Chapter 150 Ankylosing Spondylitis and Other Spondyloarthritides

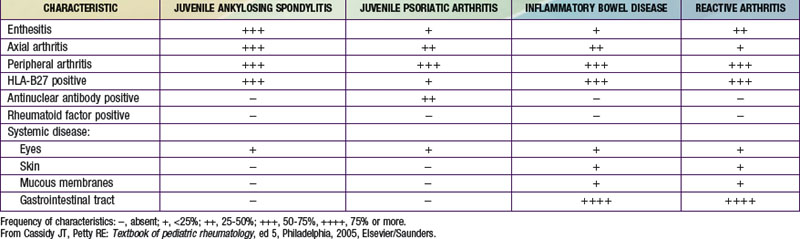

The diseases collectively referred to as spondyloarthritides include ankylosing spondylitis (AS), arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and psoriasis, and reactive arthritis following gastrointestinal or genitourinary infections (see Table 150-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website![]() at www.expertconsult.com). Pediatric rheumatologists have adopted the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) classification scheme for juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and use the term enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) to encompass most forms of spondyloarthritis in children, except those with co-existing psoriasis.

at www.expertconsult.com). Pediatric rheumatologists have adopted the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) classification scheme for juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and use the term enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) to encompass most forms of spondyloarthritis in children, except those with co-existing psoriasis.

Epidemiology

ERA constitutes about 10% of JIA, which is estimated to occur in about 0.4% of children. AS occurs in 0.2-0.5% of adults, with approximately 15% of cases beginning in childhood (juvenile-onset AS, or JAS). Unlike other forms of JIA, spondyloarthritis is most common in older boys. These disorders are often familial, owing in large part to the influence of HLA-B27. This HLA allele is found in >90% of AS/JAS, compared with <10% of healthy individuals. It is also more common in patients with other forms of spondyloarthritis, particularly when there is inflammation of the axial skeleton.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Spondyloarthritides are complex genetic diseases in which susceptibility is largely genetically determined. HLA-B27 is responsible for around 40% of AS susceptibility, with genes encoding the interleukin-23 (IL-23) receptor (IL23R), ERAP1 (endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase-1; also known as ARTS-1 [type 1 tumor necrosis factor receptor shedding aminopeptidase regulator]), IL-1α (IL1A), and others playing important roles. Enteric infection with certain gastrointestinal or genital pathogens can trigger reactive arthritis (Chapter 151); environmental triggers for other forms of spondyloarthritis have not been identified. Although molecular mimicry between HLA-B27 and antigens from bacteria has been postulated as an underlying mechanism of disease, evidence supporting this hypothesis is scarce. Other unusual properties of HLA-B27, such as its tendency to misfold and form unusual cell surface structures, may play a role.

Inflamed joints in spondyloarthritides contain T cells, B cells, macrophages, proliferating fibroblasts, and neovascularization of the synovium. Enthesitis, a key feature of the spondyloarthritides, is marked by inflammation where tendons, ligaments, and joint capsules attach to bone. Enthesitis lesions also exhibit chronic inflammation, resulting in calcification of ligaments and fusion of joints in advanced disease such as AS.

Clinical Manifestations

Axial and peripheral joint inflammation and enthesitis cause pain and swelling, localized tenderness, stiffness, and loss of range of motion. Common extra-articular manifestations include gastrointestinal inflammation even in the absence of overt IBD and ocular inflammation, which causes pain, erythema, and photophobia.

Enthesitis-Related Arthritis

Children are classified as having ERA if they have either arthritis and enthesitis or arthritis or enthesitis, with two of the following additional characteristics: (1) sacroiliac joint tenderness or inflammatory lumbosacral pain (see Table 150-1), (2) the presence of HLA-B27, (3) age > 6 yr and male sex, (4) acute anterior uveitis, and (5) a family history of an HLA-B27–associated disease (ERA, sacroiliitis with IBD, reactive arthritis, or acute anterior uveitis) in a first-degree relative. Patients with psoriasis (or a family history of psoriasis in a first-degree relative), a positive rheumatoid factor (RF) test result, or systemic arthritis are excluded from this group. Many children with ERA go on to eventually have AS, but many do not, and it is not currently possible to determine whose ERA will progress.

