2 THE LATERAL CXR

Patient with a persistent cough. Normal clinical examination.

The novice may feel that getting to grips with the lateral CXR is too much at this stage. Don’t worry. Keep going on the other chapters and come back to the lateral CXR later on. Eventually, you will realise its importance. Also, analysing the lateral CXR is fun—Sherlock Holmes type fun.

Reference drawings of the normal lateral appearance are provided on p. viii.

RADIOGRAPHIC TECHNIQUE

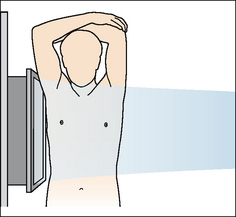

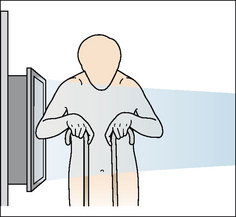

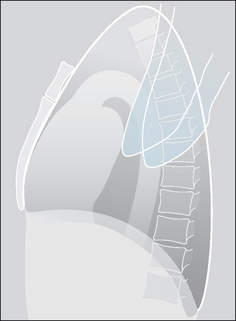

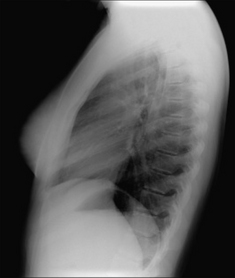

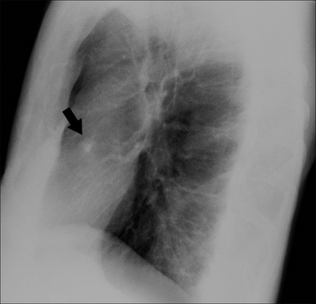

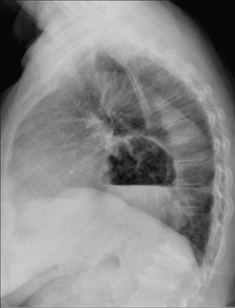

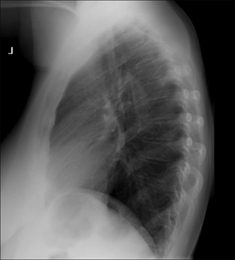

In a fit individual the arms are held high and well away from the thorax(Fig. 2.1). In a frail or elderly patient the arms may have to be positioned in front of the chest. The resulting upper arm shadows can mislead the unwary (Fig. 2.2). The scapulae cannot avoid intruding on the image, but they should be easy to recognise (Figs 2.3 and 2.4).

UNDERSTANDING THE LATERAL CXR2-6

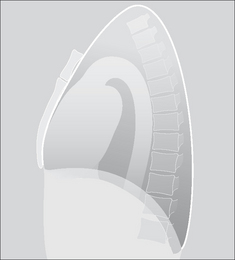

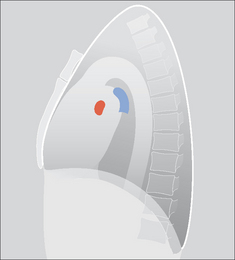

Figs 2.5-2.9 show how you can build up the main anatomical structures on a lateral CXR. Fig. 2.10 is the radiographic equivalent of the finished article.

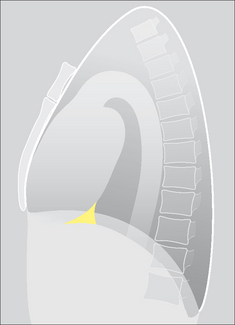

Figure 2.5 Bare-bones lateral anatomy. Note that the lungs appear blacker inferiorly as compared with superiorly.

Figure 2.8 …add—in your mind’s eye—the three fissures. Knowing their approximate position is important. They separate the three lobes of the right lung and the two lobes of the left lung. In practice, it is rare for much of either oblique fissure to be visualised on a normal lateral CXR.

NORMAL LATERAL CXR—SPECIFIC APPEARANCES

DIAPHRAGM

The two domes are usually easy to separate from each other.

The shadow of the left dome only extends from the costophrenic recess posteriorly to the back of the cardiac shadow anteriorly. This is because the heart obliterates the lung/diaphragm interface anteriorly.

The shadow of the left dome only extends from the costophrenic recess posteriorly to the back of the cardiac shadow anteriorly. This is because the heart obliterates the lung/diaphragm interface anteriorly.

