Chapter 649 Diseases of the Epidermis

649.1 Psoriasis

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Psoriasis is characterized by proliferation and abnormal differentiation of keratinocytes and inflammatory cell infiltration of the epidermis and dermis secondary to a primary T-cell abnormality. Psoriasis has a complex multifactorial genetic basis. The major psoriasis-susceptibility gene (PSORS1) is HLA-CW*0602. Numerous other psoriasis susceptibility genes have been identified (PSORS2-PSORS9). Interleukins IL12B and IL23R are the most compelling gene products involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.

Clinical Manifestations

This common, chronic skin disorder is first evident in ≈ 30% of affected individuals within the first 2 decades of life. The lesions consist of erythematous papules that coalesce to form plaques with sharply demarcated, irregular borders. If they are unaltered by treatment, a thick silvery or yellow-white scale (resembling mica) develops (Fig. 649-1A). Removal of the scale may result in pinpoint bleeding (Auspitz sign). The Koebner, or isomorphic, response, in which new lesions appear at sites of trauma, is a valuable diagnostic feature. Lesions may occur anywhere, but preferred sites are the scalp, knees, elbows, umbilicus, superior intergluteal fold, and genitals. Small raindrop-like lesions on the face are common. Nail involvement, a valuable diagnostic sign, is characterized by pitting of the nail plate, detachment of the plate (onycholysis), yellowish brown subungual discoloration, and accumulation of subungual debris (Fig. 649-1B).

Figure 649-1 A, Chronic psoriatic plaques. B, Psoriatic nail dystrophy. C, Guttate psoriasis in widespread distribution over the trunk.

Psoriasis is rare in neonates but may be severe and recalcitrant and may pose a diagnostic problem. Other rare forms include psoriatic erythroderma, localized or generalized pustular psoriasis, and linear psoriasis.

Guttate psoriasis, a variant that occurs predominantly in children, is characterized by an explosive eruption of profuse, small, oval or round lesions that morphologically are identical to the larger plaques of psoriasis (Fig. 649-1C). Sites of predilection are the trunk, face, and proximal portions of the limbs. The onset frequently follows a streptococcal infection; a culture of the throat and serologic titers should be obtained. Guttate psoriasis has also been observed after perianal streptococcal infection, viral infections, sunburn, and withdrawal of systemic corticosteroid therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

Psoriasis is a clinical diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of plaque-type psoriasis includes nummular dermatitis, tinea corporis, seborrheic dermatitis, postinfectious arthritis syndromes, pityriasis rosea, pityriasis lichenoides, and pityriasis rubra pilaris. Scalp lesions may be confused with seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, or tinea capitis. Diaper area psoriasis may mimic seborrheic dermatitis, eczematous diaper dermatitis, perianal streptococcal disease, or candidosis. Guttate psoriasis can be confused with viral exanthems, secondary syphilis, pityriasis rosea, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC). Nail psoriasis must be differentiated from onychomycosis, lichen planus, and onychodystrophy.

Pathology

When the diagnosis is in doubt, histopathologic examination of an untreated lesion reveals characteristic changes of psoriasis, demonstrating hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, elongated rete ridges, neutrophilic infiltrate in the epidermis, and lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis.

Treatment

The therapeutic approach varies with the age of the child, type of psoriasis, sites of involvement, and extent of the disease. Physical and chemical trauma to the skin should be avoided as much as possible (see previous discussion of Koebner response).

The treatment of psoriasis should be viewed as a 4-tier process. The 1st tier is topical therapy. Topical corticosteroid preparations are effective. Mid-potency or stronger topical steroids are necessary (Chapter 638). The preparation that is least potent but effective should be applied twice a day. The topical vitamin D analog calcipotriene is also effective. Calcipotriene can burn and sting, limiting its usefulness in children. One commonly used strategy is to use calcipotriene twice a day on weekdays and a high- to super-potency topical steroid twice a day on weekends. Tazarotene, a topical retinoid, is also useful. It may be used alone or in combination with other topical modalities. Tar preparation and anthralin may also be used. For scalp lesions, applications of a phenol and saline solution (e.g., Baker Cummins P & S Liquid) followed by a tar shampoo are effective in the removal of scales. A high- to super-potency corticosteroid in a foam, solution, lotion, or gel base may be applied when the scaling is diminished. Nail lesions are difficult to treat but may respond to topical tazarotene.

