Chapter 343 Pancreatitis

343.1 Acute Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis, the most common pancreatic disorder in children, is increasing in incidence. At least 30-50 cases are now seen in major pediatric centers per year. In children, blunt abdominal injuries, multisystem disease, biliary stones or microlithiasis (sludging), and drug toxicity are the most common etiologies. Although many drugs and toxins can induce acute pancreatitis in susceptible persons, in children, valproic acid, L-asparaginase, 6-mercaptopurine, and azathioprine are the most common causes of drug-induced pancreatitis. Other cases follow organ transplantation or are due to infections, metabolic disorders, and mutations in susceptibility genes (Chapter 343.2). Less than 5% of cases are idiopathic (Table 343-1).

Table 343-1 ETIOLOGY OF ACUTE PANCREATITIS IN CHILDREN

DRUGS AND TOXINS

GENETIC

INFECTIOUS

OBSTRUCTIVE

SYSTEMIC DISEASE

TRAUMATIC

After an initial insult, such as ductal disruption or obstruction, there is premature activation of trypsinogen to trypsin within the acinar cell. Trypsin then activates other pancreatic proenzymes, leading to autodigestion, further enzyme activation, and release of active proteases. Lysosomal hydrolases co-localize with pancreatic proenzymes within the acinar cell. Pancreastasis (similar in concept to cholestasis) with continued synthesis of enzymes occurs. Lecithin is activated by phospholipase A2 into the toxic lysolecithin. Prophospholipase is unstable and can be activated by minute quantities of trypsin. After the insult, cytokines and other proinflammatory mediators are released.

The healthy pancreas is protected from autodigestion by pancreatic proteases that are synthesized as inactive proenzymes; digestive enzymes that are segregated into secretory granules at pH 6.2 by low calcium concentration, which minimizes trypsin activity; the presence of protease inhibitors both in the cytoplasm and zymogen granules; and enzymes that are secreted directly into the ducts.

Histopathologically, interstitial edema appears early. Later, as the episode of pancreatitis progresses, localized and confluent necrosis, blood vessel disruption leading to hemorrhage, and an inflammatory response in the peritoneum can develop.

Clinical Manifestations

Mild Acute Pancreatitis

The patient with acute pancreatitis has severe abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, and possibly fever. The pain is epigastric or in either upper quadrant and steady, often resulting in the child’s assuming an antalgic position with hips and knees flexed, sitting upright, or lying on the side. The child is very uncomfortable and irritable and appears acutely ill. The abdomen may be distended and tender and a mass may be palpable. The pain can increase in intensity for 24-48 hr, during which time vomiting may increase and the patient can require hospitalization for dehydration and might need fluid and electrolyte therapy. The prognosis for complete recovery in the acute uncomplicated case is excellent. The incidence of acute pancreatitis is increasing.

Severe Acute Pancreatitis

Severe acute pancreatitis is rare in children. In this life-threatening condition, the patient is acutely ill with severe nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Shock, high fever, jaundice, ascites, hypocalcemia, and pleural effusions can occur. A bluish discoloration may be seen around the umbilicus (Cullen sign) or in the flanks (Grey Turner sign). The pancreas is necrotic and can be transformed into an inflammatory hemorrhagic mass. The mortality rate, which is ∼20%, is related to the systemic inflammatory response syndrome with multiple organ dysfunction, shock, renal failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, massive gastrointestinal bleeding, and systemic or intra-abdominal infection. The percentage of necrosis seen on CT scan and failure of pancreatic tissue to enhance on CT scan (suggesting necrosis) predicts the severity of the disease.

