Chapter 6: Lower Limb

Contributions By Christopher I. Wertz, MSRS, RT(R), Contributors to Past Editions Dan L. Hobbs, MSRS, RT(R)(CT)(MR), Beth L. Vealé, BSRS, MEd, PhD,RT(R)(QM), and Jeannean Hall-Rollins, MRC, BS, RT(R)(CV)

Radiographic Anatomy

Distal Lower Limb

The bones of the distal lower limb are divided into the foot, lower leg, and distal femur (Fig. 6.1). The ankle and knee joints are also discussed in this chapter. The proximal femur and the hip are included in Chapter 7, along with the pelvic girdle.

FOOT

The bones of the foot are fundamentally similar to the bones of the hand and wrist, which are described in Chapter 4.

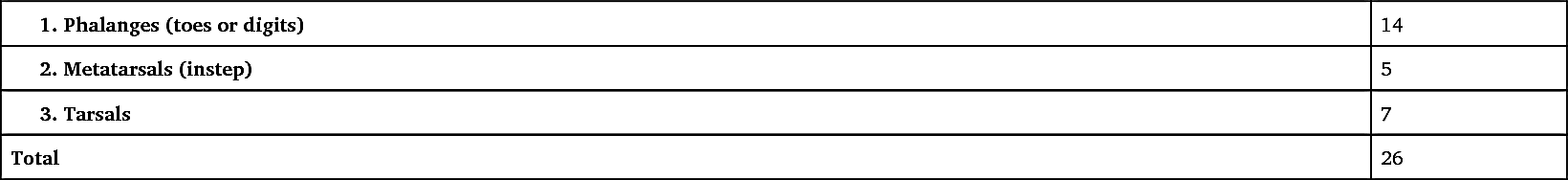

The 26 bones of one foot (Fig. 6.2) are divided into three groupsas follows:

|

1. Phalanges (toes or digits) |

14 |

|---|---|

|

2. Metatarsals (instep) |

5 |

|

3. Tarsals |

7 |

| Total | 26 |

Phalanges—Toes (Digits)

The most distal bones of the foot are the phalanges, which make up the toes, or digits. The five digits of each foot are numbered 1 through 5, starting on the medial or big-toe side of the foot. The large toe, or first digit, has only two phalanges, similar to the thumb: the proximal phalanx and the distal phalanx. Each of the second, third, fourth, and fifth digits has a middle phalanx, in addition to a proximal phalanx and a distal phalanx. Because the first digit has two phalanges and digits 2 through 5 have three phalanges apiece, 14 phalanges are found in each foot.

Similarities to the hand are obvious because there are also 14 phalanges in each hand. However, two noticeable differences exist: the phalanges of the foot are smaller, and their movements are more limited than those of the phalanges of the hand.

When any of the bones or joints of the foot are described, the specific digit and foot should also be identified. For example, referring to the “distal phalanx of the first digit of the right foot” would leave no doubt as to which bone is being described.

The distal phalanges of the second through fifth toes are very small and may be difficult to identify as separate bones on a radiograph.

Metatarsals

The five bones of the instep are the metatarsal bones. These are numbered along with the digits, with number 1 on the medial side and number 5 on the lateral side.

Each of the metatarsals consists of three parts. The small, rounded distal part of each metatarsal is the head. The centrally located, long, slender portion is termed the body (shaft). The expanded, proximal end of each metatarsal is the base.

The base of the fifth metatarsal is expanded laterally into a prominent rough tuberosity, which provides for the attachment of a tendon. The proximal portion of the fifth metatarsal, including this tuberosity, is readily visible on radiographs and is a common trauma site for the foot; this area must be well visualized on radiographs.

Joints of Phalanges (Digits) and Metatarsals

Joints of Digits

The joints or articulations of the digits of the foot are important to identify because fractures may involve the joint surfaces. Each joint of the foot has a name derived from the two bones on either side of that joint. Between the proximal and distal phalanges of the first digit is the interphalangeal (IP) joint.

Because digits 2 through 5 each comprise three bones, these digits also have two joints each. Between the middle and distal phalanges is the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. Between the proximal and middle phalanges is the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint.

Joints of Metatarsals

Each of the joints at the head of the metatarsal is a metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, and each of the joints at the base of the metatarsal is a tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint. The base of the third metatarsal or the third tarsometatarsal joint is important because this is the centering point or the central ray (CR) location for anteroposterior (AP) and oblique foot projections.

When joints of the foot are described, the name of the joint should be stated first, followed by the digit or metatarsal, and finally the foot. For example, an injury or fracture may be described as near the DIP joint of the fifth digit of the left foot.

Sesamoid Bones

Several small, detached bones, called sesamoid bones, often are found in the feet and hands. These extra bones, which are embedded in certain tendons, are often present near various joints. In the upper limbs, sesamoid bones are quite small and most often are found on the palmar surface near the metacarpophalangeal joints or occasionally at the interphalangeal joint of the thumb.

