4

Medication Administration

After completing this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

1. Define terms and abbreviations related to medication administration.

2. Identify the role of the surgical technologist in medication administration.

3. Explain the five “rights” of medication administration.

4. List and discuss the steps of medication identification used in surgery.

5. Explain aseptic techniques for delivery of medications to the sterile field.

6. Describe the procedure for labeling drugs on the sterile back table.

7. Discuss how to properly handle medications.

8. Identify supplies used in medication administration in surgery.

9. Discuss standard precautions and sharps safety in relation to medication administration.

The role of the surgical technologist in medication administration varies from state to state and differs from facility to facility. As a surgical technologist, you should have firsthand knowledge of medication administration legislation in your state.

Institutional policies and procedures regarding medication handling and administration should be clearly understood as well. All staff members have a duty to know and adhere to established medication policies and procedures. Handling medications is a critical function in the surgical technologist’s job description. Several different types of medications are obtained and passed to the surgeon routinely during a procedure, and the surgical technologist must be knowledgeable regarding such drugs.

Surgical Technologist’s Roles in Medication Administration

Administration of drugs from the sterile field is a team effort. Each team member has a particular role in the process (Box 4-1). Most commonly, medications used from the sterile field are obtained by the circulator (a nonsterile team member) and delivered to the scrub person (a sterile team member). The scrub person is responsible for passing the medication to the surgeon for administration during the surgical procedure. Each team member is responsible for accurately identifying all medications used from the sterile field during a surgical procedure.

Circulating Role

The surgical technologist in the circulating role obtains medications as specified on the surgeon’s preference card, delivers those medications to the sterile field as needed, and documents the medications used from the sterile field during an operation. The circulator must be sure that the medication obtained is the exact drug and strength specified on the preference card. The circulator must also inspect the container for integrity and expiration date. The circulator must maintain strict sterile technique when transferring medications to the scrub person. All medications must be properly identified, both by the scrub and by the circulator. The circulator is responsible for documenting all medications used from the sterile field according to institutional policy.

Scrub Role

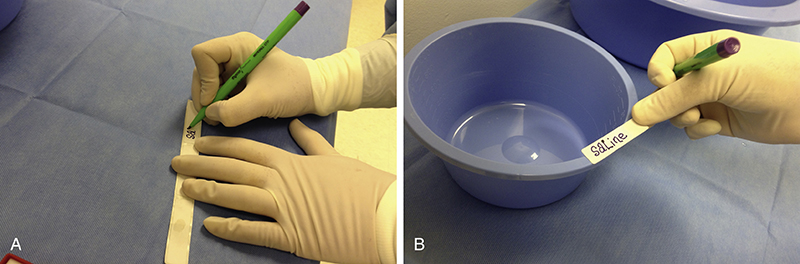

The surgical technologist in the scrub role correctly identifies and accepts medications from the circulator, immediately labels (Fig. 4-1) those medications, and passes medications to the surgeon, as requested. Accurate identification and immediate labeling of all drugs accepted onto the sterile field are crucial. If medications are not clearly identified, they should be discarded immediately and a new dose should be obtained. This practice is essential to avoid possible drug administration error. The surgical technologist must clearly state the name and strength of a medication when passing it to the surgeon.

The Five “Rights” of Medication Administration

The five “rights” of medication administration have been established to help avoid medication errors (Box 4-2). Team members must work together to ensure that the right drug is given in the right dose, by the right route, to the right patient, and at the right time. It is also important to ensure that all medications given are accurately documented.

Right Drug

Drugs that are routinely needed on the sterile field during a procedure should be clearly specified on the surgeon’s preference card. The information is initially obtained directly from the surgeon and entered into the electronic preference card by a qualified member of the surgery department staff. Electronic preference cards are one component of computer software programs used in surgery, and the format may vary by institution. The information stated on the preference card must be accurate, including correct spelling and strength. If handwritten preference cards are used, information must be written legibly to avoid confusion. Preference cards should be updated as needed to reflect any changes in routine medications. Additional drugs are obtained in response to verbal orders by the surgeon during the procedure.

In addition, some medications used in surgery, such as Depo-Medrol and Solu-Medrol (two brand names for methylprednisolone, see Chapter 8), are easily confused because they may sound similar. Other drugs may have similar spellings, such as Tobrex and TobraDex (see Chapter 10). The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) maintains a list of confused drug names, which includes look-alike and sound-alike name pairs and serves as a resource for clinical practice. The surgical technologist must always clarify the name of the requested medication if there is any doubt.

When any medication is delivered to the sterile back table, it must be carefully identified by both the circulator and scrub and labeled immediately and accurately by the scrubbed surgical technologist. All medication containers must be labeled, including delivery container (such as a syringe) and intermediate containers (often a medicine cup or basin). Careful, mindful attention must be consistently practiced in the identification and labeling of drugs to prevent medication errors.

The scrub person must always state the name and strength of the drug aloud as he or she hands it to the surgeon; this practice serves as confirmation that the medication is correct. The name of the drug should be spoken aloud even though the syringe (or other delivery container) is labeled. Using two processes, audible and visual, provides an additional level of patient safety. If there is ever any question as to the identity of a medication on the back table, it must be discarded and a new dose of the intended medication must be obtained, identified, and labeled.

