Clinical Reasoning and Clinical Judgment

Learning outcomes

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1. Map and describe key elements of critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment.

2. Clarify nurses’ unique role in health care, including their main responsibilities related to diagnosis and management of medical and nursing problems.

3. Address how to use critical thinking indicators and the 4-Circle CT model as tools to promote critical thinking.

4. Address the relationship among patient safety goals, nursing surveillance, nursing process, and critical thinking.

5. Describe outcome-focused, evidence-based care in your own words.

6. Explain the differences among clinical, functional, and quality-of-life outcomes.

7. Discuss the roles of ethics codes, standards, guidelines, and laws in making decisions.

8. Compare and contrast the diagnose and treat and the predict, prevent, manage, promote approaches.

9. Clarify the purpose of each phase of the nursing process.

10. Make decisions about your scope of nursing practice.

11. Apply the “four steps” and “five rights” to delegate effectively.

12. Decide where you stand on the continuum of novice to expert.

13. Address how electronic health records and health information technology affect thinking.

14. Identify at least three things you can begin to do immediately to improve your clinical reasoning and critical thinking skills.

Key concepts

Goals of nursing, outcomes of nursing, novice thinking, expert thinking, competency, evidence-based practice, quality improvement, teamwork, collaboration, patient- and family-centered care, safety, empowerment, patients’ rights and privacy, population-cased care, human responses, health information technology, meaningful use, context, practice scope, qualifications, surveillance, predictive care, delegation, teamwork, collaboration, disease and disability management. See also previous chapters.

Nurses: the glue and conscience of health care

Consider the words of a parent of an acutely ill child:

Compassion is no substitute for competence. In superficial, short-term encounters, a smiling face and a gentle hand impress. In the long term, it’s competence that you value. You find that kindness is a relatively abundant commodity. It’s confidence, borne of knowing, that’s too often in short supply. Does this mean I found myself disinterested in compassion? Not at all. But I also found it didn’t count for much unless it was bundled with competence.1

When you choose to be a nurse, you become part of a profession that’s often called “the glue and conscience” of health care. Nurses are “the glue” because they hold care systems together. In many case, nurses are the only regular, qualified health care providers consistently available. Through their organizations, nurses are the conscience of health care.2

In Gallup poles, health care consumers consistently rank nurses as being the number-one most-trusted professionals.3 Working on the front line in complex settings—hospitals, specialized centers, home care, long-term care, schools, and communities—nurses spend more time with patients than any other professional. They promote health, monitor and manage acute and chronic problems, and teach patients and families to do the same.

Your ability to think critically and develop sound clinical reasoning and judgment affects the lives of many. You need to be prepared for a job that’s much more than a caring presence. You need to know how to manage resources, prevent complications, and promote physical and mental well-being in diverse patients with complex issues.

This chapter helps you gain the knowledge, insight, and skills needed to develop competent clinical reasoning and clinical judgment. Chapter 6 will allow you to practice clinical reasoning skills by having you work with case scenarios that are based on real experiences.

Goals and outcomes of nursing

To better understand nurses’ thinking, let’s consider the question “What are the major goals and outcomes of nursing?”

Goals of Nursing

Nurses aim to achieve the following goals in a safe, efficient, and humanistic way:

1. To prevent illness, injury, disability, and complications (and teach people to do the same).

2. To help people—whether they’re ill, injured, disabled, or well—to have an optimum quality of life (the best possible function, independence, and sense of well-being).

3. To continually improve patient outcomes, care delivery practices, and nurses’ ability to be effective and satisfied in their jobs.

Outcomes of Nursing

Broadly speaking, the following shows the major outcomes that demonstrate the benefits of nursing care.

After receiving individualized, evidence-based care, health care consumers will demonstrate improved physical, mental, and spiritual health, as evidenced by the following:

• Absence of (or reduction in) signs, symptoms, and risk factors of illness, disability, or injury

• Use of behavior strategies and behaviors that evidence shows promote health, function, and quality of life

• Documentation of individualized, evidence-based, state-of-the-art care that focuses on best practices

What Are the Implications?

There are three main implications of the goals and outcomes of nursing:

1. Because the conclusions and decisions we as nurses make affect people’s lives, our thinking must be guided by sound reasoning—precise, disciplined thinking that promotes accurate data collection that’s as complete and in-depth as the situation warrants.

2. Nursing’s ultimate goal is for people to be able to manage their own health care to the best of their ability, so we must stay focused on patient perceptions, needs, desires, and capabilities.

3. Because nursing is committed to achieving high-quality outcomes in a cost-effective, timely way, we must constantly seek to improve both our own ability to give nursing care and the overall quality and efficiency of health care delivery. We must work to find answers to questions like “How can we achieve better outcomes?” “How can we improve satisfaction with our services?” “How can we contain costs, yet maintain high standards?” and “How can we ensure competent nursing practice and retain good nurses?”

Critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment

Let’s review some important points made in the previous chapters:

1. Nurses tend to use the terms critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment interchangeably. Critical thinking is an “umbrella term” that includes clinical reasoning, clinical judgment, and reasoning outside of the clinical setting (e.g., reasoning in your personal life or during classroom or testing experiences).

2. Critical thinking and clinical reasoning are thinking processes; clinical judgment is the result of the thinking (the opinions you form or decisions you make).

3. All critical thinking depends on the accuracy and quality of communication—mutual exchange of information. Communication problems are major causes of mistakes and adverse outcomes such as falls and care omissions.4

4. Critical thinking (and clinical reasoning and clinical judgment) in nursing:

• Is guided by standards, policies, ethics codes, and laws (individual state practice acts and state boards of nursing).

• Is based on principles of nursing process, problem-solving, and the scientific method (requires forming opinions and making decisions based on evidence).

• Focuses on safety and quality, constantly reflecting, re-evaluating, self-correcting, and striving to improve.

• Carefully identifies the key problems, issues, and risks involved, including patients, families, and key stakeholders in decision-making early in the process. (Stakeholders are the people who will be most affected [patients and families] or from whom requirements will be drawn (e.g., caregivers, insurance companies, third-party payers, health care organizations.)

• Applies logic, intuition, and creativity and is grounded in specific knowledge, skills, and experience.

• Is driven by patient, family, and community needs, as well as nurses’ needs to give competent efficient care (e.g., streamlining charting to free nurses for patient care).

• Calls for strategies that make the most of human potential and compensates for problems created by human nature (e.g., finding ways to prevent errors, using technology, and overcoming the powerful influence of personal views).

5. You begin to learn critical thinking skills in school, but you develop them on the job with strong teachers, dialogue, and clinical experience. Using a common reference or tool as a “talking point” to promote ongoing dialogue about what’s going well and what needs to be improved is essential. Standard tests are helpful in testing knowledge—an important part of critical thinking. They also may test some critical thinking skills. Based on a recent study, critical thinking instrument use has not met success in nursing.5

6. Ensuring patient and caregiver safety and welfare must be the top priority in all thinking in nursing. Before you perform nursing actions or give medications, ask yourself, “Do I know why this particular action, treatment, or medication is indicated for this particular patient?”

7. You’re accountable for determining the limits of your own knowledge. You’re also accountable for ensuring that patients, families, and caregivers you supervise have the knowledge they need to proceed with care safely and effectively.

Critical Thinking and Evidence-Based Strategies

Let’s examine the relationship between critical thinking and evidence-based strategies.

If you substitute the word important for critical, critical thinking is “important thinking.” Furthermore, critical thinking is important thinking that evidence suggests must be done at specific points in care to achieve specific outcomes. For example, there’s important thinking that must happen at each point in the nursing process (during Assessment, Diagnosis, Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation). Usually, the “important thinking that must be done” is addressed by using the term “strategies”: What strategies does the evidence suggest we need to think about using in this situation?

