Chapter 198 Tularemia (Francisella tularensis)

Tularemia is a zoonotic infection caused by the gram-negative bacterium Francisella tularensis. Tularemia is primarily a disease of wild animals; human disease is incidental and usually results from contact with blood-sucking insects or live or dead wild animals. The illness caused by F. tularensis is manifested by different clinical syndromes, the most common of which consists of an ulcerative lesion at the site of inoculation with regional lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis. It is also a potential agent of bioterrorism (Chapter 704).

Etiology

F. tularensis, the causative agent of tularemia, is a small, nonmotile, pleomorphic, gram-negative coccobacillus that can be classified into 4 main subspecies (F. tularensis tularensis [type A], F. tularensis holarctica [type B], F. tularensis mediasiatica, and F. tularensis novicida). Type A can be further subdivided into 4 distinct genotypes (A1a, A1b, A2a, A2b) with A1b appearing to produce more serious disease in humans. Type A is found exclusively in North America and is associated with wild rabbits, ticks, and tabanid flies (e.g., deer flies), whereas type B may be found in North America, Europe, and Asia and is associated with semiaquatic rodents, hares, mosquitoes, ticks, tabanid flies, water (e.g., ponds, rivers), and marine animals. Human infections with type B are usually milder and have lower mortality rates compared to infections with type A.

Epidemiology

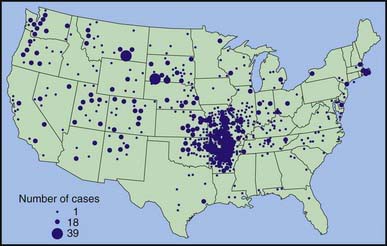

During 1990-2000, a total of 1,368 cases of tularemia were reported in the USA from 44 states, averaging 124 cases (range 86-193) per year (Fig. 198-1). Four states accounted for 56% of all reported tularemia cases: Arkansas, 315 cases (23%); Missouri, 265 cases (19%); South Dakota, 96 cases (7%); and Oklahoma, 90 cases (7%).

Figure 198-1 Reported cases of tularemia in the USA from 1990-2000, based on 1,347 patients reporting county of residence in the continental USA. Alaska reported 10 cases in 4 counties during 1990-2000. The circle size is proportional to the number of cases, ranging from 1 to 39 cases.

(From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Tularemia—United States, 1990-2000, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 51:181–184, 2002.)

Transmission

Of all the zoonotic diseases, tularemia is unusual because of the different modes of transmission of disease. A large number of animals serve as a reservoir for this organism, which can penetrate both intact skin and mucous membranes. Transmission can occur through the bite of infected ticks or other biting insects, by contact with infected animals or their carcasses, by consumption of contaminated foods or water, or through inhalation, as might occur in a laboratory setting. This organism is not, however, transmitted from person to person. In the USA, rabbits and ticks are the principal reservoirs. Most disease due to rabbit exposure occurs in the winter, and disease due to tick exposure occurs in the warmer months (April-September). Amblyomma americanum (Lone Star tick), Dermacentor variabilis (dog tick), and Dermacentor andersoni (wood tick) are the most common tick vectors. These ticks usually feed on infected small rodents and later feed on humans. Taking that blood meal through a fecally contaminated field transmits the infection.

Pathogenesis

The most common portal of entry for human infection is through the skin or mucous membrane. This may occur through the bite of an infected insect or by way of unapparent abrasions. Inhalation or ingestion of F. tularensis can also result in infection. Usually >108 organisms are required to produce infection if they are ingested, but as few as 10 organisms may cause disease if they are inhaled or injected into the skin. Within 48-72 hr after injection into the skin, an erythematous, tender, or pruritic papule may appear at the portal of entry. This papule may enlarge and form an ulcer with a black base, followed by regional lymphadenopathy. Once F. tularensis reaches the lymph nodes, the organism may multiply and form granulomas. Bacteremia may also be present, and although any organ of the body may be involved, the reticuloendothelial system is the most commonly affected.

Conjunctival inoculation may result in infection of the eye with preauricular lymphadenopathy. Inhalation, aerosolization, or hematogenous spread of the organisms can result in pneumonia. Chest roentgenograms of such patients may reveal patchy infiltrates rather than areas of consolidation. Pleural effusions may also be present and may contain blood. In pulmonary infections, mediastinal adenopathy may be present; in oropharyngeal disease, patients may develop cervical lymphadenopathy. Typhoidal tularemia may be used to describe severe bacteremic disease, regardless of the mode of transmission or portal of entry.

Infection with tularemia stimulates the host to produce antibodies. This antibody response, however, has only a minor role in fighting this infection. The body is dependent on cell-mediated immunity to contain and eradicate this infection. Infection is usually followed by specific protection; thus, chronic infection or reinfection is unlikely.

