Chapter 296 Echinococcosis (Echinococcus granulosus and Echinococcus multilocularis)

Etiology

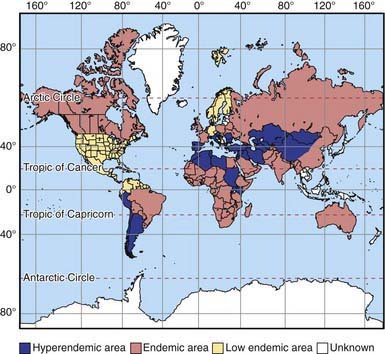

Echinococcosis (hydatid disease or hydatidosis) is the most widespread, serious human cestode infection in the world (Fig. 296-1). Two major Echinococcus species are responsible for distinct clinical presentations, E. granulosus (cystic hydatid disease) and the more malignant E. multilocularis (alveolar hydatid disease). The adult parasite is a small (2-7 mm) tapeworm with only 2-6 segments that inhabits the intestines of dogs, wolves, dingoes, jackals, coyotes, and foxes. These carnivores pass the eggs in their stool, which contaminates the soil, pasture, and water, as well as their own fur. Domestic animals such as sheep, goats, cattle, and camels ingest E. granulosus eggs while grazing. Humans are also infected by consuming food or water contaminated with eggs or by direct contact with infected dogs. The larvae hatch, penetrate the gut, and are carried by the vascular or lymphatic systems to the liver, lungs, and less commonly bones, brain, or heart.

Figure 296-1 Worldwide distribution of cystic echinococcosis.

(From McManus DP, Zhang W, Li J, et al: Echinococcosis, Lancet 362:1295–1304, 2003.)

E. granulosus shows high intraspecific variation. One distinct variant is found in a sylvatic wolf/moose cycle in North America and Siberia. The transmission cycle of E. multilocularis is similar to that of E. granulosus, except that this species is mainly sylvatic and uses small rodents as its natural intermediate hosts. The rodents are consumed by foxes, their natural predators, and sometimes by dogs and cats.

Epidemiology

There is potential for transmission of this parasite to humans wherever there are herd animals and dogs. Even in urban areas, dogs may be infected by eating entrails after home slaughter of domestic animals. Cysts have been detected in up to 10% of the human population in northern Kenya and Western China. In South America, the disease is prevalent in sheepherding areas of the Andes, the beef-herding areas of the Brazilian/Argentine Pampas, and Uruguay. Among developed countries, the disease is recognized in Italy, Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Australia, and is reemergent in dogs in Great Britain. In North America, transmission occurs by way of the sylvatic cycle in Alaska, Canada, and Isle Royale on Lake Superior, as well as in foci of the domestic cycle in sheep raising areas of western USA.

Transmission of E. multilocularis occurs primarily in temperate climates of Northern Europe, Siberia, Turkey, and China. Transmission is decreasing among native peoples in Alaska and Canada as dogs are replaced by mechanized forms of transportation. A separate species, Echinococcus vogeli, causes polycystic disease similar to alveolar hydatidosis in South America.

Pathogenesis

In areas endemic for E. granulosus, the parasite is often acquired in childhood, but liver cysts require many years to become large enough to detect or cause symptoms. In children, the lung is a common site, whereas in adults 70% of cysts develop in the right lobe of the liver. Cysts can also develop in bone, the genitourinary system, bowels, subcutaneous tissues, and brain. The host surrounds the primary cyst with a tough, fibrous capsule. Inside this capsule, the parasite produces a thick lamellar layer with the consistency of a soft-boiled egg white. This layer supports a thin germinal layer of cells responsible for production of thousands of juvenile-stage parasites (protoscolices) that remain attached to the wall or float free in the cyst fluid. Smaller internal daughter cysts may develop within the primary cyst capsule. The fluid in a healthy cyst is colorless, crystal clear, and watery. After medical treatment or with bacterial infection, it may become thick and bile stained.

