4: Data acquisition concepts

Learning objectives

On completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- 1. identify the basic components of a typical data acquisition scheme used in CT scanning.

- 2. explain each of the following:

- • scanning

- • ray

- • view

- • projection profile

- • data sample.

- 3. describe the essential characteristics of five generations of CT data acquisition geometries.

- 4. compare and contrast two types of slip-ring systems for use in CT scanners.

- 5. describe the elements of an x-ray generator used in CT.

- 6. outline the main features of x-ray tubes, filtration, and collimation in CT.

- 7. describe recent design innovations in CT x-ray tubes.

- 8. describe briefly what is meant by each of the following characteristics of CT detectors:

- • efficiency

- • stability

- • response time

- • dynamic range.

- 9. outline the principles of each of the following types of detectors:

- • scintillation detectors

- • gas-ionization detectors

- • photon counting detectors.

- 10. outline the essential design innovations in CT detectors and detector electronics.

- 11. state the purpose of the DAS and explain how it works.

- 12. outline briefly the essential elements of three methods of increasing the number of samples (transmission measurements) needed for image reconstruction in CT.

Basic scheme for data acquisition

In computed tomography (CT), transmission measurements, or projection data, are systematically collected from the patient. Several schemes are available for such data collection, each based on a specific “geometrical pattern of scanning” (Villafana, 1987).

Data acquisition refers to the method by which the patient is scanned to obtain enough data for image reconstruction. Scanning is defined by the beam geometry, which characterizes the particular CT system and also plays a central role in spatial resolution and artifact production.

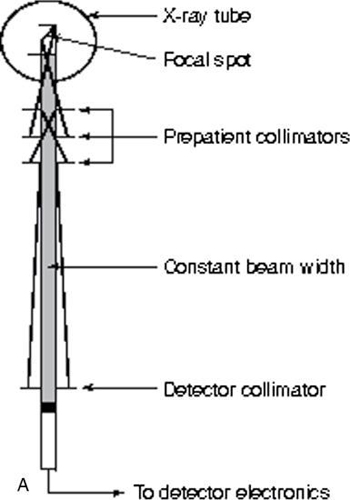

Two elements in a basic scheme for data acquisition (Fig. 4.1) are the beam geometry and the components comprising the scheme. Beam geometry refers to the size, shape, and motion of the beam and its path, and components refer to those physical devices that shape and define the beam, measure its transmission through the patient, and convert this information into digital data for input into the computer.

The following points should be noted from Fig. 4.1:

- 1. The x-ray tube and detector are in perfect alignment.

- 2. The tube and detector scan the patient to collect a large number of transmission measurements.

- 3. The beam is shaped by a special filter as it leaves the tube.

- 4. The beam is collimated to pass through only the slice of interest.

- 5. The beam is attenuated by the patient and the transmitted photons are then measured by the detector.

- 6. The detector converts the x-ray photons into an electrical signal (analog data).

- 7. These signals are converted by the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) into digital data.

- 8. The digital data are sent to the computer for image reconstruction.

Terminology

Consider the first data acquisition scheme used by Hounsfield (1973) and others early in the development of CT (Fig. 4.2). The x-ray tube and detector move across the object or patient in a straight line, or translate, to collect several transmission measurements. After the first translation, the tube and detector rotate by 1 degree to collect more measurements. This sequence is repeated until data are collected for at least 180 degrees for one slice of the anatomy. Scanning also includes the movement of the patient through the gantry to scan the next slice. This sequence is repeated until all slices have been scanned.

The x-ray beam that emanates from the tube consists of several rays. In CT, a ray is the part of the beam that falls on one detector. In Fig. 4.2, the line from the x-ray tube to the detector is considered a single ray, and a collection of these rays for one translation across the object constitutes a view.

Projection data are collected by the detector because each ray is attenuated by the patient and subsequently transmitted and projected on the detector. The detector in turn generates an electrical signal, which represents a signature of the attenuation as the ray moves across the slice. This signal represents a profile. Although a view generates a profile, a ray generates only a small part of the profile. In addition, each transmission measurement is referred to as a data sample.

The production of a CT image of one slice of the anatomy requires a large set of data samples taken at different locations to satisfy the image reconstruction process. The total number of data samples (DStotal) per scan is given by the following expression:

or

Data acquisition geometries

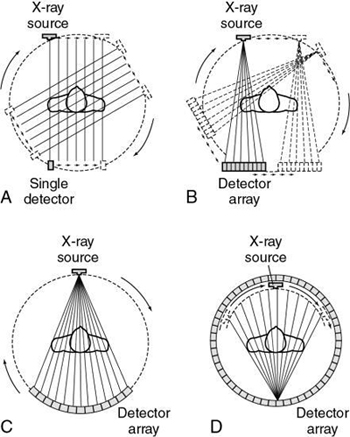

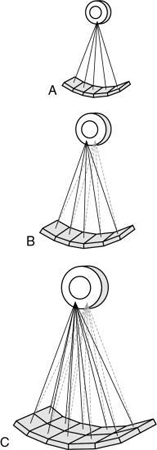

Three primary types of acquisition geometries are parallel beam geometry, fan beam geometry, and CT scanning in spiral or helical geometry, which is the most recently developed geometry. As a result, a simple categorization of CT equipment has evolved based on the scanning geometry, scanning motion, and number of detectors, as follows (Fig. 4.3):

- 1. First-generation scanners were based on the parallel beam geometry and translate-rotate scanning motion.

- 2. Second-generation scanners were based on the fan beam geometry and translate-rotate motion.

- 3. Third-generation scanners were based on fan beam geometry and complete rotation of the tube and detectors.

- 4. Fourth-generation scanners were based on fan beam geometry and complete rotation of the x-ray tube around a stationary ring of detectors.

- 5. Fifth-generation scanners were developed primarily for high-speed CT scanning. These scanners are based on special configurations intended to facilitate very fast scanning.

- 6. Sixth-generation scanners have multiple x-ray tubes and detectors. These scanners are intended specifically to image moving structures, such as the heart. One such recent scanner is the dual-source CT (DSCT) scanner (McCollough et al., 2007).

- 7. Seventh-generation scanners use flat-panel digital area detectors similar to the ones used in digital radiography (Flohr et al., 2005; Kalender, 2005).

First-generation scanners

Parallel beam geometry was first used by Hounsfield (1973). The first EMI brain scanner and other earlier scanners were based on this concept.

Parallel beam geometry is defined by a set of parallel rays that generates a projection profile (see Fig. 4.2). The data acquisition process is based on a translate-rotate principle, in which a single, highly collimated x-ray beam and one or two detectors first translate across the patient to collect transmission readings. After one translation, the tube and detector rotate by 1 degree and translate again to collect readings from a different direction. This is repeated for 180 degrees around the patient. This method of scanning is referred to as rectilinear pencil beam scanning.

First-generation CT scanners took at least 4.5 to 5.5 minutes to produce a complete scan of the patient, which restricted patient throughput. The image reconstruction algorithm for first-generation CT scanners was based on the parallel beam geometry of the image reconstruction space (a square or circle in which the slice to be reconstructed must be positioned).

Second-generation scanners

Second-generation scanners were based on the translate-rotate principle of first-generation scanners with a few fundamental differences, such as a linear detector array (about 30 detectors) coupled to the x-ray tube and multiple pencil beams. The result is a beam geometry that describes a small fan whose apex originates at the x-ray tube. This is the fan beam geometry shown in Fig. 4.3B–D.

Also, the rays are divergent instead of parallel, resulting in a significant change in the image reconstruction algorithm, which must be capable of handling projection data from the fan beam geometry.

In second-generation scanners, the fan beam translates across the patient to collect a set of transmission readings. After one translation, the tube and detector array rotate by larger increments (compared with first-generation scanners) and translate again. This process is repeated for 180 degrees and is referred to as rectilinear multiple pencil beam scanning. The x-ray tube traces a semicircular path during scanning.

The larger rotational increments and increased number of detectors result in shorter scan times that range from 20 seconds to 3.5 minutes. In general, the time decrease is inversely proportional to the number of detectors. The more detectors, the shorter is the total scan time.

Third-generation scanners

Third-generation CT scanners were based on a fan beam geometry that rotates continuously around the patient for 360 degrees (see Fig. 4.3). The x-ray tube is coupled to a curved detector array that subtends an arc of 30 to 40 degrees or greater from the apex of the fan. As the x-ray tube and detectors rotate, projection profiles are collected and a view is obtained for every fixed point of the tube and detector. This motion is referred to as continuously rotating fan beam scanning. The path traced by the tube describes a circle rather than the semicircle characteristic of first- and second-generation CT scanners. Third-generation CT scanners collect data faster than the previous units (generally within a few seconds). This scan time increases patient throughput and limits the production of artifacts caused by respiratory motion.

Fourth-generation scanners

Essentially, fourth-generation CT scanners feature two types of beam geometries: a rotating fan beam within a stationary ring of detectors and a nutating fan beam in which the apex of the fan (x-ray tube) is located outside a nutating ring of detectors.

Rotating fan beam within a circular detector array

The main data acquisition features of a fourth-generation CT scanner are as follows:

- 1. The x-ray tube is positioned within a stationary, circular detector array (Fig. 4.4).

- 2. The beam geometry describes a wide fan.

- 3. The apex of the fan now originates at each detector. Fig. 4.4 shows two fans that describe two sets of views.