Right Dose

The actual dose of a medication is a factor of both its amount (volume) and its strength (concentration), which is explained in more detail in Chapter 1 (Insight 1-2). For example, you might see an order for 30 mL (amount) of 0.5% (strength) lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000 on a surgeon’s preference card. This information must be clearly specified and clearly understood. It is especially important when the drug must be mixed or diluted on the sterile back table. For example, suppose a surgeon requests 0.5 mL of 1% phenylephrine (Neo-Synephrine) diluted in 20 mL of saline for vasoconstriction. Further suppose that 1% phenylephrine is available in 1 mL vials only. If the entire 1-mL vial (instead of the 0.5 mL specified) is mixed with the correct amount (20 mL) of saline and dispensed to the sterile field, the dosage of phenylephrine administered will be twice the desired dose.

Written protocols may be instituted and posted to eliminate common confusions about some medications. Heparin (a systemic anticoagulant) is an excellent example of a medication that is available in a number of different strengths in the same volume (see Chapter 9). During insertion of a venous access port, different strengths of heparin may be needed from the sterile back table: 100 units/mL and 10 units/mL may be used, each concentration with a specific purpose. Given the tenfold difference in heparin concentration, immediate, accurate, and complete labeling is crucial (Fig. 4-2). In addition, the scrubbed surgical technologist must understand the reasons or purposes for the various strengths of heparin required to know which concentration to hand at the appropriate time. In this case a department routine or protocol for heparin dosages in venous access procedures may be established and posted to minimize the potential for error.

The surgical technologist serves a key role in the prevention of administration of the wrong dosage of a medication from the sterile field. In addition to ensuring correct identification and labeling, the scrubbed surgical technologist provides the final safety check for intended dosage by stating out loud and clearly the name and strength of the medication as it is handed to the surgeon.

Right Route

Most medications administered in surgery are given intravenously, usually by the anesthesia care provider. However, many other medications may be injected or applied topically by the surgeon at the surgical site. Different administration routes may require different preparations and concentrations of a medication. The preference card should clearly state administration route or form, so that the proper form of the drug for a particular route may be obtained. For example, the preference card for cystoscopy may state that 2% lidocaine jelly is needed for local anesthesia (see Chapter 14). Although the preference card should clearly state “for topical application,” it may also be safely assumed that properly educated surgical team members know that jelly, a semisolid form of the drug, is intended for topical application, not injection (Fig. 4-3). In a situation of a novice practitioner or a person with a knowledge deficit, careful reading of the medication label will reveal that this form of lidocaine is intended for topical use only. This situation also provides an excellent example of the importance of always reading the medication label carefully. When in doubt, the surgical technologist must clarify the information stated on the preference card.

Another common example demonstrating the use of the right form of a drug for the right route is 1% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000 for local anesthesia for procedures such as breast biopsy. Again the administration route may not be stated clearly on the preference card because the drug specified is formulated for injection. If for some unusual reason a team member does not know that a local anesthetic agent is injected for breast biopsy, careful reading of the medication label will provide the necessary information.

Another common medication, Cortisporin (see Chapter 5), is specifically formulated for administration by two different routes used in surgery. Cortisporin Ophthalmic is formulated for administration into the eye, and Cortisporin Otic is intended for use in the external ear canal (Fig. 4-4). The surgical technologist must read the drug label carefully to ensure that the correct form of this drug is available for the intended administration route.

FIGURE 4-3 Syringe prefilled with 2% lidocaine hydrochloride (HCl) jelly. (Courtesy Sheryl Olson. In Auerbach PS: Wilderness medicine, ed 6, St Louis, 2012, Elsevier.)

FIGURE 4-4 Cortisporin otic label. (From Morris DG: Calculate with confidence, ed 5, St. Louis, 2010, Elsevier.)

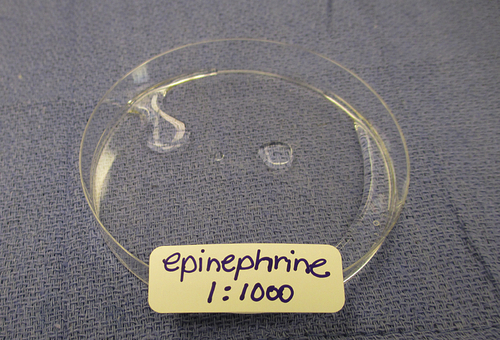

A crucial example of the importance of the right dose for the right route in surgery occurs during procedures on the middle ear. The surgical technologist must exercise particular caution when identifying, labeling, and handling medications for middle ear surgery because two significantly different strengths of epinephrine (a hormone that is a powerful vasoconstrictor, see Chapter 8) are present on the sterile back table. For example, in tympanoplasty, epinephrine 1:1000 is administered on tiny pieces of Gelfoam (see Chapter 9) for topical hemostasis in the middle ear, whereas a local anesthetic with dilute epinephrine (1% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000 or 1:200,000) is injected for hemostasis over a larger area. Both solutions are used for hemostasis but in significantly different strengths intended for significantly different routes. In addition, both solutions are clear. For the correct medication to be passed at the correct time, both solutions must be accurately identified and labeled, and the surgical technologist must know the route of administration for both strengths of epinephrine. If epinephrine 1:1000 is mistakenly injected, deadly tachycardia and hypertension may result (Insight 4-1).