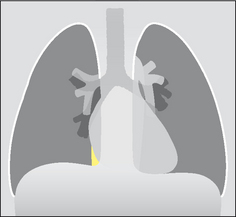

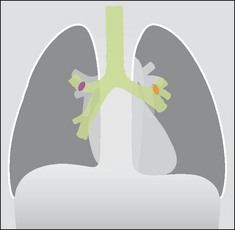

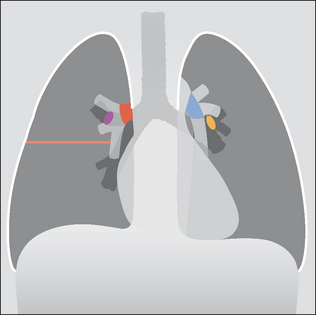

Figure 2.11 Normal structures as seen on the frontal CXR, for comparison with Figs 2.5-2.10. Red = right main pulmonary artery; blue = left main pulmonary artery; purple = origin of right upper lobe bronchus; yellow = origin of left upper lobe bronchus.

Very occasionally the two domes are difficult to separate, because:

HILA

The novice will find this a difficult area to assess. Bear these points in mind:

Of the soft tissue density at each hilum, 95% is due solely to pulmonary artery and pulmonary veins.

Of the soft tissue density at each hilum, 95% is due solely to pulmonary artery and pulmonary veins. The main pulmonary artery on the right side passes anterior to the right main bronchus, whereas the main pulmonary artery on the left side passes posteriorly and hooks over the left main bronchus.

The main pulmonary artery on the right side passes anterior to the right main bronchus, whereas the main pulmonary artery on the left side passes posteriorly and hooks over the left main bronchus. There is summation of some of the left and right hilar densities (i.e. the vessels) on the lateral CXR.

There is summation of some of the left and right hilar densities (i.e. the vessels) on the lateral CXR.You will be delighted to know that even the experts find this area difficult. However, the expert always evaluates the lateral view of a hilum together with the frontal projection. By taking the two views together it is much, much easier to answer a frequent question: “is this hilum enlarged or is it just prominent but normal?”.

LUNG FISSURES

The horizontal fissure can be identified on most lateral CXRs (Fig. 2.15).

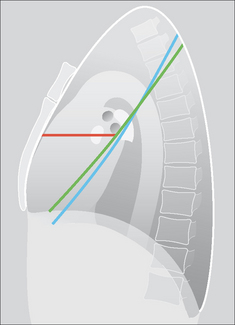

Figure 2.15 The three fissures. Red = horizontal; green = right oblique; blue = left oblique. Visibility of the fissures varies from patient to patient—some, all, or none of a fissure may be evident. The fissures divide each lung into lobes. The right lung has three lobes—upper, middle and lower. The left lung has two lobes—upper and lower. (See p. viii.)

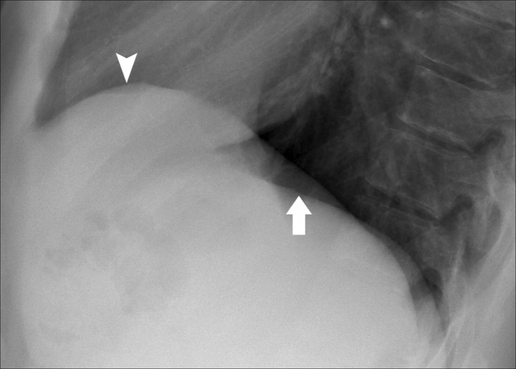

The oblique fissures are not aligned along a flat plane. Both have configurations similar to that of an aeroplane propeller (Fig. 2.16).

Figure 2.16 The normal configuration of an oblique fissure. Each oblique fissure resembles an aeroplane propeller.

It is often stated that the right oblique fissure lies—at its most inferior position—about 4–5 cm posterior to the sternum, and that the left oblique fissure is positioned slightly more posterior. In practice, very slight rotation of the patient can project these fissures closer to, or further away from, each other on the CXR. The good news is that absolute certainty as to which oblique fissure is which is rarely important in clinical practice.

COSTOPHRENIC ANGLES (RECESSES, SULCI)

The posterior and inferior part of each lung occupies a well-defined gully created by the pleura reaching the posterior limit of each dome of the diaphragm. These two gullies—one on each side—are the costophrenic angles or sulci (Figs 2.15 and 2.16).

