anatomic parts do not absorb the primary beam to the same degree. Anatomic parts composed of bone absorb more x-ray photons than parts filled with air. Differential absorption of the primary x-ray beam creates an image that structurally represents the anatomic area of interest (Figure 8-1).

CRITICAL CONCEPT

Differential Absorption and Image Formation

A radiographic image is created by passing an x-ray beam through the patient and interacting with an image receptor, such as a digital imaging system. The variations in absorption and transmission of the exiting x-ray beam structurally represent the anatomic area of interest.

Beam attenuation

As the primary x-ray beam passes through anatomic tissue, it loses some of its energy. Fewer x-ray photons remain in the beam after it interacts with anatomic tissue. This reduction in the energy or number of photons in the primary x-ray beam is known as attenuation. Beam attenuation occurs as a result of the photon interactions with the atomic structures that compose the tissues. Two distinct processes occur during beam attenuation in the diagnostic range: absorption and scattering.

Absorption

As the energy of the primary x-ray beam is deposited within the atoms composing the tissue, some x-ray photons are completely absorbed. Complete absorption of the incoming x-ray photon occurs when it has enough energy to remove (eject) an inner-shell electron. The ejected electron, called a photoelectron, quickly loses energy by interacting with nearby tissues.

The ability to remove (eject) electrons, known as ionization, is one of the characteristics of x-rays. In the diagnostic range, this x-ray interaction with matter is known as the photoelectric effect.

MAKE THE PHYSICS CONNECTION

Photoelectric interactions occur throughout the diagnostic range (i.e., 20 kVp to 120 kVp) and involve inner-shell orbital electrons of tissue atoms. For photoelectric events to occur, the incident x-ray photon energy must be equal to or greater than the orbital shell binding energy. In these events the incident x-ray photon interacts with the inner-shell electron of a tissue atom and removes it from orbit. In the process the incident x-ray photon expends all of its energy and is totally absorbed.

With the photoelectric effect, the ionized atom has a vacancy, or electron hole, in its inner shell. An electron from an outer-shell drops down to fill the vacancy. Because of the difference in binding energies between the two electron shells, a secondary x-ray photon is emitted (Figure 8-2). This secondary x-ray photon typically has very low energy and is therefore unlikely to exit the patient.

CRITICAL CONCEPT

X-ray Photon Absorption

During attenuation of the x-ray beam, the photoelectric effect is responsible for total absorption of the incoming x-ray photon.

The probability of total photon absorption during the photoelectric effect depends on the energy of the incoming x-ray photon and the atomic number of the anatomic tissue. The energy of the incoming x-ray photon must be at least equal to the binding energy of the inner-shell electron. After absorption of some of the x-ray photons, the overall energy or quantity of the primary beam decreases as it passes through the anatomic part.

Scattering

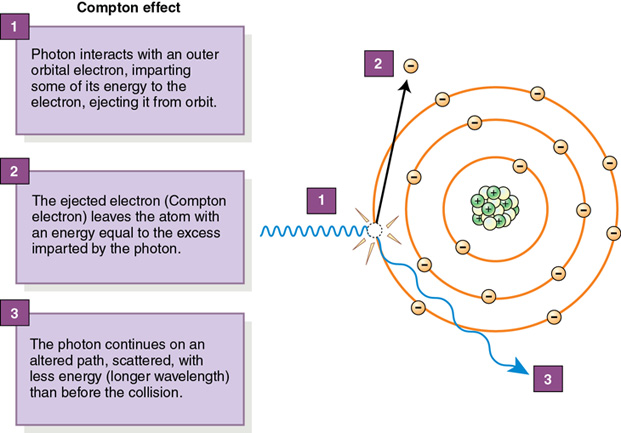

Some incoming photons are not absorbed but instead lose energy during interactions with the atoms composing the tissue. This process is called scattering. It results from the diagnostic x-ray interaction with matter known as the Compton effect. The loss of some energy of the incoming photon occurs when it ejects an outer-shell electron from a tissue atom. The ejected electron is called a Compton electron or secondary electron. The remaining lower-energy x-ray photon changes direction and may leave the anatomic part to interact with the image receptor (Figure 8-3).

