Chapter 26 Eating Disorders

Eating disorders (EDs) are characterized by body dissatisfaction related to overvaluation of a thin body ideal associated with dysfunctional patterns of cognition and weight control behaviors that results in significant biologic, psychologic, and social complications. Although largely affecting white, adolescent girls, EDs also affect boys and cross all racial, ethnic, and cultural boundaries. Early intervention in EDs improves outcome.

Definitions

Anorexia nervosa (AN) involves significant overestimation of body size and shape, with a relentless pursuit of thinness that typically combines excessive dieting and compulsive exercising in the restrictive subtype; in the binge-purge subtype, patients might intermittently overeat and then attempt to rid themselves of calories by vomiting or taking laxatives, still with a strong drive for thinness (Table 26-1). Bulimia nervosa (BN) is characterized by episodes of eating large amounts of food in a brief period, followed by compensatory vomiting, laxative use, and exercise or fasting to rid the body of the effects of overeating in an effort to avoid obesity (Table 26-2).

Table 26-1 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR 307.1 ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Specify Type:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4, Washington, DC, 1994, American Psychiatric Association.

Table 26-2 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR 307.51 BULIMIA NERVOSA

Specify Type:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4, Washington, DC, 1994, American Psychiatric Association.

The majority of children and adolescents with EDs do not fulfill all of the criteria for either of these syndromes in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) classification system but fall instead into the category of eating disorder, not otherwise specified (ED-NOS) (Table 26-3). ED-NOS includes a wide variety of subthreshold clinical presentations. Binge eating disorder (BED), in which binge eating is not followed regularly by any compensatory behaviors, is included in ED-NOS in DSM-IV and shares many features with obesity (Chapter 44). ED-NOS, often called “disordered eating,” can worsen into full syndrome EDs.

Table 26-3 307.50 EATING DISORDER NOT OTHERWISE SPECIFIED

The Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified category is for disorders of eating that do not meet the criteria for any specific Eating Disorder. Examples include:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4, Washington, DC, 1994, American Psychiatric Association.

Epidemiology

The classic features of AN include a white, early to middle adolescent girl of above-average intelligence and socioeconomic status, who is a conflict-avoidant, risk-aversive, perfectionist struggling with disturbances of anxiety and/or mood. BN tends to emerge in later adolescence, sometimes evolving from AN, and is typified by impulsivity and features of borderline personality disorder that are associated with depression and mood swings. The 0.5-1% and 3-5% incidence rates among younger and older adolescent girls for AN and BN, respectively, probably reflect ascertainment bias in sampling and underdiagnosis in cases not fitting the typical profile. The same may be true of the significant gender disparity, in which female patients account for about 90% of patients with diagnosed EDs. Ten percent or more of some adolescent female populations have ED-NOS.

No single factor causes the development of an ED; sociocultural studies indicate a complex interplay of culture, ethnicity, gender, peers, and family. The gender dimorphism is presumably related to girls having a stronger relationship between body image and self-evaluation, as well as the influence of the Western culture’s thin body ideal on the development of EDs. Race and ethnicity appear to moderate the association between risk factors and disordered eating, with African-American and Caribbean girls reporting lower body dissatisfaction and less dieting than Hispanic and non-Hispanic white girls. Because peer acceptance is central to healthy adolescent growth and development, especially in early adolescence when AN tends to have its initial prevalence peak, the potential influence of peers on EDs is significant, as are the relationships among peers, body image, and eating. Teasing by peers or by family members (especially male) may be a contributing factor for overweight girls.

Family influence in the development of EDs is even more complex because of the interplay of environmental and genetic factors; shared elements of the family environment and immutable genetic factors account for significant (about equal) variance in disordered eating. There are associations between parents’ and children’s eating behaviors; dieting and physical activity levels suggest parental reinforcement of body-related societal messages. The influence of inherited genetic factors on the emergence of EDs during adolescence is also significant, but not in a direct fashion. Rather, the risk for developing an ED appears to be mediated through a genetic predisposition to anxiety (Chapter 23), depression (Chapter 24), or obsessive-compulsive traits that may be modulated through the internal milieu of puberty. There is little evidence that parents “cause” an ED in their child or adolescent; the importance of parents in treatment and recovery cannot be overestimated.

