Pain in Older Persons

Introduction

Pain is highly prevalent in older people. Up to 40% of elders living independently (Thomas et al 2004) and 80% of those in institutional settings (Takai et al 2010) report pain. Similar to younger individuals, pain in older people is associated with significant psychological distress and impaired physical function (Parmelee 2005). Nonetheless, older patients are at risk for inadequate treatment (Yates et al 2002). Multiple interacting factors probably contribute to this, but inadequate assessment may be a primary barrier (Gagliese and Melzack 1997b). Although information regarding pain and aging is now more readily available, many gaps in our knowledge remain. In this chapter we describe the validity and reliability of popular pain scales for use in the assessment of older people. We then critically review the data regarding age differences in the experience of experimental, acute, and chronic cancer and non-cancer pain.

Assessment of Pain Across the Adult Life Span

Appropriate assessment is essential to both pain research and management. Pain that is not recognized cannot be treated, whereas treatment initiated without adequate assessment is potentially dangerous. A comprehensive pain assessment must consider the multiple interacting biopsychosocial factors that contribute to the experience of pain (Melzack and Wall, 1988). The age of the person being assessed is an important consideration because it may influence the selection and administration of tools, as well as the goals and outcomes of treatment. Age-related visual, auditory, or cognitive impairments can hinder completion of assessment protocols and must be accommodated (Mody et al 2008). In addition, older people may be less able than younger people to tolerate the burden of long assessment sessions, necessitating modification in protocols, such as completion of longer questionnaires over multiple sessions (Mody et al 2008).

Another age-related factor that must be considered is the presence and impact of co-morbid conditions, including core geriatric syndromes such as frailty, pressure ulcers, incontinence, falls, functional decline, and delirium (Inouye et al 2007). Co-morbidities are associated with polypharmacy (Inouye et al 2007), which may have a further impact on pain and function. Therefore, a comprehensive pain assessment should be sensitive to the distinct needs of older people and must include standardized and validated measures of co-morbidity, medication use, and cognitive, physical, and psychological function.

Measures of Pain Intensity

The most frequently assessed component of pain is intensity: how much it hurts. Most pain scales were designed for use in younger adults, but their use in older people has been a growing research focus. The data available support the use of the following pain intensity measures in older people: verbal descriptor scales (VDSs), numerical rating scales (NRSs), box scores, facial pain scales (FPSs), and pain thermometers. These scales have been associated with high completion rates, moderate to good concurrent and construct validity, and acceptable test–retest reliability (Herr et al 2004, Gagliese et al 2005, Peters et al 2007). There is evidence of comparable sensitivity across age groups for NRSs and FPSs (Gagliese and Katz 2003, Herr et al 2004). However, data regarding the sensitivity of VDSs are mixed (Gagliese and Katz 2003, Herr et al 2004). In addition, the construct validity of FPSs, that is, the extent to which they are interpreted as uniquely portraying pain rather than other physical symptoms or emotional states, may be inadequate in older people (Pesonen et al 2008).

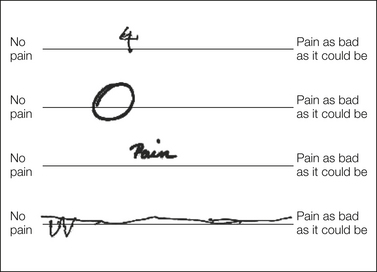

Caution is necessary when using visual analog scales (VASs) in older patients. Increasing age has been associated with a higher frequency of incomplete or unscorable responses (Fig. 22-1) (Herr et al 2004, Gagliese et al 2005, Peters et al 2007). These difficulties may be related to psychomotor and cognitive impairment (Herr et al 2004, Peters et al 2007). Among older people who can complete them, VASs show poor convergent validity, or lack of agreement with other intensity measures (Gagliese and Katz 2003, Herr et al 2004). In addition, they may not be sufficiently sensitive to detect age differences, although they may be as sensitive as other intensity measures to detect changes over time in older patients (Gagliese and Katz 2003). Finally, older patients report that VASs are more difficult to complete and are a poorer description of pain than other scales (Gagliese et al 2005). More research is needed to elucidate the cognitive demands of VASs and the ways in which performance may be affected by age.

The McGill Pain Questionnaire

The McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) measures the sensory, affective, evaluative, and miscellaneous dimensions of pain (Melzack 1975). Its psychometric properties are not age related: the latent structure, internal consistency, and pattern of subscale correlations are very similar in younger and older chronic pain patients who have been matched for gender, pain diagnosis, location, and duration (Gagliese and Melzack 2003). In addition, it is sufficiently sensitive for the assessment of age- and time-related changes in postoperative pain (Gagliese and Katz 2003). The short form of the MPQ (SF-MPQ) (Melzack 1987), which measures the sensory and affective dimensions of pain, has demonstrated good psychometric properties across the adult life span (Gagliese and Melzack 1997a, Strand et al 2008). Importantly, the same MPQ and SF-MPQ descriptors are chosen most frequently by different age groups to describe the same type of pain (e.g., arthritis pain) (Gagliese and Melzack 1997a, 2003), thus supporting the scales’ construct and discriminative validity.