CRITICAL CONCEPT

X-ray Beam Scattering

During attenuation of the x-ray beam, the incoming x-ray photon may lose energy and change direction as a result of the Compton effect.

Compton interactions can occur within all diagnostic x-ray energies and are, therefore, an important interaction in radiography. The probability of a Compton interaction occurring depends on the energy of the incoming photon. It does not depend on the atomic number of the anatomic tissue. For example, a Compton interaction is just as likely to occur in soft tissue as in tissue composed of bone. However, if the tissue has more complex atoms, there are more opportunities for interaction. With higher atomic number particles, such as bone, if the energy of the incoming photon is appropriate (high enough), more scatter will occur; otherwise, more absorption will take place. For Compton interactions to occur, the energy of the photon is more important, whereas the atomic number of the tissue is just the opportunity for x-ray interactions.

At higher kilovoltages within the diagnostic range, the percentage of photoelectric interactions generally decreases while the percentage of Compton interactions is likely to increase. Box 8-1 compares photoelectric and Compton interactions. Scattered and secondary radiations provide no useful information and must be controlled during radiographic imaging.

MAKE THE PHYSICS CONNECTION

The problem with Compton scatter interacting with the image receptor is that it is not following its original path through the body and strikes the image receptor in the wrong area. In so doing, it contributes no useful information to the image and results only in image fog. Because most scattered photons are still directed toward the image receptor and result in image fog, it is desirable to minimize Compton scattering as much as possible.

Coherent scattering is an interaction that occurs with low-energy x-rays, typically below the diagnostic range. The incoming photon interacts with the atom, causing it to become excited. The x-ray does not lose energy but changes direction. Coherent scattering could occur within the diagnostic range of x-rays and may interact with the image receptor, but it is not considered an important interaction in radiography.

If a scattered photon strikes the image receptor, it does not contribute any useful information about the anatomic area of interest. If scattered photons are absorbed within the anatomic tissue, they contribute to the radiation exposure to the patient. In addition, if the scattered photon leaves the patient and does not strike the image receptor, it could contribute to the radiation exposure of anyone near the patient.

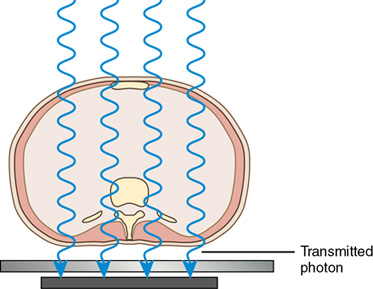

Transmission

If the incoming x-ray photon passes through the anatomic part without any interaction with the atomic structures, it is called transmission (Figure 8-4). The combination of absorption and transmission of the x-ray beam provides an image that structurally represents the anatomic part. Because scatter radiation is also a process that occurs during interaction of the x-ray beam and anatomic part, the quality of the image created is compromised if the scattered photon strikes the image receptor.

The preceding discussion focused on photon interactions that occur in radiography when using x-ray energies within the moderate or diagnostic range. Higher-energy x-rays, beyond the diagnostic range, result in other interactions, pair production and photodisintegration. X-ray interactions beyond the diagnostic range are important in radiation therapy.

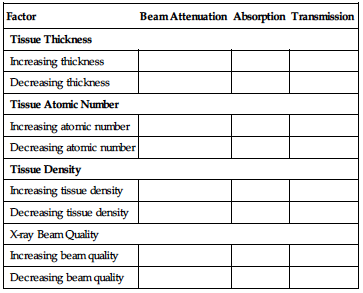

Factors affecting beam attenuation

The amount of x-ray beam attenuation is affected by the thickness of the anatomic part, its tissue atomic number and tissue density, and the energy of the x-ray beam.

Tissue thickness.

For a given anatomic tissue, increasing its thickness increases beam attenuation by either absorption (see Figure 8-5, A, B) or scattering. X-rays are attenuated exponentially and generally reduced by approximately 50% for each 4 to 5 cm of tissue thickness (Figure 8-6). The thicker the anatomic part, the more x-rays are needed to produce a radiographic image. The thinner the anatomic part, the fewer x-rays are needed to produce a radiographic image.

