Chapter 658 Cutaneous Fungal Infections

Tinea Versicolor

A common, innocuous, chronic fungal infection of the stratum corneum, tinea versicolor is caused by the dimorphic yeast Malassezia globosa. The synonyms Pityrosporum ovale and Pityrosporum orbiculare were used previously to identify the causal organism.

Etiology

M. globosa is part of the indigenous flora, predominantly in the yeast form, and is found particularly in areas of skin that are rich in sebum production. Proliferation of filamentous forms occurs in the disease state. Predisposing factors include a warm, humid environment, excessive sweating, occlusion, high plasma cortisol levels, immunosuppression, malnourishment, and genetically determined susceptibility. The disease is most prevalent in adolescents and young adults.

Clinical Manifestations

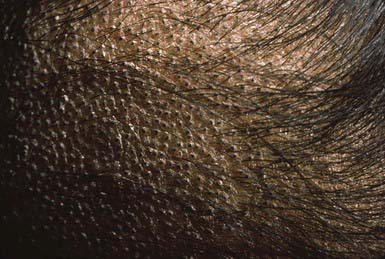

The lesions of tinea versicolor vary widely in color. In white individuals, they are typically reddish brown, whereas in black individuals they may be either hypopigmented or hyperpigmented. The characteristic macules are covered with a fine scale. They often begin in a perifollicular location, enlarge, and merge to form confluent patches, most commonly on the neck, upper chest, back, and upper arms (Fig. 658-1). Facial lesions are common in adolescents; lesions occasionally appear on the forearms, dorsum of the hands, and pubis. There may be little or no pruritus. Involved areas do not tan after sun exposure. A papulopustular perifollicular variant of the disorder may occur on the back, chest, and sometimes the extremities.

Differential Diagnosis

Examination with a Wood lamp discloses a yellowish gold fluorescence. A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation of scrapings is diagnostic, demonstrating groups of thick-walled spores and myriad short, thick, angular hyphae resembling macaroni and meatballs. Skin biopsy, including culture and special stains for fungi (periodic acid–Schiff), are often necessary to make the diagnosis in cases of primarily follicular involvement. Microscopically, organisms and keratinous debris can be seen within dilated follicular ostia.

Tinea versicolor must be distinguished from dermatophyte infections, seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis alba, and secondary syphilis. Tinea versicolor may mimic nonscaling pigmentary disorders, such as postinflammatory pigmentary change, if a patient has removed the scales by scrubbing. M. globosa folliculitis must be distinguished from the other forms of folliculitis.

Treatment

Many therapeutic agents can be used to treat this disease successfully. The causative agent, a normal human saprophyte, is not eradicated from the skin, however, and the disorder recurs in predisposed individuals. Appropriate topical therapy may include one of the following: a selenium sulfide suspension applied overnight for 1 wk followed by 1 night per wk for 4 wk; an imidazole or terbinafine cream may be used twice daily for 2-4 wk. Oral therapy may be more convenient and may be achieved successfully with ketoconazole or fluconazole, 400 mg, repeated in 1 wk, or itraconazole, 200 mg/24 hr for 5-7 days. Recurrent episodes continue to respond promptly to these agents. Maintenance therapy with selenium sulfide applied overnight once a week may be used.

Dermatophytoses

Dermatophytoses are caused by a group of closely related filamentous fungi with a propensity for invading the stratum corneum, hair, and nails. The 3 principal genera responsible for infections are Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton.

Etiology

Trichophyton spp. cause lesions of all keratinized tissue, including skin, nails, and hair. T Trichophyton rubrum is the most common dermatophyte pathogen. Microsporum spp. principally invade the hair, and the Epidermophyton spp. invade the intertriginous skin. Dermatophyte infections are designated by the word tinea followed by the Latin word for the anatomic site of involvement. The dermatophytes are also classified according to source and natural habitat. Fungi acquired from the soil are called geophilic. They infect humans sporadically, inciting an inflammatory reaction. Dermatophytes that are acquired from animals are zoophilic. Transmission may be through direct contact or indirectly by infected animal hair or clothing. Infected animals are frequently asymptomatic. Dermatophytes acquired from humans are referred to as anthropophilic. These infestations range from chronic low-grade to acute inflammatory disease. Epidermophyton infections are transmitted only by humans, but various species of Trichophyton and Microsporum can be acquired from both human and nonhuman sources.

