Body Fluids

Fluid in the cavities that surround organs may serve as a lubricant or shock absorber, enable the circulation of nutrients, or function for the collection of waste. Evaluation of body fluids may include total volume, gross appearance, total cell count, differential cell count, identification of crystals, biochemical analysis, microbiological examination, immunological studies, and cytological examination. The most common body fluid specimens received in the laboratory are cerebrospinal fluid (CSF); pleural, peritoneal, and pericardial fluids (together known as serous fluids); and synovial fluids. Under normal circumstances, the only fluid that is present in an amount large enough to sample is CSF. Therefore, when other fluids are present in detectable amounts, disease is suspected.

This atlas addresses primarily the elements of fluids that are observable through a microscope. For a more detailed explanation of body fluids, consult a hematology or urinalysis textbook that includes a discussion of body fluids, such as Rodak’s Hematology: Clinical Principles and Applications* or Fundamentals of Urine and Body Fluid Analysis.†

Because the number of cells in fluids is often very small, a concentrated specimen is preferable for performing the morphological examination. Preparation of slides using a cytocentrifuge is the method commonly used. This centrifuge spins at a low speed to minimize distortion of cells, concentrating the cells into a “button” on a small area of the glass slide. Slide preparation requires cytofunnel, filter paper to absorb excess fluid, and a glass slide. These elements are joined together in a clip assembly, and the entire apparatus is then centrifuged slowly. Excess fluid is absorbed by the filter paper, leaving a monolayer of cells in a small button on the slide. When the cytospin slide is removed from the centrifuge, it should be dry. If the cell button is still wet, the centrifugation time may need to be extended.

When preparing cytocentrifuge slides, a consistent amount of fluid should be used to generate a consistent yield of cells. Usually two to six drops of fluid are used depending on the nucleated cell count. Five drops of fluid will generally yield enough cells to perform a 100-cell differential if the nucleated cell count is at least 3/mm3. For very high counts, a dilution with normal saline may be made. The area of the slide where the cell button will be deposited should be marked with a wax pencil in case the number of cells recovered is small and difficult to locate (Figure 24–1). Alternatively, specially marked slides can be used.

There may be some distortion of cells as a result of centrifugation or when cell counts are high. Dilutions with normal saline should be made before centrifugation to minimize distortion when nucleated cell counts are high. When the red blood cell (RBC) count is extremely high (more than 1 million/mm3), the slide should be made in the same manner as the peripheral blood smear slide (see Chapter 1). However, the examination of the smear should be performed at the end of the slide rather than the battlement pattern used for blood smears. This is because the larger, and usually more significant, cells are likely to be pushed to the end of the slide.

When examining the cytospin slide, the entire cell button should be scanned under the 10× objective to search for the presence of tumor cells. The 50× or 100× oil immersion lens should be used to differentiate the white blood cells. For the performance of the differential, any area of the cell button may be used. If the cell count is low, a systematic pattern, starting at one end of the side of the button and working toward the other, is recommended.

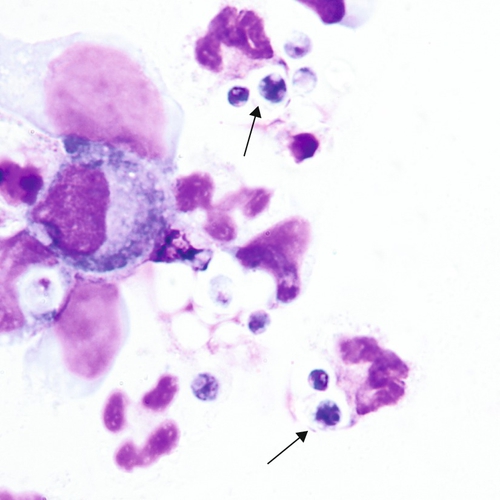

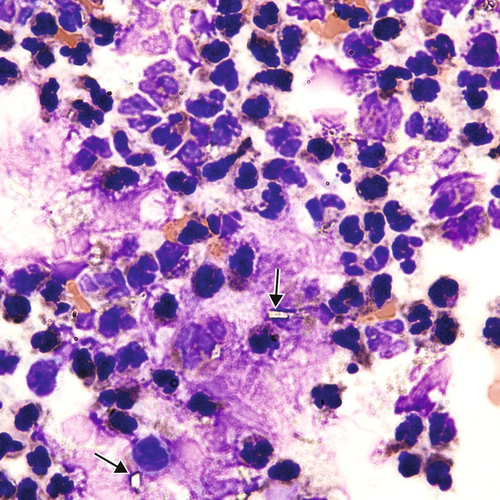

Any cell that is seen in the peripheral blood may be found in a body fluid in addition to cells specific to that fluid (e.g., mesothelial cells, macrophages, tumor cells). However, the cells look somewhat different than in peripheral blood, and some in vitro degeneration is normal. The presence of organisms, such as yeast and bacteria, should also be noted (see Figures 24–12 to 24–14).