In summary, NRSs, VDSs, and the MPQ are the best choices for pain intensity and quality measurement across the adult life span. As with younger patients, comprehensive assessment of older persons with pain should also include measures of physical disability, interference of pain in daily and/or desired activities, and psychological distress. Self-report and objective measures of many of these constructs are in frequent use in both research and the clinical setting (see review by Gauthier and Gagliese 2011).

Age Differences in Experimental Pain

Studies of age differences in pain threshold have been inconsistent, with reports that threshold increases, decreases, or does not change with increasing age (Gagliese and Farrell 2005). Similarly, both increased and decreased pain tolerance with age has been reported (Gagliese and Farrell 2005). These disparate findings may be the result, in part, of methodological weaknesses and diversity of the studies. For example, there is considerable variability in the mean age of the groups being compared, the pain induction methods used, and the psychophysical end points measured. Subject inclusion and exclusion criteria and sufficient statistical data to allow comparison across studies are often not provided. In addition, several studies do not include adequate numbers of older subjects. Despite these methodological limitations, the majority of studies indicate that there is an increase in the thermal and pressure pain threshold and a decrease in pain tolerance with age, but no change in sensitivity to electrical stimulation. There is also evidence of increased sensitivity to ischemic pain with age. The cross-modality differences in age-related patterns are not surprising given that each type of stimulation may engage slightly different neural processes, which may not be uniformly affected by aging.

Neurobiology of Pain and Aging

It is likely that the age differences just described are the end result of multiple, interacting neurobiological and behavioral factors. In the periphery, age-related changes in characteristics of the skin (Yaar et al 2002) and nociceptors (Guergova and Dufour 2011) may be important. In addition, both C-fiber (Namer 2010) and Aδ-fiber (Chakour et al 1996) functions decrease with age. Coupled with age-related changes in the neuroimmunological response to tissue injury (Ashcroft et al 2002), this may contribute to the decreased neuroplasticity evident throughout the central nervous system (Crutcher 2002). Consistent with this finding, when compared with younger people, older people show prolonged hyperalgesia (Zheng et al 2000), altered temporal summation (Harkins et al 1996, Edwards and Fillingim 2001), and impaired descending endogenous inhibition (Edwards and Fillingim 2001, Lariviere et al 2007) in response to experimental pain paradigms. Taken together, these findings suggest that adaptation to painful stimuli and injury may be impaired with advancing age, thereby possibly increasing vulnerability to persistent pain.

Recent imaging studies have shown that older people have smaller responses than younger people to thermal stimulation in several brain regions, including the primary somatosensory cortex, anterior insula, and supplementary motor area (Quiton et al 2007). However, a different pattern of age-related activation was found in response to pressure stimulation (Cole et al 2010). Importantly, there is preliminary evidence that older people with chronic pain may have structural brain changes when compared to older people without pain (Buckalew et al 2008). More research will be needed to further elucidate age- and pain-related patterns of brain activation in response to nociceptive stimulation and ongoing clinical pain.

The neurobiology of aging and its implications for pain sensitivity remain to be elucidated. Undoubtedly, there is an interaction of both peripheral and central changes, including changes in emotional and cognitive factors. Perhaps the patterns of age differences in pain reflect the differential effects of age on the integrity or activity levels of these systems. There is evidence that age-related changes in the neurobiological substrates of pain are not uniform throughout the central nervous system (Gagliese and Melzack 2000). Importantly, the implications of these changes for clinical painful states remain to be determined. Experimental pain paradigms provide an oversimplified approximation of both the acute and chronic pain experience, in part because the important role that psychological and emotional factors play in pathological pain states cannot be modeled in the experimental setting (Melzack and Wall 1988). The relevance of the mechanisms underlying differences in experimental pain reactivity must be evaluated in the clinical setting. It would not be surprising to find that the mechanisms vary across different types of pain.

Age Differences in Clinical Pain

Age-related patterns in the prevalence of pain are complex. Although many studies report that the prevalence of certain pain complaints peaks in middle age and decreases or plateaus thereafter (Andersson et al 1993, de Zwart et al 1997), there are also reports of age-related increases (Crook et al 1984), decreases (Mehta et al 2001), and stability (Thomas et al 2004) in the prevalence of various types of pain. These inconsistent results may reflect higher rates of mortality or institutionalization in older people with chronic pain, age differences in the willingness to report painful symptoms, and cross-study variability in the definitions of chronic and/or acute pain, as well as actual differences in the ways that the prevalence and incidence of various painful symptoms change with age. There is no a priori reason to expect all types of pain to change in a comparable fashion with age given the different pathophysiological mechanisms involved.

Regardless of the age-related patterns, a considerable proportion of older people experiences pain and pain at multiple sites is common (Tsai et al 2010). Pain may be especially prevalent in older nursing home residents, with up to 80% reporting at least one current pain problem and approximately 40% describing their pain as severe or intolerable (Takai et al 2010). Although further research is needed to clarify age-related prevalence patterns, older people clearly have a significant burden of pain.

