Supported reflective learning: the essence of clinical supervision?

INTRODUCTION

The previous chapter examined the increased legitimacy of clinical supervision and why its development and implementation is important in modern healthcare. This chapter continues that theme and, as in the previous edition, I persist with the idea that supported reflective learning is, in itself, the very essence of the clinical supervision encounter. However, in the spirit of reflection and acknowledging that the use of questions is central to the process of learning about reflection (Todd & Freshwater 1999), I pose some questions that I hope might be indicative of the sorts of questions you, the reader, might pose about reflection and reflective practice.

Throughout the chapter I use the term reflection as the process of going about reflection and reflective practice as it applies to the work of the health professional. While this is perhaps a simplistic way of looking at what is a complex concept, my purpose is to offer a starting point before addressing the question posed in the title of the chapter (Supported reflective learning: the essence of clinical supervision?). Using this as a platform, I begin to expose some of my own thoughts and understandings which you may, or may not, agree with and pose further questions about the relationship between reflective practice and clinical supervision. However, it is not my intention for this chapter to form a comprehensive literature review of reflective practice, as very readable analyses are available elsewhere (Bulman & Schutz 2004, Ghaye & Ghaye 2004, Johns 2002, Johns & Freshwater 2005, Rolfe et al 2001, Moon 2004, Tate & Sills 2004, Taylor 2005).

Writing the introduction to this chapter reminded me of how I used to initiate students into the subject of reflective practice at the beginning of a training programme by placing what I think is called a figure–ground illusion on the projector. As an example of the vagaries of the process of simple visual perception, it is a useful metaphor for the more complex vagaries of conceptual perception (e.g. ‘seeing’ reflective practice) (Figure 2.1).

There are at least three perceptual, or ‘seeing’, experiences evoked by the examination of Figure 2.1 and these experiences can also be evoked by the examination of the concept of reflective practice:

Some of you might see it straight away.

Some of you might see it straight away.

Some of you might see it if is pointed out to you.

Some of you might see it if is pointed out to you.

Some of you might still not see it despite it being pointed out to you.

Some of you might still not see it despite it being pointed out to you.

(Just in case, I have placed what Figure 2.1 depicts after the On Reflection box at the end of the chapter!)

The point I am trying to make here, as I was with my students, is that some people cannot see the value of reflective practice straight away and sometimes even after they have had a chance to experience it they still fail to appreciate its value. As regards to this chapter the same is likely to apply and I encourage you to come to your own conclusions about whether reflection and reflective practice might be the essence of clinical supervision. In any event, I give you some of my personal signposts to help you make more sense of reflection and reflective practice and decide on whether utilizing clinical supervision in your practice will, or will not, assist you on your lifelong learning journey as a qualified health professional.

WHY THE NEED TO BE REFLECTIVE WHEN I ROUTINELY THINK ABOUT WHAT I DO IN MY CLINICAL PRACTICE?

Reflective practice is often seen as representing a choice for health professionals to be reflective or not to be reflective about their clinical practice, but as Bright (1995) suggests, in reality, such a dichotomy is false as everyone needs to engage in some form of self-reflection about their professional work. Although we will explore this in more detail later in the chapter, I suspect that many of you reading this might agree with the idea that as you think about your clinical practice as a matter of routine anyway there is no need to set aside specific ‘reflective’ time. This attitude presents a real challenge to health professionals as it hampers attempts to legitimize intentional reflection as an everyday activity in clinical practice. I tend to agree with Jarvis (1992), who points out that while no profession can claim to have reflective practice per se, what individuals within that profession have is an ability and a choice to practise reflectively. This does not mean that they will choose to reflect, only that the potential to do so exists within them.

So, although you may think you routinely reflect about your clinical practice, how often do you actually do so? I wonder how many of you when asked this question might sympathize with Smythe (2004), who questions whether there is even time to think, let alone be reflective, in busy work environments in which people are having to rush around from one demand to another in a world that expects an instant everything.

Reflection has a variety of definitions but which one you favour will depend on how relevant it is to your own situation. One of the best descriptions for me is given by Boyd and Fales (1983):

… reflective learning is the process of internally examining and exploring an issue of concern, triggered by an experience, which creates and clarifies meaning in terms of self, and which results in a changed conceptual perspective …

So, according to this definition, reflecting on an experience is an intentional learning activity requiring an ability to analyse the self in relation to what has happened or is happening and make judgements regarding this.

However, what can pass for reflection might not be reflection; thinking about an experience or event is not always purposeful and does not necessarily lead to new ways of thinking or behaving.

Of course reflection is not simply about managing the risk of healthcare; it is also an intentional method of learning which should lead to improvement in oneself and in one’s practice.