- 4. As the tube moves from point to point within the circle, single rays strike a detector. These rays are produced sequentially during the point’s circular travel.

- 5. Scan times are very short and vary from scanner to scanner, depending on the manufacturer.

- 6. The x-ray tube traces a circular path.

- 7. The image reconstruction algorithm is for a fan beam geometry in which the apex of the fan is now at the detector, as opposed to the x-ray tube in the third-generation systems.

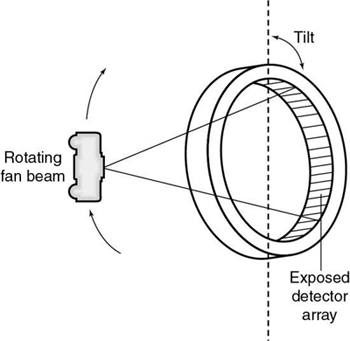

Rotating fan beam outside a nutating detector ring

In this scheme, the x-ray tube rotates outside the detector ring (Fig. 4.5). As it rotates, the detector ring tilts so that the fan beam strikes an array of detectors located at the far side of the x-ray tube while the detectors closest to the x-ray tube move out of the path of the x-ray beam. The term nutating describes the tilting action of the detector ring during data collection. Scanners with this type of scanning motion eliminate the poor geometry of other schemes, in which the tube rotates inside its detector ring, near the object. However, nutate-rotate systems are not currently manufactured.

Multislice CT scanners: CT scanning in spiral-helical geometry

Scanning in spiral-helical geometry is the most recent development in CT data acquisition. The need for faster scan times and improvements in 3D and multiplanar reconstruction have encouraged the development of continuous rotation scanners, or volume scanners, in which the data are collected in volumes rather than individual slices. CT scanning in spiral/helical geometry is based on slip-ring technology, which shortens the high-tension cables to the x-ray tube to allow continuous rotation of the gantry. The path traced by the x-ray tube, or fan beam, during the scanning process describes a spiral (Fig. 4.6) or a helix. The terms spiral geometry (Siemens) and helical geometry (Toshiba) are commonly and synonymously used to describe the data acquisition geometry of continuous rotation scanners (see Appendix A). This geometry is obtained during the scanning process. As the tube rotates, the patient is transported through the gantry aperture for a single breath-hold. Because this results in a volume of the patient being scanned, the term volume CT is also used.

Spiral/helical geometry scanners

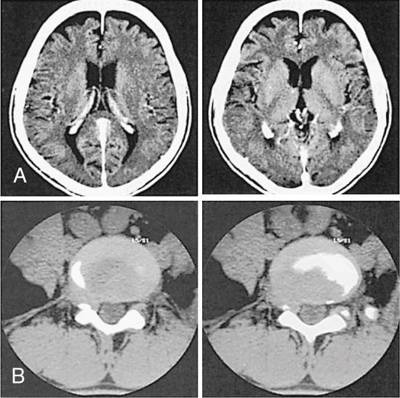

These systems have evolved through the years from two to eight slices per revolution of the x-ray tube and detectors (360-degree rotation) to 16, 32, 40, 64, and 320 slices per 360-degree rotation. In 2007, a prototype scanner featuring 256 slices per 360-degree rotation was developed by Toshiba Medical Systems (Japan) for imaging moving structures such as the heart and lungs. One striking feature of this scanner compared with other multislice scanners is that it covers the entire heart in a single rotation (Fig. 4.7). The lessons learned from this scanner subsequently led to the 320-CT scanner popularly known as the Aquilion family of CT scanners (examples include the Aquilion ONE and the Aquilion PRIME family of scanners [40, 80, 160, 320, and 640 slices per revolution] commercially available from Canon Medical Systems formerly Toshiba Medical Systems).

An interesting point with respect to scanners capable of imaging 16 or greater slices per 360-degree rotation is that the beam becomes a cone. These systems are therefore based on cone-beam geometries (as opposed to fan beam geometries) because the detectors are 2D detectors. This means that cone-beam algorithms (as opposed to fan beam algorithms) are used to reconstruct images. Multislice CT (MSCT) scanner principles and concepts are described in detail in Chapter 12.

Fifth-generation scanners

Fifth-generation scanners are classified as high-speed CT scanners because they can acquire scan data in milliseconds. Two such scanners are the electron-beam CT scanner (EBCT; Fig. 4.8) and the dynamic spatial reconstructor (DSR) scanner. In the EBCT scanner, the data acquisition geometry is a fan beam of x rays produced by a beam of electrons that scans several stationary tungsten target rings. The fan beam passes through the patient, and the x-ray transmission readings are collected for image reconstruction. The DSR scanner was labeled a high-speed CT scanner capable of producing dynamic 3D images of volumes of the patient. The DSR is now obsolete and is not described further in this book.

The principles and operation of the EBCT scanner were first described by Boyd et al. (1979) as a result of research done at the University of California at San Francisco during the late 1970s. In 1983, Imatron developed Boyd’s high-speed CT scanner for imaging the heart and circulation (Boyd & Lipton, 1983). At that time, the machine was referred to by such names as the cardiovascular computed tomography scanner and the cine CT scanner. Today, the machine is known as the EBCT scanner (McCollough, 1995). It is expected that more of these machines will be distributed worldwide in the near future. (Siemens Medical Systems will distribute the EBCT scanner under the name “Evolution.”)

The overall goal of the EBCT scanner is to produce high-resolution images of moving organs (e.g., the heart) that are free of artifacts caused by motion. In this respect, the scanner can be used for imaging the heart and other body parts in both adults and children. The scanner performs this task well because its design enables it to acquire CT data 10 times faster than conventional CT scanners.

The design configuration of the EBCT scanner (see Fig. 4.8) is different from that of conventional CT systems in the following respects:

The basic configuration of an EBCT scanner is shown in Fig. 4.8. At one end of the scanner is an electron gun that generates a 130-kilovolt (kV) electron beam. This beam is accelerated, focused, and deflected at a prescribed angle by electromagnetic coils to strike one of the four adjacent tungsten target rings. These stationary rings span an arc of 210 degrees. The electron beam is steered along the rings, which can be used individually or in any sequence. As a result, heat dissipation does not pose a problem as it does in conventional CT systems.

When the electron beam collides with the tungsten target, x rays are produced. Collimators shape the x rays into a fan beam that passes through the patient, who is positioned in a 47-cm scan field, to strike a curved, stationary array of detectors positioned opposite the target rings.

The detector array consists of two separate rings holding a 216-degree arc of detectors. The first ring holds 864 detectors, each half the size of those in the second ring, which holds 432 detectors (McCollough, 1995). This arrangement allows for the acquisition of either two image slices when one target ring is used or eight image slices when all four target rings are used in sequence.

Each solid-state detector consists of a luminescent crystal and cadmium tungstate (which converts x rays to light) coupled optically with silicon photodiodes (which convert light into current) connected to a preamplifier. The output from the detectors is sent to the data acquisition system (DAS; see Fig. 4.8).

The DAS consists of ADCs, or digitizers, that sample and digitize the output signals from the detectors. In addition, the digitized data are stored in bulk in random access memory, which can hold data for hundreds of scans in the multislice and single-slice modes. This information is subsequently sent to the computer for processing.

The computer for the EBCT scanner is capable of very fast reconstruction speeds, and image reconstruction is based on the filtered back-projection algorithm used in conventional CT systems.

The EBCT scanner does not have any moving physical parts and, as noted by Flohr et al. (2005), “the EBCT principle is currently not considered adequate for state-of-the-art cardiac imaging or for general radiology applications.”

Sixth-generation scanners: The dual-source CT scanner

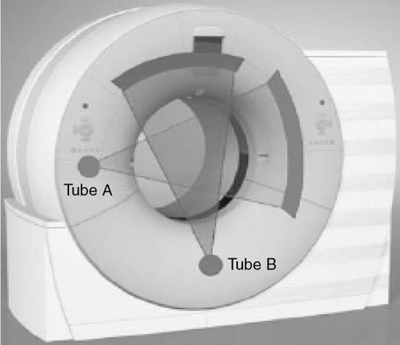

The overall goal of the MSCT scanners mentioned previously is to improve the volume coverage speed while providing improved spatial and temporal resolution compared with the older four slices per 360-degree rotation scanner. Although the current 64-slice volume scanners produce better spatial resolution in the order of 0.4 mm isotropic voxels (Flohr et al., 2006; McCollough et al., 2007) and temporal resolution compared with the 16-slice volume CT scanner, they fail to deal effectively with artifacts created in CT angiography (CTA) and the problem of the mechanical forces that need to be addressed in attempting to decrease the rotation time of the x-ray tube and detectors (Flohr et al., 2006). To solve these problems, for example, a new-generation scanner has been introduced. This is the DSCT scanner.

This scanner consists of two x-ray tubes and two sets of detectors that are offset by 90 degrees (Fig. 4.9). The DSCT scanner is designed for cardiac CT imaging because it provides the temporal resolution needed to image moving structures such as the heart. The DSCT scanner will be described further in Chapter 13.

Seventh-generation scanners: Flat-panel CT scanners

Flat-panel digital detectors similar to the ones used in digital radiography are now being considered for use in CT; however, these scanners are still in the prototype development and are not available for use in clinical imaging. Perhaps they may be labeled seventh-generation CT scanners on the basis of the simple categorization mentioned above.