On the lateral radiograph, each costophrenic recess represents the most inferior aspect of the lung and pleura on an erect CXR. This is where most pleural effusions will collect.

LUNG APICES

The lateral CXR is not much help in assessing either lung apex, due to the overlying soft tissues, shoulders and chest wall.

RETROSTERNAL LINE

A soft tissue interface with the lung is visible immediately behind the sternum (Fig. 2.17). This is the retrosternal line.

The line is caused by the interface between the retrosternal soft tissues (mainly fat) and the anterior aspect of the right lung.

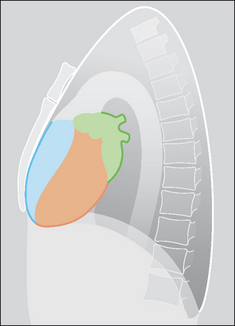

HEART

The heart occupies most of the mediastinum (Figs 2.19 and 2.20). The cardiac borders seen on the lateral CXR are formed as follows:

Figure 2.19 Cardiac chambers. Frontal CXR allows correlation with the lateral CXR (Fig. 2.20). Pink = right atrium; blue = right ventricle; brown = left ventricle; green = left atrium.

INFERIOR VENA CAVA

On many lateral CXRs a short (1.5–2.0 cm) well-defined vertical shadow meets the posterior and inferior aspect of the heart. This shadow is the inferior vena cava. Its posterior wall is visible because it is outlined by air in the adjacent right lung (see Figs 2.21-2.23).

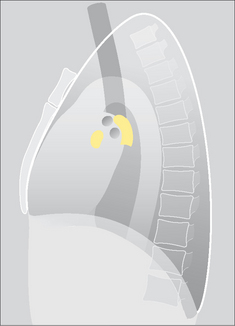

TWO BRONCHIAL RINGS

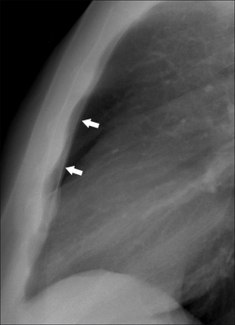

Two circular rings are often projected over the hila or peri-hilar regions(Figs 2.24-2.26). Sometimes only one ring is visible. Usually the higher ring is the right upper lobe bronchus and the lower ring is the left upper lobe bronchus.

Figure 2.24 Normal lateral CXR. Trachea = green; right upper lobe bronchus (seen end on) = purple; left upper lobe bronchus (seen end on) = brown.

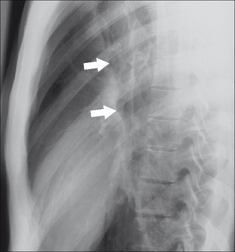

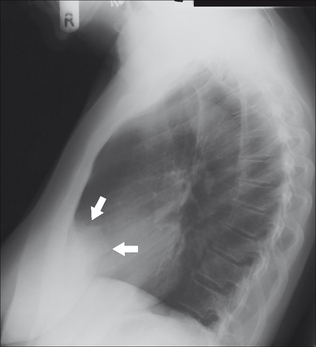

Figure 2.26 The two rings (arrows) are visible in this patient. The rings represent—in almost all patients—the orifices of the upper lobe bronchi. Occasionally, they represent the main bronchi2.

BONES AND SOFT TISSUES

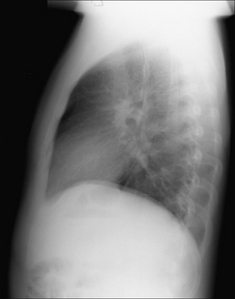

All lateral CXRs include part of the axial and appendicular skeleton. Bones will occasionally cause an overlap shadow. Familiarity with the normal skeletal appearances will prevent misunderstandings. Note:

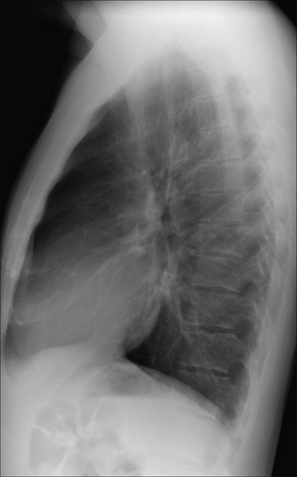

Figure 2.27 Normal CXR. The lower vertebral bodies are blacker because there is less soft tissue (muscle) and no scapulae superimposed. Consequently, there is less absorption of the x-ray beam inferiorly, and thus more blackening on the radiograph. Whiteness inferiorly on the CXR invariably indicates pathology (e.g. collapse, consolidation, lung mass, paravertebral mass). Also, note that assessment of a lung apex is very difficult—usually impossible.