Juvenile Ankylosing Spondylitis

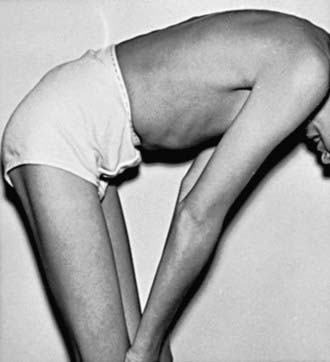

JAS frequently begins with oligoarthritis and enthesitis. The arthritis occurs predominantly in the lower extremities and often involves the hips, in contrast to oligoarticular JIA. Also unlike in adult-onset AS, in JAS axial involvement is usually absent until later in the disease course (Fig. 150-1). Enthesitis is particularly common, manifesting as localized and often severe tenderness at characteristic tendon (as well as ligament, fascia or capsule) insertions around the plantar surface of the foot, ankle (Achilles), and knee (patella). The disease course is variable and can include periods of low disease activity. Fever and weight loss are uncommon and, if present, raise the possibility of IBD.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is equally common in girls and boys, and arthritis can precede psoriasis. The most common presentation is asymmetric arthritis involving < 5 joints. Both large (knee, ankle) and small (finger, toe) joints can be involved, including distal interphalangeal joints. The presence of HLA-B27 is not a risk factor for psoriasis, and most patients with psoriatic arthritis do not have axial involvement. However, when HLA-B27 is present, axial arthritis is more common. In a child with oligoarthritis or even polyarthritis, the presence of nail pitting (Fig. 150-2), dactylitis, onycholysis, and/or a family history of psoriasis supports the diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis.

Arthritis with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Two patterns of arthritis complicate IBD. Polyarthritis affecting large and small joints is most common and often reflects the activity of the intestinal inflammation. Less frequently, arthritis of the axial skeleton including the sacroiliac joints occurs, resulting in AS. As with psoriatic arthritis, the presence of HLA-B27 is a risk factor for the development of axial disease. The severity of axial involvement is independent of the activity of the gastrointestinal inflammation.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory evidence of systemic inflammation with elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and/or C-reactive protein value is variable in most spondyloarthritides and may or may not be present at the onset of disease. RF and antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) are absent, except in patients with psoriatic arthritis, of which as many as 50% are ANA positive. HLA-B27 is present in >90% of children with JAS, compared with ≈ 7% of healthy individuals, but is less frequent in ERA and other types of spondyloarthritis.

Early radiographic changes in the sacroiliac joints include indistinct margins and erosions, with sclerosis typically starting on the iliac side of the joint (Fig. 150-3). Peripheral joints may exhibit periarticular osteoporosis, with loss of sharp cortical margins in areas of enthesitis, which may eventually show erosions or bony spurs. Squaring of the corners of the vertebral bodies and the classic “bamboo spine,” with syndesmophyte formation and calcification of ligaments characteristic of advanced AS, develop later. These findings are rare in early disease, particularly in childhood.

Diagnosis

Spondyloarthritis is suggested by the onset of oligoarthritis and/or enthesitis in an older boy. The arthritis predominantly affects hips, knees, ankles, and feet (often the intertarsal joints). When the axial skeleton is involved, patients may experience inflammatory back pain, which is characterized by nighttime pain and considerable morning stiffness that is improved by activity and worsened by rest (Table 150-2). With progressive disease there is a loss of the normal lumbar lordosis, inability to touch the toes with the legs straight, and sacroiliac pain on palpation or with pelvic compression. AS is diagnosed if there is sufficient radiographic evidence of sacroiliitis and the patient meets at least one clinical criterion involving inflammatory back pain, limitation of motion in the lumbar spine, or limitation of chest expansion. JAS is present if the patient is <16 yr. The term juvenile-onset AS is frequently used to describe AS when the symptoms begin before age 16 yr but full criteria for a diagnosis are not met. Because radiographic evidence of sacroiliitis can take 10 yr or longer to develop and clinical manifestations may be subtle, it can be difficult to differentiate spondyloarthritis from JIA early in the disease course. Efforts to establish criteria that are more sensitive for diagnosing axial spondyloarthritis with MRI and use of other clinical features and markers are underway.

