80

Management of Skin Grafts and Flaps

The Surgeon’s Perspective

Adam B. Strohl, and L. Scott Levin

• Advances in wound care, flap design, and microsurgical techniques that include an ever expanding armamentarium of free tissue transfer, postoperative management, and rehabilitation protocols have allowed for the continued improvement in reconstructive surgery of the upper limb.

• Soft tissue reconstruction options include primary closure, delayed primary closure, healing by secondary intention, skin grafting, local tissue transfer, free tissue transfer, and any combination of these techniques. Free tissue transfer, by definition, includes vascularized tissue such as skin, muscle, bone, fascia, or a combination of thereof that is dependent on a vascular pedicle for survival after transfer.

• An algorithmic approach to reconstruction of the upper extremity treatment of upper is based on the extent and severity of the bone and soft tissue injury or defect, the functional needs of the patient, medical comorbidities, and the availability of required tissues.

Introduction

Reconstructive surgery of the upper extremity has developed significantly over the past 6 decades after introduction of the operating microscope by Jacobsen in 1960. Microsurgical techniques as well as the continuous development of new tissue transfers have greatly enhanced the armamentarium of reconstructive surgeons.

1

The continuing evolution of wound management has facilitated a more optimal environment that promotes wound healing, rehabilitation, and recovery. Reconstructive surgery has evolved from the practice of simply providing soft tissue coverage for traumatic defects to a complex algorithmic process of wound management and optimization of function. This pathway involves thorough clinical assessment, evaluation of individual functional and social needs of the patient, creation and implementation of a surgical plan, and structured postoperative management using appropriate rehabilitation protocols. The algorithmic approach offers a reconstructive ladder for the evaluation and treatment of wounds, ranging from acute traumatic injuries to various chronic conditions, including osteomyelitis, nonhealing wounds, and defects resulting from tumor resection.

2,3

This reconstructive ladder directs the surgeon to the indicated reconstructive surgical approach based on the extent and severity of the wound, the functional needs of the patient, and the availability of required tissue elements. The initial goal of the reconstructive surgeon is the reconstitution of the soft tissue envelope, providing a well-vascularized, healthy environment to facilitate localized healing.

3

After this has been achieved, therapists can maximize outcomes, prevent secondary complications, and restore the patient’s function. With successful recovery and healing, the reconstructive surgeon can attain the ultimate goal of optimizing rehabilitation based on individual needs, thus maximizing functional restoration and providing patients with the opportunity for rapid social reintegration and the overall improvement of their quality of life. This chapter discusses an algorithmic approach to reconstruction of the hand and upper extremity, providing examples of reconstructive options for surgical problems, ranging from skin grafts, to local tissue flaps, to advanced free tissue transfer.

Patient Assessment

The first step in developing a reconstructive strategy is the assessment of the patient. The surgeon must recognize the clinical reconstructive needs of the patient based on the severity of a traumatic injury, the extent and complexity of a chronic wound, or a malignant tumor requiring resection. Important considerations include age, significant medical morbidities, preinjury functional status, occupation, dominance of the extremity involved, psychosocial considerations, and individual patient motivation and compliance. In patients with acute traumatic injuries of the upper extremity, a thorough clinical evaluation is necessary to first rule out the presence of other significant life-threatening conditions or injuries that will alter rehabilitation capacity.

4

For chronic wounds, it is essential to identify and address causative factors such as malnutrition and vascular insufficiency. With wounds secondary to malignancy, the determination must be made whether additional resections will be needed as well as the need for chemotherapy or radiation therapy, which have deleterious effects on wound healing. In the cases of traumatic injury when a patient is hemodynamically stable, an assessment of the extremities can occur. Evaluation of the hand and upper extremity involves a systematic approach to the extremity as a functional organ.

1,4

Complete examination includes gross visual inspection, evaluation of limb perfusion, assessment of passive and active motion, and a review of neurologic function. Imaging studies, such as radiography, ultrasonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance

imaging, or angiography, are incorporated as indicated to further establish the extent of soft tissue, bone, and vascular involvement. After the clinical needs of the patient and deficits from the wound have been clearly established, a surgical management strategy can be created to optimize the reconstruction, postoperative management, and the functional rehabilitative goals of the patient.

Management Strategy

The first step in surgical wound management is exploration, irrigation, and meticulous debridement.