The 2nd tier of therapy is phototherapy. Narrow-band ultraviolet B (UVB 311 nm; NB-UVB) irradiation is the primary form of UVB therapy used in childhood. It is as or nearly as effective as psoralen with UVA (PUVA), without the side effects associated with psoralen. If available, phototherapy should be used for children with extensive disease in whom topical therapy has failed. Excimer (308-nm) laser UVB irradiation may be used for localized treatment-resistant plaques. These treatments are time consuming and available only at limited locations.

The 3rd tier is systemic therapy. A few children with severe psoriasis require systemic therapy. Methotrexate (0.2 to 0.4 mL/kg once a week), oral retinoids (0.3 to 1.0 mg/kg/day), and cyclosporine (3-5 mg/kg/day) are used for the rare severe and generalized forms of psoriasis. Oral retinoids may be combined with phototherapy.

The 4th tier of therapy is the biologic response modifiers, including the tumor necrosis factor inhibitors etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab and the T-cell function inhibitors efalizumab and alefacept. Ustekinumab, a human monoclonal antibody that prevents interactions between interleukins IL-12 and IL-23 and their cell surface receptor, has efficacy in treating moderate to severe chronic psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Prognosis

Prognosis is best for children with limited disease. Psoriasis is a lifelong disease characterized by remissions and exacerbations. Arthritis may be an extracutaneous complication.

Anstey A. Home UVB phototherapy for psoriasis. BMJ. 2009;338:1153-1154.

Bartlett BL, Tyring SK. Ustekinumab for chronic plaque psoriasis. Lancet. 2008;371:1639-1640.

Benoit S, Hamm H. Childhood psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:555-562.

Boehncke WH, Boehncke S, Schön MP. Managing comorbid disease in patients with psoriasis. BMJ. 2010;340:200-203.

Burden AD, Boon MH, Leman J, et al. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in adults: summary of SIGN guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:c5623.

Cuchacovich RS, Espinoza LR. Ustekinumab for psoriatic arthritis. Lancet. 2009;373:605-606.

Duffin KC, Chandran V, Gladman DD, et al. Genetics of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: update and future direction. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1449-1453.

Griffiths CEM, Strober BE, van de Kerkhof P, et al. Comparison of ustekinumab and etanercept for moderate to severe psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(2):118-128.

Kimball AB, Kupper TS. Future perspectives/quo vadis psoriasis treatment? Immunology, pharmacogenomics, and epidemiology. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:554-561.

Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496-508.

Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Langley RG, et al. Etanercept treatment for children and adolescents with plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:241-251.

649.2 Pityriasis Lichenoides

Pityriasis lichenoides encompasses pityriasis lichenoides acuta (PLA; pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta [PLEVA] and Mucha-Habermann disease) and PLC. The designation of pityriasis lichenoides as acute or chronic refers to the morphologic appearance of the lesions rather than to the duration of the disease. No correlation is found between the type of lesion at the onset of the eruption and the duration of the disease. Many patients have both acute and chronic lesions simultaneously, and transition of lesions from one form into another occurs occasionally. A rare variant, acute febrile ulcernecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease, is also included in the spectrum of pityriasis lichenoides.

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Two main theories exist for the etiology of pityriasis lichenoides. The first is that it arises in a genetically susceptible individual from an atypical immune response to a foreign antigen. The second is that it represents a monoclonal T-cell lymphocytic proliferation on the pathway to cutaneous T-cell dyscrasia.

Clinical Manifestations

Pityriasis lichenoides most commonly manifests in the second and third decades of life; 30% of cases manifest before age 20 yr.

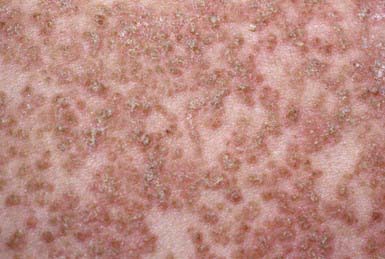

PLC manifests as generalized, multiple, 3- to 5-mm brown-red papules that are covered by a fine grayish scale (Fig. 649-2). Lesions may be asymptomatic or may cause minimal pruritus and occasionally become vesicular, hemorrhagic, crusted, or superinfected. Individual papules become flat and brownish in 2-6 wk, ultimately leaving a hyperpigmented or hypopigmented macule. Scarring is unusual. Lesions are most common on the trunk and extremities and generally spare the face, palmoplantar surfaces, scalp, and mucous membranes.