Mapping Critical Thinking

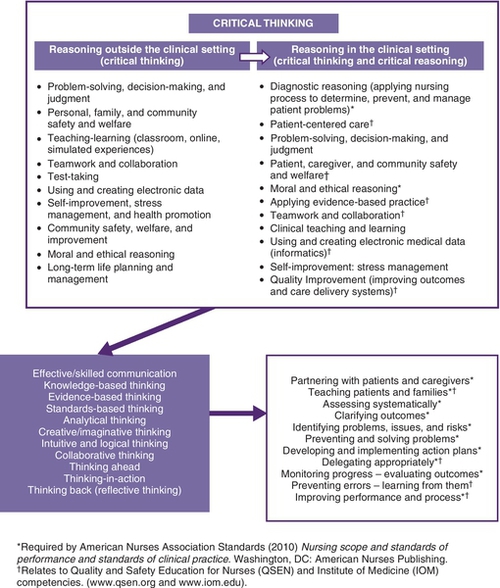

Mapping critical thinking gives you a broad view of what critical thinking in nursing entails. Study Figure 4-1, which maps the relationships among key aspects of critical thinking. Also study Box 4-1, which gives interesting conclusions made by author Christine Tanner after analyzing almost 200 articles.

Improving Practice and Performance

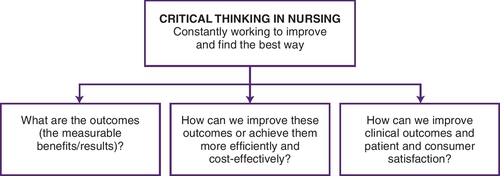

To many nurses, critical thinking simply means good problem-solving. Although problem-solving skills are required, you need a broader view of critical thinking to succeed in today’s competitive health care setting. If you don’t have a sincere desire to improve—to find ways to broaden your knowledge and skills and to make current practices more efficient and effective—you aren’t thinking critically. As you can see in Figure 4-2, critical thinking requires a commitment to look for the best way, based on the most current research and practice findings (e.g., the best way to manage pain in a specific person or for a specific health problem).

Critical thinking indicators and the 4-circle model

Being familiar with critical thinking indicators (CTIs)—short descriptions of behaviors that demonstrate the knowledge, characteristics, and skills that promote critical thinking in the clinical setting—is central to developing critical thinking. If you’re not familiar with CTIs, review pages 9, 45 and 46 which address personal CTIs, knowledge CTIs, and intellectual CTIs. Keep in mind that no one is perfect or able to demonstrate all of the behaviors perfectly all the time. If you use the CTIs as a checklist, you can compare yourself with the listed indicators and decide what you do well and what needs improving. You also can use the CTIs to jog your mind about what you have to do to think critically when you’re in a new or complex situation. For example, when you know that a key intellectual CTI is assessing systematically and comprehensively, it’s likely that one of your first thoughts will be, “I need to figure out a way to assess this patient in a systematic, comprehensive way.”

The 4-Circle CT model (page 15) also helps you assess and improve your ability to think critically. Asking questions like “What parts of the circles do I need to work on most?” helps you prioritize what knowledge and experience you need to gain. Don’t be ashamed of inexperience. You’ll get there. Tell your supervisor, preceptor, or educator when you identify skills you need to work on. It not only helps you, it helps them to prioritize your learning needs and make assignments that help you broaden your skills and keep patients safe.

Novice versus expert thinking

Consider the following scenario.

We’re all novices at one time or another. We all know what it’s like to be new at something and watch an experienced professional and wonder, “Will I ever know this much?” And almost always, with time and commitment, we soon find ourselves helping someone else who looks at us and thinks, “Will I ever know this much?”

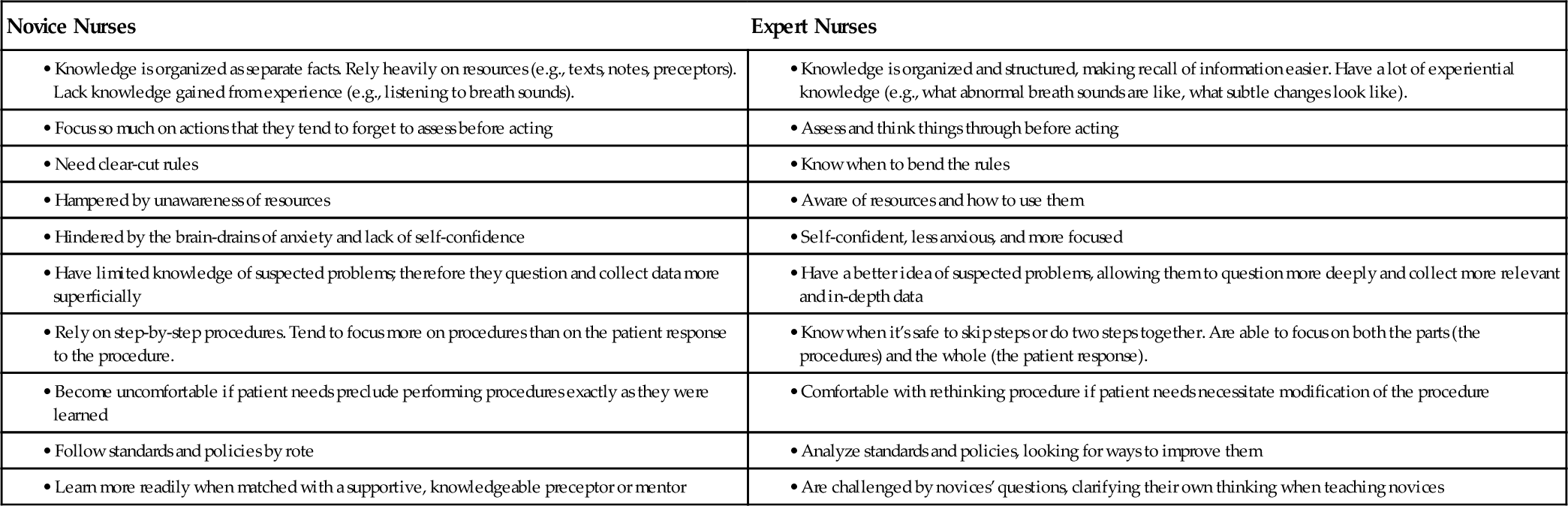

Decide where you stand in relation to novice or expert thinking by studying Box 4-2, which describes the stages novices go through to become experts. Then study Table 4-1, which compares novice and expert thinking. If you’re a novice, determine some things you can do to improve your thinking. If you’re an expert, decide how you can help a novice.

Table 4-1

Novice Versus Expert Thinking

Source: Copyright © 2014. http://www.AlfaroTeachSmart.com

Paying attention to context

A colleague of mine says, “I know my students are thinking critically when I ask them questions and they respond ‘It depends.’” Critical thinking changes depending on context (circumstances). One size doesn’t fit all. What works in one situation may not work in another. For example, think about the difference between working in pediatrics versus working with adults. Growth and development issues and differences in anatomy and physiology affect many aspects of care. Realize that you may be an expert nurse, but if the circumstances change and you’re unfamiliar with giving care under those circumstances, you are more like a novice. Sometimes, you may be familiar with the care but unfamiliar with the patients. Don’t be afraid to say, “I’m unfamiliar with dealing with these circumstances and need help.”

Trends affecting thinking

It seems like health care is changing as quickly as you can say the word computer. Pardon the word play, but computers and health care technology are one of the main reasons for rapid change. From diagnostic technology to information management and decision support, computers are at the core of many changes in health care. This section describes major changes that affect how you think and work today.

Increased Nursing Responsibilities

The roles of licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced practice nurses (APNs) continue to expand. Knowing your qualifications and scope of practice (addressed later in this chapter) is key.

Institute of Medicine Competencies

The 2000s brought a wake-up call for health care consumers and providers. We experienced terrorism, hurricanes, disasters, and new diseases that threatened large populations on unprecedented scales. Institute of Medicine (IOM) studies revealed that because of reliance on outmoded systems, there were many safety and quality problems in health care.6–8 The IOM concluded that poorly designed systems set staff up to fail—regardless of how hard they tried. Four underlying reasons for inadequate care were cited 6–8: (1) Growing complexity of medical science and technology, (2) increased number of people with chronic conditions, (3) poorly organized health care delivery systems, and (4) lack of use of informatics (the use of computers to facilitate the acquisition, storage, retrieval, and use of information). As a result, the IOM developed core competencies stating that all health care providers must be able to provide patient-centered care, work in interdisciplinary teams, employ evidence-based practice, apply quality improvement methods, and use informatics.

Quality and Safety Education for Nurses

Nurse educators responded to the IOM competencies by developing the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project. The QSEN goal is to prepare future nurses to gain the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to continuously improve the quality and safety of the health care system.9 QSEN clarifies what the IOM competencies mean to nursing in the following ways9:

• Patient-centered care: Recognize patients or their designees must be the source of control. Make them full partners in giving compassionate and coordinated care based on respect for their preferences, values, and needs.