4

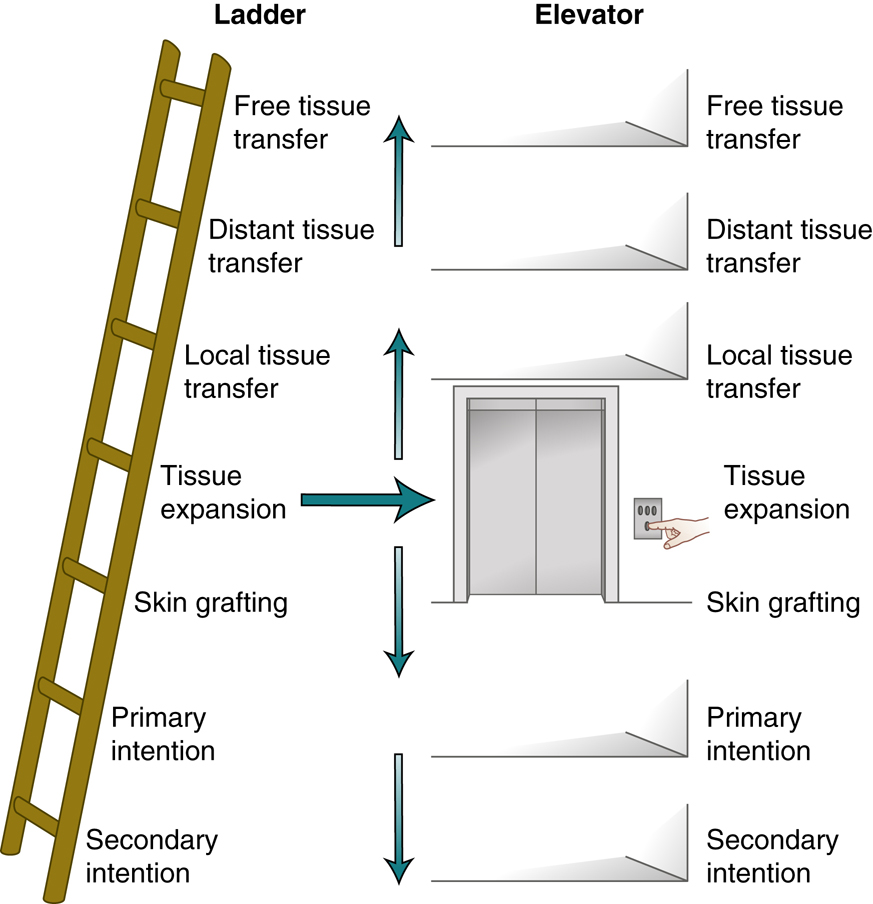

Adequate debridement of all nonviable tissues is required to establish a healthy environment for healing and to decrease the risk of potential infection. In severe injuries, it can help to determine whether or not a limb should be savaged or amputated. Underlying injuries to vital structures must be identified and repaired. Neurovascular injuries need to be repaired either primarily or with the use of shunts in cases of vascular injury and prolonged ischemia. Fractures must be identified, irrigated, debrided, and then stabilized with internal or external fixation. Tendon injuries should be repaired primarily, if possible, or prepared for more extensive future reconstruction as a staged procedure. All of these interventions will likely have bearing on postoperative rehabilitation and associated restrictions that therapists will need to be informed of to optimize outcomes. After repair of these underlying vital structures, soft tissue coverage becomes the next consideration. Soft tissue reconstruction options include primary closure, delayed primary closure, healing by secondary intention, skin grafting, local tissue transfer, free tissue transfer, or any combination of these techniques. The “reconstructive ladder” is a simple, metaphorical concept of these increasing levels of complexity and required skill that helps facilitate reconstructive options

2

(Fig. 80.1). By no means, though, is the reconstructive surgeon restricted to attempting the lower rungs of the ladder before using more advanced techniques of the higher rungs. This concept has been alternatively suggested as the “reconstructive elevator” with decision making being based on surgeon’s experience and specifics of the wound.

Primary Wound Closure

Primary wound closure simply involves approximating the wound edges. This is accomplished with the use of sutures, staples, tapes, or skin glue, as a single or multilayered repair. Delayed primary closure suggests a delay in the repair, such as waiting for associated edema to resolve sufficiently to allow for direct skin closure or to reassess soft tissue viability before closure. Delayed primary closure can be a useful technique for fasciotomy wounds after decompression of a muscle compartment. If motion at the joints adjacent to the wound might place tension forces on the incision or underlying musculoskeletal injury indicates, a custom fabricated orthosis may be considered. It is always important that such orthoses and dressings in general do not place excessive external compression on the incision or skin flaps.

Healing by Secondary Intention

Healing by secondary intention refers to leaving a wound open and allowing it to heal spontaneously through contraction and reepithelialization. Use of the method is based on wound size and whether or not there are exposed structures or hardware. In the hand and upper extremity, healing by secondary intention can be successfully applied to small wounds (with acceptable results) such as fingertip injuries involving less than a 1.5-cm defect, without exposed underlying bone. Healing of larger hand and upper extremity wounds by secondary intention, however, can result in significant scar formation and contracture, with subsequent limitations in range of motion (ROM) and function. Proper wound care should involve regular cleansing to prevent infection and to dislodge superficial debris along with the application of topical emollient to prevent wound desiccation.

Negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) uses a vacuum dressing changed in cyclical fashion to facilitate wound closure by removing blood and serous fluid, decreasing bacterial burden, and increasing microperfusion at the wound bed.

5

The porous “sponge” dressing achieves this while deforming the wound into a smaller shape. Some wounds treated in this manner can eventually reepithelialize completely when small enough or can be closed later with another method of reconstruction.

Skin Grafts

A skin graft is a harvested segment of epidermis and dermis that has been elevated and separated completely from its blood supply. The first reported transfer of skin was credited to Reverdin in 1870,

6

but skin grafting did not become common until the invention of the dermatome by Padget

7

during World War II. The dermatome simplified the method of elevating a skin graft, providing a reliable instrument for consistently harvesting a graft of a desired size and depth. The dermatome remains the primary tool used today for harvesting skin grafts. With the increased use of skin grafts, it was recognized that their early use for wound coverage could retard the extent of wound contracture, thus limiting deformity and functional disability.

8

Skin grafts can either be full thickness or split thickness. All skin grafts heal by a well-studied progression of vascular perfusion whereby nourishing blood vessels will grow from the wound bed through the dermis of the graft. These phases are referred to as plasmatic imbibition, inosculation, and neovascularization.

8

A full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) is a segment that includes the epidermis and entire dermis. An FTSG resembles normal skin more closely, including texture, color, and potential for hair growth. Am FTSG demonstrates the greatest amount of primary contracture but the least amount of secondary wound contracture. That is, after the harvest of an FTSG, it quickly contracts and appears much smaller because of the abundance of elastin fibers in the dermis. However, when the full-thickness graft is applied to a wound defect early, it maintains its size and can significantly limit contracture of the wound.

Full-thickness skin grafting do have limitations though. Given its thickness that blood vessels must traverse to support its “take,” there is a slightly greater risk of nonadherence of the graft. Additionally, donor site availability must be considered before full-thickness skin harvest. The donor site of an FTSG must be amenable to primary closure, or the created donor defect may require an additional skin grafting, local flap, or other means of coverage.

A split-thickness skin graft (STSG) consists of the entire epidermis and a variable portion of the dermis, most often harvested currently with a mechanical dermatome. An STSG has less primary contraction at harvest but is susceptible to more secondary contraction as the wound matures with healing. Increasing the thickness of the dermal component impedes secondary contraction but also increases risks of nonadherence as previously explained. STSGs typically do not contain sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and hair follicles in their thin dermis. As a result, the healed graft will be often dry, brittle, and hairless as opposed to FTSGs, which contain these structures.

An STSG can be either meshed or unmeshed. STSGs are typically meshed at ratios ranging from 1:1 to 3:1, with the ratio selected depending on the size of the defect needed to be grafted and the skin available for grafting. Meshing of the harvested skin graft facilitates expansion of the graft for coverage of more extensive wound defects. An STSG also may be left unmeshed and used to cover a wound as a sheet graft. A sheet graft avoids the meshed-pattern scarring associated with meshed skin grafts, thus resulting in a better aesthetic appearance.

Skin grafts may be secured to the margins of the wound with sutures, staples, tape, or skin glue. After the graft has been secured, the wound dressing and the postoperative management take precedence for the survival of the transferred skin graft. Various potential postoperative complications can lead to the demise of a skin graft. The best method for avoiding graft failure is prevention through meticulous postoperative management. The number one reason for failure of a skin graft is hematoma or seroma beneath the graft, thereby interfering with the delicate stages of skin graft healing and leading to loss of graft. Shearing of the skin graft can disrupt the fragile, early vessels supporting the graft. Prevention includes assuring hemostasis and application of well-placed postoperative dressings. Dressings over a skin graft must provide lubrication to prevent desiccation, appropriate compression to eliminate the potential space between the skin graft and the wound bed, and local immobilization to prevent shearing of the graft. This is best achieved by placing a lubricating (petrolatum) gauze such as Adaptic or Xeroform directly over the skin graft followed by cottonoid layering saturated in mineral oil. Securing these layers is essential to prevent shear and can be achieved by multiple means such as staples, circumferential dressing, tie-over bolster, or NPWT via vacuum-assisted dressing. Concave wounds often require a tie-over bolster to compress the graft evenly into the wound bed. Postoperative immobilization of nearby joints might be necessary to enhance skin graft adherence by preventing shear.

