Chapter 162 Musculoskeletal Pain Syndromes

Musculoskeletal pain is a frequent complaint of children presenting to general pediatricians and is the most common presenting problem of children referred to pediatric rheumatology clinics. Prevalence estimates of persistent musculoskeletal pain in community samples range from roughly 10% to 30%. Although diseases such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) may manifest as persistent musculoskeletal pain, the majority of musculoskeletal pain complaints in children are benign in nature and attributable to trauma, overuse, and normal variations in skeletal growth. There is a subset of children in whom chronic pain complaints develop that persist in the absence of physical and laboratory abnormalities. Children with idiopathic musculoskeletal pain syndromes also typically have marked subjective distress and functional impairment. The treatment of children with musculoskeletal pain syndromes optimally includes both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions.

Clinical Manifestations

All chronic musculoskeletal pain syndromes involve pain complaints of at least 3 mo in duration in the absence of objective abnormalities on physical examination and laboratory screening. Additionally, children and adolescents with musculoskeletal pain syndromes often complain of persistent pain despite previous treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesic agents. The location varies, with pain complaints either localized to a single extremity or more diffuse and involving multiple extremities. The prevalence of musculoskeletal pain syndromes increases with age and is higher in females, thus rendering adolescent girls at highest risk.

The pain complaints of children and adolescents with musculoskeletal pain syndromes are commonly accompanied by psychologic distress, sleep difficulties, and functional impairment throughout home, school, and peer domains. Psychologic distress can include symptoms of anxiety and depression, such as frequent crying spells, fatigue, sleep disturbance, feelings of worthlessness, poor concentration, and frequent worry. Indeed, a substantial number of children with musculoskeletal pain syndromes display the full range of psychologic symptoms, warranting an additional diagnosis of a comorbid mood or anxiety disorder (e.g., major depressive episode, generalized anxiety disorder). Sleep disturbance in children with musculoskeletal pain syndromes may include difficulty falling asleep, multiple night awakenings, disrupted sleep-wake cycles with increased daytime sleeping, nonrestorative sleep, and fatigue.

For children and adolescents with musculoskeletal pain syndromes, the constellation of pain, psychologic distress, and sleep disturbance often leads to a high degree of functional impairment. Poor school attendance is common, and children may struggle to complete other daily activities relating to self-care and participation in household chores. Peer relationships may also be disrupted because of decreased opportunities for social interaction due to pain. Therefore, children and adolescents with musculoskeletal pain syndromes often report loneliness and social isolation, characterized by having few friends and lack of participation in extracurricular activities.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a musculoskeletal pain syndrome is typically one of exclusion when careful, repeated physical examinations and laboratory testing do not reveal an etiology. At initial presentation, all children with pain complaints require a thorough clinical history and a complete physical examination to look for an obvious etiology (e.g., sprains, strains, or fractures), characteristics of the pain (localized or diffuse), and evidence of systemic involvement. A comprehensive history can be particularly useful in providing clues to the possibility of underlying illness or systemic disease. The presence of current or recent fever can be indicative of an inflammatory or neoplastic process if the pain is also accompanied by worsening symptoms over time or weight loss.

Subsequent, repeated physical examinations of children with musculoskeletal pain complaints may reveal eventual development and manifestations of rheumatic or other diseases. The need for additional testing should be individualized, depending on the specific symptoms and physical findings. Laboratory screening and/or radiographs should be pursued if there is suspicion of certain underlying disease processes. Possible indicators of a serious, as opposed to a benign, cause of musculoskeletal pain include pain present at rest and relieved by activity, objective evidence of joint swelling on physical examination, stiffness or limited range of motion in joints, bony tenderness, muscle weakness, poor growth and/or weight loss, and constitutional symptoms (e.g., fever, malaise) (Table 162-1). Results of complete blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) measurement are likely to be abnormal in children whose pain is secondary to a bone or joint infection, SLE, or a malignancy. Bone tumors, fractures, and other focal pathology resulting from infection, malignancy, or trauma can often be indentified through imaging studies, including plain radiographs, MRI, and technetium Tc 99m bone scans.