Acute Pain

The most striking and consistently reported age differences are found in the experience of acute pain related to specific, brief pathological insults or infectious processes. Pathological conditions that are painful to young adults may, in older persons, produce only behavioral changes such as confusion, restlessness, aggression, anorexia, or fatigue (Peters 2010). When pain is reported, it is likely to be referred from the site of origin in an atypical manner. For example, although asymptomatic and atypical myocardial infarction is uncommon in younger patients, up to 30% of older survivors do not report acute symptoms, and another 30% have atypical findings (Mehta et al 2001). Mechanisms for the differences in acute pain with age are poorly understood (Moore and Clinch 2004). Importantly, these differences may contribute to delayed seeking of treatment, misdiagnosis, and increased mortality in older people (Mehta et al 2001, Peters 2010).

Postoperative Pain

Older people make up the largest group of surgical patients (Kemeny 2004), and they may be at greater risk than younger patients for unrelieved and prolonged postoperative pain (Melzack et al 1987, Gagliese and Katz 2003). Several studies have suggested that older patients report less pain than younger patients do (see review by Ip et al 2009), whereas others have not found age differences (Oberle et al 1990, Gagliese et al 2005). Although these discrepant results may be related to variability in cross-study methodology, it is also possible that they reflect the influence of unmeasured factors such as surgical and analgesic protocol, gender, and previous surgical experience (Gagliese et al 2008). Consistent with this, the correlates of postoperative pain may differ between younger and older patients (Gagliese et al 2008). Importantly, advancing age has been associated with impaired long-term recovery, including the development of chronic post-surgical pain (White et al 1997). This is consistent with data showing that almost 25% of older people referred to a multidisciplinary pain clinic report chronic post-surgical pain (Gagliese and Melzack, 2003). There is an urgent need for knowledge regarding age-related patterns in postoperative pain, analgesia, and recovery.

Cancer Pain

Cancer is primarily a disease of older persons, with almost 45% of new cases and 60% of deaths occurring in patients older than 70 years (National Cancer Institute of Canada 2006). Age differences in cancer pain are unclear, with decreases (Morris et al 1986, Cheung et al 2011), increases (Yates et al 2002, Torvik et al 2008), and no change (Vigano et al 1998, Barbera et al 2010) reported with age. This probably reflects cross-study variability in patient populations and pain assessment strategies. Regardless of age-related patterns, a large proportion of older patients experience significant pain. Up to 70% of older people with advanced disease report moderate to severe pain that interferes with quality of life (Stein and Miech 1993, Torvik et al 2008). Predictors of cancer pain in older people include younger age, female gender, advanced disease, no analgesic use, co-morbid conditions, lower social support, depressed mood, and lower physical functioning (Bernabei et al 1998, Given et al 2001).

Increasing age is a risk factor for inadequate cancer pain management (Cleeland et al 1994, Torvik et al 2008). More than two-thirds of hospitalized older cancer patients given opioids continue to report moderate to severe pain, thus suggesting inadequate dosing (Stein and Miech 1993). In the long-term care setting, 26% of older cancer patients who report daily pain do not receive any analgesics, with the oldest patients and those belonging to minority groups least likely to receive analgesics (Bernabei et al 1998). Studies are needed to examine factors that may have an impact on opioid use and efficacy, including adverse effects, gender, polypharmacy, and co-morbidity, as well as patient, health care worker, and systemic barriers (Yates et al 2002).

Chronic Non-cancer Pain

Many older people experience chronic non-cancer pain. Although most studies have not found age differences in the intensity of chronic non-cancer pain (Sorkin et al 1990, Rustoen et al 2005, Wittink et al 2006), an age-related decrease in MPQ scores is consistently reported (Gagliese and Melzack 1997b, 2003; Baker et al 2008). Among older people, risk factors for chronic non-cancer pain include female gender, lower education level, more co-morbid conditions, higher body mass index, and decreased physical function (Baker et al 2008, McCarthy et al 2009, Shega et al 2010).

The Cognitive Dimension of Chronic Pain

Cognitive factors, including beliefs about pain and the use of various coping strategies, have consistently been associated with pain intensity, disability, and emotional distress (Weisenberg 1999). It has been suggested that older people believe that pain is a normal part of aging and, as a result, may be stoic and reluctant to report symptoms or seek treatment (Yong 2006). However, a significant proportion of older people do not agree that pain is a normal part of aging (Brockopp et al 1996). Consistent with this finding, age differences in pain beliefs have not been found in younger and older pain-free individuals or in those with various types of chronic non-cancer pain (Strong et al 1992, Gagliese and Melzack 1997c). Furthermore, there do not appear to be age differences in treatment expectations, acceptance, compliance, or dropout rates (Sorkin et al 1990, Harkins and Price 1992), thus suggesting that older people who seek treatment do not believe that their pain is a natural, to-be-tolerated consequence of aging. It is possible that older people who seek treatment hold different beliefs about pain than those who do not seek treatment. This distinction is important and merits serious empirical attention, especially in light of evidence that older people may face barriers to effective pain treatment (Lansbury 2000). Cohort and generational effects undoubtedly heavily influence beliefs about symptoms and treatment seeking and must be considered in the interpretation of these results.

Older people with chronic pain have lower levels of catastrophizing, fear of pain, and pain avoidance than do middle-aged people with chronic pain (Cook et al 2006, Wittink et al 2006). In older people, fear avoidance is associated with pain intensity, range of motion, and functional abilities (Basler et al 2008). Importantly, fear of reinjury may play a more important role in depression and disability in older than in younger patients (Cook et al 2006, Wittink et al 2006), thus making it a potential target of cognitive behavioral interventions.