Epidemiology

Host defense has an important influence on the severity of the infection. Disease tends to be more severe in individuals with diabetes mellitus, lymphoid malignancies, immunosuppression, and states with high plasma cortisol levels, such as Cushing syndrome. Some dermatophytes, most notably the zoophilic species, tend to elicit more severe, suppurative inflammation in humans. Some degree of resistance to re-infection is acquired by most infected persons and may be associated with a delayed hypersensitivity response. No relationship has been demonstrated, however, between antibody levels and resistance to infection. The frequency and severity of infection are also affected by the geographic locale, the genetic susceptibility of the host, and the virulence of the strain of dermatophyte. Additional local factors that predispose to infection include trauma to the skin, hydration of the skin with maceration, occlusion, and elevated temperature.

Occasionally, a secondary skin eruption, referred to as a dermatophytid or “id” reaction, appears in sensitized individuals and has been attributed to circulating fungal antigens derived from the primary infection. The eruption is characterized by grouped papules (Fig. 658-2) and vesicles and, occasionally, by sterile pustules. Symmetric urticarial lesions and a more generalized maculopapular eruption also can occur. Id reactions are most often associated with tinea pedis but also occur with tinea capitis.

Tinea Capitis

Clinical Manifestations

Tinea capitis is a dermatophyte infection of the scalp most often caused by Trichophyton tonsurans, occasionally by Microsporum canis, and, much less commonly, by other Microsporum and Trichophyton spp. It is particularly common in black children age 4-14 yr. In Microsporum and some Trichophyton infections, the spores are distributed in a sheath-like fashion around the hair shaft (ectothrix infection), whereas T. tonsurans produces an infection within the hair shaft (endothrix). Endothrix infections may continue past the anagen phase of hair growth into telogen and are more chronic than infections with ectothrix organisms that persist only during the anagen phase. T. tonsurans is an anthropophilic species acquired most often by contact with infected hairs and epithelial cells that are on such surfaces as theater seats, hats, and combs. Dermatophyte spores may also be airborne within the immediate environment, and high carriage rates have been demonstrated in noninfected schoolmates and household members. Microsporum canis is a zoophilic species that is acquired from cats and dogs.

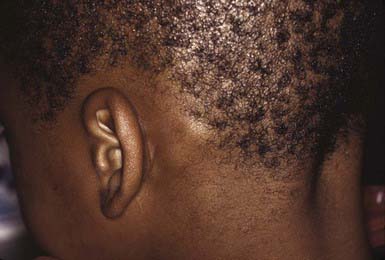

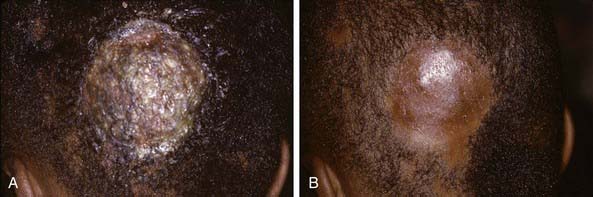

The clinical presentation of tinea capitis varies with the infecting organism. Endothrix infections such as those caused by T. tonsurans create a pattern known as “black-dot ringworm,” characterized initially by many small circular patches of alopecia in which hairs are broken off close to the hair follicle (Fig. 658-3). Another clinical variant manifests as diffuse scaling, with minimal hair loss secondary. It strongly resembles seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, or atopic dermatitis (Fig. 658-4). T. tonsurans may also produce a chronic and more diffuse alopecia. Lymphadenopathy is common (Fig. 658-5). A severe inflammatory response produces elevated, boggy granulomatous masses (kerions), which are often studded with pustules (Fig. 658-6A). Fever, pain, and regional adenopathy are common, and permanent scarring and alopecia may result (Fig. 658-6B). The zoophilic organism M. canis or the geophilic organism Microsporum gypseum also may cause kerion formation. The pattern produced by Microsporum audouinii, the most common cause of tinea capitis in the 1940s and 1950s, is characterized initially by a small papule at the base of a hair follicle. The infection spreads peripherally, forming an erythematous and scaly circular plaque (ringworm) within which the infected hairs become brittle and broken. Numerous confluent patches of alopecia develop, and patients may complain of severe pruritus. M. audouinii infection is no longer common in the USA. Favus is a chronic form of tinea capitis that is rare in the USA and is caused by the fungus Trichophyton schoenleinii. Favus starts as yellowish red papules at the opening of hair follicles. The papules expand and coalesce to form cup-shaped, yellowish, crusted patches that fluoresce dull green under a Wood lamp.

