Adventures in facilitating group clinical supervision in practice

INTRODUCTION

The metaphor in the title of the chapter of having an ‘adventure’ in group supervision, or any form of clinical supervision for that matter, is intended to evoke the idea in (or perhaps even give permission to) health professionals that participating in group supervision can enable collaborative explorations of practice, an opportunity for treading new paths, as well as the likelihood of experiencing some surprises during the process of the group clinical supervision journey. Many of the ideas for this chapter stem from my own experiences of being a supervisee in group supervision, as well as being a facilitator of groups that included group supervision. As a non-therapist, I refer to the term ‘facilitator’ (of learning) throughout the chapter as opposed to group supervisor, although the terms do seem to be interchangeable in the clinical supervision literature.

On the surface, the potential for collaboratively working in a group way in clinical supervision would seem to be entirely appropriate to consider in the wider organizational sense, given the current healthcare climate for change and reform. However it is worth reflecting on the implications of legitimizing the development of groups in practice that are likely to be microcosms of the wider organization, particularly with the development of multiprofessional clinical supervision groups (Hyrkas & Appelqvist-Schmlechner 2003, Mullarkey et al 2001). It is highly likely and even ‘normal’ to expect conflicts and uncertainties to emerge as part of the process of having regular and formalized group discussions that are intended to improve practice. The outcomes of such discussions may present even more conflict as health professionals either enable improvements or become disabled by the attempts of individuals determined to maintain the status quo — individuals who only appear to rather than actively support the principles of group clinical supervision. For instance, while health professionals, if given the opportunity, would like to implement group supervision as a highly valued method (Butterworth et al 1997), heavy workloads, busy schedules and staff shortages frequently mean that the activity is often not given organizational priority (Hyrkas et al 2002, Sellars 2004, Walsh et al 2003). It requires not only commitment but also creativity to ensure that the development of group supervision activities and approaches are not disrupted.

I am particularly mindful that, for some, the idea of working in a group way can conjure up notions of a being in a form of ‘pseudo-therapy’ (Yegdich 1999) in unskilled or inexperienced hands. Perhaps this is not surprising as much of the UK clinical supervision literature in the health professions has been, and continues to be, influenced by counselling and psychotherapy frameworks. An obvious difference, to me, between group supervision and therapy is that in the former the focus of concern is usually external to the individual (e.g. clinical practice) and in the latter it is internal to the individual (e.g. personality, relieving symptoms). Therefore, I would suggest for those new to group working that the emphasis be on the health professionals’ work and primarily the ‘here and now’ but with prominence also given to ‘future’ practice(s). Perhaps much easier to say than do!

In tandem with this are questions raised about the ‘appropriateness’ (Malin 2000, Rudd & Wolsey 1997) of utilizing therapy-orientated approaches for clinical supervision in acute healthcare environments. A belief that they are inappropriate may also pose a barrier to ‘getting started’.

In this chapter, while accepting that there are numerous other approaches that can be adapted for group clinical supervision, I will focus on action learning, Balint and peer group working as workable alternatives to the perceived inappropriate models found in psychological literature. That said, the knowledge derived from psychological research is invaluable; here I have used examples from psychological literature to outline stages of group development and facilitator styles, and Graham Sloan in his chapter discusses the dynamics of groups from a psychological perspective, suggesting that understanding group behaviour might enable the aquisition of protective mechanisms by those feeling vulnerable because they are new to, or are considering setting up, a group situation in practice.

WORKING IN A GROUP WAY TOWARDS CLINICAL SUPERVISION

It might seem strange to even consider working in a group way in clinical supervision when all of you reading this will already have had experience of group working in one way or another, in your personal as well as work lives. But this is the nature of improving practice through reflective practice (described in an earlier chapter); intentionally looking more critically at your routine and taken-for-granted activities can ultimately transform them. I would not be surprised to find that, based on your experiences, you already have some ideas about what might constitute effective and not so effective group clinical supervision and this will ultimately affect your decision to become engaged in the process (or not).

Perhaps some of your ideas about an effective group might have centred on things like members of the group being clear about what is supposed to happen in the group and having some idea of roles and responsibilities, the atmosphere being relaxed, the group being one in which everyone was able to express an opinion and one in which you felt personally valued. On the other hand, you might see an ineffective group as one over-dominated by certain members’ opinions, where disagreements make you feel uncomfortable and, because of its poor structure, in which very little seems to be achieved.

Having, as well as expressing, an idea of what some of your hopes, fears and expectations of working in groups are is an essential part of establishing agreement in a clinical supervision group and is discussed in more detail later in the chapter.

I suspect that even if we were able to just get ten readers’ responses to the above exercise in their group situations we would be likely to find that:

their own world views and experiences of working in groups were different;

their own world views and experiences of working in groups were different;

each might initially consider their own views as being right for taking forward into the development of group clinical supervision.

each might initially consider their own views as being right for taking forward into the development of group clinical supervision.

Of course, if, in those groups you previously thought about, a spirit of collaboration was encouraged and there was a willingness to arrive at mutually agreed outcomes for group working, despite different points of view, people would be more likely to go away satisfied that their point of view had at least been taken into consideration. However, there are likely to be times when the spirit is unwilling and the need to be right and the need for everyone else to agree that you are right will get in the way of achieving any outcome at all. While diversity in opinion should be welcomed as a source of strength in a group, it can be a challenge to deal with! Alternatively, both of the rather polarized scenarios outlined above, while seeming to present stark differences in group behaviours that may or may not have directly affected you, might also be indicators of quite ‘normal’ stages in the development of working in groups (rather than being anything sinister).

