The place of clinical supervision in modern healthcare

INTRODUCTION

This chapter examines the progression of clinical supervision from being a luxury in healthcare practice, to becoming a central activity in a qualified health professional’s continuing professional development legitimized by sweeping modernization reforms, particularly in UK healthcare.

Since the concept of clinical supervision was first introduced into nursing and health visiting over a decade ago, health professionals, other than, but allied to, nursing are now developing workable clinical supervision schemes. It therefore seems an opportune time to collaboratively reflect on what is meant by clinical supervision and some of the lessons being learned through its development.

A distinct advantage of nursing and health visiting having prepared some ground in clinical supervision in terms of organizational infrastructuring through the development of strategies, policies and training is the very real potential for corporate collaboration and sharing of experiences and professional perspectives on clinical supervision.

While for many, clinical supervision in practice is needed, it has also to be valued. An ongoing challenge for the development of formal and planned clinical supervision time for qualified health professionals is not just simply finding the time but convincing them and their managers that engaging in regular clinical supervision can offer significant benefits and is worth supporting in practice.

Not unlike the nursing professions, allied health professions are taking responsibility for the development of clinical supervision and facing the challenges of patient care (rather than staff care) being the priority for practice, whilst wrestling to clarify what is actually meant by clinical supervision, and often with limited resources. Despite these challenges, there undoubtedly is more general awareness of the importance of clinical supervision in healthcare and the development of many different approaches and practices.

In a previous edition, Driscoll (2000:79) outlined a resulting doomsday scenario if nurses and health visitors were not committed to developing workable clinical supervision structures or engaging in the process. Organizations without committed staff were left with three choices. Some of those original organizational choices would now seem more relevant than ever as allied health professionals begin to implement clinical supervision.

Persevere with the slow uptake of clinical supervision in practice through increased training and continue to ‘wait and see’.

Persevere with the slow uptake of clinical supervision in practice through increased training and continue to ‘wait and see’.

Become disillusioned with the slow uptake and begin to dismantle the clinical supervisory infrastructures that have been put in place.

Become disillusioned with the slow uptake and begin to dismantle the clinical supervisory infrastructures that have been put in place.

Insist that clinical supervision is such a good idea that it is made mandatory for all healthcare practitioners.

Insist that clinical supervision is such a good idea that it is made mandatory for all healthcare practitioners.

While the first option might be the option of choice, it is becoming clear that clinical supervision represents one of many possibilities in satisfying continuing professional development and regulatory needs. It is interesting to note how clinical supervision is increasingly becoming ‘less optional’ in some organizations as healthcare demands robust auditable structures for staff support and professional development. This is perhaps not surprising with health provision reforming dramatically between inpatient and community provision (Department of Health 2000a, 2004a, 2006) and health professionals’ roles expanding rapidly (Department of Health 2006b, Department of Health 2000b, 2003a, Department of Health & Royal College of Nursing 2003) to meet the increase in service-led delivery systems and expectations. In some respects whilst the gradual roll-out of clinical supervision continues and embeds itself into the culture of healthcare organizations, the rapid demands being placed on staff today are even greater and if ever there was a clear mandate for clinical supervision it is now.

One wonders what might be the case if clinical supervision continued to be valued as an auditable mechanism for professional support and development in organizations but remained dormant in health professionals’ practice? Might the doomsday scenario (mandatory supervision) then be applied and what might clinical supervision look like then?

As authors, we both remain optimistic that the continued corporate developments in clinical supervision and the good work that has, and continues to be, achieved is now being bolstered by support from the allied health professions. This being the case, we see it as essential that those new to the concept of clinical supervision at least have a working understanding of the concept that will enable them to make some informed choices. In this respect, our intention is that this chapter will demystify clinical supervision and stimulate reflection on what is wanted from clinical supervision and how this can be achieved in practice.

SUPERVISORY STRUCTURES IN HEALTHCARE PRACTICE

Perhaps it is useful to remind oneself that supervision in healthcare is not a new thing although there may well be differences in the emphases or functions of supervision. Therefore, the relationships that occur across the whole spectrum of supervisory activities in the healthcare professions will differ depending on the intentions of those engaging in those processes. For instance, while preceptorship is not an unfamiliar term in nursing and radiography as being a formalized source of support for new professional registrants, in other professions the term mentorship is used. While there are obvious professional nuances, it might be preferable to consider skills and attributes already being used that count as supervisory practice — whether from the perspective of ‘supervisor’ or ‘being supervised’.

