Chapter 59 Herbs, Complementary Therapies, and Integrative Medicine

Integrative medicine focuses on promoting health to achieve physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, and social well-being in the context of a medical home in a healthy community. The foundations of integrative medicine are health-promoting practices including optimal nutrition, dietary supplements to avoid deficiencies, physical activity, adequate sleep, a healthy environment, stress management, and supportive social relationships. Other complementary therapies recommended by some integrative practitioners include herbal remedies, massage and other forms of bodywork, and acupuncture. Although prayer, healing touch, and healing rituals are sometimes included under the rubric of complementary and integrative therapies, they are not covered in this chapter.

Dietary Supplements

Herbs and other dietary supplements are the most commonly used complementary therapies for children and adolescents. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines dietary supplements as oral preparations that may include vitamins, minerals, single or multiple herbal ingredients, amino acids, essential fatty acids, hormones (such as melatonin and DHEA), and probiotics. More than $4 billion are spent on these products each year in the USA. Some uses are common and recommended, such as vitamin D supplements for breast-fed infants, whereas other uses are more controversial, such as using echinacea to treat upper respiratory infections. Use of dietary supplements is most common among children whose families have higher income and education and whose parents use them, and among older children and those suffering from chronic, incurable, or recurrent conditions. Less than 50% of patients who use supplements talk with their physician about their use. Even when asked directly, some patients deny using herbs (such as coffee, cranberry, protein powders, probiotics, or fish oil) because they do not consider their use to be medicinal and they consider them to be safe because they are “natural.” To elicit a complete history, clinicians need to ask patients routinely about and provide examples of dietary supplements.