PLA manifests as an abrupt eruption of numerous papules that have a vesiculopustular and then a purpuric center, are covered by a dark adherent crust, and are surrounded by an erythematous halo (Fig. 649-3). Constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, headache, and arthralgias may be present for 2-3 days after the initial outbreak. Lesions are distributed diffusely on the trunk and extremities, as in PLC. Individual lesions heal within a few weeks, sometimes leaving a varioliform scar, and successive crops of papules produce the characteristic polymorphous appearance of the eruption, with lesions in various stages of evolution. The overall eruption persists for months to years.

Acute febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease manifests as fever and ulceronecrotic plaques up to 1 cm in diameter, which are most common on the anterior trunk and flexors of the proximal upper extremities. Arthritis and superinfection of cutaneous lesions with Staphylococcus aureus may also develop. The ulceronecrotic lesions heal with hypopigmented scarring in a few weeks.

Pathology

PLC histologically shows a parakeratotic, thickened corneal layer; epidermal spongiosis; a superficial perivascular infiltrate of macrophages and predominantly CD8 lymphocytes that may extend into the epidermis; and small numbers of extravasated erythrocytes in the papillary dermis.

The histopathologic changes of PLA reflect its more severe nature. Intercellular and intracellular edema in the epidermis may lead to degeneration of keratinocytes. A dense perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate that extends upward into the epidermis and downward into the reticular dermis, endothelial cell swelling, and extravasation of erythrocytes into the epidermis and dermis are additional characteristic features. The histology of acute febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease is similar to that of PLA, with leukocytoclastic vasculitis occasionally seen.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of pityriasis lichenoides includes guttate psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, drug eruptions, secondary syphilis, viral exanthems, and lichen planus. The chronicity of pityriasis lichenoides helps preclude pityriasis rosea, viral exanthems, and some drug eruptions. A skin biopsy helps distinguish pityriasis lichenoides from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

Treatment

In general, pityriasis lichenoides should be considered a benign condition that does not alter the health of the child. A lubricant to remove excessive scaling may be all that is necessary if the patient is asymptomatic. Topical steroids may help the pruritus but do not alter the course of the disease. Some children may benefit from treatment with erythromycin (30-50 mg/kg/24hr for 2 mo). Natural sunlight is also helpful. NB-UVB is the treatment of choice for widespread, pruritic disease. The rare febrile ulceronecrotic form may require systemic corticosteroids, other systemic immunosuppressives or anti–tumor necrosis factor or anti–T cell biologic response modifiers.

Khachemoune A, Biyumin ML. Pityriasis lichenoides: pathophysiology, classification, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:29-36.

Sotiriou E, Patsatsi A, Tsorova C, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: a case report and review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:350-355.

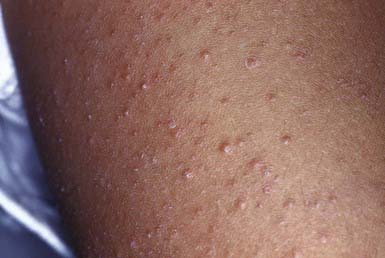

649.3 Keratosis Pilaris

Keratosis pilaris is a common papular eruption that may vary in extent from sparse lesions over the extensor aspects of the limbs to involvement of most of the body surface; typical areas of involvement include the upper extensor surface of the arms and the thighs, cheeks, and buttocks. The lesions may resemble gooseflesh; they are noninflammatory, scaly, follicular papules that do not coalesce. Irritation of the follicular plugs occasionally causes erythema surrounding the keratotic papules (Fig. 649-4). A subset of patients have keratosis pilaris associated with facial telangiectasia and ulerythema ophryogenes, a rare cutaneous disorder characterized by inflammatory keratotic facial papules that may result in scars, atrophy, and alopecia. Because the lesions of keratosis pilaris are associated with and accentuated by dry skin, they are often more prominent during the winter. They are more frequent in patients with atopic dermatitis and are most common during childhood and early adulthood, tending to subside in the 3rd decade of life. Mild or localized eruptions are treated with lubrication with a bland emollient; more pronounced or widespread lesions require regular applications of a 10-40% urea cream or an α-hydroxy acid preparation such as 12% lactic acid cream or lotion. Therapy may improve the condition but does not cure it.

