Chapter 323 Intestinal Duplications, Meckel Diverticulum, and Other Remnants of the Omphalomesenteric Duct

323.1 Intestinal Duplication

Duplications of the intestinal tract are rare anomalies that consist of well-formed tubular or spherical structures firmly attached to the intestine with a common blood supply. The lining of the duplications resembles that of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Duplications are located on the mesenteric border and can communicate with the intestinal lumen. Duplications can be classified into 3 categories: localized duplications, duplications associated with spinal cord defects and vertebral malformations, and duplications of the colon. Occasionally (10-15% of cases), multiple duplications are found.

Localized duplications can occur in any area of the GI tract but are most common in the ileum and jejunum. They are usually cystic or tubular structures within the wall of the bowel. The cause is unknown, but their development has been attributed to defects in recanalization of the intestinal lumen after the solid stage of embryologic development. Duplication of the intestine occurring in association with vertebral and spinal cord anomalies (hemivertebra, anterior spina bifida, band connection between lesion and cervical or thoracic spine) is thought to arise from splitting of the notochord in the developing embryo. Duplication of the colon is usually associated with anomalies of the urinary tract and genitals. Duplication of the entire colon, rectum, anus, and terminal ileum can occur. The defects are thought to be secondary to caudal twinning, with duplication of the hindgut, genital, and lower urinary tracts.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms depend on the size, location, and mucosal lining. Duplications can cause bowel obstruction by compressing the adjacent intestinal lumen, or they can act as the lead point of an intussusception or a site for a volvulus. If they are lined by acid-secreting mucosa, they can cause ulceration, perforation, and hemorrhage of or into the adjacent bowel. Patients can present with abdominal pain, vomiting, palpable mass, or acute GI hemorrhage. Intestinal duplications in the thorax (neuroenteric cysts) can manifest as respiratory distress. Duplications of the lower bowel can cause constipation or diarrhea or be associated with recurrent prolapse of the rectum.

The diagnosis is suspected on the basis of the history and physical examination. Radiologic studies such as barium studies, ultrasonography, CT, and MRI are helpful but usually nonspecific, demonstrating cystic structures or mass effects. Radioisotope technetium scanning can localize ectopic gastric mucosa. The treatment of duplications is surgical resection and management of associated defects.

323.2 Meckel Diverticulum and Other Remnants of the Omphalomesenteric Duct

Melissa Kennedy and Chris A. Liacouras

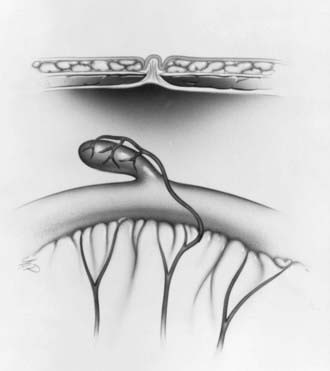

A Meckel diverticulum is a remnant of the embryonic yolk sac, which is also referred to as the omphalomesenteric duct or vitelline duct. The omphalomesenteric duct connects the yolk sac to the gut in a developing embryo and provides nutrition until the placenta is established. Between the 5th and 7th wk of gestation, the duct attenuates and separates from the intestine. Just before this involution, the epithelium of the yolk sac develops a lining similar to that of the stomach. Partial or complete failure of involution of the omphalomesenteric duct results in various residual structures. Meckel diverticulum is the most common of these structures and is the most common congenital GI anomaly, occurring in 2-3% of all infants. A typical Meckel diverticulum is a 3-6 cm outpouching of the ileum along the antimesenteric border 50-75 cm from the ileocecal valve (Fig. 323-1). The distance from the ileocecal valve depends on the age of the patient. Other omphalomesenteric duct remnants occur infrequently, including a persistently patent duct, a solid cord, or a cord with a central cyst or a diverticulum associated with a persistent cord between the diverticulum and the umbilicus.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms of a Meckel diverticulum usually arise in the 1st or 2nd yr of life (average 2.5 yr), but initial symptoms can occur in the 1st decade. The majority of symptomatic Meckel diverticula are lined by an ectopic mucosa, including an acid-secreting mucosa that causes intermittent painless rectal bleeding by ulceration of the adjacent normal ileal mucosa. This ectopic mucosa is most commonly of gastric origin, but it can also be pancreatic, jejunal, or a combination of these tissues. Unlike the upper duodenal mucosa, the acid is not neutralized by pancreatic bicarbonate.