In the lower limbs, sesamoid bones tend to be larger and more significant radiographically. The largest sesamoid bone in the body is the patella, or kneecap, as described later in this chapter. The sesamoid bones illustrated in Figs. 6.3 and 6.4 are almost always present on the posterior or plantar surface at the head of the first metatarsal near the first MTP joint. Specifically, the sesamoid bone on the medial side of the lower limb is termed the tibial sesamoid and the lateral is the fibular sesamoid bone. Sesamoid bones also may be found near other joints of the foot. Sesamoid bones are important radiographically because fracturing these small bones is possible. Because of their plantar location, such fractures can be quite painful and may cause discomfort when weight is placed on that foot. Special tangential projections may be necessary to demonstrate a fracture of a sesamoid bone, as shown later in this chapter (p. 231).

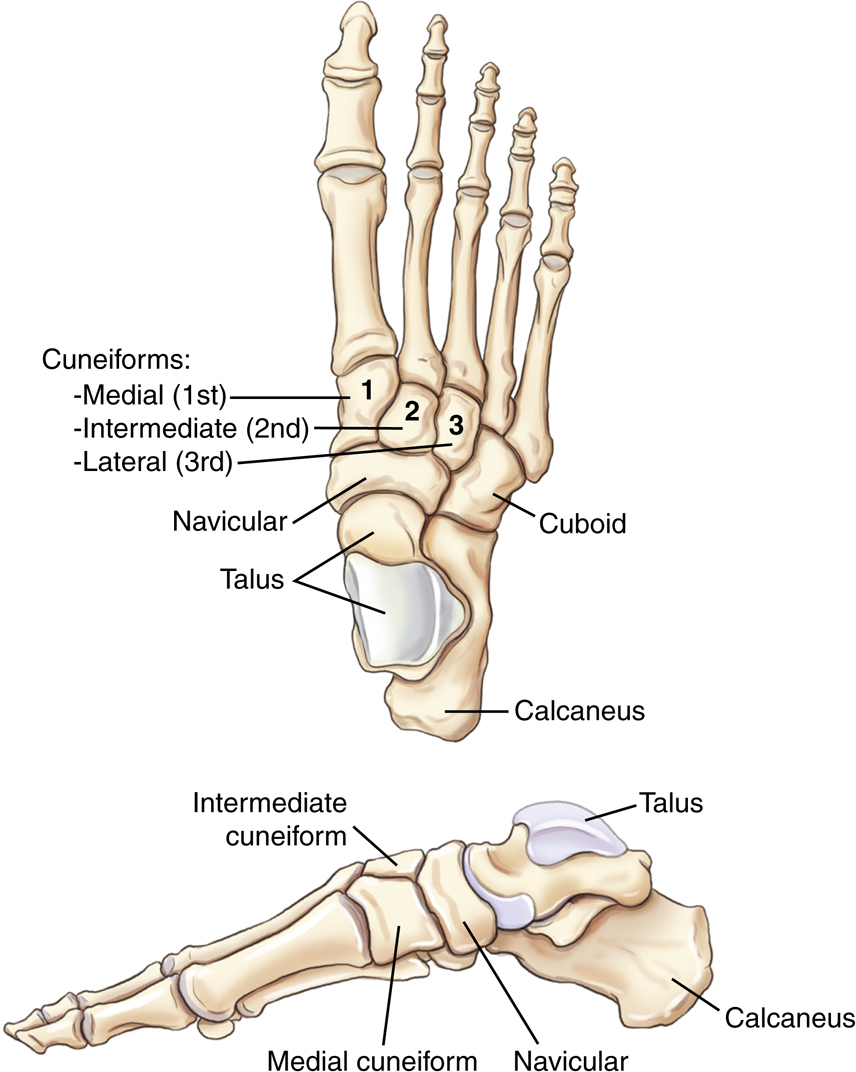

Tarsals

The seven large bones of the proximal foot are called tarsal bones (Fig. 6.5). The names of the tarsals can be remembered with the aid of a mnemonic: Come to Colorado (the) next 3 Christmases.

| (1) Come | Calcaneus (os calcis) |

|---|---|

| (2) To | Talus (astragalus) |

| (3) Colorado | Cuboid |

| (4) Next | Navicular (scaphoid) |

| (5, 6, 7) 3 Christmases | First, second, and third cuneiforms |

The calcaneus, talus, and navicular bones are sometimes known by alternative names: the os calcis, astragalus, and scaphoid. However, correct usage dictates that the tarsal bone of the foot should be called the navicular, and the carpal bone of the wrist, which has a similar shape, should be called the scaphoid. (The carpal bone more often has been called the navicular rather than the preferred scaphoid.)

Similarities to the upper limb are less obvious with the tarsals in that there are only seven tarsal bones, compared with eight carpal bones in the wrist. Also, the tarsals are larger and less mobile because they provide a basis of support for the body in an erect position, compared with the more mobile carpals of the hand and wrist.

The seven tarsal bones sometimes are referred to as the ankle bones, although only one of the tarsals, the talus, is directly involved in the ankle joint. Each of these tarsals is described individually, along with a list of the bones with which they articulate.

Calcaneus

The largest and strongest bone of the foot is the calcaneus (kal-kay′-ne-us). The posterior portion is often called the heel bone. The most posterior-inferior part of the calcaneus contains a process called the tuberosity. The tuberosity can be a common site for bone spurs, which are sharp outgrowths of bone that can be painful on weight bearing.