In a child with chronic arthritis, the presence of erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, fever, weight loss, or anorexia suggests IBD. The onset of arthritis following a recent history of diarrhea, and symptoms of urethritis or conjunctivitis may suggest reactive arthritis. Psoriasis, nail changes (see Fig. 150-2), or a family history of psoriasis suggests psoriatic arthritis. Early differentiation between the various forms of spondyloarthritis by laboratory or radiographic means is difficult. Sacroiliac joint involvement or enthesitis, including adjacent bone marrow edema, may be seen on MRI, and results of a technetium Tc 99m bone scan may be positive, but results of the latter examination are often difficult to interpret in children and adolescents.

Differential Diagnosis

Lower back pain can be caused by suppurative arthritis of the sacroiliac joint, osteomyelitis of the pelvis or spine, osteoid osteoma of the posterior elements of the spine, pelvic muscle pyomyositis, or malignancies. In addition, mechanical conditions such as spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and Scheuermann disease should be considered. Back pain secondary to fibromyalgia usually affects the soft tissues of the upper back in a symmetric pattern and is associated with well-localized tender points (Chapter 671.5).

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (avascular necrosis of the femoral head), slipped capital femoral epiphysis, and chondrolysis may also manifest as pain over the inguinal ligament and loss of internal rotation of the hip joint, but without other features of spondyloarthritis, such as involvement of other entheses and/or joints. Radiography or MRI is critical for distinguishing these conditions.

Treatment

The aims of therapy for JAS are to control inflammation, minimize pain, preserve function, and prevent ankylosis (fusion of adjacent bones) using a combination of anti-inflammatory medications, physical therapy, and education. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as naproxen (15-20 mg/kg/day), are frequently used initially and may reduce bony progression if used continually. With relatively mild disease such as might be present in ERA, NSAIDs can be helpful when used along with intra-articular corticosteroids (e.g., triamcinolone hexacetonide) to control peripheral joint inflammation. However, for JAS, it is typically necessary to add a second-line agent. Sulfasalazine (up to 50 mg/kg/day; maximum 3 gm/day) or methotrexate (10 mg/m2) may be beneficial for peripheral arthritis, but these medications have not been shown to improve axial disease in adults. Biologics that inhibit tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab) have been efficacious in reducing symptoms and improving function in adults with AS, and there is evidence that similar responses are seen in children. TNF inhibitors have not been shown to halt bony progression in established AS, underscoring the need for earlier recognition and better therapies.

Physical therapy and low-impact exercise should be included in the treatment program for all children with spondyloarthritis. Exercise to maintain range of motion in the back, thorax, and affected joints should be instituted early in the disease course. Custom-fitted insoles are particularly useful in management of painful entheses around the feet, and the use of pillows to position the lower extremities while the child is in bed can be helpful.

Prognosis and Complications

There are few outcome studies in juvenile spondyloarthritis. Important questions, such as which patients with ERA will go on to have JAS/AS, have yet to be addressed. In one follow-up study as many as 60% of adults with undifferentiated spondyloarthritis progressed to having AS after 10 yr. Outcomes for JAS compared with adult-onset AS suggest that hip disease requiring replacement is more common in children but axial disease is more severe in adults. Involvement of the midfoot may portend a poorer prognosis. Reactive arthritis may be brief (several weeks or months) but may become chronic and progress to AS.

Acute anterior uveitis occurs in as many as 25% of patients with JAS. Chronic iridocyclitis similar to that in oligoarticular or polyarticular JIA occurs in approximately 15% of children with psoriatic arthritis but is uncommon in JAS. Aortic valve insufficiency is an uncommon but important complication of AS.

Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet. 2007;369:1379-1390.

Gensler L, Ward MM, Reveille JD, et al. Clinical, radiographic and functional differences between juvenile-onset and adult-onset spondylitis: results from the PSOAS (Prospecitive Study of AS Outcomes) Cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:233-237.

Hofer M. Spondyloarthropathies in children—are they different from those in adults? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20:315-328.

Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767-778.

Sacks J, Helmick C, Yao-Hua L, et al. Prevalence of and annual ambulatory health care visits for pediatric arthritis and other rheumatologic conditions in the US in 2001–2004. Arth Rheum. 2007;57:1439-1445.

Smith JA, Marker-Hermann E, Colbert RA. Pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis: current concepts. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20:571-591.

Tse SML, Burgos-Vargas R, Laxer RM. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-α blockade in the treatment of juvenile spondyloarthropathy. Arth Rheum. 2005;52:2103-2108.