Symphonological bioethical theory

Carrie Scotto

Gladys L. Husted (1941–Present)

James H. Husted(1931–Present)

“Symphonology (from ‘symphonia,’ a Greek word meaning agreement) is a system of ethics based on the terms and preconditions of an agreement.”

Husted & Husted, 2001, p. 34

Credentials and background of the theorists

Gladys Husted was born in Pittsburgh, where her life, practice, education, and teaching continue to influence the nursing profession. Husted received a Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree from the University of Pittsburgh in 1962 and began practice in public health and acute inpatient medical-surgical care. Observations of interactions between nurses and patients initiated her interest in ethical issues. In 1968 she earned a master’s degree in nursing education while teaching at the Louise Suyden School of Nursing at St. Margaret’s Memorial Hospital in Pittsburgh. Her love of teaching prompted doctoral study that resulted in a terminal degree from the University of Pittsburgh Department of Curriculum and Supervision.

G. Husted is professor emeritus at Duquesne University School of Nursing, where in 1998 she was awarded the title of School of Nursing Distinguished Professor. She was also recognized for teaching excellence at all levels of the curriculum with the Duquesne University School of Nursing Recognition Award for Excellence, 1990/1991, and the Faculty Award for Excellence in Teaching, 1994/1995. The Medical College of Ohio chose Husted as Distinguished Lecturer in 2000. She is a member of Sigma Theta Tau International, Phi Kappa Phi, and the National League for Nursing.

G. Husted consulted with the Western Pennsylvania Hospital Nursing Division developing an ethics committee, educating staff and management, and providing guidance for the newly formed committee. She also consulted with Allegheny General Medical Center for staff development and the National Nursing Ethics Advisory Group for the Department of Veterans Affairs. G. Husted served as curriculum consultant for several schools of nursing and has presented at many national-level conferences.

James Husted was born in Kingston, Pennsylvania, and has had a lifelong interest in philosophy. While in the army in Germany, he became interested in ethics through conversations with a former ethics professor, particularly the work of Benedict Spinoza. His post-army career focused on sales and on hiring and training agents for health insurance companies. However, he continued to read and develop his philosophical and ethical ideas. During the 1980s he joined the high-IQ societies Mensa and Intertel, serving as a philosophy expert for Mensa and a regional director for Intertel.

The theorists met and were married in 1974, establishing and cultivating a dialogue that brought about the theory of symphonology. They are coauthors of several editions of Ethical Decision Making in Nursing. Their book was selected as one of Nursing and Health Care’s Notable Books of 1991, 1995, and 2001. It also won the Nursing Society Award in 2001. Their regular column, “A Practice Based Bioethic,” appeared in Advanced Practice Nursing Quarterly from 1997 to 1998. In addition to publishing books, book chapters, and journal articles, they have presented their ethical theory at conferences and workshops.

The Husteds reside in Pittsburgh and for many years continued to develop and disseminate their work through teaching, writing, presenting at conferences and workshops, and serving as consultants for ethics committees. Both are now retired.

Theoretical sources

The authors define symphonology as “the study of agreements and the elements necessary to forming agreements,” (Husted et al, 2015, p. x). In health care, it is the study of agreements between health care professionals and patients. An agreement is based on the nature of the relationship between the parties involved. In its ethical dimensions, it outlines the commitments and obligations of each. Although the theory developed from the observation of nurses and nursing practice, it later expanded to include all health care professionals. The development of this theory has led to the construction of a practice-based decision-making model that assists in determining when and what actions are appropriate for health care professionals and patients. The name of the theory is derived from the Greek word symphonia, which means “agreement.”

Ethics is “a system of standards to motivate, determine, and justify actions directed to the pursuit of vital and fundamental goals” (Husted et al, 2015, p. 1). Ethics examines what ought to be done, within the realm of what can be done, to preserve and enhance human life. The Husteds, therefore, describe ethics as the science of living well.

Bioethics is concerned with the ethics of interactions between a patient and a health care professional, what ought to be done to preserve and enhance human life within the health care arena. Within the past century, the expanding knowledge base and growth of technology altered existing health care practice and created threatening and confusing circumstances not previously encountered. Increasing numbers and types of treatment options allowed patients to survive conditions they would not have in the past. However, the morbidity of the survivors brought new questions: Who should receive treatment? What is the appropriateness of treatments under particular circumstances? Who should decide what treatments are appropriate? In this way, bioethics became a central issue in what previously had been a prescriptive environment. It became essential to consider ethical concerns, as well as scientific solutions, to questions of health (Jecker, Jonsen, & Pearlman, 1997). Through personal experience and observation of nurses, the Husteds recognized the increasingly complex nature of bioethical dilemmas and the failure of the health care system to adequately address them.

