Chapter 661 Acne

Acne Vulgaris

Acne, particularly the comedonal form, occurs in 80% of adolescents.

Pathogenesis

Lesions of acne vulgaris develop in sebaceous follicles, which consist of large, multilobular sebaceous glands that drain their products into the follicular canals. The initial lesion of acne is a microcomedone, which progresses to a comedone. A comedone is a dilated epithelium-lined follicular sac filled with lamellated keratinous material, lipid, and bacteria. An open comedone, known as a blackhead, has a patulous pilosebaceous orifice that permits visualization of the plug. An open comedone becomes inflammatory less commonly than does a closed comedone or whitehead, which has only a pinpoint opening. An inflammatory papule or nodule develops from a comedone that has ruptured and extruded its follicular contents into the subadjacent dermis, inducing a neutrophilic inflammatory response. If the inflammatory reaction is close to the surface, a papule or pustule develops. If the inflammatory infiltrate develops deeper in the dermis, a nodule forms. Suppuration and an occasional giant cell reaction to the keratin and hair are the cause of nodulocystic lesions. These are not true cysts but liquefied masses of inflammatory debris.

The primary pathogenetic alterations in acne are (1) abnormal keratinization of the follicular epithelium, resulting in impaction of keratinized cells within the follicular lumen; (2) increased sebaceous gland production of sebum; (3) proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes within the follicle; and (4) inflammation. Comedonal acne (Fig. 661-1), particularly of the central face, is frequently the first sign of pubertal maturation. At puberty, the sebaceus gland enlarges and sebum production increases in response to the increased activities of androgens of primarily adrenal origin. Most patients with acne do not have endocrine abnormalities. Hyperresponsiveness of the sebocyte to androgens is likely involved in determining the severity of acne in a given individual. Sebocytes and follicular keratinocytes contain 5α-reductase and 3β- and 17β-hydroxyl-steroid dehydrogenase, which are capable of metabolizing androgens. A significant number of women with acne (25-50%), particularly those with relatively mild papulopustular acne, note that their acne flares about 1 wk before menstruation.

Freshly formed sebum consists of a mixture of triglycerides, wax esters, squalene, and sterol esters. Normal follicular bacteria produce lipases that hydrolyze sebum triglycerides to free fatty acids. Those of medium-chain length (C8-C14) may be provocative factors in initiating an inflammatory reaction. Sebum also provides a favorable substrate for proliferation of bacteria. P. acnes appears to be largely responsible for the formation of free fatty acids. Skin surface P. acnes counts do not correlate with the severity of acne. There is a correlation between reduction of P. acnes count and improvement in acne vulgaris. It is probable that bacterial proteases, hyaluronidases, and hydrolytic enzymes produce biologically active extracellular materials that increase the permeability of the follicular epithelium. Chemotactic factors released by the intrafollicular bacteria attract neutrophils and monocytes. Lysosomal enzymes from the neutrophils, released in the process of phagocytizing the bacteria, further disrupt the integrity of the follicular wall and intensify the inflammatory reaction.

Clinical Manifestations

Acne vulgaris is characterized by 4 basic types of lesions: open and closed comedones, papules, pustules (Fig. 661-2), and nodulocystic lesions (Fig. 661-3 and Table 661-1). One or more types of lesions may predominate. In its mildest form, which is often seen early in adolescence, lesions are limited to comedones on the central area of the face. Lesions may also involve the chest, upper back, and deltoid areas. A predominance of lesions on the forehead, particularly closed comedones, is often attributable to prolonged use of greasy hair preparations (pomade acne) (Fig. 661-4). Marked involvement on the trunk is most often seen in males. Lesions often heal with temporary postinflammatory erythema and hyperpigmentation. Pitted, atrophic, or hypertrophic scars may be interspersed, depending on the severity, depth, and chronicity of the process. Diagnosis of acne is rarely difficult, although flat warts, folliculitis, and other types of acne may be confused with acne vulgaris.