649.4 Lichen Spinulosus

Lichen spinulosus is an uncommon disorder that occurs principally in children and more frequently in boys. The cause is unknown. The lesions consist of sharply circumscribed irregular plaques of spiny, keratinous projections that protrude from the orifices of the pilosebaceous canals. Plaques may occur anywhere on the body and are often distributed symmetrically on the trunk, elbows, knees, and extensor surfaces of the limbs. Although sometimes erythematous, the lesions are usually skin colored. They are readily palpable and represent keratotic follicular plugs. Lichen spinulosus is easily differentiated from keratosis pilaris because the latter lesions are never grouped to form plaques. More commonly, lichen spinulosus is confused with papular eczema.

Treatment is usually unnecessary. For patients who regard the eruption as a cosmetic defect, urea-containing lubricants (10-40%) are often effective in flattening the projections. Tretinoin gel and hydroactive adhesives may also be used. The plaques usually disappear spontaneously after several months or years.

649.5 Pityriasis Rosea

Etiology/Pathogenesis

The cause of pityriasis rosea is unknown; a viral agent is suspected, and there is debate over the role of human herpesviruses 6 and 7 in this condition.

Clinical Manifestations

This benign, common eruption occurs most frequently in children and young adults. Although a prodrome of fever, malaise, arthralgia, and pharyngitis may precede the eruption, children rarely complain of such symptoms. A herald patch, a solitary, round or oval lesion that may occur anywhere on the body and is often but not always identifiable from its large size, usually precedes the generalized eruption. Herald patches vary from 1 to 10 cm in diameter; they are annular in configuration and have a raised border with fine, adherent scales. Approximately 5-10 days after the appearance of the herald patch, a widespread, symmetric eruption involving mainly the trunk and proximal limbs becomes evident (Fig. 649-5). When the disease is extensive, the face, scalp, and distal limbs may be involved; in the inverse form of pityriasis rosea, only those sites may be affected. Lesions may appear in crops for several days. Typical lesions are oval or round, <1 cm in diameter, slightly raised, and pink to brown. The developed lesion is covered by a fine scale, which gives the skin a crinkly appearance. Some lesions clear centrally and produce a collarette of scale that is attached only at the periphery. Papular, vesicular, urticarial, hemorrhagic, and large annular lesions are unusual variants. The long axis of each lesion is usually aligned with the cutaneous cleavage lines, a feature that creates the so-called Christmas tree pattern on the back. Conformation to skin lines is often more discernible in the anterior and posterior axillary folds and supraclavicular areas. Duration of the eruption varies from 2 to 12 wk. The lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly to severely pruritic.

Differential Diagnosis

The herald patch may be mistaken for tinea corporis, a pitfall that can be avoided if microscopic evaluation of a potassium hydroxide preparation of scrapings of the lesion is performed. The generalized eruption resembles a number of other diseases; secondary syphilis is the most important. Drug eruptions, viral exanthems, guttate psoriasis, PLC, and nummular dermatitis can also be confused with pityriasis rosea.

Treatment

Therapy is unnecessary for asymptomatic patients with pityriasis rosea. If scaling is prominent, a bland emollient may suffice. Pruritus may be suppressed by a lubricating lotion containing menthol and camphor or by an oral antihistamine for sedation, particularly at night, when itching may be troublesome. Occasionally, a mid-potency topical corticosteroid preparation may be necessary to alleviate pruritus. After the eruption has resolved, postinflammatory hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation may be pronounced, particularly in dark-skinned patients. These changes disappear in subsequent weeks to months.

Amer A, Fischer H, Li X. The natural history of pityriasis rosea in black American children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:503-506.

Browning JC. An update on pityriasis rosea and other similar childhood exanthems. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:481-485.