Certain large tendons, the largest of which is the Achilles tendon, are attached to this rough and striated process, which at its widest point includes two small, rounded processes. The largest of these is labeled the lateral process. The medial process is smaller and less pronounced.

Another ridge of bone that varies in size and shape and is visualized laterally on an axial projection is the peroneal trochlea (per″-o-ne′-al trok′-le-ah). Sometimes, in general, this is also called the trochlear process. On the medial proximal aspect is a larger, more prominent bony process called the sustentaculum (sus″-ten-tak′-u-lum) tali, which literally means a support for the talus.

Articulations

The calcaneus articulates with two bones: anteriorly with the cuboid and superiorly with the talus. The superior articulation with the talus forms the important subtalar (talocalcaneal) joint. Three specific articular facets appear at this joint with the talus through which the weight of the body is transmitted to the ground in an erect position: the larger posterior articular facet and the smaller anterior and middle articular facets. The middle articular facet is the superior portion of the prominent sustentaculum tali, which provides medial support for this important weight-bearing joint.

The deep depression between the posterior and middle articular facets is called the calcaneal sulcus (Fig. 6.6). This depression, combined with a similar groove or depression of the talus, forms an opening for certain ligaments to pass through. This opening in the middle of the subtalar joint is the sinus tarsi, or tarsal sinus (Fig. 6.7).

Talus

The talus, the second largest tarsal bone, is located between the lower leg and the calcaneus. The weight of the body is transmitted by this bone through the important ankle and talocalcaneal joints.

Articulations

Navicular

The navicular is a flattened, oval bone located on the medial side of the foot between the talus and the three cuneiforms.

Articulations

The navicular articulates with five bones: posteriorly with the talus, laterally with the cuboid, and anteriorly with the three cuneiforms (Fig. 6.8).

Cuneiforms

The three cuneiforms (meaning “wedge shaped”) are located on the medial and mid aspects of the foot between the first three metatarsals distally and the navicular proximally. The largest cuneiform, which articulates with the first metatarsal, is the medial (first) cuneiform. The intermediate (second) cuneiform, which articulates with the second metatarsal, is the smallest of the cuneiforms. The lateral (third) cuneiform articulates with the third metatarsal distally and with the cuboid laterally. All three cuneiforms articulate with the navicular proximally.

Articulations

The medial cuneiform articulates with four bones: the navicular proximally, the first and second metatarsals distally, and the intermediate cuneiform laterally.

The intermediate cuneiform also articulates with four bones: the navicular proximally, the second metatarsal distally, and the medial and lateral cuneiforms on each side.

The lateral cuneiform articulates with six bones: the navicular proximally; the second, third, and fourth metatarsals distally; the intermediate cuneiform medially; and the cuboid laterally.

Cuboid

The cuboid is located on the lateral aspect of the foot, distal to the calcaneus and proximal to the fourth and fifth metatarsals.

Articulations

The cuboid articulates with five bones: the calcaneus proximally, the lateral cuneiform and navicular medially, and the fourth and fifth metatarsals distally.

Arches of Foot

Longitudinal Arch

The bones of the foot are arranged in longitudinal and transverse arches, providing a strong, shock-absorbing support for the weight of the body. The springy, longitudinal arch comprises a medial and a lateral component, with most of the arch located on the medial and mid aspects of the foot.

Transverse Arch

The transverse arch is located primarily along the plantar surface of the distal tarsals and the tarsometatarsal joints. The transverse arch is primarily made up of the wedge-shaped cuneiforms, especially the smaller second and third cuneiforms, in combination with the larger first cuneiform and the cuboid (Fig. 6.9).

Box 6.1 presents a summary of the tarsals and articulating bones.

Ankle Joint

Frontal View

The ankle joint is formed by three bones: the two long bones of the lower leg, the tibia and fibula, and one tarsal bone, the talus. The expanded distal end of the slender fibula, which extends well down alongside the talus, is called the lateral malleolus.

The distal end of the larger and stronger tibia has a broad articular surface for articulation with the similarly shaped broad upper surface of the talus. The medial elongated process of the tibia that extends down alongside the medial talus is called the medial malleolus.

The inferior portions of the tibia and fibula form a deep “socket,” or three-sided opening, called a mortise, into which the superior talus fits. However, the entire three-part joint space of the ankle mortise is not seen on a true frontal view (AP projection) because of overlapping of portions of the distal fibula and tibia by the talus. This overlapping is caused by the more posterior position of the distal fibula, as is shown on these drawings. A 15° internally rotated AP oblique projection, called the mortise position,

1

is performed (see Fig. 6.15) to demonstrate the mortise of the joint, which should have an even space over the entire talar surface.

The anterior tubercle is an expanded process at the distal anterior and lateral tibia that has been shown to articulate with the superolateral talus, while partially overlapping the fibula anteriorly (Figs. 6.10 and 6.11).

The distal tibial joint surface that forms the roof of the ankle mortise joint is called the tibial plafond (ceiling). Certain types of fractures of the ankle in children and youth involve the distal tibial epiphysis and the tibial plafond.

