Pain, Temperature Regulation, Sleep, and Sensory Function

Jodi A. Allen

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Rogers/pathophysiology/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Rogers/pathophysiology/

Alterations in sensory function may involve dysfunctions of the general or the special senses. Dysfunctions of the general senses include chronic pain, abnormal temperature regulation, and tactile or proprioceptive dysfunction. Pain is a unique sensory experience that, although universally described as unpleasant, is nonetheless essential to an individual’s survival. Pain provides protection by signaling the presence of disease or injury. Like pain, variations in temperature can signal disease. Fever is a common manifestation of dysfunction and is often the first symptom observed in an infectious or inflammatory condition.

Sleep is a normal cyclic process that restores the body’s energy and maintains normal function. Sleep is so essential to physiologic and psychologic function that sleep deprivation causes a wide range of clinical manifestations. Prolonged deprivation or disruption of sleep ultimately leads to serious dysfunction.

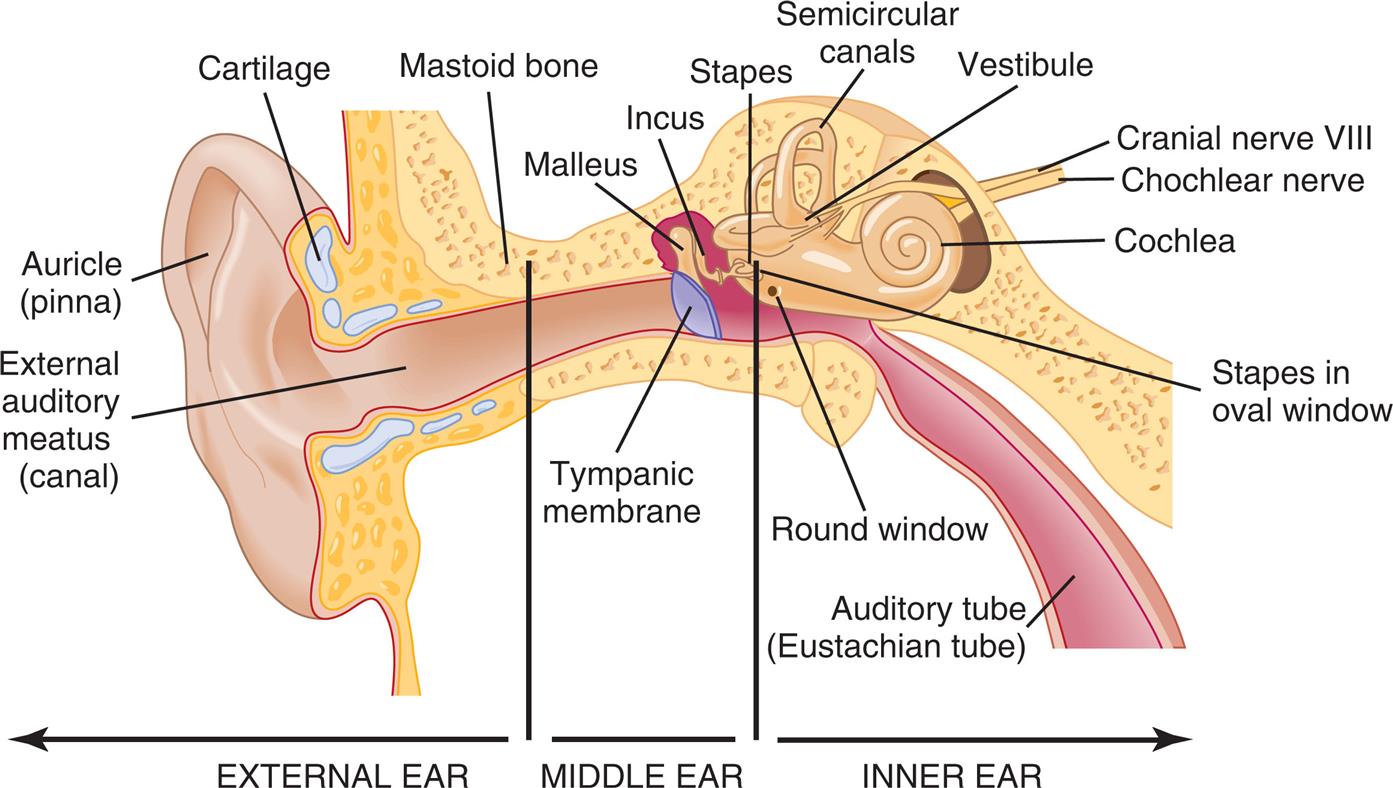

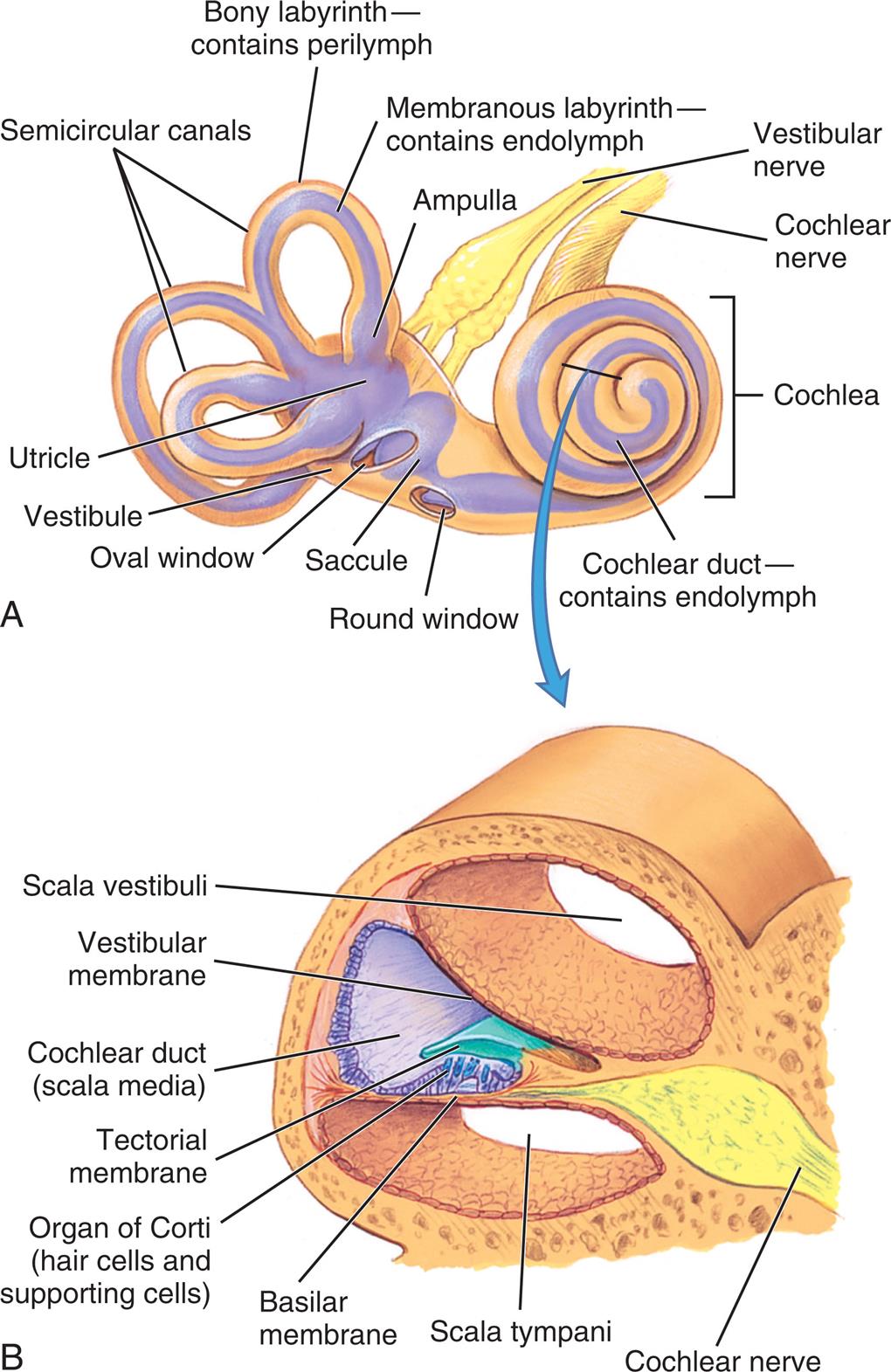

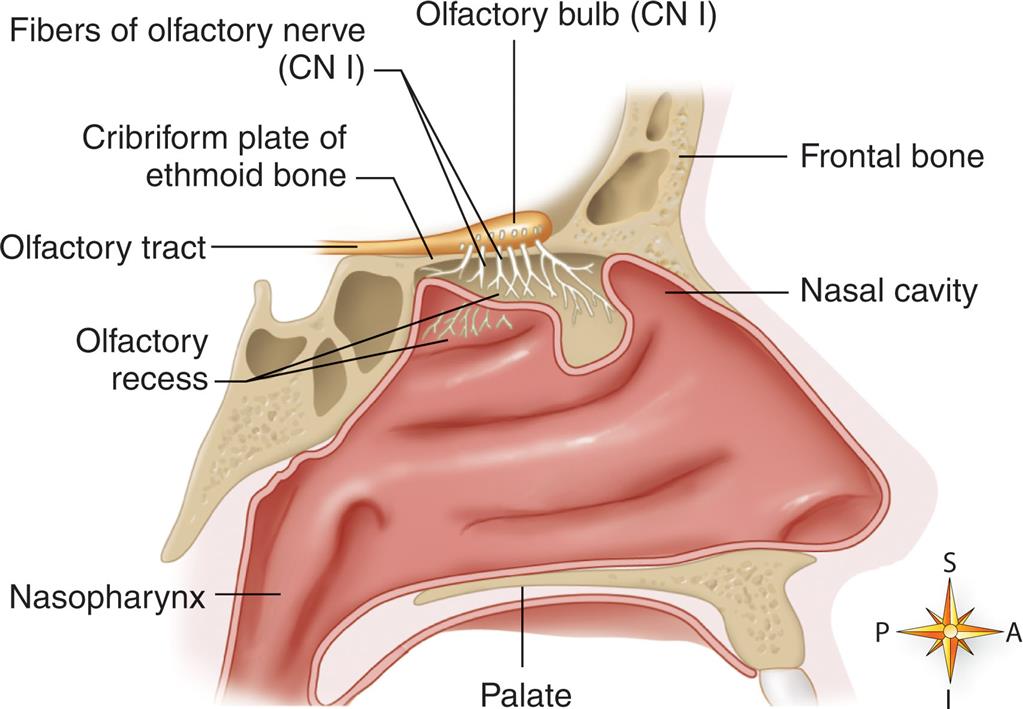

The special senses of vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste are the means by which individuals perceive stimuli that are essential for interacting with the environment. Special sensory receptors are connected to specific areas of the brain through the afferent pathways of the peripheral and central nervous system (CNS). Each of the special senses thus involves a connected system of organs and tissues that receives stimuli and sends sensory messages to areas of the CNS, where they are processed and guide behavior. Dysfunctions of the special senses include visual, auditory, olfactory, and gustatory (taste).

