Conservation Medicine to One Health

The Role of Zoologic Veterinarians

Sharon L. Deem

One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.

—Aldo Leopold

The approaches of conservation medicine and One Health are well known to zoologic veterinarians, and, indeed, almost everything we do professionally fits within the objectives of these approaches. However, it is possible that few zoologic veterinarians give sincere thought to the underlying global changes that threaten the conservation of biodiversity and human health and the historical context behind these transformative approaches. In this chapter, both conservation medicine and One Health will be reviewed following a brief overview of current conservation and health challenges, which were the catalyst behind the establishment of both these initiatives. Lastly, the leadership roles of accredited zoos in ex situ and in situ conservation programs and more specifically the role that zoologic veterinarians play within conservation medicine and One Health will be discussed with examples of zoo-led, zoo-supported, and zoo-based projects.

Challenges to the Conservation of Biodiversity and Human Health

Global challenges that threaten the conservation of biodiversity and the health of Homo sapiens are extensive and beyond the scope of this chapter. Briefly, these challenges range from the uncertain, but very real, impacts on species' health exerted by global climate change to the documented increasing interactions among wildlife, domestic animals, and humans, which have resulted in the current concerns regarding emerging infectious diseases (EIDs).

The pressures limiting the long-term survival of many of the wildlife species that zoos are dedicated to conserving are largely human driven (anthropogenic). These pressures include climate change, habitat degradation and fragmentation, introduction of invasive species, trade in wildlife, and exposure to emerging pathogens, all of which are associated with the human population growth, which surpassed 7 billion individuals in 2012. In fact, these anthropogenic changes have led many to contend that planet Earth is presently in a new “Anthropocene” epoch.5 Simply stated, humans are the drivers of planetary health. According to recent scientific reports, humans have transformed between one third and one half of the land surface and now appropriate over 40% of the net primary terrestrial productivity, consume 35% of the productivity of the oceanic shelf, and use 60% of the freshwater run-off each year.29,32,36,40 What might these statistics indicate in terms of resource availability and health challenges for the other species that share the planet with humans? Additionally, with the estimated 50% increase in human consumption of animal-based protein by the year 2020, it is inevitable that human use of resources will continue to rise.12 Lastly, the estimated billions of live wildlife animals and animal products that are traded annually also place heavy burdens that threaten the long-term survival of species.37 In addition to the direct impacts that wildlife trade places on the conservation of species, are the less apparent, but potentially devastating, impacts associated with cross-species microbial mixing and exposure to novel microbes that further threaten the health of all species, including humans.

Concurrent with the recognition of the new Anthropocene era comes the demonstration by recent analyses that species' extinctions occur at rates of 100 to 1000 times the baseline levels in the pre-agricultural era, with these rates increasing steadily.31 For example, it is estimated that since 1970, global population sizes of wildlife species have decreased by 30%.41 With regard to species decline by animal taxa, the species threatened with extinction include 12% of birds, 21% of mammals, 30% of amphibians, and 27% of reef-building corals.23 Zoologic veterinarians must be cognizant of the current conservation challenges and incorporate this knowledge into health programs directed at the conservation of wildlife species, both ex situ and in situ, while ensuring human public health.

Health Care for Species Living in a World of Wounds

During the last few decades, an increasing focus has been placed on conservation and health approaches, termed conservation medicine and One Health. These approaches provide the framework for developing the environmental and health solutions necessary to address the above challenges. The shift to embrace more holistic approaches in ecologic studies, conservation projects, and human public health has led to a number of publications that provide definitions and examples of both these approaches.15,17

Although often presented as new approaches, these initiatives are built on centuries of collaborative thought guided by principles similar to those that direct much of our conservation medicine and One Health work today. This may have been most eloquently phrased as early as the 1800s by the physician Rudolf Virchow in his statement: “Between animal and human medicine, there is no dividing line—nor should there be.” In the 1900s, the term One Medicine was coined and signaled the beginnings of the conservation medicine and One Health initiatives.38 Early leaders of the movement paved the way for the current development of the well-accepted and increasingly practiced approaches of conservation medicine and One Health.