Cells Commonly Seen In Cerebrospinal Fluid

Comments

Small numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes may be seen in normal CSF.

Increased numbers of neutrophils are associated with bacterial meningitis; early stages of viral, fungal, and tubercular meningitis; intracranial hemorrhage; intrathecal injections; central nervous system (CNS) infarct; malignancy; or abscess.

Increased numbers of lymphocytes and monocytes are associated with viral, fungal, tubercular, and bacterial meningitis and multiple sclerosis.

Cells Sometimes Found In Cerebrospinal Fluid

Reactive lymphocytes (Figure 24–5) are associated with viral meningitis and other antigenic stimulation. The cells will vary in size; nuclear shape may be irregular and cytoplasm may be scant to abundant with pale to intense staining characteristics. (See description of reactive lymphocytes, Figure 14–7.)

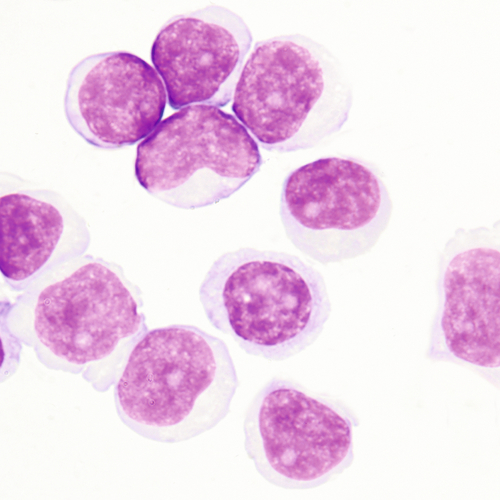

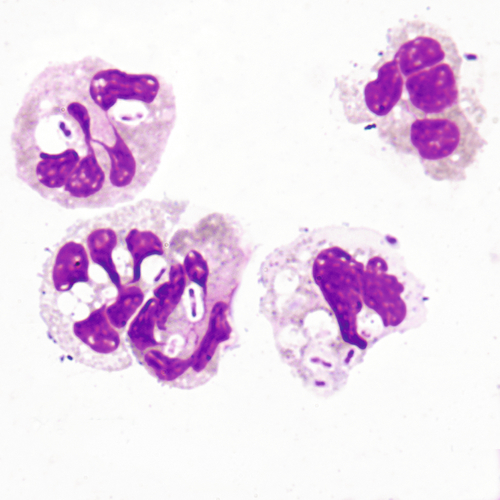

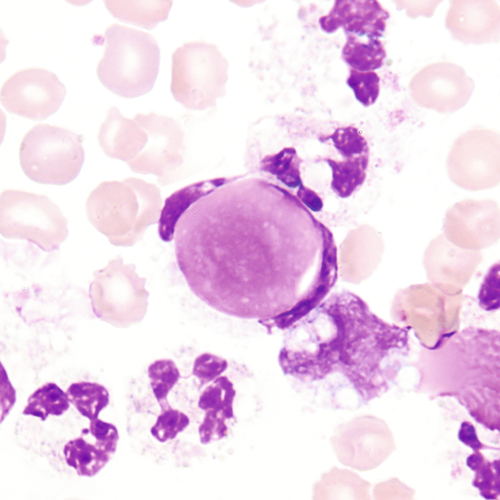

Blasts in the CSF may have some of the characteristics of the acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) blasts seen in the peripheral blood (Figure 24–6; see Chapter 16). It is not unusual for ALL to have CNS involvement, and blasts may be present in the CSF before being observed in the peripheral blood.

Associated with

Traumatic lumbar tap in premature infants, blood dyscrasias with circulating nucleated RBCs, and bone marrow contamination of CSF

Cells Sometimes Found In Cerebrospinal Fluid After Central Nervous System Hemorrhage

The following sequence of events is a typical reaction to intracranial hemorrhage or repeated lumbar punctures:

