Chapter 66 Artemisia absinthium (Wormwood)

Artemisia absinthium (family: Asteraceae)

General Description

General Description

Artemisia absinthium generally occurs as an aromatic, semi-woody, perennial subshrub reaching up to 1 m tall, particularly in its native Mediterranean habitat. The leaves and flowers are used as medicine.

Chemical Composition

Chemical Composition

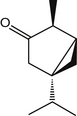

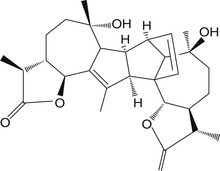

The aerial parts of wormwood contain two components considered most important to its medicinal activity: 0.15% to 0.4% volatile oil and 0.2% to 1.5% sesquiterpene lactones.1 The volatile oil is most notorious for its content of the terpenoids α- and β-thujone, given the potential neurotoxicity of these compounds. Alpha-thujone is believed to be much more toxic and is present as 0.53% to 1.22% of the volatile oil compared with 17.5% to 42.3% of β-thujone.2 Several chemotypes of wormwood depend on growing environment, and only certain ones contain thujone—others have trans-sabinyl acetate, cis-epoxyocimen, or chrysanthenyl acetate instead.1 Major sesquiterpene lactones present are absinthin, artabsin, matricin, and anabsinthin (Figures 66-1 to 66-3).

History and Folk Use

History and Folk Use

Wormwood was used historically as a digestive bitter in traditional herbal systems of various societies around its native Mediterranean habitat. The Ebers papyrus, an Egyptian medical treatise and one of the oldest extant pieces of writing (circa 1550 BC), mentions wormwood. Pliny the Elder discussed the use of wormwood to expel parasites, as reflected in the common name of the plant, in the first century AD.

The medicinal aspects of most of the history of wormwood are unfortunately overshadowed by development in the late eighteenth century of absinthe. The standard account of the rise of absinthe, a liqueur derived in part from wormwood, begins with French expatriate Pierre Ordinaire, who allegedly developed the first absinthe recipe in 1792 in Switzerland.3 Absinthe schnapps, absinthe-infused ale (known as “purl”), absinthe-infused wine, and other absinthe-containing beverages had been in use since Dioscorides’ time and probably before. Absinthe was apparently made by infusing wormwood, garden angelica root, anise fruit, and marjoram herb in ethanol; distilling them; and adding other flavorings, including volatile oils.3 The resulting product was bright green and intensely bitter, formed a white precipitate, and had a high alcohol content (50% to 80%).4

Henri Dubied and his son-in-law Henri Louis Pernod purchased Ordinaire’s formula and began producing large quantities of absinthe at the Pernod Fils distillery.4 One client for their product was the French military, which invaded Algeria from 1844 to 1847 and issued absinthe regularly to the troops to help prevent and treat dysentery. These troops apparently returned to France with a taste for absinthe and increased the popularity of the beverage.

Although originally absinthe was most popular with people in the lower classes, it caught on among the intelligentsia in the 1860s and 1870s, a time of cultural ferment, particularly in Paris. Parisians would gather in cafes to sip absinthe, often diluted by pouring cold water over a sugar cube held in a perforated spoon into a glass containing a shot of absinthe.5 Numerous famous artists of the time drank absinthe regularly, including Vincent van Gogh, whose insanity has been blamed (without proof) on his absinthe habit.

The growing popularity of absinthe, combined with a fire at the Pernod Fils distillery in 1901, led to a surge of absinthe-like products on the market. Unfortunately, these imitation products were often made as cheaply as possibly by simply mixing volatile oils with alcohol, adding various coloring agents to give the appropriate green hue (including copper sulfate), and antimony chloride to create the appearance of the white precipitate formed in true absinthe.3 At the same time, a new phenomenon termed absinthism was becoming widely known. This syndrome was a result of chronic absinthe overindulgence and included bursts of violent aggressiveness followed by prolonged depression, trembling, hallucinations, seizures, and death.5 However, the presence of adulterated, low-quality, high-ethanol absinthe products on the market and the inability to distinguish the effects of ethanol abuse from those of other compounds in the mixture made it difficult to be certain exactly what was causing absinthism. The levels of the purported neurotoxin thujone in true absinthe were 2 to 4 mg per drink, far below the 10 mg/kg levels needed to induce neurologic damage in numerous animal experiments.6 In the early twentieth century, absinthe was banned in most of Europe and the United States. Absinthe, usually with limits on thujone content, is now legal again in many places, including Europe and the United States.

The Eclectics regarded wormwood as a digestive tonic useful in atonic dyspepsia, as a potential treatment for roundworms, and for topical application to sprains and bruises.7 The dangers of absinthism were well known to these turn-of-the-century American natural physicians, but they did not seem clear on the various problematic elements in the history of absinthe discussed previously.