• Teamwork and collaboration: Function effectively within nursing and interprofessional teams, fostering open communication, mutual respect, and shared decision-making to achieve high-quality patient care.

• Evidence-based practice (EBP): Integrate best current evidence with clinical expertise and patient/family preferences and values for delivery of optimal health care.

• Quality improvement (QI): Use data to monitor the outcomes of care processes, and use improvement methods to design and test changes to continuously improve the quality and safety of health care systems.

• Safety: Minimize risk for harm to patients and providers through both system effectiveness and individual performance.

If all this sounds familiar to you, it may be because we’ve already addressed many of these issues. Content related to IOM and QSEN competencies is integrated throughout this book. For example, patient-centered care is stressed throughout. EBP and QI are addressed in the next chapter; teamwork and collaboration skills are the focus of Chapter 7.

National Practice Safety Goals Implemented

Recognizing that safety must be top priority, new standards based on national practice safely goals (NPSGs) are implemented in virtually all health care organizations.10 Acknowledging that improvements happen when mistakes are reported—rather than hidden—regulations implementing the 2015 Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act (PSQIA) began in 2009.11 This act establishes a voluntary reporting system to increase the data available to assess and resolve patient safety and quality issues. To encourage the reporting and analysis of medical errors, PSQIA provides federal privilege and confidentiality protections for error reporting and patient safety information (called Patient Safety Work Product).12

Patients’ Rights and Privacy Laws

Patients’ rights and privacy are guaranteed by federal and state laws.13 For example, patients have the right to have copies of their medical records, and to keep them private, as stated in Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy laws. Other rights are upheld by health care standards. For example, patients have the right to have communication and cultural needs met. Most health care organizations have a patients’ bill of rights that addresses specific rights (see Appendix E).

Patient-Centered and Family-Centered Care

Acknowledging that emotional, social, and developmental support are central to allocating resources and achieving outcomes efficiently, organizations work to develop a culture of patient-centered and family-centered care. Patients and families are viewed as key members of the health care team. This approach aims to shape policies, programs, facilities, and staff day-to-day interactions to focus on greater patient and family satisfaction.14

Population-Based Care: Meeting Diverse Needs

We recognize that nurses must meet the needs of diverse patient populations (e.g., patients of certain cultures, age groups, languages, or sexual orientation). The Joint Commission—the main accrediting body for health care organizations—has set standards for population-based care. You can download a road map to meeting these standards entitled Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence and Patient- and Family-Centered Care: A Road Map for Hospitals from http://www.jointcommission.org/Advancing_Effective_Communication/.

Empowering Patients: Nurses as Stewards for Safe Passage

Two important shifts in thinking empower patients and families to manage their own care:

• Move from “I know what’s best for you.” to “I want to empower you to make your own decisions.”

• Change “I’m here to take care of you.” to “I’m here to make sure you know how to take care of yourself when I’m not here.”

Much like a ship’s steward—who has the job of protecting passengers on a journey—your job as a nurse is to protect patients and help them navigate safely through the health care system. As a steward, you hold patients’ lives in your hands, but they should be “at the helm,” directing where they want to go. Box 4-3 (Speak Up initiatives) gives an example of how we encourage patients to stay involved in their care and speak up when they have concerns. You’ll get more strategies in Developing Empowered Partnerships, Skill 7.3, in Chapter 7.

Health Information Technology and Electronic Health Records

Critical thinking and clinical reasoning depend on having ready access to accurate, organized, complete patient information. Federal initiatives push for “meaningful use” of informatics—the use of health information technologies (HIT) to facilitate the acquisition, storage, retrieval, and use of key data by all health care professionals.15 To streamline care delivery and improve outcomes, these initiatives aim to facilitate the flow of shared health information among patients and their care providers.

In most cases today, you use electronic or printed standard tools that influence your thinking. Standard evidence-based tools are essential to collecting complete information, communicating care, improving decision-making, promoting efficiency, preventing mistakes, and keeping everyone “on the same page.” However, we’re still in the early stages of streamlining electronic health records (EHRs), and HIT products are only as good as the designers make them. We have to help “the humans” use them with active, critical minds. As with all complex systems, we’ll continue to experience growing pains. For example, some educators tell me that electronic charting sometimes gets in the way of thinking—the staff seems more involved with what computers tell them than what patients tell them. As another example, each year, the Emergency Care Research Institute puts together a list of the top 10 medical technology hazards to patient safety (http://www.ecri.org).

To improve electronic systems, nurses—now extensions of humans—must be involved in planning, development, and testing them. Be a critical thinker and an active voice in improving systems. If something about your EHR seems error-prone or time-consuming (e.g., having to chart the same data in more than one place), tell your manager, educator, or clinical documentation specialist.

Standard, interdisciplinary tools such as critical pathways (tools that outline care management for particular problems, such as postoperative care of knee surgery) and algorithms (tools that describe a sequence of steps to take under specific circumstances, such as how to proceed when a patient arrives in the emergency department complaining of chest pain) are the norm. You can find up-to-date examples of critical pathways and algorithms on the Internet by searching these terms.

When you use well-designed, evidence-based tools and HIT, two things happen that promote critical thinking: (1) As you use the same tools over and over again in various situations, your brain creates a mental file of what’s most important (e.g., what data must be collected and what to assess first). (2) The documentation associated with the tool gives you and the rest of the team a record you can reflect on to identify patterns and pick up omissions. But remember, tools, HIT, and EHR must be designed for specific purposes—one size doesn’t fit all.

Standard Tools Prevent Miscommunication

To prevent miscommunication among caregivers, safety standards stress the need for standard communication tools. For example, the Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) tool (Box 4-4) is often used for change-of-shift reports (hand-offs) and for reporting problems to physicians.

Time-Outs Promote Group Thinking

In today’s fast-paced clinical setting, many professionals are involved in giving care to one patient—there are many “cooks stirring the pot.” We must ensure that “the right ingredients” go into the “pot” (the patient) at the right time. We need everyone’s eyes, ears, and brains to prevent mistakes. Time-outs, in which the entire team stops to become focused and on the same plan of care are used to prevent errors. There are two kinds of time-outs. One is routine, such as at the beginning of surgeries, when patients’ identities and surgical procedures are double- and triple-checked. The other type of time-out is spontaneous. If at any time any team member—nurse, nursing aid, respiratory therapist (RT), or physician—recognizes an actual or potential risk for harm to the patient, he or she is responsible for calling a time-out and pointing out the concern (the rest of the team is accountable for listening and deciding how to address it).

Health Care Reform

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act brings many changes. Among them are the emergence of accountable care organizations that aim to reduce fragmented care and provide seamless, high-quality, patient-centered care for Medicare beneficiaries. To reduce costs and increase quality and safety, issues like nurse-patient ratios and the advantageous use of APNs are studied. To get up-to-date extensive information on how health care reform affects nursing, enter “health care reform” into the search field of the American Nurses Association (ANA) website (http://www.nursingworld.org).

Box 4-5 summarizes additional trends that affect nurses’ thinking.

Predict, prevent, manage, promote

Care has shifted from a diagnose and treat (DT) approach, which implies that we wait for evidence of problems to start treatment, to a predictive model: predict, prevent, manage, and promote (PPMP).16

PPMP is a proactive approach that aims to predict and manage risk factors before problems arise. PPMP is based on evidence. Thanks to research, we now can predict when people are at risk for certain problems and, if needed, begin an aggressive prevention plan. Sometimes prevention requires treatment (called prophylaxis).

We have evidence-based recommendations for vaccines. For example, with whooping cough (pertussis), to protect the most vulnerable (infants and children), it’s recommended that not only children get vaccinated but also their parents, grandparents, and other caregivers.

More examples of evidence-based recommendations are:

• To prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE), the use of pulsating antiemboli stockings is standard during and after many surgeries. Because VTE has potentially fatal complications, including pulmonary embolism, VTE prevention is a major health care concern.

• For those with significant exposure to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), treatment begins immediately, before there’s evidence of the virus in the blood.

Four Key Strategies

The PPMP approach requires you to do four main things:

1. Predict common problems and complications, and then develop a plan to monitor and prevent them. For example, if you’re caring for someone who has just arrived in the emergency department with a heart problem, you:

• Involve the patient in detecting and preventing complications (e.g., tell him to let you know if he has any new symptoms).