Dimensions of supervision

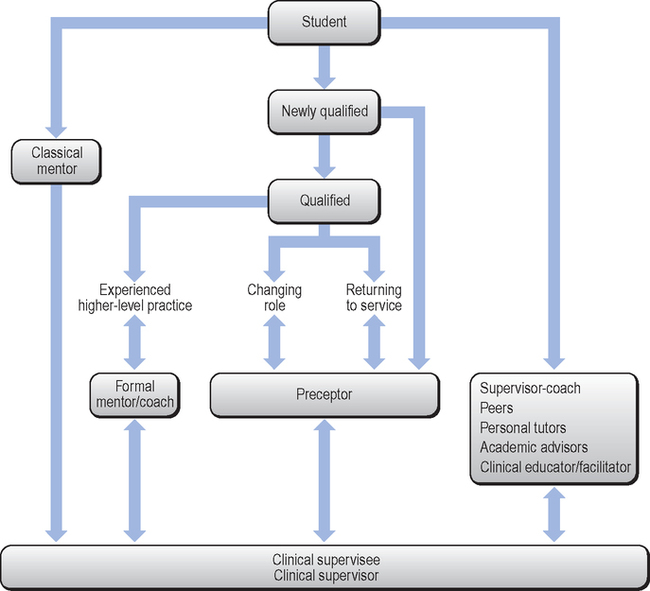

Supervision can be seen as happening in two dimensions (Figure 1.1) and this is a useful way of considering the different types of supervision that are already happening in practice before going on to consider the notion of clinical supervision itself.

Just thinking about the enormous range of supervisory activities gives an indication of the variable nature of the roles of supervisor and supervisee in healthcare and what might be able to be built upon, in terms of the potential development of clinical supervisor and supervisee roles.

Supervisory activities can be said to be two-dimensional, in that they are likely to be ‘formal’ and ‘planned’ on the one hand and ‘informal’ and ‘ad-hoc’ on the other. The four quadrants in Figure 1.1 relate to the ‘where’ and ‘when’ of supervision (and there are likely to be additions from your own experience of supervision). The top right quadrant is particularly useful to consider in adapting supervision activities because it takes into account unexpected happenings in healthcare practice that emerge outside planned supervision times and that may, in themselves, present as more regular supervisory opportunities.

You might be surprised at the amount of supervisory opportunities in clinical practice and perhaps this supports the often stated notion that ‘clinical supervision is happening anyway’.

We wonder how many readers would think of the development of clinical supervision as being a ‘formal and planned’ activity instead of it being a quickfix solution to an immediate problem in practice. We suggest it might initially be appropriate to make clinical supervision a prominent fixture in practice. Making time for clinical supervision on a par with formal mentoring sessions or monthly team meetings will probably make it more difficult to just ‘quietly forget about’ it, as these supervisory activities will then be built into the infrastructure of healthcare practice in much the same way as is a medical ward round or case conference.

While clinical supervision may be a new concept to many practitioners, the three main components of supervision in healthcare practice can be summarized as:

Supervised practice and learning

We suspect that most readers will have either been through or are going through some form of supervised practice and learning as part of being a health professional. Both parties in this form of supervision–supervisee relationship operate in well-defined roles. The basic parameters include fulfilling institutional, professional and individual learning outcomes as part of a course of pre-qualifying or post-qualifying study. (Confusingly, terms such as clinical education and clinical supervision have often been used interchangeably in this context.) Supervised practice often involves directly instructing or offering advice to the learner as well as having an assessing and supporting function. Mentoring may be considered an example of supervised practice (Higgins & McCarthy 2005) although mentoring functions and roles differ across healthcare disciplines and cultures (Gibson & Heartfield 2005, Morton-Cooper & Palmer 2000:35). Aside from scholarly activities mentoring is also associated with career progression and personal development (Andrews & Wallis 1999, Mills et al 2005) and again cited as clinical supervision (Chow & Suen 2001).

The formal introduction of preceptorship in UK nursing as another form of supervised practice and support was introduced in the 1990s in response to evidence suggesting, rightly, that learning about the newly qualified staff nurse role only really began after rather than before qualification (Maben & Macleod-Clark 1996). It has since transformed from being an informal buddying system with a more experienced clinical colleague focusing on skills and role transition in the work setting, to becoming a way of accessing formal support and in-service education for newly qualified staff in practice (CSP 2005a, O’Malley et al 2000).

Supervised practice and learning focuses on the skills and attributes required by an individual to become a newly qualified and accountable health professional but, once that individual becomes qualified, organizational supervision is largely concerned with the maintenance of a professional level of performance. Professional values and organizational expectations of behaviour are defined through the production of formal processes and procedures (such as policies, standards, job descriptors and the joint setting of performance objectives as in appraisal and professional development planning).

The focus of organizational or managerial forms of supervision is on the performance of the individual or group of individuals in the wider organization.

You will not be surprised to discover that this type of supervision is traditionally thought of as a form of employer surveillance. While that statement might be a generalization, there is undoubtedly a tendency in this form of supervision towards managing risk and setting goals and objectives based on corporate strategies. The notion of surveillance is only confirmed when these strategies cover areas of disciplinary procedure. However, this type of supervision is not unusual; some junior health professionals in, for example, physiotherapy and occupational therapy are rotated through departments in which supervision by a more senior member of staff is expected. Therefore, perhaps, it is not difficult to see how suspicion can be aroused when the term supervision is used in practice.