Numerous models for stages of group development exist, but probably one of the best known and easily understood is by Bruce Tuckman (1965) — revised with Mary Ann Jensen (Tuckman & Jensen 1977). The work was based on looking at the behaviour of small groups and recognizing they went through distinct phases over their lifetimes (Figure 8.1). It has also become part of a web-based working guide for modernizing UK healthcare (NHS Modernization Agency 2006).

In relation to clinical supervision, being aware of the different stages of group development is useful not only to a facilitator but also to the participants who can see whether they are realizing their expected potential or not.

Like a living organism, a group will necessarily change and reform and shift into a different developmental stage; e.g. a group that is happily Norming or Performing might move to a different stage of development by the addition (or loss) of participants. It is not always what happens to a group but the way that the ‘happening’ is dealt with by the group that gives a clue to its stage of development.

A metaphor for capturing the different stages of group life, which I often use, is described by Christine Hogan (2003:99). She depicts the stages of group life as not being dissimilar to the four seasons:

Winter (the stage of defensiveness),

Winter (the stage of defensiveness),

Spring (the stage of working through defensiveness),

Spring (the stage of working through defensiveness),

The implication for any model you choose to use (if indeed you do) is that the stage the group is in influences other stages, and, in particular, the group’s ability to perform to its maximum potential. It also seems useful, as either a participant or facilitator, to have a working knowledge of the different stages of group development, as any individual or group interventions will need to take into account the level of group functioning based on its stage of development.

So, in summary, to understand the complexities of the functioning of any group, it is helpful to have an awareness of:

Thinking again about your previous and current involvement in groups, e.g. at work and in educational settings, there will be many benefits as well a number of challenges to consider for undertaking working in a group way in clinical supervision. You might wish to compare your ideas with the contents of Table 8.1.

TABLE 8.1

Some benefits and challenges for working in a group way at work or in the educational setting

| Benefits of working in a group way | Challenges of working in a group way |

| A diversity of opinion can be expressed | Issues or concerns raised can seem to go off at a tangent and lack focus |

| Feelings of an increased sense of support by realizing others have similar concerns | Not everyone will be suited to working in a group way, e.g. feelings of vulnerability |

| Listening to others concerns can be personally valuable in your own situation | Individual feelings of pressure to conform to a particular way of thinking and not ‘rock the boat’ |

| More transparency about what happens in a group | Inner conflicts or feelings can be masked and not addressed |

| An additional way of personally learning and developing through sharing experiences | Concerns about where individual issues raised might go after the group ends |

| More cost-effective in time and resources to get things done | Lack of time to deal with an issue or concern in any depth |

| Able to obtain feedback from others about issues or concerns raised | The dynamics of the group can sometimes make individuals feel uncomfortable |

| Increased possibilities to share decision-making and responsibilities | The group can sometimes seem to end up as a ‘talking shop’ with very little being achieved |

| Being part of a group can lead to deeper friendships being realized | Can be difficult to know everyone and follow through on issues with a fluctuating membership |

Having raised some awareness about working in groups generally, it might now become easier to make more informed decisions about the development of your own group clinical supervision in particular.

Working in a group way in clinical supervision, as opposed to self-reflecting on practice, allows practice to be viewed through a ‘getting some feedback’ lens. The more people in the group, the more potential for feedback! However, too large a group could have drawbacks. Although I interpret ‘group’ as having at least three participants, the number of participants considered necessary in a group clinical supervision situation remains open to debate. An optimal number seems to rest between five and eight participants, but will be dependent on the amount of time available and the experience of a facilitator/group clinical supervisor.

Despite the challenges posed by group working and the different dynamics that come into play, Butterworth and colleagues (1997) in their national UK study found group clinical supervision to be the preferred option. A number of other authors cite more specific benefits for health professionals becoming engaged in group clinical supervision:

Reduced professional isolation through increased collaboration between departments (Ashburner et al 2004, Bedward & Daniels 2005).

Reduced professional isolation through increased collaboration between departments (Ashburner et al 2004, Bedward & Daniels 2005).

A safe environment where health professionals can discuss their limitations and problems without criticism (Dudley & Butterworth 1994).

A safe environment where health professionals can discuss their limitations and problems without criticism (Dudley & Butterworth 1994).

A way of containing anxiety through increased self-awareness and professional identity (Arvidsson et al 2001, Jones 2003, Lindahl & Norberg 2002).

A way of containing anxiety through increased self-awareness and professional identity (Arvidsson et al 2001, Jones 2003, Lindahl & Norberg 2002).

Increased courage to act more confidently and competently in practice (Arvidsson et al 2000, Landmark et al 2004).

Increased courage to act more confidently and competently in practice (Arvidsson et al 2000, Landmark et al 2004).

More positive relationships with patients (Severinsson 1995).

More positive relationships with patients (Severinsson 1995).

Reduced feelings of stress as more able to manage challenging circumstances in practice (Begat et al 1997, Butterworth 1996, Butterworth et al 1997, Severinsson & Borgenhammar 1997, Williamson & Dodds 1999).