Pathology and Pathogenesis

The emergence of EDs coinciding with the processes of adolescence (e.g., puberty, identity, autonomy, cognition) indicates the central role of development. A history of sexual trauma is not significantly more common in EDs than in the population at large, but when present it makes recovery more difficult and is more common in BN. EDs may be viewed as a final common pathway, with a number of predisposing factors that increase the risk of developing an ED, precipitating factors often related to developmental processes of adolescence triggering the emergence of the ED, and perpetuating factors that cause an ED to persist. EDs often begin with dieting but gradually progress to unhealthy habits that lessen the negative impact of associated psychosocial problems to which the affected person is vulnerable because of premorbid biologic and psychologic characteristics, family interactions, and social climate.

When persistent, the biologic effects of starvation and malnutrition (e.g., true loss of appetite, hypothermia, gastric atony, amenorrhea, sleep disturbance, fatigue, weakness, and depression) combined with the psychologic rewards of increased sense of mastery and reduced emotional reactivity, actually maintain and reward pathologic ED behaviors. This positive reinforcement of behaviors and consequences, generally viewed by parents and others as negative, helps to explain why affected persons characteristically deny that a problem exists and resist treatment. Though noxious, purging can be reinforcing due to reduction in anxiety triggered by overeating; purging also can result in short-term, but reinforcing, improvement in mood that is related to changes in neurotransmitters. In addition to an imbalance in neurotransmitters, most notably serotonin and dopamine, there are also alterations in functional anatomy that support the concept of EDs as brain disorders. The cause-and-effect relationship in central nervous system (CNS) alterations in EDs is not clear, nor is their reversibility.