NORMAL LATERAL CXR—THREE COMMON PITFALLS

Figure 2.33 Age 80. Age related aortic unfolding occurs in the middle-aged and elderly. The descending aorta is outlined by lung and is visible (arrows). (This is the same patient as Fig. 2.31.)

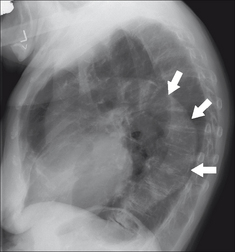

Figure 2.34 The cardiac incisura. The anterior density (arrows) is caused by the normal cardiac apex and epicardial fat displacing the most infero-medial and anterior aspect of the left lung. The shape of the cardiac incisura will show considerable variation between patients. (Incidentally, a cardiac incisura shadow, with a somewhat different contour is also shown in Fig. 2.33, above.)

READING THE LATERAL CXR

A lateral radiograph of the chest can be very valuable in helping to confirm, refute, position or characterise a suspected abnormality seen on the frontal projection. A checklist will help you to remember the important rules.

THE LATERAL CXR: A SIX-POINT CHECKLIST

Remember—the right dome should be visible from front to back; normally the anterior aspect of the left dome disappears (Fig. 2.35).

Remember—the right dome should be visible from front to back; normally the anterior aspect of the left dome disappears (Fig. 2.35).

Figure 2.35 Normal CXR. Note that the vertebral bodies become blacker from above downwards; the domes of the diaphragm are well-defined.

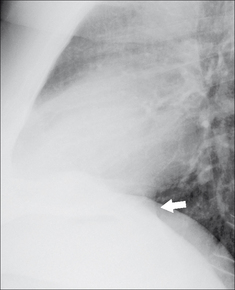

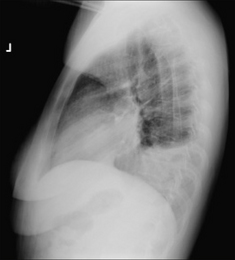

Figure 2.36 Cough and fever. Vertebrae whiter inferiorly. The outline of the left dome of the diaphragm is absent posteriorly. Left lower lobe pneumonia.

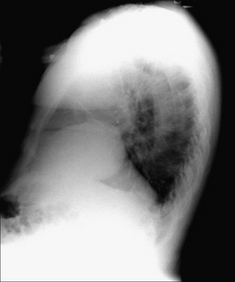

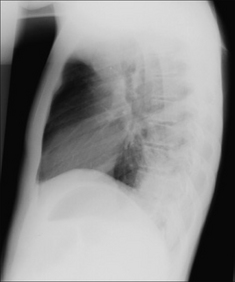

Figure 2.37 Unwell, fever, chest pain. Vertebrae whiter inferiorly; the outline of the right dome of the diaphragm is absent posteriorly. Right lower lobe pneumonia.

1. Henry S Haskins. American author (b.1875).

2. Proto AV, Speckman JM. The left lateral radiograph of the chest. Part one. Med Radiogr Photogr. 1979;55:30-74.

3. Proto AV, Speckman JM. The left lateral radiograph of the chest. Part two. Med Radiogr Photogr. 1980;56:38-64.

4. Austin JHM. The lateral chest radiograph in the assessment of non-pulmonary health and disease. Radiol Clin North Am. 1984;22:687-698.

5. Vix VA, Klatte EC. The lateral chest radiograph in the diagnosis of hilar and mediastinal masses. Radiology. 1970;96:307-316.

6. Fraser RG, Muller NL, Colman NC, Pare PD. Fraser and Pare’s Diagnosis of Diseases of the Chest, 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1999.

7. Heitzman ER. The Mediastinum. St Louis, MO: Mosby, 1977.

8. Hyson EA, Ravin CE. Radiographic features of mediastinal anatomy. Chest. 1979;75:609-613.