• Begin nursing surveillance (the close observation of patients at risk for complications). Monitor for early signs and symptoms that indicate increasing problems (e.g., irregular pulse, fluid in the lungs, ankle swelling, and chest discomfort).

• Be sure that you’re prepared to manage complications (e.g., have a fully prepared emergency cart nearby, and know how to use it).

2. Focus on risk management. Screen for the presence of risk factors, and identify ways to eliminate or manage them. For example, suppose that you make a home visit to assess an infant. As part of the assessment, you look for risks to the infant’s safety (check where the baby sleeps, and find out if the parents are aware of possible infant hazards). If you identify risks to the baby’s safety, you’re responsible for making a plan to correct the situation. Failing to make a plan may be considered negligence.

3. Use technology to reduce errors and improve accuracy and efficiency. Ask, “What technology can we use to monitor this patient and prevent complications?” For example, for years, to ensure proper placement of central venous lines, we obtained chest x-rays after insertion to be sure the lines were in the vein, not in the chest cavity. Now we know the importance of preventing this complication by using real-time ultrasound as the line is inserted.

4. Encourage behaviors that promote health, optimum function, independence, and sense of well-being. For example, explain to patients with asthma that a walking or exercise program is key to promoting optimum lung function, encourage all smokers to stop, and stress the need for checking with the primary care provider for recommended health screening (e.g., such colonoscopy after age 50).

For more on risk management, health screening, and health promotion: Go to Healthy People 2020 Initiatives (http://www.healthypeople.gov); the Harvard Center For Risk Analysis (http://www.hcra.harvard.edu/); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/); and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org).

The PPMP approach—predict, prevent, manage, promote—prevents complications, saves lives, prioritizes care, improves satisfaction, and contains costs. The following scenario shows the importance of risk management and being proactive when promoting health and managing health problems.

Point of Care Testing Fine-Tunes Care

Another example of applying the proactive PPMP model is point-of-care testing—testing done during the course of nursing care. Point-of-care testing is a key part of managing some health problems. For example, with acute brain injuries, nurses perform highly skilled neurological assessments at least every hour. These assessments help identify subtle changes that are then used to guide how the patient is managed on an hour-by-hour basis. Diabetes management is another example. Nurses manage diabetic regimens in skilled care settings and also teach patients how to manage their diabetes based on their own real-time blood-glucose monitoring.

Rapid Response Teams and Code H (Help)

Rapid response teams (RRT) and Code H (help) are great examples of using the whole team’s brain power to ensure early intervention. The complexity of care today makes it difficult for nurses to balance their patient load. If a nurse is worried that someone’s condition is deteriorating, he or she calls the RRT to do an assessment. The RRT usually is staffed by nurse managers, house physicians, RTs, critical care nurses, and pharmacists. Code H was developed after 18-month-old Josie King died when her family was unable to get her the attention they felt she needed.17 With Code H, patients, families, and visitors can trigger levels of rapid response. For example, patients and visitors can call a code number, which goes directly to hospital operators. The operators are trained to ask questions according to an algorithm. Callers who report something important, such as bleeding or chest pain, are routed immediately to the RRT. If the call is about problems like delays in getting pain medications, lack of communication, or some issue that doesn’t require the RRT, the operator triggers a Code H. In this case, only the nurse manager responds (within minutes of the call). Even if the Code H turns out to be something very mild, families feel reassured to know that they will be heard. Using RRT and Code H saves lives and improves job satisfaction because nurses get help when they need it.

Disease and Disability Management

Disease and disability management—care that focuses on keeping people with chronic diseases and disabilities healthy—is an important part of the PPMP approach. We now manage chronic conditions over time, rather than waiting for episodes of relapse or crisis. For example, with asthma, we don’t just keep treating asthma attacks. We manage the asthma by monitoring individual with asthma when healthy, fine-tuning medications and inhalers to keep them symptom-free. In this way, we ensure that they receive the most current, effective drugs with the least side effects.

We can expect nursing roles related to disease and disability management to grow. Studies find that using team-based, nurse-led care models significantly improves the condition and quality of life of patients with multiple chronic illnesses. Patients receiving this type of care achieve better control of chronic conditions such as depression, heart disease, and diabetes compared with those given standard care in a primary care setting.18

Outcome-focused, evidence-based care

From professional and economic perspectives, the care we give must focus on outcomes and be driven by the best available evidence. We must be able to answer questions like:

• Exactly what does the patient, family, client, or group need to achieve?

• Have the best-qualified professionals decided what, realistically—based on circumstances—can be achieved?

• Have the key stakeholders been included in decision-making?

• What evidence indicates that the outcomes are likely to be achieved in this particular situation?

EBP is discussed in depth in the next chapter. For now, just remember that it’s important to evaluate the strength of the evidence that supports your plan of care. Determining Patient-Centered (Client-Centered) Outcomes, Skill 6.14, in Chapter 6 gives detailed information on how to determine outcomes.

Clinical, Functional, and Other Outcomes

Determining overall care quality requires you to examine outcomes from several perspectives. Study the following types of outcomes listed in the context of how they apply to a surgical repair of a fractured hip. Think about the importance of considering all the outcomes to determine overall care quality.

• Clinical outcomes: To what degree are the patient’s health problems resolved? For example, is the hip healed?

• Functional outcomes: To what degree is the patient able to function independently, physically, cognitively, and socially? For example, is the person able to do required daily activities without help? Are there problems with cognitive function?

• Symptom severity and quality-of-life outcomes: To what degree is the patient free of symptoms and able to do desired, as well as required, activities? For example, is there any hip pain and is the person able to meet physical work requirements and do favorite activities?

• Risk reduction outcomes: To what degree is the patient able to demonstrate ways to reduce health risks? For example, is he able to explain ways of improving safety, such as using a cane when fatigued? Does he keep his home free from hazards that may cause falls?

• Protective factor outcomes: To what degree does the patients’ environment protect them from deteriorating health? For example, when bedridden, are bedrails up as needed and skin care protocols followed?

• Therapeutic alliance outcomes: To what degree does the patient express a positive relationship between himself and health care professionals? For example, when asked, does he state that he feels free to ask questions?

• Satisfaction outcomes: To what degree do the patient and family express satisfaction with care given? For example, when asked, do they state that they had competent, efficient treatment? Were services convenient?

• Use of services outcomes: To what degree were appropriate nursing services used? For example, was a case manager used, if needed?

Dynamic Relationship of Problems and Outcomes

There’s a close, dynamic relationship between problems and outcomes. Sometimes you’ll find yourself focusing on problems and sometimes on outcomes, depending on the situation. Think about the following examples:

• You’re working with a patient on a respirator, and the desired outcome is that the patient has adequate ventilation. You see that the patient seems to be struggling for air. You check the tubing and see a lot of water from condensation. You empty the water. If the patient is still struggling, you continue to look for other problems that might be interfering with adequate ventilation. For example, you assess breath sounds and help the patient to get in a position to cough and clear mucus. You continue looking for problems until you reach your desired outcome.

• You’re working with a group with many complex issues. Instead of getting bogged down in the problems, you say, “It’s going to take us forever if we stay mired in long-standing, complicated issues. Let’s focus on results, rather than problems. Let’s decide together the major things we want to achieve and then get agreement on what we need to do to achieve them.”

As you can see, to engage in critical thinking, you need to focus on both the problems and the outcomes. Together, they serve as a compass that promotes sound reasoning that’s tailored to each unique patient situation.

Critical thinking exercises 4.1

Critical thinking exercises 4.1

Example responses are in Appendix A.

1. Fill in the blanks in a to f by choosing from the following words: responses, actions, decisions, legal, satisfaction, outcomes, nature, potential, strategies, omissions, falls, mutual, result, processes, outside, umbrella, priority, top, welfare, caregiver, patient.

a. Ensuring _______ and ________ safety and ______ must be _______ ______ in all nursing thinking.

b. Critical thinking is an ________ term that includes clinical reasoning, clinical judgment, and reasoning __________ of the clinical setting.

c. Critical thinking and clinical reasoning are thinking ________. Clinical judgment is the ________ of the thinking (the opinions you form or decisions you make).

d. Critical thinking depends on the accuracy and _________ exchange of information. Communication problems are major causes of mistakes and adverse outcomes such as ______ and care _________.

e. Critical thinking calls for ________ that make the most of human ________ and compensate for problems created by human _________ (e.g., finding ways to prevent errors, using technology, and overcoming the powerful influence of personal views).

f. Critical thinking means more than fixing problems—it means fixing them in a way that gets the best _______ from a cost, time, and patient _______ perspective.