A flat-panel CT scanner prototype is shown in Fig. 4.10. The x-ray tube and detectors are coupled and positioned in the CT gantry. The detector consists of a cesium iodide (CsI) scintillator coupled to an amorphous, silicon thin-film transistor array. These flat-panel detectors produce excellent spatial resolution but lack good contrast resolution; therefore, they are also used in angiography to image blood vessels, for example, where the image sharpness is of primary importance. As noted by Flohr et al. (2005),

the combination of area detectors that provide sufficient image quality with fast gantry rotation speed will be a promising technical concept for medical CT systems. The vast spectrum of potential applications may bring about another quantum leap in the evolution of medical CT imaging.

In addition, flat-panel detectors are also being investigated for use in CT of the breast, and currently several dedicated breast CT prototypes are being developed (Glick et al., 2007; Kwan et al., 2007). Breast CT is described further in Chapter 13.

Slip-ring technology

Spiral-helical CT is made possible through the use of slip-ring technology, which allows for continuous gantry rotation. Slip rings (Fig. 4.11) are “electromechanical devices consisting of circular electrical conductive rings and brushes that transmit electrical energy across a rotating interface” (Brunnett, 1990). Today, CT scanners incorporate slip-ring design and are referred to as continuous rotation, volume CT, or slip-ring scanners. Slip-ring technology is not a new idea and has been applied previously in CT. For example, the Varian V-360-3 CT scanner (an old model CT scanner) was based on slip-ring design to achieve continuous rotation of the gantry. Such rotation results in very fast data collection, which is mandatory for certain clinical procedures such as dynamic CT scanning and CTA.

In addition, slip rings not only provide the electrical power to operate the x-ray tube but also transfer the signals from the detectors for input into the image reconstruction computer.

Design and power supply

Two slip-ring designs are the disk (Fig 4.12A) or pancake type (Fig. 4.12B) and cylinder. In the disk design, the conductive rings form concentric circles in the plane of rotation. The cylindrical design includes conductive rings positioned along the axis of rotation to form a cylinder (Fig. 4.13A). The brushes that transmit electrical power to the CT components glide in contact grooves on the stationary slip ring (see Fig. 4.13A).

Two common brush designs are the wire brush and the composite brush. The wire brush uses conductive wire as a sliding contact. “A brush consists of one or more wires arranged such that they function as a cantilever spring with a free end against the conductive ring. Two brushes per ring are often used to increase either communication reliability or current carrying capacity” (Brunnett, 1990). The composite brush uses a block of some conductive material (e.g., a silver-graphite alloy) as a sliding contact. A variety of different spring designs are commonly used to maintain contact between the brush and ring including cantilever, compression, or constant force. Examples of brush blocks are shown in Fig. 4-13B,C.

The most recent advance in the design of slip rings is the contactless slip ring as shown in Fig. 4.14. This design makes it possible to transfer electrical energy across a rotating interface without the use of electrical contacts.

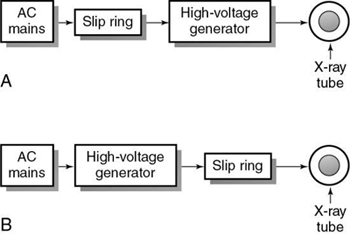

Slip-ring scanners provide continuous rotation of the gantry through the elimination of the long high-tension cables to the x-ray tube used in conventional start–stop scanners, which must be unwound after a complete rotation. In conventional scanners, these cables originate from the high-voltage generator, usually located in the x-ray room. The high-voltage generators of slip-ring scanners are located in the gantry. Scanners with either low-voltage or high-voltage slip rings, based on the power supply to the slip ring, are available (Fig. 4.15).

Low-voltage slip ring

In a low-voltage slip-ring system, 480 alternating (AC) power and x-ray control signals are transmitted to slip rings by means of low-voltage brushes that glide in contact grooves on the stationary slip ring. The slip ring then provides power to the high-voltage transformer, which subsequently transmits high voltage to the x-ray tube (see Fig. 4.15A). In this case, the x-ray generator, x-ray tube, and other controls are positioned on the orbital scan frame.

High-voltage slip ring

In a high-voltage slip-ring system (see Fig. 4.15B), the AC delivers power to the high-voltage generator, which subsequently supplies high voltage to the slip ring. The high voltage from the slip ring is transferred to the x-ray tube. In this case, the high-voltage generator does not rotate with the x-ray tube.

Advantages

The major advantage of slip-ring technology is that it facilitates continuous rotation of the x-ray tube so that volume data can be acquired quickly from the patient. As the tube rotates continuously, the patient is translated continuously through the gantry aperture. This results in CT scanning in spiral geometry. Other advantages are as follows:

X-ray system

In his initial experiments, Hounsfield (1973) used low-energy, monochromatic gamma-ray radiation. He later conducted experiments with an x-ray tube because of several limitations imposed by the monochromatic radiation source, such as the low radiation intensity rate, large source size, low source strength, and high cost. Subsequently, CT scanners were manufactured to function with x-ray tubes to provide the high radiation intensities necessary for clinical high-contrast CT scanning. However, the heterogeneous beam was problematic because it did not obey the Lambert–Beer exponential law (see Equation 3.1).

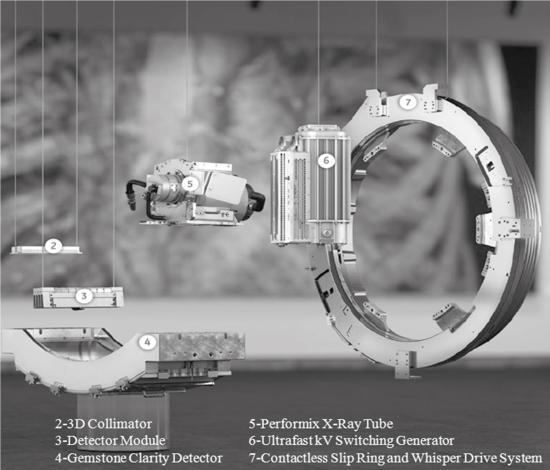

The components of the x-ray system include the x-ray generator, x-ray tube, x-ray beam filter, and collimators (see Figs. 4.1 and 4.14).

X-ray generator

CT scanners use three-phase power for the efficient production of x rays. In the past, generators for CT scanners were based on the 60-Hertz (Hz) voltage frequency, so the high-voltage generator was a bulky piece of equipment located in a corner of the x-ray room. A long high-tension cable ran from the generator to the x-ray tube in the gantry.

CT scanners now use high-frequency generators, which are small, compact, and more efficient than conventional generators. These generators are located inside the CT gantry. In some scanners, the high-frequency generator is mounted on the rotating frame with the x-ray tube; in others it is located in a corner of the gantry and does not rotate with the tube.

In a high-frequency generator (Fig. 4.16), the circuit is usually referred to as a high-frequency inverter circuit. The low-voltage, low-frequency current (60 Hz) from the main power supply is converted to high-voltage, high-frequency current (500 to 25,000 Hz) as it passes through the components, as shown in Figure 4-16. Each component changes the low-voltage, low-frequency AC waveform to supply the x-ray tube with high-voltage, high-frequency direct current of almost constant potential. After high-voltage rectification and smoothing, the voltage ripple from a high-frequency generator is less than 1%, compared with 4% from a three-phase, 12-pulse generator. This makes the high-frequency generator more efficient at x-ray production than its predecessor. The x-ray exposure technique obtained from these generators depends on the generator power output. The power ratings of CT generators vary and depend on the CT vendor; however, typical ratings can range from 20 to 100 kilowatts (kW; Kalender, 2005). More recently CT manufacturers have generators capable of 120 kW. The interested student should refer to CT manufacturers’ website descriptions for up-to-date specifications on CT x-ray generators. An output capacity of, say, 60 kW will provide a range of kilovolt and milliampere settings, where 80 and 120 to 140 kV and 20 to 500 milliamperes (mA) with 1-mA increments are typical.

X-ray tubes

The radiation source requirement in CT depends on two factors: (1) radiation attenuation, which is a function of radiation beam energy, the atomic number and density of the absorber, and the thickness of the object and (2) the quantity of radiation required for transmission. X-ray tubes satisfy this requirement.

First- and second-generation scanners used fixed-anode, oil-cooled x-ray tubes, but rotating anode x-ray tubes have become common in CT because of the demand for increased output. These rotating anode tubes, an example of which is shown in Fig. 4.17, produce a heterogeneous beam of radiation from a large-diameter anode disk with focal spot sizes to facilitate the spatial resolution requirements of the scanner. The disk is usually made of a rhenium, tungsten, and molybdenum (RTM) alloy and other materials with a small target angle (usually 12 degrees) and a rotation speed of 3600 revolutions per minute (rpm) to 10,000 rpm (high-speed rotation). Fig. 4.17B shows an upgraded tube based on the technology used in the tube shown in Figure 4.17A.

The introduction of spiral/helical CT with continuous rotation scanners has placed new demands on x-ray tubes. Because the tube rotates continually for a longer period compared with conventional scanners, the tube must be able to sustain higher power levels. Several technical advances in component design have been made to achieve these power levels and deal with the problems of heat generation, heat storage, and heat dissipation. For example, the tube envelope, cathode assembly, anode assembly including anode rotation, and target design have been redesigned (Fox, 1995; Homberg & Koppel, 1997).