In an increasingly patient-led UK health service (Department of Health 2005) health professionals are dealing with people who, because of their individual natures, require staff to be responsive and reflective instead of people who are simply carrying out what may seem like routine and repetitive tasks.

Although reflective practice is an opportunity to capture, examine and challenge some of the set patterns of working, such examination might lead to the realization that there is a need for change. This implies disruption and effort and it is much simpler to continue working in the same set ways — unless something unusual happens that forces some form of reflection. (For example, Jones (2004) cites a paramedic practice where there was a tendency to formally reflect on dramatic events but ignore the routine day-to-day things that they also dealt with — but I suggest that this is a feature of the reflective practice of many other health professionals new to the idea of practising reflection.)

There will be moments, such as in emergency situations, where to physically stop and think in the midst of the action would be inappropriate and even life-threatening. But, in situations like these, formally replaying or having a debriefing session about the events at a respectable distance in time after the incident has occurred would be beneficial. Such reflections not only establish what went wrong but also affirm best practice.

While it is obviously unreasonable and physically impossible to continually reflect on everything that happens in practice, there are gains to be made in regularly stopping to think about everyday practice. Engaging in regular clinical supervision activities offers opportunities not only to have a self-dialogue about selected elements of practice but also to acquire new perspectives and/or mentally reframe familiar ways of working.

It also needs acknowledging at this stage of the chapter that reflective practice is not just confined to clinical supervision; reflective processes are likely to be just as valuable across the whole spectrum of the healthcare organization.

HOW DOES THE PROCESS OF REFLECTION RELATE TO LEARNING IN AND FOR PRACTICE?

For most healthcare professionals their first exposures to reflection and reflective practices are likely to occur in the formal education setting of their initial training, with an expectation that these practices will become features of their continuing professional development (Tate 2004:8). (For me it was while undergoing teacher training as part of the requirement to become a clinical teacher in neurosurgical nursing.)

At a macro level, the process of reflection and reflective practice could be seen to begin with education providers. United Kingdom universities and colleges of higher education are institutionally responsible for ensuring that appropriate standards are being achieved in the education of healthcare professionals. The Quality Assurance Agency (QAA), in partnership with the regulating bodies of healthcare professionals, periodically reviews teaching and learning activities and part of its remit is to ensure that provision is being made for reflection time so that the students will to be able to link theory and practice (Department of Health/National Midwives Council/NHS/Health Professions Council 2004).

Exposure to reflection and reflective practice is critical, not only for supporting the fledgling reflective practitioners during their education and training, but also in helping them view reflective activities as being just as important after their qualification and in their development as continual learners in practice. Beyond registration, reflective practices, including clinical supervision, are periodically audited under clinical governance (described in the previous chapter). Clearly, reflective practice as a strategic learning activity in the development of health professionals is a central plank supporting change and reform in healthcare organizations.

At a micro level, the process of reflection, beginning in an educational setting, is often grounded in experiential learning and learning from experience. Usher and Soloman (1999) make a distinction between the two:

the former is an internal dialogue which constructs experiences in a particular way to give them meaning to the individual; that is, in a cyclical fashion knowledge and learning are derived from experiences and future experiences are given meaning from the gained new knowledge and learning;

the former is an internal dialogue which constructs experiences in a particular way to give them meaning to the individual; that is, in a cyclical fashion knowledge and learning are derived from experiences and future experiences are given meaning from the gained new knowledge and learning;

in the latter learning emerges from direct involvement in an everyday context, e.g. the ‘live’ supervision of a learner by someone more experienced and/or the observation by the learner of the practice of the experienced person (such as a mentor).

in the latter learning emerges from direct involvement in an everyday context, e.g. the ‘live’ supervision of a learner by someone more experienced and/or the observation by the learner of the practice of the experienced person (such as a mentor).

Although there are endless possibilities as a qualified health professional for ‘live’ supervision and learning from a new situation, here we concern ourselves with the stages in the process of reflection that have formed many reflective frameworks and have formed the basis of preparation for and offered structure to clinical supervision.

Moon (2004:115), after examining a number of experiential learning stages proposed by a number of theoretical authors, synthesized eight sequential stages in the process of reflection (Box 2.1) that a learner will necessarily travel through.

It will be noted that the reflective sequence requires learners to have the experience before returning to replay it in a classroom, either to themselves or in a clinical supervision situation.

One is struck by the need to be committed to this type of learning as a reflective practitioner. It incorporates being able to:

The emphasis is towards learning and subsequent forward action, but it is likely that in order to learn, some ‘unlearning’ of favoured ways of working might need to take place.