To clarify the reasons for the deficiency of the health care system in addressing the issue of delivering ethical care, the Husteds examined traditional ideas and concepts used to guide ethical behavior. These ideas include deontology, utilitarianism, emotivism, and social relativism. Deontology is a duty-based ethic in which the consequences of one’s actions are irrelevant. One acts in accordance with preset standards regardless of the outcome. The inappropriateness of this type of guideline is obvious in relation to health care professionals, because they are responsible for foreseeing the effects of their actions and acting only in ways that benefit a patient. Utilitarian thought would have health care professionals acting to bring about the greatest good for the greatest number of people. This is inconsistent with the practice of health care professionals who act as agents for individual patients. Emotivism promotes ethical actions in accordance with the emotions of those involved. Rational thought has no place in emotive choices, making this type of decision-making process inappropriate in the health care arena. Social relativism imposes the beliefs of a society onto the individual. This approach is incongruous with the increasing diversity of our emerging global society. The Husteds recognized that the inappropriateness of traditional methods of ethical reasoning brought about the failure of the health care system to successfully address bioethical issues.

Because traditional models proved inadequate to guide ethical behavior for health care professionals, the Husteds began to conceive and develop a method by which health care professionals might determine appropriate ethical actions. The theory was based on logical thinking, emphasizing the provision of holistic, individualized care. They drew from the work of Aristotle, Benedict Spinoza, and Michael Polanyi. These philosophers adhere to rational thought and value persons as individuals. Aristotle, a student of Plato, advanced his teacher’s work by recognizing that there is more to understanding phenomena than simple rationality. He believed that one must develop insight and perception to recognize how principles can be applied to each situation (McKeon, 1941).

The Dutch philosopher Spinoza examined the nature of humans and human knowledge. He recognized that although the process and outcomes of reasoning may be comparable for each person, intuitive and discerning thought is unique to each. Spinoza believed that reason must be coupled with intuitive thought for true understanding (Lloyd, 1996). Spinoza was noted for taking well-worn philosophical concepts and transforming them into new and engaging ideas. This is true of the Husteds’ development of symphonology, particularly in the evolution of the meaning of bioethical standards.

Polanyi (1964) proposed that understanding is derived from awareness of the entirety of a phenomenon, that the lived experience is greater than separate, observable parts. Tacit knowledge, that which is implied, is necessary to understand and interpret that which is explicit (Polanyi, 1964). These concepts, the uniqueness of the individual and the extension of reason and rationality with insight and discernment to create true understanding, are the foundations of the symphonological method.

Use of empirical evidence

Study and dialogue between the two theorists, coupled with experience of the overall evolution of health care and observation of individual nurse–patient relationships, provided the impetus to develop symphonology theory. G. Husted’s dissertation focused on the effect of teaching ethical principles on a student’s ability to use these in practical ways through case studies. J. Husted was very instrumental in the selection of the dissertation topic and was used as a consultant during the process. Development of G. Husted’s doctoral work led to numerous publications and presentations before the first edition of the book Ethical Decision Making in Nursing was published in 1991. This first edition presented their work as a conceptual model only. As they continued to develop their ideas, incorporating feedback from graduate students, the symphonological theory emerged. Before publication of the second edition, the Husteds (1995a) continued to clarify the theoretical concepts and developed the model for practice.

Beginning in 1990, Duquesne University offered a course devoted to this bioethical theory. The authors continued to seek critique and examples about their work from students, practitioners, and other experts. The third edition of the book, Ethical Decision Making in Nursing and Healthcare: The Symphonological Approach (Husted & Husted, 2001), offered a clarified description of the theory, with advanced concepts separated from the basic concepts. In addition, the model was redrawn to better represent the nonlinear nature of the theory in practice. The fourth edition offers further clarification of concepts and the integration of concepts in the theory as a whole. In addition, the text is rearranged to present the concepts from simple to more complex. The fifth edition, published in 2015, includes two former doctoral students as coauthors who use the model in practice and have added to the continued development and clarification of the model. In the fifth edition the concepts of freedom and self-assertion were merged. The authors agreed that these concepts were the same and distinguished from each other only by time. They chose to keep the term freedom because most people can relate to that term.