Clinical Manifestations

Although it may vary, the average incubation period from infection until clinical symptoms appear is 3 days (range, 1-21 days). A sudden onset of fever with other associated symptoms is common (Table 198-1). Physical examination may include lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or skin lesions. Various skin lesions have been described, including erythema multiforme and erythema nodosum. Approximately 20% of patients may develop a generalized maculopapular rash that occasionally becomes pustular. These clinical manifestations of tularemia have been divided into various syndromes (Table 198-2).

Table 198-1 COMMON CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF TULAREMIA IN CHILDREN

| SIGN OR SYMPTOM | FREQUENCY (%) |

|---|---|

| Lymphadenopathy | 96 |

| Fever (>38.3°C) | 87 |

| Ulcer/eschar/papule | 45 |

| Pharyngitis | 43 |

| Myalgias/arthralgias | 39 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 35 |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | 35 |

Table 198-2 CLINICAL SYNDROMES OF TULAREMIA IN CHILDREN

| CLINICAL SYNDROME | FREQUENCY (%) |

|---|---|

| Ulceroglandular | 45 |

| Glandular | 25 |

| Pneumonia | 14 |

| Oropharyngeal | 4 |

| Oculoglandular | 2 |

| Typhoidal | 2 |

| Other* | 6 |

* Includes meningitis, pericarditis, hepatitis, peritonitis, endocarditis, and osteomyelitis.

Ulceroglandular and glandular disease are the 2 most common forms of tularemia diagnosed in children. The most common glands involved are usually the cervical or posterior auricular nodes owing to a tick bite on the head or neck. If an ulcer is present, it is erythematous and painful and may last from 1 to 3 wk. The ulcer is located at the portal of entry. After the ulcer develops, regional lymphadenopathy ensues. These nodes may vary in size from 0.5 to 10 cm and may appear singly or in clusters. These affected nodes may become fluctuant and drain spontaneously, but most usually resolve with treatment. Late suppuration of the involved nodes has been described in 25-30% of patients despite effective therapy. Examination of this material from such lymph nodes usually reveals sterile necrotic material.

Pneumonia caused by F. tularensis usually presents as variable parenchymal infiltrates that are unresponsive to β-lactam antimicrobial agents. Inhalation-related infection has been described in laboratory workers who are working with the organism; it results in a relatively high mortality rate. Aerosols from farming activities involving rodent contamination (haying, threshing) or animal carcass destruction with lawn mowers have been reported to cause pneumonia as well. Patchy parenchymal infiltrates can also be demonstrated in other forms of tularemia. Patchy segmental infiltrates, hilar adenopathy, and pleural effusions are the most common abnormalities demonstrated on chest roentgenograms. Patients may also complain of a nonproductive cough, dyspnea, or pleuritic chest pain.

Oropharyngeal tularemia results from consumption of poorly cooked meats or contaminated water. This syndrome is characterized by acute pharyngitis, with or without tonsillitis, and cervical lymphadenitis. Infected tonsils may become large and develop a yellowish-white membrane that may resemble the membranes associated with diphtheria. Gastrointestinal disease may also occur and usually presents with mild, unexplained diarrhea but may progress to rapidly fulminant and fatal disease.

Oculoglandular tularemia is uncommon, but when it does occur, the portal of entry is the conjunctiva. Contact with contaminated fingers or debris from crushed insects is the most common way of applying the organisms to the conjunctiva. The conjunctiva is painful and inflamed, with yellowish nodules and pinpoint ulcerations. Purulent conjunctivitis with ipsilateral preauricular or submandibular lymphadenopathy is referred to as Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome.

Typhoidal tularemia is usually associated with a large inoculum of organisms and usually presents with fever, headaches, and signs or symptoms of endotoxemia. Patients typically are critically ill, and symptoms mimic those with other forms of sepsis. Clinicians practicing in tularemia-endemic regions must always consider this diagnosis in critically ill children.

Diagnosis

The history and physical examination of the patient may suggest the diagnosis of tularemia, especially if the patient lives in or has visited an endemic region. A history of animal or tick exposure may be especially helpful. Hematologic blood tests are nondiagnostic. Results of routine cultures and smears are positive in only approximately 10% of cases. F. tularensis can be cultured in the microbiology laboratory on cysteine–glucose–blood agar, but care should be taken to alert the personnel in the laboratory if this is attempted so that they can take the proper precautions to protect themselves from acquiring infection.

The diagnosis of tularemia is most commonly established through the use of a standard and highly reliable serum agglutination test. In the standard tube agglutination test, a single titer of ≥1 : 160 in a patient with a compatible history and physical findings can establish the diagnosis. A 4-fold increase in titer from paired serum samples collected 2-3 wk apart is also diagnostic. False-negative serologic responses can be obtained early in the infection, and as many as 30% of individuals require longer than 3 wk before testing positive. Once infected, patients may have a positive agglutination test result (1 : 20 to 1 : 80) that may persist for life.