Infection with E. multilocularis resembles a malignancy. The secondary reproductive units bud externally and are not confined within a single well-defined structure. Furthermore, the cyst tissues are poorly demarcated from those of the host, which makes these cysts unsuitable for surgical removal. The secondary cysts are also capable of distant metastatic spread. The growing cyst mass eventually replaces a significant portion of the liver and compromises adjacent tissues and structures.

Clinical Manifestations

In the liver, many cysts never become symptomatic and regress spontaneously or produce relatively nonspecific symptoms. Symptomatic cysts can cause increased abdominal girth, hepatomegaly, a palpable mass, vomiting, or abdominal pain. However, the more serious complications result from compression of adjacent structures, spillage of cyst contents, and location of cysts in sensitive areas, such as the reproductive tract, brain, and bone. Anaphylaxis can occur with cyst rupture or spontaneous spillage, due to trauma or intraoperatively. Spillage can also be catastrophic long-term, since each protoscolex can form a new cyst. Jaundice due to cystic hydatid disease is rare. In the lung, cysts produce chest pain, cough, or hemoptysis. Bone cysts may cause pathologic fractures, and cysts in the genitourinary system may produce hematuria or infertility.

In alveolar hydatid disease, cyst tissue continues to proliferate and may separate and metastasize distantly. The proliferating mass compromises hepatic tissue or the biliary system and causes progressive obstructive jaundice and hepatic failure. Symptoms also occur from expansion of extrahepatic foci.

Diagnosis

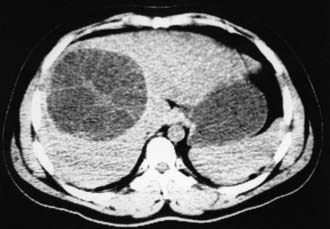

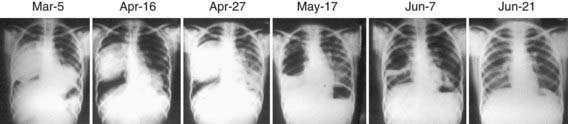

Subcutaneous nodules, hepatomegaly, or a palpable abdominal mass may be found. The parasite cannot be recovered from any easily accessible body fluid unless a lung cyst ruptures, after which protoscolices or layers of cyst wall may briefly be seen in sputum. Ultrasonography is the most valuable tool for both the diagnosis and treatment of cystic hydatid disease of the liver. The presence of internal membranes and falling echogenic cyst material (hydatid sand) observed in real time aid in the diagnosis. Alveolar disease is less cystic in appearance and resembles a diffuse solid tumor. CT findings (Fig. 296-2) are similar to those of ultrasonography and may at times be useful in distinguishing alveolar from cystic hydatid disease in geographic regions where both occur. CT or MRI is also important in planning a surgical intervention. Lung hydatid is usually apparent on chest x-ray (Fig. 296-3).

Figure 296-2 CT image of a hepatic Echinococcus granulosus hydatid cyst. The membranes of multiple internal daughter cysts are visible within the primary cyst structure.

(Courtesy of John R. Haaga, MD, University Hospitals, Cleveland, Ohio.)

Figure 296-3 Serial chest x-rays of a young Kenyan woman with bilateral hydatid cysts. After 2 mo of albendazole therapy, sudden rupture of the right cyst was associated with massive aspiration and acute respiratory distress.

Serologic studies may be useful in confirming a diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis, but the false-negative rate may be >50%. Most patients with alveolar hydatidosis develop detectable antibody responses. Current tests use crude or partially purified antigens that can cross react in individuals infected with other parasitic infections, such as cysticercosis or schistosomiasis.

Differential Diagnosis

Benign hepatic cysts are common but can be distinguished by the absence of either internal membranes or hydatid sand. The density of bacterial hepatic abscesses is distinct from the watery cystic fluid characteristic of E. granulosus infection, but hydatid cysts may also be complicated by secondary bacterial infection. Alveolar echinococcosis is often confused with hepatoma and cirrhosis and presents features suggestive of pancreatic carcinoma, metastatic liver disease, and cholangitis.