Table 162-1 POTENTIAL INDICATORS OF BENIGN VS SERIOUS CAUSES OF MUSCULOSKELETAL PAIN

| CLINICAL FINDING | BENIGN CAUSE | SERIOUS CAUSE |

|---|---|---|

| Effects of rest vs activity on pain | Relieved by rest and worsened by activity | Relieved by activity and present at rest |

| Time of day pain occurs | End of the day and nights | Morning* |

| Objective joint swelling | No | Yes |

| Joint characteristics | Hypermobile/normal | Stiffness, limited range of motion |

| Bony tenderness | No | Yes |

| Muscle strength | Normal | Diminished |

| Growth | Normal growth pattern or weight gain | Poor growth and/or weight loss |

| Constitutional symptoms (e.g., fever, malaise) | Fatigue without other constitutional symptoms | Yes |

| Laboratory findings | Normal CBC, ESR, CRP | Abnormal CBC, raised ESR and CRP |

| Radiographic findings | Normal | Effusion, osteopenia, radiolucent metaphyseal lines, joint space loss, bony destruction |

CBC, complete blood count; CRP, C-reactive protein level; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

* Cancer pain is often severe and worst at night.

Adapted from Malleson PN, Beauchamp RD: Diagnosing musculoskeletal pain in children, Can Med Assoc J 165:183–188, 2001.

The presence of persistent pain accompanied by psychologic distress, sleep disturbances, and/or functional impairment and in the absence of objective abnormal laboratory or physical findings suggests the diagnosis of a musculoskeletal pain syndrome. All pediatric musculoskeletal pain syndromes share this general constellation of symptoms at presentation. Several more specific pain syndromes routinely seen by pediatric practitioners can be differentiated by anatomic region and associated symptoms. A comprehensive list of pediatric musculoskeletal pain syndromes is provided in Table 162-2; they include growing pains (Chapter 147), fibromyalgia (Chapter 162.1), complex regional pain syndrome (Chapter 162.2), localized pain syndromes, low back pain, and chronic sports-related pain syndromes (e.g., Osgood-Schlatter disease).

Table 162-2 COMMON MUSCULOSKELETAL PAIN SYNDROMES IN CHILDREN BY ANATOMIC REGION

| ANATOMIC REGION | PAIN SYNDROME(S) |

|---|---|

| Shoulder | Impingement syndrome |

| Elbow | |

| Arm | |

| Pelvis and hip | |

| Knee | |

| Leg | |

| Foot | |

| Spine | |

| Generalized |

Adapted from Anthony KK, Schanberg LE: Assessment and management of pain syndromes and arthritis pain in children and adolescents, Rheum Dis Clin N Am 33:625–660, 2007.

Treatment

The primary goal of treatment for pediatric musculoskeletal pain syndromes is to improve function, and the secondary goal is to relieve pain, although these two desirable outcomes may not occur simultaneously. Indeed, it is common for children with musculoskeletal pain syndromes to continue complaining of pain even as they resume normal function (e.g., increased school attendance and participation in extracurricular activities). For all children and adolescents with pediatric musculoskeletal pain syndromes, regular school attendance is crucial, because school attendance is a hallmark of normal functioning in this age group. The dual nature of treatment targeting both function and pain needs to be clearly explained to children and their families to better define the goals by which treatment successes will be measured.

Recommended treatment modalities typically include physical and/or occupational therapy, pharmacologic interventions, and cognitive-behavioral and/or other psychotherapeutic interventions. The overarching goal of physical therapy is to improve children’s physical function and should emphasize participation in aggressive, but graduated aerobic exercise. Pharmacologic interventions should be used judiciously. Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline 10-50 mg orally 30 min before bedtime) are indicated for treatment of sleep disturbance, whereas the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (sertraline 10-20 mg daily) may prove useful in treating depression and anxiety if present. Referral for psychologic evaluation is warranted if these symptoms do not resolve with initial treatment efforts or if suicidal ideation is present. Cognitive-behavioral and/or other psychotherapeutic interventions are typically designed to teach children and adolescents coping skills for controlling the behavioral, cognitive, and physiologic responses to pain. Specific components often include cognitive restructuring, relaxation, distraction, and problem-solving skills; additional targets of therapy include sleep hygiene and activity scheduling, all with the goal of restoring normal sleep patterns and activities of daily living. Family-based approaches may be necessary if barriers to treatment success are identified at the family level. Examples of such barriers are parenting strategies or family dynamics that serve to maintain children’s pain complaints and maladaptive models for pain coping in the family.