As the theory emerged, the need for an emphasis on the individual became apparent and essential. In recent years, it has become accepted practice in the literature to designate patients and nurses as “he/she,” or simply use the plural form, referring to nurses and their patients. The authors recognized that these awkward and anonymous terms distract readers from thinking in terms of real people within the context of a particular situation. Therefore they chose to refer to individuals as he, in the case of patients, and she, in the case of health care professionals in particular situations and examples. This chapter continues with that practice.

Major assumptions

The assumptions from this theory arise from the practical reasoning. The model is meant to provide nurses and other health care professionals with a logical method of determining appropriate ethical actions. Although many of the terms are familiar to nurses and health care professionals, some have been redefined to support the reality of human interaction and ethical delivery of health care.

Nursing

Symphonology holds that a nurse or any other health care professional acts as the agent of the patient. Using her education and experience, a nurse does for her patient what he would do for himself if he were able. Nursing cannot occur without both nurse and patient. “A nurse takes no actions that are not interactions” (Husted & Husted, 2001, p. 37). The nurse’s ethical responsibility is to encourage and strengthen those qualities in the patient that serve life, health, and well-being through their interaction (Fedorka & Husted, 2004).

Agency is the capacity of an agent to take action toward a chosen goal. A nurse as agent takes action for a patient, one who cannot act on his own behalf. The shared goal of a nurse and a patient is to restore the patient’s agency. The nurse acts with and for the patient toward this end.

Person or patient

The Husteds define a person as an individual with a unique character structure possessing the right to pursue vital goals as he chooses (Husted et al, 2015). Vital goals are concerned with survival and the enhancement of life. A person takes on the role of patient when he has lost or experienced a decrease in agency, resulting in his inability to take the actions required for survival or happiness. The inability to take action may result from physical or mental problems or from a lack of knowledge or experience (Husted & Husted, 1998).

Health

Health is not defined directly by the Husteds. The entire theory is driven by the concept of health in the broadest, most holistic sense. Health is a concept applicable to every potential of a person’s life. Health involves not only thriving of the physical body, but also happiness. Happiness is realized as individuals pursue and progress toward the goals of their chosen life plan (Husted et al, 2015). Health is evident when individuals experience, express, and engage in the fundamental bioethical standards.

Environment or agreement

The environment established by symphonology is formed by agreement. “Agreement is a shared state of awareness on the basis of which interaction occurs” (Husted et al, 2015, p. 32). Agreement creates the realm in which nursing and all other human interactions occur. Every agreement is aimed toward a final value to be attained through interactions made possible by understanding.

The health care professional–patient agreement is formed by a meeting of the professional’s and the patient’s needs. Their agreement is one in which the needs and desires of the patient are central. The professional’s commitment is defined in terms of the patient’s needs. Without this agreement, there would be no context for interaction between the two. The relationship would be unintelligible to both (Husted & Husted, 1999).

Symphonology theory is not a compilation of traditional cultural platitudes. It is a method of determining what is practical and justifiable in the ethical dimensions of professional practice. Symphonology recognizes that what is possible and desirable in the agreement is dependent on the context.