Gonzalez LM, Allen R, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA. Pityriasis rosea: an important papulosquamous disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:757-764.

649.6 Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris

Etiology

The cause of pityriasis rubra pilaris is unknown. Although a genetic form with autosomal dominant transmission may account for some cases in childhood, most cases are sporadic.

Clinical Manifestations

This rare chronic dermatosis often has an insidious onset with diffuse scaling and erythema of the scalp, which is indistinguishable from the findings in seborrheic dermatitis, and with thick hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles (Fig. 649-6A). Lesions over the elbows and knees are also common (Fig. 649-6B). The characteristic primary lesion is a firm, dome-shaped, tiny, acuminate papule, which is pink to red and has a central keratotic plug pierced by a vellus hair. Masses of these papules coalesce to form large, erythematous, sharply demarcated orangish plaques, within which islands of normal skin can be distinguished, creating a bizarre effect. Typical papules on the dorsum of the proximal phalanges are readily palpated. Gray plaques or papules resembling lichen planus may be found in the oral cavity. Dystrophic changes in the nails may occur and mimic those of psoriasis.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes ichthyosis, seborrheic dermatitis, keratoderma of the palms and soles, and psoriasis.

Histology

Skin biopsy revealing follicular plugging, parakeratotic, perifollicular shoulder, and checkerboard pattern of orthokeratosis and hypogranulosis may differentiate this condition from psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis.

Treatment

The numerous therapeutic regimens recommended are difficult to evaluate because pityriasis rubra pilaris has a capricious course with exacerbations and remissions. Lubrication alone is useful in mild cases. Topical and oral retinoids (1 mg/kg/day) have been used most frequently. In childhood, the prognosis for eventual resolution is relatively good.

649.7 Darier Disease (Keratosis Follicularis)

Etiology

A rare genetic disorder, Darier disease is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait (ATP2A2 gene).

Clinical Manifestations

Onset usually occurs in late childhood. Typical lesions are small, firm, skin-colored papules that are not always follicular in location. The lesions eventually acquire yellow malodorous crusts; coalesce to form large, gray-brown, vegetative plaques (Fig. 649-7); and usually involve the face, neck, shoulders, chest, back, and limb flexures in a symmetric distribution. Papules, fissures, crusts, and ulcers may appear on the mucous membranes of the lips, tongue, buccal mucosa, pharynx, larynx, and vulva. Hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles and nail dystrophy with subungual hyperkeratosis are variable features. Severe pruritus, secondary infection, offensive odor, and aggravation of the dermatosis on exposure to sunlight may occur.

Histology

Histologic changes seen in Darier disease are diagnostic: hyperkeratosis, intraepidermal separation with formation of suprabasal clefts, and dyskeratotic epidermal cells are characteristic features.

Differential Diagnosis

Darier disease is most likely to be confused with seborrheic dermatitis or flat warts.

Treatment

Treatment is nonspecific. Some cases respond to topical retinoic acid, with or without occlusive dressings. Severe disease may be controlled with oral retinoids (1 mg/kg/day). Secondary infection may require local cleansing and systemically administered antibiotics. Affected individuals usually suffer more during the summer.

649.8 Lichen Nitidus

Clinical Manifestations

This chronic, benign, papular eruption is characterized by minute (1-2 mm), flat-topped, shiny, firm papules of uniform size. The papules are most often skin colored but may be pink or red. In black individuals, they are usually hypopigmented (Fig. 649-8). Sites of predilection are the genitals, abdomen, chest, forearms, wrists, and inner aspects of the thighs. The lesions may be sparse or numerous and may form large plaques; careful examination usually discloses linear papules in a line of scratch (Koebner phenomenon), a valuable clue to the diagnosis because it occurs in only a few diseases. Lichen nitidus occurs in all age groups. The cause is unknown. Patients with lichen nitidus are usually asymptomatic and constitutionally well, although pruritus may be severe. The lesions may be confused with those of lichen planus and rarely coexist with them.

Differential Diagnosis

Widespread keratosis pilaris can also be confused with lichen nitidus, but the follicular localization of the papules and the absence of Koebner phenomenon in the former distinguish them. Verruca plana (flat warts) if small and uniform in size may occasionally resemble lichen nitidus.