Pain

Pain is one of the body’s most important adaptive and protective mechanisms. It is a complex experience comprised of dynamic interactions among physical, cognitive, spiritual, emotional, and environmental factors and cannot be characterized as only a response to injury. McCaffery defined pain as “whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever he says it does.”1 The International Association for the Study of Pain and the American Pain Society defined pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage.”2 A more recent proposal for the definition of pain is “pain is a mutually recognizable somatic experience that reflects a person’s apprehension of threat to their bodily or existential integrity.”3 Acute pain is protective and promotes withdrawal from painful stimuli, allows the injured part to heal, and teaches avoidance of painful stimuli.

Neuroanatomy of Pain

Three parts of the nervous system are responsible for the sensation, perception, and response to pain:

- 1. The afferent pathways, which begin in the peripheral nervous system (PNS), travel to the spinal gate in the dorsal horn, and then ascend to areas in the diencephalon (thalamus, epithalamus, and hypothalamus) and cortex.

- 2. The interpretive centers located in the subcortical and cortical networks, brainstem, midbrain, diencephalon, and cerebral cortex.

- 3. The efferent pathways that descend from the central nervous system (CNS) back to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.

The processing of potentially harmful (noxious) stimuli through a normally functioning nervous system is called nociception. Nociceptors, or pain receptors, are free nerve endings in the afferent peripheral nervous system. When they are stimulated, they cause nociceptive pain. The cell bodies of nociceptors are located in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) for the body and in the trigeminal ganglion for the face. Nociceptors have a peripheral and central axonal branch that innervates their target organ and the spinal cord, respectively. Nociceptors are unevenly distributed throughout the body, so the relative sensitivity to pain differs according to their location (Table 16.1). Nociceptors respond to different types of noxious stimuli: mechanical (pressure or mechanical distortion), thermal (extreme temperatures), or chemical (acids or chemicals of inflammation, such as bradykinin, histamine, leukotrienes, or prostaglandins). Nociception involves four phases: transduction, transmission, perception, and modulation.4

Table 16.1

Pain transduction is the process of converting a painful stimulus into an electrical signal that is transmitted to the CNS. Transduction begins when nociceptors are activated by a painful stimulus (physical, chemical, or thermal), causing ion channels (sodium, potassium, calcium) on nociceptors to open, creating electrical impulses that travel through axons of two primary types of nociceptors that are transmitted to the spinal cord, brainstem, thalamus, and cortex (see Fig. 15.15).5 The two primary types of nociceptors are A-delta (Aδ) fibers and C fibers. Aδ fibers are larger myelinated fibers that rapidly transmit sharp, well-localized “fast” pain sensations, such as intense heat or a pinprick to the skin. Activation of these fibers causes a spinal reflex withdrawal of the affected body part from the stimulus, before a pain sensation is perceived. C fibers are the most numerous, are smaller, unmyelinated, and are located in muscle, tendons, body organs, and the skin. They slowly transmit dull, aching, or burning sensations that are poorly localized and often constant.