Reduced feelings of stress as more able to manage challenging circumstances in practice (Begat et al 1997, Butterworth 1996, Butterworth et al 1997, Severinsson & Borgenhammar 1997, Williamson & Dodds 1999).

Increased job satisfaction (Berg et al 1994, Butterworth et al 1997).

Increased job satisfaction (Berg et al 1994, Butterworth et al 1997).

Lower sickness rates (Ashburner et al 2004).

Lower sickness rates (Ashburner et al 2004).

Retaining the strength and energy to carry on in practice (Arvidsson et al 2001).

Retaining the strength and energy to carry on in practice (Arvidsson et al 2001).

Improved team communication (Hyrkas & Appelqvist-Schmidlechner 2003, Malin 2000).

Improved team communication (Hyrkas & Appelqvist-Schmidlechner 2003, Malin 2000).

A reduction in doubting one’s ability to act in practice (Hyrkas et al 2002).

A reduction in doubting one’s ability to act in practice (Hyrkas et al 2002).

Based on your particular circumstances, you might consider group supervision to be a preferred option (e.g. in terms of the logistics, the prevailing economic conditions and your wish to inspire collaborative working, you may well consider it to be a sensible choice). However, what can present as a solution for one person in the development of clinical supervision in practice, might present as a difficult challenge to another. The clear message is that a choice of suitable clinical supervision formats (e.g. one-to-one situation, group setting) must be available. And keeping in mind that choosing confers a sense of ownership of the thing chosen, choice is a critical factor in the successful implementation of any workable scheme in practice (and described in more detail in the next chapter).

GROUP SUPERVISION APPROACHES

Decisions to commence group clinical supervision will obviously need to be discussed beforehand and it might also be worth dipping into the next chapter on implementing clinical supervision to give you an idea of ways of approaching the matter with staff colleagues. Key questions will be:

is the group to be an ‘open’ (fluctuating staff member attendance) or a ‘closed’ (limited staff membership) group?

is the group to be an ‘open’ (fluctuating staff member attendance) or a ‘closed’ (limited staff membership) group?

Hyrkas and colleagues (2002) describe team supervision as an activity that involves members from differing professional backgrounds but others would refer to this as multiprofessional group supervision as opposed to single professional group supervision (Mullarkey et al 2001). However you refer to it, the group will need to decide what kind of facilitation/supervision should prevail, as there are a number of possibilities:

Single professional group supervision facilitated by a supervisor from the same discipline, e.g. senior occupational therapist to occupational therapists.

Single professional group supervision facilitated by a supervisor from the same discipline, e.g. senior occupational therapist to occupational therapists.

Single professional group supervision facilitated by a supervisor from a different discipline, e.g. a group of specialist nurses and a counsellor.

Single professional group supervision facilitated by a supervisor from a different discipline, e.g. a group of specialist nurses and a counsellor.

Multiprofessional (team) group supervision facilitated by a designated supervisor, e.g. nominated or a rotating supervisor from within the team.

Multiprofessional (team) group supervision facilitated by a designated supervisor, e.g. nominated or a rotating supervisor from within the team.

Group supervision facilitated by a supervisor external to the organization, e.g. a team of general practitioners from the same practice supervised by a psychotherapist.

Group supervision facilitated by a supervisor external to the organization, e.g. a team of general practitioners from the same practice supervised by a psychotherapist.

Supervision by professionals from a similar discipline or background or expertise who do not work together on a regular basis, e.g. as part of a regular networking event.

Supervision by professionals from a similar discipline or background or expertise who do not work together on a regular basis, e.g. as part of a regular networking event.

Not all formats of group clinical supervision require the same degree of skill in the processes of group work. There are numerous options for ways of working in groups and more specific attention to psychological approaches in clinical supervision is offered in a previous chapter. Proctor (2000:38), based on the original work of Inskipp and Proctor (1995), suggests four types of group clinical supervision in which the supervisory role can vary from being ‘in control’ of the process of group supervision, through a continuum of involvement to one where supervisees take responsibility for the process themselves:

Authoritative group: the supervisor is responsible for supervising each participant in turn — supervision in a group.

Authoritative group: the supervisor is responsible for supervising each participant in turn — supervision in a group.

Participative group: The group supervisor is in charge of the supervision but invites other group members to participate and learn how to co-supervise each other — supervision with a group.

Participative group: The group supervisor is in charge of the supervision but invites other group members to participate and learn how to co-supervise each other — supervision with a group.

Co-operative group: Supervisor acts as facilitator for the group with participants sharing and actively involved in the co-supervision of each other — supervision by a group.

Co-operative group: Supervisor acts as facilitator for the group with participants sharing and actively involved in the co-supervision of each other — supervision by a group.

Peer group supervision: No permanent supervisor, participants share overall responsibility or take turns to be the facilitator.

Peer group supervision: No permanent supervisor, participants share overall responsibility or take turns to be the facilitator.