Lateral View

The ankle joint, seen in a true lateral position in Fig. 6.11, demonstrates that the distal fibula is located about ⅜ inch (1 cm) posterior in relation to the distal tibia. This relationship becomes important in evaluation for a true lateral radiograph of the lower leg, ankle, or foot. A common mistake in positioning a lateral ankle is to rotate the ankle slightly so that the medial and lateral malleoli are directly superimposed; however, this results in a partially oblique ankle, as these drawings illustrate. A true lateral requires the lateral malleolus to be about (⅜) inch (1 cm) posterior to the medial malleolus. The lateral malleolus extends about ⅜ inch (1 cm) more distal than its counterpart, the medial malleolus (best seen on frontal view, Fig. 6.10).

Axial View

An axial view of the inferior margin of the distal tibia and fibula is shown in Fig. 6.12; this visualizes an “end-on” view of the ankle joint looking from the bottom up, demonstrating the concave inferior surface of the tibia (tibial plafond). Also demonstrated are the relative positions of the lateral and medial malleoli of the fibula and tibia. The smaller fibula is shown to be more posterior. A horizontal plane drawn through the midportions of the two malleoli would be approximately 15° to 20° from the coronal plane (the true side-to-side plane of the body). This positioning line is termed the intermalleolar plane. The lower leg and ankle must be rotated 15° to 20° to bring the intermalleolar plane parallel to the coronal plane. This relationship of the distal tibia and fibula becomes important in positioning for various views of the ankle joint or ankle mortise, as described in the positioning sections of this chapter.

Joint Structure

The ankle joint is a synovial joint of the saddle (sellar) type with flexion and extension (dorsiflexion and plantar flexion) movements only. This joint requires strong collateral ligaments that extend from the medial and lateral malleoli to the calcaneus and talus. Lateral stress can result in a “sprained” ankle with stretched or torn collateral ligaments and torn muscle tendons leading to an increase in parts of the mortise joint space. AP stress views of the ankle can be performed to evaluate the stability of the mortise joint space.

Review Exercise with Radiographs

Three common projections of the foot and ankle are shown with labels for an anatomy review of the bones and joints. A good review exercise is to cover up the answers that are listed here and identify all the labeled parts before checking the answers.

Lateral Left Foot (Fig. 6.13)

Oblique Right Foot (Fig. 6.14)

- A. Interphalangeal joint of first digit of right foot

- B. Proximal phalanx of first digit of right foot

- C. Metatarsophalangeal joint of first digit of right foot

- D. Head of first metatarsal

- E. Body of first metatarsal

- F. Base of first metatarsal

- G. Second or intermediate cuneiform (partially superimposed over first or medial cuneiform)

- H. Navicular

- I. Talus

- J. Tuberosity of calcaneus

- K. Third or lateral cuneiform

- L. Cuboid

- M. Tuberosity of the base of the fifth metatarsal

- N. Fifth metatarsophalangeal joint of right foot

- O. Proximal phalanx of fifth digit of right foot

AP Mortise View Right Ankle (Fig. 6.15)

Lateral Right Ankle (Fig. 6.16)

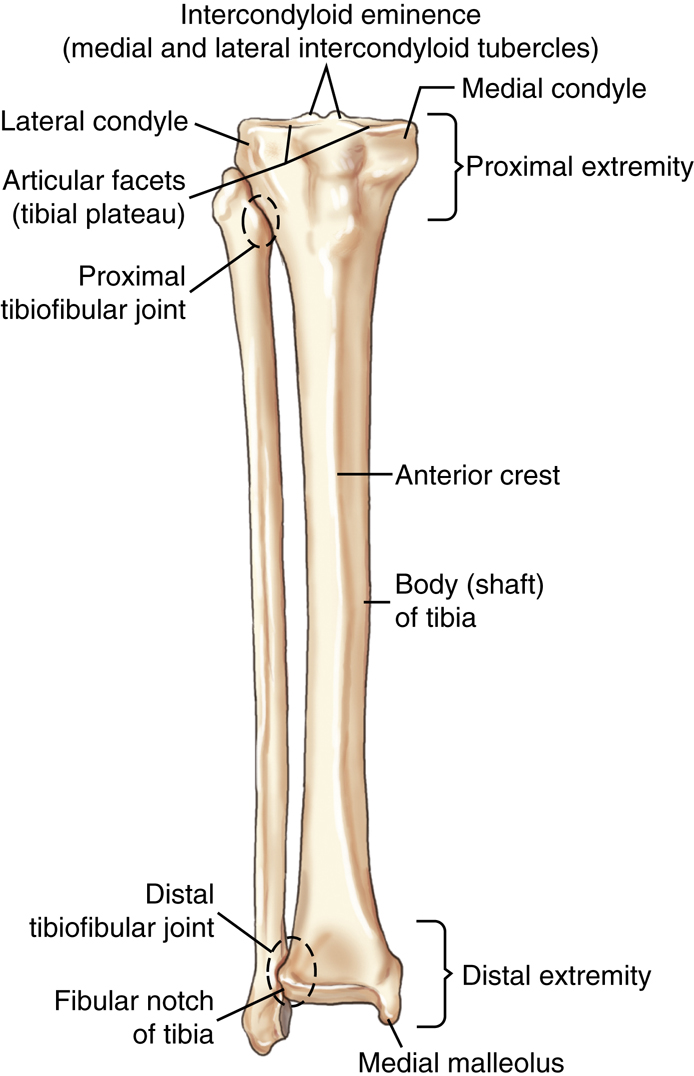

Lower Leg—Tibia and Fibula

The second group of bones of the lower limb to be studied in this chapter consists of the two bones of the lower leg: the tibia and fibula (Fig. 6.17).