Clinical Manifestations

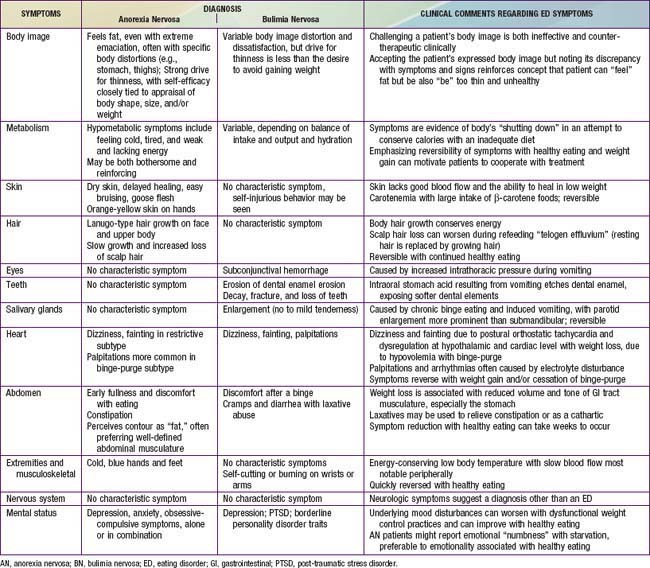

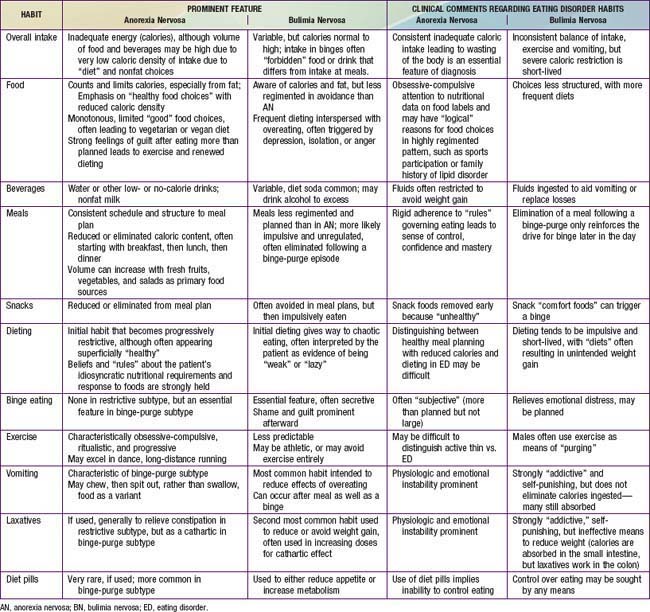

A central feature of EDs is the overestimation of body size, shape or parts (e.g., abdomen, thighs) leading to weight-control practices intended to reduce weight (AN) or prevent weight gain (BN). Associated practices include severe restriction of caloric intake and behaviors intended to reduce the effect of calories ingested, such as compulsive exercising or purging by inducing vomiting or taking laxatives. Eating and weight loss habits commonly found in EDs can result in a wide range of energy intake and output, the balance of which leads to a wide range in weight from extreme loss of weight in AN to fluctuation around a normal to moderately high weight in BN. Reported eating and weight-control habits (Table 26-4) thus inform the initial primary care approach.

Table 26-4 EATING AND WEIGHT CONTROL HABITS COMMONLY FOUND IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS WITH AN EATING DISORDER

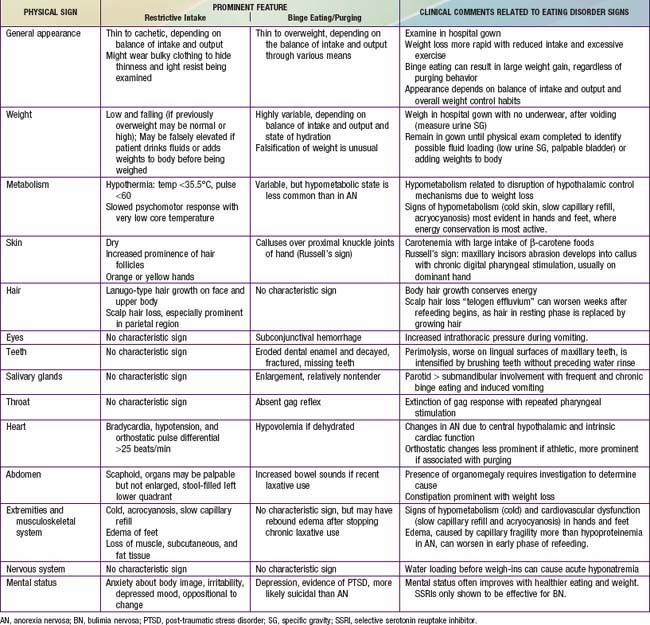

Although weight-control patterns guide the initial pediatric approach, an assessment of commonly reported symptoms and findings on physical examination is essential to identify targets for intervention. When reported symptoms of excessive weight loss (feeling tired and cold; lacking energy; orthostasis; difficulty concentrating) are explicitly linked by the clinician to their associated physical signs (hypothermia with acrocyanosis and slow capillary refill, loss of muscle mass, bradycardia with orthostasis), it becomes more difficult for the patient to deny that a problem exists. Furthermore, awareness that bothersome symptoms can be eliminated by healthier eating and activity patterns can increase a patient’s motivation to engage in treatment. Tables 26-5 and 26-6 detail common symptoms and signs that should be addressed in a pediatric assessment of a suspected ED.