If one’s first exposures to reflection and reflective practice (in an educational setting) are to be of benefit and to inspire confidence in it as a positive method of learning, then one needs to be not only supported through the exposures but also challenged.

For many students, attempts at reflection are very likely to be assessable (removing the element of choice) and this may induce concern about the process. A key difference between reflecting as part of an assessed training programme and as a qualified health professional in clinical practice, I would suggest, is that in the former the learner has a limited choice as to whether to reflect or not — that potentially might limit learning or reduce it to a superficial exercise, which in turn could have implications for a clinical supervision situation after qualification.

In taking on the responsibilities for the continuance of reflection and reflective practice through clinical supervision as part of a continuing professional development activity, facilitators are preparing not only potential supervisees, but also supervisors.

It is also very likely, in relation to this, that facilitators themselves will be engaged in a peer process of reflection and support in order not only to experience the process first-hand but also to be in a better position to empathize with students, thus making these early exposures the hoped for, positive experiences.

It would seem that for reflective practice to make a difference, not only to individual health professionals but also to their clinical practice, it needs to be more than simply a process; it needs to include a commitment to action-ing that learning (reflexive action). In this respect, I agree with Atkins and Murphy (1993) that this might not necessarily involve acts that can be observed by others. The individual learner makes a commitment of some kind on the basis of what has been learned as action; no one can ‘see’ this decision to commit. Although it is the final stage of the reflective cycle, the commitment potentially begins the cycle again.

Clinical supervision (applied reflective practice) would seem to give qualified health professionals a legitimate opportunity to regularly stop and think in the midst of practice and, if there is a commitment to reflexive action in terms of improving that practice, then whole areas of healthcare could be transformed.

HOW MIGHT ENGAGING IN REFLECTION SPECIFICALLY SUPPORT THE WORK OF THE HEALTH PROFESSIONAL?

The late Donald Schon (1983, 1987) considered two kinds of knowledge that professionals use in practice:

‘Technical rationality’ depends on the possession and utilization of logic and should be used by professionals in their practice. It is based on empirical and scientific knowledge (often developed in university or research environments). Within this technical–rational mode of thinking, it is anticipated that health professionals will apply ‘theoretical’ knowledge to solve their practical problems.

‘Tacit knowledge’, on the other hand, is ‘taken for granted’ knowledge. So, for professionals, technical rationality is perceived as the more appropriate way of thinking. However, while technical rationality is useful to explain practice ‘as it should be’, it often fails to address the complex nature of practice ‘as it really is’.

Schon (1983:42) describes the complex nature of professional practice as the ‘swampy lowland’, where situations can become confusing ‘messes incapable of technical solution’. In other words, while a practitioner from any discipline does require a sound theoretical and scientific basis from which to operate, this, in itself, does not always produce effective practice. It is within this quagmire of uncertainty and personal conflict that the more ‘tacit’ or intuitive knowledge of practice is realized, and this has been popularized as the ‘theory–practice gap’ debate (Ousey 2000, Rolfe 1996).

However, as Griffiths and Tann (1992) suggest, the distinction between theory and practice (or reflection and action) is not a gap or difference in knowledge, but a mismatch between the personally held beliefs of health professionals and publicly held theories; these mismatches are perceived as contradictions. Reflective practice, therefore, has been developed to help health professionals articulate their own beliefs and compare them to publically held theories and, thus, help them to make sense of the ‘swampy lowland’ of complex practice in which there appear to be more questions than straightforward answers.

Chris Johns (2005:2) in his definition of reflection offers hope to health professionals as he invites us to enter and fully embrace the conflict of contradictions contained in Schon’s ‘swampy lowlands of practice’ rather than avoid it or simply use reflection as a bridge to cross the terrain:

Reflection is being mindful of self, either within or after experience, as if a window through which the practitioner can view and focus self within the context of a particular experience, in order to confront, understand and move toward resolving contradiction between one’s vision and actual practice. Through the conflict of contradiction, the commitment to realize one’s vision, and understanding why things are as they are, the practitioner can gain new insights into self and be empowered to respond more congruently in future situations within a reflexive spiral towards developing practical wisdom and realizing one’s vision as a lived reality. The practitioner may require guidance to overcome resistance or to be empowered to act on understanding.

Rather than avoiding conflict, reflection offers a focus as well as an opportunity to become more self-aware of the contradictions that exist between our personal visions for practice, or how we would like to practice, and the way we actually do. All health professionals reading this chapter, I suspect, will have their own personal knowledge and vision for practice and would, if they had the opportunity or the resources, want to work in that particular way. I would suggest that clinical supervision might be a way of not just testing your commitment to the process of reflection, but more importantly of begining to validate your own vision for practice.

