Chapter 337 Tumors of the Digestive Tract

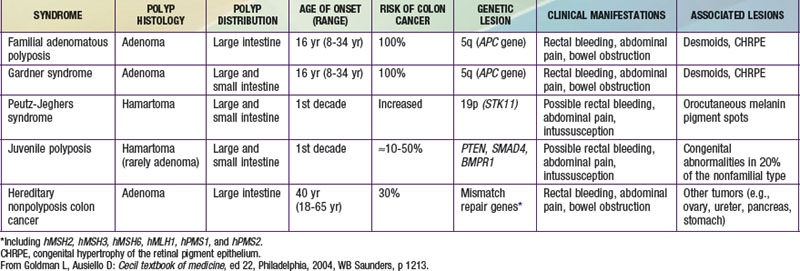

Tumors of the digestive tract are mostly polypoid. They are also commonly syndromic tumors and tumors with known genetic identification (see ![]() Table 337-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com). They usually manifest as painless rectal bleeding, but they can serve as lead points for intussusception.

Table 337-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com). They usually manifest as painless rectal bleeding, but they can serve as lead points for intussusception.

Hamartomatous Tumors

Hamartomas are benign tumors composed of tissues that are normally found in an organ but that are not organized normally. Juvenile, retention, or inflammatory polyps are hamartomatous polyps, which represent the most common intestinal tumors of childhood, occurring in 1-2% of children. Patients generally present in the 1st decade, most often at age 2-5 yr, and rarely at <1 year. Polyps may be found anywhere in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, most commonly in the colon or rectum; they are often solitary but may be multiple.

Histologically, juvenile polyps are composed of hamartomatous collections of mucus-filled glandular and stromal elements with inflammatory infiltrate, covered with a thin layer of epithelium. These polyps are often bulky, vascular, and prone to bleed as their growth exceeds their blood supply with resultant mucosal ulceration, or autoamputation with bleeding from a residual central artery.

Patients often present with painless rectal bleeding after defecation. Bleeding is generally scant and intermittent; rarely iron deficiency anemia is the chief presenting symptom. Extensive bleeding can occur but is generally self-limited, requiring supportive care until the bleeding stops spontaneously after autoamputation. Occasionally endoscopic polypectomy is required for control of bleeding. Abdominal pain or cramps are uncommon unless associated with intussusception. Patients can present with prolapse, with a dark, edematous, pedunculated mass protruding from the rectum. Mucus discharge and pruritus are associated with prolapse.

Patients presenting with rectal bleeding require thorough work-up; differential diagnosis includes anal fissure, other intestinal polyposis syndromes, Meckel’s diverticulum, inflammatory bowel disease, intestinal infections, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, or coagulopathy.

Diagnosis and therapy are best accomplished via endoscopy. Polyps may be visualized via air-contrast barium enema, but this provides no therapeutic advantage and is uncomfortable and usually performed without sedation or anesthesia. Colonoscopy affords opportunity for biopsy, polypectomy by snare cautery, and visualization of synchronous lesions; up to 50% of children have ≥1 additional polyp, and ∼20% may have >5 polyps. Retrieved polyps should be sent for histologic evaluation for definitive diagnosis.

Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome

Patients with juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS) present with multiple juvenile polyps, ≥5 but typically 50-200. There is usually a family history with an autosomal dominant pattern. Polyps may be isolated to the colon or distributed throughout the GI tract. Alterations in transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathways have been identified in some JPS patients and families. Approximately 20% have mutations of SMAD4 (18q21.1). Bone morphogenic protein receptor 1A gene [BMPR1A (10q22.3)] mutations have been identified in another 20% of patients. Genetic testing is available for both of these mutations.

Histologically, these polyps are identical to solitary juvenile polyps; however, the GI malignancy risk is greatly increased (10-50%). Most malignancy is colorectal, though gastric, upper GI, and pancreatic tumors have been described. The risk of malignancy is greater in patients with >3 polyps and a positive family history. These patients should therefore undergo routine esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, and upper GI contrast studies. Serial polypectomy or polyp biopsy should be undertaken if possible. If dysplasia or malignant degeneration is found, a total colectomy is indicated.

Juvenile polyposis of infancy is characterized by early polyp formation (<2 yr of age) and may be associated with protein-losing enteropathy, hypoproteinemia, anemia, failure to thrive, and intussusception. Early endoscopic or surgical intervention may be needed.

Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder (incidence, ∼1 : 120,000) characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation and extensive GI hamartomatous polyposis. Macular pigmented lesions may be dark brown to dark blue and are found primarily around the lips and oral mucosa, although these lesions may also be found on the hands, feet, or perineum (Fig. 337-1). Lesions can fade by puberty or adulthood.

Figure 337-1 Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Note the pigmentary changes.

(From Swartz MH: Textbook of physical diagnosis: history and examination, ed 4. Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 295.)

Polyps are primarily found in the small intestine (in order of prevalence: jejunum, ileum, duodenum) but may also be colonic or gastric. Histologically polyps are defined by normal epithelium surrounding bundles of smooth muscle arranged in a branching or frondlike pattern. Symptoms arising from GI polyps in PJS are similar to those of other polyposis syndromes, namely bleeding and abdominal cramping from obstruction or recurrent intussusception. Patients can require repeated laparotomies and intestinal resections.

The diagnosis of PJS is made clinically in patients with histologically proven hamartomatous polyps if two of three conditions are met: positive family history with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation, and small bowel polyposis. Genetic testing can reveal mutations in STK11 (LKB1; 19p13.3), a serine-threonine kinase that acts as a tumor-suppressor gene. Up to 94% of patients with clinical characteristics of PJS have a mutation at this locus. Only 50% of patients with PJS have an affected family member, suggesting a high rate of spontaneous mutations.

Patients with PJS have increased risk of GI and extraintestinal malignancies. Up to 50% of patients develop cancer, usually by middle age. Colorectal, breast, and reproductive tumors are most common. GI surveillance should begin in childhood (by age 8 yr or when symptoms occur) with upper and lower endoscopy. The small bowel may be evaluated radiographically, with push-pull enteroscopy, or with wireless capsule endoscopy. Polyps >1.5 cm should be removed. Screening for breast, gynecologic, and testicular cancers should be routine after age 20 yr.

Pten Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome

Mutations in the tumor suppressor gene protein tyrosine phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) are associated with several rare autosomal dominant syndromes, including Cowden syndrome and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome. These patients present with multiple hamartomas in skin (99%), brain, breast, thyroid, endometrium, and GI tract (60%). Patients are at increased risk for breast and thyroid malignancies; the risk of GI cancer does not appear to be elevated.

Apc-Associated Polyposis Syndromes

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is the most common genetic polyposis syndrome (incidence 1 : 5,000 to 1 : 17,000 persons) and is characterized by numerous adenomatous polyps throughout the colon, as well as extraintestinal manifestations. FAP and related syndromes (attenuated FAP; Gardner and Turcot syndromes) are linked to mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, a tumor suppressor mapped to 5q21. APC regulates degradation of β-catenin, a protein with roles in regulation of the cytoskeleton, tissue architecture organization, cell migration and adherence, and numerous other functions. Intracellular accumulation of β-catenin may be responsible for colonic epithelial cell proliferation and adenoma formation. More than 400 APC mutations have been described, and up to 30% of patients present with no family history (spontaneous mutations).

Polyps generally develop late in the 1st decade of life or in adolescence (mean age, 16 yr). At the time of diagnosis, ≥5 adenomatous polyps are present in the colon and rectum. By young adulthood the number typically increases to hundreds (sometimes thousands). Adenomatous polyps (or adenomas) are precancerous lesions within the surface epithelium of the intestine, displaying various degrees of dysplasia. Without intervention, the risk of developing colon cancer is 100% by the 5th decade of life (average age of cancer diagnosis is 40 yr). Other GI adenomas can develop, particularly in the stomach and duodenum (50-90%).The risk of periampullary or duodenal carcinoma is significantly elevated (4-12% lifetime risk). Young patients with FAP are also at increased risk for developing hepatoblastoma (1.6% before age 5 yr).

Extra-intestinal manifestations of FAP may be present from birth or develop in early childhood. Lesions include congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE), desmoid tumors, epidermoid cysts, osteomas, fibromas, and lipomas. Many of these benign soft tissue tumors appear before intestinal polyps develop. Expression of extraintestinal findings can depend on location of mutation on the APC gene.