1. Neutrophils and macrophages: appear within 2 to 4 hours

2. Erythrophages: identifiable from 1 to 7 days

3. Hemosiderin and siderophages: observable from 2 days to 2 months

4. Hematoidin crystals: recognizable in 2 to 4 weeks.

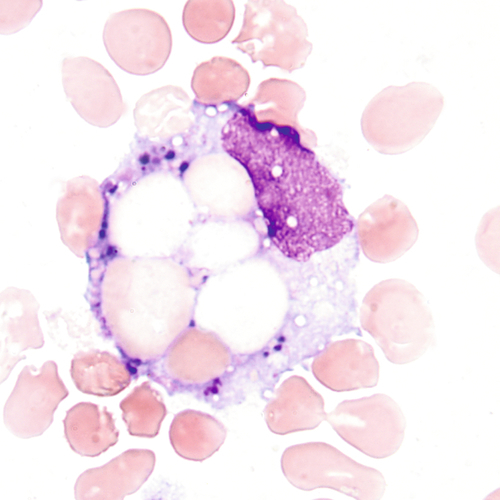

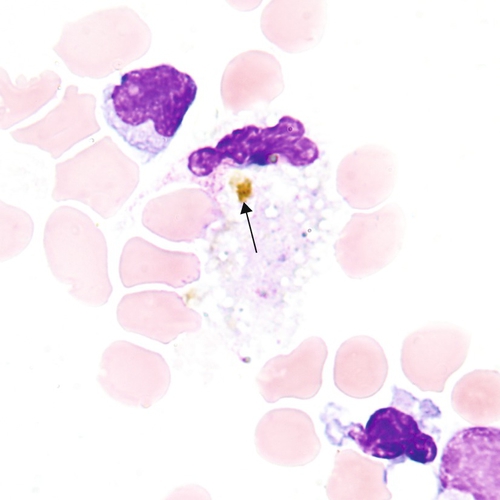

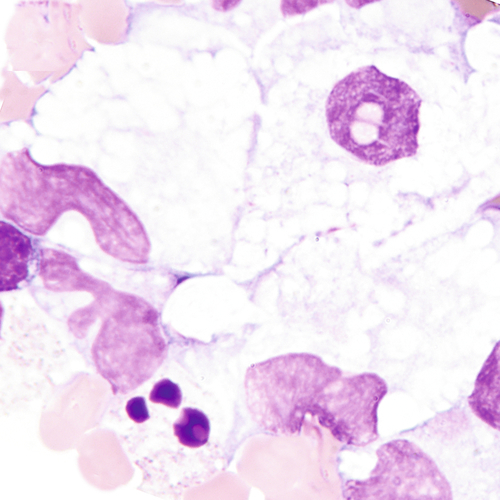

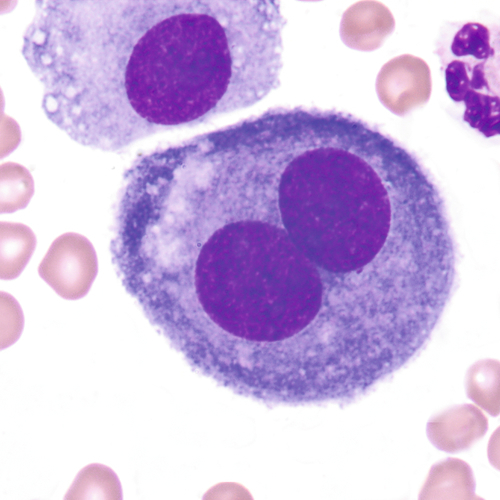

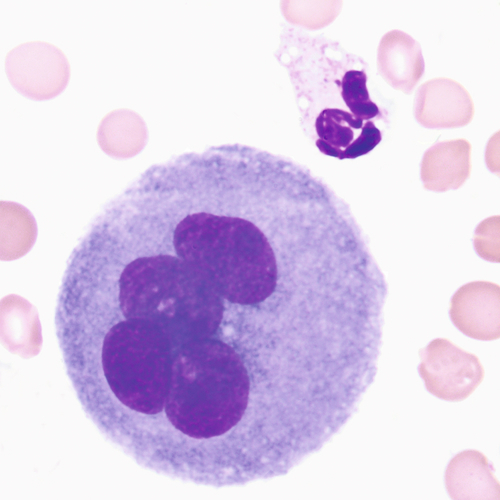

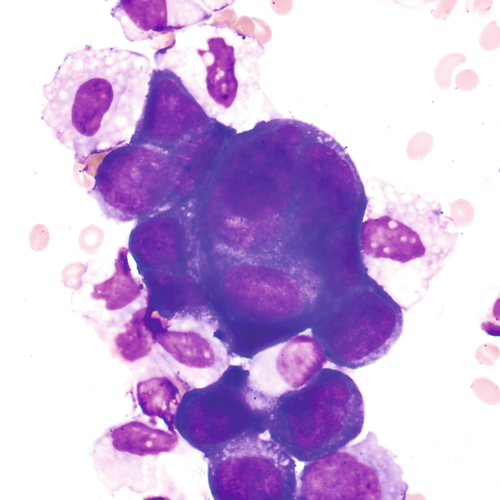

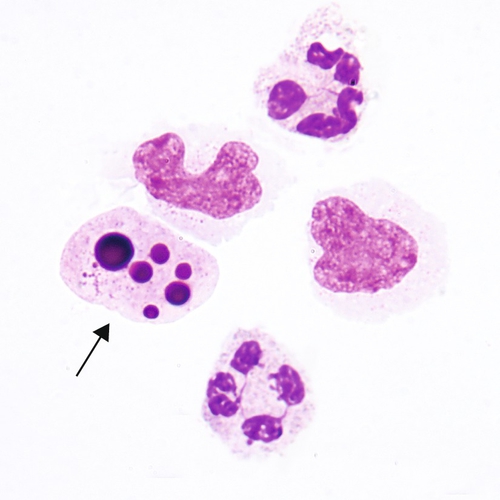

Macrophage with engulfed RBCs. RBCs are digested by enzymatic activity within the macrophage. The digestive process causes the RBCs to lose color and to appear as vacuoles within the cytoplasm of some macrophages.