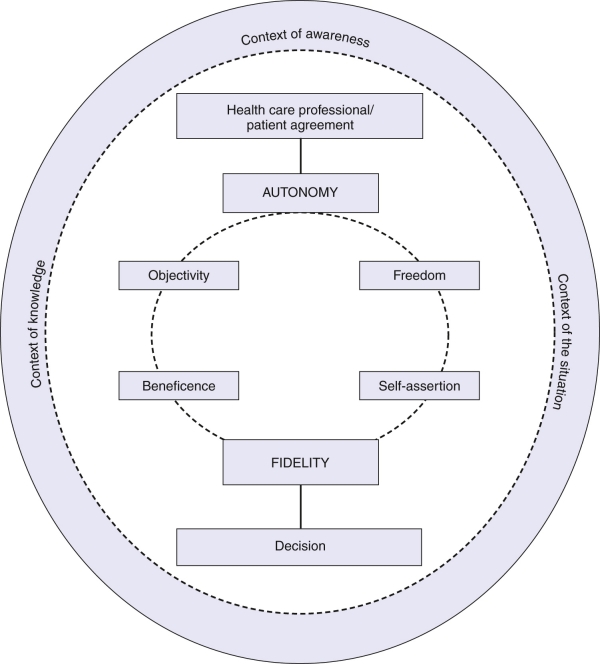

The context is the interweaving of the relevant facts of a situation—the facts that are necessary to act upon to bring about a desired result (Husted & Husted, 2001). There are three interrelated elements of context: the context of the situation, the context of knowledge, and the context of awareness. The context of the situation includes all facts relevant to the situation that provide understanding of the situation and promote the ability to act effectively within it. The context of knowledge is an agent’s preexisting knowledge of the relevant facts of the situation. The context of awareness represents an integration of the agent’s awareness of the facts of the situation and her preexisting knowledge about how to most effectively deal with these facts (Husted & Husted, 2008).

Theoretical assertions

Symphonology is classified as a grand theory because of its broad scope. Grand theories structure goals related to a specific view of the discipline (Walker & Avant, 2011). Grand theories are broader than conceptual models and may be used as a model to guide practice and research (Fawcett & Garity, 2009). The authors developed symphonology theory from the recognition of a need for theoretical guidelines related to the ethical delivery of health care. The understanding and use of this theory are based on a fundamental ethical element that describes the rational relationship between human beings: human rights.

Rights

The Husteds describe rights as the fundamental ethical element. Traditionally, rights are viewed as a list of options to which one is entitled, a list of items or actions to which one has a just claim. Symphonology holds rights as a singular concept. It is the implicit, species-wide agreement that one will not force another to act, or take by force the products of another’s actions. Rights are viewed as the critical agreement among rational people, the agreement of nonaggression (Husted & Husted, 1997a). This agreement emerged as humans became rational and developed a civilized social structure. A nonaggression agreement is preconditional to all civilized human interaction. It serves as a foundation on which all other agreements rest. The formal definition is as follows: “the product of an implicit agreement among rational beings, held by virtue of their rationality, not to obtain actions or the products of actions from others except through voluntary consent, objectively gained” (Husted et al, 2015, p. 20). The operation of this is evident in human interaction.

Symphonology theory can ensure ethical action in the provision of health care. Agreement is the foundation of symphonology. Agreements occur based on the implicit understanding of human rights. The understanding of nonaggression that exists among rational persons constitutes human rights. This understanding makes negotiation and cooperation among individuals possible.

Ethical standards

Ethical standards have been the benchmarks of ethical behavior. The standards include terms familiar to health care professionals such as beneficence, veracity, and confidentiality. However, the Husted et al, (2015) have conceived new meanings for ethical standards that correspond to the foundational concepts of symphonology: the person as a unique individual and the use of insight and discernment in addition to reason and rationality to achieve a deeper understanding.

Traditionally, bioethical concepts have been used to guide ethical action by mandating concrete directives for action. For instance, the concept of beneficence conventionally maintains that one must see that no harm comes to a patient. However, it is not always possible to predict how and when harm will occur, making adherence to this directive an unrealistic goal. The concept of beneficence, viewed as a mandate, could also imply that defending oneself against a physical attack is unethical. Similarly, veracity, or truth telling, holds that one must always speak the truth regardless of the consequences. Therefore it is unethical to withhold potentially harmful information, regardless of the consequences. Adhering to veracity may interfere with one’s commitment to beneficence. Clearly, ethical standards taken as concrete directives do not allow for the consideration of context.

Ethical standards have been redefined, not as concrete rules, but as human qualities or character structures that can and must be recognized and respected in the individual (Husted & Husted, 1995b). For example, in symphonological terms, beneficence includes the idea of acting in the patient’s best interest, but it begins with the patient’s evaluation of what is beneficial. In this way, ethical standards are presuppositions in the health care professional–patient agreement and ethical guides to decision making. The participants work together with the implicit understanding that each is possessed of human characteristics. The description and names of the bioethical standards have changed over time based on feedback from practitioners. Symphonological theory holds that patients have a right to receive the benefits specified in the bioethical standards. Box 26.1 provides definitions and examples of bioethical standards.

Just as the bioethical standards are not to be considered as concrete directives, so too, they are not distinct entities. Each standard blends with the others as representative of the unique character structure of the individual (J. Husted, personal communication, March 2004). As stated earlier, recognition of these standards is preconditional to the implicit patient–health care professional agreement. When recognized and respected in each individual, these human qualities and capabilities form the basis for ethical interaction. When they are disregarded, the context of the situation is lost. Interaction is then based on whatever is served by concrete directives or on the whim of the participants.