Conservation medicine as an ecologically driven and conservation-minded approach first appeared in the literature in the 1990s.19 Although a number of definitions for conservation medicine exist, at the core is the realization that the health of environments and the animals and the humans within them are intimately related and that multiple disciplines are required to better understand and manage conservation efforts and disease challenges, which impact all three. Conservation medicine may best be defined as a transdisciplinary approach to study the relationships among the health states of humans, animals, and ecosystems to ensure the conservation of all, including Homo sapiens.1,10,19

Starting in the 2000s, the One Health initiative has become widely accepted and increasingly driven by the human medical field, although veterinary medicine has embraced this approach as well. As the One Health approach gains momentum, it may be important to consider how it differs from conservation medicine. One Health may be based less on understanding the ecosystems compared with conservation medicine. In fact, an early definition of the One Health concept stated that this initiative aims to merge animal and human health sciences to benefit both.13 However, as with conservation medicine, a number of recent definitions of One Health do consider ecosystems as important as human and animal health. One unifying theme has been that One Health is a strategy that strives to expand transdisciplinary collaborations and communications to improve health care for humans, animals, and the environment.17 This defining theme is rather analogous to conservation medicine.

It is easy to appreciate that these approaches have many similarities; both have the objective to improve the health of animals and humans while recognizing the constant interplay and growing interconnections among animals, humans, and ecosystems. In fact, One Health might be viewed as having evolved from conservation medicine, triggered by the growing realization that EIDs in humans are largely of zoonotic origin.16 One Health initiatives now support the use of animal and human disease models, as well as the use of animals and humans as sentinels for each other to advance the understanding of diseases to benefit all animal species and to emphasize the need for preventive measures that minimize the spread of pathogens across species.34

It is more important to develop programs that fit into both the conservation medicine and One Health paradigms rather than picking either term for describing a program. Zoologic veterinarians practice both conservation medicine and One Health. However, it is important that all these programs do consider the relationship between the health of animals and that of humans, and how environmental conditions play a vital role in the health of all species. In the years to come, the tougher challenges for effective conservation medicine and One Health approaches may be related to the ethics of efforts with different cost–benefit ratios for the different groups of interest (i.e., animals, humans, and ecosystems). Significant health benefits to one may be at the cost of another. One example may be public health measures that involve large scale culling of wildlife in an effort to protect human health but which may ultimately result in damage to the health of other species, to the ecosystems, and possibly to humans as well. As zoologic veterinarians practicing conservation medicine and One Health, it is important to remain true to the underlying objectives of these transdisciplinary approaches and work to ensure the conservation of biodiversity.

Opportunities for Zoological Institutions

While the number of species threatened by extinction grows daily, accredited zoologic institutions are now being fully recognized as conservation organizations. In this chapter, the word accredited will refer to the approximately 218 zoos and aquariums accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), other regional zoo organizations, and the approximately 300 organizations accredited by the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA). The term zoologic veterinarian will refer to zoologic and aquarium veterinarians. Unlike many other conservation organizations, zoos are often seen as organizations that work for species survival and that are dedicated to the long-term conservation of wildlife species. One example is the documentation that of the 68 species which had their conservation threat level reduced by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the reduction for 17 (25%) of these species was associated with captive breeding efforts at zoologic institutions.4