Supportive supervision

Perhaps as a consequence of heavy-handed supervision experiences, and in order to survive the rigours of clinical practice, health professionals have always created individualized support systems at work. (You may wish to compare again the different types of support in Figure 1.1 with your own practice.) Some emerge almost intuitively, from working with and knowing that you can trust particular people who are prepared to listen to your concerns. Butterworth (1998:8) describes, as an example of informal peer support, the ‘tea break / tear break’ used by nurses as a way of letting colleagues share in the stressful clinical experiences which had affected their working day. Such ad-hoc and informal encounters play a vital part in coping with everyday clinical practice. While not exactly clinical supervision, such support networks can be considered the cement that holds the building up, without which it might implode!

We wonder, for health professionals who do not have a booked diary of patients, if reinstating formalized dinner breaks, based away from clinical areas, might offer opportunities for supportive supervision and reduce professional isolation (as opposed to grabbing a sandwich and sitting alone in the busy work environment). This is not to say that every lunch break should constitute clinical supervision, but by meeting regularly to discuss work, away from the workplace, opportunities could be created for the provision of any support that might be needed.

The changing face of healthcare practice so vividly described by Ferguson (2005:293) clearly endorses the need for formal as well as informal supportive supervision mechanisms in practice:

… Health services have been integrated into the community, and the professionals that remain in ‘traditional’ institutions experience a much changed landscape. Staff numbers have reduced, middle management has been downsized and, information technology and flexible work practices bring an unfamiliar isolation for the health worker. The needs of the individual health professional now, more than ever before need urgent attention …

Morton-Cooper and Palmer (2000:209) provide a much needed graphic representation that we have adapted to help summarize the range of supervision schemes, outlined previously, that would likely be encountered in becoming and being a healthcare professional (Figure 1.2).

In times of change and challenge in healthcare practice it is normal for practitioners to feel uncertain and confused. It is also normal, in our view, to expect organizations to provide and actively develop the shaping of workable and supportive supervision schemes that are, in turn, actively utilized by practitioners. So, as there is already a range of supervisory structures in healthcare practice, why the emergence of another supervisory structure called clinical supervision?

THE EMERGENCE OF CLINICAL SUPERVISION IN HEALTHCARE SETTINGS

Not unlike other supervisory processes, clinical supervision is a particular kind of professional conversation that happens in the workplace. But, unlike some of those other supervisory processes, clinical supervision sets out not to be the kind of conversation that involves giving people advice, assessing them or solving their problems for them, but one in which you provide space, time and professional support for colleagues to reflect on their encounters with patients or fellow workers (Burton & Launer 2003a).

As a means of professional learning and support, clinical supervision is not a new idea within certain health and social care professions, for example:

social work (Browne & Bourne 1996, Kadushin & Harkness 2002, Morrison 2003),

social work (Browne & Bourne 1996, Kadushin & Harkness 2002, Morrison 2003),

counselling and psychotherapy (Hawkins & Shohet 2000, Haynes et al 2003, Hughes & Pengelly 1997, Page & Wosket 2002, Tudor & Worrall 2004),

counselling and psychotherapy (Hawkins & Shohet 2000, Haynes et al 2003, Hughes & Pengelly 1997, Page & Wosket 2002, Tudor & Worrall 2004),

midwifery (Kirkham 1996, Nursing & Midwifery Council 2005a, Skoberne 2003, Thomas 2005),

midwifery (Kirkham 1996, Nursing & Midwifery Council 2005a, Skoberne 2003, Thomas 2005),

mental health professionals (Ask & Roche 2005, NMAG 2004, Scaife 2002),

mental health professionals (Ask & Roche 2005, NMAG 2004, Scaife 2002),

occupational therapy (COT 1997, Hall 1998, Sweeney et al 2001),

occupational therapy (COT 1997, Hall 1998, Sweeney et al 2001),

speech and language therapy (RCSLT 1996), and

speech and language therapy (RCSLT 1996), and

some nursing specialities (Butterworth et al 1998, Cutcliffe et al 2001).

some nursing specialities (Butterworth et al 1998, Cutcliffe et al 2001).

Not surprisingly much of the current literature on the development of clinical supervision for nurses and allied health professionals, particularly in the UK, has emerged from these professional disciplines where supervision has already become an integral part of clinical practice and often a mandatory accreditation requirement.