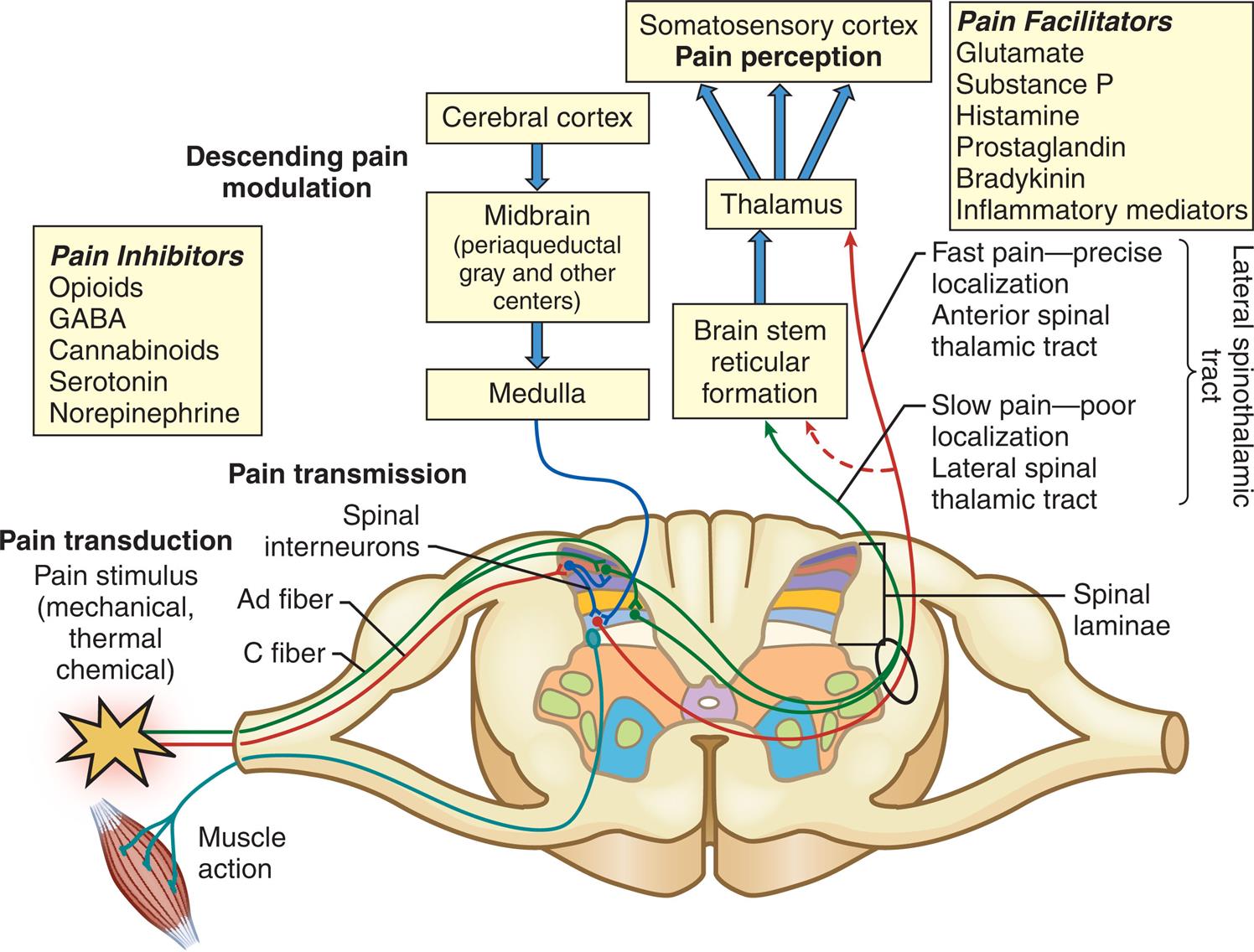

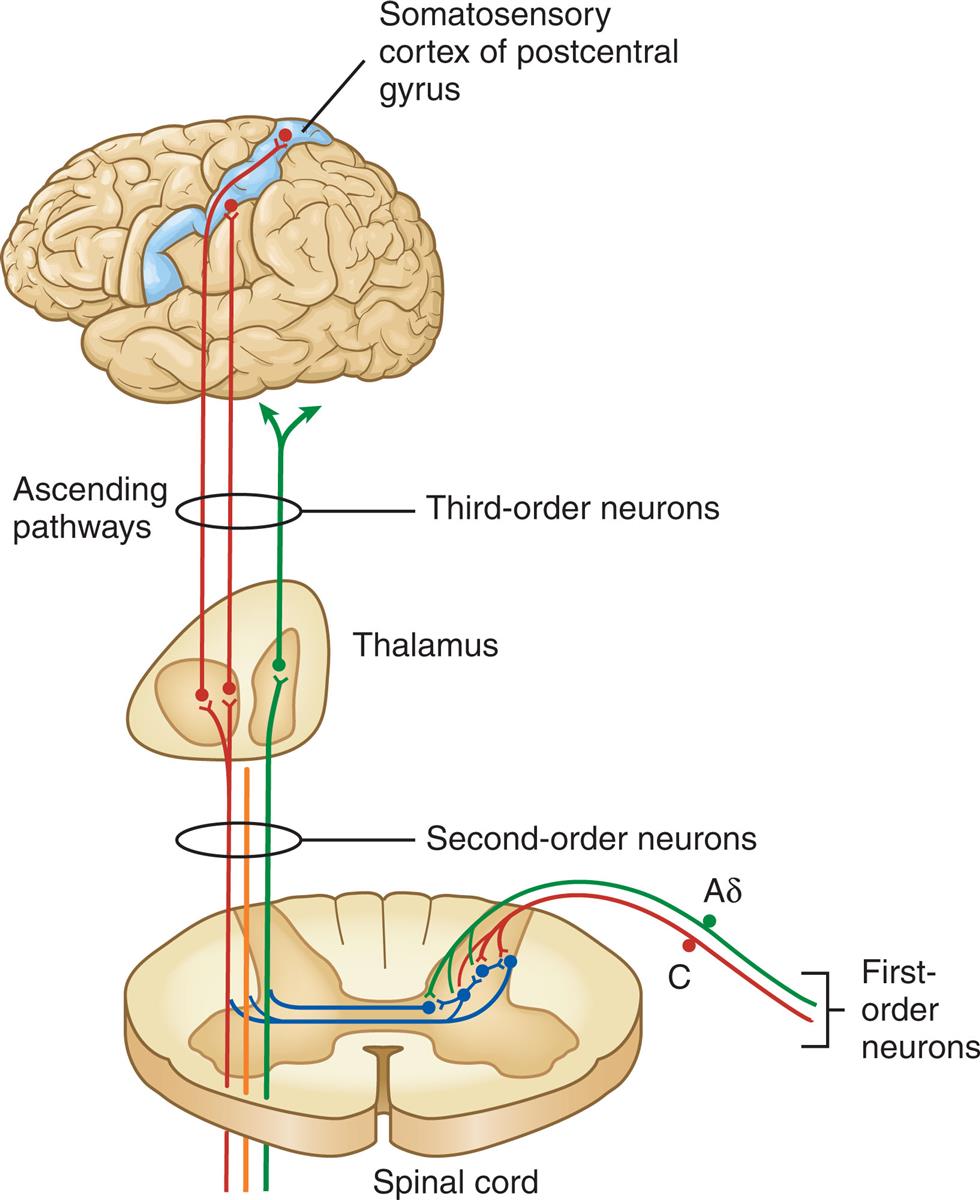

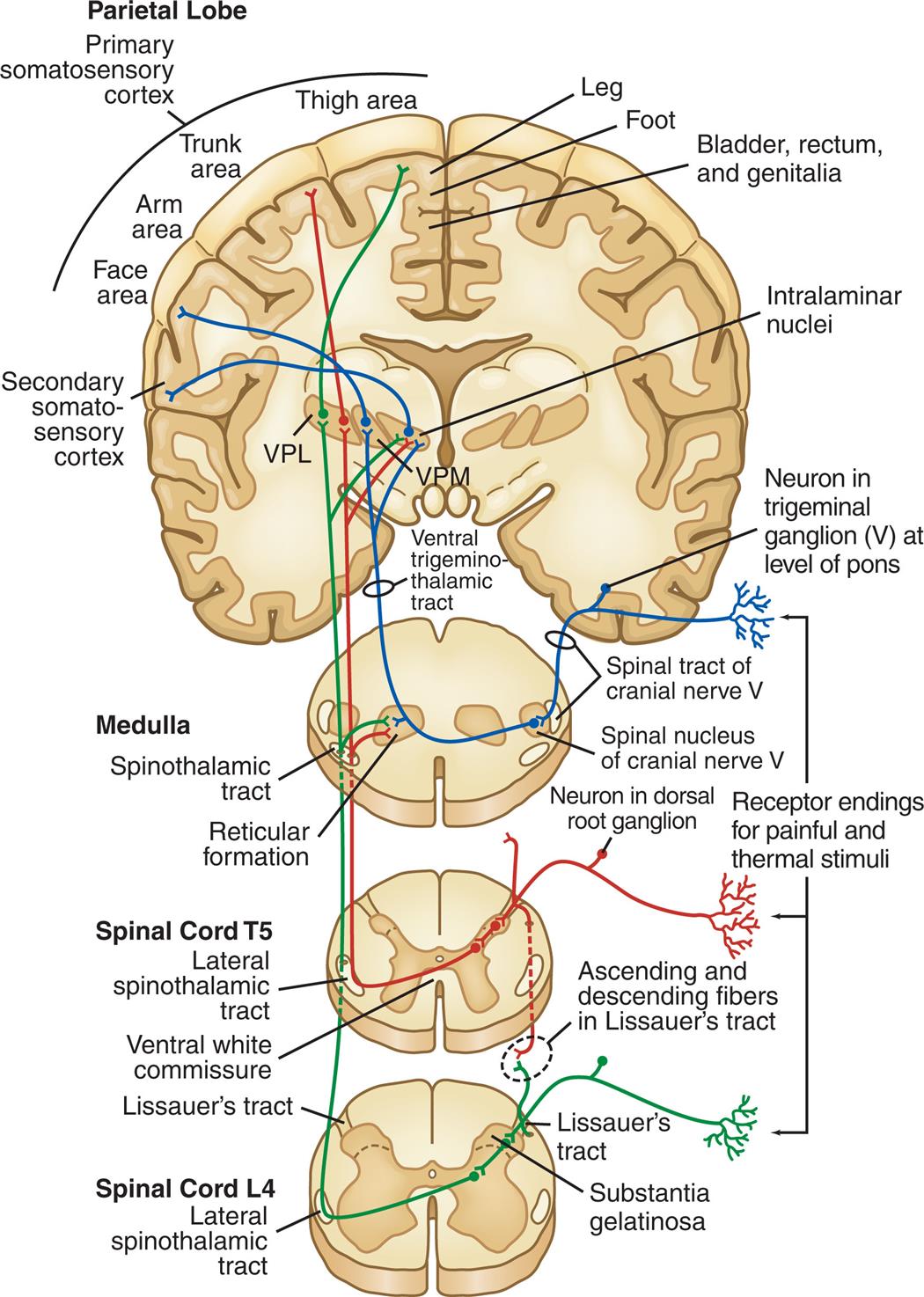

Pain transmission is the conduction of pain impulses along the Aδ and C fibers (primary-order neurons) into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Fig. 16.1). Here they form synapses with excitatory or inhibitory interneurons (second-order neurons) in the substantia gelatinosa of the dorsal horn. The impulses then synapse with projection neurons (third-order neurons), cross the midline of the spinal cord, and ascend to the brain through two lateral spinothalamic tracts (Fig. 16.2). The anterior spinal thalamic tract carries fast impulses for acute sharp pain. The lateral spinothalamic tract carries slow impulses for dull or chronic pain. The fast, sharp pain is perceived first, followed by dull, throbbing pain. These tracts connect to the reticular formation, hypothalamus, thalamus (the major relay station of sensory information), and limbic system. The impulses are then projected to the somatosensory cortex for interpretation of the location and intensity of the pain (Fig. 16.3), and to other areas of the brain for an integrated response to pain.

The Aδ and C fibers synapse in the laminae of the dorsal horn, cross over to the contralateral spinothalamic tract, and then ascend to synapse in the midbrain through the neospinothalamic and paleospinothalamic tracts. Impulses are then conducted to the sensory cortex. Descending pain inhibition is initiated in the cerebral cortex or from the midbrain and medulla.

An illustration accompanied by a flow chart depicts the pain pathway involved in pain transduction, pain transmission, and descending pain modulation. The illustration shows the cross-section through the spinal cord with labels as follows. Pain transduction: Pain stimulus (mechanical, thermal chemical); pain transmission: Spinal interneurons, A fiber, C fiber; spinal laminae. The pathway indicates the pain impulses along with the A fiber and C fibers into the dorsal horn by forming synapses with spinal interneurons. The flow chart represents impulse conducted to the somatosensory cortex through brain stem reticular formation and thalamus and the descending pain modulation in the cerebral cortex to form the midbrain (periaqueductal gray and other centers) and medulla. The anterior spinal thalamic tract carries fast pain through A fiber and the lateral spinal thalamic tract carries slow pain through C fiber. The pain inhibitors are opioids, G A B A, cannabinoids, serotonin, and norepinephrine. Pain facilitators are glutamate, substance P, histamine, prostaglandin, bradykinin, and inflammatory mediators.

Aδ and C fibers comprise the primary, first-order sensory afferents coming into the gate at the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Second-order neurons cross the cord (“decussate”) and ascend to the thalamus as part of the spinothalamic tract. Third-order afferents project to higher brain centers of the limbic system, the frontal cortex, and the primary sensory cortex of the postcentral gyrus of the parietal lobe.

An illustration demonstrates the pathways of nociception involving the first-order, second-order, and third-order neurons that carries action potential from the spinal cord to the somatosensory cortex of postcentral gyrus through the thalamus. The pathway indicates the impulses synapses with a projection of third-order neurons across the midline of the spinal cord, and ascend to the brain through two lateral spinothalamic tracts.

VPL, Ventral posterior lateral thalamic nuclei; VPM, ventral posterior medial thalamic nuclei.

Four series of illustrations depict the central nervous system pathways that mediate sensations of pain and temperature to the primary somatosensory cortex from the spinal cord L 4, spinal cord L 5, and medulla. The illustration of spinal cord L 4 depicts the coronal section of the spinal with labels: lateral spinothalamic tract, substantial gelatinosa, Lissauer's tract. The illustration of spinal cord T 5 depicts the coronal section of the spinal cord with labels: Lateral spinothalamic tract, ventral white commissure, Lissauer's tract, ascending and descending fibers in Lissauer's tract. The illustration of the medulla depicts the coronal section of the spinal cord with labels: Spinothalamic tract, reticular formation, a spinal tract of cranial nerve five, the spinal nucleus of cranial nerve five, a neuron in dorsal root ganglion. The illustration of the parietal lobe depicts the coronal section of the cortex with labels: Primary somatosensory cortex consisting of the face area, arm area, trunk area, thigh area, bladder, rectum and genitalia, leg, foot; secondary somatosensory cortex, ventral trigenmino-thalamic tract, a neuron in trigeminal ganglion five at the level of the pons, intralaminar nuclei. The tracts connect to the reticular formation, hypothalamus, thalamus and limbic system. The impulses are then projected to the somatosensory cortex for interpretation of the location and intensity of the pain and to other areas of the brain for an integrated response to pain.

Pain perception is the conscious awareness of pain, which occurs primarily in the reticular and limbic systems and the cerebral cortex. Interpretation of pain is influenced by many factors, including genetics, cultural preferences, sex roles, age, level of health, and past pain experiences. Three systems interact to produce the perception of pain.6

The sensory-discriminative system is mediated by the somatosensory cortex and is responsible for identifying the presence, character, location, and intensity of pain. The affective-motivational system determines an individual's conditioned avoidance behaviors and emotional responses to pain. It is mediated through the reticular formation, limbic system, and brainstem. The cognitive-evaluative system overlies the individual's learned behavior concerning the experience of pain and therefore can modulate perception of pain. It is mediated through the cerebral cortex. The integration of these three systems is referred to as the “pain matrix”7 or networks of cerebral connectivity.