As accredited zoos are being increasingly recognized for their conservation initiatives, it has also become evident that this leadership role of zoos in the conservation of species developed along with advancements in health care that ensured population viability. Veterinary sciences, which were previously overlooked as being instrumental in the role of zoos in the conservation of species, are now seen as imperative for conservation efforts and the long-term survival of populations in zoo collections and of free-living populations.11,24 In fact, one of the key reasons that zoos are successful conservation organizations is related to the veterinary care provided to animals in collections and to field-based health studies that improve conservation efforts and provide comparative health data for free-living and collection populations.11 Today, with the push for AZA-accredited zoos to dedicate 3% of their revenue to conservation, the time is right for zoos to also show their leadership roles in conservation medicine and One Health initiatives. In fact, a core objective of a zoo conservation program is often to ensure healthy wildlife populations and ecosystems without compromising the health of humans, and thus the conservation mission of accredited zoos fits perfectly within the objectives of conservation medicine and One Health. Furthermore, to attain accreditation, zoos must have animal care providers and veterinary clinicians on staff. Often zoos also have epidemiologists, nutritionists, reproductive physiologists, pathologists, endocrinologists, geneticists, education specialists, public relations experts, and animal behaviorists on staff, all equipped to advance the conservation medicine and One Health objectives.

Roles of Zoologic Veterinarians in Conservation Medicine and One Health

The education, experiences, and responsibilities of zoologic veterinarians position them as key players in the transdisciplinary approaches of conservation medicine and One Health. In fact, the role of zoologic veterinarians has been well-represented in conservation medicine over the last 15 years and is now also recognized in One Health.7,10,11,15,39 Zoos today are much more than simple “arks” of protection for threatened and endangered wildlife, and staff provide health care and conduct health studies on animals both within zoo walls (ex situ) and in the wild (in situ).11 As we move forward and strengthen the efforts of zoologic veterinarians in these initiatives, it will be important to develop strong relationships between successful zoo-based conservation medicine and One Health activities across the entire zoologic community and in the conservation medicine and One Health communities.7,39

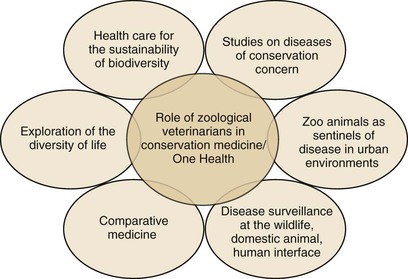

The significant contributions of zoologic veterinarians to conservation medicine and One Health and the benefits that zoos offer to both biodiversity conservation and human health may be categorized into five roles: (1) providing healthcare for zoologic species, thus ensuring sustainability of biodiversity; (2) conducting studies on diseases of conservation concern; (3) understanding diseases in zoo wildlife as sentinels for emerging diseases of humans and animals in surrounding areas; (4) performing surveillance of diseases in wild animals at the interface of wildlife, domestic animals, and humans; and (5) making contributions to the fields of comparative medicine and the discovery of all life forms (Figure 73-1 and Box 73-1).

Providing Healthcare for Zoo Wildlife to Ensure Sustainability of Biodiversity

Accredited zoos have succeeded in their efforts to bring some species back from the brink of extinction for many intersecting reasons. One reason is the advances in veterinary care, including preventive and therapeutic care to minimize the negative impacts of infectious and noninfectious diseases. Similar to public health programs (e.g., vaccination and proper nutrition) that were instrumental in the human population reaching beyond seven billion individuals, these veterinary health care methods have been essential for the propagation of species. Now as wild spaces are being reduced and free-living wildlife often live within habitats that are little more than large zoos, these veterinary advancements, many of which are first developed with zoo collection animals, are also being used for the long-term survival of populations in the wild.11 Lastly, a number of reintroduction programs such as those for black-footed ferrets, red wolves, Hawaiian songbirds, and freshwater mussels have resulted in the propagation of species at accredited zoos and successful placement back in the wild (http://www.aza.org/reintroduction-programs/). The successes of these (and many other) reintroduction programs were only possible when health challenges were appropriately addressed within the reintroduction plans in conjunction with other important program components.

