Chapter 38 Failure to Thrive

Failure to thrive (FTT) is the result of inadequate usable calories necessary for a child’s metabolic and growth demands, and it manifests as physical growth that is significantly less than that of peers. No one set of growth parameters provides the criteria for a universal definition of FTT, although the pattern may be helpful (Fig. 38-1). FTT has classically been grouped into organic and nonorganic causes, but FTT is better defined as the end result of inadequate usable calories with contributing risk factors from multiple categories.

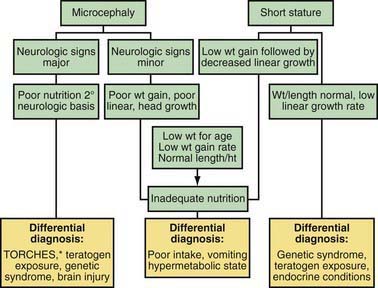

Figure 38-1 Approach to the differential diagnosis of failure to thrive. *See key to Table 38-1.

(Derived from Gahagan S: Failure to thrive: a consequence of undernutrition, Pediatr Rev 27:e1–e11, 2006.)

Epidemiology

The prevalence of FTT depends on the risks within populations. In developing countries or countries torn by conflict, infectious diseases, and inadequate nutrition are the primary risks. In developed countries, the primary risks are preterm birth and family dysfunction. In all settings there are a myriad of other causes (Table 38-1).

Table 38-1 FAILURE TO THRIVE: DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS BY SYSTEM

PSYCHOSOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL

NEUROLOGIC

RENAL

ENDOCRINE

GENETIC/METABOLIC/CONGENITAL

GASTROINTESTINAL

CARDIAC

PULMONARY/RESPIRATORY

MISCELLANEOUS

INFECTIONS

* CHARGE, coloboma, heart disease, atresia choanae, retarded growth and retarded development and/or central nervous system anomalies, genital hypoplasia, and ear anomalies and/or deafness; TORCHES, toxoplasma, other, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex; VATER, vertebral defects, imperforate anus, tracheoesophageal fistula, and radial and renal dysplasia.

Clinical Manifestations

The most common clinical presentation of FTT is poor growth, which is depicted using standardized growth charts. Poor growth may be accompanied by physical signs such as alopecia, reduced subcutaneous fat or muscle mass, and dermatitis. Syndromes of marasmus or kwashiorkor are more common in developing countries (Chapter 43).

Weight for corrected age, weight for height, body mass index, and failure to gain adequate weight over a period of time help define FTT (Chapter 13). Growth parameters should be measured serially and plotted on growth charts appropriate for the child’s sex, age, and, if preterm, postconceptual age. Growth charts are also available for some known chromosomal abnormalities, such as Down syndrome or Turner syndrome.

Etiology and Diagnosis

The causes of insufficient growth include (1) failure of a caregiver to offer adequate calories, (2) failure of the child to take in sufficient calories, (3) failure of the child to retain and use sufficient calories, and (4) increased metabolic demands. History, physical examination, and observation of the parent-child interaction in the clinical or home environment usually suggest the most likely etiologies and thus direct appropriate workup and management (see Fig. 38-1). A complete history should include a detailed nutritional, family, and prenatal history; documentation of who feeds and cares for the child; further information regarding the timing of the growth failure; and a thorough review of systems. In young infants it is important to obtain a detailed dietary history, including quantity, quality, and frequency of meals, in addition to information about the caregiver’s response to excessive crying or sleeping.

The causes of FTT are numerous, involving every organ system (see Table 38-1). The clinician may approach the diagnosis in terms of age (Table 38-2) or signs and symptoms (Table 38-3). The timing of the growth deficiency can indicate a cause, such as the introduction of gluten into the diet of a child with celiac disease or a coincidental psychosocial event. Regardless of gestational age, a chromosomal abnormality, intrauterine infection, or teratogen exposure should be considered in a child with symmetric growth failure since birth.

Table 38-3 APPROACH OF FAILURE TO THRIVE BASED ON SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

| HISTORY/PHYSICAL EXAMINATION | DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATION |

|---|---|

| Spitting, vomiting, food refusal | Gastroesophageal reflux, chronic tonsillitis, food allergies |

| Diarrhea, fatty stools | Malabsorption, intestinal parasites, milk protein intolerance |

| Snoring, mouth breathing, enlarged tonsils | Adenoid hypertrophy, obstructive sleep apnea |

| Recurrent wheezing, pulmonary infections | Asthma, aspiration, food allergy |

| Recurrent infections | HIV or congenital immunodeficiency diseases |

| Travel to/from developing countries | Parasitic or bacterial infections of the gastrointestinal tract |

The physical examination should focus on identifying chronic illnesses, recognizing syndromes that may alter growth, and documenting the effects of malnutrition (Table 38-4).