Histology

Although the diagnosis can be made clinically, a biopsy is occasionally indicated. The lichen nitidus papule consists of sharply circumscribed nests of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the upper dermis enclosed by clawlike epidermal rete ridges.

649.9 Lichen Striatus

Clinical Manifestations

A benign, self-limited eruption, lichen striatus consists of a continuous or discontinuous linear band of papules in a Blaschkoid distribution. The primary lesion is a flat-topped, red to violaceous papule covered with fine scale. Aggregates of these papules form multiple bands or plaques. In black patients, the lesions may be hypopigmented. The eruption evolves over a period of days or weeks in an otherwise healthy child, remains stationary for weeks to months, and finally remits without sequelae usually within 2 years. Symptoms are usually absent, although some children complain of itching. Nail dystrophy may occur when the eruption involves the posterior nail fold and matrix (Fig. 649-9).

Differential Diagnosis

Lichen striatus is occasionally confused with other disorders. The initial plaque may resemble papular eczema or lichen nitidus until the linear configuration becomes apparent. Linear lichen planus and linear psoriasis are usually associated with typical individual lesions elsewhere on the body. Linear epidermal nevi are permanent lesions that often become more hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented than those of lichen striatus.

649.10 Lichen Planus

Etiology

Lichen planus is the result of an attack on the skin by cytotoxic T cells. The cause is unknown, but granzyme B and granulysin are markedly increased in skin involved with lichen planus.

Clinical Manifestations

This is a rare disorder in young children and uncommon in older ones. It is more often seen in children from the Indian subcontinent. The primary lesion is a violaceous, sharply demarcated, polygonal papule with fine lines or thin white scales on the surface. Papules may coalesce to form large plaques (Fig. 649-10). The papules are intensely pruritic, and additional papules are often induced by scratching (Koebner phenomenon) so that lines of them are often detected. Sites of predilection are the flexor surfaces of the wrists, the forearms, and the inner aspects of the thighs. Characteristic lesions of mucous membranes consist of pinhead-sized white papules that coalesce to form reticulated and lacy patterns on the oral mucosa and sometimes on the lips and tongue.

Acute eruptive lichen planus is probably the most common form in children. The lesions erupt in an explosive fashion, much like a viral exanthem, and spread to involve most of the body surface. Hypertrophic, linear, bullous, atrophic, annular, follicular, erosive, and ulcerative forms of lichen planus may also occur. Nail involvement may develop in the chronic forms but is rarely evident in children. The disorder may persist for months to years, but the acute eruptive form is most likely to involute permanently. Intense hyperpigmentation frequently persists for a long time after the resolution of lesions.

Histology

The histopathologic findings in lichen planus are specific, consisting of irregular acanthosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and basal cell degeneration with a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate at the epidermal-dermal junction. Pigment incontinence is frequently seen. Biopsy is indicated if the diagnosis is unclear.

Treatment

Treatment is directed at alleviation of the intense pruritus and amelioration of the skin lesions. Oral antihistamines are often helpful. The skin lesions respond best to regular applications of a high potency topical corticosteroid preparation. Rarely, systemic corticosteroid therapy is necessary to gain control of widespread, intractable lesions. Phototherapy has also been used for extensive disease.

649.11 Porokeratosis

Etiology

Porokeratosis is a disorder of epidermal keratinization. The etiology is unknown except for the disseminated actinic form, which is secondary to chronic sun exposure.

Clinical Manifestations

Porokeratosis is a rare, chronic, progressive disease. Several forms have been delineated: solitary plaques, linear porokeratosis, hyperkeratotic lesions of the palms and soles, disseminated eruptive lesions, and superficial actinic porokeratosis. Other types of porokeratosis are more common in males and begin in childhood. Sites of predilection are the limbs, face, neck, and genitals. The primary lesion is a small, keratotic papule that enlarges peripherally so that the center becomes depressed, with the edge forming an elevated wall or collar (Fig. 649-11). The configuration of the plaque may be round, oval, or gyrate. The elevated border is split by a thin groove from which minute cornified projections protrude. The enclosed central area is yellow, gray, or tan and sclerotic, smooth, and dry, whereas the hyperkeratotic border is a darker gray, brown, or black. The disease is slowly progressive but relatively asymptomatic. Malignant degeneration to squamous cell carcinoma has been reported in long-standing cases.