Complications and Prognosis

Musculoskeletal pain syndromes can negatively affect both child development and future role functioning. Worsening pain and the associated symptoms of depression and anxiety can lead to substantial school absences, peer isolation, and developmental delays later in adolescence and early adulthood. Specifically, adolescents with musculoskeletal pain syndromes may fail to achieve the level of autonomy and independence necessary for age-appropriate activities such as attending college, living away from home, and maintaining a job. Fortunately, not all children and adolescents with musculoskeletal pain syndromes experience this degree of impairment, and the likelihood of positive health outcomes is increased with multidisciplinary treatment.

Growing Pains

Also known as benign nocturnal pains of childhood, growing pains affect 10-20% of children, with a peak age incidence between 4 and 8 yr. The most common cause of recurrent musculoskeletal pain in children, growing pains are intermittent and bilateral, predominantly affecting the anterior thigh and calf but not joints. Children most commonly describe cramping or aching that occurs in the late afternoon or evening. Pain often wakes the child from sleep but resolves quickly with massage or analgesics; pain is never present the following morning (Table 162-3). Physical findings are normal, and gait is not impaired. Growing pains are generally considered a benign, time-limited condition; however, there is increasing evidence suggesting that growing pains represent a pain amplification syndrome. Indeed, growing pains persist in a significant percentage of children, with some children developing other pain syndromes such as abdominal pain and headaches. Recent studies suggest that growing pains are more likely to persist in children with a parent who has a history of a pain syndrome and in children who have lower pain thresholds. Treatment focuses on reassurance, education, and healthy sleep hygiene.

Table 162-3 DEFINITION OF “GROWING PAINS”

| INCLUSIONS | EXCLUSIONS | |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of pain | Intermittent; some pain-free days and nights | Persistent; increasing intensity |

| Unilateral or bilateral | Bilateral | Unilateral |

| Location of pain | Anterior thigh, calf, posterior knee—in muscles | Join pain |

| Onset of pain | Late afternoon or evening | Pain still present next morning |

| Physical findings | Normal | Swelling, erythema, tenderness; local trauma or infection; reduced joint range of motion; limping |

| Laboratory findings | Normal | Objective evidence of abnormalities, e.g., from erythrocyte sedimentation rate, radiography, bone scanning |

From Evans AM, Scutter SD: Prevalence of “growing pains” in young children, J Pediatr 145:255–258, 2004.

Anthony KK, Schanberg LE. Assessment and management of pain syndromes and arthritis pain in children and adolescents. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2007;33:625-660.

Connelly MA, Schanberg LE. Evaluating and managing pediatric musculoskeletal pain in primary care. In: Walco G, Goldschneider K, Berde A, editors. Pain in children: a practical guide for primary care. New York: Humana Press, 2008.

El-Metwally A, Salimen JJ, Auvinen A, et al. Lower limb pain in a preadolescent population: prognosis and risk factors for chronicity—a prospective 1- and 4-year follow-up study. Pediatrics. 2005;116:673-681.

Evans AM. Growing pains: contemporary knowledge and recommended practice. J Foot Ankle Res. 2008;1:4.

Evans AM, Scutter SD. Prevalence of “growing pains” in young children. J Pediatr. 2004;145:255-258.

Kaspiris A, Zafiropoulou C. Growing pains in children: epidemiological analysis in a Mediterranean population. Joint Bone Spine. 2000;76:486-490.

Scharff L, Langan N, Rotter N, et al. Psychological, behavioral, and family characteristics of pediatric patients with chronic pain: a 1-year retrospective study and cluster analysis. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:432-438.

Stahl M, Kautiainen H, El-Metwally A, et al. Non-specific neck pain in schoolchildren: prognosis and risk factors for occurrence and persistence. A 4-year follow-up study. Pain. 2008;137:316-322.

Uziel Y, Chapnick G, Jaber L, et al. Five-year outcome of children with “growing pains”: correlations with pain threshold. J Pediatr. 2010;156:838-840.

Uziel Y, Hashkes PJ. Growing pains in children. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2007;5:5.

Viswanathan V, Khubchandani RP. Joint hypermobility and growing pains in school children. Clin Experiment Rheumatol. 2008;26:962-966.

