Chapter 548 Vulvovaginal and Müllerian Anomalies

The sequence of events that occur in a developing embryo and early fetus to create a normal reproductive system includes cellular differentiation, duct elongation, fusion, resorption, canalization, and programmed cell death. Any of these processes can be interrupted during formation of the reproductive system, creating gonadal, müllerian, and/or vulvovaginal anomalies (see Table 548-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com). Genetic, epigenetic, enzymatic, and environmental factors all have some role in the process (see Table 548-2 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com)![]() . Most clinicians use the standard classification system adopted by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (originally the American Fertility Society [AFS] classification). Others have proposed modified and more-detailed anatomic classification systems such as the modified AFS system or the VCUAM (vagina, cervix, uterus, and adnexa-associated malformation) system.

. Most clinicians use the standard classification system adopted by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (originally the American Fertility Society [AFS] classification). Others have proposed modified and more-detailed anatomic classification systems such as the modified AFS system or the VCUAM (vagina, cervix, uterus, and adnexa-associated malformation) system.

Table 548-1 COMMON MÜLLERIAN ANOMALIES

| ANOMALY | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Hydrocolpos | Accumulation of mucus or nonsanguineous fluid in the vagina |

| Hemihematometra | Atretic segment of vagina with menstrual fluid accumulation |

| Hydrosalpinx | Accumulation of serous fluid in the fallopian tube, often an end result of pyosalpinx |

| Didelphic uterus | Two cervices, each associated with one uterine horn |

| Bicornuate uterus | One cervix associated with two uterine horns |

| Unicornuate uterus | Result of failure of one müllerian duct to descend |

Table 548-2 HERITABLE DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH MÜLLERIAN ANOMALIES

| MODE OF INHERITANCE | DISORDER | ASSOCIATED MÜLLERIAN DEFECT |

|---|---|---|

| Autosomal dominant | Camptobrachydactyly | Longitudinal vaginal septa |

| Hand-foot-genital | Incomplete müllerian fusion | |

| Autosomal recessive | Kaufan-McCusick | Transverse vaginal septa |

| Johanson-Blizzard | Longitudinal vaginal septa | |

| Renal-genital-middle ear anomalies | Vaginal atresia | |

| Fraser syndrome | Incomplete müllerian fusion | |

| Uterine hernia syndrome | Persistent müllerian duct derivatives | |

| Polygenic/multifactorial | Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome | Müllerian aplasia |

| X linked | Uterine hernia syndrome | Persistent müllerian duct derivatives |

Embryology (Pathogenesis)

Phenotypic sexual differentiation, especially during formation of the vulvovaginal and müllerian systems, is determined from genetic (46,XX), gonadal, and hormonal influences (Chapter 576). The genetic sex of the embryo is determined at fertilization when the gamete pronuclei fuse. The primordial germ cells (oogonia or spermatogonia) migrate from the yolk sac to the gonadal ridges. The primitive gonads are indistinguishable until about the 7th wk of development. Gonadal development determines the progression or regression of the genital ducts and subsequent hormonal production and, thus, the external genitalia. Critical areas in the SRY region (sex-determining region on the Y chromosome) are believed to be the factors that drive the development of a testis from a primitive gonad as well as spermatogenesis. The testis begins to develop between 6 and 7 wk of gestation, first with Sertoli cells followed by Leydig cells, and testosterone production begins at about 8 wk of gestation. The genital tract begins to differentiate later than the gonads. The differentiation of the wolffian ducts begins with an increase in testosterone, and the local action of testosterone activates development of the epididymis, vas deferens, and seminal vesicle. Further male genital duct and external genital structures depend on the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT).