Diagnosis

Acute pancreatitis is usually diagnosed by measurement of serum lipase and amylase activities. Serum lipase is now considered the test of choice for acute pancreatitis as it is more specific than amylase for acute inflammatory pancreatic disease and should be determined when pancreatitis is suspected. The serum lipase rises by 4-8 hr, peaks at 24-48 hr, and remains elevated 8-14 days longer than serum amylase. Serum lipase can be elevated in nonpancreatic diseases. The serum amylase level is typically elevated for up to 4 days. A variety of other conditions can also cause hyperamylasemia without pancreatitis (Table 343-2). Elevation of salivary amylase can mislead the clinician to diagnose pancreatitis in a child with abdominal pain. The laboratory can separate amylase isoenzymes into pancreatic and salivary fractions. Initially, serum amylase levels are normal in 10-15% of patients.

Table 343-2 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF HYPERAMYLASEMIA

PANCREATIC PATHOLOGY

SALIVARY GLAND PATHOLOGY

INTRA-ABDOMINAL PATHOLOGY

SYSTEMIC DISEASES

Other laboratory abnormalities that may be present in acute pancreatitis include hemoconcentration, coagulopathy, leukocytosis, hyperglycemia, glucosuria, hypocalcemia, elevated γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, and hyperbilirubinemia.

X-ray of the chest and abdomen might demonstrate nonspecific findings. The chest x-ray might demonstrate platelike atelectasis, basilar infiltrates, elevation of the hemidiaphragm, left- (rarely right-) sided pleural effusions, pericardial effusion, and pulmonary edema. Abdominal x-rays might demonstrate a sentinel loop, dilation of the transverse colon (cutoff sign), ileus, pancreatic calcification (if recurrent), blurring of the left psoas margin, a pseudocyst, diffuse abdominal haziness (ascites), and peripancreatic extraluminal gas bubbles.

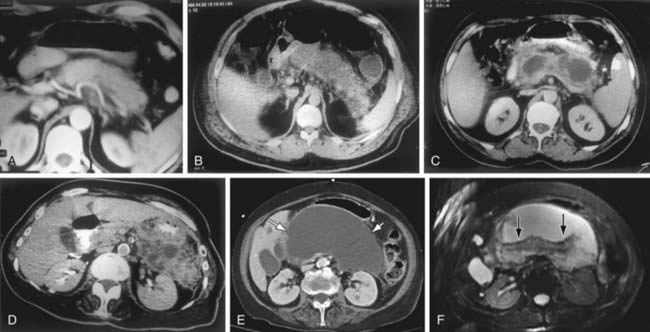

CT scanning has a major role in the diagnosis and follow-up of children with pancreatitis. Findings can include pancreatic enlargement, a hypoechoic, sonolucent edematous pancreas, pancreatic masses, fluid collections, and abscesses (Fig. 343-1); ≥20% of children with acute pancreatitis initially have normal imaging studies. In adults, CT findings are the basis of a widely accepted prognostic system. Ultrasonography is more sensitive than CT scanning for the diagnosis of biliary stones. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are essential in the investgation of recurrent pancreatitis, nonresolving pancreatitis, and disease associated with gallbladder pathology. Endoscopic ultrasonography also helps visualize the pancreaticobiliary system.

Figure 343-1 Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appearance of pancreatitis. A, Mild acute pancreatitis. Arterial phase spiral CT. Diffuse enlargement of pancreas without fluid accumulation. B, Severe acute pancreatitis. Lack of enhancement of the pancreatic parenchyma due to the necrosis of the entire pancreatic gland. C, Pancreatic pseudocyst. A round fluid collection with thin capsule is seen within the lesser sac. D, Acute severe pancreatitis and peripancreatic abscess formation. Peripancreatic abscess formation is observed within the peripancreatic and the left anterior pararenal space. E, Pancreatic necrosis. A well-defined fluid attenuation collection in the pancreatic bed (white arrows) seen on CECT imaging. F, The same collection is more complex appearing on the corresponding T2-weighted MR image. The internal debris and necrotic tissue are better appreciated because of the superior soft tissue contrast of MR imaging (black arrows).