Differential Diagnosis

In addition to identifying symptoms and signs that deserve targeted intervention for patients who have an ED or disordered eating, a comprehensive history and physical examination are required in the assessment of a suspected ED to rule out other conditions in the differential diagnosis. Weight loss can occur with any condition in which there is increased catabolism (e.g., malignancy or occult chronic infection) or malabsorption (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease or celiac disease), but these illnesses are generally associated with other findings and are not usually associated with decreased caloric intake. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease can reduce intake to minimize abdominal cramping; eating can cause abdominal discomfort and early satiety in AN because of gastric atony associated with significant weight loss, not malabsorption. Likewise, signs of weight loss in AN might include hypothermia, acrocyanosis with slow capillary refill, and neutropenia suggesting overwhelming sepsis, but the overall picture in EDs is one of relative cardiovascular stability compared to sepsis. Endocrinopathies are also in the differential of EDs. With BN, voracious appetite in the face of weight loss might suggest diabetes mellitus, but blood glucose levels are normal or low in EDs. Adrenal insufficiency mimics many physical symptoms and signs found in restrictive AN but is associated with elevated potassium levels and hyperpigmentation. Although thyroid disorders are often considered, due to changes in weight and other symptoms in AN, the overall presentation includes symptoms of both underactive and overactive thyroid, such as hypothermia, bradycardia, and constipation, as well as weight loss and excessive physical activity, respectively.

In the CNS, craniopharyngiomas and Rathke pouch tumors can mimic some of the findings of AN, such as weight loss and growth failure, and even some body image disturbances, but the latter are less fixed than in typical EDs and are associated with other findings, including evidence of increased intracranial pressure. Any patient with an atypical presentation of an ED, based on age, sex, or other factors not typical for AN or BN deserves a scrupulous search for an alternative explanation. Patients can have both an underlying illness and an ED. The core features of dysfunctional eating habits—body image disturbance and change in weight—can coexist with conditions such as diabetes mellitus, where patients might manipulate their insulin dosing to lose weight.

Laboratory Findings

Because the diagnosis of an ED is made clinically, there is no confirmatory laboratory test. Laboratory abnormalities, when found, are due to malnutrition, weight control habits used, or medical complications; studies should be chosen based on history and physical examination. A routine screening battery typically includes complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (should be normal), and biochemical profile. Common abnormalities in ED include low white blood cell count with normal hemoglobin and differential; hypokalemic, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis with severe vomiting; mildly elevated liver enzymes, cholesterol, and cortisol levels; low gonadotropins and blood glucose with marked weight loss; and generally normal total protein, albumin, and renal function. An electrocardiogram (ECG) may be useful when profound bradycardia or arrhythmia is detected; the ECG usually has low voltage, with nonspecific ST or T wave changes. Although prolonged QTc has been reported, prospective studies have not found an increased risk for this.

Complications

No organ is spared the harmful effects of dysfunctional weight control habits, but the most concerning targets of medical complications are the heart, brain, gonads, and bones. Some heart findings in EDs (e.g., sinus bradycardia and hypotension) are physiologic adaptations to starvation that conserve calories and reduce afterload. Cold, blue hands and feet with slow capillary refill that can result in tissue perfusion insufficient to meet demands also represent energy-conserving responses associated with inadequate intake. All of these acute changes are reversible with restoration of nutrition and weight. Significant orthostatic pulse changes, prolonged corrected QT interval, ventricular dysrhythmias, or reduced myocardial contractility reflect myocardial impairment that can be lethal. In addition, with extremely low weight, refeeding syndrome (due to rapid drop in serum phosphorous, magnesium, and potassium with excessive reintroduction of calories, especially carbohydrates), is associated with acute heart failure and neurologic symptoms. With long-term malnutrition, the myocardium appears to be more prone to tachyarrhythmias, the second most common cause of death after suicide. In BN, dysrhythmias can also be related to electrolyte imbalance.

Clinically, the primary brain area affected acutely in EDs, especially with weight loss, is the hypothalamus. Hypothalamic dysfunction is reflected in problems with thermoregulation (warming and cooling), satiety, sleep, autonomic cardioregulatory imbalance (orthostasis) and endocrine function (reduced gonadal and excessive adrenal cortex stimulation), all of which are reversible. Anatomic studies of the brain in ED have focused on AN, with the most common finding being increased ventricular and sulcal volumes that normalize with weight restoration. Persistent gray-matter deficits following recovery, related to the degree of weight loss, have been reported. Elevated medial temporal lobe cerebral blood flow on positron emission tomography (PET) similar to that found in psychotic patients suggests that these changes may be related to body image distortion. Also, visualizing high-calorie foods is associated with exaggerated responses in the visual association cortex that are similar to those seen in patients with specific phobias. Patients with AN might have an imbalance between serotonin and dopamine pathways related to neurocircuits in which dietary restraint reduces anxiety.