Subtle differences in the use of coping strategies for pain have also been reported. Older people are more likely than younger patients to use passive strategies such as praying or hoping (Keefe and Williams 1990, Sorkin et al 1990, Watkins et al 1999). These differences, however, are not large. Interestingly, the intensity of pain may be a critical factor. Although age differences may be evident when pain is mild to moderate, younger and older people with severe pain do not differ (Watkins et al 1999). In addition, perceived effectiveness of coping strategies and ability to control pain do not differ between age groups (Keefe and Williams 1990, Gagliese and Melzack 1997c, Wittink et al 2006). Overall, the pattern of coping strategies seems more similar than dissimilar across age groups (Sorkin et al 1990).

The Affective Dimension of Chronic Pain

Older people with chronic non-cancer pain report better mental health than do younger people with chronic pain when broad-based measures of mental health or well-being are used (Rustoen et al 2005, Wittink et al 2006). However, when depression-specific measures are used, prevalence and intensity are similar across age groups (Sorkin et al 1990, Turk et al 1995, Gagliese and Melzack 2003). This may reflect conceptual differences in these measurement approaches. Importantly, up to 40% of older people with chronic pain report clinically relevant symptomatology (Lopez-Lopez et al 2008). Older people with chronic pain obtain higher scores on depression scales than do those who are pain free (Wang et al 1999), and depressed older people report more intense pain and have more pain complaints than do non-depressed older people (Casten et al 1995). In prospective studies, pain is a risk factor for the onset of depression in older people, especially older men (Geerlings et al 2002). In addition, suicide risk may be elevated in older people with moderate to severe pain, especially men with multiple medical co-morbidities (Juurlink et al 2004). Screening for depression, including suicidal ideation, is a priority in the assessment of older people with chronic pain.

Chronic Pain and Impairment

Both chronic pain and increasing age (Forbes et al 1991) are associated with impairment in functional abilities and performance of activities of daily living. Older people with chronic pain are at greater risk than younger people for pain-related physical disability (Wittink et al 2006, Bryant et al 2007). They also report more disability than pain-free older people do (Scudds and Robertson 2000). This may be exacerbated by co-morbid conditions, especially mild cognitive impairment (Shega et al 2010). Interestingly, the predictors of pain-related disability may vary with age. Specifically, affective distress may be an important predictor of disability in younger, but not older, people with chronic pain, whereas pain severity may be a predictor in older, but not younger patients (Edwards 2006). Therefore, assessment and prevention of pain-related disability may need to target the most relevant constructs for different age groups of patients. Taken together, it is clear that a large proportion of older people experience chronic non-cancer pain, which has a detrimental impact on all aspects of quality of life. Importantly, effective pain management may improve these outcomes (Bryant et al 2007).

Pain and Dementia

The relationship of dementia-related neurodegeneration to pain prevalence, incidence, intensity, and impairment has received increased empirical attention. Experimental pain thresholds do not differ between cognitively impaired and intact older people (Gibson et al 2001). Similarly, the proportion of older people who report chronic non-cancer pain does not differ by cognitive status (Shega et al 2010). However, differences in the intensity of painful conditions remain unclear (Scherder et al 1999, Shega et al 2010). It is difficult to interpret these findings because memory and language impairments may confound reports of pain unrelated to any actual changes in the experience (Farrell et al 1996). Importantly, older people with dementia are at greater risk than those who are cognitively intact for undertreatment of pain (Morrison and Siu 2000, Scherder and Bouma 2000, but see Bell et al 2011).

It has been proposed that the neuropathology associated with dementia changes the experience of pain (Scherder et al 2003). The directionality of these changes is not obvious. Damage to different brain areas has been associated with both increases and decreases in pain intensity and affect (Melzack and Wall 1988). Consistent with this, different types of dementia may be associated with unique changes in pain related to the area, extent, and etiology of the brain damage (Scherder et al 2003). Preliminary evidence that cognitive impairment is associated with changes in brain responses to noxious stimulation is available (Benedetti et al 1999, Gibson et al 2001, Cole et al 2010); however, more research is needed to adequately address this issue.

Altered autonomic nervous system responses to painful stimuli have also been reported. When compared with cognitively intact people, those with impairment show blunted heart rate and blood pressure responses to mild noxious stimuli (Porter et al 1996, Benedetti et al 1999, Rainero et al 2000). Interestingly, they show less arousal in anticipation of painful stimulation, but subsequently, in response to the actual painful stimulation, they may show greater facial expressiveness and behavioral reactivity than cognitively intact patients do (Porter et al 1996, Rainero et al 2000, Kunz et al 2009). This may be related to generalized disinhibition rather than pain perception per se (Porter et al 1996). Taken together, these studies suggest that there may be a myriad of factors involved in the possible alteration of pain in older people with dementia. At present, there is insufficient evidence to draw any firm conclusions. Furthermore, these results must be interpreted with great caution because the most reliable and valid pain assessment protocol for use with this group has yet to be identified.