Type of tissue.

Tissue composed of a higher atomic number such as bone attenuates the x-ray beam more than tissue composed of a lower atomic number such as fat. The higher atomic number indicates there are more atomic particles for interaction with the x-ray photons. X-ray absorption is more likely to occur in tissues composed of a higher atomic number when compared with tissues composed of a lower atomic number (Figure 8-7). Tissues that absorb more x-rays demonstrate increased brightness in a digital image. Tissues that transmit more x-rays (absorb fewer x-rays) demonstrate decreased brightness in the digital image.

Tissue density.

Matter per unit volume—or the compactness of the atomic particles composing the anatomic part—also affects the amount of beam attenuation. For example, muscle and fat tissue are similar in composition; however, their atomic particles differ in compactness and therefore tissue density varies. Muscle tissue has atomic particles that are more dense or compact and therefore attenuate the x-ray beam more than fat cells. Bone is composed of tissue with a higher atomic number, and the atomic particles are more compacted or dense. Anatomic tissues are typically ranked based on their attenuation properties. Four substances account for most of the beam attenuation in the human body: bone, muscle, fat, and air. Bone attenuates the x-ray beam more than muscle, muscle attenuates the x-ray beam more than fat, and fat attenuates the x-ray beam more than the air. The atomic number of the anatomic part and its tissue density affect x-ray beam attenuation.

X-ray beam quality.

The quality of the x-ray beam or its penetrating ability affects its interaction with anatomic tissue. Higher-penetrating x-rays (shorter wavelength with higher frequency) are more likely to be transmitted through anatomic tissue without interacting with the tissues’ atomic structures. Lower-penetrating x-rays (longer wavelength with lower frequency) are more likely to interact with the atomic structures and be absorbed. The kilovoltage selected during x-ray production determines the energy or penetrability of the x-ray photon and this affects its attenuation in anatomic tissue (Figure 8-8). Beam attenuation is decreased with a higher-energy x-ray beam and increased with a lower-energy x-ray beam (Table 8-1).

TABLE 8-1

| Factor | Beam Attenuation | Absorption | Transmission |

| Tissue Thickness | |||

| Increasing thickness | |||

| Decreasing thickness | |||

| Tissue Atomic Number | |||

| Increasing atomic number | |||

| Decreasing atomic number | |||

| Tissue Density | |||

| Increasing tissue density | |||

| Decreasing tissue density | |||

| X-ray Beam Quality | |||

| Increasing beam quality | |||

| Decreasing beam quality | |||

CRITICAL CONCEPT

Factors Affecting Beam Attenuation

Increasing tissue thickness, atomic number, and tissue density increases x-ray beam attenuation because more x-rays are absorbed by the tissue. Increasing the quality of the x-ray beam decreases beam attenuation because the higher-energy x-rays penetrate the tissue.

Imaging effect.

When the attenuated x-ray beam leaves the patient, the remaining x-ray beam, referred to as exit radiation or remnant radiation, is composed of both transmitted and scattered radiation (Figure 8-9). The varying amounts of transmitted and absorbed radiation (differential absorption) create an image that structurally represents the anatomic area of interest. Scatter exit radiation (Compton interactions) that reaches the image receptor does not provide any diagnostic information about the anatomic area. Scatter radiation creates unwanted exposure on the image called fog. Methods used to decrease the amount of scatter radiation reaching the image receptor are discussed in later chapters.

The areas within the anatomic tissue that absorb incoming x-ray photons (photoelectric effect) create the white or clear areas (increased brightness) on the displayed image. The incoming x-ray photons that are transmitted create the black areas (decreased brightness) on the displayed image. Anatomic tissues that vary in absorption and transmission create a range of dark and light areas (shades of gray) (Figure 8-10). The various shades of gray or brightness recorded in the radiographic image make anatomic tissue visible. Skeletal bones are differentiated from the air-filled lungs because of their differences in absorption and transmission.