The process of reflection has been linked to reducing the metaphorical gaps between theoretical and personal (or intuitive) knowledge and producing insights useful to an individual’s practice. However, paradoxically, the notion of intentionally identifying or producing gaps in practice has been used to encourage reflective thinking. For instance, Teekman (2000) found that the theoretical setting of situational gaps (e.g. comparing and contrasting phenomena, recognizing patterns, categorizing perceptions or reframing situations about clinical practice) led to self-questioning to create further meaning and understandings.

Although there are many different types of reflection, two most commonly known are reflection-in-practice and reflection-on-practice (Schon 1991).

Reflection-in-practice occurs while events are unfolding in which the health professional observes what is happening in practice and intervenes and makes adjustments in a reasoned way in the midst of the action.

Reflection-in-practice occurs while events are unfolding in which the health professional observes what is happening in practice and intervenes and makes adjustments in a reasoned way in the midst of the action.

An example of this might be dealing with an emergency admission to a mental health unit where the person has presented in a disturbed state and is unwilling to stay in hospital. In this situation an experienced health professional simply deals with the situation, drawing on all their professional expertise (such as de-escalating techniques, using skilful interpersonal communication while at the same time observing for the safety of those in the immediate vicinity as well as the service user). All this time the health professional may not be aware of all the interventions used and why, provided the situation resolves itself.

At a point later they might revisit the situation and reflect on action. Therefore reflection-on-practice occurs after the event and is retrospective.

At a point later they might revisit the situation and reflect on action. Therefore reflection-on-practice occurs after the event and is retrospective.

Although two common types of reflection have been described, I would suggest that there is also a third type of reflection in that it is possible to reflect on a situation before an event happens in order to rehearse it. Here I might include discussing with a senior colleague a situation that has yet to be faced; an obvious example would be going for an interview for promotion.

While no one type of reflection is posited as any better than another, the most common type of reflection practised in both the educational setting and in practice is reflection-on-practice. The sequential stages (Box 2.1) would seem to offer a ‘what’ and ‘how’ for the process of reflection as well as ‘why’ engaging in reflection supports the work of the health professional. A summary of the key elements of the processes of reflection is contained in Box 2.2.

WHAT ARE SOME OF THE CONDITIONS AND CONSEQUENCES OF BECOMING A REFLECTIVE LEARNER IN PRACTICE?

As previously stated, for the qualified healthcare professional working in practice, unlike the student in education, there is usually an element of choice — engaging in reflection or not.

In addition to choice, there obviously needs to be a commitment and a desire to ask questions about one’s self and the way practice is carried out, particularly as a response to something that was puzzling or surprised you in practice.

For some, the process of reflecting on their practice, despite it seeming to be a good idea, might not fit in easily with their own learning style and can manifest itself as passive resistance, e.g. being too busy, or not being able to find the time. (One of the ways in which you might make reflection easier to accept is to consider yourself working as a co-learner with others in a peer group. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 8.)

For some, the process of reflecting on their practice, despite it seeming to be a good idea, might not fit in easily with their own learning style and can manifest itself as passive resistance, e.g. being too busy, or not being able to find the time. (One of the ways in which you might make reflection easier to accept is to consider yourself working as a co-learner with others in a peer group. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 8.)

One of the common concerns about reflective practice and clinical supervision is about the possibility of publically exposing your thoughts and ideas and perhaps your vulnerabilities as a health professional. I again think of students who have had poor or ‘unsafe’ experiences in reflective practice:

One of the common concerns about reflective practice and clinical supervision is about the possibility of publically exposing your thoughts and ideas and perhaps your vulnerabilities as a health professional. I again think of students who have had poor or ‘unsafe’ experiences in reflective practice:

the breaking of confidentiality, albeit unintentionally, or having felt humiliated by others in recounting their practice stories. Although such cases might be isolated incidents (in most cases a learning contract would have been drawn up), such experiences can tarnish getting going at all with reflective practice.

the breaking of confidentiality, albeit unintentionally, or having felt humiliated by others in recounting their practice stories. Although such cases might be isolated incidents (in most cases a learning contract would have been drawn up), such experiences can tarnish getting going at all with reflective practice.

Another concern, related to clinical supervision, is that specific elements of practice that have been reflected upon and documented might then constitute a form of organizational surveillance (Cotton 2001, Gilbert 2001) by making the health professional’s clinical practice more visible.

Another concern, related to clinical supervision, is that specific elements of practice that have been reflected upon and documented might then constitute a form of organizational surveillance (Cotton 2001, Gilbert 2001) by making the health professional’s clinical practice more visible.

In my experience of facilitating formalized reflective practice, as well as being in a reflective group myself, health professionals often gain by considering from the outset some of the benefits and challenges (Box 2.3) posed in becoming a reflective practitioner before then embarking on the reflective journey.