Table 661-1 CLASSIFICATION OF ACNE

| SEVERITY | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Mild | Comedones (noninflammatory lesions) are the main lesions. Papules and pustules may be present but are small and few in number (generally < 10). |

| Moderate | Moderate numbers of papules and pustules (10-40) and comedones (10-40) are present. Mild disease of the trunk may also be present. |

| Moderately severe | Numerous papules and pustules are present (40-100), usually with many comedones (40-100) and occasional larger, deeper nodular inflamed lesions (up to 5). Widespread affected areas usually involve the face, chest, and back. |

| Severe | Nodulocystic acne and acne conglobata with many large, painful nodular or pustular lesions are present, along with many smaller papules, pustules, and comedones. |

From James WD: Clinical practice: acne, N Engl J Med 352:1463–1472, 2005.

Treatment

No evidence shows that early treatment, with the exception of isotretinoin, alters the course of acne. Acne can be controlled and severe scarring prevented by judicious maintenance therapy that is continued until the disease process has abated spontaneously. Therapy must be individualized and aimed at preventing microcomedone formation through reduction of follicular hyperkeratosis, sebum production, the P. acnes population in follicular orifices, and free fatty acid production. Initial control takes at least 6-8 wk, depending on the severity of the acne (Table 661-2 and Fig 661-5). It is also important to address the potentially severe emotional impact of acne on adolescents.

Table 661-2 TYPICAL TREATMENT REGIMENS FOR ACNE

COMEDONAL ACNE

MILD PAPULOPUSTULAR ACNE

SEVERE PAPULOPUSTULAR OR NODULAR ACNE

Figure 661-5 Acne treatment algorithm, BPO, benzoyl peroxide.

(From Thiboutot D, Gollnick H; Global Alliance to Improve Acne, et al: New insights into the management of acne: an update from the global alliance to improve outcomes in acne, J Am Acad Dermatol 60:S1–S50, 2009.)

The pediatrician must be aware of the frequently poor correlation between acne severity and psychosocial impact, particularly in adolescents. As adolescents become preoccupied with their appearance, offering treatment even to the youngster whose acne is mild may enhance self-image.

Diet

Little evidence shows that ingestion of particular foods can trigger acne flares. When a patient is convinced that certain dietary items exacerbate acne, it is prudent for him or her to omit those foods.

Climate

Climate appears to influence acne, in that improvement frequently occurs in summer and flares are more common in winter. Remission in summer may relate, in part, to the relative absence of stress. Emotional tension and fatigue seem to exacerbate acne in many individuals; the mechanism is unclear but has been proposed to relate to an increased adrenocortical response.

Cleansing

Cleansing with soap and water removes surface lipid and renders the skin less oily in appearance, but no evidence shows that surface lipid has a role in generating acne lesions. Only superficial drying and peeling are achieved by cleansing, and almost any mild soap or astringent is adequate. Repetitive cleansing can be harmful because it irritates and chaps the skin. Cleansing agents that contain abrasives and keratolytic agents, such as sulfur, resorcinol, and salicylic acid, may temporarily remove sebum from the skin surface. They exert a mild drying and peeling effect and suppress lesions to a limited degree. They do not prevent microcomedones from forming. No evidence shows that preparations containing alcohol or hexachlorophene decrease acne because surface bacteria are not involved in the pathogenesis. Greasy cosmetic and hair preparations must be discontinued because they exacerbate pre-existing acne and cause further plugging of follicular pores. Manipulation and squeezing of facial lesions only ruptures intact lesions and provokes a localized inflammatory reaction.

Topical Therapy

All topical preparations must be used for 6-8 wk before their effectiveness can be assessed. Retinoids may be used alone for mild acne, but combination therapy is frequently more effective. A popular and effective combination is use of benzoyl peroxide gel in the morning and a retinoid at night.