Certainty

There are circumstances in health care when a patient is unable to communicate his unique character structure, as in the case of an infant or a comatose patient. Health care professionals also interact with individuals from different cultures for whom a common language is lacking. In these cases, the bioethical standards can provide a measure of certainty when knowledge of an individual’s unique character is unobtainable.

“If you know nothing whatever about an individual’s uniqueness, then you are justified in acting on the basis that, as a member of the human species, he shares much in common with every other individual”

(Fedorka & Husted, 2004, p. 58).

These commonalities are the bioethical standards. Each person needs the power to sustain his unique nature; the power to be objectively aware of his surroundings; and the power to control his time and effort, to pursue benefit, and to avoid harm. Lacking other information, nurses and health care professionals are justified to do all they can to restore these powers to the individual.

Decision-making model

Fig. 26.1 demonstrates the way the concepts of the theory interact with direct decision making. The elements of ethical decision making interact in the following way:

• A person is a rational being with a unique character structure. Each person has the right to choose and pursue, without interference, a course of action in accordance with his needs and desires.

• Agreements between individuals are demonstrated by a shared state of awareness directed toward a goal.

• The health care professional–patient agreement is directed toward preserving and enhancing the life of the patient.

• Context is the basis for determining what actions are ethical within the health care professional–patient agreement. “Context is the interweaving of the relevant facts of the situation—the facts that are necessary to act upon to bring about a desired result, an agent’s awareness of these facts, and the knowledge an agent has of how to deal most effectively with these facts” (Husted & Husted, 2008, p. 84). In this way, there are no universal ethical principles.

• Ethical decisions are the result of reasoning from the context to a decision rather than applying a decision or principle to a situation without regard for the context.

The Husteds described the ultimate application and practice of these assumptions by health care professionals in the following way. The professional will come to understand and work from the philosophy that:

“My patient’s virtues (autonomy) are such that he is moving toward his goal (freedom) in these circumstances (objectivity) for this reason (beneficence). My virtues (autonomy) are such that I must act with him (interactive freedom) to assist him (his freedom) within the possibilities (of beneficence) in his circumstances to achieve every possible benefit that can be discovered (by objective awareness).”

(Husted & Husted, 2001, p. 154)

Logical form

Abductive reasoning, like induction and deduction, follows a pattern:

• A is a collection of data (the process of discerning ethical action).

• B (if true) explains A (symphonology).

• No other hypothesis explains A as well as B does (traditional methods).

The strength of an abductive conclusion depends on how solidly B can stand by itself, how clearly B exceeds alternatives, how comprehensive was the search for alternatives, the cost of B being wrong and the benefits of being right, and how strong the need is to come to a conclusion at all (Josephson & Josephson, 1994).

The abductive method is evident in the inception and evolution of symphonology. The strength of this theory is evident as well. The concepts of symphonology clearly can be observed not only in health care but also in other walks of life. It is clear that ethical action based on the context of an individual’s particular circumstances is far superior to the imposition of concrete directives that often contradict one another or have little relationship to the situation at hand. The authors’ extensive study of the philosophy of knowledge, science, and the human condition attests to the comprehensive search for alternative answers. The benefit to patients and health care professionals of receiving practice-based ethical care would be immeasurable. Finally, the need to address the problem of how to achieve ethical action in health care could not be more critical.

Since the initial development of symphonology, inductive reasoning based on observation and feedback from practitioners has provided for refinement of the concepts and clarification of the relationships among concepts.

Acceptance by the nursing community

Practice

The Husted symphonological model for ethical decision making (Husted & Husted, 2001) was developed as a practice model for applying the concepts of symphonology. This model, stressing the centrality of the individual and the necessity of reason directed by context, is vital in existing and emerging health care systems. The model provides a philosophical framework to ensure ethical care delivery by nurses and all other disciplines of health care. Unlike traditional models, the symphonological model provides for logically justifiable ethical decision making. The North Memorial Medical Center in Robbinsdale, Minnesota, adopted the model for use by their nursing ethics committee.