While it is perhaps transforming to learn from and challenge the way we act in practice, unlearning what routinely we have been doing requires practical support as well as courage. More than likely further support will be required to cope with the new challenges presented by re-viewing or pre-viewing clinical practice through a reflective lens.

There is a risk that, by producing lists of skills and attributes necessary to become reflective, readers can become, at best, bored with reading them or, at worst, develop an overwhelming sense that they will never be able to acquire the skills and attributes listed. Often the best thing is to simply have a go! As one of the forefathers of reflective practice, John Dewey (1929), succinctly stated:

HOW MIGHT I INCORPORATE SOME OF THE IDEAS OF REFLECTIVE PRACTICE INTO A CLINICAL SUPERVISION SITUATION?

At this point of the chapter it is time to begin to examine how reflective practice might intersect with clinical supervision. While I accept that not all reflective practice is clinical supervision, I do think that all clinical supervision is to a greater or lesser extent reflective practice. Both have as their central intentions an action focus towards either improving or developing the individual health professional and, in turn, clinical practice within an environment that is both challenging and supporting. Of course, in clinical supervision, reflection is usually guided either by peers or, in an ideal situation, a supervisor who has been selected by the supervisee. By its nature, clinical supervision is usually entered into on a voluntary basis, indicating at least a potential for committing to the process of reflection. With this in mind I offer the following (Box 2.4) as being some of the ways in which the process of reflection can be incorporated into the clinical supervision encounter. You might decide that some items should be excluded or other items added.

Value yourself enough to take regular time out to reflect on practice

For most of you reading this, I suspect that at some point you have had an opportunity to engage in some form of reflection whether in an educational setting or simply as a response to events in practice that stopped you in your tracks and made you think. For some of you the idea of reflecting on practice in practice might be something you would choose to avoid! — but perhaps it might be worth considering two obvious questions:

Why do you think it might be important to take regular time out away from practice to reconsider selected aspects of the work you have been doing?

Why do you think it might be important to take regular time out away from practice to reconsider selected aspects of the work you have been doing?

What might be the consequences for yourself of not doing so?

What might be the consequences for yourself of not doing so?

Going back to the swampy lowlands of practice described earlier in the chapter — you perceive apparent contradictions between theory and practice in what you are doing and would like to have some time to reflect about them, but your workload does not allow you to do so. Now ask the questions:

Why do you think it might be important to take regular time out away from practice to reconsider the contradictions you have identified in your practice?

Why do you think it might be important to take regular time out away from practice to reconsider the contradictions you have identified in your practice?

What might be the consequences for yourself of not doing so?

What might be the consequences for yourself of not doing so?

Inevitably tensions arise, one of which will likely be between finding the time for reflective practice and ‘getting the job done’ (Eltringham et al 2000). Gilbert (2001) refers to this as working in a culture of ‘selfless obligation’ in which staff needs are a lower priority than service-user needs.

Another tension may arise between those who embrace change and those who prefer the status quo. Despite the potential of reflective practice to advance practice, its use is resisted by some. Mantzoukas and Jasper (2004) argue, powerfully, that the conscious raising of issues, by the act of reflecting on clinical practice, might bring about the need to re-order that practice and this is likely to present a threat to the equilibrium of ward life and encourage efforts to discredit reflection as a valid activity.

As you evaluate the concept of reflective practice, it would be interesting to get your response to an uncomfortable question posed by Hall and Davis (1999): is it ethical to practise without engaging in reflective practice?

Find someone you feel comfortable with to support you in your practice

Despite the challenges presented in becoming a reflective practitioner in practice, I continually find it amazing how resourceful health professionals become if they value the process enough to actively seek it out.

It is essential to find a clinical supervisor to help guide your reflective activities. (Clinical supervision is often referred to as guided structured reflection and in some cases clinical supervision policy is also referred to as protected reflective practice (Greenwich TPCT 2005).)

Of course reflection can also be a solitary activity (I suspect many of you may relate to this as you are (or were) students on a course that requires the keeping of a reflective diary or portfolio of events) but even though individuals might be committed to learning from reflection and feel they can do so effectively on their own, there are benefits in working with a clinical supervisor. The clinical supervisor can provide:

a focus for thoughts which might otherwise remain just a collection of confusing ideas;

a focus for thoughts which might otherwise remain just a collection of confusing ideas;

continuity in the form of some follow-up (as in the next meeting) as otherwise reflections might easily be forgotten;

continuity in the form of some follow-up (as in the next meeting) as otherwise reflections might easily be forgotten;

reminders that reflection is also about being response-able — there is commitment to action;

reminders that reflection is also about being response-able — there is commitment to action;

It is also worth mentioning here that where reflection is not specifically clinical supervision, the person supporting your reflections, perhaps a bit confusingly, might be a mentor, practice-based assessor, critical companion, preceptor or even your manager.