The scrubbed surgical technologist must observe the delivery of these medications to the sterile field and immediately label each drug—its identity and strength—as it is accepted into the sterile field to avoid errors. In addition, topical-strength epinephrine (1:1000) must never be kept in a syringe on the back table. Rather, a shallow container (such as a sterile Petri dish) should be used for topical epinephrine to prevent the drug from being mistakenly drawn up into a syringe for injection.

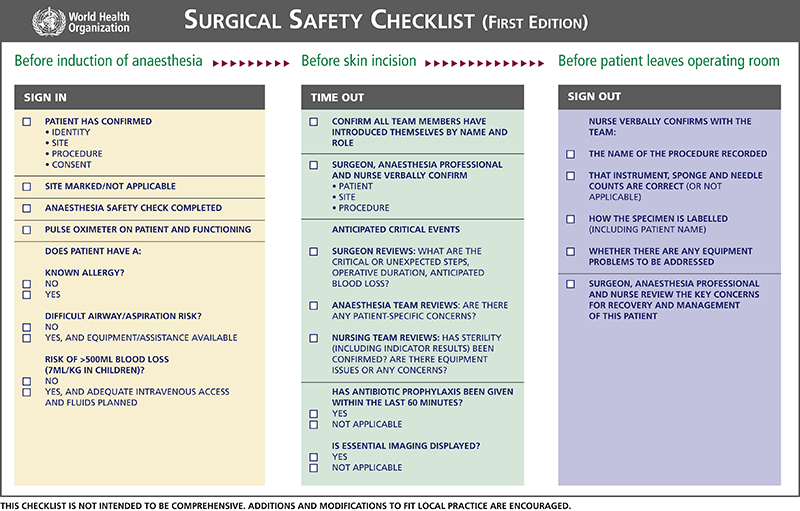

Right Patient

All surgical patients must be accurately identified before being transported into the operating room. Tools, such as The Joint Commission’s Universal Protocol and the World Health Organization’s Surgical Safety Checklist (Fig. 4-5), are used in The operating room to ensure that the correct surgical procedure will be performed on the correct patient. This process also includes relevant information about the patient, such as a history of drug allergies or hypersensitivity to a particular drug. The surgical procedure and operating surgeon are verified, and the preference card containing medication orders for that specific procedure is kept available in the operating room for reference. In addition, a surgical safety “time out” is conducted just before the incision to further verify that the intended surgical procedure is being performed on the correct patient. Diligence and care taken to properly identify the patient will help to ensure that the correct patient receives the medications intended for administration during a surgical procedure.

Right Time

In surgery the surgeon (or as delegated to the surgical first assistant) administers all medications at the surgical site. This practice prevents the vast majority of medication timing errors during surgery (for drugs administered from the sterile back table). The purpose of the drug, when stated on the preference card, often indicates the timing of administration. For example, if 1% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000 is listed on the preference card for a local anesthetic, it will be administered before incision. In addition, it may be administered periodically throughout the procedure as needed (pro re nata [PRN]) for patient comfort. If 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine 1:100,000 is listed on the preference card for postoperative pain control, it may be administered at the beginning of the procedure or at the time of wound closure. Some routine medications (e.g., contrast media for cholangiography, antibiotics for irrigation, heparinized saline) are obtained and labeled during case setup and passed to the surgeon at the appropriate time. The surgeon may request a drug by verbal order during any procedure. In such case the medication is obtained, labeled, and passed to the surgeon from the sterile back table for administration as soon as requested.

FIGURE 4-5 The World Health Organization’s Surgical Safety Checklist. (WHO, 2015, available at www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/ss_checklist/en/.)

Right Documentation

Traditionally there are five “rights” of medication administration: right drug, right dose, right route, right patient, and right time. It is also crucial, though, that medications given from the sterile table be accurately recorded in the operative record. The circulator will document all medications delivered to the field, and the surgical technologist in the scrub role will verbally provide a final total of the amount of each medication administered for the circulator to note in the record. When a medication is repeatedly administered during a procedure, such as a local anesthetic, the scrubbed surgical technologist must also maintain an accurate ongoing total of the amount of medication being used throughout the procedure.

Medication Identification

Both the scrub and the circulator are responsible for correctly identifying medications delivered to and used from the sterile field. This dual responsibility minimizes the potential for errors in medication administration, as does following a logical series of steps (Box 4-3) to properly identify drugs. The first step in medication identification is to carefully read the label on the medicine container (see Chapter 2 for examples of medication labels). The team member obtaining the drug reads the label initially and checks the container for cracks or discolored contents. If there is any doubt as to the integrity of the container, the medication should not be used. Rather, it should be returned to the pharmacy with a note indicating the specific concern. The medication label contains important information about the drug, as Table 4-1 shows. The most crucial information is the drug name (both generic and trade), strength, amount, and expiration date. Special handling instructions (such as refrigeration or keeping medication from direct light), the drug form, and intended administration route are also key pieces of drug information contained on the label (for more detail see Chapter 2 and Fig. 4-6). The circulator reads vital label information aloud just before delivery to the sterile field and shows the label to the surgical technologist in the scrub role. Finally, the scrub repeats the label information aloud to confirm the correct drug. The drug should be delivered to the sterile field only after the steps described have been completed. Alternatively, both scrub and circulator may read the information aloud together before delivery of the medication to the sterile field.