Pharmacology

Pharmacology

Wormwood’s actions have been studied in three major realms: digestive effects, antiparasitic effects, and effects on the central nervous system. Growing evidence suggests it is also a potent tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor. Various reported effects of isolated α- and β-thujone may also be relevant to wormwood’s effects.

Digestive Effects

In a controlled clinical trial, wormwood tincture and thujone-free wormwood tincture were both shown to significantly increase bile and pancreatic enzyme secretion in humans compared with water.8 The levels of secretion were assessed intraduodenally. These effects seem to be common to many bitter herbs that contain sesquiterpene lactones. Wormwood extract had a modest antidiarrheal effect in one rat model unrelated to infection.8a

Hepatic Effects

Pretreatment of mice with 500 mg/kg of wormwood extract decreased the 100% lethality of 1 g/kg acetaminophen to 20%.9 The toxicity of carbon tetrachloride was also reduced by pretreatment of rats with wormwood. Administering 500 mg/kg wormwood extract to rats 6 hours after toxic but sublethal doses of acetaminophen (but not carbon tetrachloride) significantly reduced hepatic damage. An aqueous extract of wormwood protected mice against carbon tetrachloride- and immune-mediated liver damage, partly by reducing oxidation and partly by inhibiting tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1.9a

Antiparasitic Effects

Wormwood does not appear to contain the same active constituents as sweet Annie, notably artemisinin, yet aqueous extracts of wormwood showed antimalarial effects in vitro.10 In mice, oral administration of extracts using 95% ethanol of wormwood was shown to have a potent schizonticidal effect against Plasmodium berghei, although not as potent as chloroquine.11,11a Activity of wormwood against multidrug resistant P. falciparum has been demonstrated in vitro.11a

Crude extracts of wormwood have been reported to inhibit other organisms in vitro or in animals, including Trypanosoma brucei, Trichinella spiralis, and nematodes.11b However, crude extract of wormwood was ineffective at treating infection with the nematode Haemonchus contortus.11c-11e

In vitro, aqueous, and ethanolic extracts of wormwood strongly inhibited the growth of the ameba Naegleria fowleri.12 The lowest concentration of a sesquiterpene lactone extract from wormwood that inhibited growth of the amebae to 50% or less than that of controls was 31.9 mg/mL compared with 0.025 mg/mL for amphotericin B. Apparently, research in India has shown an effect for wormwood against Entamoeba histolytica, but details of this publication could not be obtained.13

Neurologic Effects

Structural and biosynthetic similarities have long been noted among α- and β-thujone and tetrahydrocannabinol from Cannabis sativa (marijuana).14 Although thujone does weakly bind cannabinoid receptors in animals and human receptors in vitro, it does not appear to activate them.15 Wormwood oil also failed to have significant cannabinomimetic activity in this assay. Thujone’s purported hallucinogenic and epileptogenic effects have been disproven.15a An 80% ethanol extract of wormwood was a strong muscarinic and nicotinic cholinergic receptor agonist in vitro.16 Methanol extracts of wormwood at concentrations of 100 to 200 mg/kg significantly reduced memory loss and motor incoordination after middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats.16a

Clinical Applications

Clinical Applications

Wormwood was officially approved by the German Commission E for treatment of patients with dyspepsia, loss of appetite, and biliary dyskinesia.17 The article8 discussed in the “Pharmacology” section showing that wormwood could increase digestive secretions supports the use of wormwood for loss of appetite, although much more specific work is necessary for definitive proof of efficacy.

A randomized, double-blind clinical trial in Crohn’s disease found that wormwood extract, standardized to 0.2% to 0.38% absinthin and 0.25% to 0.52% total volatile oil (without thujone), in a base of rose petal, cardamom, and mastic gum or ginger (500 mg 3 times per day) was more effective than placebo at preventing relapse at 20 weeks.17a All patients were tapered off corticosteroids after 2 weeks on the medication. At a dose of 750 mg 3 times per day, this same extract has been shown to lower TNF-α levels in patients with Crohn’s disease over 6 weeks.17b

In an uncontrolled trial, the same extract mentioned earlier, at a dose of 600 mg 3 times per day in 10 patients with immunoglobulin-A nephropathy not responding to immunosuppressive medications, was effective at decreasing proteinuria and blood pressure over 6 months.17c Glomerular filtration rate remained stable, and there were no adverse effects.