The elements of the clinical supervisory relationship are outlined in more detail in Chapter 4, but it is probably useful to offer a rationale for having someone, or a group, to guide and support your reflections on practice. Maddison (2004) suggests that without active support, students may become stuck within the reflective sequence (Box 2.1) and, therefore, there might be a significant loss of potential learning and opportunity for change. I also seem to remember reading the phrase paralysis by analysis, which aptly describes the situation in which there is plenty of thinking time in reflection but no forward movement! A key element of facilitating reflection is managing the balance between challenge and support.

In clinical supervision, where qualified health professionals disclose elements of clinical practice, too much challenge might be viewed as punitive, while too much support might be viewed as collusion. The whole point about facilitating reflection in clinical supervision is to aid practice improvement by helping supervisees to become more consciously aware of their practice. Often the situations being reflected upon are complex and in these cases facilitating reflection is brought about by actively listening and offering some feedback. This helps supervisees to reframe their thoughts or gain fresh perspectives that enable them to make more informed decisions about the situations they find themselves in.

Based on the work of Johns (2000:52), estimating the amount of guidance needed by the supervisee might also be a valuable reference point, for both the supervisor and supervisee, in evaluating the effectiveness of their efforts in the process of reflection (Box 2.5).

Identify pertinent practice stories to reflect upon

John Launer (2003:93) defines clinical supervision as:

… an opportunity for a professional to change a story about a working encounter by holding a conversation with another professional …

It might be interesting to note that John Launer is a UK general medical practitioner who promotes a narrative-based approach in primary care supervision with his colleagues. Of course the whole point of the story in clinical supervision is to invite change and it seems entirely suitable at this stage in the discussion for us to examine just what might be appropriate sorts of stories to reflect upon.

Using a story metaphor reminds me of how odd I think it is that on buying a new book some people like to go straight to the back page to see how the story ends. Perhaps it is just as odd for someone who comes into a clinical supervision session to reflect on an end-point already reached. Clinical supervisors who have already drawn conclusions before the stories have been told must be regarded with suspicion and supervisees who offer the same old familiar stories might be regarded as having not entirely prepared for the reflective sessions.

Either way, the ability of supervisees to recall a practice story, I would suggest, is an important supervisee skill and the active element of reflecting on practice with another person(s). The clinical supervisor pays attention to the story, being careful not to get too wrapped up in the content. The essence of any good story is in how it is told; the clinical supervisor then helps the supervisee to derive meaning and see the bigger issues that emerge from it.

Although many of the things I hear in clinical supervision are ‘concerns’, it is an interesting and sometimes a more challenging proposition to recount positive experiences. Clinical supervision can become a very negative experience and only serve to demoralize the supervisee if the focus is always on the downside of practice. It can be quite enlightening to recall something that you were pleased about. The focus can then change to become: ‘in what way did you think this went well?’ Exploring why something was successful can be a major source of learning as the supervisee begins to understand the answer to the question and tries to repeat the good practice.

An essential skill for the supervisee is in deciding which stories are important. This is not always straightforward, for a number of reasons:

Not making a note of significant things that have happened in practice since the last clinical supervision session.

Not making a note of significant things that have happened in practice since the last clinical supervision session.

Selectively or genuinely being unable to remember the situation as it happened some time ago.

Selectively or genuinely being unable to remember the situation as it happened some time ago.

Using informal chats in practice as a substitute for clinical supervision.

Using informal chats in practice as a substitute for clinical supervision.

Not being used to reflecting on practice with others in any depth.

Not being used to reflecting on practice with others in any depth.

Not realizing that a particular story is worth exploring.

Not realizing that a particular story is worth exploring.

Being unwilling or anxious about exposing a particular aspect of clinical practice.

Being unwilling or anxious about exposing a particular aspect of clinical practice.

Many of the above can occur when you don’t give yourself enough preparation time between clinical supervision sessions. Sometimes this preparation will need to be done away from the pressured work environment. Inadequate preparation will mean that a large proportion of clinical supervision time is spent mulling over past events, which can become tiresome and be difficult for either party to sustain for any length of time. Clinical supervision time might be better spent if you have already given some thought to different ways of developing issues that have emerged. In this way the process will inform and enhance your clinical practice.

Keeping a written record, rather than simply a mental note, of issues that crop up in your practice can be useful and need not be time-consuming. It could simply take the form of a collection of ‘tabloid newspaper banner headlines’ that you compile in practice to remind yourself of what went on.