An example of an authoritative or directive approach to group clinical supervision is when the supervisor (in the truest sense of the word) is a senior manager and there a definite superior–inferior relationship between the supervisor and the supervisees. Examples of this can be found in the UK statutory requirements for child protection supervision (Department of Health 1997) for health visitors and midwives or in managerial forms of group supervision such as caseload supervision in mental health services. While the overriding functions of these forms of group supervision are to monitor, safeguard and protect vulnerable patients or minors, it is questionable whether this is truly group clinical supervision, as it seems there is little emphasis placed by the supervisor on supporting vulnerable health professionals (Davis & Cockayne 2006, Dube undated). A further example of an authoritative group is where supervisees individually reflect on significant practice incidents to the group but remain directed by the supervisor, e.g. a group of junior staff being supervised by a more senior member of staff. Such supervision groups are often characterized by the hierarchical relationship that exists between the supervisor and supervisees and the degree of group control.

Depending on the nature of the group supervision described in the first three types, the role of the supervisee/participant varies between being ‘a spectator’ (McMahon & Patton 2002:57) of somebody else’s supervision in the group, to becoming an active co-supervisor/facilitator. In my experience, it can be useful for those who have never experienced group supervision to have a more structured group supervision experience for an agreed number of meetings. As the group becomes more skilled and builds in confidence, participants/supervisees can then experiment with other types of group supervision, in which the role of the facilitator becomes less overt or directive and participants/supervisees begin to manage their own process. This could be built in as part of the contractual agreement, with regular time for reviewing group skills and shared learning, leading to a self-sustaining group for the future (discussed below).

Intentionally adopting a cascading method in group supervision offers an opportunity for an experiential and work-based learning activity as well as developing ownership of the process. In doing so, the participants/supervisees are able to gradually increase their autonomy and take charge of their own supervision through shared learning, role modelling of group supervisory ideas and experiencing hands-on facilitation. The clear message is around choices being available in clinical supervision whether in a one-to-one situation or the group setting and is a critical factor in the successful implementation of any workable scheme in practice (and described in more detail in the next chapter).

That said, I do agree wholeheartedly with Rolfe et al (2001:102) that the best, perhaps the only, way to learn about group supervision is to actually take part in a group as either a supervisee/participant or a facilitator/participant.

In my experience of facilitating groups to manage themselves in group clinical supervision, it can be helpful, even expected, to offer an initial structure for participants before getting to a stage of what Bernadette, one of my supervisees, referred to as:

While it is beyond the scope of this chapter to go into detail about the very many and varied formats of group clinical supervision, an approach that seems to embrace participative and co-operative formats of group clinical supervision, which might be used as a starting point for a group supervision activity, is a modified form of action learning (McGill & Beaty 2002, RCNI 2000) or the development of action learning groups (Graham 1995, Heidari & Galvin 2003, Platzer 2004).

While the focus of action learning sets/groups differs according to the situation and the needs of the group as a whole, I would suggest that the general principles would seem to closely align to ideas about group clinical supervision (Box 8.1).

While, in a group supervision sense, the principles of action learning will tend to focus on individuals within the group, it is most often associated with large project development. In my own experience, I have used action learning principles as a form of group supervision to help implement clinical supervision in organizations. What happens here is that the participants/supervisees in the group contract that the issues or concerns brought to group supervision specifically focus on being related to the implementation of clinical supervision. In this way, a sense of having a shared identity develops in the group (we are all implementing clinical supervision) and group members become ‘comrades in clinical supervision adversity’ (to adopt the phrase from the founder of action learning, Reg Revans (Revans 1982)). At the same time, by considering other member’s experiences, problems or issues about the implementation of clinical supervision, each group member learns from the others in the group.

Although there is no single ‘correct’ format for action learning, as the process continually evolves over time, there is a commitment, initially by the facilitator, to help individuals work on the tasks presented and avoid becoming embroiled in non-productive general discussions about issues.

Another fundamental function of a group facilitator is the enabling of group independence. The responsibility of running ‘set advising’ or facilitation should be handed over to the group itself as soon as possible to encourage participants/supervisees to become the owners of their own learning process and subsequent actions.

Other issues to consider in facilitating clinical supervision groups are as follows:

By having group participants all from the same department there is likely to be a subsequent lack of external perspective — individuals ‘not being able to see the wood for trees’

By having group participants all from the same department there is likely to be a subsequent lack of external perspective — individuals ‘not being able to see the wood for trees’

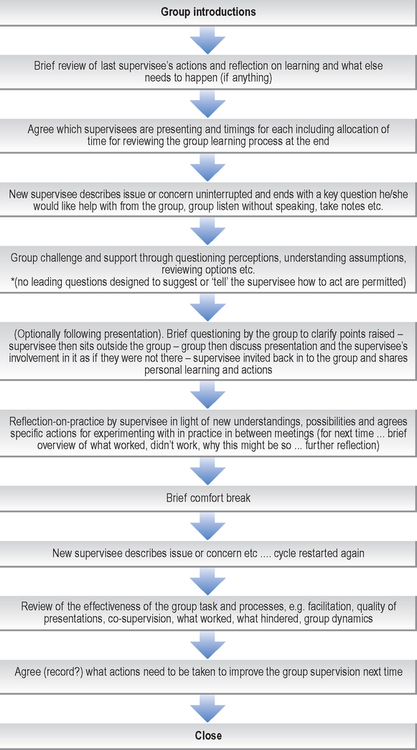

The number of group participants/supervisees will determine structure (Figure 8.2) and subsequent timings

The number of group participants/supervisees will determine structure (Figure 8.2) and subsequent timings

Further information on the principles of action learning can be found in McGill and Beaty (2002), Beaty (2003) and NATPACT (2005).