Only preliminary evidence is available regarding the use of self-report scales by people with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. Although many patients are unable to complete these measures (Ferrell et al 1995, Feldt et al 1998), training with careful, repeated explanation of the task may improve performance (Chibnall and Tait 2001, Closs 2004). Not surprisingly, VASs are especially problematic in this population (Closs 2004).

As dementia progresses, self-report becomes impossible, and it is necessary to rely on the observation of pain behavior or facial expressions. Clinically, valuable information may be obtained from significant others (Werner et al 1998) or through direct observation (Weiner et al 1996), especially abrupt changes in behavior or usual functioning. More than 20 behavioral checklists have been developed for this group, and consistent with the guidelines of the American Geriatrics Society, many assess facial expression, vocalizations, body movements, and changes in interpersonal interactions, activity patterns or routines, and mental status (Bjoro and Herr 2008, While and Jocelyn 2009). However, recent reviews have concluded that most lack sufficient validation and that none can be strongly recommended over the others (Bjoro and Herr 2008, While and Jocelyn 2009). Identification of the best measurement tool for use with this vulnerable group is a research priority.

Conclusion

There has been an increase in the empirical attention devoted to pain in older people. As a result, we are beginning to appreciate the complexity of age-related patterns across different types of pain and subgroups of older people. Consequently, many directions for future research become evident. For instance, the data available are suggestive of interesting interactions between the neurobiology of aging and the neurobiology of pain, a topic that requires further investigation. Another important issue is pain in the most vulnerable seniors: those who are cognitively impaired and unable to verbally communicate their pain. Finally, longitudinal studies are needed to identify predictors of the development of chronic pain and subsequent morbidity. Despite the many gaps in our knowledge, it is clear that intense pain that interferes with functioning is not a normal part of aging and should never be accepted as such. It is hoped that future studies will resolve some of the inconsistencies highlighted throughout this chapter. This knowledge will be invaluable to the growing number of older people and those committed to their care.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Breast Cancer Research Association and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to LG.

The references for this chapter can be found at www.expertconsult.com.

References

Andersson H.I., Ejilertsson G., Leden I., et al. Chronic pain in a geographically defined population: Studies of differences in age, gender, social class and pain localization. Clinical Journal of Pain. 1993;9:174–182.

Ashcroft G.S., Mills S.J., Ashworth J.J. Ageing and wound healing. Biogerontology. 2002;3:337–345.

Baker T.A., Buchanan N.T., Corson N. Factors influencing chronic pain intensity in older black women: examining depression, locus of control, and physical health. Journal of Women’s Health. 2008;17:869–878.

Barbera L., Seow H., Howell D., et al. Symptom burden and performance status in a population-based cohort of ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2010;116:5767–5776.

Basler H.D., Luckmann J., Wolf U., et al. Fear-avoidance beliefs, physical activity, and disability in elderly individuals with chronic low back pain and healthy controls. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2008;24:604–610.

Bell J.S., Laitinen M., Lavikainen P., et al. Use of strong opioids among community-dwelling persons with and without Alzheimer’s disease in Finland. Pain. 2011;152:543–547.

Benedetti F., Vighetti S., Ricco C., et al. Pain threshold and tolerance in Alzheimer’s disease. Pain. 1999;80:377–382.

Bernabei R., Gambassi G., Lapane K., et al. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:1877–1882.

Bjoro K., Herr K. Assessment of pain in the nonverbal or cognitively impaired older adult. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2008;24:237–262.

Brockopp D., Warden S., Colclough G., et al. Elderly people’s knowledge of and attitudes to pain management. British Journal of Nursing. 1996;5:556–562.

Bryant L.L., Grigsby J., Swenson C., et al. Chronic pain increases the risk of decreasing physical performance in older adults: the San Luis Valley health and aging study. Journals of Gerontology. Series A. Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2007;62:989–996.

Buckalew N., Haut M.W., Morrow L., et al. Chronic pain is associated with brain volume loss in older adults: preliminary evidence. Pain Medicine. 2008;9:240–248.

Casten R.J., Parmelee P.A., Kleban M.H., et al. The relationships among anxiety, depression, and pain in a geriatric institutionalized sample. Pain. 1995;61:271–276.

Chakour M.C., Gibson S.J., Bradbeer M., et al. The effect of age on A delta- and C-fibre thermal pain perception. Pain. 1996;64:143–152.

Cheung W.Y., Le L.W., Gagliese L., et al. Age and gender differences in symptom intensity and symptom clusters among patients with metastatic cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2011;19:417–423.

Chibnall J.T., Tait R.C. Pain assessment in cognitively impaired and unimpaired older adults: a comparison of four scales. Pain. 2001;92:173–186.

Cleeland C.S., Gonin R., Hatfield A.K., et al. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;330:592–596.

Closs S.J. A comparison of five pain assessment scales for nursing home residents with varying degrees of cognitive impairment. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2004;27:196–205.

Cole L.J., Farrell M.J., Gibson S.J., et al. Age-related differences in pain sensitivity and regional brain activity evoked by noxious pressure. Neurobiology of Aging. 2010;31:494–503.

Cook A.J., Brawer P.A., Vowles K.E. The fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: validation and age analysis using structural equation modeling. Pain. 2006;121:195–206.

Crook J., Rideout E., Browne G. The prevalence of pain complaints in a general population. Pain. 1984;18:299–314.