2. Study Box 4-3 (page 85), and decide how you would handle a drug addict who insists that he or she must have more medication.

3. How do standards, policies, ethics codes, and laws (individual state practice acts and state boards of nursing) relate to critical thinking?

4. Using your own words and giving examples or drawing a map, explain how you use the PPMP approach to health care delivery.

5. Decide “what’s wrong with the picture” in the following scenario.

Think, pair, share

Think, pair, share

With a partner, in a group, or in a journal entry:

1. Discuss where you stand in relation to novice versus expert thinking (see Table 4-1, page 82, and Box 4-2, page 81).

2. Address the impact of effective communication and cultural competence as described in Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence and Patient- and Family-Centered Care: A Road Map for Hospitals (http://www.jointcommission.org/Advancing_Effective_Communication/).

3. Examine how the core concepts of patient-centered and family-centered care posted at http://www.ipfcc.org/faq.html affect patient outcomes and affect nursing care.

4. Think about people you know who are living with chronic diseases or disabilities. How does the PPMP model apply to keeping them healthy? Share their struggles and successes and the factors that help or hinder their ability to stay as well as possible.

5. Practice using “Read and Repeat Back” rules and the SBAR tool (Box 4-4, page 86) with one another.

6. After reading Reducing Medical Mistakes, Talking with Your Clinician, Getting Medical Tests, Planning for Surgery, Getting a Prescription, and Build Your Question List posted at http://www.ahrq.gov/questionsaretheanswer/, discuss ways to encourage patients to be proactive and involved in their care.

7. Decide where you stand in relation to learning outcomes 1 to 8 at the beginning of this chapter (page 75).

8. Drawing from your experience, discuss your thoughts on the following Critical Moments and Other Perspectives.

Critical moments

Critical moments

Zero Tolerance for Bullying and Disrespect

A key part of having a healthy workplace—the foundation for critical thinking—is having “zero tolerance” for bullying and lateral violence. Lateral violence can be a variety of behaviors—from thoughtless acts to purposeful, intentional acts meant to harm, intimidate, or humiliate others. These types of behaviors create a hostile work environment. In its extreme form, lateral violence is bullying—a conscious, deliberate, hostile act intended to harm, demean, and induce fear. Adopting a zero tolerance helps prevent major issues before they happen.

Other perspectives

Other perspectives

Your Most Important Tool

Improving thinking helps you develop the most important tool you have in your toolbox: yourself. This means being clear about who you are as a person, and how your attitudes, assumptions, frames of reference, and tendencies to stereotype affect problem-solving—how your personal choices and behaviors affect communication and interpersonal relationships. You also need very specific ways of looking at what CT [critical thinking] is in context of each particular clinical setting. Too many leaders have the “amorphous blob” concept of CT and just wish people would think better. Then they decree that it’s up to the managers and educators to fix the nurses!!

—Ruth Hansten, RN, PhD, FACHE (personal communication)

Nursing process: the heart of clinical reasoning

As evidence-based approaches continue to evolve, you can expect that the nursing process won’t be the only tool you will learn to promote critical thinking. Learning several models improves your ability to think critically for two reasons: (1) Each model brings new insights, and (2) some models work better in one context than another.

Although you may use more than one model to promote clinical reasoning, the nursing process is the first tool you need to learn, for the following reasons19:

1. American Nurses Association and virtually all specialty organization standards stress that the nursing process—assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate—guides nursing care.

2. The nursing process is a building block for other models and safe practice.

3. Health care documentation systems are based on the “assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate” approach.

4. The nursing process framework is “in synch” with the clinical reasoning models that other health care professionals use: We can talk about problem-solving and prevention in a common way.

5. The NCLEX®, testing services, and clinical certification exams are based on nursing process.

Chapter 6, Practicing Clinical Reasoning Skills: Applying the Nursing Process, gives opportunities to practice applying nursing process. For now, review Box 4-6, which summarizes the purpose and process of each nursing process step. Keep in mind that it’s important to remember the purpose of each phase and that the phases are interrelated. What happens in one phase affects the others.

Proactive, Dynamic, and Outcome-Focused

Today we stress that the nursing process must be proactive and focused on outcomes, risk management, and health promotion—as well as dealing with problems. In the clinical setting, the nursing process is dynamic, unlike how it’s described in books or classrooms. If you jump around in books or classrooms trying to explain how things happen in real life, you confuse people—you have to present content in a logical, step-by-step way. In real life, the nursing process is fluid and changing. You apply principles of nursing process, but move back and forth within various phases, as in the following scenario.

Collecting Versus Analyzing Data

Realize that collecting and recording information isn’t the same as analyzing it. After you record the data, you have to do a lot of analysis to clarify priority problems and risks. Patients rarely have just one problem. They usually have several problems that contribute to one another, requiring you to decide which problems must be dealt with first.

Recognizing the need to analyze and reflect on patient information is especially important with the use of computers to store date. Don’t just dump information into the computer. Find a way to analyze and reflect on it.

Interplay of Intuition and Logic

Let’s examine the question: What roles do intuition (knowing without evidence) and logic (rational thinking based on evidence) play in clinical judgment?

Most agree that intuition—an important part of thinking—is often seen in experts, as a result of years of experience and in-depth knowledge of patients. However, there’s a concern that encouraging the use of intuition sends the message that it’s okay to act on gut feelings without evidence, which is risky. To clarify the use of intuition and logic in clinical judgment, it’s important to answer two questions:

1. Is the rapid thinking that goes on in experts’ heads simply the use of intuition—what many describe as “knowing in your gut”?

2. If you can’t explain your thinking, does it mean that you’re thinking intuitively?

To the outsider, many experts’ actions seem to be based on intuition alone. But, rapid thinking is usually the result of “thinking in pictures”—like watching a video—and using intuition and logic together. There’s a dynamic interplay between intuition and logic. Experts make leaps in thinking with intuitive hunches, then almost at the same time draw on logic and past experience to make well-reasoned conclusions.

Experts who juggle several priorities at once often have trouble explaining their thinking at the very moment it’s happening. But, if it’s really important—for example, if decisions are later challenged in court—they can readily reconstruct the logic of their thinking (and if they can’t, they’re in trouble).

Clinical reasoning requires using your whole brain—both the intuitive-right and logical-left sides. Use intuitive hunches as guides to search for evidence. Use logic to formulate and double-check your thinking, ensuring that your conclusions are based on the best available facts. In important situations, be careful about acting on intuition alone. Ask questions like “Does this make logical sense?” “How do I know I’m right?” “Could this situation actually be counterintuitive?” and “What could go wrong if I act on intuition alone?”

Thinking Things Through

In today’s fast-paced world, we must remember the importance of thinking things through and not jumping to conclusions. In fact, this has become such a problem that there’s a phrase to describe it: “Ready, fire, aim” (instead of “ready, aim, fire”). This phrase refers to what happens with poor assessment and planning. Critical thinking means not jumping to conclusions or acting on impulse. Time constraints today sometimes push you to make diagnoses before you have all the data. Because of the risks of jumping to conclusions and influencing others to do the same, if you aren’t sure of the diagnoses or problems, be prudent and say something like “there seems to be issues with (whatever), but there’s not enough information to completely understand what’s going on.” Issues are problems that are still muddy and not clearly defined.

In Evaluating and Correcting Thinking (Self-Regulating), Skill 6.16, in Chapter 6, there’s a summary of questions to apply the nursing process to determine whether the depth and breadth of your thinking are sufficient.

What About Creativity and Innovation?

Einstein said, “Problems cannot be solved by the same level of thinking that created them.” Creativity and innovation play key roles in critical thinking, and we all need to learn how to promote them, in both schools and the workplace. We need to know how to transform creativity (a new idea) into innovation (a useful approach that evidence shows improves results).20

To keep patients safe, use principle-centered creativity. When you have a creative idea, determine what principles support or negate it. For example, one nurse tried to warm blood before administering it by putting it in the microwave. This is dangerous creativity. Identifying the principles of what happens to protein in the microwave would have stopped this. Figure 4-3 shows an example of principle-centered creativity.

To save time and avoid “reinventing the wheel,” ask questions like, “Is this idea (or way) really better or is it just different?” “What does the research say about this idea? Is this idea useful to end users?”