In a 46,XX embryo, female sexual differentiation occurs about 2 wk later than gonadal differentiation in the male. Because the ovaries develop prior to and separately from the müllerian ducts, females with müllerian ductal anomalies usually have normal ovaries and steroid hormone production. The regression of the wolffian ducts results from the lack of local gonadal testosterone production, and the persistence of the müllerian (or paramesonephric) ducts results from the absence of AMH (antimüllerian hormone or müllerian-inhibiting substance) production. The müllerian ducts continue to differentiate into the fallopian tubes, uterus, and upper vagina without interference from AMH. There are complex interactions among the mesonephric, paramesonephric, and metanephric ducts (the metanephros becomes the adult kidney) early in embryonic development, and normal development of the müllerian system depends on such interaction. If this process is interrupted, coexisting müllerian and renal anomalies are often discovered in the female patient at the time of evaluation. Differentiation along the female pathway is often referred to as the default pathway, but it is an extremely intricate process regulated by the absence, presence, or dosage compensation of numerous gene products (e.g., SRY, SF-1, WTI, SOX9, Wnt-4, GATA4, DAX-1, BMP4, HOX genes, etc.) and remains not entirely understood.

By 10 wk of gestation, the caudal portions of the müllerian ducts fuse together in the midline to form the uterus, cervix, and upper vagina, in a Y-shaped structure, with the open upper arms of the Y forming the primordial fallopian tubes. Initially the müllerian ducts are solid cords that gradually canalize as they grow along and cross the mesonephric ducts ventrally and fuse in the midline. The mesonephric ducts caudally open into the urogenital sinus, and the müllerian ducts contact the dorsal wall of the urogenital sinus, where proliferation of the cells at the point of contact form the müllerian tubercle. Cells between the müllerian tubercle and the urogenital sinus continue to proliferate, forming the vaginal plate. At the same time of the midline fusion of the müllerian ducts, the medial walls begin to degenerate and resorption occurs to form the central cavity of the uterovaginal canal. Uterine septal resorption is thought to occur in a caudal to cephalad direction and to be complete at approximately 20 wk of gestation. This theory has been scrutinized because some anomalies do not fit the standard classification system. It is possible that septal resorption starts at some point in the middle and proceeds in both directions. At about 16 wk of gestation the central cells of the vaginal plate desquamate and resorption occurs, forming the vaginal lumen. The lumen of the vagina is initially separated from the urogenital sinus by a thin hymenal membrane. The hymenal membrane undergoes central resorption and perforates before birth. The sequential steps in this intricate process could be interrupted at countless points along the pathway of differentiation.

Epidemiology

Müllerian anomalies can include abnormalities in portions or all of the fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, and vagina. True estimates of prevalence are difficult due to the varied presentations and asymptomatic nature of some of the anomalies. Imaging techniques have made significant contributions to uterovaginal anomaly diagnoses, which has increased reporting of anomalies and led to additional combinations of anomalies. Most estimate that müllerian anomalies are present in 2-4% of the female population. The incidence increases in women with a history of adverse pregnancy outcomes or infertility: 5-10% of infertile women undergoing hysterosalpingogram, 5-10% of women with recurrent pregnancy loss, and 25% or more of women with late miscarriages and/or preterm delivery have müllerian defects.

Clinical Manifestations

Vulvovaginal and müllerian anomalies can manifest at a variety of chronological time points during a female’s life: from infancy, through childhood and adolescence, and adulthood (see Table 548-1). The majority of external genitalia malformations manifest at birth, and often even subtle deviations from normal in either a male or female newborn warrant evaluation. Structural reproductive tract abnormalities can be seen at birth or can cluster at menarche or any time during a woman’s reproductive life. Some müllerian anomalies are asymptomatic, whereas others can cause gynecologic, obstetric, or infertility issues.

Clinical manifestations and treatments depend on the specific type of müllerian anomaly and are varied. There may be a pelvic mass, which may or may not be associated with symptoms. A mass bulging at the introitus or within the vagina indicates complete or partial outflow tract obstruction. An adolescent can present with pelvic pain either in association with primary amenorrhea or several months after the onset of menarche. Patients also may be asymptomatic until they present with miscarriage, pregnancy loss, or preterm delivery. When presentation is acutely symptomatic, emergency management may be required. Obstruction can result from a number of distinct anomalies including an imperforate hymen, transverse vaginal septum, and noncommunicating rudimentary horn. As menstrual fluid accumulates proximal to the obstruction, the resulting hematocolpos and hematometra cause cyclic pain or a pelvic mass.