Differential Diagnosis

Tinea capitis can be confused with seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, alopecia areata, trichotillomania, and certain dystrophic hair disorders. When inflammation is pronounced, as in kerion, primary or secondary bacterial infection must also be considered. In adolescents, the patchy, moth-eaten type of alopecia associated with secondary syphilis may resemble tinea capitis. If scarring occurs, discoid lupus erythematosus and lichen planopilaris must also be considered in the differential diagnosis.

The important diagnostic procedures for the various dermatophyte diseases include examination of infected hairs with a Wood lamp, microscopic examination of KOH preparations of infected material, and identification of the etiologic agent by culture. Hairs infected with common Microsporum spp. fluoresce a bright blue-green. Most Trichophyton-infected hairs do not fluoresce.

Microscopic examination of a KOH preparation of infected hair from the active border of a lesion discloses tiny spores surrounding the hair shaft in Microsporum infections and chains of spores within the hair shaft in T. tonsurans infections. Fungal elements are not usually seen in scales. A specific etiologic diagnosis of tinea capitis may be obtained by planting broken off infected hairs on Sabouraud medium with reagents to inhibit growth of other organisms. Such identification may require 2 wk or more.

Treatment

Oral administration of griseofulvin microcrystalline (20 mg/kg/24 hr) is the recommended treatment for all forms of tinea capitis. It may be necessary for 8-12 wk and should be terminated only after fungal culture results are negative. Treatment for 1 month after a negative culture result minimizes the risk of recurrence. Adverse reactions to griseofulvin are rare but include nausea, vomiting, headache, blood dyscrasias, phototoxicity, and hepatotoxicity. Oral itraconazole is useful in instances of griseofulvin resistance, intolerance, or allergy. Itraconazole is given for 4-6 wk at a dosage of 3-5 mg/kg/24 hr with food. Capsules are preferable to the syrup, which may cause diarrhea. Terbinafine is also effective at a dosage of 3-6 mg/kg/24 hr for 4-6 wk or possibly in pulse therapy, although it has limited activity against M. canis. Neither itraconazole nor terbinafine is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of dermatophyte infections in the pediatric population. Topical therapy alone is ineffective, but it may be an important adjunct because it may decrease the shedding of spores. Asymptomatic dermatophyte carriage in family members is common. One in 3 families have at least 1 member who is a carrier. Therefore, treatment of both patient and potential carriers with a sporicidal shampoo may hasten clinical resolution. Vigorous shampooing with a 2.5% selenium sulfide, zinc pyrithione, or ketoconazole shampoo is helpful. It is not necessary to shave the scalp.

Tinea Corporis

Clinical Manifestations

Tinea corporis, defined as infection of the glabrous skin, excluding the palms, soles, and groin, can be caused by most of the dermatophyte species, although T. rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes are the most prevalent etiologic organisms. In children, infections with M. canis are also common. Tinea corporis can be acquired by direct contact with infected persons or by contact with infected scales or hairs deposited on environmental surfaces. M. canis infections are usually acquired from infected pets.

The most typical clinical lesion begins as a dry, mildly erythematous, elevated, scaly papule or plaque that spreads centrifugally and clears centrally to form the characteristic annular lesion responsible for the designation ringworm (Fig. 658-7). At times, plaques with advancing borders may spread over large areas. Grouped pustules are another variant. Most lesions clear spontaneously within several months, but some may become chronic. Central clearing does not always occur (Fig. 658-8), and differences in host response may result in wide variability in the clinical appearance—for example, granulomatous lesions called Majocchi granuloma due to penetration of organisms along the hair follicle to the level of the dermis, producing a fungal folliculitis and perifolliculitis (Fig. 658-9), and the kerion-like lesions referred to as tinea profunda. Majocchi granuloma is more common after inappropriate treatment with topical corticosteroids, especially the superpotent class.