The call to care in nursing is central to the profession. Hartman (1998) asserted that caring is demonstrated when nurses recognize that the bioethical standards are so intertwined with caring that together they provide a perfect circle of ethical justification. Enns and Gregory (2006) proposed that nursing is losing the essence and practice of caring because of the changing health care environment. Symphonology offers a practice-based approach to care, as follows:

“A practice-based approach is derived from, and therefore is intended to be appropriate to the situation of a patient, the purpose of the health care setting, and the role of the nurse. The more an ethical system restricts practice based on abstract principles the more nurse and patient become alienated from each other.”

(Husted & Husted, 1997b, p. 14)

Many nurses practice within systems bound by protocols and critical pathways. Using a symphonological approach can ensure that nursing practice remains ethical and does not become prescriptive. This is particularly important when considering making decisions for those who can no longer make decision for themselves (Gropelli, 2005). Often clinical emergency patients are unable to participate in decision making. Symphonology offers a method of ensuring that ethical conclusion and actions are based on the best interests of the individual (Fedorka & Husted, 2004).

Offering culturally sensitive care is increasingly important as our health care systems change in response to a global society (Chenowethm et al., 2006; Wehbe-Alamah, 2008; Zoucha & Broome, 2008). Although cultural factors can be helpful in directing care for a patient, nurses must also consider the individual’s personal commitment to the traditions and beliefs of his culture. In this way, the nurse provides care for the patient rather than the culture (Zoucha & Husted, 2000). Using the Husted model, care is directed within the context of the individual’s circumstances. Imposition of a false context, cultural or otherwise, is prevented. Brown (2001b) advocated the use of symphonology theory to direct discussion and education of patients regarding advance directives. Bioethical standards are used to guide discussion about what type of treatment an individual would or would not want, given particular circumstances. Hardt (2004) proposed an intervention for nurses in ethical dilemmas. The emergence of health care teams as a method of delivering comprehensive care brings many disciplines together to serve patients’ needs. Overlapping roles and disparate goals can cause confusion among team members. Symphonological theory, with its patient-centered focus, can serve as common ground to initiate and promote collaboration among health care professionals of all disciplines. Symphonology can be applied to all caring disciplines. Khechane (2008) developed a model for pastoral care practice based on symphonology. Using the decision-making model, pastoral care practitioners provide for the relief of suffering using the bioethical standards.

Education

As symphonology is disseminated, it is easy to integrate it into nursing education. Ethics is increasingly being addressed throughout nursing curricula rather than as a separate topic, particularly for advanced nursing students. The broad applicability for symphonology makes it an excellent framework for nursing curricula. Beginning students can easily grasp and apply the theoretical concepts. Using this theory as a basis for nursing interactions directs the student in ethical practice from the beginning of learning nursing practice. The concept of context can be used as the basis for assessment. The bioethical standards direct the student in choosing appropriate approaches, timing, and type of interventions for each patient. Because of the holistic approach and central concern for the patient, symphonology can be incorporated easily into existing nursing curricula.

Brown (2001a) addressed the importance of ethical interaction between nurse educator and student. The agreement in this case is more explicit, because both parties are more aware of the commitments and responsibilities. Recognizing the bioethical standards in both the educator and the student serves to direct ethical actions between them. Above all, the educator and student recall that the educator–student–patient agreement is central to the learning process.

The Husted model not only identifies and organizes professional values and ethical principles for learners, but it also helps the educator to develop a consistent professional ethical orientation. Cutilli (2009) used case study applications with the symphonological theory approach to patient and family education. Burger et al. (2014) used the Husted model to examine incivility among faculty in education. The model provides a mechanism to explore interactions based on the bioethical standards and facilitates ethical decision making within interactions. This led to the conclusion that the integration of ethics into academia is essential for nursing education.

Administration

Health care administrators make decisions at several levels. They have a responsibility to the community at large and the financial viability of the institution within the community, the employees, and those receiving care. Hardt (2004) described how administrators use the principles of symphonology to guide their decision making to produce ethically justifiable outcomes. At the community and institutional levels, one considers the needed services provided by the institution. In cases in which the services needed would not be feasible for the institution, resources within the community can be shared and supported by the institution so that needed services are available with the least amount of loss to the institution. At the employee level, the administrators are concerned with care delivery as well as interpersonal relations. Symphonology guides decision making into equitable rather than equal solutions. For example, an employer may choose to forgo the use of a harsh sanction for absenteeism when the employee is able to show extenuating circumstances that prevented her attendance. This is also true for the development of policy regarding employees’ behavior. Ethical policy provides guidelines for examining situations rather than prescribed rules with concrete directives for action. With regard to individual patients, administrators act as role models and consultants when addressing ethical issues.