Laboratory Findings

Several radiographic studies have been used, often in combination, to aid in diagnosis including ultrasound, hysterosalpingogram (HSG), sonohysterography (saline-infusion sonography), and MRI. Laparoscopy and hysteroscopy was the gold standard for evaluation of müllerian anomalies, but the new standard may be MRI due to its noninvasive, high-quality capabilities. MRI is the most sensitive and specific imaging technique used for evaluating müllerian anomalies because it can image nearly all reproductive structures, blood flow, external contours, junctional zone resolution on T2 weighted images, and associated renal and other associated anomalies. MRI also has a high correlation with surgical findings because of its multiplanar capabilities and high spatial resolution. Three-dimensional ultrasound (3D US) is another useful diagnostic tool and may be superior to traditional pelvic ultrasound and HSG. Evaluation of the external contour of the uterus is important for differentiating types of uterine anomalies. This often requires a combination of radiologic modalities for uterine cavity, external contour, and possible tubal patency. Diagnostic laparoscopy or hysteroscopy may be necessary depending on the presentation, but it is used less with the advancement of MRI and other imaging.

Diagnosis of müllerian anomalies should include a physical exam, pelvic ultrasound, possibly MRI, and renal and skeletal inspections for associated anomalies. Renal anomalies are noted in 30-40% and skeletal anomalies are associated in 10-15% of patients with müllerian anomalies. Unilateral renal agenesis occurs in 15% of patients. The most common skeletal anomalies are vertebral. Patients usually have a normal female karyotype (46,XX), but several familial segregations and gene mutations and/or abnormal karyotypes have been reported (see Table 548-2). About 5-8% of patients with congenital müllerian anomalies have abnormal karyotypes. Most malformations are sporadic, with a polygenic mechanism and multifactorial etiology.

Adolescent patients can present with acute obstruction of the outflow tract due to a müllerian anomaly, which requires emergency evaluation and surgical treatment. A small percentage of girls present with concomitant urinary retention due to an altered urethral angle or pressure on the sacral plexus. Urinary hesitancy and incomplete emptying symptoms may be present before abdominopelvic pain from the obstruction in a patient of any age.

Uterine Anomalies

Anomalous development of the uterus may be symmetric or asymmetric and/or obstructed or nonobstructed. Patients can present with primary amenorrhea or have either irregular or regular menstrual cycles. There may be an asymptomatic pelvic mass or dysmenorrhea. In adolescents and adults, pregnancy loss can cause the first suspicion of a uterine anomaly. Treatment is highly specific to the specific anomaly.

Septate Uterus

A uterine septum is the most common of all müllerian anomalies, accounting for just over half of all abnormalities, and it is the most common structural uterine anomaly. After the 2 müllerian ducts fuse in the midline, resorption must occur to unify the endometrial cavities; failure of this process results in some degree of uterine septum. It can vary in length from just below the fundus to beyond the cervix, depending on the amount of caudal resorption. A septate uterus has a normal external uterine contour, which is what distinguishes it from a bicornuate or didelphic uterus. An MRI can help delineate between a predominantly fibrous septum and a muscular or myometrial septum. Because the septum may be poorly vascularized, a septate uterus is the most significant anomaly associated with pregnancy loss, as well as other untoward pregnancy outcomes. Hysteroscopic metroplasty (septal excision) is generally recommended in the setting of a previous pregnancy loss. Controversy still exists regarding whether a woman should have such a surgical procedure without a previous pregnancy loss. The length of the septum might not correlate with the frequency or occurrence of untoward pregnancy outcomes. Differentiating precisely between bicornuate and septate uteri is extremely important to determine effective and safe treatment plans.