For other health-related disciplines, clinical supervision is just beginning to emerge in practice, for example:

dietetics (Burton 2000, Kirk et al 2000),

dietetics (Burton 2000, Kirk et al 2000),

the medical profession (Burton & Launer 2003b:3, Grant et al 2003, McDonald 2002),

the medical profession (Burton & Launer 2003b:3, Grant et al 2003, McDonald 2002),

occupational health (Billington et al 2005),

occupational health (Billington et al 2005),

physiotherapy (CSP 2005b, Clouder & Sellars 2004, Sellars 2000),

physiotherapy (CSP 2005b, Clouder & Sellars 2004, Sellars 2000),

podiatry (Weaver 2001),

podiatry (Weaver 2001),

radiography (Hussain 2004, Sood & Driscoll 2004),

radiography (Hussain 2004, Sood & Driscoll 2004),

learning disabilities nursing (Malin 2000),

learning disabilities nursing (Malin 2000),

practice nursing (Cheater & Hale 2001, Cutcliffe & McFeely, 2001, Debreczeny 2003, Greaves 2004),

practice nursing (Cheater & Hale 2001, Cutcliffe & McFeely, 2001, Debreczeny 2003, Greaves 2004),

complementary therapies (Ryan 2004, Tate et al 2003, Wood 2003), and

complementary therapies (Ryan 2004, Tate et al 2003, Wood 2003), and

prison nursing (Freshwater et al 2001, 2002).

prison nursing (Freshwater et al 2001, 2002).

More detailed reviews about the emergence of clinical supervision can be found in:

Grover (2002), Grauel (2002), Hunter and Blair (1999), McMahon and Patton (2002), Rose and Best (2005) and Sellars (2004) for allied health professionals,

Grover (2002), Grauel (2002), Hunter and Blair (1999), McMahon and Patton (2002), Rose and Best (2005) and Sellars (2004) for allied health professionals,

Kilminster and Jolly (2000) for medical staff, and

Kilminster and Jolly (2000) for medical staff, and

Bond and Holland (1998), Cutcliffe and Lowe (2005), Fowler (1996), Gilmore (2001), Hyrkas et al (1999), Stevenson (2005), Winstanley and White (2003) and Yegdich (2002) for nursing.

Bond and Holland (1998), Cutcliffe and Lowe (2005), Fowler (1996), Gilmore (2001), Hyrkas et al (1999), Stevenson (2005), Winstanley and White (2003) and Yegdich (2002) for nursing.

From our experience in facilitating workshops, the term ‘supervision’ when applied to healthcare practice, whether for senior qualified practitioners or student learners, still manages to conjure up images of being ‘watched’ or ‘controlled’ in some way by those responsible for the overall management of the service delivery. This is despite the efforts made to dissociate the continuing professional development and more supportive mechanism of clinical supervision for qualified clinical staff from more organizationally led models of supervision such as appraisal, individual performance reviews and caseload management. Yegdich and Cushing (1998) go further and suggest that in nursing a name change is needed because while the need for clinical supervision is largely unquestioned, and it is viewed as a ‘good thing’, its implementation, particularly in nursing, has been slow and tortuous and met with scepticism, ridicule and resistance and this remains a cause for concern (Cottrell 2002, Yegdich 2002:251).

Since clinical supervision, as a term, has such a poor reputation why not simply change its name, as Yegdich and Cushing (1998) suggest, and thus change its standing in the healthcare community? Unfortunately, clinical supervision has already many names, being described interchangeably as:

a form of critical companionship, being a metaphor for a person-centred helping relationship for facilitating emancipatory learning experiences in practice (Manley et al 2005, Titchen 2003),

a form of critical companionship, being a metaphor for a person-centred helping relationship for facilitating emancipatory learning experiences in practice (Manley et al 2005, Titchen 2003),

clinical facilitation (Lambert & Glacken 2005),

clinical facilitation (Lambert & Glacken 2005),

clinical education (Sellars 2004),

clinical education (Sellars 2004),

development coaching (Driscoll & Cooper 2005),

development coaching (Driscoll & Cooper 2005),

guided reflection (Johns 2000, Todd & Freshwater 1999), or simply

guided reflection (Johns 2000, Todd & Freshwater 1999), or simply

professional supervision (Ferguson 2005), among others.

professional supervision (Ferguson 2005), among others.

However, this proliferation of terms indicates that professionals in healthcare see that struggling with the concept of clinical supervision is worthwhile. For example, at an Egalitarian Consultation Meeting (ECM) considering multiprofessional clinical supervision in mental health, participants were given the task of constructing their own particular version of clinical supervision (as an alternative to the received wisdom that there is only one right way); time and space were deliberately set aside during the meeting for the accomplishment of the task (Stevenson 2005, Stevenson & Jackson 2000).