Retinoids

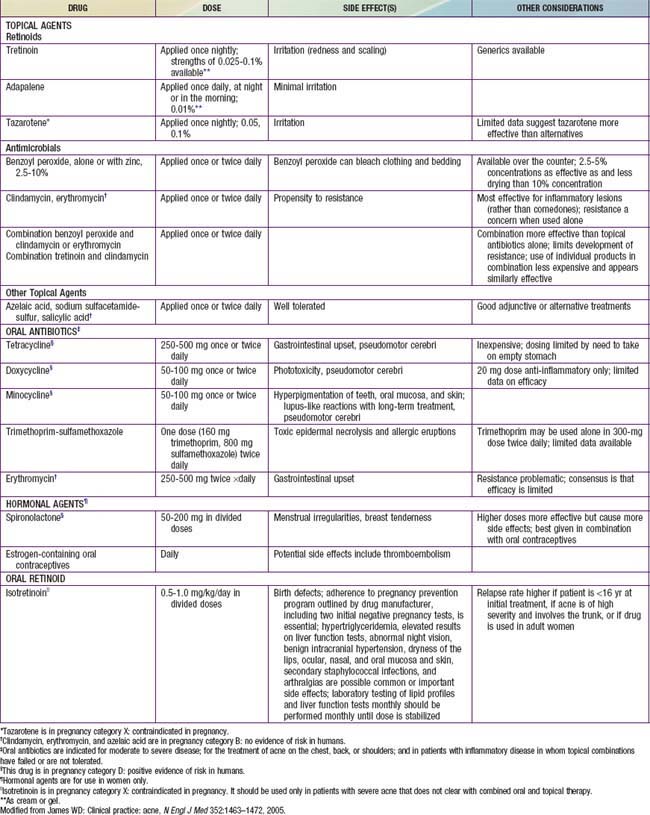

A topical retinoid should be the primary treatment for acne vulgaris. Topical retinoids have multiple actions, including inhibition of the formation and number of microcomedones, reduction of mature comedones, reduction of inflammatory lesions, and production of normal desquamation of the follicular epithelium. Retinoids should be applied daily to all the affected areas. The main side effects of retinoids are irritation and dryness. Not all patients initially tolerate daily use of a retinoid. It is prudent to begin therapy every other or every third day and slowly increase the frequency of application as tolerated. Tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene (Table 661-3) are the available retinoids. They are all approximately equal in efficacy, although adapalene is less irritating and tazarotene works slightly better for comedonal acne.

Benzoyl Peroxide

Benzoyl peroxide is primarily an antimicrobial agent. It has an advantage over topical antibiotics in that it does not enhance antimicrobial resistance. It is available in multiple formulations and concentrations. The gel formulations are preferred, owing to better stability and more consistent release of the active ingredient. Washes and cleansers are useful for covering large surface areas such as the chest and back. As with retinoids, the main side effects are irritation and drying. Benzoyl peroxide can also bleach clothing.

Topical Antibiotics

Topical antibiotics are indicated for the treatment of inflammatory acne. Clindamycin is the most commonly used. It is not as effective as oral antibiotics. It should not be used as monotherapy because it does not inhibit microcomedone formation and it has the potential to induce antimicrobial resistance. Irritation and dryness are generally less than with retinoids or benzoyl peroxide. Topical antibiotics are best used as combination products. The most common is benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin. A combination tretinoin/clindamycin product may also be used.

Systemic Therapy

Antibiotics, especially tetracycline and its derivatives (see Table 661-3), are indicated for treatment of patients whose acne has not responded to topical medications, who have moderate to severe inflammatory papulopustular and nodulocystic acne, and who have a propensity for scarring. Tetracycline and its derivatives act by reducing the growth and metabolism of P. acnes. They also have anti-inflammatory properties. For most adolescent patients, therapy may be initiated twice daily, for at least 6-8 wk, followed by a gradual decrease to the minimal effective dose. The drugs should always be administered in combination with a topical retinoid and topical benzoyl peroxide, but not topical antibiotics. Tetracycline absorption is inhibited by food, milk, iron supplements, aluminum hydroxide gel, and calcium-magnesium salts. It should be taken on an empty stomach 1 hr before or 2 hr after meals. Minocycline and doxycycline may be taken with food. Side effects of tetracycline and derivatives are rare. Side effects of tetracycline include vaginal candidosis, particularly in those who take tetracycline concurrently with oral contraceptives; gastrointestinal irritation; phototoxic reactions, including onycholysis and brown discoloration of nails; esophageal ulceration; inhibition of fetal skeletal growth; and staining of growing teeth, precluding its use during pregnancy and in those <8 yr. Doxycycline is the most photosensitizing of the tetracycline derivatives. Rarely, minocycline causes dizziness, intracranial hypertension, bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes, hepatitis, and a lupus-like syndrome. A possible complication of prolonged systemic antibiotic use is proliferation of gram-negative organisms, particularly Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, producing severe, refractory folliculitis.