Don’t be happy with the status quo. Think outside the box. Ask questions like “Are there new evidence-based approaches we should be using?” “Is there something creative we can do?” “How can technology help?” “Who might be willing to give their time?” and “How can we involve patients and families to get better results?”

Is the Care Plan Dead?

As we continue to use standard plans and EHRs, some nurses wonder, “Is the care plan dead?” The answer is that the care plan is alive and well—it’s just changed. Standards mandate that patients have an individualized recorded plan of care that demonstrates that specific needs and problems are being addressed.

You may not find the care plan all in one place. Rather, parts of the plan may be addressed in different places of the health record (e.g., the nursing assessment may be in one place, routine interventions may be covered in critical paths, an individual plan covered in another, and so on).

Why Learn Care Planning When We Use Computers?

Just as using a calculator doesn’t replace having mathematical and problem-solving principles “in your head,” using HIT and EHR doesn’t replace the need to have basic principles of nursing process and care planning in your head. You need a deep understanding of these principles to apply them to your daily work at the bedside, to discuss patient care with others, and to determine whether the plan of care is sufficiently documented. The memory-jog EASE can help you remember the major care plan components.

Expanded roles: greater accountability

Nurses now have greater accountability for various aspects of diagnosis and care management. We have moved from “nurses diagnose and treat only nursing diagnoses” to “nurses diagnose and manage various issues and problems, depending on their knowledge, expertise, and qualifications.” For example, APNs diagnose or manage problems that used to be managed only by physicians (e.g., stable hypertension and common infections).

As nursing responsibilities for all aspects of care grow, you need to have a strong sense of what nurses do in relation to managing medical and nursing problems. Think about the following quotes:

Your doctor’s job is to diagnose your medical problem and prescribe the necessary treatment. My job, as your nurse, is to monitor your body’s response to treatment, help prevent complications before they begin, keep you comfortable, and help you be as independent as possible.21

—Phyllis G. Cooper, MN, RN

The public needs to know that nurses—regular, ordinary bedside nurses, not just nurse practitioners or advanced practice nurses—are constantly participating in the act of medical diagnosis, prescription, and treatment and thus make a real difference in medical outcomes. Nurses can help the public understand that nursing is a package of medical, technical, caring, nursing know-how—that nurses save lives, prevent suffering, and save money. If nurses wear not only their hearts, but also their brains on their sleeves, perhaps the public… will finally understand what nurses know and do.22

—Journalist Susan Gordon

The following ICU blog also gives insight into the complexity of nursing today.

Last night I took care of a man who was hypoxic and needed oxygen via mask. Most people tolerate masks fine, but there are a few that just can’t handle having something on their face. He was one of those few. Even though the nasal prongs were doing the trick, the pulmonologist wanted us to use a mask because “he will probably take a turn for the worse eventually.” (Side rant: This is the same pulmonologist who, upon walking onto the unit, said, “Geena, when you have a critically ill patient, wouldn’t it be at the forefront of your mind to have the chart available?” I replied, “Dr. B, the very fact that I have a critically ill patient who is hypoxemic and trying to climb out of bed actually explains why I don’t have the faintest idea where the chart is.”) Anyway, owing to other circumstances, I didn’t immediately connect that the patient became severely agitated when we applied the oxygen mask. I had to give him an antipsychotic shot and spent as much time as I could at his bedside to avoid having to restrain his arms (which I correctly assumed would make him worse and wouldn’t work anyway… when another nurse watching him for me went ahead and restrained him, he just bent over and put his face to his hand to take the mask off). I tried to chat with him about other things to help take his mind off the bothersome mask, and he finally stopped struggling against the restraints and lay back on the pillow. After a few moments, he looked at me and asked, “How long have you been working here?”

“Three years,” I replied.“Before that, did you get your bachelor’s, or your master’s… ?” Before I could answer him, he finished, “IN TORTURE???”

I’m sure it’s not good nursing etiquette, but I laughed quite hard at that—which made him laugh. I eventually decided that the amount of energy he was exerting to remove the mask far outweighed the benefits of it, so I switched him to the nasal prongs again. After a few minutes of low oxygen saturation (O2 sats) readings, he calmed down considerably and actually drifted off to sleep. His O2 sats came up perfectly, and the rest of the night was fabulous.*

Unique nursing role

As a nurse, you deal with many aspects of managing health problems. However, there’s one thing that’s considered to be nurses’ unique role: Identifying and managing issues to related human responses (how health problems influence each person’s sense of well-being and ability to function independently as a bio-psychosocial human being).23 For example, suppose that you’re caring for Mrs. Hernandez, who has the medical problem of congestive heart failure. Her response to the heart problem is activity intolerance. As a nurse, you’re accountable for monitoring and managing the nursing problem of activity intolerance. But you must assess the status of the cardiac problem before dealing with the activity intolerance. If her vital signs are unstable, you’re accountable for notifying the physician or APN before dealing with the activity intolerance. As you can see, there’s a close relationship between medical problems and human responses. Your role is to focus on both the problems and the human responses.

Boxes 4-7, 4-8, and 4-9 show common nursing problems and potential complications of medical problems and treatment.

Nursing surveillance: monitoring closely

Another key nursing role is nursing surveillance—closely monitoring patients to detect signs and symptoms that may indicate the onset of complications. Unless you’re an APN, you’re not qualified to diagnose and treat medical diagnoses independently. But, you are accountable for the following aspects of care:

• Detecting and reporting signs and symptoms that may suggest a medical diagnosis or complication (e.g., notify the physician if a patient has fever, productive cough, fatigue, and malaise—all symptoms of pneumonia).

• Managing treatment according to standards and plans of care (e.g., with pneumonia, monitor lung sounds, oxygen administration, IV management, and vital signs).

• Preventing complications by recognizing patients at risk, monitoring closely, and implementing preventive actions (e.g., elderly postoperative patients are at risk for pneumonia—a key priority is to monitor respiratory and hydration status and help them cough and breathe deeply).

• Managing human responses to health problems (e.g., humans often respond to having pneumonia by experiencing fatigue, lack of appetite, dehydration, and difficulty clearing mucus).

• Managing problems with independence (e.g., if the person with pneumonia lives alone, he or she is likely to need assistance with shopping and preparing meals).

• Managing emotional and physical discomfort, through both prescribed and holistic strategies (e.g., managing pain medications, using therapeutic communication, and repositioning patients).

• Promoting optimum health, sense of well-being, and quality of life: Nurses promote health by teaching about healthy behaviors.

• Monitoring treatment and medication regimens for adverse reactions, as well as individualizing the regimens within prescribed parameters. Nurses are very involved in ensuring that overall regimens are as safe, effective, cost-effective, and convenient as possible, considering the age, culture, religion, roles, occupation, and lifestyles of those involved. For example, with pneumonia, ask whether prescribed antibiotics are the best available, considering cost, convenience, and results.

Activating the Chain of Command

When a patient’s status indicates the need for more qualified help, you are responsible for activating the chain of command. Activating the chain of command means following communication policies and staying with the problem until the appropriate qualified professional has responded. Think about the following example: You give medication for incision pain, but the patient has no relief. You try repositioning and other holistic measures, but the person still has no relief. You leave two messages for the doctor to call you about this problem. One hour later, you haven’t heard from the doctor, and the patient is still in distress. You are accountable for activating the chain of command and notifying your supervisor about this problem and finding out what to do next.

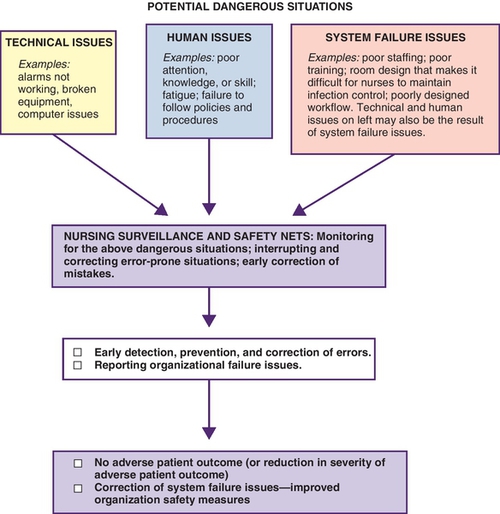

Monitoring for Dangerous Situations

While preventing errors is addressed in detail in Preventing and Dealing with Mistakes Constructively, Skill 7.8, Chapter 7, this section addresses the need to monitor for dangerous situations as part of nursing surveillance. Front-line nurses play an important part in identifying, interrupting, and correcting mistakes. Think about the following strategies that research shows nurses use to prevent and correct mistakes.