TABLE 4-1

Sample Information Contained on a Medication Label

| Type of Information | Example |

| Name (brand and generic) | bupivacaine HCl (Sensorcaine) |

| Strength | 0.5% |

| Amount | 50 mL |

| Expiration date | 01/2019 |

| Administration route | Injection |

| Manufacturer | AstraZeneca |

| Storage directions | Store at room temperature |

| Warnings or precautions | Federal law prohibits dispensing without prescription |

| Lot number | 1234567 |

| Schedule (only if drug is a controlled substance) | (C-I to C-V, see Chapter 2) |

Delivery to the Sterile Field

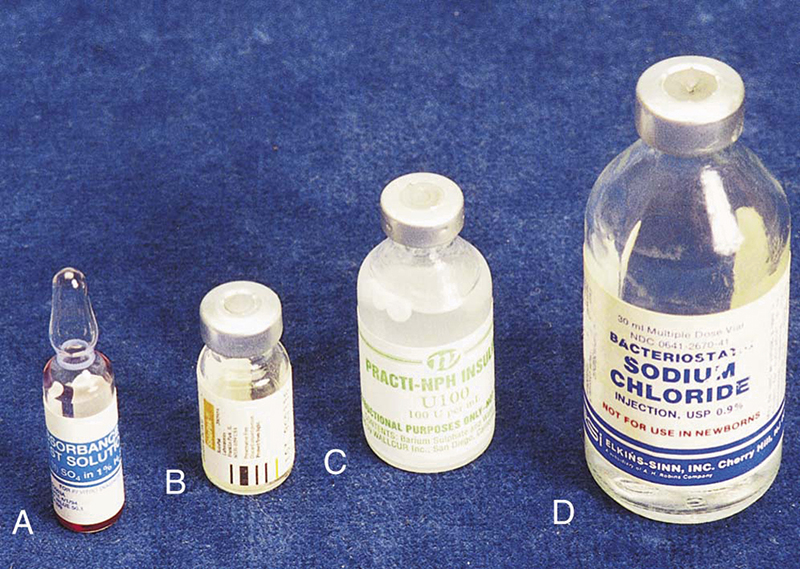

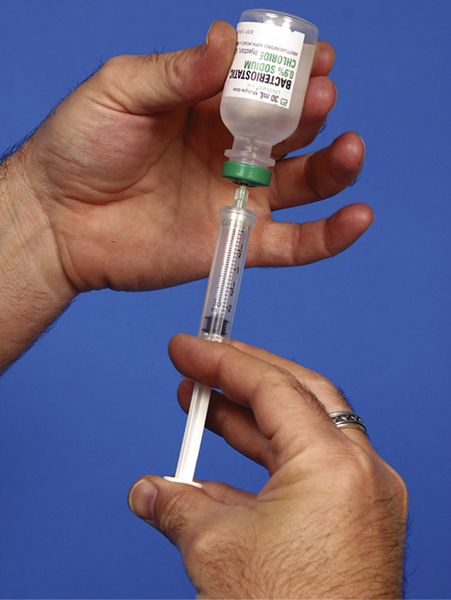

Principles of asepsis (sterile technique) must be followed when delivering and receiving medications into the sterile field. Medications frequently used from the sterile back table are packaged in different types of containers, including vials and ampules (Fig. 4-7), and aseptic delivery methods vary by type of container. One of the most common containers is a glass or plastic vial with a rubber stopper encased in a metal cap and covered by an outer plastic cap. The plastic cap is popped off without touching the rubber stopper underneath. The circulator can draw up the drug (if in liquid form) with a syringe and hypodermic needle and then empty the contents of the syringe into a sterile medicine cup held by the scrub. The circulator should handle only the outside of the vial and should not touch the rubber stopper unless it is being removed. Alternatively, the circulator may hold the vial in an inverted position while the scrub withdraws the drug from the vial with a syringe and needle (Fig. 4-8). The scrubbed surgical technologist should first draw some air into the syringe, then puncture the rubber stopper with the needle and inject air into the vial, which will allow the contents of the vial to enter the syringe rapidly. In addition, the hypodermic needle used to puncture the vial should be a larger needle, such as 18 gauge, to permit rapid filling of the syringe. After the medication is in the syringe, the 18-gauge needle is removed and replaced with the correct gauge needle for injection (such as a 25-gauge needle).

FIGURE 4-6 A, Label showing special handling instructions. B, Label showing specific storage requirements. (From Macklin D, Chernecky CC, and Infortuna MH: Math for clinical practice, ed 2, St Louis, 2011, Elsevier.)

If a drug is in powder form in a vial, the circulator must reconstitute it, and the resulting liquid is withdrawn from the vial with a syringe and delivered to the sterile field, as described earlier.

FIGURE 4-7 Medication vials and ampule. (From Fulcher EM, Fulcher RM, Soto CD: Pharmacology: principles and applications, ed 3, St Louis, 2013, Elsevier.)

FIGURE 4-8 The scrubbed surgical technologist may draw up medication from a vial held by the circulator. (From Clayton BD, Willihnganz M: Basic pharmacology for nurses, ed 16, St Louis, 2013, Elsevier.)

If a syringe is used to draw up and inject the reconstituting agent and to withdraw the mixture, extra care must be taken not to touch the sides of the plunger (Fig. 4-9). If unsterile hands touch the plunger, the plunger contaminates the inside of the barrel as it moves down the barrel when injecting. If the drug mixture is then drawn into the syringe barrel, it too becomes contaminated.