Women who have acne and hormonal abnormalities, whose acne is unresponsive to antibiotic therapy, or who are not candidates for isotretinoin therapy should be considered for a trial of hormonal therapy. Oral contraceptive pills are the primary form of hormonal therapy. Spironolactone has also shown effectiveness.

Isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid; Accutane) is indicated for severe nodulocystic acne and moderate to severe acne that has not responded to conventional therapy. The recommended dosage is 0.5-1.0 mg/kg/24 hr. A standard course in the USA lasts 16-20 wk. At the end of one course of isotretinoin, 40% of patients are cured, 45% need conventional topical and/or oral medications to maintain adequate control, and 15% have relapses and need an additional course of isotretinoin. Dosages <0.5 mg/kg/24 hr, or a cumulative dose of <120 mg/kg, are associated with a significantly higher rate of treatment failure and relapse. If the disease process is not in remission 2 mo after the first course of isotretinoin, a second course should be considered. Isotretinoin reduces size and secretion of sebaceous glands, normalizes follicular keratinization, prevents new microcomedone formation, decreases the population of P. acnes, and exerts an anti-inflammatory effect.

Isotretinoin use has many side effects. It is highly teratogenic and is absolutely contraindicated in pregnancy. Pregnancy should be avoided for 6 wk after discontinuation of therapy. Two forms of birth control are required, as are monthly pregnancy tests. Concerns over cases of pregnancy despite warnings have prompted a manufacturer registration program, iPLEDGE (www.ipledgeprogram.com), which requires physician enrollment and careful patient pregnancy screening in order to prescribe isotretinoin. Many patients also experience cheilitis, xerosis, periodic epistaxis, and blepharoconjunctivitis. Increased serum triglyceride and cholesterol levels are also common. It is important to rule out pre-existing liver disease and hyperlipidemia before initiating therapy and to recheck laboratory values 4 wk after commencement of therapy. Less common but significant side effects include arthralgias, myalgias, temporary thinning of the hair, paronychia, increased susceptibility to sunburn, formation of pyogenic granulomas, and colonization of the skin with Staphylococcus aureus, leading to impetigo, secondarily infected dermatitis, and scalp folliculitis. Rarely, hyperostotic lesions of the spine develop after more than 1 course of isotretinoin. Concomitant use of tetracycline and isotretinoin is contraindicated because either drug, but particularly when they are used together, can cause benign intracranial hypertension. Although no cause-and-effect relationship has been established, drug-induced mood changes and depression and/or suicide have mandated close attention to psychiatric well-being before and during isotretinoin prescription.

Surgical Therapy

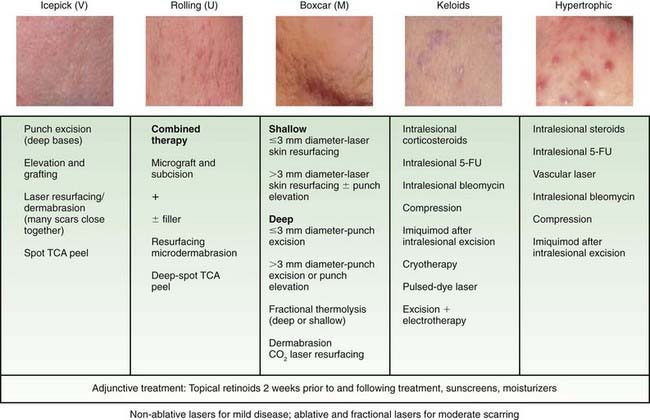

Intralesional injection of low-dose (3-5 mg/mL) mid-potency glucocorticoids (e.g., triamcinolone) with a 30-gauge needle on a tuberculin syringe may hasten the healing of individual, painful nodulocystic lesions. Dermabrasion or laser peel to minimize scarring should be considered only after the active process is quiescent. The management of scarring is described in Figure 661-6.