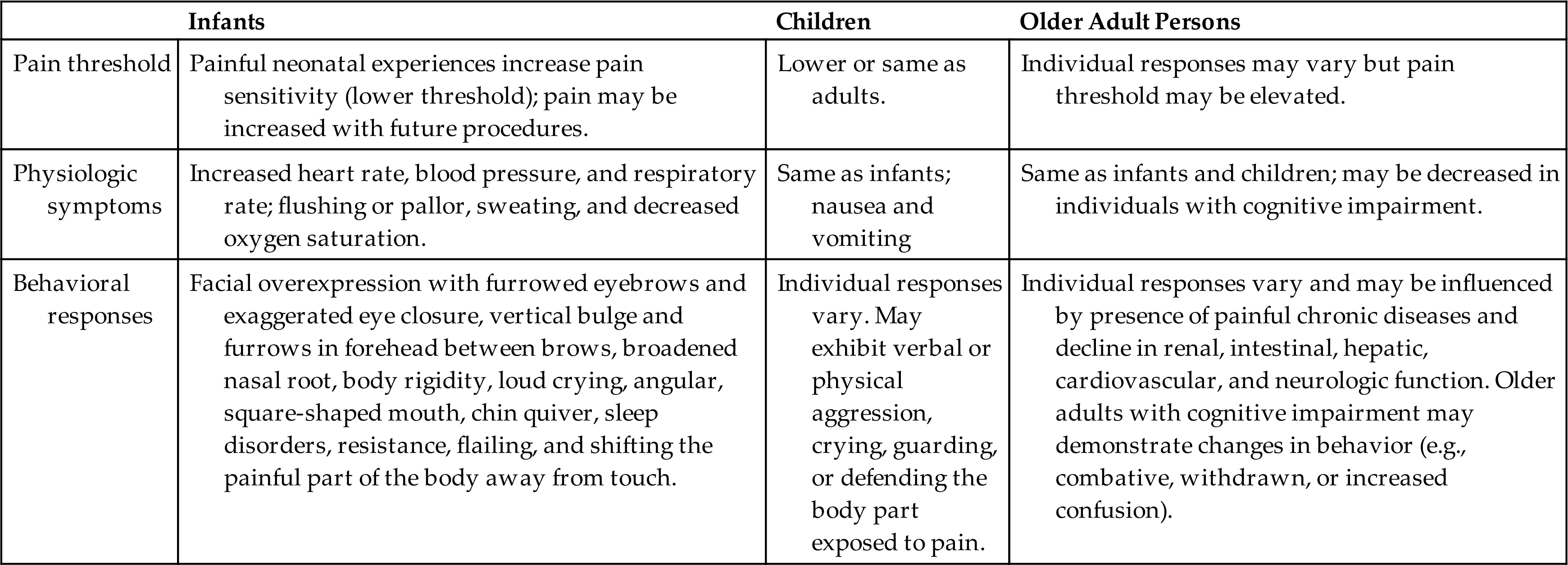

Pain threshold and tolerance are subjective phenomena that influence an individual's perception of pain. They can be influenced by genetics, sex, cultural perceptions, expectations, role socialization, physical and mental health, and age (Table 16.2A).

Table 16.2 A

Data from Anand KJS. Defining pain in newborns: need for a uniform taxonomy? Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(9):1438–1444; Lautenbacher S, et al. Age changes in pain perception: A systematic-review and meta-analysis of age effects on pain and tolerance thresholds. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;75:104–113; Tracy B, Sean Morrison R. Pain management in older adults. Clin Ther. 2013;35(11):1659–1668; Walker SM. Neonatal pain. Paediatr Anaesth. 2014;24(1):39–48.

Pain threshold is defined as the lowest intensity of pain that a person can recognize.2 Intense pain at one location may increase the threshold in another location. For example, a person with severe pain in one knee is more likely to experience less intense chronic back pain (this is called perceptual dominance). Because of perceptual dominance, pain at one site may mask other painful areas. Stress, excessive physical exertion, acupuncture, sexual activity, and other factors can increase the levels of circulating neuromodulators, thereby raising the pain threshold.

Pain tolerance is defined as the greatest intensity of pain that a person can endure.2 It varies greatly among people and in the same person over time because of the body's ability to respond differently to noxious stimuli. Pain tolerance generally decreases with repeated exposure to pain, fatigue, anger, boredom, apprehension, and sleep deprivation and may increase with alcohol consumption, persistent use of opioid medications, hypnosis, distracting activities, and strong beliefs or faith.

Pediatric ConsiderationsPain Perception of Infants and Children

Infants and children have the anatomic and functional ability to perceive pain. However, in the pediatric population, pain is frequently under-recognized and inadequately treated.

Pain pathways and cortical and subcortical centers for pain perception, as well as neurochemicals associated with pain transmission and modulation, are functional in preterm and newborn infants. Alterations in biological factors (e.g., peripheral and central somatosensory function and modulation, brain structure and connectivity) and psychosocial factors (e.g., gender, coping style, mood, and parental response) that influence pain have been identified in children and young adults born very preterm or extremely preterm.8

Repetitive, painful experiences and prolonged exposure to analgesic drugs in preterm infants may permanently alter developing synaptic and neuronal pain-processing networks, causing irreversible hypersensitivity to pain with subsequent injury. Alterations occur in both the excitatory and inhibitory pathways in the spinal cord and descending inhibitory processing from the brainstem. When children are not sufficiently treated for pain, stress hormones are released into their systems, resulting in increased catabolism, immunosuppression, and hemodynamic instability.9

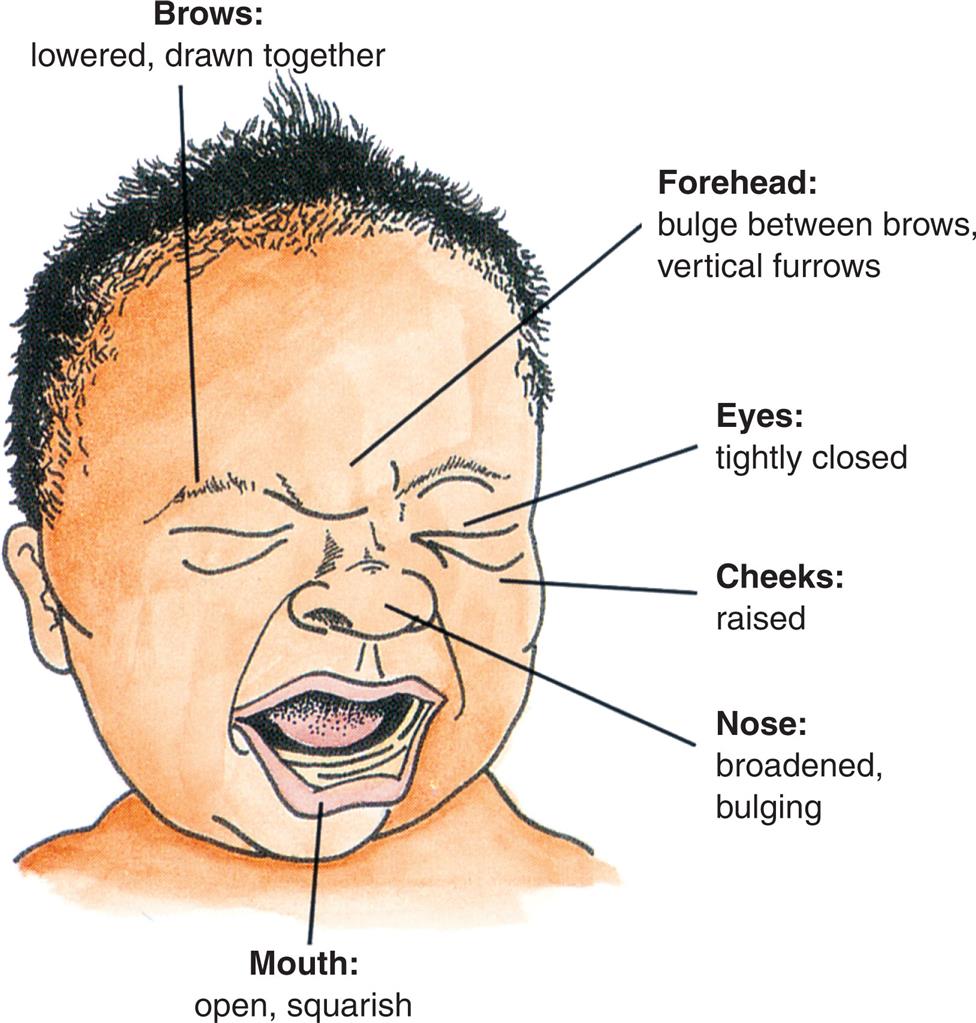

Facial overexpression with furrowed eyebrows and exaggerated eye closure, body rigidity, loud crying, sleep disorders, resistance, and shifting the painful part of the body away from touch are the most consistent expressions of pain in infants.9 There may be finger clenching, writhing, back arching, and head banging.

An illustration of the anterior profile of a crying infant depicts the facial expression of pain labeled as follows. Brows: Lowered, drawn together. Forehead: bulge between brows, vertical furrows; eyes: Tightly closed; cheeks: raised; Nose: broadened bulging.

Toddlers in pain may exhibit verbal or physical aggression and crying, or may guard or defend the body part exposed to pain. Children, like adults, have highly individual responses to pain. Any behavioral and physiologic indicators of pain must be carefully and accurately assessed and adequately treated for children of all ages. Physiologic responses in all age groups may include increases in heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate; flushing or pallor; sweating; and decreased oxygen saturation.

Assessment of pain includes a thorough pain history received from the child and/or parent, exploring the pain quality, characteristics, location, onset, duration, aggravating and alleviating factors, and impact on function. The measurement of pain severity should be done routinely using a developmentally appropriate validated tool. Commonly used tools are listed in Table 16.2B with specified age ranges for the tool.

Table 16.2B

| Pain Assessment Tool | Age Range |

|---|---|

| Revised Premature Infant Pain Profile (PIPP-R)1 | Less than 28 weeks to greater than 36 weeks gestational age |

| Revised Face Legs Activity Cry and Consolability (r-FLACC) scale2 | 2 months to 7 years of age |

| Faces Pain Scale—Revised (FPS-R)3 | 4 years of age and older |

| Children and Infants Postoperative Pain Scale (CHIPPS)4 [Paediatr Anaesth. 2000;10(3): 303–318.] | Under 5 years of age |

| Numerical Rating Scale (NRS)5 | 8 years of age and older |

1Stevens BJ, Gibbins S, Yamada J, et al. The premature infant pain profile-revised (PIPP-R). Clin J Pain. 2014;30(3):238–243.

2Malviya S, Voepel-Lewis T, Burke C, et al. The revised FLACC observational pain tool: improved reliability and validity for pain assessment in children with cognitive impairment. Pediatr Anesth. 2006;16(3):258–265.

3Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, et al. The faces pain scale-revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93(2):173–183.

4Büttner W, Finke W. Analysis of behavioural and physiological parameters for the assessment of postoperative analgesic demand in newborns, infants and young children: a comprehensive report on 7 consecutive studies. Paediatr Anaesth. 2000;10(3):303–318.

5Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(1):17–24.

Data from Zieliński J, Morawska-Kochman M, Zatoński T. Pain assessment and management in children in the postoperative period: a review of the most commonly used postoperative pain assessment tools, new diagnostic methods and the latest guidelines for postoperative pain therapy in children. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2020;29(3):365–374. doi:10.17219/acem/112600. PMID: 32129952.

There are biological and psychosocial factors that influence the perception and severity of pain. Alterations in biological factors, such as peripheral and central somatosensory function, pain modulation, brain structure, and connectivity, have been identified in children and young adults born very preterm or extremely preterm and play a role in pain. There are also psychosocial factors such as gender, coping style, mood, and parental response that influence pain.8

Geriatric Considerations Aging and Pain

Pain in the older adult population is highly prevalent and is a complex issue to both identify and treat. Some older adults have an increased pain threshold while others have a decreased pain tolerance; both factors play a role in the identification and treatment of pain.10,11 It is important to assess the presence of pain in elderly persons with cognitive decline, as it is often neglected, underreported, underestimated, misdiagnosed, and not adequately treated.12 Inadequate assessment of pain or lack of proper pain management is associated with adverse outcomes including depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and mood changes, which often lead to significant suffering, disability, and social isolation with greater costs and burden to the health care system.10 Chronic and somatic pain have been shown to negatively affect the degree of frailty.13 The most frequent pain conditions in older adults are chronic unspecified joint pain, chronic back pain, and chronic neck pain.12 Pain must be accurately treated in relation to its effect on cognitive function, coexisting disease, drug interactions, other reactions to treatment, and an individual’s ability to express pain and maintain safety. Treatment is often compounded by the high prevalence of polypharmacy within this population. Pharmacotherapies used for pain management in older adults are usually only partially effective and are often limited by side effects.10 Older adults prescribed pharmacological treatment must be monitored carefully for any alterations in cognition, liver and renal function, physiological changes, and possible drug interactions.12

Pain Modulation

Pain modulation involves many different facilitatory and inhibitory mechanisms that increase or decrease the transmission of pain signals throughout the nervous system. Mechanisms include neurotransmitters and central and spinal pathways. Depending on the mechanism, modulation can occur before, during, or after pain is perceived.14 Analgesic drugs, anesthesia, and nonpharmacologic interventions such as transcutaneous nerve stimulation, acupuncture, hypnosis, and physical therapies are examples of strategies for enhancing pain modulation.

Neurotransmitters of Pain Modulation

A wide variety of neurotransmitters act to modulate control over transmission of pain impulses in the periphery, spinal cord, and brain. The peripheral triggering mechanisms that initiate release of excitatory neurotransmitters include tissue injury (prostaglandins, histamine, bradykinin) and chronic inflammatory lesions (lymphokines). Glutamate, aspartate, substance P, and calcitonin are common excitatory neurotransmitters in the brain and spinal cord. These substances sensitize nociceptors by reducing the activation threshold, leading to increased responsiveness of nociceptors.

Inhibitory neurotransmitters in the CNS include gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glycine. Norepinephrine and 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) contribute to pain inhibition in the CNS but can excite peripheral nerves.

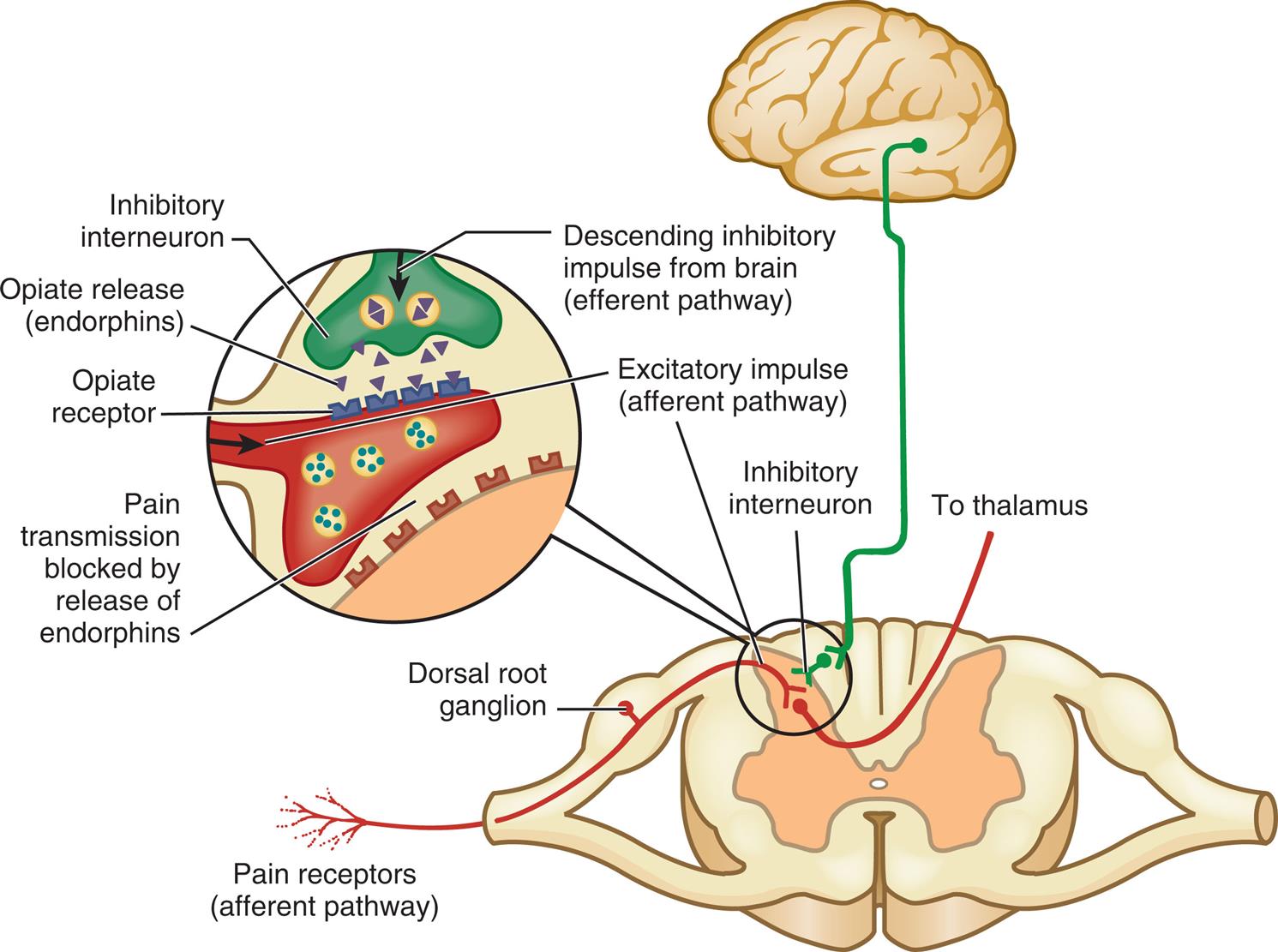

Endogenous opioids are a family of morphine-like neuropeptides that inhibit transmission of pain impulses in the periphery, spinal cord, and brain by binding with specific opioid receptors (mu [μ], kappa [κ], and delta [δ]) on neurons. They inhibit ion channels, preventing the release of excitatory neurotransmitters, such as substance P and glutamate, in the dorsal horn. In the midbrain they influence descending inhibitory pathways (Fig. 16.4).15 In peripheral inflamed tissue, opioids are produced and released from immune cells and activate opioid receptors on sensory nerve terminals.16 Opioid receptors are widely distributed throughout the body and are responsible for general sensations of well-being and modulation of many physiologic processes, including control of respiratory and cardiovascular functions, stress and immune responses, gastrointestinal function, reproduction, and neuroendocrine control.17,18

An illustration depicts the descending inhibitory impulse from the brain (efferent pathway) through the thalamus synapses at the inhibitory interneuron in the dorsal ganglion (afferent pathway) along with excitatory impulse (afferent pathway) and stimulates the opiate to release endorphins. The released endorphins activate the opioid receptor which inhibits pain transmission.

Enkephalins are the most prevalent of the natural opioids and bind to δ opioid receptors. Endorphins (endogenous morphine) are produced in the brain. The best-studied endorphin is β-endorphin, which binds to μ receptors and is purported to produce the greatest sense of exhilaration as well as substantial natural pain relief. Dynorphins are the most potent of the endogenous opioids, binding strongly with κ receptors to impede pain signals. Paradoxically, they play a role in neuropathic pain and in mood disorders and drug addiction. Endomorphins bind with μ receptors and have potent analgesic effects. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ is an opioid that induces pain or hyperalgesia but does not interact with opioid receptors. The nociceptin receptor is widely distributed throughout the PNS and CNS and is associated with numerous biological functions, including immune regulation, mood, feeding, muscle contractility, heart rate, and emotion.

Synthetic and natural opiates have pharmacologic actions similar to morphine and bind as direct agonists to the opioid receptors. Morphine has a 50 times higher affinity for μ receptors in comparison with other opioids. Naloxone is the only clinically used opioid receptor antagonist, with a higher affinity for the µ receptors than for the other receptors.

Endocannabinoids are synthesized from phospholipids and are classified as eicosanoids. They activate cannabinoid CB1 (primarily in the CNS) and CB2 receptors (primarily in immune tissue [e.g., the spleen]) to modulate pain and other functions, including memory, appetite, immune function, sleep, stress response, thermoregulation, and addiction. CB1 receptors decrease pain transmission by inhibiting release of excitatory neurotransmitters in the spinal dorsal horn, periaqueductal gray (PAG; the gray matter surrounding the cerebral aqueduct), thalamus, rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM), and amygdala. Cannabis (marijuana) produces a resin containing cannabinoids. Cannabinoids are analgesic in humans, but their use is limited by their psychoactive and addictive properties. Work is in progress to develop cannabinoid receptor agonists that do not have addictive side effects.19,20

Pathways of Modulation

Descending inhibitory and facilitatory pathways inhibit or facilitate pain. Inhibitory pathways can activate opioid receptors and inhibit release of excitatory neurotransmitters, facilitate release of inhibitory neurotransmitters, or stimulate inhibitory interneurons. Afferent stimulation of particularly the ventromedial medulla and PAG in the midbrain stimulates efferent pathways, which inhibit ascending pain signals at the dorsal horn. The RVM stimulates descending pathways that facilitate or inhibit pain in the dorsal horn.