Cottrell and Smith (2000), in their excellent website resource on clinical supervision, propose a different approach to group clinical supervision based on participative co-counselling, where not only is the role of the facilitator prescribed but also a structured approach in getting started is encouraged. They warn that, depending on the stage of group development, applying structured approaches in group clinical supervision might be too restrictive but that rotating roles and building in a review of the process will benefit the leadership of the whole group.

An interesting approach, and one of the earliest methods of clinical supervision for family doctors (Horder 2001, Salinsky 2003), is the Balint Group approach (Balint 2000) established in the 1950s and named after Michael Balint (a psychoanalyst from Hungary). It has since spawned a number of international Balint Societies and websites. Although a Balint leader is trained and accredited in the method, the principles behind the Balint approach might well be applicable in certain group supervision situations. The Balint discussion groups intentionally stimulate family doctors to examine their understandings of the emotional content of the doctor–patient relationship and explore alternative ways of responding (The Balint Society 2006). The closed group discussions, less concerned with finding solutions, focus on exploring relationships (Salinsky 2003:81). The facilitator role is amply described as follows:

Presentations are spontaneous, based on priority issues from within the group, without the use of notes for around five minutes followed by composition of a key question for the group to consider. After a short period of factual, rather than feeling questions to elicit clarity, the presenter ‘pushes back’ and takes no further part in the discussion remaining an observer for around 20 minutes whilst the rest of the group discuss the question before then rejoining the group.

The facilitator is mainly concerned with the psychological group processes described by Johnson et al (2004) as:

… self reflection and exploration of meaning rather than problem solving is the key to Balint leadership … it is not the leader’s individual brilliance that illuminates the case, but the richness and diversity of the group participation and interactions he/she facilitates …

My rationale for including what is essentially medical practitioner group supervision into the discussion is that the principles might be applied to those working in more technical areas of clinical practice (such as intensive care, neonatal units, theatres, accident and emergency departments), where, more often than not, the patients are too much in need of (life) support for the staff to then get any!

As a charge nurse in intensive care in a previous life, I would have welcomed the formal support that specialist external supervisors such as mental health practitioners or chaplains might have brought to often distressing situations. As it was, my distress tended to be sorted out informally in a coffee room or over a beer afterwards and somehow just seemed to get buried — but I remember those patients and relatives, including their names, and the remembrance of the associated distress still surfaces occasionally, almost twenty years on. It seems to me that a modified Balint group approach with a supervisory eye firmly fixed on improving relationships with patients (as well as difficult staff) might be protective for both staff and patients.

The final dip into group supervisory approaches involves peer group working. In this approach there is no permanent group facilitator, with the role often being rotated between individual members of the group or members working in pairs (co-facilitation). While seemingly a straightforward option for group clinical supervision with a captured audience to hand, it can be more challenging than at first seems and it can be helpful to have an external or experienced group facilitator to begin the process. In a recent experience, while working as an external consultant to support the development of peer group supervision with senior physiotherapists, who were all of the same grade and experience, I had to pay particular attention to the structure of the meetings and the contract. Aside from the practicalities of finding the space to regularly meet as a peer group, which was challenging, I was interested to observe the behaviours displayed in this peer group supervision; behaviours that were ‘normal’ in their everyday clinical practice. For instance:

And behaviours that reflected their attitude toward being in a clinical supervision group:

While working in what are sometimes called ‘concentric circles’ (an inner working supervision group and an outer group of observers), those same taken for granted normal behaviours became glaringly obvious and significant for the observers — it became clear that there was a need for a contract regarding the conduct of the group. This demonstrates how less noticeable things are when there is a familiarity between peers working in the same culture who have developed close relationships. Playle and Mullarkey (1998) cite how the unconscious dynamics of relationships at work can often be mirrored within behaviours displayed in group clinical supervision or what they refer to as ‘parallel processing’. A possibility for ‘making the unnoticed more noticed’, in groups where a closeness exists, is to ensure (as part of the contractual agreement) that time is built into the meetings for reflection on what has happened in the group and the obtaining of sensitive ‘observer’ feedback — particularly when peer group supervision is a new process in practice.

Turner and colleagues (2005), in the development of peer group supervision as a form of networking supervision for specialist nurses, reported similar behaviours to those I had observed:

… at our first attempt to tackle a clinical issue, without prompting or guidance, the group used its usual problem solving approach. Its application in this situation meant we all wanted to talk over each other, offering advice and solutions so that the individual presenting the situation for discussion felt attacked rather than supported. The whole experience was very distressing. Our second attempt, using facilitation and guidance, enabled us to reflect upon this and then approach another scenario using new techniques, which enabled the presenter to reach their own answer/conclusion. This demonstrated a significant change to the group even in that short time.

Considering peer group clinical supervision as an option in and for practice is in itself an invitation to colleagues for increased openness, collaborative working and potential challenge as well as support.