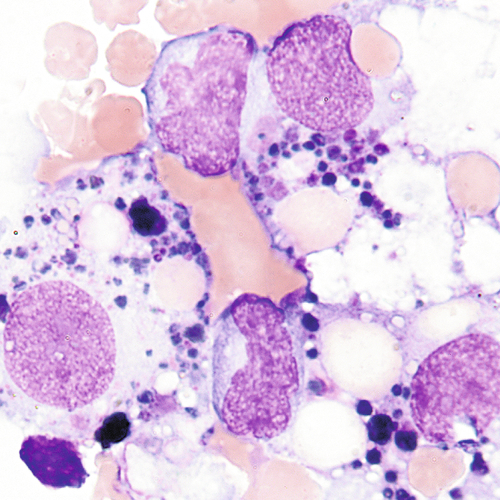

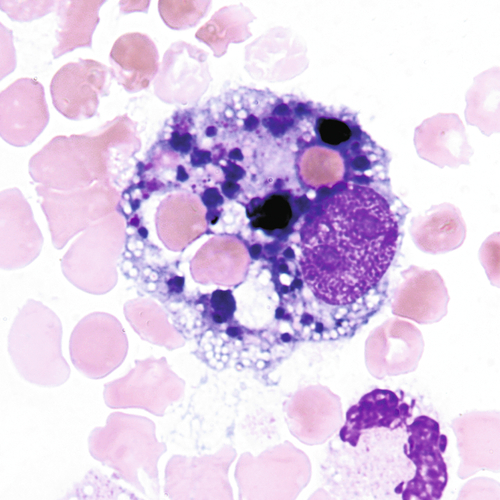

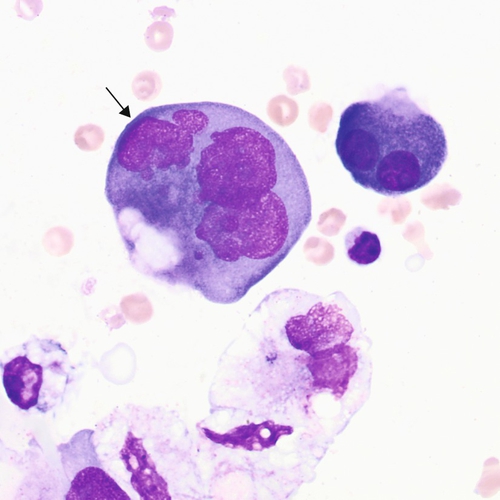

Blue to black granules that contain iron, resulting from the degradation of hemoglobin, may be present in CSF for up to 2 months after intracranial hemorrhage. The cellular inclusions can be positively identified with an iron stain.

Macrophage containing hemosiderin.

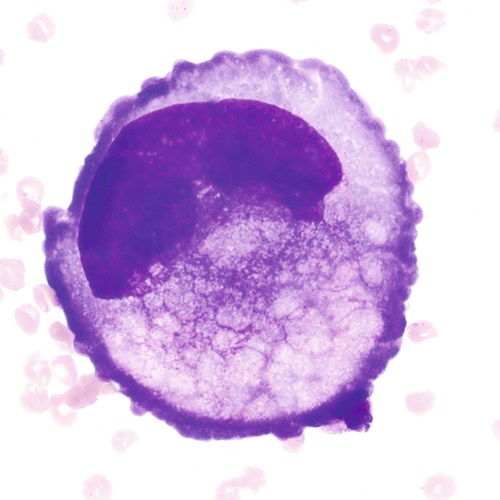

Gold intracellular crystals composed of bilirubin. Hematoidin is the result of the catabolism of hemoglobin and may be present for several weeks after CNS hemorrhage.

NOTE: Macrophages may display the presence of a variety of particles within one cell. For example, one macrophage may contain hemosiderin and hematoidin.