The glass envelope ensures a vacuum, provides structural support of anode and cathode structures, and provides high-voltage insulation between the anode and cathode. Internal getters (ion pumps) remove air molecules to ensure a vacuum. Although the borosilicate glass provides good thermal and electrical insulation, electrical arcing results from tungsten deposits on the glass caused by vaporization. Tubes with metal envelopes, which are now common, solve this problem. Ceramic insulators (see Fig. 4.17A) isolate the metal envelope from the anode and cathode voltage. Metal envelope tubes have larger anode disks; for example, the tube shown in Fig. 4.17 has a disk with a 200-mm diameter compared with the 120- to 160-mm diameter typical of conventional tubes. This feature allows the technologist to use higher tube currents. Heat-storage capacity is also increased with an improvement in heat dissipation rates.

The cathode assembly consists of one or more tungsten filaments positioned in a focusing cup. The getter is usually made of barium to ensure a vacuum by the absorption of air molecules released from the target during operation.

The anode assembly consists of the disk, rotor stud and hub, rotor, and bearing assembly. The large anode disk is thicker than conventional disks; the three basic designs are the conventional all-metal disk (Fig. 4.18), the brazed graphite disk, and the chemical vapor deposition (CVD) graphite disk. In conventional tubes, the all-metal disk (see Fig. 4.18A) consists of a base body made of titanium, zirconium, and molybdenum with a focal track layer of 10% rhenium and 90% tungsten. It can transfer heat from the focal track very quickly. Unfortunately, tubes with this all-metal design cannot meet the needs of spiral/helical CT imaging because of their weight.

The brazed graphite anode disk (see Fig. 4.18B) consists of a tungsten-rhenium focal track brazed to a graphite base body. Graphite increases the heat-storage capacity because of its high thermal capacity, which is about 10 times that of tungsten. As noted by Fox (1995), the material used in the brazing process influences the operating temperature of the tube, and the higher temperatures result in higher heat-storage capacities and faster cooling of the anode. Tubes for spiral/helical CT scanning are based mostly on this type of design.

The final type of anode design (see Fig. 4.18C) is also intended for use in spiral/helical CT x-ray tubes. The disk consists of a graphite base body with a tungsten-rhenium layer deposited on the focal track by a chemical vapor process. This design can accommodate large, lightweight disks with large heat-storage capacity and fast cooling rates (Fox, 1995).

The purpose of the bearing assembly is to provide and ensure smooth rotation of the anode disk. In CT, high-speed anode rotation allows the use of higher loadability. Rotation speeds of 10,000 rpm are possible with increased frequency to the stator windings. Smooth rotation of the disk is possible because of the ball bearings lubricated with silver; however, because ball-bearing technology results in mechanical problems and limits x-ray tube performance, a liquid-bearing method to improve anode disk rotation was introduced (Fig. 4.19).

The stationary shaft of the anode assembly consists of grooves that contain gallium-based liquid metal alloy. During anode rotation, the liquid is forced into the grooves and results in a hydroplaning effect between the anode sleeve and liquid (Homberg & Koppel, 1997). The purpose of this bearing technology is to conduct heat away from the x-ray tube more efficiently than conventional ball bearings with improved tube cooling. Additionally, the liquid-bearing technology is free of vibrations and noise.

As noted by Fox (1995), the rotor hub and rotor stud also prevent the transmission of heat from the disk to the bearings. The rotor is a copper cylinder “brazed to an inner steel cylinder with a ceramic coating around the outside to enhance heat radiation” (Fox, 1995).

The working life of the tubes can range from about 10,000 to 40,000 hours, compared with 1000 hours, which is typical of conventional tubes with conventional bearing technology.

Straton x-ray tube: A new x-ray tube for MSCT scanning

As noted previously, the fundamental problem with conventional x-ray tubes is that of heat dissipation and slow cooling rates. Efforts have been made to deal with these problems by introducing various designs, such as large anode disks and the introduction of the compound anode design (RTM disk), which has higher heat-storage capacities and cooling rates. Additionally, as gantry rotation times increase, higher milliampere values are needed to provide the same milliamperes per rotation. As the electrical load (milliamperes and kilovolts) increases, faster anode cooling rates are needed. Despite these efforts, the problems of heat transfer and slow cooling rates still persist with MSCT scanners, especially for multiple longer scan times and cardiac CT imaging.

To overcome these problems, a new type of x-ray tube has been introduced for use with MSCT scanners. This unique and revolutionary tube was designed by Siemens Medical Solutions (Siemens AG Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). Because this tube represents a new technology for dealing with the problem of x-ray tube heat in MSCT scanning and leads to an innovative method of improving image quality in CT, it is described here.

A photograph of the Straton x-ray tube is shown in Fig. 4.20. As can be seen, it is encased in a protective housing that contains oil for cooling. The tube is compact in design and is much smaller than conventional x-ray tubes described earlier. This size ensures a fast gantry rotation of 0.37 seconds (Kalender, 2005).

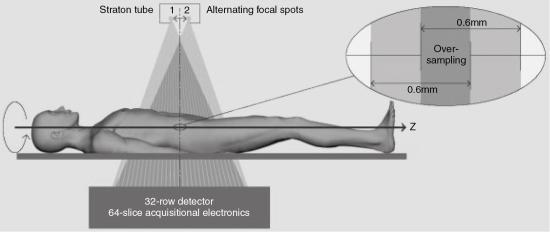

The Straton x-ray tube, illustrated in Fig. 4.21, has anode and cathode structures, deflection coils, an electron beam, and a motor. The electron beam produced by the filament housed in the cathode assembly is deflected to strike the anode (120-mm diameter) to produce x rays used for imaging. The motor provides the rotation of the entire tube, which is immersed in oil. It is important to note that the anode is in direct contact with the oil (directly cooled tube), which is forced out of the housing for cooling and subsequently circulates back into the housing. Because the anode is in direct contact with the circulating oil, very high cooling rates of 5.0 mega heat unit (MHU)/min result in about 0 MHU anode heat-storage capacity. The advantage of this is that high-speed volume scanning is possible with high milliamperes and long exposure times for increasing length of anatomic coverage. A comparison of the design structures of both conventional and the Straton x-ray tubes is illustrated in Fig. 4.22. Another important feature of the Straton x-ray tube relates to the electron beam from the cathode. This beam is deflected to strike the anode at two precisely located focal spots (Fig. 4.23) that vary in size. Kalender (2005) reported that the sizes can be 0.6 mm × 0.17 mm, 0.8 mm × 1.1 mm, and 0.7 mm × 0.7 mm. The electron beam alternates at about 4640 times per second to create two separate x-ray beams that pass through the patient and fall on the detectors. This is described later in the chapter.

Alternative x-ray tube designs for multislice CT

Two alternative designs in x-ray tube technology for use in MSCT are shown in Fig. 4.24, one from Philips Healthcare (2005; Fig 4-24A) and the other from Siemens Healthcare (Fig 4-24B). Both of these x-ray tubes are directly cooled x-ray tubes (direct anode cooling).

The Philips Healthcare x-ray tube is an upgraded Maximus Rotalix Ceramic (iMRC) x-ray tube technology (second-generation technology) based on metal/ceramic technology and a noiseless wear-free spiral groove bearing with a large area liquid metal contact and a 200-mm graphite-backed, dual-suspended hydrodynamic bearing with a segmented all-metal (Shefer et al., 2013) anode disk, which facilitates very high heat loading capacity and rapid heat dissipation. The upgraded tube also features what has been referred to as the dynamic focal spot (DFS), which increases the data sampling and generates artifact-free ultra-high spatial resolution. The updated technical data for the iMRC 800 x-ray tube are listed in Table 4.1.

| Features | Values |

|---|---|

| Maximum tube power | 60 kW |

| Nominal anode input power (IEC 60613) | 85 kW (small) and 120 kW (large) |

| Effective heat-storage capacity | 26 MHUeff |

| Anode heat-storage capacity (IEC 60613) | 8 MHU |

| Maximum heat content of assembly | 12 MHU |

| Maximum continuous heat dissipation | 6.1 kW |

| Anode disk diameter | 200 mm |

| Anode angle | 7 degrees |

| Focal spot size (IEC 60336/93) | 0.5 × 1.0 (small) and 1.0 × 1.0 (large) |

| Tube voltages | 90, 120, 140 kV |

| Tube current | 20 to 500 mA |

| High g forces spiral groove bearing, directly cooled anode |

Another alternative design in MSCT x-ray tubes is the Vectron x-ray tube (see Fig 4-24B), a direct anode cooling x-ray tube based on the Straton x-ray tube direct anode cooling technology. This tube is available from Siemens Healthcare and it operates with tube voltages ranging from 70 to 150 kV in increments of 10 kV. Based on the flying focal spot approach of z-Sharp, the electron beam is now accurately and rapidly deflected, creating two focal spots alternating at 4480 times/s. This feature significantly increases in-plane resolution. The Vectron tube also uses a small focal point of 0.4 mm × 0.5 mm and is capable of up to 0.22 line pairs per centimeter in routine CT scanning without increasing the dose to the patient (Siemens Healthcare, personal communications, 2015).