Differential Diagnosis

Many skin lesions, both infectious and noninfectious, must be differentiated from the lesions of tinea corporis. Those most frequently confused are granuloma annulare, nummular eczema, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, erythema chronicum migrans, and tinea versicolor. Microscopic examination of KOH wet mount preparations and cultures should always be performed when fungal infection is considered. Tinea corporis usually does not fluoresce with a Wood lamp.

Treatment

Tinea corporis usually responds to treatment with one of the topical antifungal agents (e.g., imidazoles, terbinafine, naftifine) twice daily for 2-4 wk. In unusually severe or extensive disease, a course of therapy with oral griseofulvin microcrystalline may be required for 4 wk. Itraconazole has produced excellent results in many cases with a 1- to 2-wk course of oral therapy.

Tinea Cruris

Clinical Manifestations

Tinea cruris, or infection of the groin, occurs most often in adolescent males and is usually caused by the anthropophilic species Epidermophyton floccosum or Trichophyton rubrum, but occasionally by the zoophilic species T. mentagrophytes.

The initial clinical lesion is a small, raised, scaly, erythematous patch on the inner aspect of the thigh. This spreads peripherally, often developing numerous tiny vesicles at the advancing margin. It eventually forms bilateral, irregular, sharply bordered patches with hyperpigmented scaly centers. In some cases, particularly in infections with T. mentagrophytes, the inflammatory reaction is more intense and the infection may spread beyond the crural region. The penis is usually not involved in the infection, an important distinction from candidosis. Pruritus may be severe initially but abates as the inflammatory reaction subsides. Bacterial superinfection may alter the clinical appearance, and erythrasma or candidosis may coexist. Tinea cruris is more prevalent in obese persons and in persons who perspire excessively and wear tight-fitting clothing.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of tinea cruris is confirmed by culture and by demonstration of septate hyphae on a KOH preparation of epidermal scrapings. The disorder must be differentiated from intertrigo, allergic contact dermatitis, candidosis, and erythrasma. Bacterial superinfection must be precluded when there is a severe inflammatory reaction.

Tinea Pedis

Clinical Manifestations

Tinea pedis (athlete’s foot), infection of the toe webs and soles of the feet, is uncommon in young children but occurs with some frequency in preadolescent and adolescent males. The usual etiologic agents are T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and E. floccosum.

Most commonly, the lateral toe webs (3rd to 4th and 4th to 5th interdigital spaces) and the subdigital crevice are fissured, with maceration and peeling of the surrounding skin (Fig. 658-10). Severe tenderness, itching, and a persistent foul odor are characteristic. These lesions may become chronic. This type of infection may involve overgrowth by bacterial flora, including Kytococcus sedantarius, Brevibacterium epidermidis, and gram-negative organisms. Less commonly, a chronic diffuse hyperkeratosis of the sole of the foot occurs with only mild erythema (Fig. 658-11). In many cases, two feet and one hand are involved. This type of infection is more refractory to treatment and tends to recur. An inflammatory vesicular type of reaction may occur with T. mentagrophytes infection. This type is most common in young children. The lesions involve any area of the foot, including the dorsal surface, and are usually circumscribed. The initial papules progress to vesicles and bullae that may become pustular (Fig. 658-12). A number of factors, such as occlusive footwear and warm, humid weather, predispose to infection. Tinea pedis may be transmitted in shower facilities and swimming pool areas.

Differential Diagnosis

Tinea pedis must be differentiated from simple maceration and peeling of the interdigital spaces, which is common in children. Infection with Candida albicans and various bacterial organisms (erythrasma) may cause confusion or may coexist with primary tinea pedis. Contact dermatitis, vesicular foot dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and juvenile plantar dermatitis also simulate tinea pedis. Fungal mycelia can be seen on microscopic examination of a KOH preparation or by culture.

Treatment

Treatment for mild infections includes simple measures such as avoidance of occlusive footwear, careful drying between the toes after bathing, and the use of an absorbent antifungal powder such as zinc undecylenate. Topical therapy with an imidazole is curative in most cases. Each of these agents is also effective against candidal infection. Several weeks of therapy may be necessary, and low-grade, chronic infections, particularly those caused by T. rubrum, may be refractory. In refractory cases, oral griseofulvin therapy may effect a cure, but recurrences are common.

