Chapter 460 Polycythemia

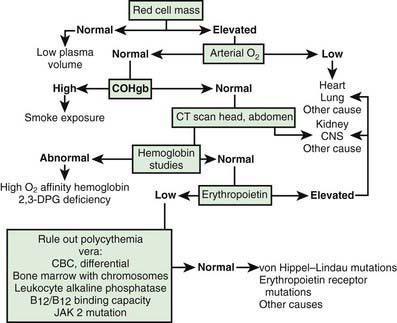

Polycythemia exists when the red blood cell (RBC) count, hemoglobin level, and total RBC volume all exceed the upper limits of normal. In postpubertal individuals, an RBC mass > 25% above the mean normal value (based on body surface area), or a hematocrit level > 60 (in males) or > 56 (in females) indicate absolute erythrocytosis. A decrease in plasma volume, such as occurs in acute dehydration and burns, may result in a high hemoglobin value. These situations are more accurately designated as hemoconcentration or relative polycythemia because the RBC mass is not increased and normalization of the plasma volume restores hemoglobin to normal levels. Once the diagnosis of true polycythemia is made, sequential studies should be done to determine the underlying etiology (see ![]() Fig. 460-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com).

Fig. 460-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com).

Figure 460-1 Sequential studies to evaluate polycythemia. CBC, complete blood count; CNS, central nervous system; COHgb, carboxyhemoglobin; 2,3-DPG, 2,3-diphosphoglycerate.

Primary Polycythemia (Polycythemia Rubra Vera)

Pathogenesis

Polycythemia vera is a clonal panmyeloproliferative disorder and is rare in children. A gain of function mutation of JAK2, a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase, has been found in 75% of adult patients with polycythemia vera but in a much lower percentage of children with this condition. The erythropoietin receptor is normal, and serum erythropoietin levels are normal or low.

In vitro cultures do not require added erythropoietin to stimulate growth of erythroid precursors. Diagnostic criteria for polycythemia vera were revised by the WHO in 2008 and are listed in Table 460-1.

Table 460-1 WHO DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR POLYCYTHEMIA VERA

MAJOR CRITERIA

Hgb or Hct > 99th percentile of reference range for age, sex, or altitude of residence

Hgb > 17 g/dL (men) or Hgb > 15 g/dL (women) if associated with a sustained increase of ≥ 2 g/dL from baseline that cannot be attributed to correction of iron deficiency

elevated red cell mass > 25% above mean normal predicted value.

MINOR CRITERIA

DIAGNOSIS

Both major criteria and one minor criteria OR First major criteria and 2 minor criteria.

From Tefferi A, Vardiman JW: Classification and diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasms: the 2008 World Health Organization criteria and point-of-care diagnostic algorithms. Leukemia 22:14–22, 2008.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients with polycythemia vera usually have hepatosplenomegaly. Erythrocytosis may cause hypertension, headache, shortness of breath, or neurologic symptoms. Granulocytosis may cause diarrhea or pruritus from histamine release. Thrombocytosis (with or without platelet dysfunction) may cause thrombosis or hemorrhage.

Treatment

Phlebotomy is the initial treatment of choice. Iron supplementation should be given to prevent viscosity problems from iron-deficient microcytosis. Antiplatelet agents (aspirin) may reduce the risks of thrombosis and bleeding in patients with marked thrombocytosis. If these treatments are unsuccessful, antiproliferative treatments (hydroxyurea, anagrelide, interferon-α) may be helpful. The risk of transformation of the disease into myelofibrosis or acute leukemia has diminished with discontinuation of the use of alkylating agents and radioactive phosphorus. Prolonged survival is not unusual.

Cario H. Childhood polycythemias/erythrocytoses: classification, diagnosis, clinical presentation, and treatment. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:137-145.

Cario H, Schwarz K, Herter JM, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of a prospectively collected cohort of children and adolescents with polycythemia vera. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:622-626.

Gregg XT, Prchal JT. Recent advances in the molecular biology of congenital polycythemias and polycythemia vera. Curr Hematol Rep. 2005;4:238-242.

Klippel S, Strunck E, Temprinac S, et al. Quantification of PRV-1 mRNA distinguishes polycythemia vera from secondary erythrocytosis. Blood. 2003;102:3569-3574.

Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, et al. A gain of function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1779-1790.

Kwaan HC, Wang I. Hyperviscosity in polycythemia vera and other red cell abnormalities. Semin Thromb Hemostasis. 2003;29:451-458.

Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. The complete evaluation of erythrocytosis: congenital and acquired. Leukemia. 2009;23:834-844.

Schaefer AI. Molecular basis of the diagnosis and treatment of polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2006;107:4214-4222.

Spivak JL. Polycythemia vera: myths, mechanisms, and management. Blood. 2002;100:4272-4290.

Teofili L, Foa R, Giona F, et al. Childhood polycythemia vera and essential thrombocytopenia: does their pathogenesis overlap with that of adult patients? Haematologica. 2008;93:169-172.

Teofili L, Giona F, Martini M, et al. Markers of myeloproliferative diseases in childhood polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1048-1053.