Filtration: Beam shaping and spectral shaping

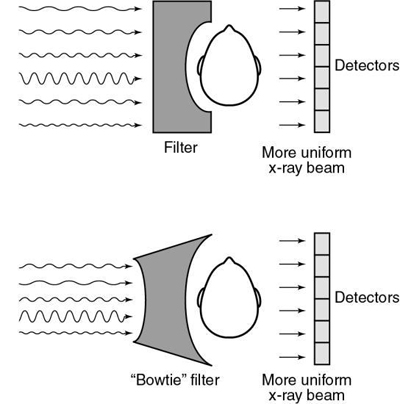

Radiation from x-ray tubes consists of long and short wavelengths. The original experiments in the development of a practical CT scanner used monochromatic radiation to satisfy the Lambert–Beer’s exponential attenuation law. However, in clinical CT, the beam is polychromatic. Because it is essential that the polychromatic beam has the appearance of a monochromatic beam to satisfy the requirements of the reconstruction process, a special filter must be used.

In CT, filtration serves a dual purpose, namely; x-ray beam shaping and x-ray spectral shaping.

X-ray beam shaping

Filtration removes long-wavelength x rays because they do not play a role in CT image formation; instead, they contribute to patient dose. As a result of filtration, the mean energy of the beam increases and the beam becomes “harder,” which may cause beam-hardening artifacts. This is sometimes referred to as spectral shaping (Mozaffary et al., 2019) and will be described in the next subsection.

Recall that the total filtration is equal to the sum of the inherent filtration and the added filtration. In CT the inherent filtration has a thickness of about 3 mm Al-equivalent. The added filtration, on the other hand, consists of filters that are flat or shaped filters made of copper sheets, for example, the thickness of which can range from 0.1 to 0.4 mm (Kalender, 2005).

Filtration in CT shapes the energy distribution across the radiation beam to produce uniform beam hardening when x rays pass through the filter and the object. In Fig. 4.25, the attenuation differs in sections 1, 2, and 3 and the penetration increases in sections 2 and 3. This results from the absorption of the soft radiation in sections 1 and 2, which is referred to as hardening of the beam. Because the detector system does not respond to beam-hardening effects for the circular object shown, “the problem can be solved by introducing additional filtration into the beam” (Seeram, 2009). In the original EMI scanner, this problem was solved with a water bath around the patient’s head. Today, specially shaped filters conform to the shape of the object and are positioned between the x-ray tube and the patient (Fig. 4.26). These filters are called shaped filters, such as the “bowtie” filter, and are usually made of Teflon, a material that has low atomic number and high density, so as not to have a significant impact on beam hardening. “The term ‘bowtie’ applies to a class of filter shapes featuring bilateral symmetry with a thickness that increases with the distance from the center. Bowtie filters compensate for the difference in beam path length through the axial plane of the object such that a more uniform fluence can be delivered to the detector” (Zhang et al., 2013).

X-ray spectral shaping: The use of tin filtration

The use of tin in the x-ray tube filter technology in CT was introduced as a component of DSCT scanners (see Chapters 1 and 13). Tin filtration is also being used in single source CT scanners, as a method of optimizing the dose through spectral shaping (Mozaffary et al., 2019).

The position of the tin filter (thickness of 0.4 mm or 0.6 mm) is shown in Fig. 4.27, located before the standard aluminum “bowtie” filter. The tin (Sn) filter has an atomic number (Z) of 50 and has excellent absorption properties and can provide much better beam hardening (see Chapter 3). In review, beam hardening is a physics-based topic which explains how a filter removes low energy photons from the beam thus increasing its mean energy, resulting in effective beam spectra when used at 100 kV (Woods & Brehm, 2019; Petritsch et al., 2019; May et al., 2017). Such specific filtration (50Sn at 100 kV) results in lower image noise (Woods & Brehm, 2019) and at the same radiation dose with the standard tube voltage of 120 kV.

Collimation

The purpose of collimation in conventional radiography and fluoroscopy is to protect the patient by restricting the beam to the anatomy of interest only. In CT, collimation is equally important because it affects patient dose and image quality (Fig. 4.28). The basic collimation scheme in CT is shown in Fig. 4.28A, with adjustable prepatient, postpatient, and predetector collimators. These detectors must be perfectly aligned to optimize the imaging process. This alignment is accomplished with the fixed collimators, not shown in Fig. 4.28A.

Prepatient collimation design is influenced by the size of the focal spot of the x-ray tube because of the penumbra effect associated with focal spots. The larger the focal spot, the greater the penumbra and the more complicated is the design of the collimators.

In general, a set of collimator sections is carefully arranged to shape the beam, which is proximal to the focal spot. Both proximal and distal (predetector) collimators are arranged to ensure a constant beam width at the detector. Detector collimators also shape the beam and remove scattered radiation. Such removal improves axial resolution as illustrated in Fig. 4.28B, in which the golf ball dimples are apparent. The collimator section at the distal end of the collimator assembly also helps define the thickness of the slice to be imaged. Various slice thicknesses are available depending on the type of scanner.

Some scanners incorporate an antiscatter grid to remove radiation scattered from the patient. This grid is placed just in front of the detectors and it is intended to improve image quality.

Adaptive section collimation

The introduction of MSCT scanners posed some challenges with the design of the collimation scheme, especially as the detectors become wider. The problems are related to what has been referred to as overscanning and overbeaming (Goo, 2012). Whereas overbeaming “relates to x-ray beams being slightly wider than the detector which means that patients are exposed over a small area without the signal being detected” (Kalender, 2014), overscanning “refers to exposure of the patient outside the imaged range which occurs for spiral CT with multi-row detectors at the start and the end of the scan” (Kalender, 2014). These two problems result in increased dose to the patient. For example, overscanning may result in an increase of 5% to 30% in dose keeping the length of the scan in mind (Kalender, 2014).

The problems of overscanning and overbeaming can be solved using a technique called adaptive section collimation (Deak et al., 2009). With adaptive section collimation (see Fig. 10.13) “parts of the x-ray beam exposing tissue outside of the volume to be imaged are blocked in the z-direction by dynamically adjusted collimators at the beginning and at the end of the CT scan” (Deak et al., 2009). These two concepts, overbeaming and overscanning, are discussed in more detail in Chapter 10.

CT detector technology

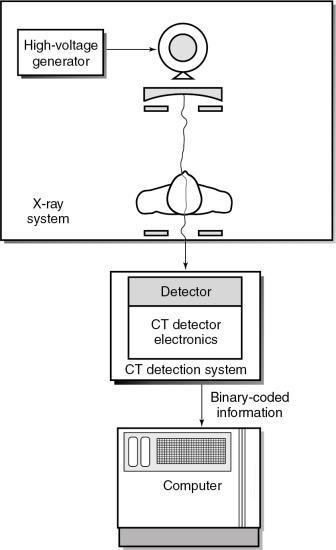

The position of the CT detection system is shown in Fig. 4.29. CT detectors capture the radiation beam from the patient and convert it into electrical signals, which are subsequently converted into binary coded information.

Detector characteristics

Detectors exhibit several characteristics essential for CT image production affecting good image quality, such as efficiency, response time (speed of response), dynamic range, accuracy, stability, resolution, cross talk, and afterglow (Shefer et al., 2013).

Efficiency refers to the ability to capture, absorb, and convert x-ray photons to electrical signals. CT detectors must possess high capture efficiency, absorption efficiency, and conversion efficiency. Capture efficiency refers to the efficiency with which the detectors can obtain photons transmitted from the patient; the size of the detector area facing the beam and distance between two detectors determines capture efficiency. Absorption efficiency refers to the number of photons absorbed by the detector and depends on the atomic number, physical density, size, and thickness of the detector face (Seeram, 2009; Villafana, 1987).

Stability refers to the steadiness of the detector response. If the system is not stable, frequent calibrations are required to render the signals useful.

The response time of the detector refers to the speed with which the detector can detect an x-ray event and recover to detect another event. Response times should be very short (i.e., microseconds) to avoid problems such as afterglow and detector “pile-up.”

The dynamic range of a CT detector is the “ratio of the largest signal to be measured to the precision of the smallest signal to be discriminated (i.e., if the largest signal is 1 μA and the smallest signal is 1 nA, the dynamic range is 1 million to 1)” (Parker & Stanley, 1981). The dynamic range for most CT scanners is about 1 million to 1. The total detector efficiency, or dose efficiency, is the product of the capture efficiency, absorption efficiency, and conversion efficiency (Seeram, 2009; Villafana, 1987).

Afterglow refers to the persistence of the image even after the radiation has been turned off. CT detectors should have low afterglow values, such as less than 0.01%, 100 milliseconds after the radiation has been terminated (Kalender, 2005).

Finally, while resolution is influenced by several factors such as the detector element size, focal spot size, and sampling size (detector pitch), cross talk refers to the amount of signal from one detector element that may leak over into an adjacent detector (Goldman, 2000).

Types

The conversion of x-rays to electrical energy in a detector is based on two fundamental principles (Fig. 4.30). Scintillation detectors (luminescent materials) convert x-ray energy into light, after which the light is converted into electrical energy by a photodetector (see Fig. 4.30A). Figure 4-30B, shows the corresponding electronic symbol. This type of photodetector is referred to as a photovoltaic detector array (PDA) and it is based on front illumination. Current CT scanners now make use of back-illuminated PDA. For a discussion of back-illuminated PDA, the interested reader should refer to Shefer et al. (2013). Gas-ionization detectors, on the other hand, convert x-ray energy directly to electrical energy.