Bicornuate Uterus

Both müllerian ducts develop and elongate in this anomaly, but they do not completely fuse in the midline. The vagina and external cervix are normal, but the extent of division of the two endometrial cavities can vary depending on the extent of failed fusion between the cervix and the fundus. Bicornuate uteri are also associated with increased preterm labor and delivery, malpresentation, and miscarriage. This anomaly accounts for about 10-20% of müllerian anomalies and a significant percentage of uterine anomalies.

Unicornuate Uterus and Rudimentary Horns

A unicornuate uterus results from a normal creation of a fallopian tube, functional uterus, cervix and vagina from one müllerian duct. The other side fails to develop, resulting in either absence of the contralateral müllerian duct or a rudimentary horn. There is a 30-40% association of renal anomalies. If a rudimentary horn is identified, it is important to determine whether functional endometrium is present (usually with T2-weighted MRI images). About  of rudimentary horns are noncommunicating, some with a fibrous band connecting the 2 structures. Rudimentary horns can also communicate with the contralateral uterus. A fertilized ovum can implant and develop within a rudimentary horn. These pregnancies are incompatible with expectant gestation, and rupture of the horn could be life threatening. Rupture tends to occur at a later gestation than with an ectopic pregnancy, and hemorrhage is severe. Patients with rudimentary horns with functioning endometrium can also present with pain due to accumulating menses. Because the other horn has a normal outflow pathway, these patients present with pain, not primary amenorrhea. Pregnancies that arise in a unicornuate uterus are associated with increased preterm labor and delivery, malpresentation, and miscarriage.

of rudimentary horns are noncommunicating, some with a fibrous band connecting the 2 structures. Rudimentary horns can also communicate with the contralateral uterus. A fertilized ovum can implant and develop within a rudimentary horn. These pregnancies are incompatible with expectant gestation, and rupture of the horn could be life threatening. Rupture tends to occur at a later gestation than with an ectopic pregnancy, and hemorrhage is severe. Patients with rudimentary horns with functioning endometrium can also present with pain due to accumulating menses. Because the other horn has a normal outflow pathway, these patients present with pain, not primary amenorrhea. Pregnancies that arise in a unicornuate uterus are associated with increased preterm labor and delivery, malpresentation, and miscarriage.