Reduced gonadal function occurs in male and female patients; it is clinically manifested in AN as amenorrhea in female patients. It is related to understimulation from the hypothalamus as well as cortical suppression related to physical and emotional stress. Amenorrhea precedes significant dieting and weight loss in up to 30% of females with AN, and most adolescents with EDs perceive the absence of menses positively. The primary health concern is the negative effect of decreased ovarian function and estrogen on bones. Decreased bone mineral density (BMD) with osteopenia or the more severe osteoporosis is a significant complication of EDs (more pronounced in AN than BN). Data do not support the use of sex hormone replacement therapy because this alone does not improve other causes of low BMD (low body weight, lean body mass, and insulin-like growth factor [IGF]-1; high cortisol).

Treatment

Principles Guiding Primary Care Treatment

The approach in primary care should facilitate the acceptance by the patient (and parents) of the diagnosis and initial treatment recommendations. A nurturant-authoritative approach using the biopsychosocial model is useful. A pediatrician who explicitly acknowledges that the patient may disagree with the diagnosis and treatment recommendations and be ambivalent about changing eating habits, while also acknowledging that recovery requires strength, courage, will-power and determination, demonstrates nurturance. Parents also find it easier to be nurturant once they learn that the development of an ED is neither a willful decision by the patient nor a reflection of bad parenting. Framing the ED as a coping mechanism for a complex variety of issues with both positive and negative aspects avoids blame or guilt and can prepare the family for professional help that will focus on strengths and restoring health, rather than on the deficits in the adolescent or the family.

The authoritative aspect of a physician’s role comes from expertise in health, growth, and physical development. A goal of primary care treatment should be attaining and maintaining health—not merely weight gain—although weight gain is a means to the goal of wellness. Providers who frame themselves as consultants to the patient with authoritative knowledge about health can avoid a countertherapeutic authoritarian stance. Primary care health-focused activities include monitoring the patient’s physical status, setting limits on behaviors that threaten the patient’s health, involving specialists with expertise in EDs on the treatment team, and continuing to provide primary care for health maintenance, acute illness, or injury.

The biopsychosocial model uses a broad ecologic framework, starting with the biologic impairments of physical health related to dysfunctional weight control practices, evidenced by symptoms and signs. Explicitly linking ED behaviors to symptoms and signs can increase motivation to change. In addition, there are usually unresolved psychosocial conflicts in both the intrapersonal (self-esteem, self-efficacy) and interpersonal (family, peers, school) domains. Weight-control practices initiated as coping mechanisms become reinforced because of positive feedback. That is, external rewards (e.g., compliments about improved physical appearance) and internal rewards (e.g., perceived mastery over what is eaten or what is done to minimize the effects of overeating through exercise or purging) are more powerful to maintain behavior than negative feedback (e.g., conflict with parents, peers, and others about eating) is to change it. Thus, when definitive treatment is initiated, more productive alternative means of coping must be developed.

Nutrition and Physical Activity

The primary care provider generally begins the process of prescribing nutrition, although a dietitian should be involved eventually in the meal planning and nutritional education of patients with AN or BN. Framing food as fuel for the body and the source of energy for daily activities emphasizes the health goal of increasing the patient’s energy level, endurance, and strength. For patients with AN and low weight, the nutrition prescription should work toward gradually increasing weight at the rate of about 0.5 to 1 lb/wk, by increasing energy intake at 100 to 200 kcal increments every few days toward a target of approximately 90% of average body weight for sex, height, and age. Weight gain will not occur until intake exceeds output, and eventual intake for continued weight gain can exceed 3500 kcal/day, especially for patients who are anxious and have high levels of thermogenesis from non-exercise activity. Stabilizing intake is the goal for patients with BN, with a gradual introduction of forbidden foods while also limiting foods that might trigger a binge.