Postoperative Follow-up and Management

The dressing over an upper extremity skin graft typically is removed in 4 to 7 days, and the wound is reevaluated. By this time, the skin graft should be adherent to the wound bed, but continued wound care is still required to protect the reconstruction. It remains important to maintain a moist and lubricated environment to prevent the persistent risk of desiccation of the skin graft and to facilitate complete healing. This is accomplished with either continued wet-to-wet dressing changes or the application of a lubricating agent such as an antibacterial ointment (e.g., bacitracin) or other petroleum-based emollient. Typically, normal hygiene practices can resume with caution against scrubbing of the graft. After epithelialization of the skin graft is recognized, serial application of a moisturizing cream, such as Eucerin or the equivalent, in combination with gentle massage, can be initiated to facilitate progressive contoured scar maturation with flattening of the grafted surface and improve the overall cosmetic results. Rehabilitation of the upper extremity can then often be and advanced depending on the associated neurovascular, tendon, and bone injuries.

Management of the Skin Graft Donor Site

There are various methods for skin graft donor site management. Donor sites from FTSGs are treated as any other primarily closed incision. The donor site of an STSG has exposed dermis with sensitive nerve endings and is moist in the early period. Occlusive dressings such as OpSite (Smith and Nephew) or Tegaderm (3M Medical) can be applied at time of harvest to contain fluid production. Nonocclusive options include application of petroleum-impregnated dressing, such as Xeroform, at time of harvest and allowing it to desiccate as a “pseudo-eschar” until reepithelialization occurs. Reepithelialization of the graft donor site typically occurs in approximately 1 to 2 weeks. If fluid collects beneath the dressing, it is simply drained with a needle and the dressing patched with an additional OpSite, or the entire dressing is changed. After complete reepithelialization of the donor site, dressings are discontinued, and the healing bed can be treated for dryness as needed, using a moisturizing lotion such as Eucerin or an equivalent. Discoloration of the STSG donor site is common and should be protected with sunscreen. An STSG donor site can be reharvested in the future after epithelization has occurred, typically if all other donor sites are harvested or unavailable.

Skin Substitutes

Multiple dermal skin substitute products are commercially available to assist in wound coverage.

9

Acellular dermal matrices are available as allograft from human cadavers (i.e., Alloderm; BioHorizons, Birmingham, AL) or xenograft from other species such as porcine (i.e., Strattice; Allergan, Madison, NJ). Bioengineered wound technologies are available as well that can assist in covering exposed bone, tendon, and neurovascular structures. The most commonly used synthetic skin substitute is Integra Dermal Regeneration Template (Integra LifeSciences, Plainsboro, NJ), which is a bilayer composed of a protective, removable silicone layer and a scaffold layer of bovine collagen and chondroitin sulfate. All of these products allow for neovascularization and ultimately incorporation into the recipient wound bed.

9

Secondary skin grafting may be necessary after a mature, vascularized wound bed is achieved with coverage of underlying structures.

Postoperative management of skin substitutes is similar to that of skin grafts. Dressings are used to prevent shear and disturbance of early angiogenesis. Orthoses may be used to help stabilize and minimize disruption of the wound. Topical ointments or moist gauze is often used to prevent desiccation of these products along with surveillance for infection.

Local Tissue Transfer

Skin grafts are not appropriate for all wounds. When traumatic defects of the upper extremity involve significant soft tissue loss, a more complex reconstructive approach is required. These wounds typically involve exposure of underlying vital structures such as blood vessels, nerves, tendons devoid of paratenon, bones stripped of periosteum, or wounds with insufficient vascularity to support a skin graft. The next step in the algorithmic approach to reconstruction of the upper extremity, is of local, vascularized tissue.. Local tissue transfer refers to the dissection, elevation, and transfer of skin, combined with a varied amount of underlying tissue, potentially including subcutaneous tissue, fascia, muscle, nerve, tendon, and occasionally bone. During the elevation of a local tissue flap, the local blood supply supporting

the flap is preserved. This undivided portion of the flap containing the vascularity required for flap survival is labeled the pedicle. The pedicle contains an artery and its respective venae comitantes. A local flap can close a local tissue defect, establishing a well-vascularized, healthy environment to potentiate healing of the associated underlying injuries. Local tissue flaps are labeled according to the layers of tissue used, the pattern of the blood supply, and the type of mobilization required.

Skin Flaps

Using a local skin flap for reconstruction of an upper extremity defect refers to transferring adjacent skin and subcutaneous tissue into a wound to supply coverage and closure. A skin flap design is based on the local vascular anatomy of the skin and its type of movement. An axial pattern flap is a single-pedicle skin flap with an anatomically established arteriovenous system along its longitudinal axis.

10

An island flap is an axial pattern flap in which the skin bridge has been separated, leaving only the vascular pedicle intact at the base much like a balloon on its string.

10,11

For historical relevance, a random pattern flap referred to local skin flap without a specifically named arteriovenous system. This term is now archaic because we now know that all viable flaps require some sort of vascular anatomy. Perfusion of specific tissue territories by axial vessels throughout the body have been identified and labeled as angiosomes.

12

On an even smaller scale, individual perforating vessels from these larger vessels supply a finite tissue territory now known as perforasomes.

13

Skin flaps are also classified by mobilization techniques: rotation, advancement, and transposition. Rotation flaps pivot around a fixed point in a planned arc to reach a wound defect (Fig. 80.2). An advancement flap advances from the donor site to the recipient wound bed in a unidirectional vector without any rotation (Fig. 80.3). Transposition flaps move laterally and sometimes over an intervening peninsula of

intact skin. Numerous accounts of local flaps are well described in the literature; local flaps are traditionally valuable and versatile options in the reconstruction of many upper extremity defects at all levels: the fingers, hands, forearm, and upper arm.

Digital Reconstruction

Fingertip injuries involving a surface area of less than 1.5 cm, without exposure of bone or vital structures, can be allowed to heal by secondary intention with proper wound care. Moist dressings should be applied until the wound has reepithelialized. In fingertip injuries involving a surface area defect greater than 1.5 cm or digital defects with exposed underlying vital structures, a soft tissue reconstruction is often needed. The reconstructive goal is to achieve wound closure and restore digital sensibility. The selection of a particular surgical procedure is individualized to the patient based primarily on the wound size, location of the wound defect, adjacent tissue injury, and specific digit.