Histology

A skin biopsy discloses the characteristic cornoid lamella (plug of stratum corneum cells with retained nuclei), which is responsible for the invariable linear ridge of the lesion.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of porokeratosis includes warts, epidermal nevi, lichen planus, granuloma annulare, and elastosis perforans serpiginosa.

649.12 Papular Acrodermatitis of Childhood (Gianotti-Crosti Syndrome)

Etiology/Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, also known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood, is unclear, but an immunologic reaction to viral infections and immunizations has been postulated. In an Italian cohort, this eruption was initially associated with primary liver infection by hepatitis B virus. The disease is usually benign and, in the USA, is rarely associated with hepatitis. This eruption has been seen in children after immunizations (hepatitis A, others) and in patients infected with Epstein-Barr virus (most common association), coxsackievirus A16, parainfluenza virus, and other viral infections.

Clinical Manifestations

This distinctive eruption is occasionally associated with malaise and low-grade fever but few other constitutional symptoms. The incidence peaks in early childhood. Occurrences are usually sporadic, but epidemics have been recorded. The skin lesion is a monomorphous, usually nonpruritic, flat-topped, firm, dusky, or coppery red papule ranging in size from 1 to 10 mm (Fig. 649-12), although there is considerable variation in lesion type between patients. The papules appear in crops and may become profuse but remain discrete, forming a symmetric eruption on the face, buttocks, and limbs, including the palms and soles. The papules often have the appearance of vesicles; when opened, however, no fluid is obtained. The papules sometimes become hemorrhagic. Lines of papules (Koebner phenomenon) may be noted on the extremities. The trunk is relatively spared, as are the scalp and mucous membranes. Generalized lymphadenopathy and hepatomegaly (in patients with hepatitis B viremia) constitute the only other abnormal physical findings. The eruption resolves spontaneously in 15-60 days. Lymphadenopathy and hepatomegaly, if present, may persist for several months. Elevation of serum transaminase and alkaline phosphatase values without concomitant hyperbilirubinemia is usual.

Histology

Skin biopsy in Gianotti-Crosti syndrome is not specific, being characterized by a perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate and capillary endothelial swelling.

Differential Diagnosis

Papular acrodermatitis can be confused with lichen planus, erythema multiforme, histiocytosis X, and Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

649.13 Acanthosis Nigricans

See also Chapter 44.

Etiology

The skin lesions of acanthosis nigricans appear to be a manifestation of insulin resistance or mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor genes. The clinical severity and histopathologic features of acanthosis nigricans correlate positively with the degree of hyperinsulinism. Insulin resistance with compensatory hyperinsulinism may lead to insulin binding to and activation of insulin-like growth factor receptors, promoting epidermal growth. In the paraneoplastic form in adults, tumor-secreted growth factors and resultant hyperinsulinemia may be the proximate etiology of acanthosis nigricans. In familial cases, acanthosis nigricans is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait.

Clinical Manifestations

Acanthosis nigricans is characterized by hyperpigmented velvety, hyperkeratotic, plaques that are most often localized to the neck, axillae (Fig. 649-13), inframammary areas, groin, inner thighs, and anogenital region. Acanthosis nigricans has classically been associated with obesity; drugs such as nicotinic acid; endocrinopathies, most commonly, diabetes mellitus and hyperandrogenic or hypogonadal syndromes; and genetic disorders caused by mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor genes. Acanthosis nigricans is found more commonly in African-American and Hispanic children. It is seen in >60% of children with a body mass index >98%. Although acanthosis nigricans is associated with malignancy in adults, this is rare in childhood.

Histology

The histologic changes are those of papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis rather than acanthosis or excessive pigment formation.

Treatment

This skin disorder is extremely difficult to treat but may be improved by palliation of the underlying disorder. Acanthosis nigricans in the obese child is associated with risk factors for glucose homeostasis abnormalities, and counseling families on its causes and consequences may motivate them to make healthy lifestyle changes that can decrease the risk for development of cardiac disease and diabetes mellitus. In children with obesity-related acanthosis nigricans, weight loss should be the primary goal. In all children with acanthosis nigricans, treatment with 40% urea cream may be helpful.