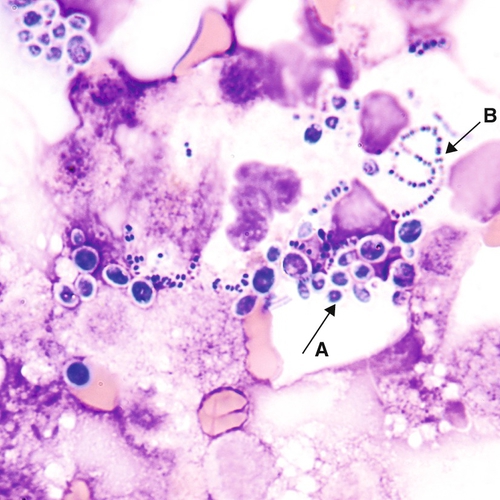

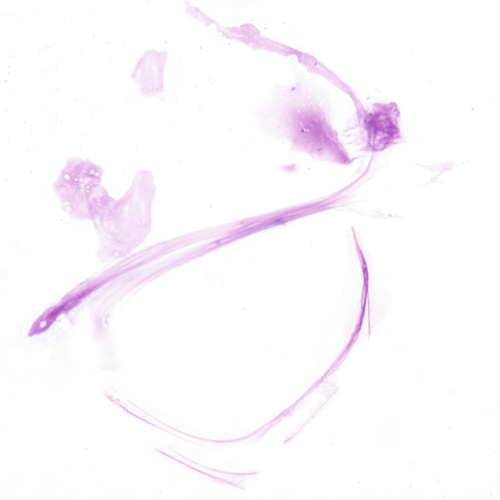

Organisms Sometimes Found In Cerebrospinal Fluid

CSF is a sterile body fluid. The following are examples of some organisms that have been seen in CSF, but it is far from an all-inclusive list of possibilities (Figures 24–12 to 24–14). Note that organisms may be intracellular, extracellular, or both.

Cells Sometimes Found In Serous Body Fluids (Pleural, Pericardial, And Peritoneal)

NOTE: Any of the cell types found in the peripheral blood may be found in serous fluids.

Description

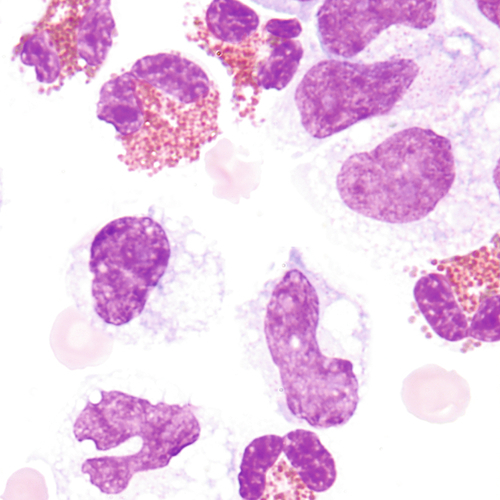

Large cells with eccentric nuclei and vacuolated cytoplasm may be present in all body fluids. They may be seen with or without inclusions, such as RBCs, siderotic granules, or lipids.

Description

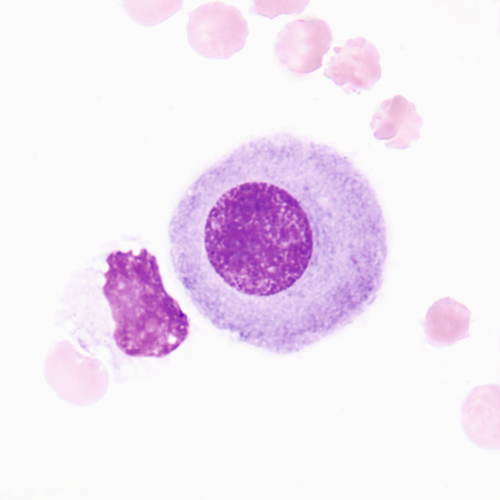

Round to oval cell with eccentric nuclei, dark blue cytoplasm, perinuclear hof 8 to 29 μm in diameter

Associated with

Rheumatoid arthritis, malignancy, tuberculosis, and other conditions that exhibit lymphocytosis

Associated with

Allergic reaction, air and/or foreign matter within the body cavity, parasites

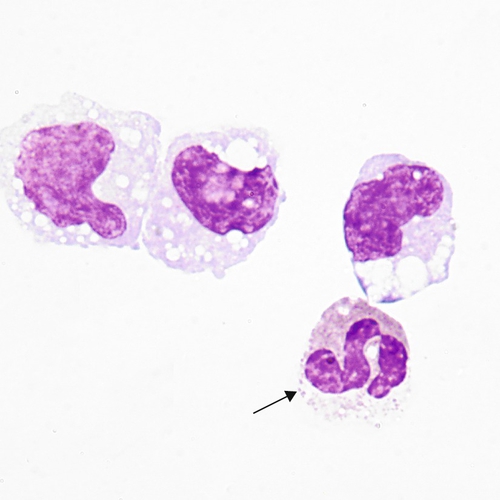

Intact neutrophil with engulfed homogeneous mass. The mass displaces the nucleus of the neutrophil and is composed of degenerated nuclear material. Lupus erythematosus (LE) cells are formed in vivo and in vitro in serous fluids. LE cells may also form in synovial fluids.