Crutcher K.A. Aging and neuronal plasticity: lessons from a model. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic & Clinical. 2002;96:25–32.

de Zwart B.C.H., Broersen J.P.J., Frings-Dresen M.H.W., et al. Musculoskeletal complaints in the Netherlands in relation to age, gender and physically demanding work. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 1997;70:352–360.

Edwards R.R. Age differences in the correlates of physical functioning in patients with chronic pain. Journal of Aging and Health. 2006;18:56–69.

Edwards R.R., Fillingim R.B. Effects of age on temporal summation of thermal pain: clinical relevance in healthy older and younger adults. Journal of Pain. 2001;2:307–317.

Farrell M.J., Katz B., Helme R.D. The impact of dementia on the pain experience. Pain. 1996;67:7–15.

Feldt K.S., Ryden M.B., Miles S. Treatment of pain in cognitively impaired compared with cognitively intact older patients with hip-fracture. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1998;46:1079–1085.

Ferrell B.A., Ferrell B.R., Rivera L. Pain in cognitively impaired nursing home residents. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1995;10:591–598.

Forbes W.F., Hatward L.M., Agwani N. Factors associated with the prevalence of various self-reported impairments among older people residing in the community. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 1991;82:240–244.

Gagliese L., Farrell M.J. The neurobiology of ageing, nociception and pain: an integration of animal and human experimental evidence. In: Gibson S.J., Weiner D.K., eds. Progress in pain research and management: pain in the older person. Seattle: IASP Press; 2005:25–44.

Gagliese L., Gauthier L.R., Macpherson A.K., et al. Correlates of postoperative pain and intravenous patient-controlled analgesia use in younger and older surgical patients. Pain Medicine. 2008;9:299–314.

Gagliese L., Katz J. Age differences in postoperative pain are scale dependent: a comparison of measures of pain intensity and quality in younger and older surgical patients. Pain. 2003;103:11–20.

Gagliese L., Melzack R. Age differences in the quality of chronic pain: a preliminary study. Pain Research and Management. 1997;2:157–162.

Gagliese L., Melzack R. Chronic pain in elderly people. Pain. 1997;70:3–14.

Gagliese L., Melzack R. Lack of evidence for age differences in pain beliefs. Pain Research and Management. 1997;2:19–28.

Gagliese L., Melzack R. Age differences in nociception and pain behaviours in the rat. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24:843–854.

Gagliese L., Melzack R. Age-related differences in the qualities but not the intensity of chronic pain. Pain. 2003;104:597–608.

Gagliese L., Weizblit N., Ellis W., et al. The measurement of postoperative pain: a comparison of intensity scales in younger and older surgical patients. Pain. 2005;117:412–420.

Gauthier L.R., Gagliese L. Assessment of pain in older persons. In: Turk D.C., Melzack R., eds. Handbook of pain assessment. ed 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2011:242–259.

Geerlings S.W., Twisk J.W.R., Beekman A.T.F., et al. Longitudinal relationship between pain and depression in older adults: sex, age and physical disability. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2002;37:23–30.

Gibson S.J., Voukelatos X., Ames D., et al. An examination of pain perception and cerebral event-related potentials following carbon dioxide laser stimulation in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and age-matched control volunteers. Pain Research & Management. 2001;6:126–132.

Given C.W., Given B., Azzouz F., et al. Predictors of pain and fatigue in the year following diagnosis among elderly cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2001;21:456–466.

Guergova S., Dufour A. Thermal sensitivity in the elderly: a review. Ageing Research Reviews. 2011;10:80–92.

Harkins S.W., Davis M.D., Bush F.M., et al. Suppression of first pain and slow temporal summation of second pain in relation to age. Journals of Gerontology. Series A. Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 1996;51A:M260–M265.

Harkins S.W., Price D.D. Assessment of pain in the elderly. In: Turk D.C., Melzack R., eds. Handbook of pain assessment. New York: Guilford Press; 1992:315–331.

Herr K.A., Spratt K., Mobily P.R., et al. Pain intensity assessment in older adults—use of experimental pain to compare psychometric properties and usability of selected pain scales with younger adults. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2004;20:207–219.

Inouye S.K., Studenski S., Tinetti M.E., et al. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:780–791.

Ip H.Y.V., Abrishami A., Peng P.W.H., et al. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:657–677.

Juurlink D.N., Herrmann N., Szalai J.P., et al. Medical illness and the risk of suicide in the elderly. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164:1179–1184.

Keefe F.J., Williams D.A. A comparison of coping strategies in chronic pain patients in different age groups. Journals of Gerontology. Series B. Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1990;45:161–165.

Kemeny M.M. Surgery in older patients. Seminars in Oncology. 2004;31:175–184.

Kunz M., Mylius V., Scharmann S., et al. Influence of dementia on multiple components of pain. European Journal of Pain. 2009;13:317–325.

Lansbury G. Chronic pain management: a qualitative study of elderly people’s preferred coping strategies and barriers to management. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2000;22:2–14.

Lariviere M., Goffaux P., Marchand S., et al. Changes in pain perception and descending inhibitory controls start at middle age in healthy adults. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2007;23:506–510.