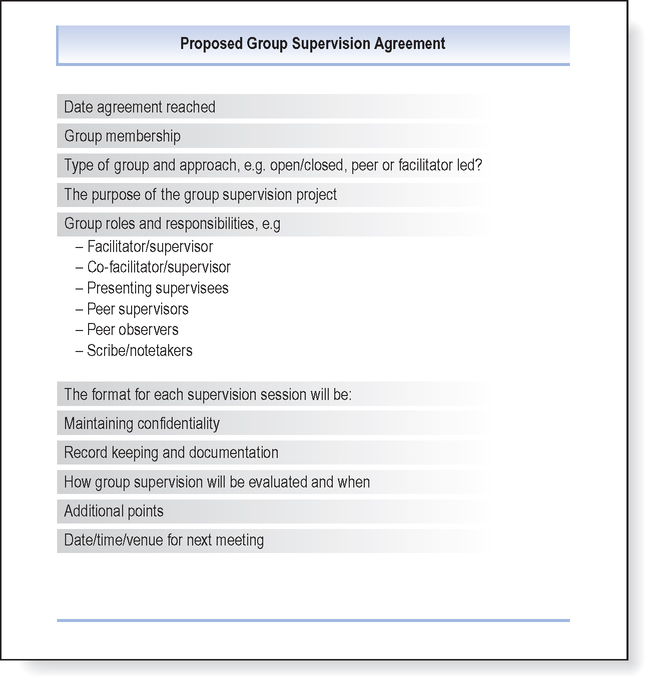

The types and possibilities for working in a group way in clinical supervision are numerous and the working style of any group is likely to alter as the group matures and increases in experience and confidence. But an initial key to any form of working in a group way in clinical supervision is to gain formal agreement on what the group’s intentions are and to make sure those intentions are clear to all participants at the outset. A previous chapter by Stephen Power has examined this in more detail, but in groups that are known to have members with conflicting views it is even more important to establish these ground-rules because if potential difficulties are not attended to, disenchantment and even abandonment altogether of the idea of having a group can ensue.

Prior to contracting for group clinical supervision in practice it will be useful to have a meeting with potential group members. You might wish to use the headings contained in Figure 8.3 as a discussion item — or circulate the headings to the group before the first meeting as a form of agenda.

It is extremely unlikely that you will be able to complete all of the items in the first meeting, but it does offer a focus for a discussion. What is important is to get an agreement for how you intend working in group supervision, and this is a useful reference point if at a later stage disagreements begin to surface. Voicing disagreement (as stated earlier in the chapter) is a normal stage of group life and an opportunity to change, rather than necessarily being a negative phenomenon. I would be concerned as a facilitator that the group might be becoming too collusive without some form of positive challenge or dissent! For instance, Walsh et al (2003) in the development of their group supervision decided on the following set of group norms:

Commitment to supervision and the group

Commitment to supervision and the group

Meetings should start and finish on time

Meetings should start and finish on time

All members to attend except where an unforeseen clinical issue places a client at risk

All members to attend except where an unforeseen clinical issue places a client at risk

Preparedness to disclose and take risks

Preparedness to disclose and take risks

Receptiveness to others’ views

Receptiveness to others’ views

Responsibility of the presenter to be prepared beforehand

Responsibility of the presenter to be prepared beforehand

Supportive critical friendship attitude

Supportive critical friendship attitude

Confidentiality with exceptions, e.g. cases where unsafe, unprofessional or potentially dangerous conduct is identified

Confidentiality with exceptions, e.g. cases where unsafe, unprofessional or potentially dangerous conduct is identified

The role of the facilitator/supervisor is a key aspect of effective group clinical supervision working in which, as we have seen, a number of different approaches can be employed. While it is very likely that a facilitator/supervisor will have had considerable experience in working with groups, some groups might be experimental, rather than experiential, particularly in a peer group situation. Therefore it is useful to get some basic ideas about the challenges and choices when facilitating group supervision for the first time, although this is not a substitute for gaining further training from within your own learning resources (e.g. through independent trainers or from your local education provider). You may already have ideas about this before commencing any group supervision project.

CHALLENGES AND CHOICES WHEN FACILITATING GROUP CLINICAL SUPERVISION

A common advertising slogan is size matters and it is certainly worth thinking about when facilitating group supervision. Within groups an absent or new participant can alter the whole group dynamic. For instance, in more structured and participative groups where differing roles are critical to the overall process, absenteeism can make a profound difference to what was intended to happen, as well as leading to concerns being raised about the commitment towards group supervision. Likewise, introducing a new person into the group is likely to alter the group dynamics back to a previous stage of development (Figure 8.1), but might also be an invigorating change to the life and workings of the group. I have known some groups to state, as part of the contracting process, that if a person misses a group on two consecutive occasions, and if apologies are not sent, they cannot return. It is therefore critical to group functioning to discuss such matters on commencing group supervision, including whether the group intends to be ‘closed’ (fixed membership) or ‘open’ (dip in and out and mixed membership). Of course, the larger the group the more complex the facilitation becomes.