V-Y Advancement Flap

The volar V-Y

14–16

or lateral V-Y

17

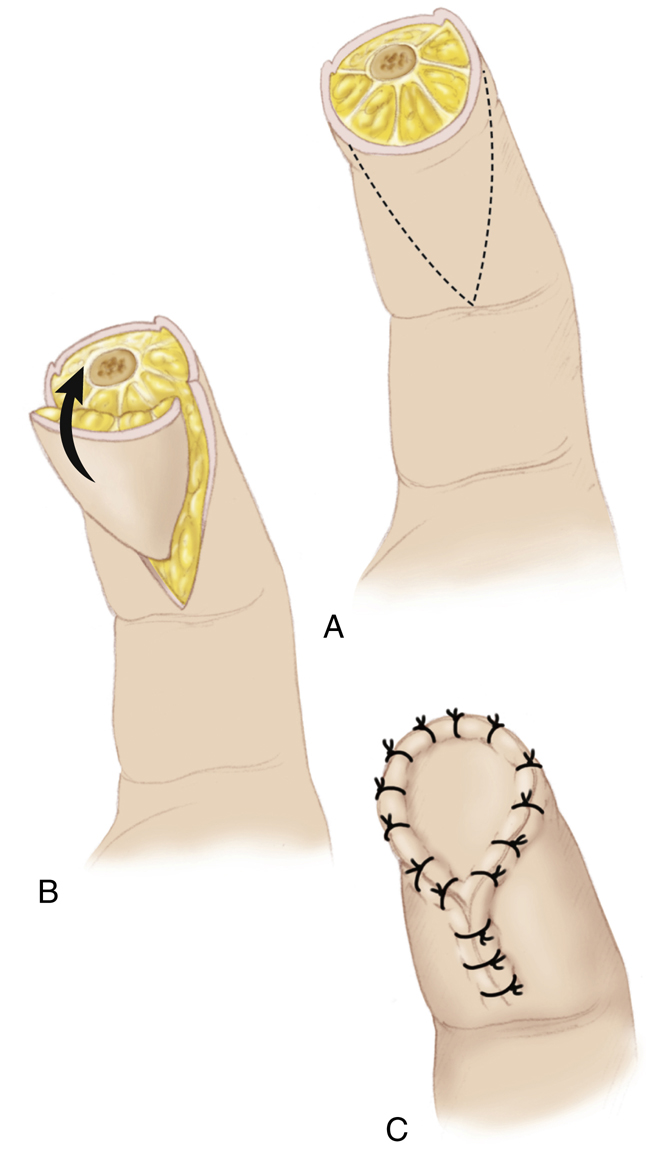

advancement flaps are skin flaps indicated for small fingertip injuries. These flaps offer a reconstructive dimension of 1 to 1.5 cm. After appropriate debridement of the injured tissues, the volar V-Y flap is created by making an apex-proximal triangular skin incision(s) just below the defect. The subcutaneous tissue is preserved, and the fibrous septae from the pulp to the periosteum are released. The dissected V-shaped flap is then advanced distally to cover the defect and subsequently closed in a Y-pattern with sutures (Fig. 80.4).

Volar Advancement Moberg Flap

Defects of the pulp of the thumb too large for coverage with a V-Y advancement flap may be closed using a Moberg flap. Moberg’s volar advancement flap may be advanced a distance of 1.5 to 2.0 cm and used to cover a traumatic defect involving the entire volar surface of the thumb.

18

This flap is based on both radial and ulnar neurovascular bundles that are unique to the thumb, which has additional dorsal blood supply. The Moberg flap is created by making midlateral incisions below the fingertip defect. The neurovascular bundles are preserved within the flap design, and the volar flap is then mobilized and advanced distally to cover the defect (Fig. 80.5). This is a reliable, sensate flap that restores sensibility to the pulp. Multiple modifications have been described to aid in mobility, including adding a proximal back cut and even creating an island flap known as O’Brien modification.

Cross-Finger Flaps

A cross-finger flap relies on tissue being transferred from an adjacent digit. The process of inosculation allows growth of new blood vessels from wound bed into the transferred flap. A conventional cross-finger flap uses an elevated skin flap from the dorsal aspect of one finger to cover an open volar or tip wound with exposed tendon or bone of an adjacent finger.

19

The donor site is then covered with a skin graft (Fig. 80.6). A reverse cross-finger flap requires dissecting an additional adipofascial flap beneath the full-thickness skin flap. The adipofascial flap is used to cover a dorsal wound defect of an adjacent finger.

20

The full-thickness skin flap is then reinset over the donor defect and a skin graft is placed over the transferred adipofascial flap on the dorsal surface of the reconstructed digit. Each of these flaps can cover a digital defect up to 2 cm. Additional soft tissue injury to adjacent digits may preclude the use of a cross-finger flap.

Postoperative care for the skin graft is based on principles previously described in this chapter. Caution is emphasized to the patient while the two digits are “attached” by the skin flap, often protected by bulky dressing or an orthosis. After a period of 2 to 3 weeks after the first stage, the flap is then divided at its base of the donor digit and inset

in to the reconstructed digit. Hand therapy is initiated early to maintain optimal ROM and function.

Digital Island Flaps

Digital island flaps are excellent reconstructive tools for covering either distal or proximal digital defects up to 2.5 cm, overlying exposed joints or tendons (Fig. 80.7). A skin flap is created in a pattern indicated by the local defect and then harvested based on the proper digital artery and vein.

21

The associated proper digital nerve can be included to add sensibility to the reconstructed flap or preserved in its natural anatomic state. These flaps can be based on anterograde blood flow of the digital artery or even retrograde flow from the other digital artery of the digit crossing bridging vessels, known as a reverse digital island flap. Homodigital island flaps are based on the donor site from the same digit, whereas heterodigital island flaps are transferred from an adjacent digit. The flap is secured in to place, and the donor site is usually reconstructed with a small FTSG.

Postoperative Management of Local Tissue Flaps for Digital Reconstruction

For these various flaps used to reconstruct digits, the wounds are covered with a nonconstricting, nonadherent dressing and often further protected with an overlying orthosis, such as cap splint. These flaps are monitored for viability, swelling, and venous congestion. After 2 weeks, sutures are usually removed, and motion can be initiated depending on associated bone or tendon repairs. After the wound has achieved stable healing, additional modalities for edema control and desensitization may be added to the therapy regimen.

Muscle, Musculocutaneous, and Fasciocutaneous Flaps

Muscle, musculocutaneous, and fasciocutaneous flaps are more complex reconstructive procedures used for full-thickness wound defects of the upper extremity. If vital structures, such as tendons, blood vessels, nerves, and bone, are exposed, these injuries require vascularized soft tissue coverage to optimize healing. Additionally, hardware for fracture fixation or joint implants is susceptible to bacterial biofilms and must be protected with vascularized soft tissue.