Strategies to Identify, Interrupt, and Correct Errors

The following strategies will help you identify and manage errors:24

• Error identification strategies: Knowing the patient, knowing the “players,” knowing the plan of care, surveillance, knowing policy/procedure, double-checking, using systematic processes, and questioning.

• Error interruption strategies: Offering help, clarifying, and verbally interrupting

• Error correction strategies: Persevering, being physically present, reviewing or confirming the plan of care, offering options, referencing standards or experts, and involving another nurse or physician.

Figure 4-4 shows how nursing surveillance for dangerous situations and safety nets promote early intervention and keep patients safe.

Failure to Rescue

Let’s finish this section on surveillance by addressing an issue identified by researchers Clarke and Aiken at the University of Pennsylvania: Failure to Rescue.25,26 Failure to Rescue is a clinician’s inability to save a hospitalized patient’s life when he or she experiences a complication (a condition not present on admission).26 This research, and subsequent work by others, has significantly improved our ability to identify and correct issues related to nursing surveillance.

Next is a summary of what you must know about common problems and complications to be proactive and provide competent nursing surveillance.

Developing clinical judgment

Developing clinical judgment is one of the most important and challenging aspects of becoming a nurse. It’s important because people’s lives depend on it. It’s challenging because thinking in the clinical setting is often fraught with more anxiety and risks than other situations.

Clinical judgment entails things like knowing how to recognize when a patient’s status is changing and what to do about it. For beginners, this is particularly hard because it requires you to recall facts, put them together into a meaningful whole, and apply the information to a clinical situation that may be fluid and changing. For example, you note that someone is pale and sweaty and has a rapid pulse. To use good clinical judgment, you must be able to recall that these are symptoms of shock and that an immediate priority is to take a complete set of vital signs to further evaluate the patient’s condition.

Legal Implications of Diagnosis

As nursing responsibilities grow, it’s important to realize that the terms diagnose and diagnosis have legal implications. They imply that there’s a specific problem that requires management by a qualified professional. If you make a diagnosis, it means that you accept accountability for accurately naming and managing it. If you treat a problem or allow a problem to persist without ensuring that the definitive diagnosis—the most specific, correct diagnosis—has been made, you may cause harm and be accused of negligence. For example, if you deal with chronic constipation without determining whether it has had adequate medical evaluation, you may be missing a major symptom of colon or ovarian cancer (constipation).

Practice Scope and Clinical Decision-Making

With nursing roles changing, how do you know when you are the one who is allowed—who is accountable—for diagnosing and managing specific problems? How do you determine your scope of practice? This question is especially difficult for beginners.

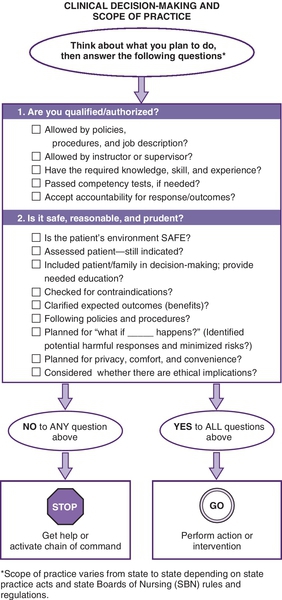

Scope of nursing practice varies from state to state and one setting to another, depending on (1) laws outlined in your state nursing practice act; (2) rules and regulations defined by your state board of nursing (SBN), which is in charge of enforcing the state laws and specifying what nurses may and may not do; and (3) professional standards, policies, procedures, competencies, and job descriptions. Figure 4-5 shows the questions you need to answer to make decisions about your scope of nursing practice.

Decision-Making and Standards and Guideline

Critical thinking and clinical reasoning are is guided by professional standards. Think about the following descriptions of standards.27

• Authoritative statements by which the nursing profession describes the responsibilities for which its practitioners are accountable.

• Reflect the values and priorities of the profession, and provide direction for professional nursing practice and a framework for the evaluation of this practice.

• Define the nursing profession’s accountability to the public and the outcomes for which registered nurses are responsible.

National practice standards give broad standards that address how nurses are expected to plan and give care. ANA practice standards—which delineate use of the nursing process to plan and give care—apply to all nursing care. Each specialty organization (e.g., American Association of Critical Care Nurses, Association of Rehabilitation Nurses) develops its own unique standards. The Joint Commission sets many standards for health care organizations. These standards are often tailored to each organization. Each health care organization usually develops standards to guide decision-making in specific situations (e.g., standards of care, policies, protocols, procedures, care plans, critical paths).

When determining care management, there are three main questions to answer related to standards:

1. Has this facility developed specific standards, guidelines, or policies for the care of this specific situation? For example, if you’re caring for someone with a mastectomy, ask, “Has this facility developed guidelines or pathways for someone undergoing a mastectomy?”

2. Are there national or local EBP guidelines relating to this particular problem?

3. To what degree do these standards and guidelines apply to my patient’s particular situation?

While practice standards and guidelines are key tools that help you make care decisions, you don’t follow them blindly. Decide whether they are appropriate by carefully comparing your patient’s situation with the information in the guidelines. For example, suppose that you’re looking after an elderly man after prostate surgery, and the critical path for this problem states that on the first postoperative day, the patient gets out of bed twice. On the first postoperative day, you assess the man and find he has chest pain. This finding is significant enough for you to question whether he should indeed get out of bed. Could this man be suffering a complication such as myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolus? In this case, it’s your responsibility to report the symptoms and keep the man in bed until a physician or more qualified nurse evaluates him.

Delegating Safely and Effectively

With so much to do and so few to do it, delegating safely and effectively is a crucial nursing skill. Delegation—authorizing someone to perform a selected task in a selected situation, while retaining accountability for results—is an important part of managing time and resources.27,28 It’s also important for passing the NCLEX® exam because it tests knowledge of delegation principles. When you delegate tasks, you’re accountable for decisions made, actions taken, and patient responses during the course of that delegation.

Delegating effectively—a skill that’s developed over time with experience—takes significant critical thinking and judgment. It requires you to understand both patients’ needs and workers’ needs and capabilities.

The following section summarizes when it’s safe to delegate, the four steps of delegation, and the five “rights” of delegation.29,30

Ten strategies for developing clinical judgment

Developing clinical judgment comes with clinical experience. It requires a commitment to study common health problems, seek out clinical experiences, and come prepared to the clinical setting. The following strategies help you plan ahead and make the most of clinical learning opportunities.

1. Keep references—texts, handheld devices, pocket guides, and personal “cheat sheets”—handy, and be sure that you:

• Learn terminology and concepts. If you encounter words like embolus, thrombus, or phlebitis and you don’t know what they mean, look them up as you encounter them, so that they become part of your long-term memory. Learning terms in context helps your brain to store information in related groups, rather than as isolated facts.

• Become familiar with normal findings (e.g., normal lab values, assessment findings, disease progression, growth and development) before being concerned with abnormal findings. Once you know what’s normal, you’ll readily recognize when you encounter information that’s outside the norm (abnormal).

• Ask why? Find out why normal and abnormal findings occur (e.g., “Why is there edema in heart failure, yet none when the heart is functioning normally?”).

• Learn problem-specific facts. You need to know how problems usually present themselves (their signs and symptoms), what usually causes them, and how they’re managed. The following box gives questions you need to answer to be prepared for going to the clinical setting.

2. Apply principles of the nursing process. For example, assess before acting, anticipate, and change approaches as needed. Make judgments based on evidence rather than guesswork.

• Because assessment tools vary from organization to organization, ask your preceptor, teacher, or manager whether there are printed or electronic standard tools to guide thinking and documentation in various situations. Be sure to ask for comprehensive assessment tools and focused assessment tools. Comprehensive tools are usually used for patient admissions. Focus assessment tools are usually used to monitor specific problems.

• Be sure you understand the reasoning behind the tools you use. Finding out why you collect each piece of data on the tool helps you learn what’s relevant to each situation.

• Don’t just record the data. Reflect on what you recorded, looking for patterns and omissions.