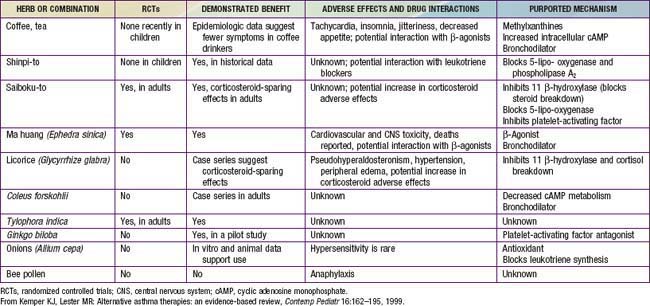

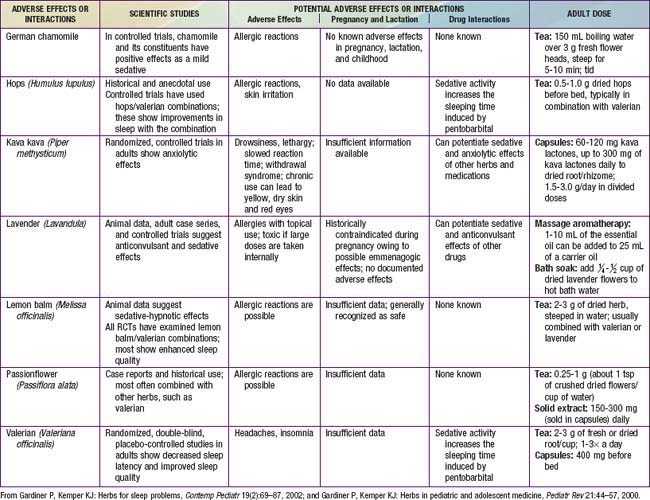

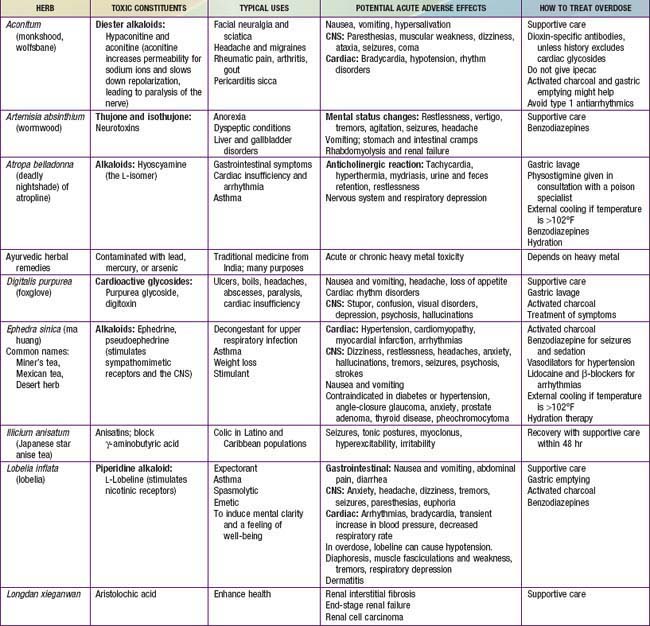

Although they are generally safe, natural products can cause serious toxicity (Tables 59-1 to 59-5). For example, acute hepatic toxicity and death can result from ingestion of even small amounts of Amanita mushrooms. Ephedra, also known as ma huang, is banned as a weight loss or sports supplement in the United States because of its toxicity. Even when a product is safe when used correctly, it can cause mild or severe toxicity when used incorrectly. For example, although peppermint is a commonly used and usually benign gastrointestinal spasmolytic included in after-dinner mints, it can exacerbate gastroesophageal reflux. Probiotics are generally safe when taken orally, but in an immune-compromised patient in an ICU setting, they can cause sepsis. Excessive vitamin C or magnesium can cause diarrhea.

Table 59-3 HERBS FOR SKIN CONDITIONS

| ACTION | HERB OR SUPPLEMENT FOR TOPICAL USE |

|---|---|

| Soothing, emollient | Aloe, calendula |

| Anti-inflammatory | Aloe, chamomile, evening primrose oil, lemon balm |

| Antiviral | Aloe vera, calendula, chamomile, lemon balm |

| Antibacterial | Aloe vera, calendula, chamomile, lavender, lemon balm, tea tree oil |

| Antifungal | Lavender, tea tree oil |

From Gardiner P, Coles D, Kemper KJ: The skinny on herbal remedies for dermatologic disorders, Contemp Pediatr 18:103–104, 107–110, 112–114, 2001.

Table 59-5 SPANISH-ENGLISH BOTANICAL NAME TRANSLATION CHART*

| SPANISH NAME | ENGLISH NAME | BOTANICAL NAME |

|---|---|---|

| Ajo | Garlic | Allium sativum |

| Azarcon | Lead tetraoxide | Not a plant |

| Azogue | Mercury | Not a plant |

| Cebolla | Onion | Allium cepa |

| Cenela | Cinnamon | Cinnamomum aromaticum |

| Clavo | Cloves | Eugenia aromatica |

| Comino | Cumin | Cuminum cyminum |

| Epasote or herba Sancti Mariae | Wormseed | Chenopodium anthelminticum |

| Estafiate | Wormwood | Artemisia absinthium |

| Eucalipto | Eucalyptus | Eucalyptus globulus |

| Granada | Pomegranate | Punica granatum |

| Jengibre | Ginger | Zingiber officinale |

| Limon | Lemon | Citrus limon |

| Manzanilla | Chamomile | Anthemis nobilis or Chamomilla recutita or Matricaria chamomilla |

| Oregano | Oregano | Origanum vulgare |

| Pelos de elote | Corn silk | Zea mays |

| Savila | Aloe vera | Aloe vera |

| Siete jarabes | Mixture of syrup of sweet almond, castor oil, balsam resin, wild cherry, licorice, cocillana bark, honey | |

| Tomillo | Thyme | Thymus vulgaris |

| Una de gato | Cat’s claw | Uncaria tomentosa |

| Valeriana | Valerian | Valeriana officinalis |

| Yerba buena | Spearmint | Mentha spicata |

* Prepared with assistance of Laura Howell, MD.

Product labels might not accurately reflect the contents or the concentrations of ingredients. Because of natural variability, variations of 10- to 1,000-fold have been reported for several popular herbs, even across lots produced by the same manufacturer. Herbal products may be unintentionally contaminated with pesticides, animal wastes, or the wrong herb that was misidentified during harvesting. Some DHEA supplements have been found to contain banned stimulants and steroids. Products from developing countries (e.g., ayurvedic products from South Asia) might contain toxic levels of mercury, cadmium, arsenic, or lead, either from unintentional contamination during manufacturing or from intentional additions by producers who believe that these metals have therapeutic value. Approximately 30-40% of Asian patent medicines include potent pharmaceuticals, such as analgesics, antibiotics, hypoglycemic agents, or corticosteroids; typically, the labels for these products are not written in English and do not note the inclusion of pharmaceutical agents. Even mineral supplements, such as calcium, have been contaminated with lead or had significant problems with product variability.

Many families use supplements concurrently with medications, posing hazards of interactions. For example, St. John’s wort induces CYP3A4 activity of the P450 enzyme system and thus can enhance elimination of digoxin, cyclosporine, protease inhibitors, oral contraceptives, and numerous antibiotics, leading to subtherapeutic serum levels. It can also increase the risk of serotonin syndrome in patients taking antidepressant medications.