Dosage

Dosage

Wormwood is primarily used in three forms—tea, tincture, and capsule. Volatile oil should not be used. A typical dose of tea is 1 g (1 to 2 tsp) dried leaf and flower per cup of water, steeped for 10 to 15 minutes.18 The tea should be covered during steeping to retain as many volatile constituents as possible. A cup of tea is sipped before meals three times daily. Thujone is not water soluble, so aqueous extracts of the plant are generally low in thujone. A typical dose of tincture is 0.5 to 1 mL 3 times daily mixed with 2 to 4 oz water, sipped before meals. A typical capsule dose is 2 to 3 g/day in divided doses.19

Toxicity

Toxicity

Although much toxicity is ascribed to wormwood, it now appears that this is largely the result of poor research methodology in the early twentieth century and improperly conflating wormwood volatile oil and absinthe.15a Any toxicity attributed to the use of various forms of the beverage absinthe must not be confused with use of teas or tinctures in medicinal doses. Alpha-thujone is considered a neurotoxin and convulsant compound.20 Beta-thujone, present in much higher levels in wormwood, is generally considered much less toxic.21 In mice, α- and β-thujone both antagonized γ-aminobutyric acid-A receptors and induced seizures.22 Alpha-thujone was a much stronger convulsant than β-thujone in this study. This study confirmed previous findings that thujone is rapidly metabolized by the liver and removed from the body in animals.23

A 31-year-old man who drank 10 mL of wormwood volatile oil, mistakenly believing it was identical to absinthe, became agitated, belligerent, and incoherent, and developed tonic-clonic seizures.24 Haloperidol improved his mental function, but acute renal failure and rhabdomyolysis were discovered, becoming worse a day later. Congestive heart failure developed, in part due to aggressive alkalinization. Seventeen days after discharge from the hospital he had recovered completely.

These effects have never been documented to occur in patients being treated with reasonable doses of medicinal extracts of or crude wormwood. In one naturopathic medical practice, nine patients over a 3-year period were identified who had been treated with a bitters formula including 11% tincture of wormwood, generally as a treatment for dyspepsia or malabsorption.25 Administered at a dose of 1 teaspoon (5 mL) 3 times daily, patients would have been exposed to approximately 500 mL wormwood tincture 3 times daily for weeks to months. For the eight patients with available laboratory data, there was no evidence of renal, hepatic, or other damage. One patient showed improvement in serum liver enzyme levels while taking the bitters formula. None of the patients developed seizures or other signs or symptoms of neurotoxicity. Although retrospective, this study did support the notion that wormwood in this form and at this dose is safe for use in adults as a digestive aid.

Thujone stimulates 5-aminolevulinate synthase in vitro, leading to large increases in porphyrin levels.26 Although it seems likely that porphyrogenic levels of thujone could be achieved by drinking large volumes of absinthe, levels of intake of tincture of wormwood are far lower and unlikely to lead to such high levels. Porphyrogenic effects have not been clearly documented to be induced by wormwood in humans, although thujone and thujone-containing herbs such as wormwood should be avoided by people with porphyria until more information is available.

Drug Interactions

Drug Interactions

No confirmed drug interactions exist for wormwood. It should be avoided in combination with chronic ethanol abuse due to historic reports pertaining to absinthe. Given the low doses of tinctures used, this should not represent any health threat related to ethanol ingestion. Wormwood may have synergistic porphyrogenic effects with other drugs that can induce porphyric attacks, including barbiturates, hydantoins, and carbamazepine.

1. Bisset N.G., Wichtl M. Herbal drugs and phytopharmaceuticals. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 1994:45–48.

2. Lawrence B.M., ed. Perfumer and flavorist. Essential oils 1992-1994. Natural flavor and fragrance materials. Carol Stream, IL: Allured Publishing Corporation. 1995:11–14.

3. Vogt D.D. Absinthium: a nineteenth-century drug of abuse. J Ethnopharmacol. 1981;4:337–342.

4. Vogt D.D., Montagne M. Absinthe: behind the emerald mask. Int J Addict. 1982;17:1015–1029.

5. Haines J.D. Absinthe—return of the green fairy. J Okla State Med Assoc. 1998;91:406–407.

6. Tisserand R., Balacs T. Essential oil safety: a guide for health care professionals. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995.

7. Felter H.W. Eclectic materia medica, pharmacology and therapeutics. Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications; 1922. reprinted 1998

8. Baumann I.C., Glatzel H., Muth H.W. Studies on the effects of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium L.) on bile and pancreatic juice secretion in man. Z Allgemeinmed. 1975;51:784–791.

8a. Calzada F., Arista R., Pérez H. Effect of plants used in Mexico to treat gastrointestinal disorders on charcoal-gum acacia-induced hyperperistalsis in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:49–51.

9. Gilani A.H., Janbaz K.H. Preventive and curative effects of Artemisia absinthium on acetaminophen and CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity. Gen Pharmacol. 1995;26:309–315.

9a. Amat N., Upur H., Blazekovic B. In vivo hepatoprotective activity of the aqueous extract of Artemisia absinthium L. against chemically and immunologically induced liver injuries in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;131:478–484.

10. Hernandez H., Mendiola J., Torres D., et al. Effect of aqueous extracts of Artemisia on the in vitro culture of Plasmodium falciparum. Fitoterapia. 1990;61:540–541.