Lopez-Lopez A., Montorio I., Izal M., et al. The role of psychological variables in explaining depression in older people with chronic pain. Aging & Mental Health. 2008;12:735–745.

McCarthy L.H., Bigal M.E., Katz M., et al. Chronic pain and obesity in elderly people: results from the Einstein Aging Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57:115–119.

Mehta R.H., Rathore S.S., Radford M.J., et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: differences by age. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001;38:736–741.

Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–299.

Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30:191–197.

Melzack R., Abbott F.V., Zackon W., et al. Pain on a surgical ward: a survey of the duration and intensity of pain and the effectiveness of medication. Pain. 1987;29:67–72.

Melzack R., Wall P.D. The challenge of pain. London: Penguin Books; 1988.

Mody L., Miller D.K., McGloin J.M., et al. Recruitment and retention of older adults in aging research. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:2340–2348.

Moore A.R., Clinch D. Underlying mechanisms of impaired visceral pain perception in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:132–136.

Morris J.N., Mor V., Goldberg R.J., et al. The effect of treatment setting and patient characteristics on pain in terminal cancer patients: a report from the national hospice study. Journal of Chronic Disease. 1986;39:27–35.

Morrison R.S., Siu A.L. A comparison of pain and its treatment in advanced dementia and cognitively intact patients with hip fracture. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2000;19:240–248.

Namer B. Age related changes in human C-fiber function. Neuroscience Letters. 2010;470:185–187.

National Cancer Institute of Canada. Toronto: Canadian cancer statistics; 2006.

Oberle K., Paul P., Wry J., et al. Pain, anxiety and analgesics: a comparative study of elderly and younger surgical patients. Canadian Journal on Aging. 1990;9:13–22.

Parmelee P. Measuring mood and psychosocial function associated with pain in late life. In: Gibson S.J., Weiner D.K., eds. Progress in pain research and management: pain in the older person. Seattle: IASP Press, 2005.

Pesonen A., Suojaranta-Ylinen R., Tarkkila P., et al. Applicability of tools to assess pain in elderly patients after cardiac surgery. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2008;52:267–273.

Peters M. The older adult in the emergency department: aging and atypical illness presentation. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2010;36:29–34.

Peters M.L., Patijn J., Lame I. Pain assessment in younger and older pain patients: psychometric properties and patient preference of five commonly used measures of pain intensity. Pain Medicine. 2007;8:601–610.

Porter F.L., Malhorta K.M., Wolf C.M., et al. Dementia and the response to pain in the elderly. Pain. 1996;68:413–421.

Quiton R.L., Roys S.R., Zhuo J., et al. Age-related changes in nociceptive processing in the human brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1097:175–178.

Rainero I., Vighetti S., Bergamasco B., et al. Autonomic responses and pain perception in Alzheimer’s disease. European Journal of Pain. 2000;4:267–274.

Rustoen T., Wahl A.K., Hanestad B.R., et al. Age and the experience of chronic pain: differences in health and quality of life among younger, middle-aged, and older adults. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2005;21:513–523.

Scherder E.J., Bouma A. Acute versus chronic pain experience in Alzheimer’s disease. A new questionnaire. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2000;11:11–16.

Scherder E.J., Bouma A., Borkent M., et al. Alzheimer patients report less pain intensity and pain affect than non-demented elderly. Psychiatry. 1999;62:265–272.

Scherder E.J., Sergeant J.A., Swaab D.F., et al. Pain processing in dementia and its relation to neuropathology. Lancet Neurology. 2003;2:677–686.

Scudds R.J., Robertson J.M. Pain factors associated with physical disability in a sample of community-dwelling senior citizens. Journals of Gerontology. Series A. Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2000;55:M393–M399.

Shega J.W., Paice J.A., Rockwood K., et al. Is the presence of mild to moderate cognitive impairment associated with self-report of non-cancer pain? A cross-sectional analysis of a large population-based study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2010;39:734–742.

Shega J.W., Weiner D.K., Paice J.A., et al. The association between noncancer pain, cognitive impairment, and functional disability: an analysis of the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Journals of Gerontology. Series A. Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2010;65:877–883.

Sorkin B.A., Rudy T.E., Hanlon R.B., et al. Chronic pain in old and young patients: differences appear less important than similarities. Journals of Gerontology. Series B. Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1990;45:64–68.

Stein W.M., Miech R.P. Cancer pain in the elderly hospice patient. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1993;8:474–482.

Strand L.I., Ljunggren A.E., Bogen B., et al. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire as an outcome measure: test-retest reliability and responsiveness to change. European Journal of Pain. 2008;12:917–925.

Strong J., Ashton R., Chant D. The measurement of attitudes towards and beliefs about pain. Pain. 1992;48:227–236.

Takai Y., Yamamoto-Mitani N., Okamoto Y., et al. Literature review of pain prevalence among older residents of nursing homes. Pain Management Nursing. 2010;11:209–223.

Thomas E., Peat G., Harris L., et al. The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: cross-sectional findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Pain. 2004;110:361–368.

Torvik K., Holen J., Kaasa S., et al. Pain in elderly hospitalized cancer patients with bone metastases in Norway. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2008;14:238–245.