Figure 661-6 Treatment options for acne scars. CO2, carbon dioxide; FU, fluorouracil; TCA, trichloroacetic acid.

(From Thiboutot D, Gollnick H; Global Alliance to Improve Acne, et al: New insights into the management of acne: an update from the global alliance to improve outcomes in acne, J Am Acad Dermatol 60:S1–S50, 2009.)

The role of pulsed dye laser in the treatment of inflammatory acne is controversial and inconclusive.

Drug-Induced Acne

Pubertal and postpubertal patients who are receiving systemic corticosteroid therapy are predisposed to steroid-induced acne. This monomorphous folliculitis occurs primarily on the face, neck, chest (Fig. 661-7), shoulders, upper back, arms, and rarely on the scalp. Onset follows the initiation of steroid therapy by about 2 wk. The lesions are small, erythematous papules or pustules that may erupt in profusion and are all in the same stage of development. Comedones may occur subsequently, but nodulocystic lesions and scarring are rare. Pruritus is occasional. Although steroid acne is relatively refractory if the medication is continued, the eruption may respond to use of tretinoin and a benzoyl peroxide gel.

Other drugs that can induce acneiform lesions in susceptible individuals include isoniazid, phenytoin, phenobarbital, trimethadione, lithium carbonate, androgens (anabolic steroids), and vitamin B12.

Halogen Acne

Administration of medications containing iodides or bromides or, rarely, ingestion of massive amounts of vitamin-mineral preparations or iodine-containing “health foods” such as kelp may induce halogen acne. The lesions are often very inflammatory. Discontinuation of the provocative agent and appropriate topical preparations usually achieve reasonable therapeutic results.

Chloracne

Chloracne is due to external contact with, inhalation of, or ingestion of halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons, including polyhalogenated biphenyls, polyhalogenated naphthalenes, and dioxins. Lesions are primarily comedonal. Inflammatory lesions are infrequent but may include papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts. Healing occurs with atrophic or hypertrophic scarring. The face, postauricular regions, neck, axillae, genitals, and chest are most commonly involved. The nose is often spared. In cases of severe exposure, associated findings may include hepatitis, production of porphyrins, bulla formation on sun-exposed skin, hyperpigmentation, hypertrichosis, and palmar and plantar hyperhidrosis. Topical or oral retinoids may be effective; benzoyl peroxide and antibiotics are generally ineffective.

Neonatal Acne

Approximately 20% of normal neonates demonstrate at least a few comedones in the first mo of life. Closed comedones predominate on the cheeks and forehead (Fig. 661-8); open comedones and papulopustules occur occasionally. The cause of neonatal acne is unknown but has been attributed to placental transfer of maternal androgens, hyperactive neonatal adrenal glands, and a hypersensitive neonatal end-organ response to androgenic hormones. The hypertrophic sebaceous glands involute spontaneously over a few months, as does the acne. Treatment is usually unnecessary. If desired, the lesions can be treated effectively with topical tretinoin and/or benzoyl peroxide.