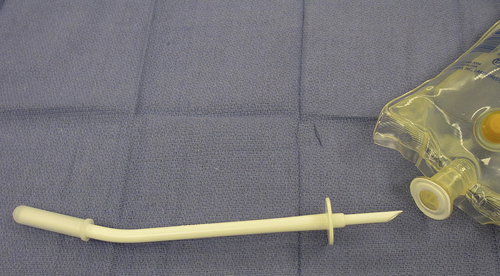

Sterile disposable spouts are commercially available to facilitate sterile delivery of medications contained in vials and in bags of intravenous solution (Fig. 4-10). Medications may be added to a bag of intravenous solution, such as a gram of an antibiotic into 1000 mL of normal saline, and disposable spouts called bag decanters are used to deliver the solution to the sterile field aseptically. Vial decanters are used to deliver medications contained in vials. Decanters provide a greater margin of safety by increasing the distance between the circulator (nonsterile person) and the scrubbed surgical technologist during medication delivery. If decanters are not available, the circulator should draw up the medication from the vial as described previously. Pouring directly from a vial into a sterile medication cup is discouraged because it is extremely difficult to verify that the rubber stopper was removed in a manner that did not contaminate any area of the vial lip.

FIGURE 4-9 Unsterile hands must not touch the syringe plunger. (From Fulcher EM, Fulcher RM, Soto CD: Pharmacology: principles and applications, ed 3, St. Louis, 2012, Saunders.)

FIGURE 4-10 A sterile, disposable pour spout (decanter) is used to deliver medication contained in a bag of intravenous fluid. The bag decanter is grasped by the hub, and the prong is inserted into the injection port on the bag.

FIGURE 4-11 Breaking an ampule. Carefully break the neck of the ampule in a direction away from you. (From Lilley LL, Collins SR, and Snyder JS: Pharmacology and the nursing process, ed 7, St Louis, 2014, Elsevier.)

Some medication vials and ampules are available in sterile packages, which can be opened directly onto the sterile field. The scrub is responsible for showing the medication label and expiration date to the circulator before opening the vial and drawing up the contents. Alternatively, the scrub may pour a medication directly from a sterile vial into a sterile medication cup within the sterile field.

Some medications are available in an ampule, a sealed glass container with a narrowed neck. The top of an ampule is broken off at the neck, and a sterile needle attached to a syringe is inserted to aspirate and withdraw the medication. Special care should be used when breaking the glass ampule because glass may cut unprotected hands. Plastic protective caps are available for this purpose and should be used to prevent injury during opening. A glass ampule should be broken away from the body to help to prevent injury from the broken edge (Fig. 4-11). Some glass ampules also come packaged sterile for use on the back table, such as the liquid component used to make polymethylmethacrylate (bone cement). Once again, care must be taken to protect the gloved hands. After the ampule is broken, the item used to protect the hands should be discarded from the sterile field to avoid accidental transfer of glass particles into the surgical wound.

Although not technically considered a medication, saline irrigation is often delivered to the sterile field from a pour bottle. The bottle cap should be lifted straight up and off, and the entire contents poured immediately. Unused portions should not be saved for later use because sterility cannot be ensured. If the bottle is recapped, its contents are considered unsterile because of potential contamination of the bottle lip during replacement of the cap.

FIGURE 4-12 A medication intended for topical application, such as epinephrine 1:1000, should be kept in a shallow container, such as a Petri dish, rather than a syringe. For example, Gelfoam pledgets are dipped into topical epinephrine (1:1000) for hemostasis in the middle ear.

To avoid potential contamination, the circulator must take care not to lean over the sterile field when delivering medications or solutions. The scrub should hold containers away from the sterile table when accepting medications to assist the circulator in maintaining a safe distance from the field.

Several different types of containers are available to store medications and solutions on the sterile back table (see Fig. 3-7). Medicine cups, pitchers, basins, or syringes may be used, depending on the volume of medication needed.

Medications intended for topical administration (such as thrombin or epinephrine 1:1000) should never be kept in a syringe on the back table. Syringes are used to inject medications. Some topical medications are fatal if injected. Use a labeled shallow container, such as a plastic Petri dish, to store topical medications. The use of a shallow container will make it more difficult to accidentally draw up a topical medication into a syringe. In addition, a shallow container provides easy access to the medication when needed (e.g., when dipping pieces of Gelfoam into the medication for topical application) (Fig. 4-12).

Medication Labeling on the Sterile Back Table

Once a medication has been delivered to the sterile back table, it is no longer in its original container, so it must be labeled immediately. Most drugs used from the sterile field are clear in color; thus they are easily confused if not clearly marked. There are different methods of labeling medications on the sterile back table, but the most important point is that each medication must be labeled—in the intermediate storage container (such as pitcher or medicine cup) and in any delivery vehicle (such as a syringe). The Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goal 3, NPSG.03.04.01, requires that all medication containers in the sterile field be labeled. The most accurate medication labeling method is the use of preprinted medication labels available from sterile supply manufacturers (Fig. 4-13). If preprinted labels are not available, a sterile skin marking pen may be used to write on blank labels. If blank labels are not available, sterile skin adhesive strips may be used. Regardless of the labeling method used, proper identification of all medications in the sterile field is an absolutely crucial step in preventing medication administration errors.