These flaps can be designed with variable layers of tissues dictated by the wound defect and reconstructive needs. Size limitations of particular flaps can preclude their use for certain defects. For wounds that have partial areas without exposed structures, flap reconstruction can be combined with other techniques previously described such as skin grafts. Muscle, musculocutaneous, and fasciocutaneous flaps, either harvested and used as local flaps or as free tissue transfers, can provide sufficient healthy tissue bulk to cover and fill large wound defects. These soft tissue flaps are based on reliable vascular anatomy and are versatile tissue transfers.

20

Muscles transferred with their motor innervation can even be used for reanimation of function. The upper extremity offers several excellent choices for local tissue transfers.

Postoperative Management of Local Tissue Flaps

At the time of the operation, the local tissue flap is protected with a sterile dressing and a supportive orthosis at the appropriate joint level. A “window” is often cut out of the dressing over the created flap to allow direct visualization of the reconstruction in the immediate postoperative period. This allows for clinical observation of the tissue vascularity, which is monitored by color, skin turgor, and capillary refill. Pallor or delayed capillary refill may represent lack of arterial blood flow within the flap, whereas darkened discoloration or brisk capillary refill suggests venous congestion. Each of these clinical findings suggests potential flap failure and the need for surgical reexploration and revision. Postoperatively, the reconstructed upper extremity is elevated on a couple of pillows or a prefabricated foam wedge commercially designed for limb elevation. Elevation is of utmost importance to prevent upper extremity swelling, which increases pressure on compressible veins, thereby decreasing venous outflow and leading to congestion. The tissue pressure seen as venous congestion can overwhelm arterial inflow and microvascular perfusion, leading to thrombosis or cell death. Upon discharge home, elevation is continued, and orthoses are left intact to maintain support and protection, facilitating complete healing of the reconstruction.

Indwelling drains are used to eliminate fluid, which can add pressure on the flap and incisions. The patient or a home health care agency can monitor operative drains at home, where output is measured and recorded over 24-hour periods. The drains are removed at clinic follow-up when the reported output falls below a minimum volume determined by the surgeon over a 24-hour period. Sutures or staples are removed at approximately 2 weeks postoperatively, and an early rehabilitation protocol is instituted to facilitate functional restoration. The intensity and timing of the postoperative rehabilitation therapy depend on the extent and specific nature of the structural injuries.

During the first few weeks of recovery, new blood vessels are growing from the underlying wound bed into the flap. Eventually, the perfusion of the flap is not solely provided by the vascular pedicle that allowed its initial transfer. Such flaps can often be reliably reelevated for debulking or secondary stages of reconstruction within a few months. Cognizance of the pedicle remains important and avoidance of its division is desirable when possible.

Free Tissue Transfer

Reconstruction of an upper extremity wound defect using a local regional tissue flap is not always feasible. Local tissue transfer may be limited because of the wound location, defect size, or regional donor site deficiencies. A vascular pedicle may not be long enough to reach a particular defect, or the defect may be too large to cover completely with local tissue. In these instances, the reconstructive surgeon looks to the highest rung of the reconstructive ladder, free tissue transfer.

Autologous free tissue transfer or free flap refers to the transplant of tissue from one location of the body to another. This is achieved by using an operating microscope and techniques of microsurgery to perform small-vessel anastomoses between the pedicle of the transferred free tissue flap and the prepared local recipient vessels near the defect site.

Microsurgery for extremity reconstruction began almost 6 decades ago with the introduction of the operating microscope for anastomoses of blood vessels, described by Jacobson.

22

The operating microscope was first used to repair injured digital arteries, which began the age of digital replantation in the 1960s.

23,24

In the 1970s, the use of the microscope was expanded to microsurgical composite free tissue transplantation.

25

Composite free tissue transplantation is the harvesting and transfer of a composite (or collection) of tissues, including muscle, fascia, skin and subcutaneous tissue, nerve, tendon, bone, or any combination of these. The vascular inflow and outflow of the harvested free tissue flap is preserved for anastomosis with the local blood supply. Efforts of the modern microsurgeon have expanded from just providing soft tissue bulk for coverage of a wound defect to the ultimate reconstructive goal of full functional restoration.

26

Free tissue transfer continues to play an increasingly vital role in the reconstruction of upper extremity complex wounds. Free tissue flaps, dissected as muscle, musculocutaneous, or fasciocutaneous flaps, can be harvested out of the zone of injury and transferred to a distant extensive wound, providing healthy tissue for coverage and optimizing the healing potential. Free tissue transplantation offers many advantages, primarily including early mobilization and rehabilitation. Free flaps also offer the possibility of using composite free tissue transplantation, as a single-stage procedure, even in the emergency setting.

27

Free muscle flaps can provide potential restoration of specific upper extremity motor function and sensibility.

34

For example, after Volkmann’s contracture of the forearm, flexion of the fingers is lost because of the ischemic injury associated with this local traumatic event. In this instance, a free functional muscle such as gracilis muscle may be harvested with its motor nerve and transferred as an innervated free muscle flap to restore finger flexion. Similarly, an innervated latissimus dorsi free muscle flap may be used to restore elbow flexion in individuals lacking elbow function secondary to traumatic injury or congenital anomaly. A cutaneous sensory nerve also may be preserved with a harvested free fasciocutaneous flap and used to create a neurosensory flap, potentially restoring sensibility to a particular area. Free tissue reconstruction also allows for transfer of whole or partial toes to the hand for restoration of functional grasp and pinch.

Numerous excellent free flaps are available for reconstruction of upper extremity wound defects, each indicated by the size and deficiencies of the particular wound. Several muscle, musculocutaneous, and fasciocutaneous flaps can be used for either local tissue transfer or as free flaps for upper extremity reconstruction, including the radial forearm flap, lateral arm flap, parascapular and scapular flaps, and the latissimus dorsi flap.

Postoperative Management of Free Flaps

After free tissue transfer, the free flap is protected with sterile dressings and a supportive orthosis with care to prevent any pressure on the vascular pedicle and anastomoses. A window in the dressing is created over the reconstruction to allow for meticulous postoperative clinical observation. Physical examination includes flap color, skin turgor, capillary refill, and surface Doppler signals for arterial and venous flow. Additional technologies are available for flap monitoring. Commercially available implantable Doppler devices are placed on the vascular pedicle and allow for instantaneous audible assessment of flow through the vessels. Another device monitors continuous skin oxygenation through a skin surface probe on the flap island and allows for trending data and abrupt disruptions in perfusion. Loss of the signal suggests vascular compromise and impending failure of the free flap unless addressed expeditiously in the operating room. Thrombosis of either venous or arterial anastomoses that is recognized early can undergo emergent thrombectomy and revision of anastomosis with potential salvage of the free flap. The most reliable method of accurate free flap monitoring remains clinical observation and physical assessment.