Other syndromes associated with APC mutations include Gardner syndrome, classically characterized by multiple colorectal polyps, desmoid tumors, and soft tissue tumors including fibromas, osteomas (typically mandibular), epidermoid cysts, and lipomas. Once thought to be a distinct clinical entity, Gardner syndrome shares many characteristics with FAP. Up to 20% of FAP patients present with the classic extraintestinal manifestations once associated with Gardner syndrome. Some (but not all) cases of Turcot’s syndrome are also related to APC. These patients present with colorectal polyposis and primary brain tumors (medulloblastoma). Attenuated FAP is characterized by a significantly increased risk of colorectal cancer but fewer polyps than classic FAP (average 30 polyps). The average age of cancer diagnosis in this form of FAP is 50-55. Upper GI tumors and extraintestinal manifestations may be present but are less common.

The clinical presentation of FAP is variable. Polyps are generally asymptomatic initially (and might remain so). If symptoms develop, they can include rectal bleeding (possibly with secondary anemia), cramping, and diarrhea. The presence of symptoms at presentation does not correlate with malignant changes. Diagnosis should be suspected from family history, and ensuing sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy is confirmatory. Histologic examination of biopsied polyps reveals adenomatous architecture (as opposed to inflammatory or hamartomatous polyps found in other polyposis syndromes) with varying degrees of dysplasia. Genetic testing for APC mutations is clinically available, and index patients should be tested. If a mutation is identified, affected family members should be screened and appropriate genetic counseling should be provided. If the index patient does not demonstrate a defined mutation, family members may undergo genetic testing, which might identify novel APC mutations. Children with identified APC mutations must undergo careful surveillance, with sigmoidoscopy every 1-2 yr. Once polyps are identified, colonoscopy should be performed annually. Patients should also have upper endoscopy after development of colonic polyps to monitor for gastric and especially duodenal lesions.

Treatment of FAP requires prophylactic proctocolectomy to prevent cancer. Ileoanal pull-through procedures restore bowel continuity, with acceptable functional outcomes. Resection should be done once polyposis has become extensive (>20-30) or by the mid-teens. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents such as sulindac and cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors such as celecoxib might inhibit polyp progression. No guidelines have been established, however, and their efficacy in preventing malignant transformation of existing polyps is unknown.

Carcinoma

Primary carcinomas of the small bowel or colon are extremely rare in children. Development of adenocarcinoma in adolescence or early adulthood is usually associated with a genetic predisposition or syndrome such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), hereditary nonpolyposis colon carcinoma (HNPCC), Peutz-Jehgers syndrome, or inflammatory bowel disorders such as Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis.

Colorectal carcinoma, though rare (reported incidence of 1 case per 1,000,000 persons <19 yr of age), is the most common primary GI carcinoma in children. Many cases are spontaneous (i.e., not associated with a genetic predisposition or syndrome). Histologically, tumors tend to be poorly differentiated and pathologically aggressive. Patients may be asymptomatic, or they present with nonspecific signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, constipation, and vomiting. Delay in diagnosis is common. Many patients present with advanced-stage disease, with microscopic or gross metastases at the time of diagnosis. Surgical resection is the primary treatment modality, though with delayed presentation and advanced-stage disease, complete resection may not be possible. Chemotherapy and radiation have a limited role in patients with metastatic disease.

Lymphoma

Lymphoma is the most common GI malignancy in the pediatric population. Approximately 30% of children with non-Hodgkins lymphoma (NHL) present with abdominal tumors. Patients with immunocompromise have an increased incidence of lymphoma. Predisposing conditions include HIV/AIDS, agammaglobulinemia, long-standing celiac disease, and bone marrow or solid organ transplantation. Lymphoma can occur anywhere in the GI tract, but it most commonly occurs in the ileocecal region and small bowel. Presenting symptoms include crampy abdominal pain, vomiting, obstruction, or palpable mass. Lymphoma should be considered in patients >3 yr old who present with intussusception.

Nodular Lymphoid Hyperplasia

Lymphoid follicles in the lamina propria and submucosa of the gut normally aggregate in Peyer’s patches, most prominently in the distal ileum. These follicles can become hyperplastic, forming nodules that protrude into the lumen of the bowel. Some suggested etiologies are infectious (classically Giardia), allergic, or immunologic. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (NLH) has been described in infants with enterocolitis secondary to dietary protein sensitivity. This phenomenon has also been described in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and Castleman disease. Patients may be asymptomatic or may present with abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, diarrhea, or intussusception. NLH usually resolves spontaneously and rarely requires therapy; in cases with severe pain or bleeding, corticosteroids may be effective.