Hardt and Hopey (2001) described the problematic situations that occur within managed care systems. Difficulties that have been identified include the refusal of the organization to provide care deemed appropriate by health care professionals and the inappropriate demands of patients and families. Using the principles of symphonology, health care professionals can examine the context and determine appropriate ethical actions within the implicit and explicit agreements.

Nurse administrators and managers can also use symphonology to mediate inappropriate situations between patients and nurses (Bavier, 2007)—for example, cases in which patients wish to give an inappropriate gift as a sign of appreciation to a particular nurse.

Research

Symphonology in research is useful in relation to the researcher-subject agreement. The health care professional–patient relationship is to some extent implicit, but the relationship between a researcher and a subject must be thoroughly explicit. Brown (2001c) suggested using the bioethical standards to develop an ethical informed consent protocol. Particularly when the research involves vulnerable populations, the consent of surrogates is made more acceptable and is obtained more easily if the good of the individual is made central by using the bioethical standards.

Further development

Initial testing of symphonological theory included two phases. First, a qualitative study examined the perceptions and satisfaction of nurses and patients and their significant others as they engaged in ethical decision making for health care issues (Husted, 2001). The themes that emerged from this study were used to develop visual analog tools to measure feelings in nurses and patients. In the second phase, a pilot study to test the tool was completed. The Cronbach alpha was reported as 0.74 for the nurse’s tool and 0.82 for the patient’s tool (Husted, 2004).

Irwin (2004) used a sample of 30 participants involved in a variety of decisions about health care and treatment during hospitalization in an acute care setting. The study included a decision support intervention for patients to determine the following: (1) whether key concepts of symphonological theory describe the experience of individuals making health care decisions, and (2) whether application of the decision-making framework enables nurses and patients to make ethically justifiable decisions. Results confirmed that patients expressed all the concepts of symphonology when discussing their experiences with health care decision making. Statistical analysis of pretest and posttest scores on the Bioethical Decision Making Preference Scale for Patients demonstrated that subjects had a more positive experience of being involved in decision making (p = 0.02) and felt more sufficiency of knowledge (p = 0.013), less frustration (p = 0.014), and more sense of power (p = 0.009) after the intervention. These findings support the validity of symphonology theory. The theory can be used to describe the experience of being involved in decision making, and symphonology has utility as a model for assisting patients through the decision-making process.

A graduate student used the nursing visual analog tool to discover how nurses felt when dealing with disclosure issues with patients and reported a Cronbach alpha of 0.82 (Bavier, 2003). Testing of the theory continues; a doctoral graduate analyzed data from a study designed to determine the effect of a symphonology-based educational intervention on the ethical decision-making performance of advanced-level nursing students and compared student understanding of the application of symphonology with other theories (Mraz, 2012).

Critique

Clarity

In Ethical Decision Making in Nursing (Husted & Husted, 1995a), the authors presented the emerging concepts of symphonology and the relationships among the concepts. The book may be difficult for beginning nurses to follow, because deeper concepts meant for advanced practitioners are included along with basic ideas. The third edition, Ethical Decision Making in Nursing and Healthcare: The Symphonological Approach, begins with the basic concepts for understanding and using the theory and then moves to more advanced concepts in later sections (Husted & Husted, 2001). Along with this improved organization, the third edition shows the emergence of increasing clarity for all concepts, the bioethical standards in particular. The fourth edition provides yet further clarity using tables and figures and includes a user-friendly teacher manual.

This work challenges traditional methods of thought and requires the reader to develop a new understanding of familiar concepts. Storytelling and examples provide the opportunity to recognize and understand the importance of alternative and extended meanings for familiar terms. The conversational tone of the writing is appealing and creates a comfortable atmosphere for a complex subject.

Simplicity

The authors first challenge the truth and efficacy of traditional ideas about ethical behavior and decision making. This is a simple matter if the reader is open-minded to a different view of nursing events. As the reader accepts the challenge, the simplicity of the theory is evident. There are few concepts, and the relational statements flow logically from the definitions. The model clearly demonstrates the elements of the process of ethical reasoning and the manner in which these elements interact.

Generality

Symphonology is applicable at all levels of nursing practice and in all areas of health care. The principles can be applied between nurse and patient, researcher and subject, manager and employee, and educator and student. Health care professionals of all types can use this method to determine appropriate ethical behaviors in practice. This theory can also be applied to the process of establishing health care policy that is ethical in nature. Indeed, these principles can be applied in all walks of life, depending on the nature of the agreement between the parties involved.