This was how I initially organized my own reflections and the activity of thinking about what headline to match the story helped reinforce my memory of it, and helped me identify what was important about the practice incident to take with me to a clinical supervision session. This sort of written record with a banner headline and a write-up of what happened, with a space down the right-hand page to pull out key elements for further analysis, was my way of keeping a reflective journal.

For others, the act of writing rather than verbalizing what was going on might be very different. Many policies on clinical supervision now contain formats that include a reflective structure and possible content offering guidelines for those new to reflecting on practice but these can be contentious in respect to confidentiality and who has access to them. Very readable ideas about reflective writing and the keeping of journals can be found in Bolton (2005), Moon (2004), Jasper (2003), Rolfe et al (2001), and Taylor (2005). Reflective frameworks can also be a way of beginning to not just think but write reflectively and are discussed later.

Those of you new to reflection or clinical supervision, or who are unsure about what might be an appropriate issue to take to clinical supervision (which is very unlikely), could consider completing, at the end of your practice day, some of the sentences in Box 2.6.

Use a reflective framework to get you started

As Bulman (2004:165) wryly considers, although you might be filled with enthusiasm to begin the reflective journey, the dilemma of just where to start is common. Many reflective frameworks are based on stages of the reflective process (Dennison & Kirk 1990, Driscoll 1994, Ghaye & Lillyman 1997, Gibbs 1988, Rolfe et al 2001), differing levels of reflection (Goodman 1984, Mezirow 1981), student experiences (Stephenson 2000) or forms of knowledge for practice (Johns 2005). While the use of reflective frameworks can be a useful way to get started, they might also limit more creative thinking by just adhering to a reflective recipe of key questions. Not surprisingly, as Burton (2000) notes, for more experienced practitioners following a structure for reflection can also be frustratingly prescriptive.

Despite this, in my view, and based on feedback from a number of health professionals new to the idea of formally reflecting on practice, questioning is a key that can open a door to altered perspectives for practice. For me, the keys to reflection and expanding oneself and practice in clinical supervision are:

exploring answers to those questions in the context of clinical practice,

exploring answers to those questions in the context of clinical practice,

witnessing new understandings, and

witnessing new understandings, and

working with the supervisee in a dynamic movement towards actively applying the learning that has (or is) taking place.

working with the supervisee in a dynamic movement towards actively applying the learning that has (or is) taking place.

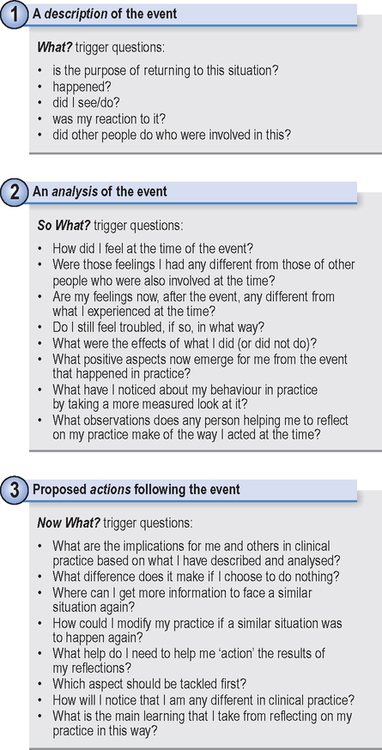

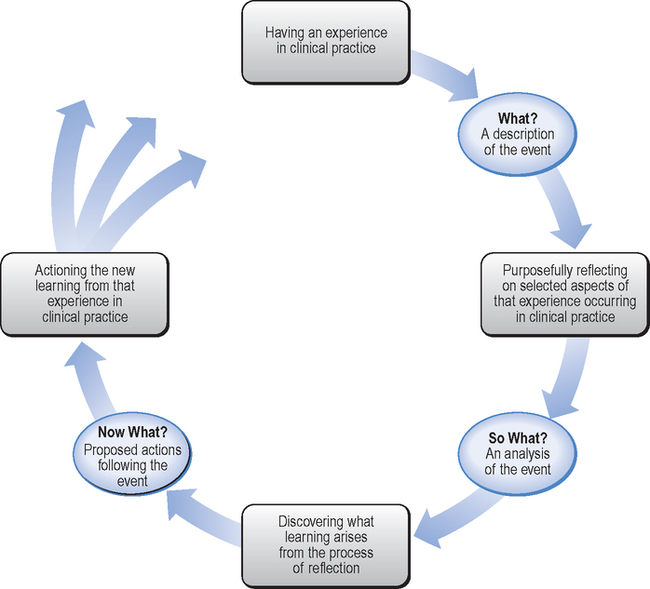

It is interesting to consider how the What? Model of Structured Reflection (Driscoll 1994) came to be through many lengthy discussions between myself and Ian Clift, a student colleague of mine undergoing teacher training. We were influenced by reflective teaching methods and a number of theorists in experiential learning who included Boud et al (1985), Dennison & Kirk (1990) and Kolb (1984). I recall one of our assignments was exploring the use of questioning and we were searching for key headings that represented the reflective cycle. We were stuck on the action element when Ian just said ‘how about — now what’? From this, the What? Model of Structured Reflection evolved and, as they say, the rest is history.