Uterine Didelphys

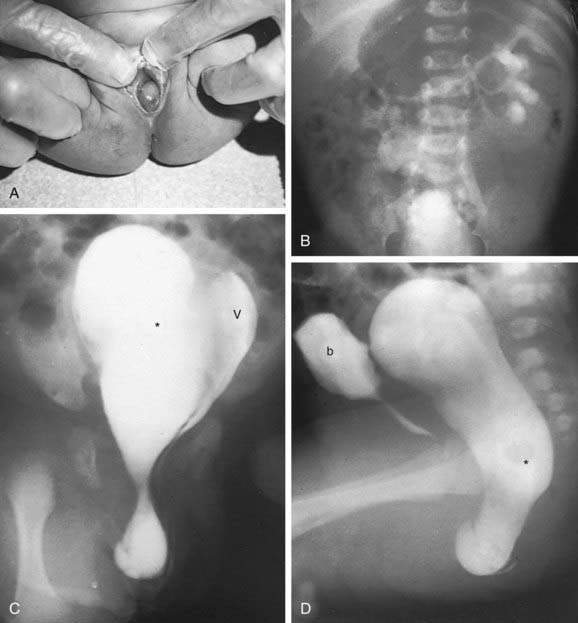

A uterine didelphys is the result a complete failure of fusion and represents 5% of müllerian anomalies. There are 2 fallopian tubes, 2 completely separate uterine cavities, 2 cervices, and often 2 vaginal canals or 2 partial canals because of an associated longitudinal vaginal septum (75% of the time). Evaluation for renal anomalies should be pursued because they are common as well. At times, the longitudinal septum attaches to 1 sidewall and obstructs 1 side of the vagina (or hemivagina). The combination of uterine didelphys, obstructed hemivagina, and ipsilateral renal agenesis is a variant of the broad spectrum of müllerian anomalies that is referred to as the Heryln-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome (HWWS) or obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly (OHVIRA) syndrome in the literature (Fig. 548-1). Adolescents with this disorder usually present with abdominal pain shortly after menarche. Although there still may be a risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes with a uterine didelphys (preterm labor, malpresentation), overall pregnancy outcomes are generally good and are associated with less risk than in other uterine anomalies.

Figure 548-1 Occluded right hemivagina and absent right kidney. A, A 2 day old girl presented with a gray cystic mass at the vaginal introitus. B, Intravenous urography shows no right renal function (probably absent kidney). In a cystogram (not shown), the bladder was displaced forward by the mass. The patent left hemivagina could be catheterized and was found to be markedly displaced to the left. On frontal (C) and lateral (D) vaginograms, contrast material introduced through a needle inserted in the cystic mass at the introitus opacifies a markedly distended right hemivagina and uterus (unilateral hydrometrocolpos) (asterisks). Contrast material from previous studies is still present in the patent vagina (V) and bladder (b).

(From Slovis TL, editor: Caffey’s pediatric diagnostic imaging, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2008, Mosby, p 2438.)

Arcuate Uterus

An arcuate uterus is a uterine cavity that has a small midline septum, from lack of a small amount of resorption, and sometimes a slight indentation of the uterine fundus. An arcuate uterus might represent a variant of normal rather than a müllerian anomaly. Untoward pregnancy outcomes are rare and surgical correction is not warranted.

Uterine Anomalies in DES-Exposed Patients

Intrauterine diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure is associated with an increased risk for development of uterine anomalies and clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix. DES was used to prevent preterm delivery, and this practice was discontinued in 1971. Commonly observed uterine features associated with DES exposure include a T-shaped uterus, cervical hypoplasia, fallopian tube irregularities, scalloped or irregularly shaped endometrial contour, constriction bands, and others. DES has been shown by several researchers to suppress and/or alter Wnt and HOX genes in mice, and thus might work by affecting gene expression in müllerian duct development, causing uterine abnormalities, vaginal adenosis, and potentially carcinoma.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the specific anomaly. Hysteroscopic surgical resection is widely supported for uterine septa. If a septate uterus extends through the cervical canal, many choose to leave this cervical portion of the septum due to concerns for future incompetence, although incisions have been done with uneventful follow-up in case reports. Most would support the incision of a uterine septum in the clinical setting of pregnancy loss, but some would also support prophylactic metroplasty without a history of miscarriage, especially before in vitro fertilization.

A noncommunicating horn with functional endometrium should be resected to improve quality of life or prevent future complications; opinions vary as to whether resection of a communicating horn or one with no functional endometrium is warranted. Any surgical resection of a rudimentary horn requires careful surgical technique to protect the ipsilateral ovarian blood supply and the myometrium of the remaining unicornuate uterus.

Although metroplasty had been advocated with didelphic and bicornuate uteri and a history of poor pregnancy outcomes in the past, currently most clinicians feel there is not enough evidence to support such a complicated procedure. Any obstruction to the outflow tract must also be relieved; this can necessitate creation of a vaginal window or excision of a hemivaginal septum.