Occasionally the scrubbed surgical technologist may be replaced during a procedure (e.g., for shift change or lunch relief). All medications must be plainly labeled and reported to the new scrub. If there is any doubt as to the identity of a solution, it must be discarded and new medication must be obtained.

There is no acceptable excuse for the presence of unlabeled (unidentified) medications on the sterile back table. Improper or inadequate labeling of drugs may be considered negligent. Negligence is defined in the Miller-Keane Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing and Allied Health as “failure to do something that a reasonable person of ordinary prudence would do in a situation or the doing of something that such a person would not do.” By this definition it is “reasonable” to expect that the correct medication will be obtained, identified, and passed to the surgeon and that a “prudent” person will perform these duties. This means that reason and prudence are everyone’s responsibility, whatever the situation. This is not always easy. The rapid pace of events in surgery often pressures team members to accomplish difficult tasks in a hurry. However, the process of medication identification should never be compromised, nor should staff become complacent about routine medications. If a question or doubt arises regarding a medication, it must be clarified and resolved immediately. If the medication seems wrong or the dose appears to be incorrect, verify it with the physician before using it. It is better to be certain about the drug—even if it means provoking the surgeon—than to make an error and thus cause harm to the patient.

Handling Medications

When medications have been delivered to the sterile field and labeled, some additional handling may be necessary. Occasionally the surgeon may order that two medications be mixed for concurrent administration. For example, an anti-inflammatory agent and a long-acting local anesthetic agent may be mixed for injection into a joint at the conclusion of an arthroscopy. Some medications may be diluted before use, such as Hypaque (a radiopaque contrast medium, see Chapter 6), which may be diluted with equal parts of injectable saline as ordered on the preference card. It is vital that the surgical technologist read the preference card carefully and use basic math skills (see Chapter 3) to ensure the correct mixture or dilution of medications at the sterile back table. All containers (such as medicine cups) must be labeled for the original medications, and a separate container must be clearly labeled indicating the mixture or diluted medication. The administration container, usually a syringe, must be labeled with complete information on the mixture or dilution. The final check for accuracy is performed when the scrubbed surgical technologist states the complete mixing or dilution information when handing the medication to the surgeon.

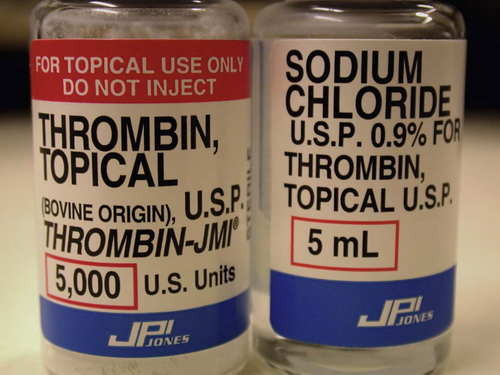

Other medications may require reconstitution before use (see Chapter 9). An example is topical thrombin, which is available in a sterile kit with a spray nozzle (Fig. 4-14). The kit contains a vial of thrombin, a vial of diluent (an inert diluting agent; saline), and a syringe with spray nozzle. The scrub draws the diluent into a syringe and injects it into the thrombin vial. The mixture is shaken until the thrombin is dissolved and drawn into the syringe. The nozzle is attached to enable administration to large oozing surfaces, such as the liver.

FIGURE 4-14 Topical thrombin is available as a spray pump, to be applied with a syringe, or as a reconstituted powder to saturate absorbable Gelfoam. (From Dockery GD, Crawford ME: Lower extremity soft tissue & cutaneous plastic surgery, ed 2, Edinburgh, 2012, Elsevier, Ltd.)

Special caution is required when handling controlled substances in surgery. Institutional policies regarding handling and disposal of controlled substances (see Table 2-1) must be in compliance with federal law; thus policies must be understood and followed by all staff members.

Supplies

Syringes and hypodermic needles are used frequently in surgery to draw up, measure, and administer medications. A syringe has three basic parts: the barrel (or outer portion), plunger (inside portion), and tip. The barrel of the syringe is marked or calibrated to indicate the amount of medication contained in the syringe. The amount of medication in the syringe is measured from the innermost edge of the rubber tip on the end of the plunger. The most common sizes of syringes routinely used in surgery range from 1 to 60 mL. Some syringes have a finger-control attachment on the barrel and plunger to provide ease of motion and more precise control when injecting (Fig. 4-15). The most common type of syringe tip used in surgery is the Luer-lock tip, which has a screw-type locking mechanism used to securely attach a hypodermic needle. Plain-tip or “slip-tip” syringes are also available, but these are used for specific purposes. For example, a plain-tip syringe may be attached to a spinal needle for subclavian venipuncture during a venous access procedure. Various sizes of syringes are used for various purposes, so consult the surgeon’s preference card for specific information. In general, 1-mL (called a TB or tuberculin syringe) and 3-mL syringes are used to inflate the tiny balloon on the end of an embolectomy catheter. By far the most common syringe size used in the operating room is a 10-mL syringe. That size syringe is used for a number of purposes, including inflating the cuff on a tracheostomy tube and injection of a local anesthetic agent throughout a surgical procedure. Thirty-milliliter syringes are most frequently used to inject saline irrigation and contrast media into the common bile duct, inflate a 30-mL balloon on a Foley catheter, or administer heparinized saline through an arterial irrigation catheter.

FIGURE 4-15 Types of syringes.