Treatment

For simple, accessible cysts surrounded by tissue, ultrasound- or CT-guided Percutaneous Aspiration, Instillation (hypertonic saline or another scolicidal agent) and Re-aspiration (PAIR) is the preferred therapy. Compared with surgical treatment alone, PAIR plus albendazole results in similar cyst disappearance with fewer adverse events and fewer days in the hospital. Compared to albendazole alone, PAIR with or without albendazole provides significantly better cyst reduction and symptomatic relief. Spillage with PAIR is surprisingly uncommon, but prophylactic albendazole therapy is routinely administered >1 wk prior to PAIR or surgery and continued for 1 mo thereafter. Albendazole treatment for 4 wk prior to any procedure is probably warranted, but may remove the diagnostic value of aspiration in some cases. PAIR is contraindicated in pregnancy and for bile-stained cysts, which should not be injected with a scolicidal agent because of increased risk for biliary complications.

Indications for surgery are the presence of large liver cysts with multiple daughter cysts, single superficially situated liver cysts that may rupture spontaneously or as the result of a trauma, infected cysts, cysts communicating with the biliary tree and/or exerting pressure on adjacent vital organs, and cysts in the lung, brain, kidney, or bones. For conventional surgery, the inner cyst wall (only laminate and germinal layers are of parasite origin) can be easily peeled from the fibrous layer, although some studies suggest that removal of the whole capsule has a better outcome. The cavity should then be topically sterilized and either closed or filled with omentum. Considerable care must be taken to avoid spillage of cyst contents, because cyst fluid contains viable protoscolices, each capable of producing secondary cysts wherever it lodges. An additional risk is anaphylaxis due to spilled cyst fluid, so it is therefore useful to employ a surgeon experienced in this surgery.

Nonpregnant patients with cysts not amenable to PAIR or surgery or with contraindications can be managed with albendazole (15 mg/kg/day divided bid PO for 1-6 mo, maximum 800 mg/day). A favorable response occurs in 40-60% of patients. Adverse effects include occasional alopecia, mild gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated transaminases on prolonged use. Because of leukopenia, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends that blood counts be monitored at the beginning and every 2 wk during therapy. Corticosteroids are not indicated unless patients show signs of immediate hypersensitivity. Ultrasonographic indications of successful therapy are reduction in diameter, a change in shape from spherical to elliptic or flat, progressive increase in echogenicity and density of cyst fluid, and detachment of membranes from the capsule (water lily sign).

Alveolar hydatidosis is frequently incurable by any modality, except by partial hepatectomy, lobectomy, or liver transplantation for limited disease. Medical therapy with albendazole may slow the progression of alveolar hydatidosis, and some patients have been maintained on long-term suppressive therapy, but the infection generally recurs if albendazole is stopped.

Prognosis

Factors predictive of success with chemotherapy are age of the cyst (<2 yr), low internal complexity of the cyst, and small size. The site of the cyst is not important, although cysts in bone respond poorly. For alveolar hydatidosis, if surgical removal is unsuccessful, the average mortality is 92% by 10 yr after diagnosis.

Prevention

Important measures to interrupt transmission include, above all, thorough handwashing, avoiding contact with dogs in endemic areas, boiling or filtering water when camping, proper disposal of animal carcasses, and proper meat inspection. Strict procedures for proper disposal of refuse from slaughterhouses must be instituted and followed so that dogs or wild carnivores do not have access to entrails. Other useful measures are control or treatment of the feral dog population and regular praziquantel treatment of pets and working dogs in endemic areas. A vaccine is available.

Buishi I, Walters T, Guildea Z, et al. Reemergence of canine Echinococcus granulosus infection, Wales. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:568-571.

Eckert J, Deplazes P. Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:107-135.

McManus DP, Zhang W, Li J, et al. Echinococcosis. Lancet. 2003;362:1295-1304.

Moro PL, Schantz PM. Echinococcosis: historical landmarks and progress in research and control. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100:703-714.

Nasseri Moghaddam S, Abrishami A, et al: Percutaneous needle aspiration, injection, and reaspiration with or without benzimidazole coverage for uncomplicated hepatic hydatid cysts, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 19:CD003623, 2006.