Associated with

Lupus erythematosus

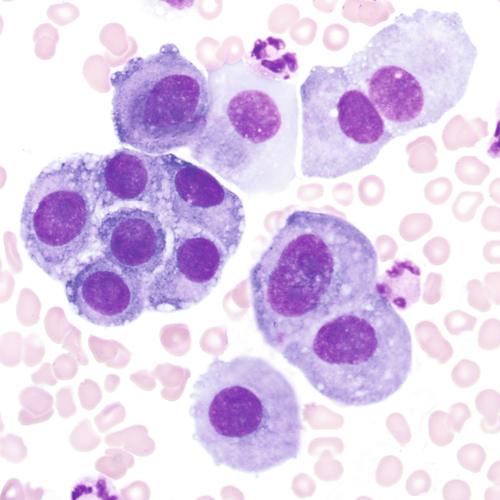

Mesothelial Cells

Mesothelial cells are shed from membranes that line body cavities and are often found in serous fluids.

MORPHOLOGY:

Shape

Pleomorphic

Size

12 to 30 μm

Nucleus

Round to oval with smooth nuclear borders; nucleus may be eccentric or multinucleated, making the distinction between the mesothelial and plasma cell difficult at times

Nucleoli:

1 to 3, uniform in size and shape

Chromatin:

Fine, evenly distributed

Cytoplasm

Abundant, light gray to deeply basophilic

Vacuoles:

Occasional

NOTE: Mesothelial cells may appear as single cells in clumps or sheets. The clumping of cells together and the variability of appearance require careful observation to accurately differentiate mesothelial cells from malignant cells. Three characteristics can aid in this determination:

1. Mesothelial cells on a smear tend to be similar to one another.

2. The nuclear membrane appears smooth by light microscopy.

3. Mesothelial cells maintain cytoplasmic borders. When appearing in clumps, there may be clear spaces between the cells. These spaces are often referred to as “windows.”

Multinucleated Mesothelial Cells

Table 24–1

Characteristics of Benign and Malignant Cells

| Benign | Malignant |

| Occasional large cells | Many cells may be very large |

| Light to dark staining | May be very basophilic |

| Rare mitotic figures | May have several mitotic figures |

| Round to oval nucleus; nuclei are uniform size with varying amounts of cytoplasm | May have irregular or jagged nuclear shape |

| Nuclear edge is smooth | Edges of nucleus may be indistinct and irregular |

| Nucleus intact | Nucleus may be disintegrated at edges |

| Nucleoli are small, if present | Nucleoli may be large and prominent |

| In multinuclear cells (mesothelial), all nuclei have similar appearance (size and shape) | Multinuclear cells have varying sizes and shapes of nuclei |

| Moderate to small N:C* ratio | May have high N:C ratio |

| Clumps of cells have similar appearance among cells, are on the same plane of focus, and may have “windows” between cells | Clumps of cells contain cells of varying sizes and shapes, are “three-dimensional” (have to focus up and down to see all cells), and have dark staining borders. No “windows” between cells |

From: Keohane EM, Smith LJ, Walenga JM (editors): Rodak’s Hematology: Clinical Principles and Applications, ed 5, St. Louis Elsevier/Saunders, 2016.

* N:C, nuclear:cytoplasmic.

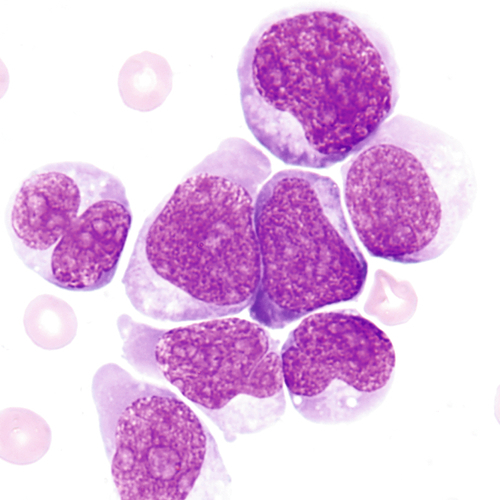

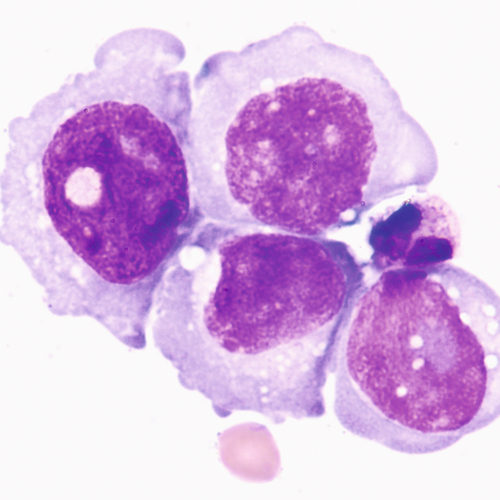

It is not always possible to distinguish malignant cells from mesothelial cells with the use of solely the light microscope. The following criteria for malignant cells may aid in this distinction.