Accessibility

Symphonology is a theory grounded in ethical principles and based in reality. Evidence has demonstrated support of the theory in nursing practice decision research, and the reality of the usefulness of the theory in practice is evident. Nurses and other health care professionals can easily understand the concepts and apply them in all situations. The result of using the symphonological model is a patient-centered, ethically justifiable decision.

Importance

Being able to identify ethical actions in health care is of vital importance to patients, health care professionals, and the health care industry itself. Understanding ethical dilemmas of nursing practice is important for nursing education, research, and practice. Before a nurse or any health care professional takes action (regardless of how effective the action has been in the past), the action must be justified as ethical with regard to the particular patient. Reliance on concrete directives to guide action serves the directives, but only by chance serves the patient. Therefore the pursuit of a practice-based ethical theory is essential for nursing practice and health care.

Summary

The Husteds recognized that the traditional methods of decision making were insufficient to address the bioethical problems emerging in the evolving health care system. They developed a theory of ethics and a decision-making model based on rational thought combined with ethical principles, insight, and understanding. Their theory is founded on the singular concept of human rights, the essential agreement of nonaggression among rational people that forms the foundation of all human interaction. Upon this foundation, health care professionals and patients enter into an agreement to act to achieve the patient’s goals. Preconditional to this agreement are recognition and respect for each person’s unique character structure and the attendant properties of that structure: freedom, objectivity, beneficence, and fidelity. Ethical decisions are established within the context of a particular situation, using knowledge pertaining to the situation. Symphonological theory and the model for practice ensure ethically justifiable, individualized decisions.

Critical thinking activities

Using the Husted model, analyze the following ethical situations:

1. Christina, 46 years of age, has been in the hospital for 2 weeks after a traumatic injury. Her condition was very grave, but she is beginning to show signs of recovery. The health care team suggests that a blood transfusion will provide the necessary support to continue her improvement. Christina and her family practice a religious faith that does not permit blood transfusions. Christina’s husband and religious leader insist that she not be given the transfusion regardless of the consequences. When the visitors leave, Christina tells the nurse that she would like to receive the transfusion, but only if it could be kept secret from her family. What should the nurse do?

2. Angela, 34 years of age, is dying of lung cancer. Despite counseling and support, she is very frightened. When her death is imminent, she screams over and over, “Don’t let me die! Don’t let me die!” Despite all efforts, Angela succumbs before her husband arrives. He asks, “How was she? Was she afraid?” What should the nurse say?

3. Johnny, 7 years of age, is a psychiatric inpatient with a diagnosis of trichomania (hair pulling). His parents are very concerned about stopping his destructive behavior and have developed a series of punishments for incidents of hair pulling. Johnny has been seen pulling his hair out several times during the day. His parents arrive and ask how many times Johnny pulled his hair. What should the nurse say?

4. Eugene, 47 years of age, has several chronic illnesses. Despite education and support, he declines to adhere to prescribed health care practices. Mark, a home health care nurse, has been seeing Eugene for several months and has made little progress in helping Eugene improve his health. While discussing the situation, Eugene tells Mark that he has no intention of changing his behaviors. Is Mark justified in asking the physician to discontinue home health visits?

5. Agnes is a nurse on a busy medical nursing unit. Mr. Brown frequently asks Agnes to interrupt her work to answer questions and perform nonemergent tasks for him. Agnes’s other patients complain of neglect. What should Agnes do, and how can she justify her actions?

6. Burt, a 34-year-old manic depressive patient, lives in a group home with others. Sometimes, Burt stops taking his medication and disappears for weeks at a time. He has been arrested for vagrancy, but has never been violent. He states he enjoys his “vacations,” because his medicine makes his life seem boring, dull, and difficult. Burt’s family calls the director of the group home and insists that Burt be required to take his medicine each morning under supervision. What should the director say, and how could he justify various courses of action?

Points for further study

• Burger, K., Kramlich, D., Malitas, M., Page-Cutrara, K., & Whitfield-Harris, L. (2014). Application of the symphonological approach to faculty-to-faculty incivility in nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education, 53(10), 563–568.

• Husted, J., Husted, G., Scotto, C., & Wolf, K. (2015). Ethical decision making in nursing and healthcare (5th ed.). New York: Springer.