162.1 Fibromyalgia

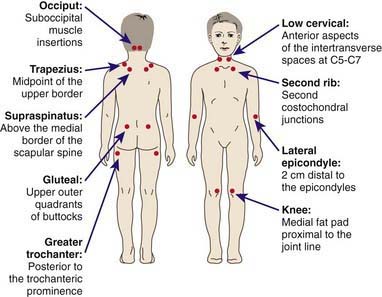

Juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome (JPFS) is a common pediatric musculoskeletal pain syndrome. Approximately 25-40% of children with chronic pain syndromes can be diagnosed with JPFS. Although specific diagnostic criteria for JPFS have not been determined, all children and adolescents with JPFS have diffuse musculoskeletal pain in at least 3 areas of the body that persists for at least 3 mo in the absence of an underlying condition. Results of laboratory tests are normal, and physical examination reveals at least 5 well-defined tender points (Fig. 162-1). Children and adolescents with JPFS also present with many associated symptoms, including nonrestorative sleep, fatigue, chronic anxiety or tension, chronic headaches, subjective soft tissue swelling, and pain modulated by physical activity, weather, and anxiety or stress. There is considerable overlap among the symptoms associated with JPFS and the complaints associated with other functional disorders (e.g., irritable bowel disease, migraines, temporomandibular joint disorder, premenstrual syndrome, mood and anxiety disorders, and chronic fatigue syndrome), raising speculation that these disorders may be part of a larger spectrum of related syndromes.

Although the precise cause of JPFS is unknown, there is an emerging understanding that the development and maintenance of JPFS are related both to biologic and psychologic factors. JPFS is an abnormality of pain processing characterized by disordered sleep physiology, enhanced pain perception with abnormal levels of substance P in cerebrospinal fluid, disordered mood, and dysregulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and other neuroendocrine axes resulting in lower tender point pain thresholds and increased pain sensitivity. Children and adolescents with fibromyalgia also often find themselves in a vicious cycle of pain, whereby symptoms build on one another and contribute to the onset and maintenance of new symptoms (Fig. 162-2).

Figure 162-2 Cycle promoting juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome symptoms and their maintenance.

(Adapted from Anthony KK, Schanberg LE: Juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome, Curr Rheumatol Rep 3:162–171, 2001.)

JPFS has a chronic course that can detrimentally affect child health and development. Adolescents with JPFS who do not receive treatment or are inadequately treated may withdraw from school and the social milieu, complicating their transition to adulthood. Treatment of JPFS generally follows consensus statements of the American Pain Society. The major goals are to restore function and to alleviate pain, and treatment should address co-morbid mood and sleep disorders. Treatment strategies include parent/child education, pharmacologic interventions, exercise-based interventions, and psychologic interventions. Graduated aerobic exercise is the recommended exercise-based intervention, whereas psychologic interventions should include training in pain coping skills, stress management skills, and sleep hygiene. Drug therapies, although partially unsuccessful in isolation, may include tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline 10-50 mg orally 30 minutes before bedtime), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (sertraline 10-20 mg daily), and anticonvulsants. Pregabalin was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of fibromyalgia in adults but has not yet been studied in children. Muscle relaxants are generally not used in children, because they often adversely affect school performance.

American Pain Society. Guidelines for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome pain in adults and children. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2005.

Degotardi PJ, Klass ES, Rosenberg BS, et al. Development and evaluation of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for juvenile fibromyalgia. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:714-723.

Häuser W, Bernardy K, Üçeyler N, et al. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with antidepressants. JAMA. 2009;301:198-212.

Kashikar-Zuck S, Parkins IS, Graham TB, et al. Anxiety, mood, and behavioral disorders among pediatric patients with juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:620-626.

Langhorst J, Klose P, Musial F, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture in fibromyalgia syndrome—a systematic review with a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Rheumatology. 2010;49:778-788.

2009 Milnacipran (Savella) for fibromyalgia. Med Lett. 2009;51:45-46.

Swain NF, Kashikar-Zuck S, Graham TB, et al. Tender point assessment in juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:785-787.

Wang C, Schmid CH, Rones R, et al. A randomized trial of tai chi for fibromyalgia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):743-754.

162.2 Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is characterized by ongoing burning limb pain that is subsequent to an injury, immobilization, or another noxious event affecting the extremity. CRPS1, formerly called reflex sympathetic dystrophy, has no evidence of nerve injury, whereas CRPS2, formerly called causalgia, follows a prior nerve injury. Key associated features are pain disproportionate to the inciting event, persisting allodynia (a heightened pain response to normally non-noxious stimuli), hyperalgesia (exaggerated pain reactivity to noxious stimuli), swelling of distal extremities, and indicators of autonomic dysfunction (i.e., cyanosis, mottling, and hyperhidrosis) (Table 162-4).