Conducting Studies on Diseases of Conservation Concern

Zoos conduct studies to better understand the clinical impacts, epidemiology, and pathology of diseases that have population impacts and, in some cases, species-level impacts. Diseases in wildlife species have now been documented to impact the survival of species with both population extirpations and even species extinctions.6,30 Many of the infectious diseases that threaten the long-term survival of wildlife species, including fibropapillomatosis in sea turtles, chytridiomycosis in amphibians, canine distemper in a number of carnivores, and Ebola virus in humans and animals are studied by zoologic health professionals.6,9 Disease-related conservation challenges are not solely linked to infectious diseases, possibly best exemplified by the near-extinction of three Gyps spp. in India associated with the use of an anti-inflammatory drug in livestock.28 Whether infectious or noninfectious, diseases may have impacts on multiple scales, affecting individuals (fitness costs), populations (population size and connection), communities (changes in species composition), and ecosystems (structure, function, and resilience).8 The epidemiology, pathology, and clinical implications of many of these significant disease challenges are studied extensively by zoo health professionals, both in situ and ex situ.25,35 These scientific investigations are often turned into conservation actions implemented by zoos to minimize the negative impacts identified by these studies.

Benefits gained from these zoo-led studies are many and include the sustainability of biodiversity, which may help ensure the continuation of ecosystem services provided by biodiversity such as the prevention of disease. The recently recognized “dilution” effect, in which a larger assembly of species (increased biodiversity), each with different disease susceptibilities, may minimize emerging infectious diseases of humans and other animals, is a great example of how zoo-based studies to better manage diseases of conservation concern may have broad-reaching, cross species health implications.18

Understanding Diseases in Zoo Wildlife as Sentinels for Emerging Diseases of Humans and Animals

Animals cared for in accredited zoos include a variety of nondomestic species, with differing susceptibilities to infectious and noninfectious diseases. These zoo animals provide a sentinel system for the regions where they are housed. Animals in accredited zoos receive veterinary care, documented in medical records, and contribute to blood and tissue banks, both of which offer a sustainable epidemiologic monitoring system that may be beneficial for animal and public health. One example is the Lincoln Park Zoo Davee Center for Epidemiology and Endocrinology, which coordinates national efforts of accredited zoos in the United States to serve as sentinels by testing and monitoring for zoonotic disease outbreaks.

A well-known example of zoo animals serving as sentinels is the detection of West Nile virus (WNV) at a zoo in New York State, which led to the zoo community alerting other human and animal health communities to the arrival of this vector-borne pathogen to the New World.22,33 The network of accredited zoologic parks in the United States and Europe now have surveillance programs for zoonotic pathogens such as avian influenza virus and WNV, linking zoos and effectively covering continents.3,33 Additionally, many zoos in North America have surveillance programs for urban wildlife on and near zoo grounds for zoonotic pathogens such as rabies virus and Baylisascaris procyonis. Lastly, with the sophisticated record keeping capabilities of these institutions, along with the careful pathologic evaluations at necropsy, the ability to better understand trends in potential noninfectious health concerns shared by animals and humans (e.g., cancers and toxins) is also explored at zoologic institutions. Veterinary staff members at accredited zoos often have ties with doctors in human medicine, thus ensuring communication of comparative findings from zoo animals and human patients in the region. This collaborative work between the human and veterinary medical fields may serve as an early warning system for diseases of concern for both animals and humans.

Surveillance of Disease in Wild Animals at the Interface of Wildlife, Domestic Animals, and Humans