The stool is typically described as brick colored or currant jelly colored. Bleeding can cause significant anemia but is usually self-limited because of contraction of the splanchnic vessels, as patients become hypovolemic. Bleeding from a Meckel diverticulum can also be less dramatic, with melanotic stools.

Less often, a Meckel diverticulum is associated with partial or complete bowel obstruction. The most common mechanism of obstruction occurs when the diverticulum acts as the lead point of an intussusception. The mean age of onset of obstruction is younger than that for patients presenting with bleeding. Obstruction can also result from intraperitoneal bands connecting residual omphalomesenteric duct remnants to the ileum and umbilicus. These bands cause obstruction by internal herniation or volvulus of the small bowel around the band. A Meckel diverticulum occasionally becomes inflamed (diverticulitis) and manifests similarly to acute appendicitis. These children are older, with a mean of 8 yr of age. Diverticulitis can lead to perforation and peritonitis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of omphalomesenteric duct remnants depends on the clinical presentation. If an infant or child presents with significant painless rectal bleeding, the presence of a Meckel diverticulum should be suspected because Meckel diverticulum accounts for 50% of all lower GI bleeds in children <2 yr of age.

Confirmation of a Meckel diverticulum can be difficult. Plain abdominal radiographs are of no value, and routine barium studies rarely fill the diverticulum. The most sensitive study is a Meckel radionuclide scan, which is performed after intravenous infusion of technetium-99m pertechnetate. The mucus-secreting cells of the ectopic gastric mucosa take up pertechnetate, permitting visualization of the Meckel diverticulum (Fig. 323-2). The uptake can be enhanced with various agents, including cimetidine, ranitidine, glucagon, and pentagastrin. The sensitivity of the enhanced scan is approximately 85%, with a specificity of approximately 95%. A false-negative scan may be seen in anemic patients; although false-positive results are uncommon, they have been reported with intussusception, appendicitis, duplication cysts, arteriovenous malformations, and tumors. Other methods of detection include radio-labeled tagged red blood cell scan (the patient must be actively bleeding), abdominal ultrasound, superior mesenteric angiography, abdominal CT scan, or exploratory laparoscopy. In patients who present with intestinal obstruction or a picture of appendicitis with omphalomesenteric duct remnants, the diagnosis is rarely made before surgery.

Figure 323-2 Meckel scan demonstrating accumulation of technetium in the stomach superior bladder (inferior) and in the acid-secreting mucosa of a Meckel diverticulum.

The treatment of a symptomatic Meckel diverticulum is surgical excision.

Baldisserotto M, Maffazzoni DR, Dora MD. Sonographic findings of Meckel’s diverticulitis in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;80:425-428.

Emamian SA, Shalaby-Rana E, Majd M. The spectrum of heterotopic gastric mucosa in children detected by Tc-99m pertechnetate scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2001;26:529-535.

Fenton LZ, Buonomo C, Share JC, et al. Small intestinal obstruction by remnants of the omphalomesenteric duct: findings on contrast enema. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30:165-167.

Lee KH, Yeung CK, Tam YH, et al. Laparascopy for definitive diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1291-1293.

Rerksuppaphol S, Hutson JM, Oliver MR. Ranitidine-enhanced 99mtechnetium pertechnetate imaging in children improves the sensitivity of identifying heterotopic gastric mucosa in Meckel’s diverticulum. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004 May;20(5):323-325.

Swaniker F, Soldes O, Hirschl RB. The utility of technetium-99m pertechnetate scintigraphy in the evaluation of patients with Meckel’s diverticulum. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:760-764.