When initiating treatment of an ED in a primary care setting, the clinician should be aware of common cognitive patterns. Patients with AN typically have all-or-none thinking (related to perfectionism) with a tendency to over-generalize and jump to catastrophic conclusions, while assuming that their body is governed by rules that do not apply to others. These tendencies lead to the dichotomization of foods into good or bad categories, having a day ruined because of one unexpected event, or choosing foods based on rigid self-imposed restrictions. These thoughts may be related to neurocircuitry and neurotransmitter abnormalities related to executive function and rewards.

A standard nutritional balance of 15-20% calories from protein, 50-55% from carbohydrate, and 25-30% from fat is appropriate. The fat content may need to be lowered to 15-20% early in the treatment of AN because of continued fat phobia. With the risk of low BMD in patients with AN, calcium and vitamin D supplements are often needed to attain the recommended 1300 mg/day intake of calcium. Refeeding can be accomplished with frequent small meals and snacks consisting of a variety of foods and beverages (with minimal diet or fat-free products), rather than fewer high-volume high-calorie meals. Some patients find it easier to take in part of the additional nutrition as canned supplements (medicine) rather than food. Regardless of the source of energy intake, the risk for refeeding syndrome (acute tachycardia and heart failure with neurologic symptoms associated primarily with acute decline in serum phosphate and magnesium) increases with the degree of weight loss and the rapidity of caloric increases. Therefore, if the weight has fallen below 80% of expected weight for height, refeeding should proceed cautiously, possibly in the hospital (Table 26-7).

Table 26-7 INDICATIONS FOR IN-PATIENT MEDICAL HOSPITALIZATION OF PATIENTS WITH ANOREXIA NERVOSA

PHYSICAL AND LABORATORY

PSYCHIATRIC

MISCELLANEOUS

Patients with AN tend to have a highly structured day with restrictive intake, in contrast to BN, which is characterized by a lack of structure, resulting in chaotic eating patterns and binge-purge episodes. Patients with AN, BN, or ED-NOS all benefit from a daily structure for healthy eating that includes 3 meals and at least 1 snack a day, distributed evenly over the day, based on balanced meal planning. Breakfast deserves special emphasis because it is often the first meal eliminated in AN and is often avoided the morning after a binge-purge episode. In addition to structuring meals and snacks, patients should plan structure in their activities. Although overexercising is common in AN, completely prohibiting exercise can lead to further restriction of intake or to surreptitious exercise; inactivity should be limited to situations in which weight loss is dramatic or there is physiologic instability. Also, healthy exercise (once a day, for no more than 45 minutes, at no more than moderate intensity) can improve mood and make increasing calories more acceptable. Because patients with AN often are unaware of their level of activity and tend toward progressively increasing their output, exercising without either a partner or supervision is not recommended.

Primary Care Treatment

Follow-up primary care visits are essential in the management of EDs; close monitoring of the response of the patient and the family to suggested interventions is required to determine which patients can remain in primary care treatment (patients with early, mildly disordered eating), which patients need to be referred to individual specialists for co-management (mildly progressive disordered eating), and which patients need to be referred for interdisciplinary team management (EDs). Between the initial and subsequent visits, the patient can record daily caloric intake (food, drink, amount, time, location), physical activity (type, duration, intensity), and emotional state (e.g., angry, sad, worried) in a journal that is reviewed jointly with the patient in follow-up. Focusing on the recorded data helps the clinician to identify dietary and activity deficiencies and excesses as well as behavioral and mental health patterns, and the patient to become objectively aware of the relevant issues to address in recovery.

Given the tendency of patients with AN to overestimate their caloric intake and underestimate their activity level, before reviewing the journal record it is important at each visit to measure weight, without underwear, in a hospital gown after voiding; urine specific gravity; temperature; and blood pressure and pulse in supine, sitting, and standing positions as objective data. In addition, a targeted physical examination focused on hypometabolism, cardiovascular stability, and mental status, as well as any related symptoms, should occur at each visit to monitor progress (or regression).