Vaginal Anomalies

Abnormalities of the Hymen

An imperforate hymen is the most common obstructive anomaly, and familial occurrences have been reported. Its incidence is most often reported as approximately 1:1,000. In the newborn period and early infancy, it may be diagnosed by a bulging membrane due to a mucocolpos from maternal estrogen stimulation of the vaginal mucosa. This can eventually reabsorb if it is not too large or symptomatic. More often it is diagnosed at the time of menarche, when menstrual fluid accumulates. The clinical manifestations often are a bulging blue-black membrane, pain, primary amenorrhea, and normal secondary sex characters. Depending on the circumstance, patients might have cyclic abdominal pain or a pelvic mass. Other hymenal abnormalities have been reported. A normal hymen can have various configurations (annular, crescentic). Some hymenal membranes do not undergo complete resorption or perforation, resulting in microperforate, cribiform, or septate shaped hymen. Infants and children vary in age as to when these are recognized, but hymenal anomalies are often discovered after menarche when it is difficult for an adolescent to place a tampon

Congenital Absence of the Vagina and Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser Syndrome

Vaginal agenesis or atresia results when the vaginal plate fails to canalize. On physical exam it appears as an extremely foreshortened vagina, sometimes referred to as a vaginal dimple. Isolated (partial) vaginal agenesis involves an area of aplasia between the distal vaginal portion and a normal upper vagina, cervix, and uterus. On initial presentation it may be confused with a low transverse septum or imperforate hymen, and therefore clear delineation of the anomaly is critical before attempting surgical repair. It can also manifest with cyclic pain and a bulging mass just after menarche. Surgical repair and reconstruction are complicated and individualized and best performed with consultation of specialists.

Uterine and vaginal agenesis often occur together because of their close association during development, when müllerian ductal development fails early in the process. The most common cause of vaginal agenesis is Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome (MRKH), with an incidence reported at 1:4,000-10,000 female births. The cause is unknown and likely has a multigenetic and multifactorial etiology. MRKH is characterized by primary amenorrhea, normal vulva, anomalies of the uterus (usually aplasia or agenesis), attenuated fallopian tubes, normal ovaries, normal female karyotype and phenotype, and associated anomalies (most commonly renal and skeletal). The vagina either is completely absent or only has a small dimpled opening. MRI imaging is often necessary to determine if any small uterine remnant is present (often located on the pelvic sidewall or near the ovaries and only a small fibromuscular remnant) and to clearly delineate the anomaly. Absence of the vagina and uterus has significant anatomic, physiologic, and psychologic implications for the patient and family. Any diagnosis of müllerian agenesis must be differentiated from androgen insensitivity (testicular feminization) as well; karyotype, serum testosterone levels, and pubic hair distribution usually help distinguish the two.

Lesions involving other organ systems occur in association with the Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. The most common are urinary tract anomalies (15-40%) primarily involving unilateral absence of a kidney, a horseshoe or pelvic kidney, and skeletal anomalies (5-10%), which primarily involve vertebral development.

Longitudinal Vaginal Septa

Longitudinal vaginal septa represent failure of complete canalization of the vagina. These often occur in the presence of uterine anomalies as noted earlier.

Transverse Vaginal Septa (Vertical Fusion Defects)

Vertical fusion defects can result in a transverse septum, which may be imperforate and associated with hematocolpos or hematometra in adolescents or with mucocolpos in infants. These are much less common anomalies, reportedly found in 1:80,000 females. Most patients present with amenorrhea and cyclical pain around the time of menarche. Patients who have a small opening in the transverse septa might present with prolonged vaginal drainage and discharge. Transverse vaginal septa vary in location in the vagina (15-20% in the lower third, but most in the middle or upper third of the vagina) and thickness, but are generally ≤1 cm thick. High locations, thick septa, and narrow vaginal orifices present challenging surgical cases.

Transverse vaginal septa may be associated with other congenital anomalies, although this occurs less often than with müllerian agenesis. These patients have a functional normal uterus, unlike women with MRKH. There is also an increased incidence of endometriosis secondary to retrograde menstruation.

Evaluation of transverse vaginal septa includes careful pelvic examination and often pelvic imaging, usually with MRI and ultrasound, to delineate the anatomic abnormalities. MRI is especially helpful to determine the thickness of the septum and presence of a cervix and for surgical planning. Diagnosis and treatment plans should be made as soon as possible after menarche, because significant accumulation of hematometria and/or hematosalpinx could affect future reproductive success by negatively affecting uterine and/or tubal function.