A, A 10-mL finger-control Luer-lock syringe. B, A 10-mL Luer-lock syringe. C, A 1-mL plain-tip tuberculin syringe.

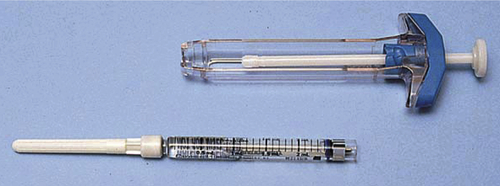

Special syringes are available for particular purposes. For example, a Tubex syringe has a metal or plastic device used to accommodate a carpule of medication for injection (such as lidocaine or heparin). A carpule is a glass tube with a rubber cap that is penetrated by a special needle attached to the Tubex syringe (Fig. 4-16). Another type of special syringe is a dual-syringe device used to deliver two medications simultaneously, such as those used to form a fibrin sealant (see Chapter 9).

FIGURE 4-16 A Tubex syringe, glass carpule, and needle. (From Potter P, Perry A: Basic nursing: essentials for practice, ed 5, St. Louis, 2003, Mosby.)

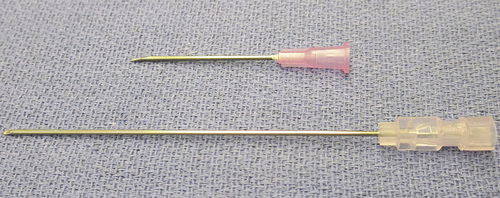

Hypodermic needles are used to draw up and administer drugs. A hypodermic needle has three basic parts: the hub (which fits onto a syringe), shaft, and tip (the beveled end of the shaft). Needles vary in diameter (gauge) and length (measured in inches). The larger the gauge of a needle, the smaller the diameter of the lumen (inside channel). Thus an 18-gauge needle has a much larger lumen than a 25-gauge needle. Most hypodermic needles used in surgery are disposable and are color-coded by size at the plastic hub for ease in identification. Sizes of hypodermic needles routinely used in surgery range from 27-gauge needles (used in ophthalmology) to larger 18-gauge needles (used to draw up medications). Color-coding for size may vary by manufacturer, but several companies use the same colors to indicate size. The three needle sizes most frequently used at the sterile field are 18 gauge (pink), 22 gauge (gray), and 25 gauge (blue). The most common hypodermic needle length used in surgery is 1½ inches (Fig. 4-17). Shorter, ⅝-inch needles may be used for superficial injections, whereas longer needles (3-inch), called spinal needles, may be used from the sterile field for specific purposes, such as aspiration of cysts or to inject fluid to distend the shoulder joint for a shoulder arthroscopy.

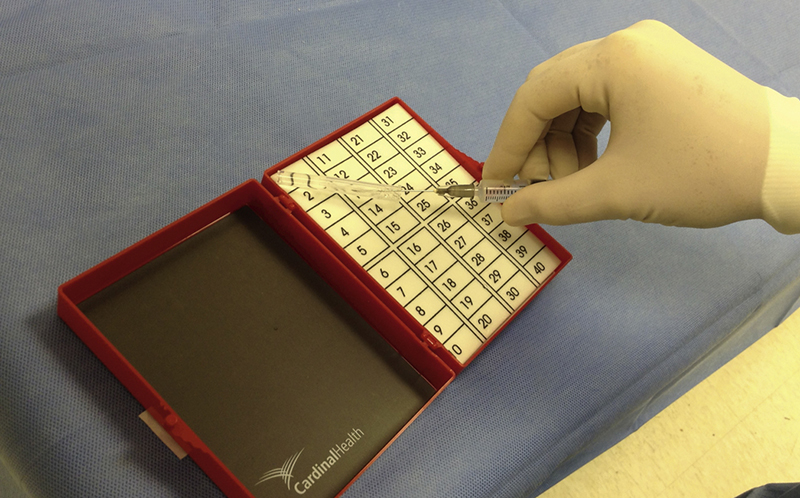

Sharps Safety

Standard precautions state that used needles must never be recapped because most needle-puncture injuries are the result of attempting to recap a used needle. It is also dangerous, though, to leave an unsheathed hypodermic needle exposed on the sterile table during a surgical procedure. Use of syringes and needles within the sterile field differs from other situations in that the same syringe and needle combination may be used repeatedly during the course of a surgical procedure. An example is the use of local anesthesia during a breast biopsy when the agent is administered into progressively deeper tissue layers to enable deeper dissection. For prevention of injury from the needle while not in use, it must be recapped between injections. In addition, more than 10 mL of local anesthetic may be required, which necessitates refilling of the syringe. For the refilling of a syringe at the sterile field, the smaller hypodermic needle used for injection is recapped, removed from the syringe, and replaced with a larger needle to draw up additional amounts of the agent. The larger needle is then recapped, removed from the syringe, and replaced with the smaller needle for injection. Both situations require recapping of hypodermic needles at the sterile field. To prevent injury, the surgical technologist must use a one-handed recapping technique (Fig. 4-18) or a recapping device intended for that purpose. Specialized self-shielding needles are also available for use from the sterile field (AST, 2017).