Table 162-4 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME

| A diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) requires regional pain, sensory symptoms, plus two neuropathic pain descriptors and two physical signs of autonomic dysfunction: |

| NEUROPATHIC DESCRIPTORS |

| AUTONOMIC DYSFUNCTION |

Data from Wilder RT, Berde CB, Wolohan, M, et al: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy in children: clinical characteristics and follow-up of seventy patients, J Bone Joint Surg Am 74:910–919, 1992.

The diagnosis requires the following: an initiating noxious event or immobilization; continued pain, allodynia, hyperalgesia out of proportion to the inciting event; evidence of edema, skin blood flow abnormalities, or sudomotor activity; and exclusion of other disorders. Associated features include atrophy of hair or nails; altered hair growth; loss of joint mobility; weakness, tremor, dystonia; and sympathetically maintained pain.

Although the majority of pediatric patients with CRPS present with a history of immobilization or minor trauma or repeated stress injury (e.g., caused by competitive sports), a sizeable proportion are unable to identify a precipitating event. Usual age of onset is between 9 and 15 yr, and girls with the disease outnumber boys with the disease by as much as 6 : 1. Childhood CRPS differs from the adult form in that lower extremities rather than upper extremities are most commonly affected. The incidence of CRPS in children is unknown, largely because it is often undiagnosed or diagnosed late, with the diagnosis frequently delayed by nearly a year. Left untreated, CRPS can have severe consequences for children, including bone demineralization, muscle wasting, and joint contractures.

The treatment of CRPS involves a multistage treatment approach. Aggressive physical therapy should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis is made, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) should be added as needed. Physical therapy is recommended 3 or 4 times/wk, and children may need analgesic premedication at the onset. Physical therapy is initially limited to desensitization and then moves to weight-bearing, range-of-motion, and other functional activities. CBT used as an adjunctive therapy targets psychosocial obstacles to fully participating in physical therapy and provides pain coping skills training. Sympathetic and epidural nerve blocks should be attempted only in refractory cases and only under the auspices of a pediatric pain specialist. The intent of both pharmacologic and adjunctive treatments for CRPS is to provide sufficient pain relief to allow the child to participate in aggressive physical rehabilitation. If CRPS is identified and treated early, the majority of children and adolescents with the disease can be treated successfully with low-dose amitriptyline (10-50 mg orally 30 minutes prior to bedtime), aggressive physical therapy, and CBT. Opioids and anticonvulsants such as gabapentin can also be helpful. Notably, multiple studies have shown that noninvasive treatments, particularly physical therapy and CBT, are at least as efficacious as nerve blocks in children with CRPS.

Berde C, Lebel A. Complex regional pain syndromes in children and adolescents. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:252-255.

Higashimoto T, Baldwin EE, Gold JI, et al. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: complex regional pain syndrome type I in children with mitochondrial disease and maternal inheritance. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:390-397.

Leone V, Tornese G, Zerial M, et al. Joint hypermobility and its relationship to musculoskeletal pain in schoolchildren: a cross-sectional study. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:627-632.

Ross J, Grahame R. Joint hypermobility syndrome. BMJ. 2011;342:275-277.

Wilder RT. Management of pediatric patients with complex regional pain syndrome. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:443-448.

162.3 Erythromelalgia

Children with erythromelalgia experience episodes of intense pain, erythema, and heat in their hands and feet (Fig. 162-3) and less commonly in their face, ears, or knees. Symptoms may be triggered by exercise and exposure to heat, and they last for hours and occasionally for days. Although most cases are sporadic, an autosomal dominant hereditary form results from a mutation in the gene SCN9A on chromosome 2q31-32, which is responsible for sodium channel function in dorsal root ganglia. Erythromelalgia is also associated with an array of disorders, including myeloproliferative diseases, peripheral neuropathy, frostbite, hypertension, and rheumatic disease. Treatment includes avoidance of heat exposure as well as other precipitating situations and the utilization of cooling techniques that do not cause tissue damage during attacks. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, narcotics, anesthetic agents, anticonvulsants, and antidepressants as well as biofeedback and hypnosis may be useful in managing pain. Drugs acting on the vascular system (aspirin, sodium nitroprusside, magnesium, misoprostol) may also be effective.