Referral to Mental Health Services

In addition to referral to a registered dietitian, mental health services are an important element of treatment of EDs. Depending on availability and experience, these services can be provided by a psychiatric social worker, psychologist, or psychiatrist, who should team with the primary care provider. Although patients with AN often are prescribed a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) because of depressive symptoms, there is no evidence of efficacy for patients at low weight; food remains the initial treatment of choice to treat depression in AN. SSRIs, very effective in reducing binge-purge behaviors regardless of depression, are considered a standard element of therapy in BN. SSRI dosage in BN, however, may need to increase to an equivalent of more than 60 mg of fluoxetine to maintain effectiveness.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which focuses on restructuring “thinking errors” and establishing adaptive patterns of behavior, is more effective than interpersonal or psychoanalytic approaches. Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), in which distorted thoughts and emotional responses are challenged, analyzed, and replaced with healthier ones, with an emphasis on “mindfulness,” requires adult thinking skills and is useful for older patients with BN. Group therapy can provide much needed support, but it requires a skilled clinician. Combining patients at various levels of recovery who experience variable reinforcement from dysfunctional coping behaviors can be challenging if group therapy patients compete with each other to be “thinner” or take up new behaviors such as vomiting.

The younger the patient, the more intimately the parents need to be involved in therapy. The only treatment approach with evidence-based effectiveness in the treatment of AN in children and adolescents is family-based treatment, exemplified by the Maudsley approach. This 3-phase intensive outpatient model helps parents play a positive role in restoring their child’s eating and weight to normal, then returns control of eating to the child who has demonstrated the ability to maintain healthy weight, and then encourages healthy progression in the other domains of adolescent development. Features of effective family treatment include an agnostic approach in which the cause of the disease is unknown and irrelevant to weight gain, emphasizing that parents are not to blame for EDs; parents being actively nurturing and supportive of their child’s healthy eating while reinforcing limits on dysfunctional habits, rather than an authoritarian food police or complete hands-off approach; and reinforcement of parents as the best resource for recovery for almost all patients, with professionals serving as consultants and advisors to help parents address challenges.

Referral to an Interdisciplinary Eating Disorder Team

The treatment of a child or adolescent diagnosed with an ED is ideally provided by an interdisciplinary team (physician, nurse, dietitian, mental health provider) with expertise treating pediatric patients. Because such teams, often led by specialists in adolescent medicine at medical centers, are not widely available, the primary care provider might need to convene such a team. Adolescent medicine–based programs report encouraging treatment outcomes, possibly related to patients entering earlier into care and the stigma that some patients and parents may associate with psychiatry-based programs. Specialty centers focused on treating EDs are generally based in psychiatry and often have separate tracks for younger and adult patients. The elements of treatment noted earlier (CBT, DBT, and family-based therapy), as well as individual and group treatment should all be available as part of interdisciplinary team treatment. Comprehensive services ideally include intensive outpatient and/or partial hospitalization as well as inpatient treatment. Regardless of the intensity, type, or location of the treatment services, the patient, parents, and primary care provider are essential members of the treatment team. A recurring theme in effective treatment is helping patients and families re-establish connections that are disrupted by the ED.

Inpatient medical treatment of EDs is generally limited to patients with AN, to stabilize and treat life-threatening starvation and to provide supportive mental health services. Inpatient medical care may be required to avoid refeeding syndrome in severely malnourished patients, provide nasogastric tube feeding for patients unable or unwilling to eat, or initiate mental health services, especially family-based treatment, if this has not occurred on an outpatient basis (see Table 26-7). Admission to a general pediatric or hospital unit is advised only for short-term stabilization in preparation for transfer to a medical unit with expertise in treating pediatric EDs. Inpatient psychiatric care of EDs should be provided on a unit with expertise in managing the often challenging behaviors (e.g., hiding or discarding food, vomiting, surreptitious exercise) and emotional problems (e.g., depression, anxiety). Suicidal risk is small, but patients with AN might threaten suicide if made to eat or gain weight in an effort to get their parents to back off.