Learning the Language (Key Terms)

Using your textbook or a standard medical dictionary, look up and write the definitions of each term.

carpule

diluent

Advanced Practices for the Surgical First Assistant Chapter 4—Medication Administration

Key Terms

efficacy

half-life

potency

Five More “Rights” of Medication Administration

The five rights to medication administration are described in this chapter. Their importance for patient safety is reflected by frightening statistics. A medical error is defined by the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCCMERP) as “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer.” The reality is that serious preventable medication errors are estimated to occur in more than 3.2 million inpatient admissions and 3.3 million outpatient visits in the United States each year. Inpatient costs are approximately $16.4 billion and outpatient costs are estimated at $4.2 billion annually. The Institute of Medicine estimated 7000 deaths occur annually because of preventable medication errors. These statistics verify that five additional “rights” of medication administration are important for providing patient safety. The surgical first assistant may not be the primary professional involved in the actual medication administration; however, he or she can assist with clarifying and verifying information before, during, and after a medication is given. These five additional “rights” are the right patient assessment before administration, right documentation of the medication given, patient’s right to education about the medication before it is administered, right evaluation of the medication’s effect, and patient’s right to refuse the medication.

Medication Administration from the Sterile Field

Intraoperative administration of medications to the surgical patient presents a unique situation unlike any other medical environment, especially for the advanced practitioner functioning as a surgical first assistant. Different personnel administer medications to the patient through several routes, often at the same time. Although the surgical first assistant might not perform the actual administration of medications, it is important that he or she be aware of the effects any medication can have on the patient.

Personnel who fulfill the role of the surgical first assistant will have different educational and clinical backgrounds ranging from medical school to physician’s assisting, nursing, and surgical technology. These different backgrounds and employment disciplines dictate different regulatory agencies under which each professional practices in regard to administration of medications. State statutes will supersede any other regulatory agency in regard to limitations of practice; however, when there is no statute regulating specific personnel, it is usually the individual facility that regulates the practice. All personnel practicing as surgical first assistants should be aware of the policies or bylaws regulating their practice. For example, the surgical first assistant functioning as an independent practitioner may be regulated by the medical staff bylaws of the facility. However, the surgical first assistant employed by the facility may be regulated by that facility’s policies and procedures.

The process of administering medications at the sterile field requires a team effort. Medications will pass through at least two other people, the circulator and scrub person, before being delivered to the surgeon. The medication will almost always be in a container different from its original—usually a syringe, medicine cup, basin, or pitcher on the field. For the prevention of medication errors, strict policies and procedures have been developed for delivery of medications onto the sterile field (as described in this chapter). The surgeon and the surgical first assistant may be the last line of defense to avoid medication errors; therefore each should be aware of and follow all of these procedures. The person who administers the medication always has the right to question the procedure and decide whether the medication will be given or a new medication obtained. It is always in the best interest of the patient to discard any questionable medication (see Box 4-A).

Drug-Response Relationships

As discussed in Chapter 1, all medications have systemic effects on the patient. It is important for the surgical first assistant to be aware of these effects as well as the duration and safe dosages of medications. This pharmacological principle is known as the dose-time-effect relationship. Drug effects are a result of the dose administered and the time from absorption to elimination. Medication dosage, time the medication is absorbed by the body, and the duration of action are all interrelated and interdependent. The duration of a medication’s effect is based on the half-life of the medicine. Elimination half-life (T), also called biological half-life, is the time it takes for 50% of a drug to be cleared from the bloodstream. Each drug has a unique half-life dependent on its characteristics. Certain conditions, such as decreased liver or renal function, will alter the half-life of medications. It is important to note that a medication may go through many of its half-lives before it no longer has a therapeutic effect on the body. This must be recognized when calculating subsequent doses of the same medication to maintain a therapeutic level of its desired effects. Some half-lives are of short duration, such as those used in general anesthesia (a few minutes). Others may have a half-life of several days, such as those used to treat hypothyroidism. Therefore drugs with long half-lives are dosed less frequently than those with short half-lives. Essentially, drugs with short half-lives are said to leave the body quickly—in 4 to 8 hours. Drugs with long half-lives are said to leave the body more slowly—in more than 24 hours, and there is a greater risk for accumulation of these medications in the bloodstream and toxicity. A common example in the surgical setting is the administration of heparin sodium to achieve anticoagulation during vascular surgery. It has a relatively short half-life of approximately 60 to 90 minutes and so would have to be administered frequently to maintain its initial effect.

Other terms related to drug effects are efficacy and potency. Drug efficacy is the degree to which a drug is able to produce its desired effects. Potency is the relative concentration required to produce that effect, as in how much of the drug is needed.

Bioavailability is the extent to which an administered amount of a drug reaches the site of action and is available to produce the drug effects (as described in Chapter 1). This is influenced by drug absorption and distribution to the site of action. Bioavailability is important in pharmacokinetics because it must be taken into consideration when calculating medication doses, especially those administered via nonintravenous routes. For intravenous administration, the bioavailability of the drug is considered to be 100% because it reaches systemic circulation immediately. Factors that affect bioavailability are form of the medication given (tablet, liquid, inhalation, etc.); route of administration (enteral, parenteral, etc.); gastrointestinal (GI) motility; food, herbals, and other drugs given; and liver function. Using heparin sodium as an example, see Table 4-A for a comparison of onset, peak, and duration when given subcutaneously and intravenously.

Advanced Practices: Learning the Language (Key Terms)

Using your textbook or a standard medical dictionary, look up and write the definitions of each term.

• efficacy

• half-life

• potency