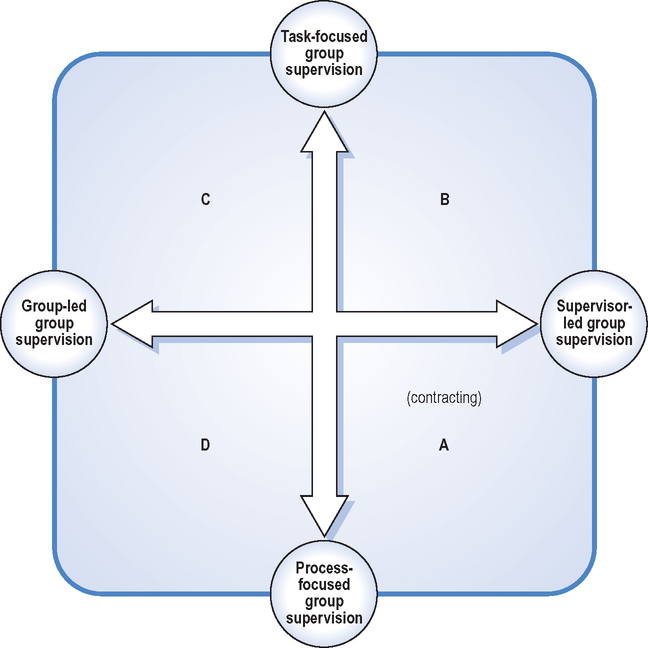

Johns (2001) wisely warned that, depending on the intent and emphasis of the supervisor, clinical supervision can be a very different experience for supervisees. What he exposed in his research was how the underlying tensions in individual supervisors’ perceptions and organizational ideas about the nature of clinical supervision will impact on the way clinical supervision is organized. This is a key consideration in working in a group way as a clinical supervisor for the first time. Hawkins and Shohet (2002:134) suggest that unless supervisees are already experienced in group work they are very likely to be influenced by the styles of their group supervisors. They outline four quadrants depicting differing styles (Figure 8.4) a group supervisor can move through with supervisees, depending on the needs of the group and the stage of group development.

Clearly it is important for all those involved in decision-making about how group supervision is organized that there is a conscious awareness that alternative group styles exist depending on the stage of group development (Figure 8.1) and the experience of the group as a whole, including the group supervisor. New group supervisors may well need to consider whether their preferred style is an intentional choice, or simply based on their own understandings and experience on what they think group clinical supervision is. I would suggest that the facilitator/supervisor role be an item of discussion right from the start with participants/supervisees when making a contractual agreement (see Figure 8.3).

The different styles, far from making choices in the group clinical supervision process even more complex, simply offer a range of opportunities for the group, as well as the intended group supervisor. While acknowledging my own bias for reflective learning in group clinical supervision, the whole process can become a shared, or co-learning, experience and an adventure in itself for the whole group, including the supervisor, provided that there are built-in opportunities for feedback, learning and subsequent improvement.

This section of the chapter is concerned with the facilitation of group clinical supervision in its widest sense; in that a group exists for the purposes of clinical supervision and that the process is overseen by a single group supervisor (facilitator), or rotating group supervisors (facilitators), or directed by the group members themselves. In all formats, I would suggest it is helpful to the group supervisor to have some sort of reference point on which to base facilitation, or as the Latin root of the word means, ‘to make it easier’ (for the group). Bens (2000:7) likens the role of a facilitator to a match referee:

… rather than being a player, a facilitator acts more like the referee. That means you watch the action, more than participate in it. You control which activities happen, keep your finger on the pulse of the game and know when to move on or wrap things up …

While I recognize that this may be an ideal, where possible, it is easier if the facilitator, like the referee, is non-partisan and detached from the hurly-burly of clinical practice. By not having an emotional attachment to the group in its everyday roles or tasks, it is much easier to observe what the group cannot see and (with permission) raise matters that the group finds difficult. Not long ago I recently facilitated a group of healthcare scientists to set up their own group supervision. Not being emotionally involved and not being very clear about their everyday work allowed me to see and name the ‘elephant in the room’ (the thing nobody knows quite what to do with because of its enormity and avoids talking about). That elephant was the reorganization of laboratories that had led to acrimonious relationships in the directorate. Once this had been identified it was unable to be ignored and the group focused on how to manage it.

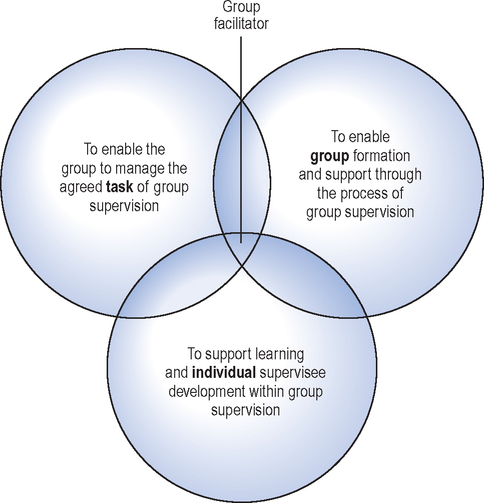

In a group supervision situation the facilitator needs to balance the responsibilities for enabling the group to manage their ‘task’ with being attentive to the group ‘process’. The task of the group supervision (or what’s happening) will be quite obvious as this would have been structured and verbally agreed in advance (e.g. two supervisees present their situations in the time allowed, with a time for feedback). The process of the group supervision (how it’s happening) relates to what is not being verbalized, is less visible and is associated with the more psychological aspects of the group (such as how the group members seem to relate to each other, the group atmosphere, feelings people are having towards each other). Rogers (2002:7) eloquently summarizes this as:

… the task concerns the head and the process concerns the heart … for effective group working, both the heads and hearts of … (group supervisees) … will need to be satisfied …

(The words in italics are mine.)