Infantile Acne

Infantile acne usually manifests after 1 yr of life, more commonly in boys than girls. Acne lesions are more numerous, pleomorphic, severe, and persistent than in neonatal acne (Fig. 661-9). Open and closed comedones predominate on the face. Papules and pustules occur frequently, but only occasionally do nodulocystic lesions develop. Pitted scarring is seen in 10-15%. The course may be relatively brief, or the lesions may persist for many months, although the eruption generally resolves by age 3 yr. Use of topical benzoyl peroxide gel and tretinoin usually clears the eruption within a few weeks. Oral erythromycin is occasionally necessary. A child with refractory acne warrants a search for an abnormal source of androgens, such as a virilizing tumor or congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Tropical Acne

A severe form of acne occurs in tropical climates and is believed to be due to the intense heat and humidity. Hydration of the pilosebaceous duct pore may accentuate blockage of the duct. Affected individuals tend to have an antecedent history of adolescent acne that is quiescent at the time of the eruption. Lesions occur mainly on the entire back, chest, buttocks, and thighs, with a predominance of suppurating papules and nodules. Secondary infection with S. aureus may be a complication. The eruption is refractory to acne therapy if the environmental factors are not eliminated.

Acne Conglobata

Acne conglobata is a chronic progressive inflammatory disease that occurs mainly in men, and more commonly in white than in black individuals, but it may begin during adolescence. Patients usually have a history of pre-existing acne vulgaris. The principal lesion is the nodule, although there is often a mixture of comedones with multiple pores, papules, pustules, nodules, cysts, abscesses, and subcutaneous dissection with formation of multichanneled sinus tracts. Severe scarring is characteristic. The face is relatively spared, but in addition to the back and chest, the buttocks, abdomen, arms, and thighs may be involved. Constitutional symptoms and anemia may accompany the inflammatory process. Coagulase-positive staphylococci and β-hemolytic streptococci are frequently cultured from lesions but do not appear to be primarily involved in the pathogenesis. Acne conglobata occasionally occurs in association with hidradenitis suppurativa and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp (as the follicular occlusion triad) and may be complicated by erosive arthritis and ankylosing spondyloarthritis. Endocrinologic studies are not revealing. Routine acne therapy is generally ineffective. Systemic therapy with a corticosteroid may be required to suppress the intense inflammatory activity. Isotretinoin is the most effective form of therapy for some patients but may produce a flare after its initiation.

Acne Fulminans (Acute Febrile Ulcerative Acne)

Acne fulminans is characterized by abrupt onset of extensive inflammatory, tender ulcerative acneiform lesions on the back and chest of male teenagers. The distinctive feature is the tendency for large nodules to form exudative, necrotic, ulcerated, crusted plaques. Lesions often spare the face and heal with scarring. A preceding history of mild papulopustular or nodular acne is noted in most patients. Constitutional symptoms and signs are common, including fever, debilitation, arthralgias, myalgias, weight loss, and leukocytosis. Blood cultures are sterile. Lesions of erythema nodosum sometimes develop on the shins. Osteolytic bone lesions may develop in the clavicle, sternum, and epiphyseal growth plates; affected bones appear normal or have slight sclerosis or thickening on healing. Salicylates may be helpful for the myalgias, arthralgias, and fever. Corticosteroids (1.0 mg/kg of prednisone) are started first. Then 1 wk later, isotretinoin (0.5-1 mg/kg) is added. Dapsone may be effective if isotretinoin cannot be used. The corticosteroid dosage is tapered over approximately 6 wk. Antibiotics are not indicated unless there is evidence of secondary infection. Compared with acne conglobata, acne fulminans occurs in younger patients, is more explosive in onset, more commonly has associated constitutional symptoms and ulcerated crusted lesions, and less commonly has multiheaded comedones or involves the face.

Krakowski AC, Stendardo S, Eichenfield LF. Practical considerations in acne treatment and the clinical impact of topical combination therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:S1-S14.

Magin P, Sullivan J. Suicide attempts in people taking isotretinoin for acne. BMJ. 2010;341:c5866.

The Medical Letter. Adapalene-benzoyl peroxide (Epiduo) for acne. Med Lett. 2009;51:31-32.

2010 The Medical Letter. Clindamycin-tretinoin (veltin gel) for acne. Med Lett. 2010;52:102-103.

Purdy S, de Berker D. Acne. BMJ. 2006;333:949-953.

Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the global alliance to improve outcomes in acne. Global Alliance to Improve Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:S1-S50.

Zaenglein AL, Thiboutot DM. Expert committee recommendations for acne management. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1188-1199.