(A-D, From Elmas N: The role of diagnostic radiology in pancreatitis, Eur J Radiol 38[2]:120–132, 2001, Figs 1, 3b, 4a, and 5. E-F, From Soakar A, Rabinowitz CB, Sahani DV: Cross-sectional imaging in acute pancreatitis, Radiol Clin North Am 45[3]:447–460, 2007, Fig 14.)

Treatment

The aims of medical management are to relieve pain and restore metabolic homeostasis. Analgesia should be given in adequate doses. Fluid, electrolyte, and mineral balance should be restored and maintained. Nasogastric suction is useful in patients who are vomiting. While vomiting, the patient should be maintained with nothing by mouth. Recovery is usually complete within 4-5 days. Refeeding can commence when vomiting has resolved. Early refeeding decreases the complication rate and length of stay.

In severe pancreatitis, prophylactic antibiotics are used to prevent infected pancreatic necrosis or to treat infected necrosis. Gastric acid is suppressed. Endoscopic therapy can be of benefit when pancreatitis is caused by anatomic abnormalities, such as strictures or stones. Enteral alimentation by mouth, nasogastric tube, or nasojejunal tube (in severe cases or for those intolerant of oral or nasogastric feedings), within 2-3 days of onset, reduces the length of hospitalization. In children, surgical therapy of nontraumatic, acute pancreatitis is rarely required but may include drainage of necrotic material or abscesses.

Prognosis

Children with uncomplicated acute pancreatitis do well and recover within 4-5 days. When pancreatitis is associated with trauma or systemic disease, the prognosis is typically related to the associated medical conditions.

Frossard JL, Steer ML, Pastor CM. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2008;371:143-152.

Jacobson B, Vander Vliet M, Hughes M, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of clear liquids versus low-fat solid diet as the initial meal in mild acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:946-951.

Kandula L, Lowe ME. Etiology and outcome of acute pancreatitis in infants and toddlers. J Pediatr. 2008;152:106-110.

Makola D, Krenitsky J, Parrish C, et al. Efficacy of enteral nutrition for the treatment of pancreatitis using standard enteral formula. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2347-2355.

Nydegger A, Heine R, Ranuh R. Changing incidence of acute pancreatitis: 10-year experience at the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1313-1316.

Petrov MS, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MGH, et al. Enteral nutrition and the risk of mortality and infectious complications in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1111-1117.

Werlin SL, Kugathasan S, Frautschy B. Pancreatitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:591-595.

Whitcomb DC. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2142-2150.

343.2 Chronic Pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis in children is often due to genetic mutations or due to congenital anomalies of the pancreatic or biliary ductal system. Mutations in the PRSS1 gene (cationic trypsinogen) located on the long arm of chromosome 7, SPINK 1 gene (pancreatic trypsin inhibitor) located on chromosome 5, in the cystic fibrosis gene (CFTR), and chymotrypsin C all lead to chronic pancreatitis (see Table 343-1).

Cationic trypsinogen has a trypsin-sensitive cleavage site. Loss of this cleavage site in the abnormal protein permits uncontrolled activation of trypsinogen to trypsin, which leads to autodigestion of the pancreas. Mutations in PRSS1 act in an autosomal dominant fashion with incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity. Symptoms often begin in the 1st decade but are usually mild at the onset. Although spontaneous recovery from each attack occurs in 4-7 days, episodes become progressively severe. Clinically, hereditary pancreatitis may be diagnosed by the presence of the disease in successive generations of a family. An evaluation during symptom-free intervals may be unrewarding until calcifications, pseudocysts, or pancreatic exocrine and endocrine insufficiency develops (Fig. 343-2). Chronic pancreatitis is a risk factor for future development of pancreatic cancer. Multiple mutations of the PRSS1 gene associated with hereditary pancreatitis have been described.

Figure 343-2 Chronic pancreatitis. Computed tomogram showing calcification in the head of the pancreas (black arrow) and dilated pancreatic duct (white arrow) in a 12 yr old patient.

(Courtesy of Dr. Janet Reid.) (From Wyllie R, Hyams JS, editors: Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders.)