Scintillation detectors

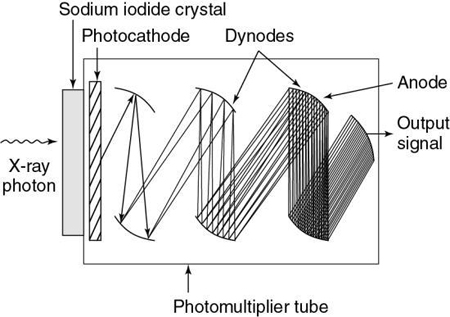

Scintillation detectors are solid-state detectors that consist of a scintillation crystal coupled to a photodiode tube. When x rays fall onto the crystal, flashes of light, or scintillations, are produced. The light is then directed to the photomultiplier, or PM tube. As illustrated in Fig. 4.31, the light from the crystal strikes the photocathode of the PM tube, which then releases electrons. These electrons cascade through a series of dynodes that are carefully arranged and maintained at different potentials to result in a small output signal.

In CT, scintillation detectors must exhibit a high light output, high x-ray stopping power, good spectral match with the photo-detector, short primary decay time (up to tens of μs), low afterglow, radiation damage resistance, light-output stability (time, temperature), compact packaging, and easy machining. In many cases it is uniformity of a certain property that is more important and more challenging to achieve, rather than meeting a required absolute value (Shefer et al., 2013).

As a result, single crystals and polycrystalline ceramics have become popular scintillators for use in CT imaging. Scintillation detectors have experienced significant changes through the years and a few of the highlights of these developments will be described later in this section.

In the past, early scanners used sodium iodide crystals coupled to PM tubes. Because of afterglow problems and the limited dynamic range of sodium iodide, other crystals such as calcium fluoride and bismuth germanate were used in later scanners. Furthermore, solid-state photodiode multiplier scintillation crystal detectors are used (Fig. 4.32). The photodiode is a semiconductor (silicon) whose p-n junction allows current flow when exposed to light. A lens is an essential part of the photodiode and is used to focus light from the scintillation crystal to the p-n junction, or semiconductor junction. When light falls on the junction, electron hole pairs are generated and the electrons move to the n side of the junction while the holes move to the p side. The amount of current is proportional to the amount of light. Photodiodes are normally used with amplifiers because of the low output from the diode. In addition, the response time of a photodiode is extremely fast (about 0.5 to 250 nanoseconds, depending on its design).

Scintillation materials currently used with photodiodes are cadmium tungstate (CdWO4) and a ceramic material made of high-purity, rare earth oxides based on doped rare earth compounds such as yttria (Y,Gd)2O3:Eu, and gadolinium oxysulfide ultrafast ceramic (UFC) (Gd2O2S:Pr,Ce[GOS]; Kalender, 2005; Shefer et al., 2013). More recently GE Healthcare (GE) has made use of what they refer to as the GE Gemstone, a garnet of the type (Lu,Gd, Y,Tb)3(Ga,Al)5O12 detector. This is the first garnet scintillator for use in CT (Shefer et al., 2013). Furthermore, Philips Healthcare makes use of ZnSe: Te in their dual-layer scintillator detectors (Shefer et al., 2013; Xu, 2012).

Usually, these crystals are optically bonded to the photodiodes. The advantages and disadvantages of these two scintillation materials can be discussed in terms of the detector characteristics described earlier. The conversion efficiency and photon capture efficiency of cadmium tungstate are 99% and 99%, respectively, and the dynamic range is 1 million to 1. On the other hand, the absorption efficiency of the ceramic rare earth oxide is 99%, whereas its scintillation efficiency is three times that of CdWO4.

Gas-ionization detectors

Gas-ionization detectors, which are based on the principle of ionization, were introduced in third-generation scanners. The basic configuration of a gas-ionization detector consists of a series of individual gas chambers, usually separated by tungsten plates carefully positioned to act as electron collection plates (Fig. 4.33). When x rays fall on the individual chambers, ionization of the gas (usually xenon) results and produces positive and negative ions. The positive ions migrate to the negatively charged plate, whereas the negative ions are attracted to the positively charged plate. This migration of ions causes a small signal current that varies directly with the number of photons absorbed.

The gas chambers are enclosed by a relatively thick ceramic substrate material because the xenon gas is pressurized to about 30 atmospheres to increase the number of gas molecules available for ionization. Xenon detectors have excellent stability and fast response times and exhibit no afterglow problems. However, their quantum detection efficiency (QDE) is less than that of solid-state detectors. As reported in the past, the QDE is 95% to 100% for crystal solid-state scintillation detectors and 94% to 98% for ceramic solid-state detectors, and it is only 50% to 60% for xenon gas detectors (Arenson, 1995). It is important to note that with the introduction of MSCT scanners with their characteristic multirow detector arrays, gas-ionization detectors and fourth-generation CT systems are not used anymore. MSCT scanners are all based on the third-generation beam geometry (rotate-rotate principle) and use solid-state detector arrays (Kalender, 2005).

Photon-counting detectors

The use of photon counting detectors (PCDs) to detect individual incoming photons from the patient is not a new technology in CT. In a paper published in Radiology, Willemink et al. (2018) stated that “photon-counting CT is an emerging technology with the potential to dramatically change clinical CT. Photon-counting CT uses new energy-resolving x-ray detectors, with mechanisms that differ substantially from those of conventional energy-integrating detectors. Photon-counting CT detectors count the number of incoming photons and measure photon energy. This technique results in higher contrast-to-noise ratio, improved spatial resolution, and optimized spectral imaging. Photon-counting CT can reduce radiation exposure, reconstruct images at a higher resolution, correct beam-hardening artifacts, optimize the use of contrast agents and create opportunities for quantitative imaging relative to current CT technology.”

PCDs offer several advantages including reduced image noise, increase spatial resolution, reduced doses by at least 30% to 40%, and reduced hardening and blooming artifacts, and may have applications in molecular imaging “with targeted nanoparticles resulting in improved early cancer diagnosis and characterization of atherosclerotic plaque composition” (Willemink et al., 2018).

Photon-counting CT scanner-2021

More recently (2021), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared the world’s first photon-counting computed tomography (CT) scanner, the Siemens NAEOTOM Alpha (Siemens Medical Solutions Inc.) in September 2021. This is a major technical innovation in CT technology after 10 years of CT use in the clinical arena. Readers are encouraged to explore the technical details of this new scanner at the Siemens website.

Design innovations

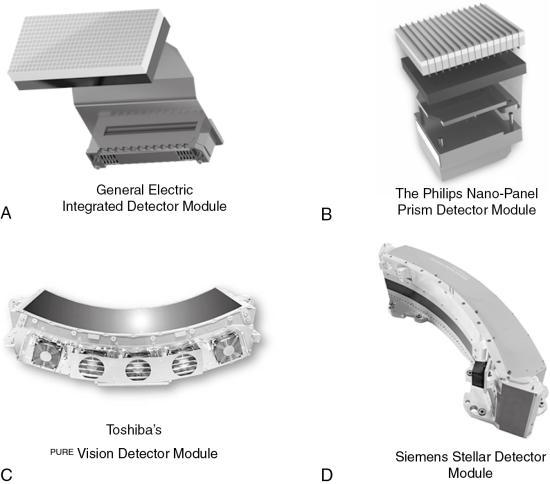

As noted previously, the performance of a CT detector is characterized by efficiency of x-ray absorption and conversion to electrical signals, afterglow, stability, dynamic range, and response time. In an effort to improve on these performance characteristics and produce more efficient detectors for CT imaging, CT manufacturers have introduced several design innovations in an effort to improve clinical image quality (spatial resolution and image noise) in low-dose CT imaging (reduced dose; Shefer et al., 2013). Furthermore, artifact-free images are one of the advantages of these innovations. It is not within the scope of this chapter to describe the details of all of these innovations; however, a few, such as scintillators, miniaturization of the detector electronics, and detector module, will be highlighted.

Generally, CT detectors can be of the conventional energy integration (EI) detector, dual-layer detector, and the direct conversion detector (photon counting detector) as illustrated in Fig. 4.34. The more commonplace CT detectors are of the first type, that is, the EI detector. Innovations involving the first two types will be briefly described next. The photon counting detector will not be described; however, semiconductors such as cadmium telluride (CdTe) and cadmium zinc telluride (CZT) have been used (Xu, 2012) because they can convert x-ray photons directly into electron hole pairs (electric charge) thereby avoiding the signal spread encountered with the light emitted by the commonly used scintillators. In consequence, no optical separation of detector elements is required, and geometric efficiency approaches the desired 100%. The charges generated can be collected within nanoseconds, which makes it possible to count single photons and to determine the energy of each photon. Instead of analogue integration of intensities, digital counts of photons result with little or no influence of electronic noise (Kalender, 2014).