Tibia

The tibia, as one of the larger bones of the body, is the weight-bearing bone of the lower leg. The tibia can be felt easily through the skin in the anteromedial part of the lower leg. It is made up of three parts: the central body (shaft) and two extremities.

Proximal Extremity

The medial and lateral condyles are the two large processes that make up the medial and lateral aspects of the proximal tibia.

The intercondylar eminence (also known as the tibial spine) includes two small pointed prominences, called the medial and lateral intercondylar tubercles, which are located on the superior surface of the tibial head between the two condyles.

The upper articular surface of the condyles includes two smooth concave articular facets, commonly called the tibial plateau, which articulate with the femur. As can be seen on the lateral view, the articular facets making up the tibial plateau slope posteriorly from 10° to 20° in relation to the long axis of the tibia

2

(Fig. 6.18). This is an important anatomic consideration because when an AP knee is positioned, the CR must be angled as needed in relation to the image receptor (IR) and the tabletop to be parallel to the tibial plateau. This CR angle is essential in demonstrating an “open” joint space on an AP knee projection.

The tibial tuberosity on the proximal extremity of the tibia is a rough-textured prominence located on the midanterior surface of the tibia just distal to the condyles. This tuberosity is the distal attachment of the patellar tendon, which connects to the large muscle of the anterior thigh. Sometimes in young persons the tibial tuberosity separates from the body of the tibia, a condition known as Osgood-Schlatter disease (see Clinical Indications, p. 226).

Body

The body (shaft) is the long portion of the tibia between the two extremities. Along the anterior surface of the body, extending from the tibial tuberosity to the medial malleolus, is a sharp ridge called the anterior crest or border. This sharp anterior crest is just under the skin surface and often is referred to as the shin or shin bone.

Distal Extremity

The distal extremity of the tibia is smaller than the proximal extremity and ends in a short pyramid-shaped process called the medial malleolus, which is easily palpated on the medial aspect of the ankle.

The lateral aspect of the distal extremity of the tibia forms a flattened, triangular fibular notch for articulation with the distal fibula.

Fibula

The smaller fibula is located laterally and posteriorly to the larger tibia. The fibula articulates with the tibia proximally and the tibia and talus distally. The proximal extremity of the fibula is expanded into a head, which articulates with the lateral aspect of the posteroinferior surface of the lateral condyle of the tibia. The extreme proximal aspect of the head is pointed and is known as the apex of the head of the fibula. The tapered area just below the head is the neck of the fibula.

The body (shaft) is the long, slender portion of the fibula between the two extremities. The enlarged distal end of the fibula can be felt as a distinct “bump” on the lateral aspect of the ankle joint and, as described earlier, is called the lateral malleolus.

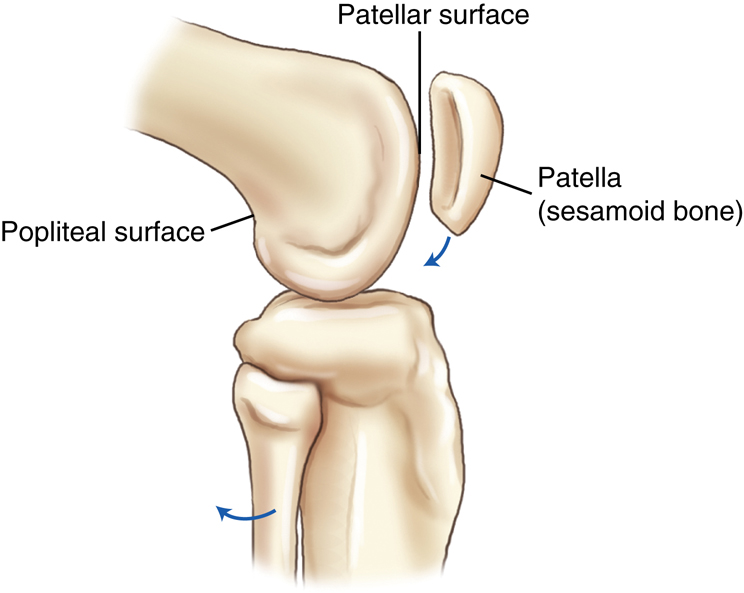

Midfemur and Distal Femur—Anterior View

Similar to all long bones, the body or shaft of the femur is the slender, elongated portion of the bone. The distal femur viewed anteriorly demonstrates the position of the patella or kneecap (Fig. 6.19). The patella, which is the largest sesamoid bone in the body, is located anteriorly to the distal femur. The most distal part of the patella is superior or proximal to the actual knee joint by approximately ½ inch (1.25 cm) in this position with the lower leg fully extended. This relationship becomes important in positioning for the knee joint.