Nucleus

High N:C ratio, membrane irregular

Nucleoli:

Multiple, large with irregular staining

Chromatin:

Hyperchromatic with uneven distribution

Cytoplasm

Irregular membrane

NOTE: Smears with cells displaying one or more of the above characteristics should be referred to a qualified cytopathologist for confirmation. See Table 24–1 for a comparison of benign and malignant features. Malignant cells tend to form clumps with cytoplasmic molding. The boundaries between cells may be indistinguishable.

Malignant Cells Sometimes Seen In Serous Fluids

Mitotic figures may be found in normal fluids and are not necessarily an indication of malignancy. The size of this mitotic figure, however, is quite large, and malignant cells were easily found.

Crystals Sometimes Found In Synovial Fluid

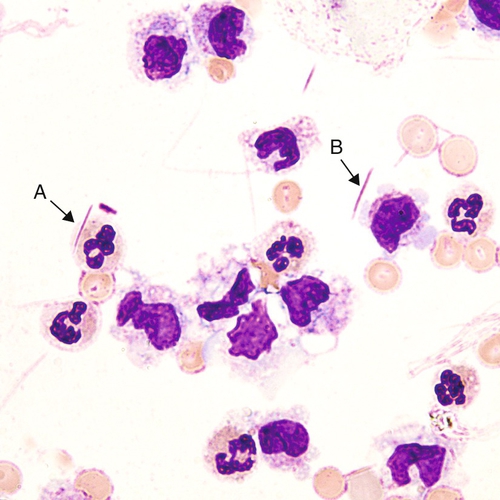

Cells that may be found in normal synovial fluids include lymphocytes, monocytes, and synovial cells. Synovial cells, which line the synovial cavity, resemble mesothelial cells (see Figure 24–19) but are smaller and less numerous. Increased numbers of polymorphonuclear neutrophils may be seen in bacterial infection and acute inflammation. When neutrophils are seen, a careful search for bacteria should be performed. Tumor cells are possible but quite rare. LE cells may also be seen (see Figure 24–18).