The innovations in CT detector technology have resulted in propriety detectors from four CT manufacturers, listed in Table 4.2, which lists five different types of current CT detectors, including the scintillators used. These propriety detectors are the Gemstone Clarity Detector (GE Healthcare), the NanoPanel Prism Detector (Philips Healthcare), the PURE Vision CT Detector (Toshiba Medical Systems), the Stellar Detector (Siemens Healthcare), and the Quantum Vi Detector (Toshiba Medical Systems). The first four detector modules are shown in Fig. 4.35, which shows the scintillators coupled to the detector modules (which contain the detector electronics). The details of these five detectors are not within the scope of this chapter; however, a brief overview of two of them will be highlighted for the purpose of illustrating the innovations in detector technology that lead to improved image quality in low-dose CT imaging.

| Detector Name | Scintillator | CT Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|

| Gemstone Clarity Detector | Lutetium (Lu)-based garnet (gemstone-rare earth-based oxide) |

General Electric Healthcare |

| NanoPanel Prism Detector |

Top layer: yttrium-based garnet scintillator Bottom layer: GOS |

Philips Healthcare |

| Stellar Detector | UFC |

Siemens Healthcare |

| Quantum Vi Detector | Pr GOS |

Toshiba Medical Systems |

| PURE Vision CT Detector | Pr is an active additive of Toshiba GOS |

Toshiba Medical Systems |

The stellar detector

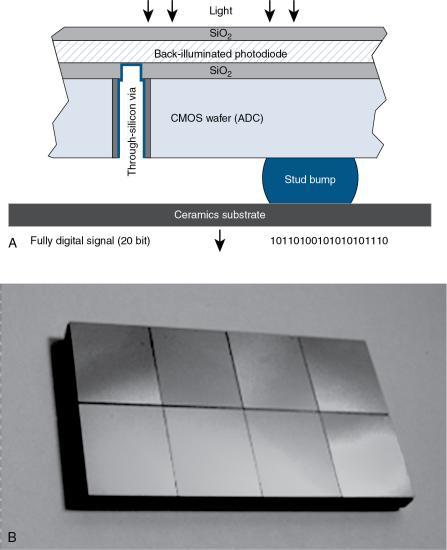

The Siemens Healthcare Stellar Detector falls in the category of the first third-generation CT detectors developed by Siemens Healthcare and is a fully integrated detector for CT imaging. Fig. 4.36A illustrates the major components of the Stellar Detector, which include the UFC scintillator, the back-illuminated photodiode, and the metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) wafer that includes the ADC, and a ceramics substrate. The principle of operation is as follows: the light emitted from the UFC scintillator reaches the backside-illuminated photodiode, and as described by Ulzheimer and Freund (2012), “a digital signal is then produced on the other side of the wafer. This geometry consists of a 3D package of electronic circuits in a through-silicon via (TSV)—a high performance technique for creating vertical connections that pass completely through the silicon wafer.” Fig. 4.36B shows a photo of the Stellar Detector array and, although it is not obvious, the ADC is located below the photodiode array.

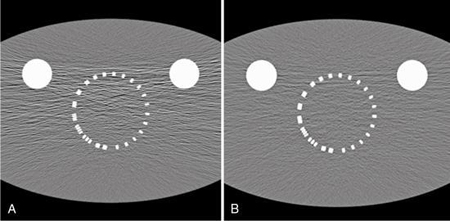

By virtue of its design innovations such as the miniaturization of the electronics with the aid of nanotechnology, the electronics are totally integrated in the photodiode (Siemens TrueSignal Technology): “Stellar detectors can measure smaller signals over a wide dynamic range which reduces the noise in CT images and enhances CT image quality” (Ulzheimer & Freund, 2012). Fig. 4.37 shows a visual comparison of the image quality obtained when using the Stellar Detector compared to a conventional CT detector. Miniaturization of the electronics will be described briefly in the section on Detector Electronics in this chapter.

The NanoPanel prism detector

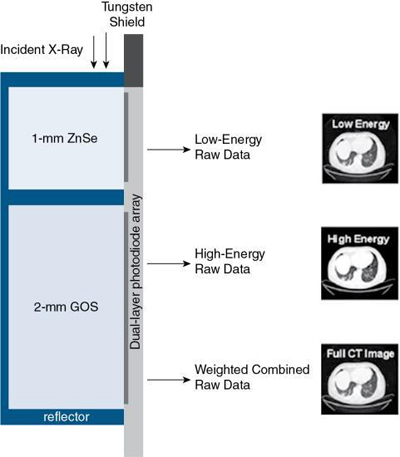

The NanoPanel Prism detector is a Philips Healthcare dual-layer detector based on technology that was first proposed by Brooks and Di Chiro (1978) who published an article titled “Split Detector Computed Tomography: A Preliminary Report” in the journal Radiology. A few years later, Philips Healthcare researchers (Altman et al., 2006; Carmi, 2005) developed another approach to detector-based spectral CT imaging using a dual-layer detector, “through two attached scintillator layers, optically separated, and read by a side-looking, edge-on, silicon photodiode, thin enough to maintain the same detector pitch and geometrical efficiency as a conventional CT detector” (Shefer et al., 2013), as illustrated in Fig. 4.38. The configuration of the dual-layer detector allows for acquisition of both low and high energies for every exposure used in CT imaging.

The dual-layer detector is configured as a 3D tile-patterned arrangement featuring a number of modules in which each module is made up of three highly integrated components (Shefer et al., 2013) as follows:

- 1. A top layer of low-density scintillator (ZnSe), which absorbs low-energy x-ray photons that are subsequently converted to light photons

- 2. A bottom layer of high-density scintillator (GOS), which absorbs high-energy x-ray photons that are subsequently converted to light photons

- 3. Both top and bottom scintillators are coupled to a vertically positioned (edge-on) thin front-illuminated photodiode (FIP), which converts light into electrical signals; the FIP is placed under the scattered radiation grid, so it will not compromise the detector’s geometric efficiency

- 4. An application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) designed for the purpose of ADC, and integration of the two energies, that is, low- and high-energy spectra

The materials used in the construction of the NanoPanel Prism dual-layer detector have been carefully selected and machined to ensure optimum performance in characteristics such as photon conversion efficiency, geometric efficiency, dynamic range, stability, linearity, uniformity, noise, and cross talk, all of which influence the final CT image quality (Gabbai et al., 2013)

Detector-based spectral CT

Spectral CT involves exploiting the transmitted x-ray photons through the patient. Essentially there are two approaches to doing this: energy weighting and material decomposition (Xu, 2012).

While energy weighting requires a photon-counting energy-resolving detector which is capable of detecting the individual photons and measuring the correct photon energies accordingly, material decomposition is to differentiate and characterize different materials and tissues in an examined object by decomposing the energy-dependent linear attenuation coefficients into a linear combination of energy-dependent basis functions and the corresponding basis set coefficients (Xu, 2012).

In CT, essentially two dual-energy methods are used to extract spectral information from the x-rays transmitted through the patient during imaging. These include:

Whereas Siemens Healthcare provides the DSCT system (Krauss, 2011), the fast-kV switching CT system is available from GE Healthcare (Chandra & Langan, 2011).

For a further description of dual-energy CT, the interested reader should refer to a recent paper by Marin et al. (2014), which describes the basic principles of dual-energy CT including the physics of attenuation, different approaches to dual-energy CT (such as consecutive acquisition dual-energy CT, dual-energy CT, fast voltage switching dual-energy CT, and layer detector dual-energy CT), postprocessing tools (nonmaterial-specific display methods, material-specific methods, and energy-specific methods), and clinical applications.

DSCT is described further in Chapter 13.

Multirow/multislice detectors

One major problem with single-slice, single-row detectors is related to the length of time needed to acquire data. The dual-slice, dual-row detector system was introduced to increase the volume coverage speed and thus decrease the time for data collection. CT scanners now use multirow detectors to image multislices during a 360-degree rotation. It is important to realize that other terms such as multidetector and multichannel have been used to describe the detectors for MSCT scanners (Douglas-Akinwande et al., 2006).

Dual-row/dual-slice detectors

In 1992, Elscint introduced the first dual-slice volume CT scanner. The configuration of the dual-row detector system results in faster volume coverage compared with single-row CT systems (Fig. 4.39). This technology uses a dual-row, solid-state detector array coupled with a special x-ray tube based on a double-dynamic focus system. Figure 4-39 also shows the conventional beam geometry (single focal spot, single fan beam, and single detector arc array) and the beam geometry that arises as a result of the dynamic focal spot system. The dynamic focal spot is where the position of the focal spot is switched by a computer-controlled electron-optic system during each scan to double the sampling density and total number of measurements. Twin-beam technology results in the simultaneous scan of two contiguous slices with excellent resolution (Fig. 4.40) because the fan beam ray density and detector sampling are doubled twice, once for each of the two contiguous slices.

Multirow/multislice detectors

The goal of multirow-multislice (MR-MS) detectors is to increase the volume coverage speed performance of both single-slice and dual-slice CT scanners. The MR-MS detector consists of one detector with rows of detector elements (Fig. 4.41). A detector with n rows will be n times faster than its single-row counterpart. MR-MS detectors are solid-state detectors that can acquire 4 to 64 to 320 slices per 360-degree rotation. In addition, the design of these detectors can influence the thickness of the slices.

An MR-MS detector is an array consisting of multiple separate detector rows. For example, these detector rows can range from 2 (Elscint dual-row detector) to 64 detector rows that can image simultaneously 2 to 64 slices, respectively, per 360-degree rotation. It is fairly obvious that the number of slices obtained per 360-degree rotation depends on the number of detector rows. For example, while a 16-detector row scanner can produce 16 images per 360-degree rotation, a 64-detector row scanner will produce 64 slices per 360-degree rotation.