The patellar surface is the smooth, shallow, triangular depression at the distal portion of the anterior femur that extends up under the lower part of the patella, as seen in Fig. 6.19. This depression sometimes is referred to as the intercondylar sulcus. (Sulcus means a groove or depression.) Some literature also refers to this depression as the trochlear groove. (Trochlea means pulley or pulley-shaped structure in reference to the medial and lateral condyles.) All three of these terms should be recognized as referring to this smooth, shallow depression.

The patella itself most often is superior to the patellar surface with the leg fully extended. However, as the leg is flexed, the patella, which is attached to large muscle tendons, moves distally or downward over the patellar surface. This is best shown on the lateral knee drawing (see Fig. 6.21).

Midfemur and Distal Femur—Posterior View

The posterior view of the distal femur best demonstrates the two large, rounded condyles that are separated distally and posteriorly by the deep intercondylar fossa or notch, above which is the popliteal surface (see Fig. 6.20; also Fig. 6.21).

The rounded distal portions of the medial and lateral condyles contain smooth articular surfaces for articulation with the tibia. The medial condyle extends lower or more distally than the lateral condyle when the femoral shaft is vertical, as in Fig. 6.20. This explains why the CR must be angled 5° to 7° cephalad for a lateral knee to cause the two condyles to be directly superimposed when the femur is parallel to the IR. The explanation for this is apparent in Fig. 6.19, which demonstrates that in an erect anatomic position, wherein the distal femoral condyles are parallel to the floor at the knee joint, the femoral shaft is at an angle of approximately 10° from vertical for an average adult. The range is 5° to 15°.

3

This angle would be greater on a person of short stature and a wider pelvis. The angle would be less on a person of tall stature with a narrow pelvis. In general, this angle is greater on a woman than on a man.

A distinguishing difference between the medial and lateral condyles is the presence of the adductor tubercle, a slightly raised area that receives the tendon of an adductor muscle. This tubercle is present on the posterolateral aspect of the medial condyle. It is best seen on a slightly rotated lateral view of the distal femur and knee. The presence of this adductor tubercle on the medial condyle is important in critiquing a lateral knee for rotation. It allows the viewer to determine whether the knee is under-rotated or over-rotated to correct a positioning error when the knee is not in a true lateral position (see the radiograph in Fig. 6.33).

The medial and lateral epicondyles, which can be palpated, are rough prominences for attachments of the medial and lateral collateral ligaments and are located on the outermost portions of the condyles. The medial epicondyle, along with the adductor tubercle, is the more prominent of the two.

Distal Femur and Patella (Lateral View)

The lateral view in Fig. 6.21 shows the relationship of the patella to the patellar surface of the distal femur. The patella, as a large sesamoid bone, is embedded in the tendon of the large quadriceps femoris muscle. As the lower leg is flexed, the patella moves downward and is drawn inward into the intercondylar groove or sulcus. A partial flexion of almost 45°, as shown in Fig. 6.21, demonstrates the patella being pulled only partially downward. With 90° flexion, the patella would move down farther over the distal portion of the femur. This movement and the relationship of the patella to the distal femur become important in positioning for the knee joint and for the tangential projection of the patellofemoral (femoropatellar) joint (articulation between patella and distal femur).

The posterior surface of the distal femur just proximal to the intercondylar fossa is called the popliteal surface, over which popliteal blood vessels and nerves pass.

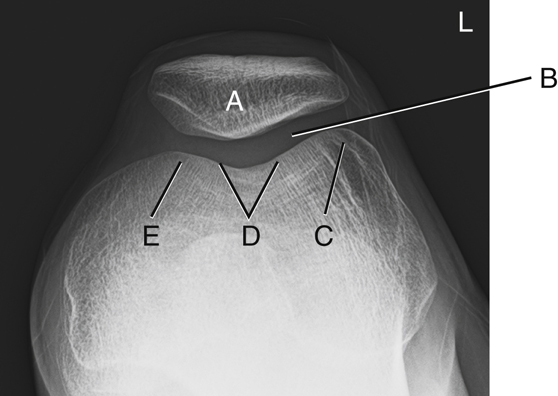

Distal Femur and Patella (Axial View)

The axial or end-on view of the distal femur demonstrates the relationship of the patella to the patellar surface (intercondylar sulcus or trochlear groove) of the distal femur. The patellofemoral joint space is visualized in this axial view (Fig. 6.22). Other parts of the distal femur are also well visualized.

The intercondylar fossa (notch) is shown to be very deep on the posterior aspect of the femur. The epicondyles are seen as rough prominences on the outermost tips of the large medial and lateral condyles.

Patella

The patella (kneecap) is a flat triangular bone approximately 2 inches (5 cm) in diameter (Fig. 6.23). The patella appears to be upside down because its pointed apex is located along the inferior border, and its base is the superior or upper border. The outer or anterior surface is convex and rough, and the inner or posterior surface is smooth and oval shaped for articulation with the femur. The patella serves to protect the anterior aspect of the knee joint and acts as a pivot to increase the leverage of the large quadriceps femoris muscle, the tendon of which attaches to the tibial tuberosity of the lower leg. The patella is loose and movable in its more superior position when the leg is extended and the quadriceps muscles are relaxed. However, as the leg is flexed and the muscles tighten, it moves distally and becomes locked into position. The patella articulates only with the femur, not with the tibia.