Tinea Unguium

Clinical Manifestations

Tinea unguium is a dermatophyte infection of the nail plate. It occurs most often in patients with tinea pedis, but it may occur as a primary infection. It can be caused by a number of dermatophytes, of which T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes are the most common.

The most superficial form of tinea unguium (i.e., white superficial onychomycosis) is due to T. mentagrophytes. It manifests as irregular single or numerous white patches on the surface of the nail unassociated with paronychial inflammation or deep infection. T. rubrum generally causes a more invasive, subungual infection that is initiated at the lateral distal margins of the nail and is often preceded by mild paronychia. The middle and ventral layers of the nail plate, and perhaps the nail bed, are the sites of infection. The nail initially develops a yellowish discoloration and slowly becomes thickened, brittle, and loosened from the nail bed (Fig. 658-13). In advanced infection, the nail may turn dark brown to black and may crack or break off.

Differential Diagnosis

Tinea unguium must be differentiated from various dystrophic nail disorders. Changes due to trauma, psoriasis, lichen planus, eczema, and trachyonychia can all be confused with tinea unguium. Nails infected with C. albicans have several distinguishing features, most prominently a pronounced paronychial swelling. Thin shavings taken from the infected nail, preferably from the deeper areas, should be examined microscopically with KOH and cultured. Repeated attempts may be required to demonstrate the fungus. Histologic evaluation of nail clippings with special stains for dermatophytes can be diagnostic.

The long half-life of itraconazole in the nail has led to promising trials of intermittent short courses of therapy (double the normal dose for 1 wk of each month for 3-4 mo). Oral terbinafine is also used for the treatment of onychomycosis. Terbinafine once daily for 12 weeks is more effective than itraconazole pulse therapy. Griseofulvin and application of topical fungistatic agents to the nail bed are often ineffective and are not recommended.

Tinea Nigra Palmaris

Tinea nigra palmaris is a rare but distinctive superficial fungal infection that occurs principally in children and adolescents. It is caused by the dimorphic fungus Phaeoannellomyces werneckii, which imparts a gray-black color to the affected palm. The characteristic lesion is a well-defined hyperpigmented macule. Scaling and erythema are rare, and the lesions are asymptomatic. Tinea nigra is often mistaken for a junctional nevus, melanoma, or staining of the skin by contactants. Treatment is with an imidazole antifungal.

Candidal Infections (Candidosis, Candidiasis, and Moniliasis) (Chapter 226)

The dimorphic yeasts of the genus Candida are ubiquitous in the environment, but C. albicans usually causes candidosis in children. This yeast is not part of the indigenous skin flora, but it is a frequent transient on skin and may colonize the human alimentary tract and the vagina as a saprophytic organism. Certain environmental conditions, notably elevated temperature and humidity, are associated with an increased frequency of isolation of C. albicans from the skin. Many bacterial species inhibit the growth of C. albicans, and alteration of normal flora by the use of antibiotics may promote overgrowth of the yeast.

Vaginal Candidosis (Chapters 114 and 226)

C. albicans is an inhabitant of the vagina in 5-10% of women, and vaginal candidosis is not uncommon in adolescent girls. A number of factors can predispose to this infection, including antibiotic therapy, corticosteroid therapy, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, and the use of oral contraceptives. The infection manifests as cheesy white plaques on an erythematous vaginal mucosa and a thick white-yellow discharge. The disease may be relatively mild or may produce pronounced inflammation and scaling of the external genitals and surrounding skin with progression to vesiculation and ulceration. Patients often complain of severe itching and burning in the vaginal area. Before treatment is initiated, the diagnosis should be confirmed by microscopic examination and/or culture. The infection may be eradicated by insertion of nystatin or imidazole vaginal tablets, suppositories, creams, or foam. If these products are ineffective, the addition of fluconazole 150 mg × 1 is effective.

Candidal Diaper Dermatitis

Candidal diaper dermatitis is a ubiquitous problem in infants and, although relatively benign, is often frustrating because of its tendency to recur. Predisposed infants usually carry C. albicans in their intestinal tracts, and the warm, moist, occluded skin of the diaper area provides an optimal environment for its growth. A seborrheic, atopic, or primary irritant contact dermatitis usually provides a portal of entry for the yeast.