Other testing techniques available include a microagglutination test, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, analysis of urine for tularemia antigen, and polymerase chain reaction. These techniques may become more popular in the future but at this time have a limited role in establishing the diagnosis of tularemia.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of ulceroglandular or glandular tularemia includes cat scratch disease (Bartonella henselae); infectious mononucleosis; Kawasaki syndrome; lymphadenopathy caused by Staphylococcus aureus, group A streptococcus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Toxoplasma gondii, nontuberculous mycobacteria, and Sporothrix schenckii; plague; anthrax; melioidosis; and rat-bite fever. Oculoglandular disease may also occur with other infectious agents, such as B. henselae, Treponema pallidum, Coccidioides immitis, herpes simplex virus, adenoviruses, and the bacterial agents responsible for purulent conjunctivitis. Oropharyngeal tularemia must be differentiated from the same diseases that cause ulceroglandular/glandular disease and from cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex, adenovirus, and other viral or bacterial etiologies. Pneumonic tularemia must be differentiated from the other non–β-lactam-responsive organisms such as Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, mycobacteria, fungi, and rickettsia. Typhoidal tularemia must be differentiated from other forms of sepsis as well as from enteric fever (typhoid and paratyphoid fever) and brucellosis.

Treatment

All strains of F. tularensis are susceptible to gentamicin and streptomycin. Gentamicin (5 mg/kg/day divided bid or tid IV or IM) is the drug of choice for the treatment of tularemia in children because of the limited availability of streptomycin (30-40 mg/kg/day divided bid IM) and the fewer adverse effects of gentamicin. Therapy is typically continued for 7-10 days, but in mild cases, 5-7 days may be sufficient. Chloramphenicol and tetracyclines have been used, but the high relapse rate has limited their use in children. Early data suggested that F. tularensis is susceptible to the 3rd generation cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftriaxone), but clinical case reports demonstrate a nearly universal failure rate with these agents. Quinolones are active against F. tularensis and have been used for treatment of disease due to the type B subspecies holarctica. Further data are required before quinolone therapy can be routinely recommended for human disease caused by the type A subspecies tularensis encountered in North America.

Patients typically have defervescence within 24-48 hr after starting therapy, and relapses are uncommon if gentamicin or streptomycin is used. Patients who have not started on appropriate therapy early may respond more slowly to antimicrobial therapy. Late suppuration of involved lymph nodes may occur despite adequate therapy but usually contain sterile material.

Prognosis

Poor outcomes are associated with a delay in recognition and treatment, but with rapid recognition and treatment, fatalities are exceedingly rare. The mortality rate for severe untreated disease (e.g., pneumonia, typhoidal disease) can be as high as 30% in these situations, but in general, the overall mortality rate is <1%.

Prevention

Prevention of tularemia is based on avoiding exposure. Children living in tick-endemic regions should be taught to avoid tick-infested areas, and families should have a tick control plan for their immediate environment and for their pets. Protective clothing should be worn when entering a tick-infested area, but more importantly, children should undergo frequent tick checks during and after their time in these areas. Skin repellents such as N,N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide (DEET) can be used safely in infants and children to 2 mo of age. Avoiding taking young infants into tick-endemic regions is the most prudent approach. If DEET-containing compounds are used, they should be used sparingly on the exposed skin, avoiding the hands and face on children <1 yr of age. The repellent should be washed off completely after leaving the high-risk region. Clothing repellents that use permethrin have been demonstrated to be an effective addition to the use of protective clothing. If ticks are found on the child, forceps should be used to pull the tick straight out. The skin should be cleansed before and after this procedure.

Children should also be taught to avoid sick and dead animals. Dogs and cats are most likely to bring these animals to a child’s attention. Children should be encouraged to wear gloves while cleaning wild game. A vaccine is available for adults with high-risk vocations (e.g., veterinarians), but there are no recommendations for use in children. Prophylactic antimicrobial agents are not effective in preventing tularemia and should not be used after exposure.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tularemia—Missouri, 2000–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:744-748.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tularemia transmitted by insect bites, Wyoming, 2001–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:170-173.

Eisen RJ, Mead PS, Meyer AW, et al. Ecoepidemiology of tularemia in the southcentral United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:586-594.

Eliasson H, Broman T, Forsman M, et al. Tularemia: current epidemiology and disease management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006;20:289-311.

Kugeler KJ, Mead PS, Janusz AM, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Francisella tularensis in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:863-870.

Nigrovic LE, Wingerter SL. Tularemia. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22:489-504.

Sjöstedt A. Tularemia: History, epidemiology, pathogen physiology, and clinical manifestations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1105:1-29.

Tärnvik A, Chu MC. New approaches to diagnosis and therapy of tularemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1105:378-404.