Donor sites are often closed primarily but occasionally require skin grafting or adjacent tissue transfer. Additionally, harvest of bone, such as fibula or medial femoral condyle, may require assistive devices for walking, gait training, or orthoses in the short term. Depending on the underlying injuries to vital structures, such as tendons or bone, early rehabilitation, including occupational therapy and social reintegration, can now be initiated. Neovascularization occurs as well in the weeks after free flap reconstruction and allows for reliable re-elevation for additional reconstructive procedures or further contouring of the flap at a later stage.

Common Flaps for Reconstruction of the Upper Extremity

Radial Forearm Flap

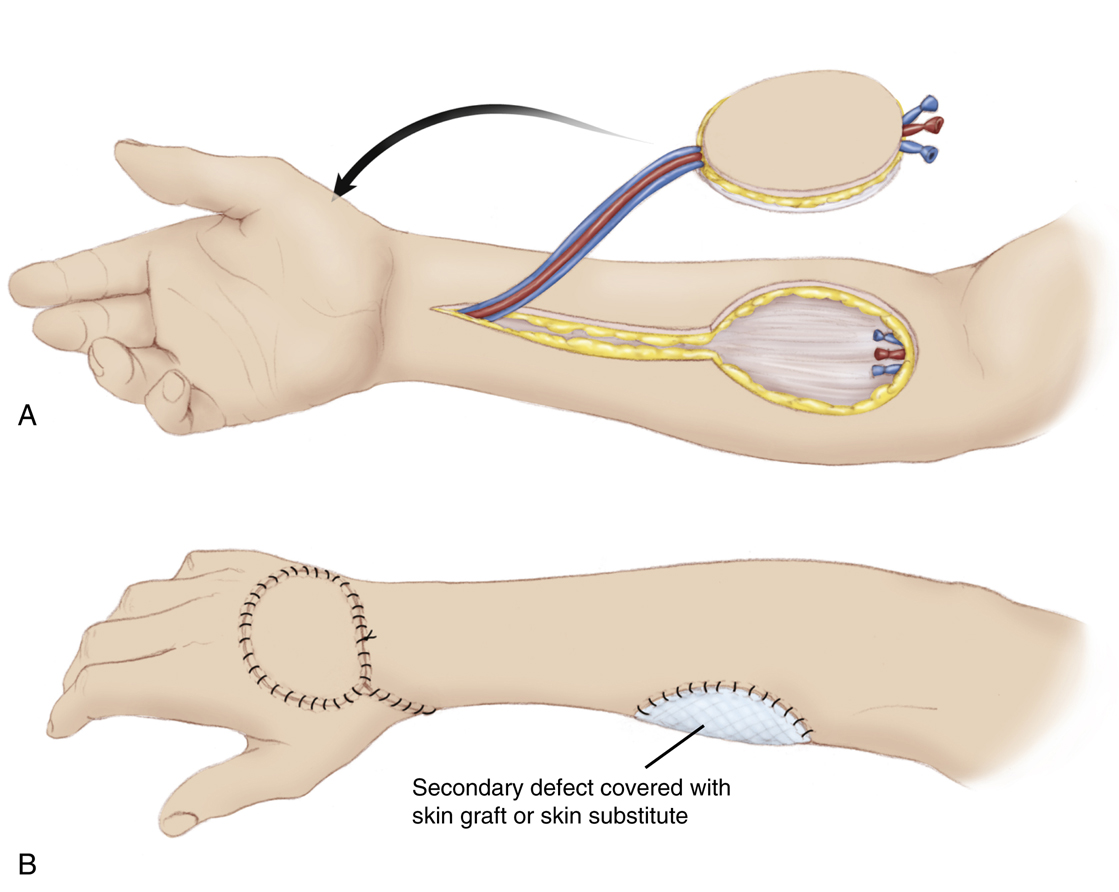

The radial forearm flap is a fasciocutaneous flap harvested from the volar forearm based on the radial artery and concomitant veins

28

(Fig. 80.8). This flap offers the reconstructive surgeon an excellent option for coverage of defects requiring thin, pliable tissue. The radial forearm flap can be raised on its pedicle and rotated locally. When based on antegrade flow, it can be rotated to cover forearm or elbow defects. When based on retrograde flow, the reverse radial forearm can cover hand and wrist wounds. Additionally, this flap can be harvested as a free flap or combined with the palmaris longus tendon or part of the brachialis tendon for associated tendon reconstruction, a portion of the radius for bony reconstruction,

29

or the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve to establish an innervated sensate flap. A variation of this flap harvest is the use of the antebrachial fascia only to provide a gliding surface or closure of a wound. The disadvantages of this procedure are the sacrifice of a major forearm artery, and the unsightly donor harvest site, which often requires a skin graft for coverage for sizeable skin paddles. An Allen’s test should be performed before the procedure and temporary occlusion of the radial artery should be performed intraoperatively before division of the artery using a microvascular occluding clamp to ensure adequate hand perfusion from the ulnar artery.

Posterior Interosseous Flap

The posterior interosseous flap is a fasciocutaneous flap that can be used as a reverse pedicled local tissue transfer based on the posterior interosseous artery, which is located between the extensor carpi ulnaris and extensor digiti minimi. It can be used to cover distal defects of the wrist, dorsal hand, and first webspace. A reconstructive dimension of 8 × 15 cm may be elevated and rotated, but any skin island greater than 4 cm wide requires a skin graft for closure of the donor site. This flap is dissected and harvested

from the proximal dorsal forearm, rotated distally, and secured into the defect. Preservation of major arteries to the hand is a significant advantage of this flap. A disadvantage of this flap is hair growth on the skin island, which may be problematic for palmar reconstruction. One must be cognizant of the location of the posterior interosseous nerve and be careful to avoid injury to this nerve.

Lateral Arm Flap

The lateral arm flap is an excellent flap for reconstruction of upper extremity soft tissue defects. This flap can be used as a local pedicled flap or free flap based on antegrade flow through the posterior radial collateral artery. Retrograde flow through interosseous recurrent artery at the distal humerus allows for rotation of a reverse lateral arm flap to cover elbow and proximal forearm wounds. The lateral arm flap can be harvested as an innervated cutaneous flap with a reconstructive dimension of up to 15 × 18 cm. It may be harvested as an osteocutaneous flap using a portion of the lateral column of the humerus and may include a fasciocutaneous forearm extension for additional surface area or a tendon strip from the triceps, depending on the individual needs for reconstruction.

