Chapter 597 Pseudotumor Cerebri

Pseudotumor cerebri, also known as idiopathic intracranial hypertension, is a clinical syndrome that mimics brain tumors and is characterized by increased intracranial pressure (ICP; >200 mm H2O in infants and >250 mm H2O in children), with a normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cell count and protein content and normal ventricular size, anatomy, and position documented by MRI. Papilledema is universally present in children old enough to have a closed fontanel.

Etiology

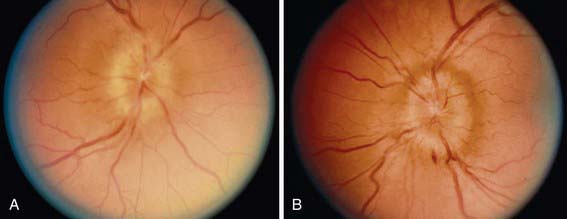

Table 597-1 lists the many causes of pseudotumor cerebri. There are many explanations for the development of pseudotumor cerebri, including alterations in CSF absorption and production, cerebral edema, abnormalities in vasomotor control and cerebral blood flow, and venous obstruction. The causes of pseudotumor are numerous and include metabolic disorders (galactosemia, hypoparathyroidism, pseudohypoparathyroidism, hypophosphatasia, prolonged corticosteroid therapy or rapid corticosteroid withdrawal, possibly growth hormone treatment, refeeding of a significantly malnourished child, hypervitaminosis A, severe vitamin A deficiency, Addison disease, obesity, menarche, oral contraceptives, and pregnancy), infections (roseola infantum, sinusitis, chronic otitis media and mastoiditis, Guillain-Barré syndrome), drugs (nalidixic acid, doxycycline, minocycline, tetracycline, nitrofurantoin), isotretinoin used for acne therapy especially when combined with tetracycline, hematologic disorders (polycythemia, hemolytic and iron-deficiency anemias [Fig. 597-1], Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome), obstruction of intracranial drainage by venous thrombosis (lateral sinus or posterior sagittal sinus thrombosis), head injury, and obstruction of the superior vena cava. When a cause is not identified, the condition is classified as idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

Clinical Manifestations

The most frequent symptom is headache, and although vomiting also occurs; the vomiting is rarely as persistent and insidious as that associated with a posterior fossa tumor. Transient visual obscuration and diplopia (secondary to dysfunction of the abducens nerve) may also occur. Most patients are alert and lack constitutional symptoms. Examination of the infant with pseudotumor cerebri characteristically reveals a bulging fontanel and a “cracked pot sound” or MacEwen sign (percussion of the skull produces a resonant sound) due to separation of the cranial sutures. Papilledema with an enlarged blind spot is the most consistent sign in a child beyond infancy. Papilledema may be absent or mild in infants with pseudotumor cerebri because high CSF pressure may be transmitted to the soft fontanels earlier than the optic nerves. Early optic nerve edema may be noted with orbit ultrasonography. An inferior nasal visual field defect may be detected on formal tangent screen testing. The presence of focal neurologic signs should prompt an investigation to uncover a process other than pseudotumor cerebri. Any patient suspected of pseudotumor cerebri should undergo an MRI. MRA/MRV should be considered in patients suspected of dural sinus thrombosis.

Treatment

The key objective in management is recognition and treatment of the underlying cause. There are no randomized clinical trials to guide the treatment of pseudotumor cerebri. Pseudotumor cerebri can be a self-limited condition, but optic atrophy and blindness are the most significant complications of untreated pseudotumor cerebri. The obese patient should be treated with a weight loss regimen, and if a drug is thought to be responsible, it should be discontinued. For most patients old enough to participate in such testing, serial monitoring of visual function is required. Serial determination of visual acuity, color vision, and visual fields is critical in this disease. Serial optic nerve examination is essential as well. Serial visual-evoked potentials are useful if the visual acuity cannot be reliably documented. The initial lumbar tap that follows a CT or MRI scan is diagnostic and may be therapeutic. The spinal needle produces a small rent in the dura that allows CSF to escape the subarachnoid space, thus reducing the ICP. Several additional lumbar taps and the removal of sufficient CSF to reduce the opening pressure by 50% occasionally lead to resolution of the process. Acetazolamide, 10-30 mg/kg/24 hr, is an effective regimen. Corticosteroids are not routinely administered, although they may be used in a patient with severe ICP elevation who is at risk of losing visual function and is awaiting a surgical decompression. Sinus thrombosis is typically addressed by anticoagulation therapy. Rarely, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt or subtemporal decompression is necessary, if the aforementioned approaches are unsuccessful and optic nerve atrophy supervenes. Some centers perform optic nerve sheath fenestration to prevent visual loss. Any patient whose ICP proves to be refractory to treatment warrants consideration for repeat neuroradiologic studies. A slow-growing tumor or obstruction of a venous sinus may become evident by the time of reinvestigation.

Abu-Serieh B, Ghassempour K, Duprez T, et al. Stereotactic ventriculoperitoneal shunting for refractory idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(6):1039-1043.

Acheson JF. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension and visual function. Br Med Bull. 2006;79–80:233-244.

Bruce BB, Preechawat P, Newman NJ, et al. Racial differences in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2008;70(11):861-867.

Dirge KB. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. BMJ. 2010;341:109-110.

Distelmaier F, Sengler U, Messing-Juenger M, et al. Pseudotumor cerebri as an important differential diagnosis of papilledema in children. Brain Dev. 2006;28(3):190-195.

Friedman DI. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2007;11(1):62-99.

Friedman DI. Pseudotumor cerebri. Neurol Clin. 2004;22(1):99-131.

Goyal S, Krishnamoorthy K, Noviski N, et al. What’s new in childhood idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neuroophthalmology. 2009;33:23-35.

Kesler A, Bassan H. Pseudotumor cerebri—idiopathic intracranial hypertension in the pediatric population. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2006;3(4):387-392.

Matthews YY. Drugs used in childhood idiopathic or benign intracranial hypertension. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2008;93(1):19-25.

Mercille G, Ospina LH. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a review. Pediatr Rev. 2007;28(11):e77-86.

Rangwala LM, Liu GT. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(6):597-617.

Thuente DD, Buckley EG. Pediatric optic nerve sheath decompression. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(4):724-727.