Chapter 683 Performance-Enhancing Aids

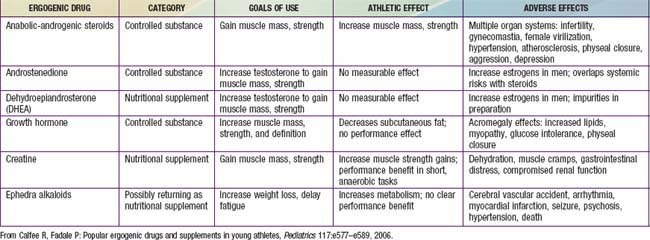

Performance-enhancing drugs have been used by athletes since at least since 776 BCE. Ergogenic aids are substances used for performance enhancement, most of which are unregulated supplements (Table 683-1). The 1994 Dietary Supplement and Health Education Act limited the ability of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to regulate any product labeled as a supplement. Many agents have significant side effects without proven ergogenic properties. In 2005, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a policy statement strongly condemning their use in children and adolescents. The US 2004 Controlled Substance Act outlawed the purchase of steroidal supplements such as tetrahydrogestrione (THG), and androstenedione (Andro), with the exception of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA).

The prevalence of lifetime steroid use is highest among boys and in the USA (5.1%); The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs found that 1% of European youth reported any use of steroids. Trends indicate that use of steroids declined by half from 2006-2010. Steroids in oral, injectable, and skin cream form are taken in various patterns. Cycling describes taking multiple doses of steroids for a period, ceasing, and then starting again. Stacking refers to the use of different types of steroids in both oral and injectable forms. Pyramiding involves slowly increasing the steroid dose to a peak amount and then gradually tapering down.

Anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) have been used in supraphysiologic doses for their ability to increase muscle size and strength and decrease body fat. The evidence of increased muscle mass and strength is controversial but is supported by objective data. The effects appear to be related to the myotrophic action at androgen receptors as well as competitive antagonism at catabolism-mediating corticosteroid receptors. They have significant endocrinologic side effects, such as decreased sperm count and testicular atrophy in men and menstrual irregularities and virilization in women. Hepatic problems include elevated aminotransaminases and γ-glutamyl transferase, cholestatic jaundice, peliosis hepatitis, and a variety of tumors, including hepatocellular carcinoma. There is evidence that AAS might cause cardiovascular problems as well, including higher blood pressure, lower high-density lipoprotein, higher low-density lipoprotein, higher homocysteine, and decreased glucose tolerance. The psychologic effects include aggression, several personality disorders, and a variety of other psychologic problems (anxiety, paranoia, mania, depression, psychosis). Physical findings include gynecomastia, testicular shrinkage, jaundice, acne, and marked striae. Women can develop hirsutism, voice deepening, and male-pattern baldness.

Testosterone precursors (also known as prohormones) include androstenedione and DHEA. Their use in the adolescent population has increased markedly in conjunction with reports of high-profile athletes’ use. They are androgenic but have not been proved to be anabolic. If they are anabolic at all, they work by increasing the production of testosterone. They also increase production of estrogenic metabolites. The side effects are similar to those of AAS and far outweigh any ergogenic benefit. Since January 2005, these substances cannot be sold without prescription.

Creatine is an amino acid mostly stored in skeletal muscle. Its key feature is ability to rephosphorylate adenosine diphosphate to adenosine triphosphate, therefore increasing muscle performance. Its use has increased, especially since other supplements have been withdrawn from the market. Thirty percent of high school football players have used creatine. There is evidence that creatine, as a source of increased energy, enhances strength and maximal exercise performance when used during training. There is no evidence that creatine affects hydration or temperature regulation. Concerns about nephritis in case reports have not been supported by controlled studies. However, there are few long-term studies evaluating creatine use.

American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement: use of performance enhancing substances. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1103-1106.

Calfee R, Fadale P. Popular ergogenic drugs and supplements in young athletes. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e577-e589.

The Medical Letter. Performance-enhancing drugs. Med Lett. 2004;46:57-60.

Meinhardt U, Nelson AE, Hansen JL, et al. The effects of growth hormone on body composition and physical performance in recreational athletes. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:568-577.

Miah A. Doping and the child: an ethical policy for the vulnerable. Lancet. 2005;366:874-876.

Seifert SM, Schaechter JL, Hershorin ER, et al. Health effects of energy drinks on children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):511-528.

Sjoqvist F, Garle M, Rane A. Use of doping agents, particularly anabolic steroids in sports and society. Lancet. 2008;371:1872-1882.

Tokish JM, Kocher MS, Hawkins RJ. Ergogenic aids: a review of basic science, performance, side effects, and status in sports. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1543-1553.