Clearly there is a need for a diversity of clinical supervision approaches as the original idea of a ‘one fit all’ approach has become outdated. Our own appreciation and experiences of clinical supervision suggest that there is a need to continue to promote a clinical ‘soup’ ervision and experiment with eclectic blends to validate whether or not they are useful processes for practitioners engaging in clinical supervision. However, as Power (1999:11) warns:

… the real problem is that the more words we use to avoid the ones that we have — and should be using (clinical supervision) — the more we dig a bigger hole for ourselves …

It is perhaps reassuring to note that confusion often experienced by introducing the term ‘clinical supervision’ to practitioners in UK healthcare would seem to be not only a national but also an international issue. For instance, clinical supervision relates to the supervised practice of nursing students on clinical placements in Canada and New Zealand (Mills et al 2005, Rose & Best 2005), and is a term that has been used interchangeably with managerial supervision and supervised practice in nursing in Australia (Winstanley & White 2003, Yegdich & Cushing 1998) until quite recently.

Cutcliffe and Lowe (2005) also cite significant differences in the perception of the purpose of clinical supervision when comparing North American and European conceptualizations.

In North America, clinical supervisors are seen as being clinical experts in a given speciality and often have a managerial role.

In North America, clinical supervisors are seen as being clinical experts in a given speciality and often have a managerial role.

In Europe, rather than being thought of as clinical experts, clinical supervisors might be peers and be expected to be supportive at facilitating reflective practice and helping the supervisee solve practice difficulties.

In Europe, rather than being thought of as clinical experts, clinical supervisors might be peers and be expected to be supportive at facilitating reflective practice and helping the supervisee solve practice difficulties.

The latter approach has also been significant in the development of clinical supervision in Scandinavia (Hyrkas 2005, Hyrkas et al 1999, Palsson & Norberg 1995, Paunonen & Hyrkas 2001, Severinsson & Hallberg 1996).

The latter approach has also been significant in the development of clinical supervision in Scandinavia (Hyrkas 2005, Hyrkas et al 1999, Palsson & Norberg 1995, Paunonen & Hyrkas 2001, Severinsson & Hallberg 1996).

Whatever the international differences, the profile of clinical supervision in UK healthcare is undoubtedly being shaped both by governmental policy and professional ideas about its development. These two influences create a dynamic tension affecting its implementation because of the differences in managerial and professional agendas; the former being concerned with developing a safe and accountable health professional, the latter more concerned with continued personal learning and support. Although Malin (2000) questions whose interests are best being served, both agendas appear to have a place in describing the overall functions of clinical supervision and are discussed in more detail in the next section.

Clinical governance, a central plank in governmental healthcare reforms, is a statutory quality framework through which all NHS organizations are accountable for continually improving the quality of their services (Department of Health 1999, 1998a, 1998b, NHSCGST 2005, McSherry & Pearce 2002, Scally & Donaldson 1998). It has dramatically raised the profile of continuing professional development (CPD) and work-based learning initiatives because its statutory professional regulations must be met (Butterworth & Woods 1999, CSP 2005b, Gustafsson & Fagerberg 2004, NMC 2005b).

Thus the demand for accountability has highlighted the role of clinical supervision in the process of expanding professional roles and change and reform in healthcare (Department of Health 2006b, Department of Health 2000b, 2000c, 2000d, 2003a, Department of Health & Royal College of Nursing 2003, Sellars 2004). More recently, healthcare organizations have had to demonstrate that they have staff support structures in place, such as clinical supervision, as they have become auditable mechanisms within the NHS (CHAI 2004) and have spawned a number of multiprofessional organizational policies on clinical supervision (Clough et al 2005, Harder et al 2005).

Although clinical supervision is not mandatory for most UK health professionals, it is viewed as best practice; to the point that it is fast becoming a ‘must do’ in healthcare organizations as a method of ongoing staff development. Also, with the revised pay and conditions now including supervision in job descriptions and supervision generally becoming a core dimension of the Knowledge and Skills Framework for continued career progression (Department of Health 2003b, 2004b, Royal College of Nursing 2005), its importance is acknowledged.

A recent lengthy consultation of allied health professions endorsed clinical supervision as a legitimate form of continuing professional development (HPC 2004, 2005) and a number of professional bodies have developed specific clinical supervision frameworks (BDA 2000, COT 1997, CSP 2005b, SCoR 2003a, 2003b, RCSLT 1996).

While clinical supervision has become a more visible concept, one wonders who will be responsible for the policing and development of ‘less optional’, if not quite mandatory, clinical supervision schemes in practice. It could be argued that the development of clinical supervision schemes might be easier to implement in organizations that view them as not ‘optional’ but necessary and who set about formalizing frameworks and policies. However, Edwards et al (2005) remain sceptical and posit that, despite these measures, the actual finding of the time and resources to implement such schemes will remain an ongoing issue. In addition, what of those health professionals who simply choose not to engage in clinical supervision where it is not a definite professional requirement but rather seen as just ‘best practice’?