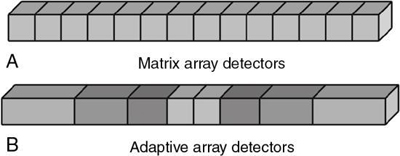

Multirow CT detectors fall into two categories (Fig. 4.42): matrix array detectors and adaptive array detectors (Dalrymple et al., 2007; Flohr et al., 2005; Kalender, 2005). The matrix array detector (Fig. 4-42A), sometimes referred to as a fixed array detector, contains channels or cells, as they are often referred to, that are equal in all dimensions. Because of this, these detectors are sometimes referred to as isotropic in design, that is, all cells are perfect cubes. The adaptive array detector, on the other hand, is anisotropic in design (Kalender, 2005). This means that the cells are not equal; they have different sizes (Fig. 4-42B). The overall goal of isotropic imaging is to produce improved spatial resolution in both the longitudinal and transverse planes (Dalrymple et al., 2007).

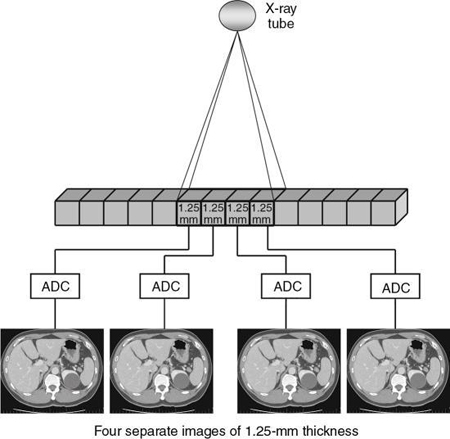

During scanning, the number of slices and the thickness of each slice are determined by the detector configuration used. This configuration “describes the number of data collection channels and the effective section thickness determined by the data acquisition system settings” (Dalrymple et al., 2007). For the sake of simplicity, the detector configuration for a four-row matrix array detector is illustrated in Fig. 4.43 In this example, each detector channel is 1.25 mm and four cells are activated or grouped together to produce four separate images of 1.25-mm thickness per 360-degree rotation. On the other hand, eight cells can be configured to produce four images of 2.5 mm thickness (1.25 mm + 1.25 mm = 2.5 mm) per 360-degree rotation, and so on. Multirow detectors are described further in Chapter 12.

Multirow detectors feature a number of imaging characteristics that are important to the technologist during scanning. Examples of these characteristics include the detector physical materials, number of elements, dynamic range, data sampling rate, slice collimation, slice thickness, scan angles, and scan field of view. Interested readers should refer to CT manufacturers for specific details of their detector characteristics.

Area detectors

As discussed previously, several groups are investigating the use of area detectors for CT imaging and prototypes have been developed and are currently undergoing clinical testing. Two such CT scanners based on area detector technology are the 256-slice CT scanner prototype (Toshiba Aquilion, Toshiba Medical Systems, Japan) and the flat-panel CT scanner prototypes (one from Siemens Medical Solutions, and another from the Koning Corporation, United States).

The 256-slice CT prototype detector

An illustration of the gantry and detector for this scanner is shown in Chapter 1 (Fig 1.16). The detector is a wide area multirow array detector that has 912 channels × 256 segments and a beam width of 128 mm (four times larger than the third-generation 16-slice Toshiba Aquilion CT scanner). This wide beam width makes it possible to scan larger volumes such as the entire heart in a single rotation (Mori et al., 2006; Mori, personal communications, 2006). This scanner is described further in Chapter 13.

The 320-640 wide area detector

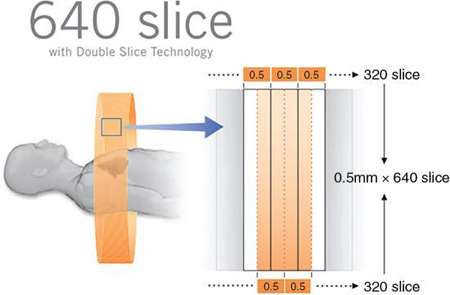

An innovative technology referred to as Double Slice Technology (Canon Medical Systems) allows the reconstruction of 640 slices in a single rotation using a detector configuration of 0.5 × 320 (rows). Slices of 0.5 × 0.25 mm thick (in a single rotation) can be reconstructed resulting in 640 slices per rotation, as illustrated in Fig. 4.44. This is accomplished using ConeXact 3D volume reconstruction algorithm (Canon Medical Systems).

Flat-panel detectors

Flat-panel detectors similar to the ones used in digital radiography are being investigated for use in CT imaging. In this respect, several prototypes have been developed and are currently being evaluated for use in CT imaging. One such prototype is shown in Figure 4-10. Note that the detector is a flat-panel type and is based on the CsI indirect conversion digital radiography detector. More recently, flat-panel detectors are being investigated for use in breast CT, and several prototypes are now undergoing clinical testing (Glick et al., 2007; Kwan et al., 2007). Breast CT is described in Chapter 13.

Detector electronics

Function

The DAS refers to the detector electronics positioned between the detector array and the computer (Fig. 4.45). Because the DAS is located between the detectors and the computer, it performs three major functions: (1) measuring the transmitted radiation beam, (2) encoding these measurements into binary data, and (3) transmitting the binary data to the computer.

Components

The detector measures the transmitted x rays from the patient and converts them into electrical energy. This electrical signal is so weak that it must be amplified by the preamplifier before it can be analyzed further (Fig. 4.46).

The transmission measurement data must be changed into attenuation and thickness data. This process (logarithmic conversion) can be expressed as follows:

or

where μ is the linear attenuation coefficient, I0 is the original intensity, I is the transmitted intensity, and x is the thickness of the object.

Logarithmic conversion is performed by the logarithmic amplifier, and these signals are subsequently directed to the ADC. The ADC divides the electrical signals into multiple parts—the more parts, the more accurate the ADC. These parts are measured in bits: a 1-bit ADC divides the signal into two digital values (21), a 2-bit ADC generates four digital values (22), and a 12-bit ADC results in 4096 (212) digital values. These values help determine the grayscale resolution of the image. Modern CT scanners use 16-bit ADCs.

The final step performed by the DAS is data transmission to the computer. CT manufacturers have introduced optoelectronic data transmission schemes for this purpose because of the continuous rotation of the tube or detector arc and vast amount of data generated.

Optoelectronics refers to the use of lens and light diodes to facilitate data transmission (Fig. 4.47). Several optical transmitters send the data to the optical receiver array so that at least one transmitter and one receiver are always in optical contact. These receivers and transmitters are light-emitting diodes capable of very high rates of data transmission; 50 million bits per second is common.

Design innovations

As described earlier in this chapter, the older conventional second-generation solid-state detectors employed separate electronics coupled to the ADC. A shortcoming of this design includes the use of several electrical components with long conducting wires, which not only increase electrical power consumption but more importantly produce electronic noise, thus compromising CT image quality. These problems are now overcome by another notable recent design innovation for CT detectors—miniaturized detector electronics through the use of integrated microelectronic circuitry. The purpose of such design elements is to reduce not only electronic noise but also to reduce power consumption. One such popular design is referred to as the Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC) for ADC.

The ASIC essentially contains the photodiodes and the ADCs, hence decreasing the distance through which electrical signals must travel. Furthermore, the ASIC design results in a much smaller and compact circuitry compared to second-generation conventional solid-state detectors. The results of the ASIC implementation are the reduction of electronic noise (thus improvement of image quality) and reduced electrical power consumption by the CT detectors.

Detectors such as Gemstone Clarity Detector (GE Healthcare), the Stellar Detector (Siemens Healthcare), PUREVision and the Quantum Vi Detectors (Toshiba Medical Systems), and the NanoPanel Prism Detector (Philips Healthcare) are all based on the integrated microelectronic circuitry design, sometimes also referred to as the integrated DAS circuitry. Fig. 4.48 shows an example of the new detector miniaturized electronics design (Fig 4-48B) compared with the conventional solid-state detector electronics, which includes the ADCs (Fig 4-48A).

In summary, the ASIC component is an innovation in CT detector electronics design that ensures miniaturization of the electronic circuitry resulting in low power consumption and the use of shorter electrical wires that produce low electronic noise. The results of these innovations in CT detector technology are an improved signal-to-noise ratio and hence improved CT image quality, especially in low-dose CT imaging. In this regard, another CT dose optimization technique is the combined use of the new detector with iterative reconstruction algorithms. One such example is illustrated in Fig. 4.49, which shows the visual image clarity of two images of a foot reconstructed with conventional CT technology (Fig. 4.49A) and the other reconstructed using the Stellar Detector (Fig. 4.49B) coupled with the use of an iterative reconstruction algorithm (Sinogram Affirmed Iterative Reconstruction-SAFIRE model-based reconstruction).

Data acquisition and sampling

During data acquisition, the radiation beam transmitted through the patient falls on the detectors. Each detector then measures, or samples, the beam intensity incident on it. If enough samples are not obtained, artifacts, such as streaking (an aliasing artifact), appear on the reconstructed image. To solve this problem, the following methods have been devised to increase the number of samples available for image reconstruction and to thus improve the quality of the image:

- • Slice thickness: The imaging of thin slices helps reduce streaking artifacts related to sampling.

- • Closely packed detectors: When the detectors are closely packed, more detectors are available for data acquisition, which ensures more samples per view and an increase in the total measurements taken per scan. The innovations made to CT detectors recently allow for optimized sampling via improvements in detector characteristics such as fast decay time (primary speed) negligible afterglow. For example, the Gemstone Clarity Detector “has a primary decay time of only 30 microseconds, making it 100 times faster than GOS and... it also has afterglow levels that reach only 25% of GOS levels making it ideal for fast sampling and high resolution” (Chandra, 2008). Fig. 4.50 illustrates the effect of increased sampling on image resolution.