Knee Joint

The knee joint proper is a large complex joint that primarily involves the femorotibial joint between the two condyles of the femur and the corresponding condyles of the tibia. The patellofemoral joint is also part of the knee joint, wherein the patella articulates with the anterior surface of the distal femur.

Proximal Tibiofibular Joint and Major Knee Ligaments

The proximal fibula is not part of the knee joint because it does not articulate with any aspect of the femur, even though the fibular (lateral) collateral ligament (LCL) extends from the femur to the lateral proximal fibula, as shown in Fig. 6.24. However, the head of the fibula does articulate with the lateral condyle of the tibia, to which it is attached by this ligament.

Additional major knee ligaments shown on this posterior view are the tibial (medial) collateral ligament (MCL), located medially, and the major posterior and anterior cruciate (kroo′-she-at) ligaments (PCL and ACL), located within the knee joint capsule (Fig. 6.25). (The abbreviations ACL, PCL, LCL, and MCL are commonly used to refer to these four ligaments.

2

) The knee joint is highly dependent on these two important pairs of major ligaments for stability.

The two collateral ligaments are strong bands at the sides of the knee that prevent adduction and abduction movements at the knee. The two cruciate ligaments are strong, rounded cords that cross each other as they attach to the respective anterior and posterior aspects of the intercondylar eminence of the tibia. They stabilize the knee joint by preventing anterior or posterior movement within the knee joint.

In addition to these two major pairs of ligaments, an anteriorly located patellar ligament and various minor ligaments help to maintain the integrity of the knee joint (Fig. 6.26). The patellar ligament is shown as part of the tendon of insertion of the large quadriceps femoris muscle, extending over the patella to the tibial tuberosity. The infrapatellar fat pad, posterior to this ligament, aids in protecting the anterior aspect of the knee joint.

Synovial Membrane and Cavity

The articular cavity of the knee joint is the largest joint space of the human body. The total knee joint is a synovial type enclosed in an articular capsule, or bursa. It is a complex, saclike structure filled with a lubricating-type synovial fluid. This is demonstrated in the arthrogram radiograph, wherein a combination of negative and positive contrast media has been injected into the articular capsule or bursa (Fig. 6.27).

The articular cavity or bursa of the knee joint extends upward under and superior to the patella, identified as the suprapatellar bursa (see Fig. 6.26). Distal to the patella, the infrapatellar bursa is separated by a large infrapatellar fat pad, which can be identified on radiographs. The spaces posterior and distal to the femur also can be seen and are filled with negative contrast media on the lateral arthrogram radiograph.

Menisci (Articular Disks)

The medial and lateral menisci (me-nis′-ci) are crescent-shaped fibrocartilage disks between the articular facets of the tibia (tibial plateau) and the femoral condyles (Fig. 6.28). They are thicker at their external margins, tapering to a very thin center portion. They act as shock absorbers to reduce some of the direct impact and stress that occur at the knee joint. The synovial membrane and the menisci produce synovial fluid, which lubricates the articulating ends of the femur and tibia that are covered with a tough, slick hyaline membrane.

Knee Trauma

The knee has great potential for traumatic injury, especially in activities such as skiing or snowboarding or in contact sports such as football or basketball. A tear of the tibial MCL frequently is associated with a tear of the ACL and a tear of the medial meniscus. Patients with these injuries typically come to the imaging department for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to visualize these soft tissue structures or for knee arthrography.

Review Exercise with Radiographs

Common projections of the lower leg, knee, and patella are shown with labels for an anatomy review.

AP Lower Leg (Fig. 6.29)

Lateral Lower Leg (Fig. 6.30)

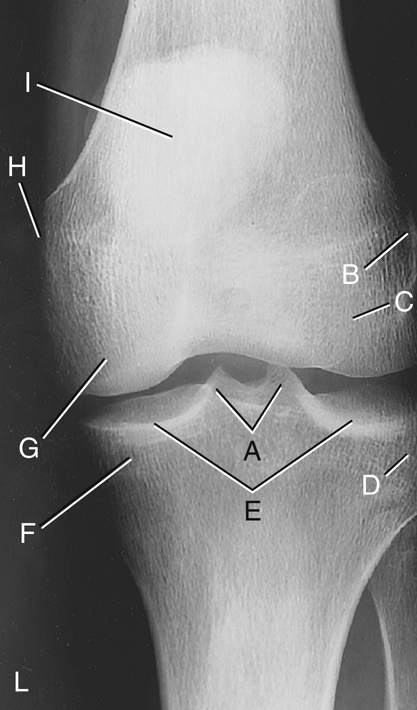

AP Knee (Fig. 6.31)

- A. Medial and lateral intercondylar tubercles; extensions of intercondylar eminence (tibial spine)

- B. Lateral epicondyle of femur

- C. Lateral condyle of femur

- D. Lateral condyle of tibia

- E. Articular facets of tibia (tibial plateau)

- F. Medial condyle of tibia

- G. Medial condyle of femur

- H. Medial epicondyle of femur

- I. Patella (seen through femur)