An ED partial hospital program (PHP) offers outpatient services that are less intensive than round-the-clock inpatient care. Generally held 4 to 5 days a week for 6 to 9 hours each session, PHP services typically are group-based and include eating at least two meals as well as opportunities to address issues in a setting that more closely approximates “real life” than inpatient treatment. That is, patients sleep at home and are free-living on weekends, exposing them to challenges that can be processed during the 25 to 40 hours in program, also sharing group and family experiences.

Supportive Care

In relation to pediatric EDs, support groups are primarily designed for parents. Because their daughter or son with an ED often resists the diagnosis and treatment, parents often feel helpless and hopeless. Because of the historical precedent of blaming parents for causing EDs, parents often express feelings of shame and isolation (www.maudsleyparents.org). Support groups and multifamily therapy sessions bring parents together with other parents whose families are at various stages of recovery from an ED in ways that are educational and encouraging. Patients often benefit from support groups after intensive treatment or at the end of treatment because of residual body image or other issues after eating and weight have normalized.

Prognosis

With early diagnosis and effective treatment, 80% or more of youth with AN recover: They develop normal eating and weight control habits, resume menses, maintain average weight for height, and function in school, work, and relationships, although some still have poor body image. With weight restored to normal, fertility returns as well, although the weight for resumption of menses (about 92% of average body weight for height) may be lower than the weight for ovulation. The prognosis for BN is less well established, but outcome improves with multidimensional treatment that includes SSRIs and attention to mood, past trauma, impulsivity, and any existing psychopathology. Even less is known about the prognosis for ED-NOS.

Prevention

Given the complexity of the pathogenesis of EDs, prevention is difficult. Targeted preventive interventions can reduce risk factors in older adolescents and college-age women. Universal prevention efforts to promote healthy weight regulation and discourage unhealthy dieting have not shown effectiveness in middle-school students. Programs that include recovered patients or focus on the problems associated with EDs can inadvertently normalize or even glamorize EDs and should be discouraged.

American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders, ed 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

Culbert KM, Slane JD, Klump KL. Genetics of eating disorders. In: Wonderlich S, Mitchell J, de Zwann M, et al, editors. Annual review of eating disorders part 3. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing; 2008:27-42.

Fassino S, Amianto F, Abbate-Daga G. The dynamic relationship of parental personality traits with the personality and psychopathology traits of anorectic and bulimic daughters. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):232-239.

Favaro A, Monteleone P, Santonastaso P, et al. Psychobiology of eating disorders. In: Wonderlich S, Mitchell J, de Zwann M, et al, editors. Annual review of eating disorders part 2. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing, 2008.

Jones M, Luce KH, Osbourne MI, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an Internet-facilitated intervention for reducing binge eating and overweight in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121:453-462.

Katzman D. Medical complications in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:S52-S59.

Kaye WH, Fudge JL, Paulus M. New insights into symptoms and neurocircuit function of anorexia nervosa. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(8):573-584.

Keel PK, Gravener JA. Sociocultural influences on eating disorders. In: Wonderlich S, Mitchell J, de Zwann M, et al, editors. Annual review of eating disorders part 2. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing, 2008.

Keel PK, Wolfe BE, Liddle RA, et al. Clinical features and physiological response to a test meal in purging disorder and bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1038-1056.

Le Grange D, Crosby RD, Rathouz PJ, et al. A randomized controlled comparison of family-based treatment and supportive psychotherapy for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1049-1056.

Neumark-Sztainer D. Preventing obesity and eating disorders in adolescents: what can health care providers do? J Adolesc Health. 2009;44(3):206-213.

Rome ES, Ammerman S, Rosen DS, et al. Children and adolescents with eating disorders: the state of the art. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):e98-e108.

Schienle A, Schafer A, Hermann A, et al. Binge-eating disorder: reward sensitivity and brain activation to images of food. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:654-661.

Treasure J, DesForges J. Neuroimaging. In: Wonderlich S, Mitchell J, de Zwann M, et al, editors. Annual review of eating disorders part 2. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing, 2008.