In reality, the group facilitator’s role, skills and attributes lie on a continuum from actively ‘doing for others’ (assisting the group with their specific tasks and goals) to ‘enabling those same others’ (through supportive challenge, to developing alternative ways of seeing, learning and subsequently working).

In summary, the three overlapping functions of the facilitator (Figure 8.5) are reminders that the effective facilitation of group supervision is interdependent, will not remain static and is a dynamic and ongoing process.

For instance, if the task or intentions of group supervision have not been agreed with the group from the start or not enough attention is being paid to ongoing group processes (which might not be that obvious), not only will the task of group supervision suffer, but also individual supervisees in the group will be dissatisfied. Similarly, if the individual needs of the supervisee are not being met, the group will become ineffective and the purpose of group supervision will struggle to become realized.

The challenges and choices presented by facilitating really bring home to me, in my work, that learning to become an effective facilitator is a continually ongoing process; this is the very essence of lifelong learning in clinical supervision. This is not really surprising as each group is, in a sense, unique, because of the variability of the skills and personalities of its members, and therefore the facilitator’s responses must adapt to this variability. In other words, the facilitator has to learn new ways or adapt old ways to effectively facilitate.

I state this to offer hope to new group facilitators that the work is never done and there is always room for improvement regardless of how much training or experience you have. While I think it is perfectly possible to simply run your own group supervision from scratch, it is only fair to that group that any potential facilitator has an idea of some of the more common challenges and choices posed in group working. Thinking about this, I offer a 12 point survival guide for new group facilitators in Box 8.2.

While the discussion in this chapter has tended to focus on how to get started with group clinical supervision and some thoughts on what to do while it is going on, I think it wise to now consider how to end clinical supervision even though you might just be beginning. While the process of learning as a facilitator is a lifelong adventure, there will be a time when group clinical supervision finally comes to an end or conclusion.

ENDING GROUP CLINICAL SUPERVISION (AND THE CHAPTER!)

As I think it important to consider how to draw group supervision to a conclusion, I was surprised that 275 clinical supervision articles, identified in a literature search by Chambers and Cutcliffe (2001), did not make any specific reference to issues of ending clinical supervision in their titles or key words.

Endings are significant and Chambers and Cutliffe (2001) acknowledge this when they comment that as working in groups involves an investment in time, commitment and energy it can be with some sadness as well as some joy that the work comes to an end.

Power (1999:205) cites three main reasons why clinical supervision groups might close before the work is completed:

For most clinical supervision groups I work with, for contractual reasons, there is an intended end-point set at the beginning — normally at the end of anything from six to ten sessions. I am often employed to get things started and furnish the group with the necessary tools for it to continue once I leave. In these cases, the ending is planned for as well as expected and the closing ceremony (usually with some cakes and coffee) often centres on formally reviewing achievements and deciding on what then needs to happen. At these ceremonies I often experience mixed emotions: relief that it has finished, a sense of satisfaction at the achievements made, and some sadness at having to say goodbye at that metaphorical station as the train continues on its journey without me. I am sure many group members must also experience mixed emotions tinged, perhaps, with apprehension — what is around the corner?

Sometimes participants in group clinical supervision leave the group because of a change of roles, e.g. promotion or a change in domestic circumstances. At such times acknowledgement must be given to the need of the individual and the group to say their goodbyes and prepare for change.

However, sometimes this is not possible. Turner et al (2005) recount how a group supervisor needed to leave suddenly because of illness:

After 14 months of supervision … Having thought we had reached a stage of independence from the supervisor, it was interesting and illuminating to realise this was not the case at all. In our first session ‘alone’, the old business like approach was again adopted, highlighting the tendency of the group, despite our best intentions, to go back to its old, safe comfortable way of operating …

It is possible that in times of change, a group, like individuals, might regress back to a stage where it found comfort. However, if the group can perceive this regression, it might strengthen its powers of self-analysis and inspire a determination to move forward once more.

A group can terminate before its intended ending because of a breakdown in relationships, either between the members themselves or between the members and their supervisor. Breakdowns in the supervisory relationship are, thankfully, rare in my experience. They can be due to unresolved personality clashes or power struggles in the group, breaks in confidentiality or feelings of insecurity.

The reason why supervisory relationship breakdowns are rare in groups is that the relationary process is often more transparent (being observed by several eyes) and therefore any possible trouble is identified before it leads to anything serious. Having a working agreement that is regularly reviewed, perhaps in the light of conflict, is an important consideration. If the group does break suddenly there is likely to be animosity and blame appointing but, even worse, the resulting damage may provoke a determination to never participate in group supervision again.

As discussed above, where possible it is important to mark the end of a group and, aside from group reviewing activities, I encourage groups to formally say goodbye. I have found it a nice idea to end with some sort of ceremony (in addition to handing in the standard evaluation forms). A technique I have used is to get participants to draw or sketch a parting gift for each person in the group (including the facilitator). These drawings are then formally presented to each participant to take forward into the future. We end by saying goodbye to each other.

This chapter, as the title suggested, has also been an adventure for me in sharing with you what I consider to be some key ideas for setting up your own group clinical supervision in practice while at the same time promoting collaborative working.