Treatment

An imperforate hymen requires resection to prevent or relieve the outflow tract obstruction. Many approach it with a horizontal or cruciate incision, excision of excess tissue, and reanastomosis of the mucosal edges. Repair should be done at time of diagnosis, if the patient is symptomatic. Although the lesion may be repaired any time during infancy, childhood, or adolescence, surgery is facilitated by estrogen stimulation and thus is ideally performed in adolescence, either after puberty or menarche.

Treatment of congenital absence of the vagina is usually delayed until the patient is ready to be sexually active. The nonsurgical approach is the most common first-line therapy due to the high success rate and extremely low morbidity. It requires dedicated use of dilators to create a functional vagina. The series of dilators come in progressively increasing sizes and require a commitment and maturity on the part of the patient to comply with daily use (20-30 min daily). If done correctly it is possible to achieve a functional vaginal length (6-8 cm), width, and physiologic angle for intercourse in about 6-8 wk of therapy. When the ultimate size that accommodates coitus is reached, then the patient must use the dilator or have coitus with a frequency that maintains adequate length.

Surgical approaches require more expertise and often some postoperative vaginal dilation to ensure a functional result. Controversy exists among surgical subspecialties, because pediatric surgeons and pediatric urologists often recommend creating the neovagina in infancy. Pediatric gynecologists and reproductive endocrinologists believe better outcomes result from creating the neovagina when the young woman is interested in sexual activity and can participate in the decision to have surgery and in her own postoperative recovery. There is no consensus as to the best surgical option; the most-used procedures include 2 surgical approaches followed by dilators or an approach using a loop of bowel out of which to construct a vagina. Patients need to be counseled about the ability to use their own oocytes and a gestational carrier through IVF to achieve pregnancy. These therapies can be quite complicated physically and emotionally. They are best approached in a multidisciplinary fashion, often with the assistance of psychologic counseling and surgeons with specialized training.

For transverse vaginal septa, treatment is surgical resection of the obstruction through a vaginal approach. Some surgeons advocate waiting ≥1 menstrual cycles or using preoperative dilators from below to increase the depth and circumference of the distal vagina and to allow menstrual blood to accumulate and dilate the upper portion of the vagina. Complete resection of the septum, with primary anastomosis of the upper and lower mucosal segments, should be attempted. A vaginal stent is sometimes placed postoperatively in the vagina to maintain patency and allow squamous epithelization of the upper vagina and cervix. Follow-up dilation may be necessary after the stent is removed. Careful preoperative assessment is important because surgeons who begin a case believing they are operating on an imperforate hymen can find themselves in entirely different and more complex surgical planes. Regardless of the approach, vaginoplasty is often best deferred until the patient is mature and physically and psychologically prepared to participate in the healing process and postoperative dilator treatments.

Longitudinal vaginal septa themselves do not lead to adverse reproductive outcomes but may be symptomatic in a patient, causing dyspareunia, difficulties with tampon insertion, or impedance during vaginal birth. Such complaints can warrant a resection of the vaginal septa. In a small number of patients there may be unilateral obstruction of a hemivagina, which would require incision and resection.

Cervical Anomalies

Congenital atresia or complete agenesis of the uterine cervix is extremely rare and often manifests at puberty with amenorrhea and pelvic pain. It is associated with significant renal anomalies in 5-10% of patients. A pelvic MRI is often warranted to completely define the abnormality. Usually, pain and obstruction are significant and a hysterectomy is necessary. Attempts to reconnect the uterus to the vagina are rarely successful and associated with significant morbidity and reoperation rates. As with most müllerian anomalies, the ovaries usually remain normal and future reproduction can still occur through the use of IVF and a gestational carrier.

Vulvar and Other Anomalies

Complete Vulvar Duplication

Duplication of the vulva is a rare congenital anomaly that is seen in infancy and consists of 2 vulvas, 2 vaginas, and 2 bladders, a didelphic uterus, a single rectum and anus, and 2 renal systems.