30

As a free flap, the lateral arm flap may be further used for coverage of defects involving the dorsum of the hand or the first webspace after contracture release.

Groin Flap

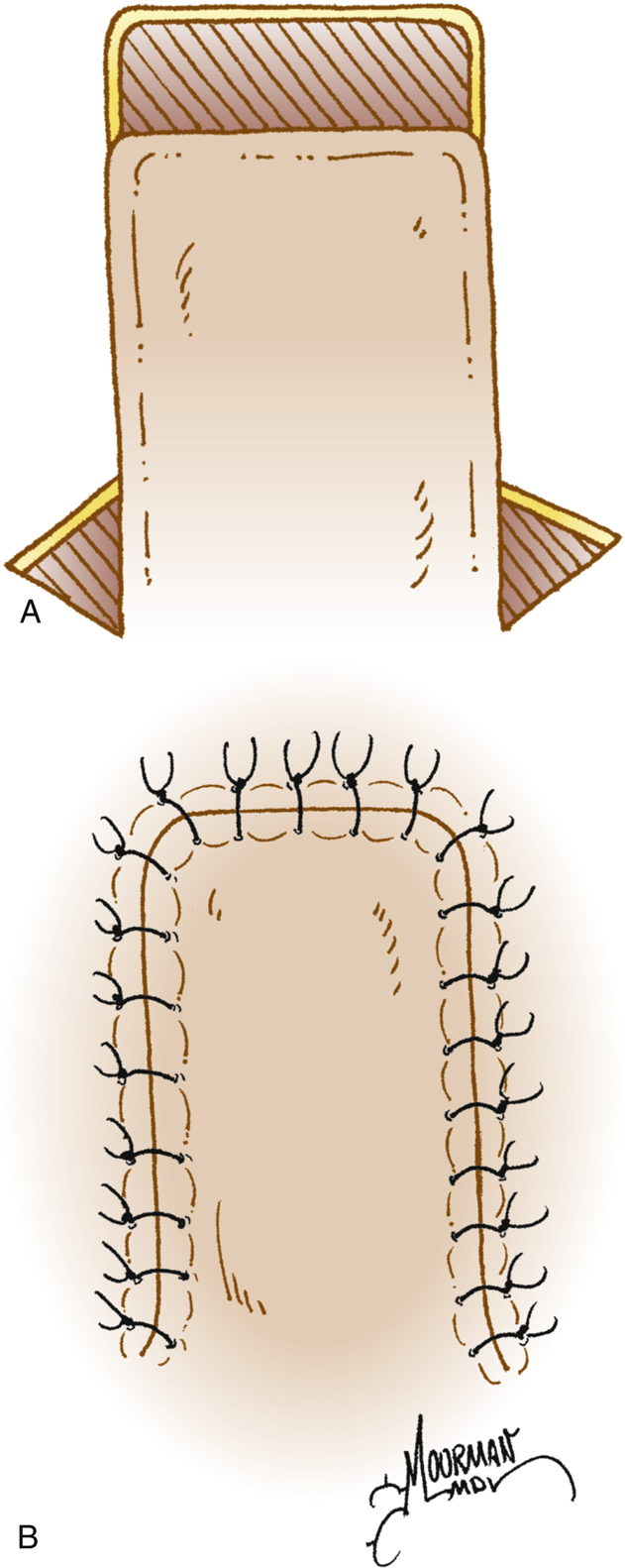

The groin flap is an axial pattern flap that provides a reliable surgical option for reconstruction of distal upper extremity injuries. This flap is most often elevated as a pedicle flap based on the superficial circumflex iliac artery and concomitant veins and then used to cover either hand or forearm defect

31

(Fig. 80.9). The donor defect may close primarily, or it may require a skin graft for coverage depending on the size. The arm is brought in proximity to the groin to allow for inset of the flap into the defect. After the flap is secured to the defect, the upper extremity must be immobilized to eliminate tension on the vascular pedicle. Immobilization of the flap may be achieved with circumferential dressings, tape, or supportive orthoses and carefully maintained as an outpatient.

The patient then returns in approximately 3 weeks for surgical division of the vascular pedicle at the torso and final contouring and insetting of the flap. Before division of the flap, gentle ROM of the uninvolved digits should be performed. Shoulder and elbow stiffness can be seen as a result of this flap and associated immobilization but often responds to therapy after division of the flap from the groin.

This flap can also be harvested as a free flap based on the superficial circumflex iliac perforator, known as an SCIP flap, and offers another choice of thin, pliable fasciocutaneous reconstruction.

Parascapular and Scapular Flaps

The parascapular and scapular flaps are cutaneous flaps based on a branch of the circumflex scapular artery of the posterior shoulder

32

(Fig. 80.10). Each of these flaps has a reconstructive dimension of about 10 × 25 cm. A parascapular or scapular flap can be rotated locally and used as a pedicled flap for coverage of shoulder or proximal, posterior arm defects. This flap can be harvested and transplanted as free flap for coverage of both forearm and dorsal hand defects.

33

Parascapular and scapular flaps also provide the reconstructive surgeon the opportunity to incorporate additional fascial extensions to provide gliding surfaces for associated tendon repairs, if necessary, or include a portion of scapular bone for reconstruction of segmental forearm defects.

Latissimus Dorsi Flap

The latissimus dorsi flap is an excellent reconstruction option for the coverage of large surface area defects. This flap may be harvested as a muscle only or musculocutaneous flap and used as a pedicled tissue transfer to cover significantly large local defects of the shoulder and upper arm or as a free flap to cover extensive distal upper extremity wounds. The latissimus dorsi flap is harvested based on the thoracodorsal artery and concomitant vein

34

and contoured to fit the defect (Fig. 80.11). The thoracodorsal nerve can be harvested as well for functional animation of this muscle after transfer, both pedicled for elbow flexion or coapted to a donor motor nerve elsewhere. This flap has a very large surface area of up to

20 × 35 cm, depending on the size of the individual and amenable to immediate skin grafting at the reconstruction site. Fluid accumulation or seroma at the donor site can be seen, and therefore drains are often used until well healed. Functional deficits after latissimus dorsi harvest are minimal for most patients except potentially for those in overhead athletics or with bilateral harvest of muscles.

Serratus Muscle and Fascial Flap

The serratus flap is harvested as a muscular or fascial flap with or without a skin island based on the serratus vascular arcade originating from the subscapular artery. This flap has a reconstructive dimension of about 10 × 18 cm and provides the reconstructive surgeon with another versatile option for repairing upper extremity defects requiring thin pliable tissue or gliding tissues for associated tendon reconstructions. Vascularized ribs may be harvested with this flap for additional bony reconstruction. Multiple slips of muscle can be neurotized by the long thoracic nerve for functional animation as well.