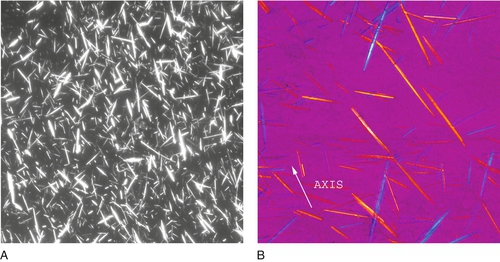

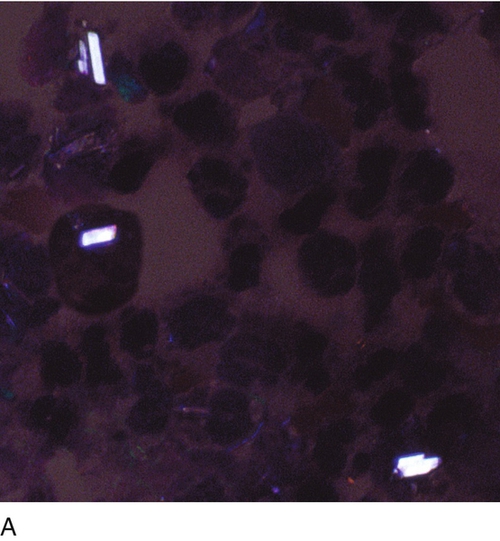

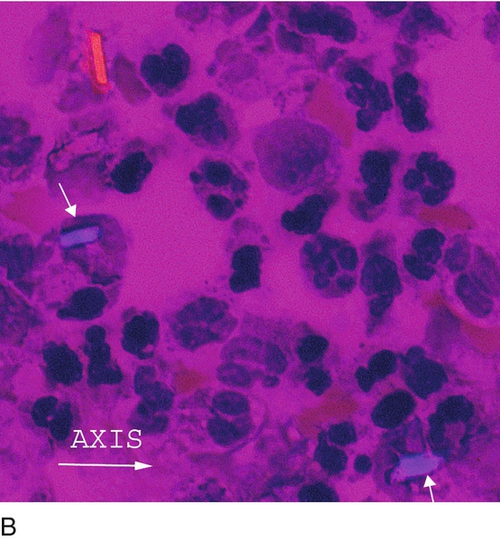

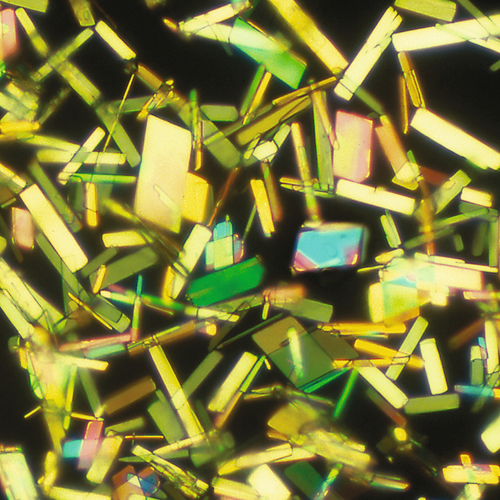

Each evaluation of synovial fluid should include a careful examination for crystals. Although it is not necessary to use a stain, Wright stain is sometimes used. A polarizing microscope with a red compensator should always be used for confirmation. The most common crystals are monosodium urate, calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate, and cholesterol.

Associated with

Gout

Notice the orientation of the crystals and corresponding colors. Crystals appear yellow when parallel to the axis of slow vibration and blue when perpendicular to the axis.

Rhomboid, rod-like chunky crystals may be intracellular, extracellular, or both.

Associated with

Pseudogout or pyrophosphate gout

Notice the orientation of the crystals and corresponding colors. Crystals appear blue when parallel to the axis of slow vibration and yellow when perpendicular to the axis. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate is only weakly birefringent, so that the colors are not as bright as monosodium urate crystals (see Figure 24–32).

Large, flat rectangular plates with notched corners.

Associated with

Chronic inflammatory conditions and considered a nonspecific finding

NOTE: It is necessary to use polarized light for confirmation of cholesterol crystals, but it is not necessary to use a red compensator.

Other Structures Sometimes Seen In Body Fluids

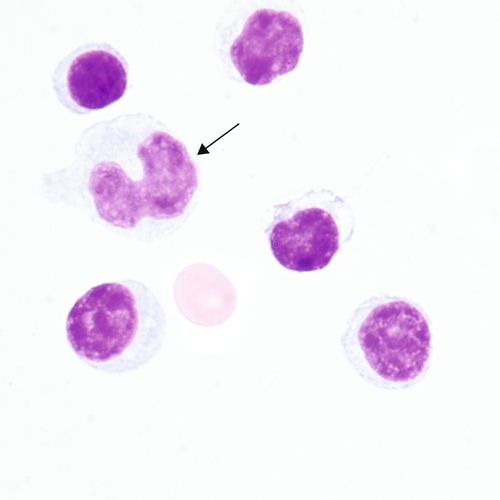

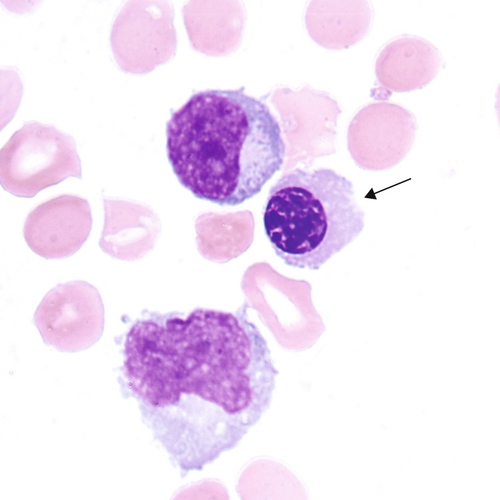

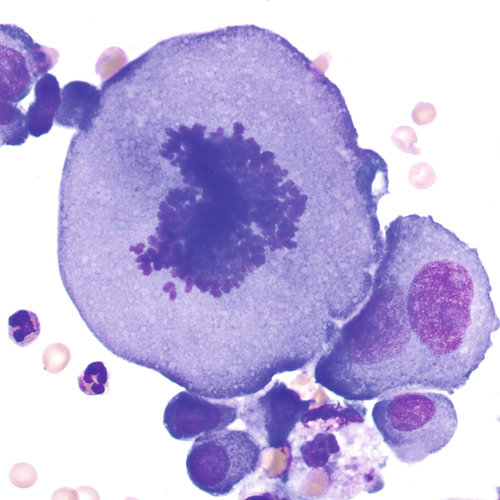

Intracellular nuclear degeneration appearing as darkly stained mass(es) (arrow), compared with two segmented neutrophils. Contrary to necrosis seen in peripheral blood, necrotic figures in body fluids can develop in vivo.

The specimen in Figure 24–39 is from a patient who experienced head trauma.

Fibers from the filter paper may appear near the edges of the slide. Fibers may be birefringent but lack the sharp pointed ends of monosodium urate crystals.