In the USA, dietary supplements do not undergo the same stringent evidence-based evaluation and post-marketing surveillance as prescription medications. Although they may not claim to prevent or treat specific medical conditions, product labels may make “structure-function” claims. A label may claim that a product “promotes a healthy immune system,” but it may not claim to cure the common cold. The FDA can only restrict sales of certain products after receiving reports of adverse effects. Adverse reactions should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program; failure to do so limits the FDA’s ability to monitor and manage the clinical and public health risks of these products.

Evidence about the effectiveness of dietary supplements to prevent or treat pediatric problems is mixed, depending on the product used and condition treated; research in this area is growing rapidly. Some herbal products may be helpful adjunctive treatments for common childhood problems. For example, some herbs have proved helpful for colic (fennel and the combination of chamomile, fennel, vervain, licorice, balm mint), nausea (ginger), irritable bowel syndrome (peppermint), and diarrhea (probiotics) (Chapter 332).

Massage and Other Bodywork Therapies

Massage is commonly provided at home by parents and by licensed massage therapists and nurses in clinical settings. Infant massage is routinely provided in many neonatal intensive care units to promote growth and development in preterm infants. Massage also has been demonstrated to be beneficial for pediatric patients suffering from asthma, insomnia, colic, cystic fibrosis, and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Massage therapy is generally safe.

Chiropractic is one of the most common professionally provided complementary practices. More than 50,000 chiropractors are licensed in the United States, and up to 14% of all chiropractic visits are for pediatric patients. Few randomized, controlled trials have demonstrated significant clinical benefits of chiropractic for pediatric patients; parents need to be cautioned not to rely on chiropractic as the primary treatment for serious conditions, such as cancer. Although anecdotal data suggest that severe complications are possible with chiropractic treatment of infants and children, such adverse effects appear to be rare. Further controlled trials are needed to determine the costs, benefits, and safety of chiropractic.

Acupuncture

Modern acupuncture incorporates treatment traditions from China, Japan, Korea, France, and other countries. The technique that has undergone most scientific study involves penetrating the skin with thin, solid, metallic needles that are manipulated by hand or by electrical stimulation. Variants of needle therapy include stimulation of acupuncture points by rubbing (shiatsu), heat (moxibustion), lasers, magnets, pressure (acupressure), or electrical currents.

Acupuncture is used by an increasing number of pediatric patients. Although most pediatric patients are averse to needles, patients who suffer from severe chronic pain may be amenable to trying acupuncture and often report that it is helpful. Acupuncture services are offered by more than  of North American academic pediatric pain treatment programs. Although additional studies are needed in children, research in adults suggests that acupuncture can offer significant benefits in the treatment of recurrent headache, depression, and nausea. As with any therapy involving needles, infections and bleeding are expected, but uncommon complications and more serious complications, such as pneumothorax, occur in <1 in 30,000 treatments.

of North American academic pediatric pain treatment programs. Although additional studies are needed in children, research in adults suggests that acupuncture can offer significant benefits in the treatment of recurrent headache, depression, and nausea. As with any therapy involving needles, infections and bleeding are expected, but uncommon complications and more serious complications, such as pneumothorax, occur in <1 in 30,000 treatments.

Ball SD, Kertesz D, Moyer-Mileur LJ. Dietary supplement use is prevalent among children with a chronic illness. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:78-84.

Beider S, Mahrer NE, Gold JI. Pediatric massage therapy: an overview for clinicians. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:1025-1041.

Gardiner P, Phillips RS, Kemper KJ, et al. Dietary supplements: inpatient policies in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e775-e781.

Goldman RD, Rogovik AL, Lai D, et al. Potential interactions of drug–natural health products and natural health products–natural health products among children. J Pediatr. 2008;152:521-526.

Kemper KJ, Vohra S, Walls R. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in pediatrics. Task Force on Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Provisional Section on Complementary, Holistic, and Integrative Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1374-1386.

Lin YC, Lee AC, Kemper KJ, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in pediatric pain management service: a survey. Pain Med. 2005;6:452-458.

Sadler C, Vanderjagt L, Vohra S. Complementary, holistic, and integrative medicine: butterbur. Pediatr Rev. 2007;28:235-238.

Shamseer L, Vohra S. Complementary, holistic, and integrative medicine: cranberry. Pediatr Rev. 2007;28:e43-e45.

Vohra S, Johnston BC, Cramer K, et al. Adverse events associated with pediatric spinal manipulation: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e275-e283.