11. Zafar M.M., Hamdard M.E., Hameed A. Screening of Artemisia absinthium for antimalarial effects on Plasmodium berghei in mice: a preliminary report. J Ethnopharmacol. 1990;30:223–226.

11a. Ramazani A., Sardari S., Zakeri S., et al. In vitro antiplasmodial and phytochemical study of five Artemisia species from Iran and in vivo activity of two species. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:593–599.

11b. Nibret E., Wink M. Volatile components of four Ethiopian Artemisia species extracts and their in vitro antitrypanosomal and cytotoxic activities. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:369–374.

11c. Squires J.M., Ferreira J.F., Lindsay D.S., et al. Effects of artemisinin and Artemisia extracts on Haemonchus contortus in gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus). Vet Parasitol. 2011;175:103–108.

11d. Caner A., Döskaya M., Degirmenci A., et al. Comparison of the effects of Artemisia vulgaris and Artemisia absinthium growing in western Anatolia against trichinellosis (Trichinella spiralis) in rats. Exp Parasitol. 2008;119:173–179.

11e. Tariq K.A., Chishti M.Z., Ahmad F., et al. Anthelmintic activity of extracts of Artemisia absinthium against ovine nematodes. Vet Parasitol. 2009;160:83–88.

12. Mendiola J., Bosa M., Perez N., et al. Extracts of Artemisia abrotanum and Artemisia absinthium inhibit growth of Naegleria fowleri in vitro. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85:78–79.

13. Tahir M, Khan AB, Siddiqui MMH. Effect of Artemisia absinthium Linn in acute intestinal amebiasis. Presented at Conference of Pharmacology and Symposium on Herbal Drugs. New Delhi, India. March 15, 1991.

14. del Castillo J., Anderson M., Rubottom G.M. Marijuana, absinthe and the central nervous system. Nature. 1975;253:365–366.

15. Meschler J.P., Howlett A.C. Thujone exhibits low affinity for cannabinoid receptors but fails to evoke cannabimimetic responses. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;62:473–480.

15a. Padosch S.A., Lachenmeier D.W., Kröner L.U. Absinthism: a fictitious 19th century syndrome with present impact. Substan Abuse Treat Prevent Policy. 2006;1:14.

16. Wake G., Court J., Pickering A., et al. CNS acetylcholine receptor activity in European medicinal plants traditionally used to improve failing memory. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;69:105–114.

16a. Bora K.S., Sharma A. Neuroprotective effect of Artemisia absinthium L. on focal ischemia and reperfusion-induced cerebral injury. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;129:403–409.

17. Blumenthal M., Busse W.R., Goldberg A., et al. The complete German Commission E monographs: therapeutic guide to herbal medicines. Austin, TX: American Botanical Council. 1998:232–233.

17a. Omer B., Krebs S., Omer H., et al. Steroid-sparing effect of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) in Crohn’s disease: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Phytomedicine. 2007;14:87–95.

17b. Krebs S., Omer T.N., Omer B. Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) suppresses tumour necrosis factor alpha and accelerates healing in patients with Crohn’s disease—a controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:305–309.

17c. Krebs S., Omer B., Omer T.N., et al. Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) for poorly responsive early-stage IgA nephropathy: a pilot uncontrolled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:1095–1099.

18. Windholz M., Budavari S., Blumetti R.F., et al. The Merck index. Rahway, NJ: Merck & Co, 1983.

19. Duke J.A. Handbook of medicinal herbs, 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002. 798-799

20. Summary of data for chemical selection alpha-thujone 546-80-5. National Toxicology Program. Available online at http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/?objectid=03DB8C36-E7A1-9889-3BDF8436F2A8C51F Accessed 10/13/2011

21. Arnold W.N. Vincent van Gogh and the thujone connection. JAMA. 1988;260:3042–3044.

22. Höld K.M., Sirisoma N.S., Ikeda T., et al. Alpha-thujone (the active component of absinthe): gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor modulation and metabolic detoxification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3826–3831.

23. Höld K.M., Sirisoma N.S., Casida J.E. Detoxification of alpha- and beta-thujones (the active ingredients of absinthe): site specificity and species differences in cytochrome p450 oxidation in vitro and in vivo. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:589–595.

24. Weisbord S.D., Soule J.B., Kimmel P.L. Poison on line—acute renal failure caused by oil of wormwood purchased through the Internet. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:825–827.

25. Heron S., Yarnell E. Retrospective analysis of the safety of bitter herbs with an emphasis on Artemisia absinthium L (wormwood). J Naturopathic Med. 2000;9:32–39.

26. Bonkovsky H.L., Cable E.E., Cable J.W., et al. Porphyrogenic properties of the terpenes camphor, pinene, and thujone. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:2359–2368.