CRITICAL CONCEPT

Image Brightness

The range of brightness levels visible after image processing is a result of the variation in x-ray absorption and transmission as the x-ray beam passes through anatomic tissues. In addition, the radiographer can manipulate the quality of the primary x-ray beam to affect its attenuation and modify the visibility of anatomic structures.

Image characteristics and exposure techniques are discussed in more detail in later chapters.

Image receptors

Less than 5% of the primary x-ray beam interacting with the anatomic part actually reaches the image receptor, and an even lower percentage is used to create the radiographic image. The exit or remnant radiation leaving the patient interacts with an image receptor to create the latent (invisible) image. This latent image is not visible until processed to produce the manifest (visible) image.

Two types of image receptors are used in radiography: digital and film-screen. A more detailed discussion of each type of image receptor can be found in Chapter 12.

Digital image receptors

Digital imaging can be accomplished by using a specialized image receptor that acquires the latent image, from which the computer processes the visible image for display on a monitor. There are several types of digital image receptors used in diagnostic imaging. Unlike film-screen imaging in which the film is the medium to acquire, process, and display the image, digital imaging includes three separate stages. The digital image receptor acquires the latent image, the computer processes the image, and the monitor displays the visible image. Regardless of the type of digital-imaging receptor, the radiographic image is composed of digital data and can then be altered in a variety of ways.

Film-screen image receptors

Although film-screen imaging is nearly obsolete, familiarity with film-screen imaging is still necessary. Film-screen imaging uses a cassette, or light-tight container, for the radiographic film, which is placed between two intensifying screens within the cassette. The exit radiation interacts with the intensifying screens and is converted to visible light. The intensifying screens serve to intensify the action of the x-rays, thereby reducing radiation exposure to the patient. Because x-rays have more energy than visible light, fewer x-rays can be used to image the area of interest when using intensifying screens. The visible light energies emitted from the intensifying screens are proportional in quantity or intensity to the radiation exiting the patient. The film records the latent image based on the pattern of remnant x-rays and the light produced by the intensifying screens. The absorption of visible light by the film’s emulsion initiates a conversion process that is continued by chemical processing to create a permanent visible image. The composition and type of film and intensifying screens, in addition to the quality of film processing, have an important role in radiographic imaging.

CRITICAL CONCEPT

Differential Absorption and Image Receptor

The process of differential absorption for image formation remains the same regardless of the type of image receptor. The varying x-ray intensities exit the anatomic area of interest to form the latent image.

Both digital and film-screen radiography create a static image of the anatomic area of interest. Dynamic imaging, or fluoroscopy, provides imaging of the movement of internal structures.

Dynamic imaging: Fluoroscopy

Fluoroscopy (Figure 8-11) differs from static imaging by its use of a continuous beam of x-rays to create images of moving internal structures that can be viewed on a display monitor. Internal structures, such as the vascular or gastrointestinal systems, can be visualized in their normal state of motion with the aid of special liquid or gas substances (contrast media) that are either injected or instilled. Although there are newer digital technologies available for fluoroscopy, the basics of image-intensified fluoroscopy are still important and need to be understood. During image-intensified fluoroscopy, the internal structures can best be visualized when the images are brighter. Creating a brighter image is accomplished with image intensification.

Image intensification.

Image intensification (Figure 8-12) is the process in which the exit radiation from the anatomic area of interest interacts with a light-emitting material (input phosphor) for conversion to visible light. The light intensities (energies) are equal to the intensities of the exit radiation and are converted to electrons by a photocathode (photoemission). The electrons are focused by electrostatic focusing lenses and accelerated toward an anode to strike the output phosphor and create a brighter image.

CRITICAL CONCEPT

Fluoroscopy

Dynamic imaging of internal anatomic structures can be visualized with the use of an image intensifier. The exit radiation is absorbed by the input phosphor, converted to electrons, sent to the output phosphor, released as visible light, and then converted to an electronic video signal for transmission to the display monitor.

Brightness gain.