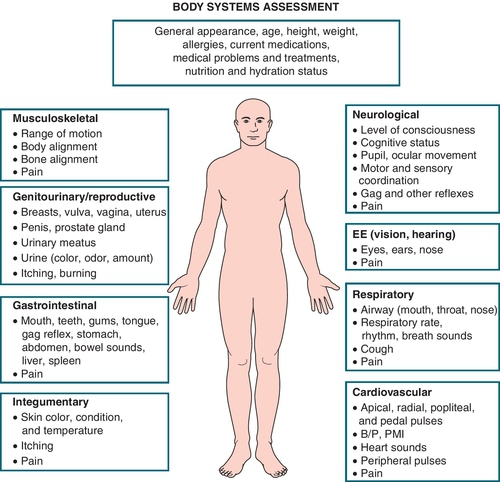

• Realize that the tool you use affects how you think about the data. For example, Box 4-10 shows Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns, a framework that’s often used to organize data to identify problems with human functioning. Figure 4-6 shows the Body Systems approach to collecting data, which helps identify medical problems. Realize that using both ways of organizing data—Functional Health Patterns and Body Systems—helps you to identify nursing problems (e.g., human responses or problems with independence and well-being) and signs and symptoms of medical issues that should be reported to the primary care provider.

3. Learn to think ahead, think-in-action, and think back (reflect on your thinking).

4. Follow policies, procedures, and standards of care carefully, with a good understanding of the reasons behind them. Policies, procedures, and standards of care are designed to help you use good judgment, but you must know the reasons behind them to know when and how they apply.

5. Determine a system that helps you make decisions about what must be done now and what can wait until later (see Setting Priorities, Skill 6.13, in Chapter 6).

6. Never perform actions if you don’t know why they’re indicated, why they work (the rationale), and what the risks for harm are in the context of the current patient situation.

7. When in doubt, activate the chain of command—get help from a qualified professional. Your patients’ right to timely care takes precedence over your need to learn independently. Other professionals can help you decide whether you have time to look up your concerns in a reference. Also learn from your peers’ experiences. Collaborating with classmates is a win-win situation: Asking questions like “What did you look for in that patient?” “How did you know?” and “What was the biggest thing you learned?” helps your classmates clarify their knowledge and helps you learn from being involved in real situations. However, don’t use names or talk about patients in public places where others might overhear (e.g., cafeteria, elevators)—you may be violating HIPAA privacy laws.

8. Seek out simulated, observational, and real experiences. Become familiar with the technology you’ll use (e.g., IV pumps, computers, heart monitors) and the types of problems you’ll encounter before you go to the clinical setting.

9. Remember the importance of caring. Patients describe caring as vigilance (attentiveness, highly skilled practice, basic care, nurturing, and going the extra mile); mutuality (building relationships among nurses, patients, and families); and healing (lifesaving behaviors and freeing the patient from anxiety and concerns).

10. When planning time for nursing care, consider the time required for (a) direct care interventions (things you do directly for or with the patient, such as helping someone walk), and (b) indirect care interventions (things you do away from the patient, such as consulting with the pharmacist or analyzing lab study results).

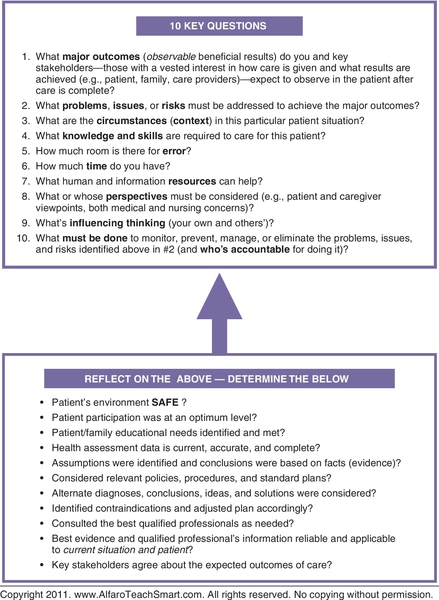

Figure 4-7 shows the relationship of 10 key questions and the reflection you need to do to develop sound clinical judgment.

Charting that shows critical thinking

Let’s end this chapter with a few words of caution: Whether you use paper or electronic charting, be sure your charting shows critical thinking. Your charting is used by others to make patient care decisions. It also reflects whether you’re a critical thinker. If your supervisor or instructor reads your charts and sees nothing but rote repetition of what the person ahead of you charted, a flag goes up that says, “This person never seems to have an original thought.” Follow policies and procedures for charting carefully, because they are designed to communicate important aspects of care, keep patients safe, and meet legal and third-party payer requirements. You may use a system of flowcharts and check marks, but always ask yourself whether there is something different today that you should add.

Make sure your charting reflects use of the nursing process and a strong focus on the following:

1. Assessment: What you assessed in the patient

2. Conclusion: What you concluded about your patient—state the facts to support your conclusions

3. Interventions and Evaluation: What you did, and how the patient responded (remember: assess, intervene, reassess)

4. Safety Measures: Anything you did to correct or prevent adverse responses

Example: Rates incision pain at 7. Dressing clean and dry. Vital signs normal. Appears stable. Pain med given. Bedrails raised. Call bell given and told to call for help if needed. Reassessed 30 min later and rates pain at 2.

Critical thinking exercises 4.2

Critical thinking exercises 4.2

Example responses are in Appendix A.

1. Fill in the blanks in a to h by choosing from the following words: actions, decisions, outcomes, qualifications, accountability, head, nursing, innovation, incomplete, same, knowledge, experience, reflecting, records, legal.

a. Analyzing and ____________ on your patient assessment and related health ______ is key to clinical reasoning.

b. Intuition is often seen in experts, as a result of years of _________ and in-depth ________ of patients.

c. _________ or inaccurate data may cause you to jump to conclusions and influence others to do the _________.

d. Principle-centered creativity and ________ play key roles in critical thinking.

e. Using electronic charting and decision-support systems doesn’t replace the need to have ________ process and care planning principles in your _______.

f. Depending on knowledge, expertise, and _________, nurses have increased _________ for diagnosing and managing various problems.

g. The terms diagnose and diagnosis have ________ implications.

h. When you delegate tasks, you’re accountable for ________ made, ________ taken, and patient _________ during the course of that delegation.

2. Considering the differences in novice and expert thinking, respond to a, b, and c:

a. Compare how your brain thinks when encountering familiar situations with what happens when you encounter unfamiliar situations. For example, think of the difference between what you see and understand the minute you walk into your own home, compared to what it’s like when you are a first-time visitor in someone’s home.

b. Think about the following analogy. When you go to a new clinical setting or have a patient for the first time, it’s like watching a movie for the first time. Each time you see the same movie over and over, you understand it better and see new things. The same thing happens when you are familiar with patients, staff, and routines in a particular clinical setting.

c. What are some things you can do to increase your ability to function in unfamiliar situations?

3. Using the clinical decision-making guide (Figure 4-5, page 107), decide whether you’re allowed to irrigate a nasogastric tube in the clinical setting where you are currently working.

4. An important part of developing clinical judgment is being willing to focus on wants and needs of patients and families. How would you interpret the statements made by the following off-going nurse?

On-coming nurse: “How is the family doing?”

Off-going nurse: “They seem to be fine. They don’t say much, but they’re sticking to visiting hours and have been here 15 minutes this morning and 15 minutes this afternoon.”

5. How do you use the memory jogs MMA and EASE?

6. Imagine that you have a postoperative patient whose blood pressure is alarmingly high. You call the doctor twice, but there is no response. How will you know what to do to activate the chain of command?

7. Suppose your neighbor asks you whether it’s okay to give aspirin to her normally healthy 5-year-old who is alert, but woke up with a fever of 100° F, orally. What would you do?

Think, pair, share

Think, pair, share

With a partner, in a group, or in a journal entry:

1. Discuss the following in relation to the ICU blog (page 99).

a. Risks of applying restraints

b. Independent thinking on the part of the nurse

c. The value of the human relationship between the nurse and the patient

d. The many things that influence hypoxia

2. Take the stress scale test at http://www.teachhealth.com. Identify the stressful things in your life. How are you handling them? What healthy behaviors might help?

3. Discuss the emerging lessons on medication reconciliation posted at http://healthit.ahrq.gov/ahrq-funded-projects/emerging-lessons/medication-reconciliation.

4. Check to be sure you’re familiar with your state practice act, which delineates what actions you can have the legal authority to perform: Read Protect Yourself: Know your state practice act at http://ce.nurse.com (search CE548).