What was fascinating and also rather embarrassing was almost seven years later to find that the What–So What–Now What question headings had previously been utilized by Terry Borton (1970) as part of an experiential curriculum development initiative in schools in the USA. (Of course, this was unbeknown to me some twenty-four years earlier!) From those early beginnings, these key headings have not only been used, but also, I am glad to say, continue to be developed by other authors in clinical supervision and reflective practice (Bond & Holland 1998, Rolfe et al 2001).

For my part, the intention was (and still is) to offer a pragmatic approach to reflection for those new to the concept; although I am now more influenced by action-based approaches to clinical supervision through my interest in coaching (this is outlined in another chapter).

It might be argued that in an effort to influence action or outcome the other components of the reflective process(es) (including description, emotional content and analyses) become overlooked or not seen as important. I hope that this is not the case in my supervisory work but I will need to bear this in mind, and urge those using the What? Model of Structured Reflection to do the same (Figures 2.2 and 2.3).

Johns’s (2005) model of structured reflection (Box 2.7) seems to fit clinical practice because it has been developed and validated in practice. Attempts to fit clinical practice into other models of reflection may be less successful because structured reflection is such a complex and still not fully understood method of learning.

Perhaps you might wish to explore this for yourself in your own clinical supervision and experiment with the range of frameworks or even develop one for yourself.

PULLING IT ALL TOGETHER: IS SUPPORTED REFLECTIVE LEARNING THE ESSENCE OF CLINICAL SUPERVISION?

Clinical supervision would seem to give health professionals a legitimate opportunity to regularly stop and think in the midst of practice, with the intention of enhancing what already goes on in clinical practice. If actions occur by a supervisee as a result of guided reflection-on-practice with a clinical supervisor, or in a group situation, then clinical supervision through reflective practice may well be able to transform whole areas of clinical practice. While I readily accept that not all reflective practice is clinical supervision, I find it difficult to believe that it is possible to go about any form of clinical supervision without stimulating some sort of reflection or utilizing it as a reflective learning opportunity.

Fundamental elements of reflective clinical supervision are the develo pment of skills and a demonstrable commitment by all parties to regularly work in this way. It is likely that the facilitator, guide or clinical supervisor not only would have first-hand experience of the process but also would have the skills, attributes and the confidence to guide the clinical supervision effectively. I would suspect that, in theory anyway, there already is a growing critical mass of individuals who might be more than happy to fulfil this role or are already doing so whether as supervisees or supervisors.

What if, as some authors suggest (Fowler & Chevannes 1998, Clo uder & Sellars 2004), some health professionals do not wish to work in this way in clinical supervision or struggle with reflection, or have had less than positive experiences of working reflectively? And what of the newly qualified health professionals who want someone to ‘really’ supervise them, in the literal sense of the word, rather than engage in the hard work of reflection and self-development? What then?

Isn’t clinical supervision also about feeling comfortable with the method and having a degree of choice? From an implementation perspective, what would be likely to happen if a method of reflection was imposed as clinical supervision? What if the thought of additional transformation, with so much change already happening in healthcare, is seen as likely to upset the equilibrium of healthcare delivery?

Transforming clinical practice through reflection is work in progress, not yet an everyday activity, but the number of health professionals learning to learn in this way is growing. While it might be liberating to learn from and alter the way we think and act in practice, unlearning what we have routinely been doing will require organizational as well as practical support. Therefore, it is important that all echelons of healthcare organizations have a collaborative vision for clinical practice and a belief that learning is a continuing process throughout a professional’s life; as important at the top as at the lower end of of any healthcare organization.

The actions of senior staff in supporting practitioners who wish to be actively engaged in clinical supervision will be more important than the production of nicely worded policy documents. The notion of a lifelong learning culture in clinical practice, one in which there is freedom to learn and an openness to share first-hand experiences through reflection and clinical supervision as well as do the work, I would suggest, is the longer-term goal for any modern healthcare organization and legitimized by clinical governance. I wonder what might be the implications for you, the reader, in your own practice if such a goal were to be achieved?

Figure 2.1 is a Dalmatian dog!