Tsai Y.F., Liu L.L., Chung S.C. Pain prevalence, experiences, and self-care management strategies among the community-dwelling elderly in Taiwan. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2010;40:575–581.

Turk D.C., Okifuji A., Scharff L. Chronic pain and depression: role of perceived impact and perceived control in different age cohorts. Pain. 1995;61:93–101.

Vigano A., Bruera E., Suarez-Almazor M.E. Age, pain intensity, and opioid dose in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 1998;83:1244–1250.

Wang S.J., Liu H.C., Fuh J.L., et al. Comorbidity of headaches and depression in the elderly. Pain. 1999;82:239–243.

Watkins K.W., Shifren K., Park D.C., et al. Age, pain, and coping with rheumatoid arthritis. Pain. 1999;82:217–228.

Weiner D., Peiper C., McConnell E., et al. Pain measurement in elders with chronic low back pain: traditional and alternative approaches. Pain. 1996;67:461–467.

Weisenberg M. Cognitive aspects of pain. In: Wall P.D., Melzack R., eds. Textbook of pain. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:345–358.

Werner P., Cohen-Mansfield J., Watson V., et al. Pain in participants of adult day care centers: assessment by different raters. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1998;15:8–17.

While C., Jocelyn A. Observational pain assessment scales for people with dementia: a review. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2009;14:438–442.

White C.L., LeFort S.M., Amsel R., et al. Predictors of the development of chronic pain. Research in Nursing & Health. 1997;20:309–318.

Wittink H.M., Rogers W.H., Lipman A.G., et al. Older and younger adults in pain management programs in the United States: differences and similarities. Pain Medicine. 2006;7:151–163.

Yaar M., Eller M.S., Gilchrest B.A. Fifty years of skin aging. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. Symposium Proceedings. 2002;7:51–58.

Yates P.M., Edwards H.E., Nash R.E., et al. Barriers to effective cancer pain management: a survey of hospitalized cancer patients in Australia. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2002;23:393–405.

Yong H.H. Can attitudes of stoicism and cautiousness explain observed age-related variation in levels of self-rated pain, mood disturbance and functional interference in chronic pain patients? European Journal of Pain. 2006;10:399–407.

Zheng Z., Gibson S.J., Khalil Z., et al. Age-related differences in the time course of capsaicin-induced hyperalgesia. Pain. 2000;85:51–58.

Benedetti F., Vighetti S., Ricco C., et al. Pain threshold and tolerance in Alzheimer’s disease. Pain. 1999;80:377–382.

Bernabei R., Gambassi G., Lapane K., et al. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:1877–1882.

Buckalew N., Haut M.W., Morrow L., et al. Chronic pain is associated with brain volume loss in older adults: preliminary evidence. Pain Medicine. 2008;9:240–248.

Chakour M.C., Gibson S.J., Bradbeer M., et al. The effect of age on A delta- and C-fibre thermal pain perception. Pain. 1996;64:143–152.

Cook A.J., Brawer P.A., Vowles K.E. The fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: validation and age analysis using structural equation modeling. Pain. 2006;121:195–206.

Edwards R.R., Fillingim R.B. Effects of age on temporal summation of thermal pain: clinical relevance in healthy older and younger adults. Journal of Pain. 2001;2:307–317.

Gagliese L., Melzack R. Chronic pain in elderly people. Pain. 1997;70:3–14.

Gagliese L., Melzack R. Age differences in nociception and pain behaviours in the rat. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24:843–854.

Guergova S., Dufour A. Thermal sensitivity in the elderly: a review. Ageing Research Reviews. 2011;10:80–92.

Inouye S.K., Studenski S., Tinetti M.E., et al. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:780–791.

Mehta R.H., Rathore S.S., Radford M.J., et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: differences by age. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001;38:736–741.

Moore A.R., Clinch D. Underlying mechanisms of impaired visceral pain perception in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:132–136.

Morrison R.S., Siu A.L. A comparison of pain and its treatment in advanced dementia and cognitively intact patients with hip fracture. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2000;19:240–248.

Peters M.L., Patijn J., Lame I. Pain assessment in younger and older pain patients: psychometric properties and patient preference of five commonly used measures of pain intensity. Pain Medicine. 2007;8:601–610.

Quiton R.L., Roys S.R., Zhuo J., et al. Age-related changes in nociceptive processing in the human brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1097:175–178.

Scherder E.J., Sergeant J.A., Swaab D.F., et al. Pain processing in dementia and its relation to neuropathology. Lancet Neurology. 2003;2:677–686.

Scudds R.J., Robertson J.M. Pain factors associated with physical disability in a sample of community-dwelling senior citizens. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2000;55:M393–M399.

Sorkin B.A., Rudy T.E., Hanlon R.B., et al. Chronic pain in old and young patients: differences appear less important than similarities. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1990;45:64–68.

Takai Y., Yamamoto-Mitani N., Okamoto Y., et al. Literature review of pain prevalence among older residents of nursing homes. Pain Management Nursing. 2010;11:209–223.

Turk D.C., Okifuji A., Scharff L. Chronic pain and depression: role of perceived impact and perceived control in different age cohorts. Pain. 1995;61:93–101.

Vigano A., Bruera E., Suarez-Almazor M.E. Age, pain intensity, and opioid dose in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 1998;83:1244–1250.