Despite some very real challenges associated with the concept of clinical supervision, there seems to be some consensus of opinion about the ingredients of the clinical supervision encounter:

The current debate is around the proportions of each of these elements that one must include to distinguish supervision from managerial interventions, from learning and from therapy per se, or more specifically to fully understand the purpose and functions of clinical supervision in practice.

THE PURPOSE AND FUNCTIONS OF CLINICAL SUPERVISION

The importance of taking regular time out to talk about practice is a key consideration in clinical supervision and a consistent feature of working definitions of clinical supervision from the literature, for instance:

… a structured, formal process that enables dieticians to discuss their work with an experienced practitioner, trained to facilitate clinical supervision. This discussion should be a guided reflection on current practice and should be used to learn from experience …

Talking about clinical practice in clinical supervision also provides a learning opportunity and a way of influencing change in future practice(s):

… an opportunity for a professional to change a story about a working encounter by holding a conversation with another professional.

While regularly talking about practice is a key consideration in clinical supervision, unless it is properly formalized and legitimized as a practice-based activity (as important as working with clients and patients), it will continue to be difficult to implement. This aspect is discussed further in Chapter 9. Actively finding the time, in among all of the pressures that exist at work, demonstrates not only a commitment to the process of clinical supervision, whether as a supervisor or supervisee, but also values the importance of taking time for yourself while you continue to care for others.

The plethora of definitions of clinical supervision in the literature raises, perhaps unrealistic, expectations about the effectiveness of the process for both practitioners and their practice. For instance, along with definitions previously cited in this chapter, they include the following premises (or are they promises?):

a process for maintaining and safeguarding standards of care in practice;

a process for maintaining and safeguarding standards of care in practice;

being evidence of lifelong learning in practice;

being evidence of lifelong learning in practice;

a recognition of individual practitioner responsibilities and accountabilities under clinical governance;

a recognition of individual practitioner responsibilities and accountabilities under clinical governance;

contributing to significant improvement in healthcare delivery through regular reflection on practice with others;

contributing to significant improvement in healthcare delivery through regular reflection on practice with others;

a process for the development of practitioner knowledge and subsequent increased professional skills and competence;

a process for the development of practitioner knowledge and subsequent increased professional skills and competence;

a method of practice-based learning contributing to the continuing professional development of the practitioner;

a method of practice-based learning contributing to the continuing professional development of the practitioner;

a formal method of support to influence personal change in order to improve future practice.

a formal method of support to influence personal change in order to improve future practice.

You may be able to think of other reasons why effective clinical supervision raises the expectations for practice. But, none the less, these expectations could be utilized by clinical supervisors to encourage the development of competence in practitioners as well as themselves.

It is important to begin to think of clinical supervision not only in terms of individual outcomes for healthcare professionals, but also as a way of improving the quality of healthcare delivery. A popular and well thought out UK nursing definition proposed by Bond and Holland (1998:12) continues to offer not just the ‘what’ but ‘why’ of clinical supervision and would seem to encompass many of the principles enshrined in definitions of clinical supervision:

Clinical supervision is regular protected time for facilitated, in-depth reflection on clinical practice. It aims to enable the supervisee to achieve, sustain and creatively develop a high quality of practice through the means of focused support and development. The supervisee reflects on the part she plays as an individual in the complexities of the events and the quality of her practice. This reflection is facilitated by one or more experienced colleagues who have expertise in facilitation and the frequent on-going sessions are led by the supervisee’s agenda. The process of clinical supervision should continue throughout the person’s career, whether they remain in clinical practice or move into management, research or education.

While definitions can offer substance to a rather nebulous concept like clinical supervision it is unlikely that one definition will be able to capture all the complexities of healthcare practice. However, having in the back of your mind the ‘what’ and ‘why’ of clinical supervision can be helpful when trying to explain to colleagues what it is and what it sets out to do. (This is particularly relevant when those colleagues are covering for you in your practice.)

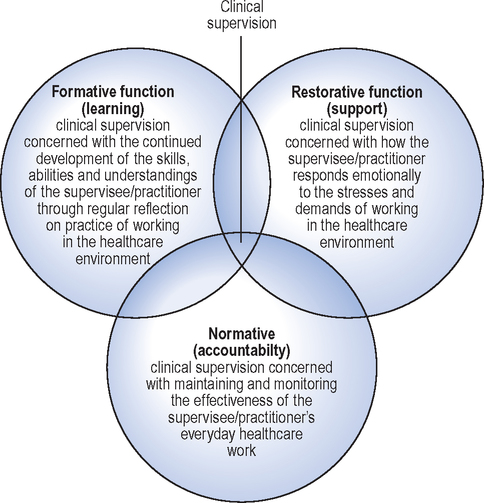

While self-reported practitioner outcomes may not be that difficult to evaluate, improvements in patient/client outcomes remain the ‘holy grail’ for clinical supervision and will continue to be a major challenge because of the multitude of other variables that prevail or have an effect on multiprofessional healthcare delivery. However, organizational data exist that might be correlated with the onset of clinical supervision. For instance, Brigid Proctor’s (1986) Interactive Framework of Clinical Supervision is currently one of the most widely used clinical supervision frameworks, particularly in nursing practice (Sloan & Watson 2002, Winstanley & White 2003). The framework, based on an original framework by Kadushin (1992), has since formed the basis for a number of evaluations in practice (Butterworth et al 1997, Bowles & Young 1999) and a national audit tool for measuring the effectiveness of clinical supervision in organizations, the Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale (Winstanley 2000), and has been influential in the development of standards in clinical supervision across Wales (Rafferty et al 2003), which is outlined in more detail in Chapter 10.