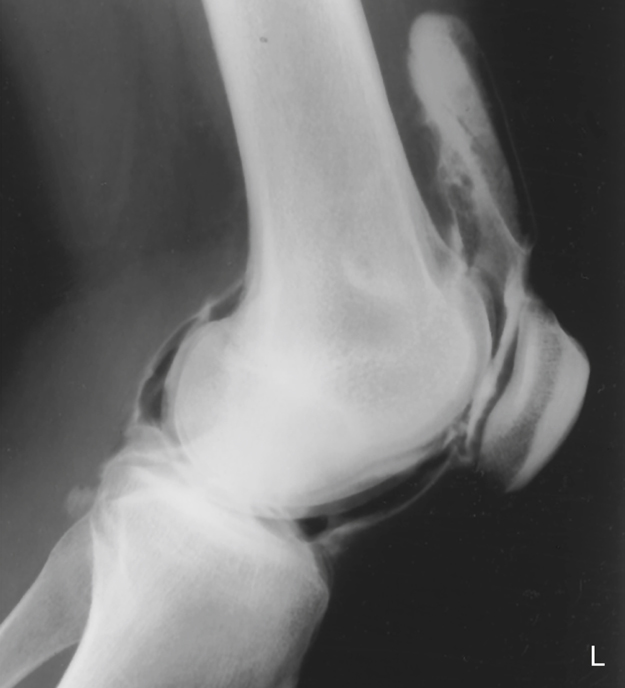

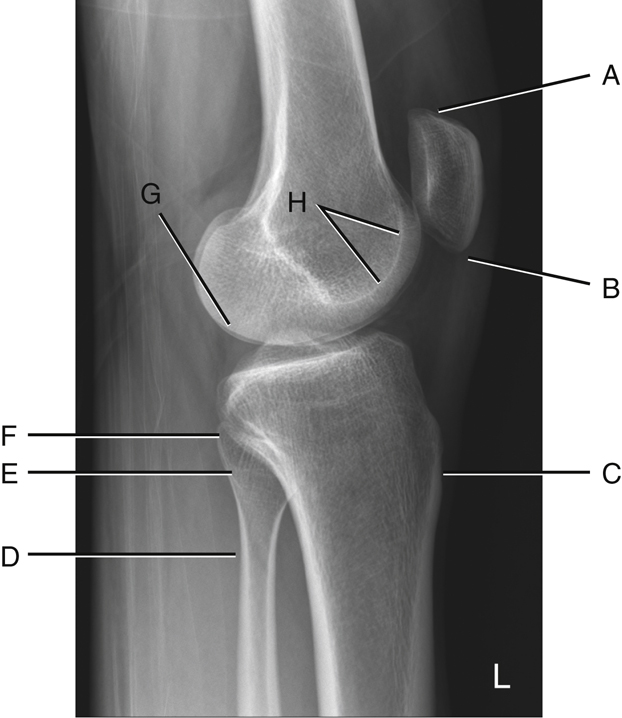

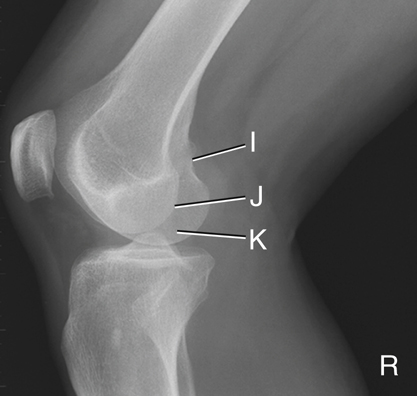

Lateral Knee (Fig. 6.32)

Rotated Lateral Knee (Fig. 6.33)

Projection demonstrates some rotation.

Tangential Projection (Patellofemoral Joint) (Fig. 6.34)

Classification of Joints

The joints or articulations of the lower limb (Fig. 6.35) all (with one exception) are classified as synovial joints and are characterized by a fibrous-type capsule that contains synovial fluid. They also are (with one exception) diarthrodial, or freely movable.

The single exception to the synovial joint is the distal tibiofibular joint, which is classified as a fibrous joint with fibrous interconnections between the surfaces of the tibia and fibula. It is of the syndesmosis type and is only slightly movable, or amphiarthrodial. However, the most distal part of this joint is smooth and is lined with a synovial membrane that is continuous with the ankle joint.

Box 6.2 summarizes the foot, ankle, lower leg, and knee joints.

Surfaces and Projections of the Foot

Surfaces

The surfaces of the foot are sometimes confusing because the top or anterior surface of the foot is called the dorsum. Dorsal usually refers to the posterior part of the body. Dorsum, in this case, comes from the term dorsum pedis, which refers to the upper surface, or the surface opposite the sole of the foot.

The sole of the foot is the posterior surface or plantar surface. These terms are used to describe common projections of the foot.

Projections

The AP projection of the foot is the same as a dorsoplantar (DP) projection. The less common posteroanterior (PA) projection can also be called a plantodorsal (PD) projection (Fig. 6.36). Technologists should be familiar with each of these projection terms and should know which projection they represent.

Motions of the Foot and Ankle

Other potentially confusing terms involving the ankle and intertarsal joints are dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, inversion, and eversion (Fig. 6.37). To decrease the angle (flex) between the dorsum pedis and the anterior part of the lower leg is to dorsiflex at the ankle joint. Extending the ankle joint or pointing the foot and toe downward with respect to the normal position is called plantar flexion.