Labial Asymmetry and Hypertrophy

With the onset of puberty the labia minora enlarge and grow to an adult size. A woman’s labia can vary in size and shape. Asymmetry of the labia, where the right and left labia are different in size and appearance, is a normal variant. Some women are uncomfortable with what they perceive to be their asymmetric or enlarged labia minora and complain about self-consciousness and discomfort while wearing tight clothing, exercising, or having sex. The enlarged labia can have a protuberant and abnormal appearance that can be functionally or psychologically bothersome. Local irritation, problems of personal hygiene with bowel movements or menses, interference with sexual intercourse or while sitting or exercising have resulted in requests for labial reduction. Some surgeons are advertising procedures to reduce uneven or enlarged labia minora. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not support performing such surgery unless there is significant impairment in function. Medically indicated surgical procedures can include reversal or repair of female genital cutting and treatment for labial hypertrophy or asymmetrical labial growth secondary to congenital conditions, chronic irritation, or excessive androgenic hormones. Complications of labial surgery include loss of sensation, keloid formation, and dyspareunia.

Clitoral Abnormalities

Agenesis of the clitoris is rare. Clitoral duplication has been reported, often associated with pelvic organ abnormalities, including agenesis of other genital tract structures and bladder exstrophy.

Cloacal Anomalies

Cloacal anomalies are rare lesions representing a common urogenital sinus into which the gastrointestinal, urinary, and vaginal canals all exit. Usually there is an abnormality in all or some of the processes of fusion of the müllerian ducts, development of the sinovaginal bulbs, or development of the vaginal plate. The single opening (cloaca) requires surgical correction, preferably by a multidisciplinary pediatric surgical team.

Ductal Remnants

Even though the opposite duct regresses in both sexes, there can sometimes be a small portion of either the müllerian or wolffian duct that remains in either the male or female, respectively. Such remnants can form cysts, which is what makes them clinically visible during surgery, examination, or imaging. Most do not cause pain, although torsion of some has been reported, and small asymptomatic ones usually do not require resection. The most commonly reported are hydatid of Morgagni cysts (remnant of a wolffian duct arising from the fallopian tube), cysts of the broad ligament, and Gartner’s duct cysts, which can form an ectopic ureter or be found along the cervix or vaginal walls.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Endometriosis in adolescents. ACOG committee opinion no. 310. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:921-927.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Vaginal “rejuvenation” and cosmetic vaginal procedures. ACOG committee opinion no. 378. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:737-738.

American Society for Reproductive Medicine. The American Fertility Society classification of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988;49:944-955.

Deutch TD, Abuhamad AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of müllerian duct anomalies. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:413-423.

Gell JS. Müllerian anomalies. Semin Reprod Med. 2003;21:375-388.

Laufer MR, Goldstein DP, Hendren WH. Structural abnormalities of the female reproductive tract. In: Emans SJ, Laufer MR, Goldstein DP, editors. Pediatric and adolescent gynecology. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:334-416.

MacLaughlin DT, Donahoe PK. Sex determination and differentiation. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:367-378.

Miller RJ, Breech LL. Surgical correction of vaginal anomalies. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:223-236.

Olpin JD, Heilbrun M. Imaging of müllerian duct anomalies. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52:40-56.

Oppelt P, Renner SP, Brucker S, et al. The VCUAM (vagina cervix uterus adnexa-associated malformation) classification; a new classification for genital malformations. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1493-1497.

Rackow BW, Arici A. Reproductive performance of women with müllerian anomalies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:229-237.

Salim R, Woelfer B, Backos M, et al. Reproducibility of three-dimensional ultrasound diagnosis of congenital uterine anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21:578-582.

Shulman LP. Müllerian anomalies. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:214-222.

Taylor E, Gomel V. The uterus and fertility. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1-16.