Table 38-4 APPROACH TO PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

| Vital signs | Blood pressure, temperature, pulse respirations, anthropometry |

| General appearance | Activity, affect, posture |

| Skin | Hygiene, rashes, neurocutaneous markings, signs of trauma (bruises, burns, scars) |

| Head | Hair whorls, quality of hair, alopecia, fontanel size, frontal bossing, sutures, shape, dysmorphisms, philtrum |

| Eyes | Ptosis, strabismus, palpebral fissures, conjunctival pallor, fundoscopic exam |

| Ears | External form, rotation, tympanic membranes |

| Mouth, nose, throat | Thinness of lip, hydration, dental health, glossitis, cheilosis, gum bleeding |

| Neck | Hairline, masses, lymphadenopathy |

| Abdomen | Protuberance, hepatosplenomegaly, masses |

| Genitalia | Malformations, hygiene, trauma |

| Rectum | Fissures, trauma, hemorrhoids |

| Extremities | Edema, dysmorphisms, rachitic changes, nails |

| Neurologic | Cranial nerves, reflexes, tone, retention of primitive reflexes, voluntary movement |

Adapted from American Academy of Pediatrics: Failure to thrive. In Kleinman RE, editor: Pediatric nutrition handbook, ed 6, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2009, American Academy of Pediatrics, pp 601–636.

The laboratory evaluation of children with FTT should be judicious and based on findings from the history and physical (see Fig. 38-1). Obtaining the state’s newborn screening results, a complete blood count, and urinalysis represent a reasonable initial screen.

A minority of children with FTT will be solely categorized as child neglect (Chapter 37). Risk factors for neglect are often shared by those with FTT, such as poverty, social isolation, and caregiver mental health issues.

Treatment

Treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach, understanding all the elements that contribute to a child’s growth: a child’s health and nutritional status, family issues, and the parent-child interaction. An appropriate feeding atmosphere at home is important for all children with FTT.

Indications for hospitalization include severe malnutrition or failure of outpatient management. If a child without other conditions requiring hospitalization has not responded after 2-3 mo of outpatient management, then a specialized, multidisciplinary inpatient assessment should be considered. Inpatient care may include further diagnostic and laboratory evaluation, an assessment and implementation of adequate nutrition, and further evaluation of the parent-child feeding interaction.

Children with severe malnutrition must be re-fed carefully with an incremental increase in calories to avoid re-feeding syndrome (Chapter 43). The type of caloric supplementation is based on the severity of FTT and the underlying medical condition. The response to feeding depends on the specific diagnosis, medical treatment, and severity of FTT. Minimal catch-up growth should generally be 2-3 times the average weight gain for corrected age. Multivitamin supplementation should be given to all children with FTT to meet the recommended dietary allowance, because these children commonly have iron, zinc, and vitamin D deficiencies, as well as increased micronutrient demands with catch-up growth.

Prognosis

FTT in the first year of life, regardless of cause, is particularly ominous. Maximal postnatal brain growth occurs in the first 6 mo of life. The prognosis for children with FTT is variable, depending on the specific diagnosis and severity of FTT. Children with early FTT are at higher risk for short stature, and behavioral and academic difficulties. Community-based studies of children with a history of FTT have found IQ scores to be about 4 points lower than children with a history of adequate growth. Appropriate assessment and intervention of cognitive and emotional development is necessary for all children with FTT. Referrals to early intervention, Head Start, or Supplemental Security Income (SSI) may be beneficial. Home intervention may attenuate some of these negative effects of early failure to thrive.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Failure to thrive. In: Kleinman RE, editor. Pediatric nutrition handbook. ed 6. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:601-636.

Black MM, Dubowitz H, Krishnakumar A, et al. Early intervention and recovery among children with failure to thrive: follow-up at 8 years. Pediatrics. 2007;120:59-69.

Block RW, Krebs NF, et al. Failure to thrive as a manifestation of child neglect. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1234-1237.

Bonuck K, Parikh S, Bassila M. Growth failure and sleep disordered breathing: a review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:769-778.

Daniel M, Kleis L, Cemeroglu AP. Etiology of failure to thrive in infants and toddlers referred to a pediatric endocrinology outpatient clinic. Clin Pediatr. 2008;47:762-765.

Emond AM, Blair PS, Emmett PM, et al. Weight faltering in infancy and IQ levels at 8 years in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1051-e1058.

Gahagan S. Failure to thrive: a consequence of undernutrition. Pediatr Rev. 2006;27:e1-e11.

Olsen EM. Failure to thrive: still a problem of definition. Clin Pediatr. 2006;45:1-6.