A brighter image is a result of the high-energy electrons striking a small output phosphor. Accelerating the electrons increases the light intensities at the output phosphor (flux gain). The reduction in size of the output phosphor image as compared with the input phosphor image also increases the light intensities (minification gain). Brightness gain is the product of both flux gain and minification gain and results in a brighter image on the output phosphor. Although the term brightness gain continues to be used, it is now common practice to express this increase in brightness with the term conversion factor. Conversion factor is an expression of the luminance at the output phosphor divided by the input exposure rate.

CRITICAL CONCEPT

Brightness Gain

A brighter image is created on the output phosphor when the accelerated electrons strike a smaller output phosphor.

The image light intensities from the output phosphor are converted to an electronic video signal and sent to a display monitor for viewing. Additional filming devices such as spot film or cine (movie film) can be attached to the fluoroscopic system to create permanent radiographic images of specific areas of interest. Additionally, the electronic video signal created from the output phosphor light intensities during image-intensified fluoroscopy can be converted to digital data and displayed on a high-resolution display monitor. Once the fluoroscopic image is digitized, a computer can manipulate the image in a variety of ways. Fluoroscopy will be discussed in detail in Chapter 14. Whether the radiographic image is displayed on a computer monitor or on film, the process of differential absorption for image formation remains the same. The varying x-ray intensities exiting the anatomic area of interest form the image.

Several important steps in creating a radiographic image have been discussed in this and the previous chapters. Further discussion of radiographic image characteristics, exposure technique selection, image receptors, control of scatter radiation, and problem solving are included in subsequent chapters.

CRITICAL CONCEPT

Image Formation

The process of differential absorption for image formation remains the same regardless of the type of imaging system. The varying x-ray intensities exiting the anatomic area of interest form the radiographic image. The radiographic image can be viewed on a computer display monitor or film.

Summary

• A radiographic image is a result of the differential absorption of the primary x-rays that interact with the varying tissue composition of the anatomic area of interest.

• Beam attenuation occurs when the primary x-ray beam loses energy as it interacts with anatomic tissues.

• Beam attenuation is affected by tissue thickness, atomic number, tissue density, and x-ray beam quality.

• X-rays have the ability to eject electrons (ionization) from atoms within anatomic tissue.

• Three primary processes occur during x-ray interaction with anatomic tissues: absorption, transmission, and scattering.

• Total absorption of the incoming x-ray photon is a result of the photoelectric effect.

• Scattering of the incoming x-ray photon is a result of the Compton effect.

• Scatter radiation reaching the image receptor provides no useful information and creates unwanted exposure or fog on the radiograph.

• A radiographic image is composed of varying brightness levels that structurally represent the anatomic area of interest.

• Digital and film-screen image receptors receive the exit radiation from the area of interest to record the latent image.

• Digital imaging includes three separate stages to acquire, process, and display the image, whereas film is the medium for all three stages. Fluoroscopy allows imaging of the movement of internal structures for viewing on a display monitor.

• Image intensification creates a brighter image for viewing by the combination of flux gain and minification gain.

• The process of differential absorption remains the same for image formation regardless of the type of image receptor: digital, film-screen, or fluoroscopy.

Critical thinking questions

1. During beam attenuation, what occurs at the molecular level of anatomic tissues to affect the radiation exiting the patient?

2. Why is scatter radiation detrimental to the radiographic image, patient, and personnel in the vicinity?

3. How does the response of film-screen, digital, and fluoroscopic image receptors differ with respect to radiation intensity exiting the patient?

Review questions

1. Which of the following describes the process of radiographic image formation?

2. X-rays have the ability to eject electrons from atoms. This is known as:

3. The x-ray interaction with anatomic tissue that is responsible for scattering is:

4. Which of the following will increase beam attenuation?

5. Factors that decrease x-ray absorption include:

6. What type of imaging system uses an emulsion to absorb the radiant energy?

7. Which component of the image intensifier converts the light intensities into electrons?

8. The purpose of image intensification during fluoroscopy is to:

a. decrease motion during dynamic imaging.

b. increase the brightness of the fluoroscopic image.

9. Which component of an image intensifier converts the electrons to light intensities?

10. The process of differential absorption to form a radiographic image is the same for digital and film-screen image receptors.