Chapter 286 Enterobiasis (Enterobius vermicularis)

Etiology

The cause of enterobiasis, or pinworm infection, is Enterobius vermicularis, which is a small (1 cm in length), white, threadlike nematode, or roundworm, that typically inhabits the cecum, appendix, and adjacent areas of the ileum and ascending colon. Gravid females migrate at night to the perianal and perineal regions, where they deposit up to 15,000 eggs. Ova are convex on 1 side and flattened on the other and have diameters of ∼30 × 60 µm. Eggs embryonate within 6 hr and remain viable for 20 days. Human infection occurs by the fecal-oral route typically by ingestion of embryonated eggs that are carried on fingernails, clothing, bedding, or house dust. After ingestion, the larvae mature to form adult worms in 36-53 days.

Epidemiology

Enterobiasis infection occurs in individuals of all ages and socioeconomic levels. It is prevalent in regions with temperate climates and is the most common helminth infection in the USA. It infects 30% of children worldwide, and humans are the only known host. Infection occurs primarily in institutional or family settings that include children. The prevalence of pinworm infection is highest in children 5-14 yr of age. It is common in areas where children live, play, and sleep close together, thus facilitating egg transmission. Because the life span of the adult worm is short, chronic parasitism is likely due to repeated cycles of reinfection. Autoinoculation can occur in individuals who habitually put their fingers in their mouth.

Pathogenesis

Enterobius infection may cause symptoms by mechanical stimulation and irritation, allergic reactions, and migration of the worms to anatomic sites where they become pathogenic. Enterobius infection has been associated with concomitant Dientamoeba fragilis infection, which causes diarrhea.

Clinical Manifestations

Pinworm infection is innocuous and rarely causes serious medical problems. The most common complaints include itching and restless sleep secondary to nocturnal perianal or perineal pruritus. The precise cause and incidence of pruritus are unknown but may be related to the intensity of infection, psychologic profile of the infected individual and his or her family, or allergic reactions to the parasite. Eosinophilia is not observed in most cases, because tissue invasion does not occur. Aberrant migration to ectopic sites occasionally may lead to appendicitis, chronic salpingitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, peritonitis, hepatitis, and ulcerative lesions in the large or small bowel.

Diagnosis

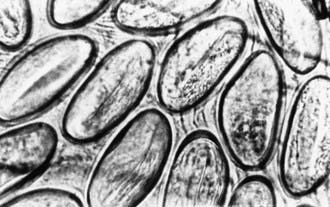

A history of nocturnal perianal pruritus in children strongly suggests enterobiasis. Definitive diagnosis is established by identification of parasite eggs or worms. Microscopic examination of adhesive cellophane tape pressed against the perianal region early in the morning frequently demonstrates eggs (Fig. 286-1). Repeated examinations increase the chance of detecting ova; a single examination detects 50% of infections, 3 examinations 90%, and 5 examinations 99%. Worms seen in the perianal region should be removed and preserved in 75% ethyl alcohol until microscopic examination can be performed. Digital rectal examination may also be used to obtain samples for a wet mount. Routine stool samples rarely demonstrate Enterobius ova.

Treatment

Anthelmintic drugs should be administered to infected individuals and their family members. A single oral dose of mebendazole (100 mg PO for all ages) repeated in 2 wk results in cure rates of 90-100%. Alternative regimens include a single oral dose of albendazole (400 mg PO for all ages) repeated in 2 wk, or a single dose of pyrantel pamoate (11 mg/kg PO, maximum 1 g). Morning bathing removes a large portion of eggs. Frequent changing of underclothes, bed clothes, and bed sheets decreases environmental egg contamination and may decrease the risk for autoinfection.

Prevention

Household contacts can be treated at the same time as the infected individual. Repeated treatments every 3-4 mo may be required in circumstances with repeated exposure, such as with institutionalized children. Good hand hygiene is the most effective method of prevention.

Arca MJ, Gates RL, Groner JI, et al. Clinical manifestations of appendiceal pinworms in children: an institutional experience and a review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:372-375.

Girgikardesler N, Kurt A, Kilimciglu AA. Transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis: evaluation of the role of Enterobius vermicularis. Parasitol Int. 2008;57:72-75.

Kucik CJ, Martin GL, Sortor BV. Common intestinal parasites. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1161-1168.

Sizer AR, Nirmal DM, Shannon J, et al. A pelvic mass due to infestation of the fallopian tube with Enterobius vermicularis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:462-463.

Tandan T, Pollard AJ, Money DM, et al. Pelvic inflammatory disease associated with Enterobius vermicularis. Arch Dis Child. 2002;86:439-440.