The primary clinical manifestation consists of an intensely erythematous, confluent plaque with a scalloped border and a sharply demarcated edge. It is formed by the confluence of numerous papules and vesicular pustules. Satellite pustules, those that stud the contiguous skin, are a hallmark of localized candidal infections. The perianal skin, inguinal folds, perineum, and lower abdomen are usually involved (Fig. 658-14). In males, the entire scrotum and penis may be involved, with an erosive balanitis of the perimeatal skin. In females, the lesions may be found on the vaginal mucosa and labia. In some infants, the process is generalized, with erythematous lesions distant from the diaper area. In some cases, the generalized process may represent a fungal id (hypersensitivity) reaction.

The differential diagnosis of candidal diaper dermatitis includes other eruptions of the diaper area that may coexist with candidal infection. For this reason, it is important to establish a diagnosis by means of KOH preparation or culture.

Treatment consists of applications of an imidazole cream 2 times daily. The combination of a corticosteroid and an antifungal agent may be justified if inflammation is severe but may confuse the situation if the diagnosis is not firmly established. Corticosteroid should not be continued for more than a few days. Protection of the diaper area by an application of thick zinc oxide paste overlying the anticandidal preparation may be helpful. The paste is more easily removed with mineral oil than with soap and water. Fungal id reactions gradually abate with successful treatment of the diaper dermatitis or may be treated with a mild corticosteroid preparation. When recurrences of diaper candidosis are frequent, it may be helpful to prescribe a course of oral anticandidal therapy to decrease the yeast population in the gastrointestinal tract. Some infants seem to be receptive hosts for C. albicans and may reacquire the organism from a colonized adult.

Intertriginous Candidosis

Intertriginous candidosis occurs most often in the axillae and groin, on the neck (Fig. 658-15), under the breasts, under pendulous abdominal fat folds, in the umbilicus, and in the gluteal cleft. Typical lesions are large, confluent areas of moist, denuded, erythematous skin with an irregular, macerated, scaly border. Satellite lesions are characteristic and consist of small vesicles or pustules on an erythematous base. With time, intertriginous candidal lesions may become lichenified, dry, scaly plaques. The lesions develop on skin subjected to irritation and maceration. Candidal superinfection is more likely to occur under conditions that lead to excessive perspiration, especially in obese children and in children with underlying disorders, such as diabetes mellitus. A similar condition, interdigital candidosis, commonly occurs in individuals whose hands are constantly immersed in water. Fissures occur between the fingers and have red denuded centers, with an overhanging white epithelial fringe. Similar lesions between the toes may be secondary to occlusive footwear. Treatment is the same as for other candidal infections.

Perianal Candidosis

Perianal dermatitis develops at sites of skin irritation as a result of occlusion, constant moisture, poor hygiene, anal fissures, and pruritus due to pinworm infestation. It may become superinfected with C. albicans, especially in children who are receiving oral antibiotic or corticosteroid medication. The involved skin becomes erythematous, macerated, and excoriated, and the lesions are identical to those of candidal intertrigo or candidal diaper rash. Application of a topical antifungal agent in conjunction with improved hygiene is usually effective. Underlying disorders such as pinworm infection must also be treated (Chapter 285).

Candidal Granuloma

Candidal granuloma is a rare response to an invasive candidal infection of skin. The lesions appear as crusted, verrucous plaques and hornlike projections on the scalp, face, and distal limbs. Affected patients may have single or numerous defects in immune mechanisms, and the granulomas are often refractory to topical therapy. A systemic anticandidal agent may be required for palliation or eradication of the infection.

Andrews MD, Burns M. Common tinea infections in children. Am Fam Physician. 2008;15:1415-1420.

Elewski BE, Caceres HW, DeLeon L, et al. Terbinafine hydrochloride oral granules versus oral griseofulvin suspension in children with tinea capitis: results of two randomized, investigator-blinded, multicenter, international, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:41-54.

Panackal AA, Halpern EF, Watson AJ. Cutaneous fungal infections in the United States: analysis of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS), 1995–2004. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:704-712.