Chapter 379 Foreign Bodies of the Airway

Epidemiology and Etiology

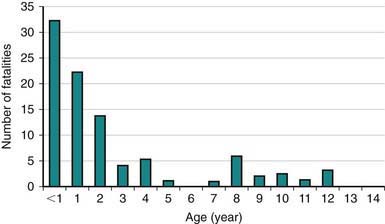

Infants and toddlers use their mouths to explore their surroundings. Most victims of foreign body aspiration are older infants and toddlers (Fig. 379-1). Children <3 yr of age account for 73% of cases. Preambulatory toddlers can aspirate objects given to them by older siblings. One third of aspirated objects are nuts, particularly peanuts. Fragments of raw carrot, apple, dried beans, popcorn, and sunflower or watermelon seeds are also aspirated, as are small toys or toy parts.

Figure 379-1 Number of fatalities vs victim age, all fatalities.

(From Milkovich SM, Altkorn R, Chen X, et al: Development of the small parts cylinder: lessons learned, Laryngoscope 118[11]:2082–2086, 2008.)

The most serious complication of foreign body aspiration is complete obstruction of the airway. Globular or round food objects such as hotdogs, grapes, nuts, and candies are the most frequent offenders. Hot dogs are rarely seen as airway foreign bodies because toddlers who choke on hot dogs asphyxiate at the scene unless treated immediately. Complete airway obstruction is recognized in the conscious child as sudden respiratory distress followed by inability to speak or cough.

Clinical Manifestations

Three stages of symptoms may result from aspiration of an object into the airway:

Diagnosis

A positive history must never be ignored. A negative history may be misleading. Choking or coughing episodes accompanied by wheezing are highly suggestive of an airway foreign body. Because nuts are the most common bronchial foreign body, the physician specifically questions the toddler’s parents about nuts. If there is any history of eating nuts, bronchoscopy is carried out promptly.

Most airway foreign bodies lodge in a bronchus (right bronchus ∼58% of cases); the location is the larynx or trachea in ∼10% of cases. An esophageal foreign body can compress the trachea and be mistaken for an airway foreign body. The patient is asymptomatic and the radiograph is normal in 15-30% of cases. Opaque foreign bodies occur in only 10-25% of cases. CT can help define radiolucent foreign bodies such as fish bones. If there is a high index of suspicion, bronchoscopy should be performed despite negative imaging studies. History is the most important factor in determining the need for bronchoscopy.

Treatment

The treatment of choice for airway foreign bodies is prompt endoscopic removal with rigid instruments. Bronchoscopy is deferred only until preoperative studies have been obtained and the patient has been prepared by adequate hydration and emptying of the stomach. Airway foreign bodies are usually removed the same day the diagnosis is first considered.

379.1 Laryngeal Foreign Bodies

Complete obstruction asphyxiates the child unless it is promptly relieved with the Heimlich maneuver (Chapter 62 and Figs. 62-6 and 62-7). Objects that are partially obstructive are usually flat and thin. They lodge between the vocal cords in the sagittal plane, causing symptoms of croup, hoarseness, cough, stridor, and dyspnea.

379.2 Tracheal Foreign Bodies

Choking and aspiration occurs in 90% of patients with tracheal foreign bodies, stridor in 60%, and wheezing in 50%. Posteroanterior and lateral soft tissue neck radiographs (airway films) are abnormal in 92% of children, whereas chest radiographs are abnormal in only 58%.

379.3 Bronchial Foreign Bodies

Radiologic evaluation—posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs—are standard in the assessment of infants and children suspected of having aspirated a foreign object. The abdomen is included. A good expiratory posteroanterior chest film is most helpful. During expiration the bronchial foreign body obstructs the exit of air from the obstructed lung, producing obstructive emphysema, air trapping, with persistent inflation of the obstructed lung and shift of the mediastinum toward the opposite side (Fig. 379-2). Air trapping is an immediate complication, in contrast to atelectasis, which is a late finding. Lateral decubitus chest films or fluoroscopy can provide the same information but are unnecessary. History and physical examination, not radiographs, determine the indication for bronchoscopy.

Figure 379-2 A, Normal inspiratory chest radiograph in a toddler with a peanut fragment in the left main bronchus. B, Expiratory radiograph of the same child showing the classic obstructive emphysema (air trapping) on the involved (left) side. Air leaves the normal right side allowing the lung to deflate. The medium shifts toward the unobstructed side.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Policy statement—prevention of choking among children. Pediatrics. 2010;125:601-607.

Cohen S, Avital A, Godfrey S, et al. Suspected foreign body inhalation in children: what are the indications for bronchoscopy? J Pediatr. 2009;155:276-280.

Kadmon G, Stenr T, Bron–Harley E, et al. Computerized scoring system for the diagnosis of foreign body aspiration in children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(11):839-843.

Milkovich SM, Altkorn R, Chen X, et al. Development of the small parts cylinder: lessons learned. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(11):2082-2086.

Nova A, Muntz H, Clary R. Utility of conventional radiography in pediatric airway foreign bodies. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;107:834-838.

Shah RK, Patel A, Lander L, et al. Management of foreign bodies obstructing the airway in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136(4):373-379.

Wang K, Harnden A, Thomson A. Foreign body inhalation in children. BMJ. 2010;341:455-456.