Chapter 283 Ascariasis (Ascaris lumbricoides)

Etiology

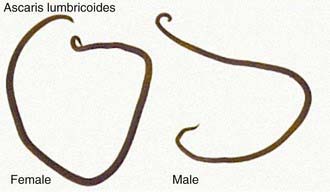

Ascariasis is caused by the nematode, or roundworm, Ascaris lumbricoides. Adult worms of A. lumbricoides inhabit the lumen of the small intestine and have a life span of 10-24 mo. The reproductive potential of Ascaris is prodigious; a gravid female worm produces 200,000 eggs/day. The fertile ova are oval in shape with a thick mammillated covering measuring 45-70 µm in length and 35-50 µm in breadth (Fig. 283-1). After passage in the feces, the eggs embryonate and become infective in 5-10 days under favorable environmental conditions. Adult worms can live for 12-18 mo (Fig. 283-2).

Epidemiology

Ascariasis occurs globally and is the most prevalent human helminthiasis in the world. It is most common in tropical areas of the world where environmental conditions are optimal for maturation of ova in the soil. Approximately 1 billion persons are estimated to be infected, with 4 million cases in the USA. Key factors linked with a higher prevalence of infection include poor socioeconomic conditions, use of human feces as fertilizer, and geophagia. Even though infection can occur at any age, the highest rate is in preschool or early school-aged children. Transmission is primarily hand to mouth but may also involve ingestion of contaminated raw fruits and vegetables. Transmission is enhanced by the high output of eggs by fecund female worms and resistance of ova to the outside environment. Ascaris eggs can remain viable at 5-10°C for as long as 2 yr.

Pathogenesis

Ascaris ova hatch in the small intestine after ingestion by the human host. Larvae are released, penetrate the intestinal wall, and migrate to the lungs by way of the venous circulation. The parasites then cause pulmonary ascariasis as they enter into the alveoli and migrate through the bronchi and trachea. They are subsequently swallowed and return to the intestines, where they mature into adult worms. Female Ascaris begin depositing eggs in 8-10 wk.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical presentation depends on the intensity of infection and the organs involved. Most individuals have low to moderate worm burdens and have no symptoms or signs. The most common clinical problems are due to pulmonary disease and obstruction of the intestinal or biliary tract. Larvae migrating through these tissues may cause allergic symptoms, fever, urticaria, and granulomatous disease. The pulmonary manifestations resemble Loeffler syndrome and include transient respiratory symptoms such as cough and dyspnea, pulmonary infiltrates, and blood eosinophilia. Larvae may be observed in the sputum. Vague abdominal complaints have been attributed to the presence of adult worms in the small intestine, although the precise contribution of the parasite to these symptoms is difficult to ascertain. A more serious complication occurs when a large mass of worms leads to acute bowel obstruction. Children with heavy infections may present with vomiting, abdominal distention, and cramps. In some cases, worms may be passed in the vomitus or stools. Ascaris worms occasionally migrate into the biliary and pancreatic ducts, where they cause cholecystitis or pancreatitis. Worm migration through the intestinal wall can lead to peritonitis. Dead worms can serve as a nidus for stone formation. Studies show that chronic infection with A. lumbricoides (often coincident with other helminth infections) impairs growth, physical fitness, and cognitive development.

Diagnosis

Microscopic examination of fecal smears can be used for diagnosis because of the high number of eggs excreted by adult female worms (see Fig. 283-1). A high index of suspicion in the appropriate clinical context is needed to diagnose pulmonary ascariasis or obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract. Ultrasound examination of the abdomen is capable of visualizing intraluminal adult worms.

Treatment

Although several chemotherapeutic agents are effective against ascariasis, none have documented utility during the pulmonary phase of infection. Treatment options for gastrointestinal ascariasis include albendazole (400 mg PO once, for all ages), mebendazole (100 mg bid PO for 3 days or 500 mg PO once for all ages), or pyrantel pamoate (11 mg/kg PO once, maximum 1 g). Piperazine citrate (75 mg/kg/day for 2 days maximum 3.5 g/day), which causes neuromuscular paralysis of the parasite and rapid expulsion of the worms, is the treatment of choice for intestinal or biliary obstruction and is administered as syrup through a nasogastric tube. Surgery may be required for cases with severe obstruction. Nitazoxanide (100 mg bid PO for 3 days for children 1-3 yr of age, 200 mg bid PO for 3 days for children 4-11 yr, and 500 mg bid PO for 3 days for adolescents and adults) produces cure rates comparable with single-dose albendazole.

Prevention

Although ascariasis is the most prevalent worm infection in the world, little attention has been given to its control. Anthelmintic chemotherapy programs can be implemented in 1 of 3 ways: (1) offering universal treatment to all individuals in an area of high endemicity; (2) offering treatment targeted to groups with high frequency of infection, such as children attending primary school; or (3) offering individual treatment based on intensity of current or past infection. Improving sanitary conditions and sewage facilities, discontinuing the practice of using human feces as fertilizer, and education are the most effective long-term preventive measures.

Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet. 2006;367:1521-1532.

Gilles HM, Hoffman PS. Treatment of intestinal parasitic infections: a review of nitazoxanide. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18:95-97.

Jardim-Botelho A, Raff S, Rodrigues DA, et al. Hookworm, Ascaris lumbricoides infection and polyparasitism associated with poor cognitive performance in Brazilian schoolchildren. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:994-1004.

Keiser J, Utzinger J. Efficacy of current drugs against soil-transmitted helminth infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;299:1937-1948.

Shah OJ, Zargar SA, Robbani I. Biliary ascariasis: a review. World J Surg. 2006;30:1500-1506.