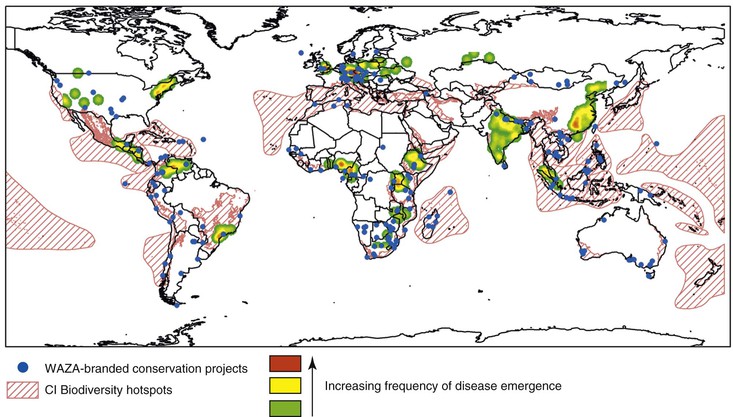

Staff members of accredited zoos conduct conservation studies that give zoos a global footprint. For example, an overlay of 113 WAZA-branded projects with documented biodiversity and emerging disease hotspots demonstrates that this footprint includes regions of significant conservation and human health concerns (Figure 73-2).14,16,26 The often long-term commitments to field conservation and research from these zoo-led programs provide a means for zoo staff to perform health surveillance studies that may include species of conservation interest and sympatric species. A number of these in situ studies also have a human health component, as many of the pathogens of interest are zoonotic and may spillover and spillback among wild populations, domestic animals, and humans sharing the habitat.2,20

Contributing to the Field of Comparative Medicine and the Discovery of All Life Forms

Comparative medicine, a long-established field within both the veterinary and human medical professions, is based on comparisons and contrasts of the anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology of diseases of humans and other species. Advances in human medicine are largely from comparative studies based on animal models. Today, growing applications of human studies promote understanding of the diseases of animals (e.g., cancers, arthritis) and the use of sentinel animals and humans for the health of each other.34 The role zoos play in the field of comparative medicine was underutilized in the past; however, it is now being increasingly documented. Zoos and the animals in their care are important in comparative medicine studies and have gained crossover appreciation by both veterinary and human medical professionals and a general nonmedical audience.27

In biodiversity conservation, much emphasis has been placed on the long-term survival of vertebrate species, with lesser emphasis on invertebrate conservation and even less on the conservation of microorganisms. However, without microorganisms, biodiversity would not exist. Species are metagenomic in that they are composed of their own gene complements and those of all their associated microbes. Each species—in fact, each individual—is known to have unique “microbiomes.” One study of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences from a variety of zoologic animals demonstrated that host diet and phylogeny both influence bacterial diversity while adding new microbial species to the list of life forms on Earth.21 Accredited zoos, with their collections of diverse species and their outreach across the globe through studies on free-living wildlife populations, can, and must, contribute to the exploration of the diversity of life at the microbial level.

Conclusion

In this chapter, roles that zoologic veterinarians have to contribute within conservation medicine and One Health approaches were discussed. Zoologic veterinarians will continue to serve as key players dedicated to the conservation of biodiversity and as health care providers for animals, ecosystems, and humans. They also will fully participate in conservation medicine and One Health initiatives. In addition to these roles, zoologic veterinarians must be educators, disseminating the message about the health continuum that exists among people, animals, and the ecosystems that support biodiversity.

During the past decades, as conservation medicine and One Health initiatives gained global support, the conservation and health challenges that engendered these approaches have also continued to grow. The increasing evidence of global climate change impacts, including the hottest year in recorded history for the United States, EID issues with the worst year of human West Nile virus cases in the United States, and the documentation of increases in the illegal trade in wildlife species all clearly demonstrate these challenges. The need for practicing conservation medicine and One Health approaches and bringing these efforts into the mainstream has never been more pressing, and zoologic veterinarians are in a key position to meet this need.

Since the 1990s, ecologists have embraced the conservation medicine movement, with disease ecology recognized as an important new subspecialty within the study of ecology. In the past few years, the human medical establishment has become increasingly aware of the link between human and animal health and the need to approach human health in a more ecologic context. It is imperative that zoologic veterinarians continue to be active participants in these efforts and that they work on projects that ensure the health of all—the animals in their direct care, the humans that interact with these animals, and the habitats that sustain all life on Earth.