Segmental pain inhibition occurs when A-beta (Aβ) fibers (large myelinated fibers that transmit touch and vibration sensations) are stimulated and the impulses arrive at the same spinal level or segment as impulses from Aδ or C fibers. They stimulate an inhibitory interneuron and decrease pain transmission. An example is rubbing an area that has been injured to relieve pain.

Diffuse noxious inhibitory control (DNIC) is an endogenous inhibitory pain system that involves a spinal-medullary-spinal pathway. Pain is relieved when two noxious or painful stimuli occur at the same time from different sites (pain inhibiting pain). The efficacy of DNIC is evaluated clinically by testing subjective responses to pain using conditioned pain modulation (CPM). A CPM test uses a consistent protocol to deliver a measurable test pain stimulus at one site before and during or after the application of a measurable conditioning pain stimulus at a comparable site (e.g., the arms). A subjective pain intensity rating scale (i.e., 1 to 10) is used to measure intensity of pain at both sites. The conditioning pain stimulus is expected to affect the pain experience of the test stimulus. Use of CPM assessments can be helpful in determining an individual’s endogenous pain inhibitory capacity and for managing acute or chronic pain.21,22Expectancy-related cortical activation (placebo effect [beneficial expectations] or nocebo effect [adverse expectations]) can exert control over analgesic systems to attenuate or intensify pain.23 In other words, cognitive expectations can cause real, measurable physiologic effects that share some of the same descending pain pathways as the pain modulatory systems (see Emerging Science Box: Pain Management With Pharmacogenics).

Clinical Descriptions of Pain

Pain can be described in a variety of ways. Due to the complex nature of pain, many terms overlap, and more than one description is often used. The broad categories of pain are summarized in Box 16.1. Some of the most common clinical pain presentations are summarized here.

Acute pain (nociceptive pain) is a normal protective mechanism that alerts the individual to a condition or experience that is immediately harmful to the body and mobilizes the individual to take prompt action to relieve it. Acute pain is transient, usually lasting seconds to days, sometimes up to 3 months. It begins suddenly and is relieved after the chemical mediators (usually related to inflammation) that stimulate pain receptors are removed. Stimulation of the autonomic nervous system results in physical manifestations, including increased heart rate, hypertension, diaphoresis, and dilated pupils. Anxiety related to the pain experience, including its cause, treatment, and prognosis, is common, as is the hope of recovery and expectation of limited duration.

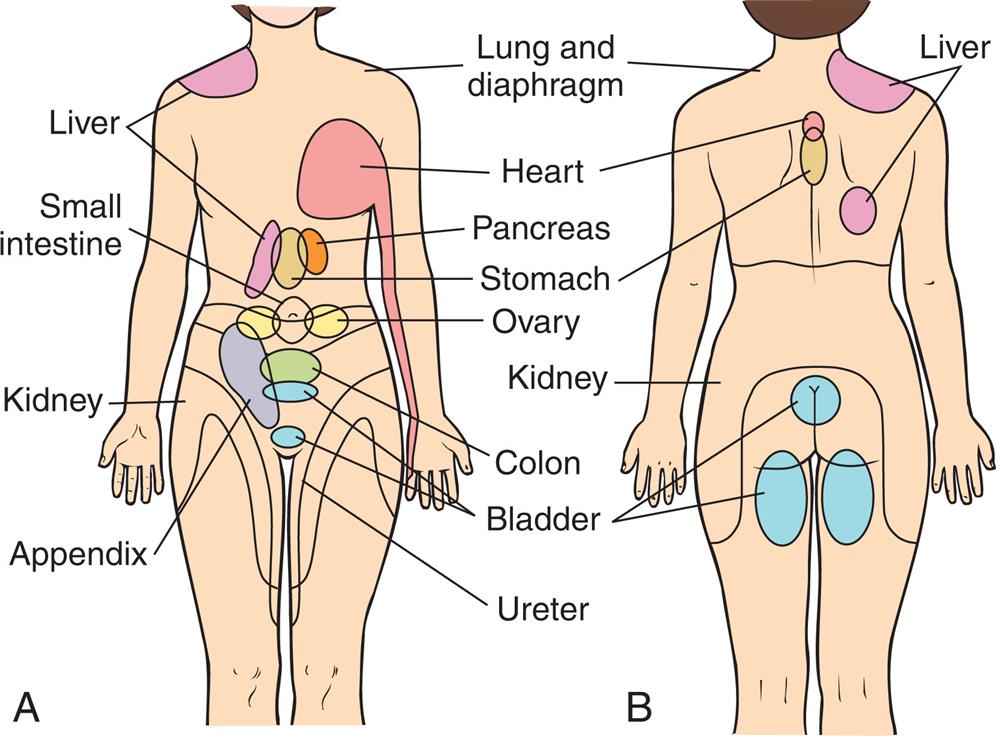

Acute pain arises from cutaneous, deep somatic, or visceral structures and can be classified as (1) somatic, (2) visceral, or (3) referred. Somatic pain arises from the skin (i.e., from an abrasion or a laceration), joints (pain from arthritis or injured tendons), and muscles (strain from overuse or muscle injury). It is either sharp and well localized (especially fast pain carried by Aδ fibers) or dull, aching, throbbing, and poorly localized, as seen in polymodal unmyelinated C fiber transmissions. Visceral pain is transmitted by C fibers and refers to pain in internal organs and the lining of body cavities. It tends to be poorly localized with an aching, gnawing, throbbing, or intermittent cramping quality. It is carried by sympathetic fibers and is associated with nausea and vomiting, hypotension, and, in some cases, shock. Visceral pain often radiates (spreads away from the actual site of the pain) or is referred. Examples of conditions that cause visceral pain include gallstones, pancreatitis, kidney stones, bowel obstruction, appendicitis, and bladder infection. Referred pain is felt in an area removed or distant from its point of origin—the area of referred pain is supplied by the same spinal segment as the actual site of pain. Referred pain can be acute or chronic. Impulses from many cutaneous and visceral neurons converge on the same ascending neuron, and the brain cannot distinguish between the different sources of pain. Because the skin has more receptors, the painful sensation is experienced at the referred site instead of at the site of origin. Referred pain can be acute or chronic. For example, the pain of pancreatitis may be felt in the right shoulder or scapula, or pain from the heart may be referred to the left shoulder or arm. Fig. 16.5 illustrates common areas of referred pain and their associated sites of origin.

(A) Anterior view. (B) Posterior view.

Two illustrations, A and B, depict the common areas of referred pain and their associated sites of origin labeled. Illustration A shows the anterior view of the human with the common areas of referred pain labeled as follows. Liver, small intestine, kidney, appendix, lung and diaphragm, heart, pancreas, stomach, ovary, colon, bladder, and ureter. Illustration B shows the posterior view of the human with common areas of referred pain labeled as follows. Lung and diaphragm, heart, stomach, kidney, bladder, and liver.

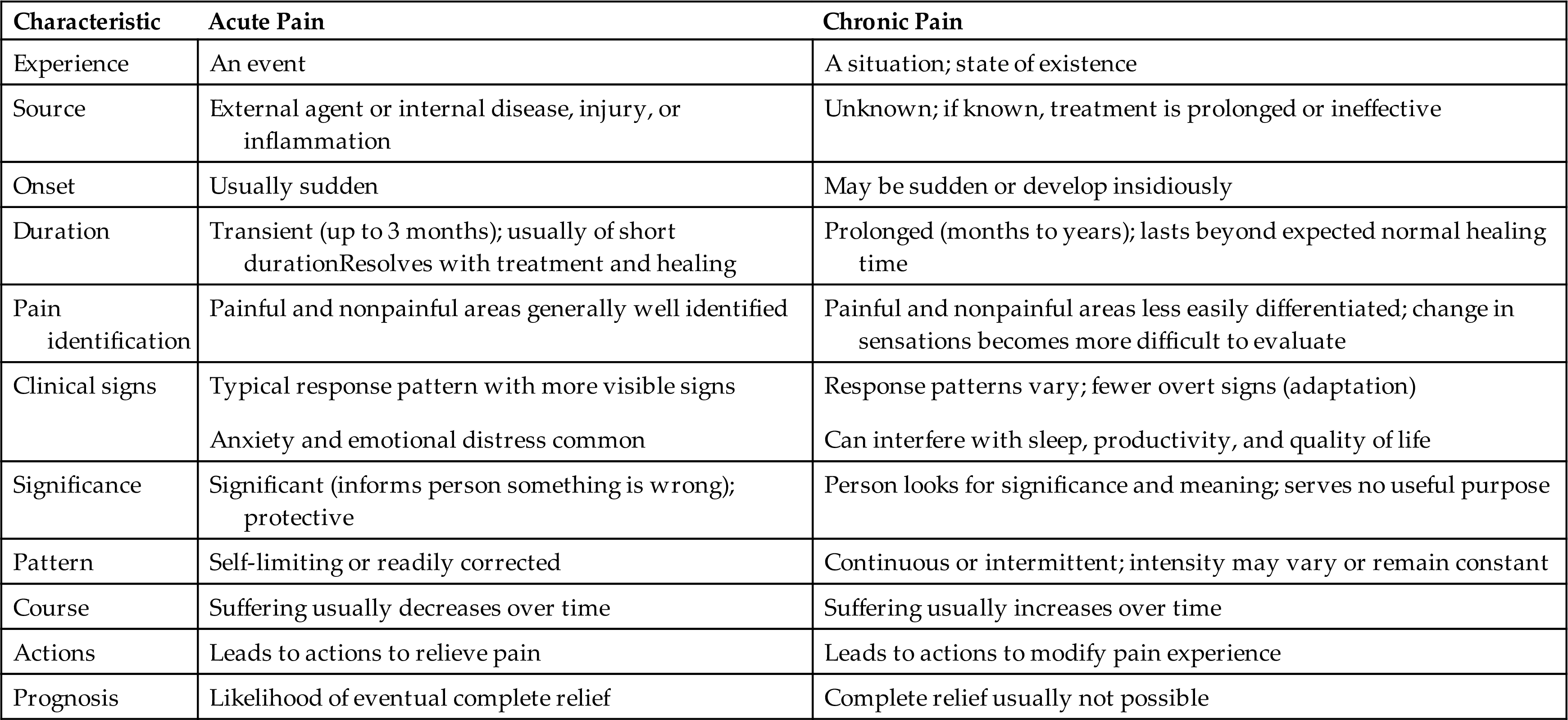

Chronic or persistent pain has been defined as lasting for more than 3 to 6 months in adults and is pain lasting well beyond the expected normal healing time. It varies with the type of injury, is different among age groups, and produces varietal levels of disability.24

Chronic or persistent pain serves no purpose, is poorly understood, and causes suffering. It often appears to be out of proportion to any observable tissue injury. It may be ongoing (e.g., low back pain) or intermittent (e.g., migraine headaches). Changes in the PNS and CNS that cause dysregulation of nociception and pain modulation processes (peripheral and central sensitization) are thought to lead to chronic pain (see the discussion of neuropathic pain later in this section).

Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated brain changes in individuals with chronic pain, which may lead to cognitive deficits and decreased ability to cope with pain.25,26 These negative manifestations of chronic pain are thought to be due, in part, to the stress of coping with continuous pain and may be reversible when pain is controlled. Because it is not yet possible to predict when acute pain will develop into chronic pain, early treatment of acute pain is encouraged. Comparison of acute and chronic pain is summarized in Table 16.3.

Table 16.3

Physiologic responses to intermittent chronic pain are similar to those for acute pain, whereas persistent pain allows for physiologic adaptation, producing a normal heart rate and blood pressure. This leads many to mistakenly conclude that people with chronic pain are malingering because they do not appear to be in pain. As chronic pain progresses, certain behavioral and psychologic changes often emerge, including depression, difficulty eating and sleeping, preoccupation with the pain, and avoidance of pain-provoking stimuli.27 The desire to relieve pain and the need to hide it become conflicting drives for those with chronic pain, who fear being labeled complainers.28 Chronic pain is perceived as meaningless and is often associated with a sense of hopelessness as more time elapses; no relief seems possible. Some of the chronic pain syndromes are listed in Table 16.4. Chronic pain associated with specific organ systems is discussed in later chapters.

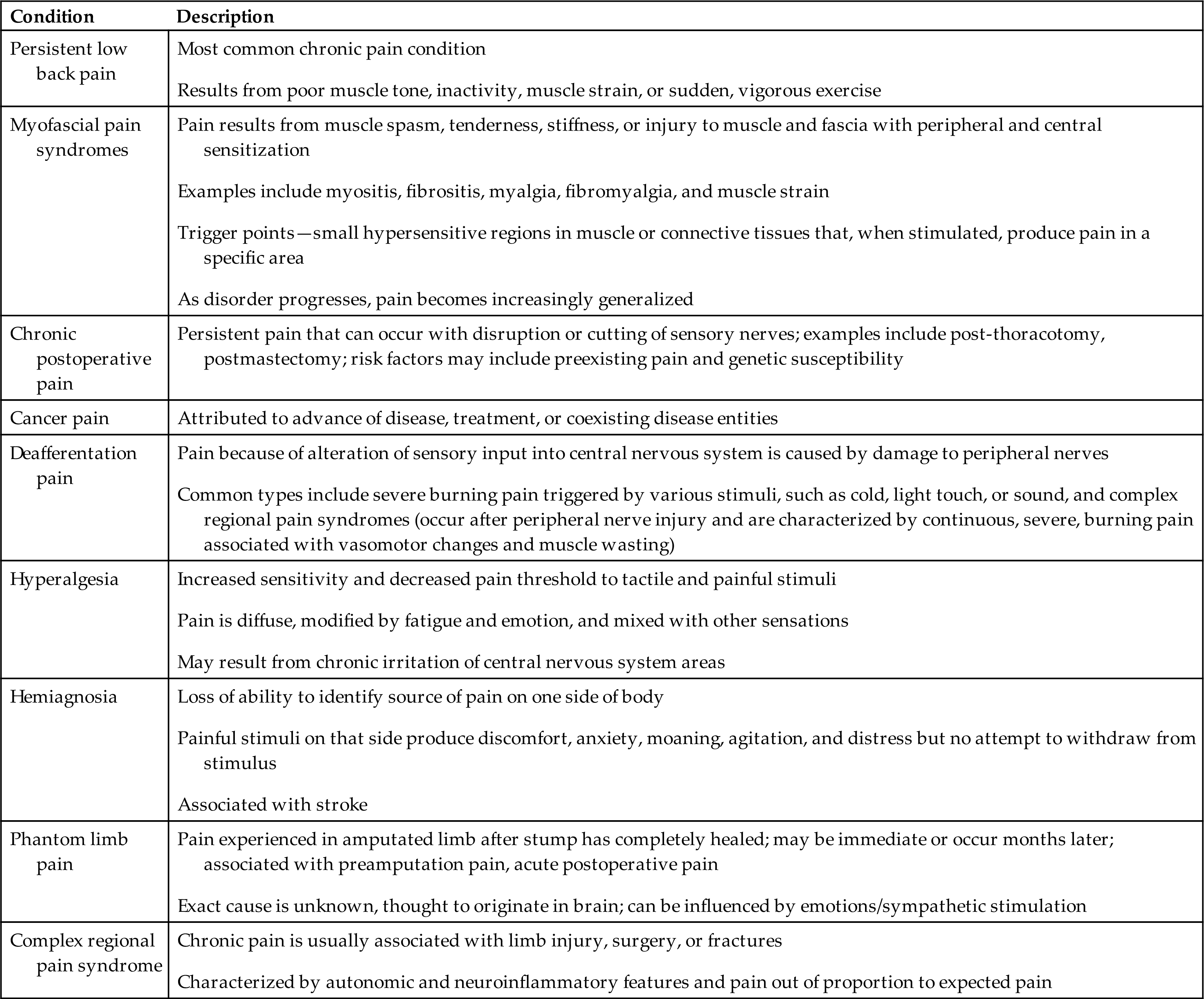

Table 16.4

Neuropathic pain is chronic pain initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the somatosensory nervous system and leads to long-term changes in pain pathway structures (neuroplasticity) and abnormal processing of sensory information. There is amplification of pain without stimulation by injury or inflammation. Neuropathic pain is often described as burning, shooting, shock-like, or tingling. It is characterized by increased sensitivity to painful or nonpainful stimuli with hyperalgesia, allodynia (the induction of pain by normally nonpainful stimuli), and the development of spontaneous pain.29 Neuropathic pain is classified as either peripheral or central and is associated with central and peripheral sensitization. Peripheral neuropathic pain is caused by peripheral nerve lesions. Peripheral sensitization is an increase in the sensitivity and excitability of primary sensory neurons and cells in the DRG. Examples include nerve entrapment, diabetic neuropathy, and chronic pancreatitis.

Central neuropathic pain is caused by a lesion or dysfunction in the brain or spinal cord. A progressive repeated stimulation of group C neurons (known as wind-up) in the dorsal horn leads to central sensitization, an increased sensitivity of central pain signaling neurons. This results in pathologic changes in the CNS that cause chronic pain. Examples include brain or spinal cord trauma, tumors, vascular lesions, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, postherpetic neuralgia, and phantom limb pain.

The following mechanisms have been implicated in the cause of neuropathic pain30:

- • Changes in sensitivity of neurons—lower threshold with peripheral and central sensitization

- • Spontaneous impulses from regenerating peripheral nerves

- • Alterations in the DRG and spinothalamic tract in response to peripheral nerve injury (i.e., deafferentation pain—loss of pain-related afferent information to the brain)

- • Loss of pain inhibition and stimulation of pain facilitation by excitatory neurotransmitters in the dorsal horn (e.g., release of glutamate)

- • Loss of descending inhibitory pain modulation

- • Hyperexcitable spinal interneurons stimulated by Aβ fibers (nonpainful stimulation of pain)

- • Release of nociceptive inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors by activated glial cells

- • Structural and functional alterations in brain processing neural networks

Because of the complexity of the causes of neuropathic pain syndromes, they are difficult to treat. Multimodal therapy is often needed, including nondrug treatment.31

An Overview of Chronic Pain Syndromes

Myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) is a regional pain syndrome associated with injury to muscle, fascia, and tendons and includes myositis, fibrositis, myofibrositis, myalgia, (see Chapter 44 for fibromyalgia), and muscle strain. MPS involves myofascial trigger points within a taut band of skeletal muscle (“muscle knots”). Compression of the trigger point causes a local twitch response (a small, quick contraction of muscle fibers) accompanied by referral of pain, motor dysfunction, and autonomic responses (e.g., flushing, diaphoresis, temperature changes). The symptoms often occur in association with poor muscle tone, inactivity, repeated muscle or tendon strain, sudden vigorous exercise, or muscle overuse. The pathophysiology is not clearly known. The pain may be the result of peripheral and central sensitization with low-threshold mechanosensitive afferents projecting to sensitized dorsal horn neurons. There may be neuroaxonal degeneration with alterations in neuromuscular transmission (e.g., extra leakage of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction induces persistent contraction) or muscle energy consumption that exceeds energy supply.32 During the early stages of the disorder the pain is localized, but as the disorder progresses, it becomes deep, aching, and more generalized. Chronic postoperative pain is pain that persists for at least 3 months after surgery, after ruling out any other possible causes, such as infection, tumor recurrence, or pain arising from pre-existing conditions. The types of pain can include nerve injury, complex regional pain syndrome, phantom limb pain, chronic donor site pain, post-thoracotomy pain syndrome, post-mastectomy pain syndrome, joint arthroplasty pain, and postsurgical abdominal and pelvic pain. Nerve injury and inflammation may induce plastic changes in the PNS and CNS contributing to peripheral and central nerve sensitization with allodynia and hypersensitivity. There may also be alterations in descending inhibitory pathways. Psychological factors, including anxiety and depression, also influence the occurrence of postoperative pain. Multimodal approaches to analgesia are needed for pain management including adequate management of preoperative pain and postoperative management of acute pain.33–35Cancer pain is often chronic, and the causes are multifactorial and related to site and type of cancer, extent of disease, treatment modalities, age, and access to care.36 Cancers generate and secrete mediators that sensitize and activate primary afferent nociceptors in the area of the tumor, resulting in neurochemical reorganization of the spinal cord, which contributes to spontaneous activity and enhanced pain responsiveness. Increasing pressure of a growing tumor on nerve endings, tissue destruction, inflammatory mediators, distention of visceral surfaces, obstruction of ducts and intestine, pathologic fractures, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, surgical procedures, and opioid-induced hyperalgesia also promote pain. These processes lead to both nociceptive and neuropathic pain.37 Therapeutic approaches to the management of cancer pain have advanced significantly in recent years, particularly in palliative care and hospice programs. Frequent assessment of pain, management of breakthrough pain, and implementation of individualized interdisciplinary therapeutic strategies (including pharmacotherapeutic, anesthetic, neurosurgical, psychologic, and rehabilitative techniques along with frequent evaluations) are essential to optimal cancer pain management. Research is in progress to evaluate the effects of different opioid receptors on tumor growth and suppression and will assist in selecting the optimum drugs for pain treatment.38Post-stroke pain syndromes can be acute but often occur up to 6 months after stroke and become chronic. Both nociceptive and neuropathic mechanisms of pain can be involved. Pain can include central poststroke pain or be secondary to spasticity, headache, shoulder pain, and complex region pain syndrome (see below). Central poststroke pain is pain and sensory abnormalities that manifest in the body parts that correspond to the area of the brain that have been injured by the cerebrovascular lesion. Hyperalgesia, dysesthesias, allodynia, spontaneous pain, and other sensory deficits are common.