The three interactive functions of clinical supervision (Figure 1.3) present a practical framework that we have used in training clinical supervisors. It offers at least three different perspectives or foci and can be used as an aide when the supervisee is preparing for a clinical supervision discussion.

Referring back to Bond and Holland’s (1998) definition, it is also possible to see how Proctor’s functions of clinical supervision might relate to each other in practice. It is interesting to speculate that clinical supervisors may have preferred functions or styles that they use in clinical supervision. For example:

for practitioners who have an unavoidable dual function, being both a clinical supervisor and manager of a supervisee, the normative element may be a more natural function to use during a supervisory discussion;

for practitioners who have an unavoidable dual function, being both a clinical supervisor and manager of a supervisee, the normative element may be a more natural function to use during a supervisory discussion;

someone working in a mental health setting might adopt more of a supportive function; or

someone working in a mental health setting might adopt more of a supportive function; or

a clinical education facilitator acting as a clinical supervisor might adopt more of a learning function.

a clinical education facilitator acting as a clinical supervisor might adopt more of a learning function.

The three elements or functions of clinical supervision were always intended to be applied equally, but in reality they tend to overlap or compete because supervisees often present with a complexity of issues. A clinical supervision model cannot be applied too rigidly; it has to be a flexible tool that can initiate or guide clinical supervision.

Although Proctor’s framework is a useful tool for conceptualizing supervision by breaking it into component parts, like most models, it is an artificial construct that is unlikely to totally reflect reality. It might therefore be considered a useful but limited guide that cannot be expected to cover every eventuality.

It is our contention that Proctor’s framework is a useful beginner’s guide to clinical supervision and that practitioners may then wish to progress or experiment with other supervision frameworks as the supervisor and supervisee become more confident in the supervisory relationship and more open to exploring other perspectives. For example, in Proctor’s framework there is not a function specifically examining the relationship of the supervisee to a patient/client, whereas in some psychological-based frameworks this perspective is prominent. (This is dealt with in more detail in Chapter 5.)

An example from Sood and Driscoll (2004) of the discussions in clinical supervision using Proctor’s framework is summarized in Box 1.1.

WHAT ARE YOUR EXPECTATIONS FOR ENGAGING IN CLINICAL SUPERVISION?

To make more informed decisions on how the process of clinical supervision can be incorporated into everyday healthcare practice, we think it is important to have explored the background to its emergence and the different agendas and expectations that come with such an initiative. Looking back over what has been discussed in this chapter, you might feel that the emphasis has largely been on identifying what clinical supervision may or may not be, according to other people’s ideas — people who think they know about you and your practice (perhaps including us!).

You may wish to compare your thoughts with some of ours contained in Box 1.2 (not in any order of priority). These ideas will be further expanded in Chapters 3 and 4.

As you will have already noted, the push towards the implementation of clinical supervision is being driven by:

structural changes in that provision,

structural changes in that provision,

public concerns about education and clinical practice, and

public concerns about education and clinical practice, and

an overdue recognition of the need for active support in practice.

an overdue recognition of the need for active support in practice.

Again, you may feel that clinical supervision is being developed, or simply wished for, by those who are at arm’s length from the reality of everyday practice.

While facilitating clinical supervision workshops, we have been interested to note how different clinical supervision appears to be when looked at from different points of view. For example:

a newly qualified occupational therapist who is wanting information on what is expected of them as a supervisee,

a newly qualified occupational therapist who is wanting information on what is expected of them as a supervisee,

a superintendent physiotherapist in a primary care trust who will be managing the initiative in clinical practice, or

a superintendent physiotherapist in a primary care trust who will be managing the initiative in clinical practice, or

an executive director seeking ways of maximizing the resources being set aside for its development in line with clinical governance.

an executive director seeking ways of maximizing the resources being set aside for its development in line with clinical governance.

Whatever the perspective, for clinical supervision to continue to be sustained in everyday healthcare practice it must have some demonstrable outcomes, not just for the practitioner (perhaps as professional development), but, more importantly, for practice (by the way that care is delivered through development and improvement).