Trypsin inhibitor acts as a fail-safe mechanism to prevent uncontrolled autoactivation of trypsin. Mutations in the SPINK1 gene have been associated with recurrent or chronic pancreatitis. In SPINK1 mutations, this fail-safe mechanism is lost; this gene may be a modifier gene and not the direct etiologic factor.

Mutations of the cystic fibrosis gene (CFTR), which cause cystic fibrosis with pancreatic sufficiency or which do not typically produce pulmonary disease, can cause chronic pancreatitis, possibly due to ductal obstruction. A mutation in the Chymotrypsin C gene, causing a gain of function, is a newly described genetic etiology of recurrent pancreatitis. Indications for genetic testing include recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, a family history of pancreatitis, or unexplained pancreatitis in children.

Other conditions associated with chronic, relapsing pancreatitis are hyperlipidemia (types I, IV, and V), hyperparathyroidism, and ascariasis. Previously, most cases of recurrent pancreatitis in childhood were considered idiopathic; with the discovery of at least 4 gene families associated with recurrent pancreatitis, this has changed. Congenital anomalies of the ductal systems, such as pancreas divisum are more common than previously recognized.

Autoimmune pancreatitis typically manifests with jaundice, abdominal pain, and weight loss. The pancreas is typically enlarged and the pancreas is hypodense on CT. The pathogenesis is unknown. Treatment is with steroids. There have been only a few case reports of this condition in children.

Juvenile tropical pancreatitis is the most common form of chronic pancreatitis in developing equatorial countries. The highest prevalence is in the Indian state of Kerala. Tropical pancreatitis occurs during late childhood or early adulthood, manifesting with abdominal pain and irreversible pancreatic insufficiency followed by diabetes mellitus within 10 years. The pancreatic ducts are obstructed with inspissated secretions, which later calcify. This condition is associated with mutations in the SPINK gene in 50% of cases.

A thorough diagnostic evaluation of every child with >1 episode of pancreatitis is indicated. Serum lipid, calcium, and phosphorus levels are determined. Stools are evaluated for ascaris, and a sweat test is performed. Plain abdominal films are evaluated for the presence of pancreatic calcifications. Abdominal ultrasound or CT scanning is performed to detect the presence of a pseudocyst. The biliary tract is evaluated for the presence of stones. After genetic counseling, evaluation of PRSS1, SPINK1, CFTR, and CRTC genotypes can be measured.

MRCP and ERCP are techniques that can be used to define the anatomy of the gland and are mandatory if surgery is considered. MRCP is the test of choice when endotherapy is not being considered and should be performed as part of the evaluation of any child with idiopathic, nonresolving, or recurrent pancreatitis and in patients with a pseudocyst before drainage. In these cases a previously undiagnosed anatomic defect that may be amenable to endoscopic or surgical therapy may be detected. Endoscopic treatments include sphincterotomy, stone extraction, drainage on pseudocysts, and insertion of pancreatic or biliary endoprosthetic stents. These treatments allow successful nonsurgical management of conditions previously requiring surgical intervention.

De Boeck K, Weren M, Poresmans M, et al. Pancreatitis among patients with cystic fibrosis: correlation with pancreatic status and genotype. Pediatrics. 2005;115:463-469.

Dua K, Miranda A, Santharam R, et al. ERCP in the evaluation of abdominal pain in children. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1081-1085.

Kingsnorth A, O’Reilly D. Acute pancreatitis. BMJ. 2006;332:1072-1076.

Tipnis N, Dua K, Werlin S. A retrospective assessment of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol. 2008;46:59-64.

Werlin SL, Taylor A. ERCP. In: Howard ER, Stringer MD, Colombani PM, editors. Surgery of the liver, bile ducts and pancreas in children. ed 2. London: STM Publishing; 2002:509-520.

Witt H, Apte M, Keim V, et al. Chronic pancreatitis: challenges and advances in pathogenesis, genetics, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1557-1573.