Carcinoid Tumor

Carcinoids are neuroendocrine tumors of enterochromaffin cells, which can occur throughout the GI tract, but in children they are typically found in the appendix. This is often an incidental diagnosis at the time of appendectomy. Complete resection of small tumors (<1 cm) with clear surgical margins is curative. Appendiceal tumors >2 cm mandate further bowel resection. Carcinoid tumors outside the appendix (small intestine, rectum, stomach) are more likely to metastasize. Metastatic carcinoid tumor within the liver can give rise to the carcinoid syndrome. Serotonin, 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), or histamine are elaborated by the tumor, and elevated serum levels cause cramps, diarrhea, vasomotor disturbances (flushing), bronchoconstriction, and right heart failure. The diagnosis is confirmed by elevated urinary 5-hydroxyindoloacetic acid (5-HIAA). Symptomatic relief of carcinoid symptoms may be achieved with administration of somatostatin analogs (octreotide).

Leiomyoma

Leiomyomas are rare benign tumors that can arise anywhere in the GI tract, though most often in the stomach, jejunum, or distal ileum. Age of presentation is variable, from the newborn period through adolescence. Patients may be asymptomatic or can present with an abdominal mass, obstruction, intussusception, volvulus, or pain and bleeding from central necrosis of the tumor. Surgical resection is the treatment of choice. Pathologically, these tumors may be difficult to distinguish from malignant leiomyosarcomas. Smooth muscle tumors occur with increased incidence in children with HIV or those requiring immunosuppression after transplantation.

Gastrointestinal Stromal Cell Tumors

Gastrointestinal stromal cell tumors (GIST) are intestinal mesenchymal tumors that probably arise from interstitial cells of Cajal or their precursors. Historically, these may have been diagnosed as tumors of smooth muscle or neural cell origin. The World Health Organization recognized GIST in 1990 as a distinct neoplasm. Typically GISTs arise in adults, after the 3rd decade of life. Cases have also been reported in the pediatric population, generally in adolescents. In the pediatric population tumors are most commonly found in the stomach, though they can occur anywhere in the GI tract or even the mesentery or omentum. Patients may be asymptomatic or can present with an abdominal mass, lower GI bleeding, or obstruction. Treatment consists of surgical en bloc resection of local disease. GISTs occurring in adults are typically associated with mutation in the KIT oncogene. This mutation is less commonly found in pediatric GISTs. Adjuvant therapy for KIT+ lesions is imatinib mesylate, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor available as oral therapy. Patients with persistent disease or metastases might benefit from treatment.

Vascular Tumors

Vascular malformations and hemangiomas are rare in children. The usual presentation is painless rectal bleeding, which may be chronic or acute, with massive or even fatal hemorrhage. There are usually no associated symptoms, though intussusception has been described. Half of patients have associated cutaneous hemangiomas or telangiectasias. These lesions may be associated with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. About half of these lesions are in the colon and can be identified on colonoscopy. During acute bleeding episodes, bleeding can be localized via nuclear medicine bleeding scans, mesenteric angiography, or endoscopy. Colonic bleeding may be controlled by endoscopic means. Surgical intervention is required only occasionally for isolated lesions.

Attard TM, Tajouri T, Peterson KD, et al. Familial adenomatous polyposis in children younger than age 10 years: a multidisciplinary clinic experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:207-212.

Erdman SH. Pediatric adenomatous polyposis syndromes: an update. Curr Gastroenterol Reports. 2007;9:237-244.

Hill DA, Furman WL, Billups CA, et al. Colorectal carcinoma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathologic review. J Clin Onco. 2007;25:5808-5814.

Ladd AP, Grosfeld J. Gastrointestinal tumors in adolescents and children. Sem Pediatr Surg. 2006;15:37-47.

Lynch HT, Lynch JF, Lynch PM, et al. Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: molecular genetics, genetic counseling, diagnosis and management. Familial Cancer. 2008;7:27-39.

Moglia A, Menciassi A, Dario P. Clinical update: endoscopy for small-bowel tumours. Lancet. 2007;370:114-116.

Pappo AS, Janeway KA. Pediatric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:15-34.

Rubin BP, Heinrich MC, Corless CL. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Lancet. 2007;369:1731-1740.

Sidhu R, Sanders DS, McAlindon ME, et al. Capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy: modern modalities to investigate the small bowel in paediatrics. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:154-159.

Vidal I, Podevin G, Piloquet H, et al. Followup and surgical management of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:419-425.

von Allmen D. Intestinal polyposis syndromes: progress in understanding and treatment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:316-320.