To improve your clinical supervisory techniques, you have to engage regularly in actual clinical supervision activities. Thus, by regular participation, you develop, through your own supervisory experience(s), a method and format that works for you. In other words, you are able to apply a way of engaging in clinical supervision that makes sense not just to the supervisor, but to the supervisee and, just as importantly, through such commitment and effort, makes an impact on practice.

Perhaps a starting point for your own reflections, or even getting started in clinical supervision, might be to consider how participating in clinical supervision could contribute beneficially to your practice.

Many of the benefits described in the evaluative literature have a tendency to report on outcomes for practitioners themselves rather than for patients/clients.

There still exist unanswered questions about organizations continuing to invest in the development of clinical supervision without also having some form of demonstrable return in relation to users of the health services (Edwards et al 2005). Interestingly this would seem to be a topical issue for a discipline like psychotherapy where regular supervision has already beeen an integral part of practice and training for many years (Bambling 2004).

However, Debreczeny (2003:76) argues that if healthcare professionals are more confident and capable in the work setting then professional practice will be improved and patients/clients will benefit. Ongoing research continues to be concerned with these issues.

Some of the broad benefits cited for engaging in regular clinical supervision in nursing have been (Butterworth et al 1997, Cheater & Hale 2001, Hyrkas 2005, Severinsson & Borgenhammar 1997, Teasdale et al 2001):

increased feelings of support,

increased feelings of support,

reductions in professional isolation,

reductions in professional isolation,

reductions in levels of stress,

reductions in levels of stress,

Current research and evaluations being carried out within the allied health professions in healthcare on the benefits of clinical supervision also highlight a similar range of positive outcomes (Grover 2002, Sellars 2000, 2004, Strong et al 2003, Tate et al 2003, Weaver 2001). Strong et al (2003) classified the following themes as important benefits in the supervisory practice of allied health professionals in a mental health service that also seem to resonate as functions of clinical supervision previously outlined by Proctor (1986):

Professional development and support in practice.

Professional development and support in practice.

A method of quality assurance and competent best practice.

A method of quality assurance and competent best practice.

Support for organizational issues such as recruitment and retention.

Support for organizational issues such as recruitment and retention.

Increased professional discipline growth and identity.

Increased professional discipline growth and identity.

Promotion of work-based learning and the development of new skills.

Promotion of work-based learning and the development of new skills.

Clearly, for clinical supervision to become fully integrated into everyday clinical practice, it first requires health professionals to have a dialogue in order to come to a shared understanding of:

what the key features of it are when compared to other forms of supervision that already exist, and

what the key features of it are when compared to other forms of supervision that already exist, and

how to move from being something ‘extra’ ordinary in practice to something more ordinary.

how to move from being something ‘extra’ ordinary in practice to something more ordinary.

In many cases, in our view, this involves examining the structures that already exist and how they can be adapted for use in clinical supervision practice.

CONCLUSION

It would seem that the debate about the place of clinical supervision for health professions in modern healthcare is clearly well advanced in some disciplines while for others it is just beginning. In the expansion of professional roles in the modernization of services through policy directives, it is possible to see a blurring of professional boundaries in which the development of collaborative supervision schemes (Clough 2005, Harder et al 2005) and training may well become the norm. Although perhaps a challenge at the outset, it does seem not only increasingly likely but also a common-sense (as well as cost-efficient) way forward — as opposed to individual disciplines scrapping for limited resources and developing their own schemes within the same healthcare organizations.

The professional agenda does include a compelling argument for all practitioners to now have access to clinical supervision whether mandatory, non-optional or statutory. The key, as always, is in the detail, in which the weighting for the range of different intentions and purposes surrounding clinical supervision still requires some clarification. One framework will not fit all, but a range of methods and formats should be available and agreed on at the local level.

The time has come to encourage practitioners to develop a form of clinical supervision that will meet their individual needs, by simply starting regular professional conversations in practice. Through these conversations, supervisees will be able to process the personal experiences they are struggling with rather than focus on the policies or procedures that others perceive as important. In other words, practitioners should be actively supported to challenge the received wisdom of those who think they know what ‘should’ happen in clinical supervision.

While this chapter has been an attempt to offer an overview of the development of clinical supervision, it has also tried to demystify and debunk some of the myths that still surround it and impede its continued development. It might be argued that the bar for the organizational development of clinical supervision has been raised so high as to now have become a universal remedy for all the challenges in modernizing professional healthcare rather than a practice improvement potential. Perhaps when all the hype is stripped away from the veneer of clinical supervision we are left with what Darley (2001) refers to as:

… a useful if rather dull process whereby practitioners are listened to by someone who has the ability (organizationally, interpersonally or professionally) to help them … help in this context means to resolve any concerns they may have with their work and to help develop their practice by a process of guided reflection …

A legitimate opportunity remains and it is now up to healthcare professionals to collectively shape what they themselves consider to be clinical supervision before it becomes shaped by others on their behalf.