35

Temporoparietal Fascial (TPF) Flap

The temporoparietal fascial flap (TPF) consists of thin, supple fascia, harvested as a free flap, based on the superficial temporal artery and vein for the scalp

36,37

(Fig. 80.12). This flap has a reconstructive dimension of 8 × 15 cm and is often used for defects of the dorsal hand, palm, and digits. The TPF flap conforms nicely to the contour of a wound surface but requires the addition of a skin graft for completion of the surface coverage. Appropriate dressings are required for maintenance of a moist environment to facilitate skin graft survival and healing.

Gracilis Flap

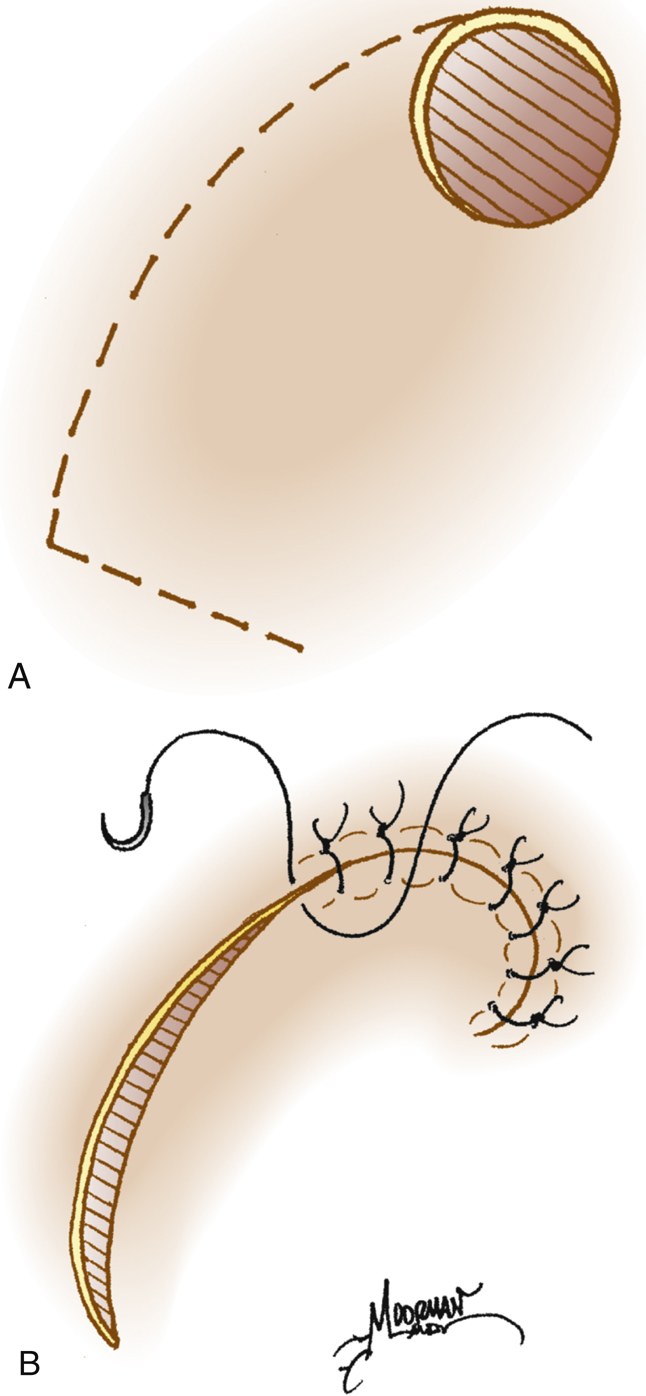

The gracilis flap can be harvested as a muscle or musculocutaneous flap and transplanted to the upper extremity as a free tissue transfer. This flap is based on the terminal branch of the medial femoral circumflex artery and concomitant veins

38,39

and can be used to cover defects up to 6 × 25 cm. The gracilis muscle also can be harvested with a motor branch of the obturator nerve and used as an innervated free muscle flap to restore flexor function to the upper extremity

38

(Fig. 80.13). Common functional uses of the gracilis are reconstruction for Volkmann’s contracture to restore digit flexion and for brachial plexus injury to restore flexion or extension of the elbow or digits.

Fibula Flap

The fibula flap involves the harvest of bone, with or without a skin paddle or muscle, for reconstruction of segmental defects of the shoulder, humerus, radius, ulna, wrist, and metacarpal associated with soft tissue loss. Choice of stabilization is critical to assure reconstructive success. This flap is based on the peroneal artery and veins and can include a segment of fibula up to 26 cm.

40

The proximal and distal 6 cm of the fibula are preserved to maintain stability of knee and ankle. A skin island with a reconstructive dimension of 8 × 15 cm may be included based on septal perforators from the peroneal vascular pedicle (Fig. 80.14). The donor site may or may not require a skin graft for closure, depending on the size of the skin paddle harvested. Periosteum-preserving osteotomies can be made in the harvest bone to allow for multiple configurations of bony reconstruction.

Anterolateral Thigh Flap

The anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap allows for a large fasciocutaneous skin island based on the descending branch of lateral femoral circumflex artery.

41,42

Islands can be as large as 25 cm wide but would require skin grafting for closure of the donor site. For upper extremity reconstruction, the ALT flap is harvest as a free flap (Fig. 80.15). Vastus lateralis muscle may be included with the design of the flap to obliterate dead space. Additionally, local vascular anatomy of the donor site allows for potential inclusion of tensor fascia lata muscle, which can be useful for tendon reconstruction. Multiple perforator anatomy permits multiple separate skin islands as well for complex reconstruction involving more than one defect nearby.

Medial Femoral Condyle Flap

The medial femoral condyle flap provides a segment of corticocancellous from the medial leg based on the descending geniculate artery.

42

A small skin island for coverage or more often monitoring purposes

can be included with the flap. This flap has been used most commonly for scaphoid nonunion reconstruction as well as long bone nonunion including the clavicle and humerus and forearm. A variation of the flap allows for harvest of cartilage-bearing trochlea from the knee as well, known as the medial femoral trochlea flap. This flap requires free tissue transfer to the defect.

Summary

Advances in applied anatomy and therapy have expanded choices for reconstruction of the upper extremity. These advances have been facilitated by the addition of new flaps and the increasing use of functional free tissue transfer. Surgeons should use the reconstructive ladder or elevator

for the treatment of upper extremity wounds. The extent and severity of the wounds coupled with the functional needs of the patient and availability of required tissues elements directs the reconstructive surgeon to the most appropriate option(s). The reconstructive options, surgical techniques, and postoperative pearls described in this chapter are used daily in practice. They offer excellent reconstructive management strategies for facilitating healing and optimizing functional rehabilitation.