There may be hyperexcitation in the damaged sensory pathways, damage to the central inhibitory pathways, or a combination of the two, making it difficult to differentiate from other causes of pain.39

Phantom limb pain (PLP) is pain that an individual feels in the amputated limb, usually distally (hands and feet) after the stump has completely healed (1 to 3 months after amputation). PLP is differentiated from residual limb pain, which is pain originating from the actual site of the amputated limb and can be associated with infection and neuroma formation. Both types of pain can occur at the same time. PLP can be intermittent or severe and occasional or constant, throbbing, stabbing, burning, or cramping. Both peripheral and central mechanisms of pain contribute to phantom limb pain. There is injury to peripheral nerves with increased excitability. Changes in pain processing in both the brain and spinal cord are known to occur.40 Nonpainful phantom limb sensations occur in almost all amputees, but the sensations usually fade with time. Chronic regional pain syndrome type II can also be a component of PLP.

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is chronic neuropathic pain usually associated with limb injury. Two forms are described: complex regional pain syndrome-I (CRPS-I) (previously termed reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome) associated with injury but no apparent nerve injury; and complex regional pain syndrome-II (CRPS-II) (previously termed causalgia) with evidence of nerve injury. The symptoms of both forms are similar. CRPS is distinguished from other chronic pain disorders by signs of autonomic and inflammatory changes in the pain region of the injured nerve. There are autonomic symptoms: changes in skin color, temperature, and sweating and alterations in hair and nail growth for the affected limb; motor symptoms: tremor or weakness may be present; and sensory symptoms: hypersensitivity, hyperalgesia, and allodynia. CRPS is further distinguished as “warm CRPS,” associated with a warm, red, and edematous extremity; and “cold CRPS,” associated with a cold, dusky, and sweaty extremity. Peripheral and central sensitization contribute to the pain syndrome, but the mechanisms are unknown. A combination of injury and the presence of inflammatory cytokines and neuropeptides may lead to peripheral nociceptive sensitization and physiologic change in pain transmission and in autonomic and motor systems.41

Temperature Regulation

Human thermoregulation is achieved through precise balancing of heat production, heat conservation, and heat loss The normal range of body temperature is considered to be 36.2°C to 37.7°C (96.2°F to 99.4°F) overall, but a person's individual body parts will vary in temperature. Body temperature rarely exceeds 41°C (105.8°F). The extremities are generally cooler than the trunk, and the temperature at the core of the body (as measured by rectal temperature) is generally 0.5°C higher than the surface temperature (as measured by oral temperature). Internal temperature varies in response to activity, environmental temperature, and daily fluctuation (circadian rhythm). Oral temperatures fluctuate within 0.2°C to 0.5°C during a 24-hour period. Women tend to have wider fluctuations that follow the menstrual cycle, with a sharp rise in temperature just before ovulation. The daily fluctuating temperature in both sexes peaks around 6 p.m. and is at its lowest during sleep. Maintenance of body temperature within the normal range is necessary for life.

Control of Body Temperature

Temperature regulation (thermoregulation) is mediated primarily by the hypothalamus and endocrine system. Peripheral thermoreceptors in the skin, liver, and skeletal muscle (unmyelinated C fibers and thinly myelinatewd Aδ fibers) and central thermoreceptors in the hypothalamus, spinal cord, viscera, and great veins provide the hypothalamus with information about body temperatures. If these temperatures are low or high, the hypothalamus triggers heat production and heat conservation or heat loss mechanisms.42

Body heat is produced by the chemical reactions of metabolism and skeletal muscle tone and contraction. The heat-producing mechanism (chemical or non-shivering thermogenesis) begins with hypothalamic thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH); it stimulates the anterior pituitary to release thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which acts on the thyroid gland and stimulates the release of thyroxine. Thyroxine then acts on the adrenal medulla, causing the release of epinephrine into the bloodstream. Epinephrine causes cutaneous vasoconstriction, stimulates glycolysis, and increases metabolic rate, thus increasing body heat. Norepinephrine and thyroxine activate brown fat thermogenesis where energy is released as heat (non-shivering thermogenesis) instead of as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Heat is distributed by the circulatory system.

The hypothalamus also triggers heat conservation by stimulating the sympathetic nervous system and results in increased skeletal muscle tone, initiating the shivering response and producing vasoconstriction. Sympathetic stimulation also constricts peripheral blood vessels and redistributes blood flow. Centrally warmed blood is shunted away from the periphery to the core of the body, where heat can be retained. This involuntary mechanism takes advantage of the insulating layers of the skin and subcutaneous fat to protect the core temperature. The hypothalamus relays information to the cerebral cortex about cold, and voluntary responses result. Individuals typically bundle up, keep moving, or curl up in a ball. These types of voluntary physical activities provide insulation, increase skeletal muscle activity, and decrease the amount of skin surface available for heat loss through radiation, convection, and conduction.

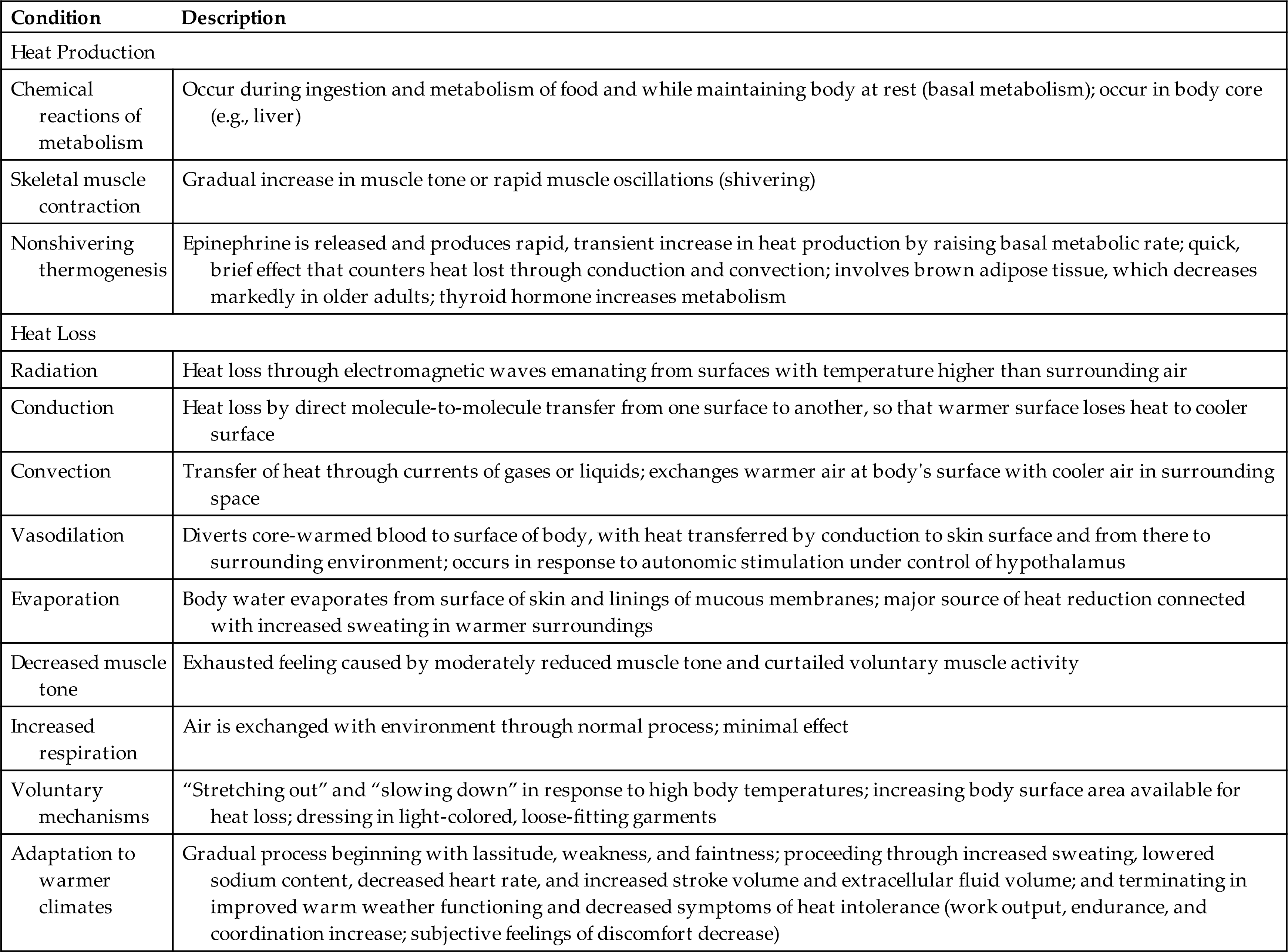

The hypothalamus responds to warmer core and peripheral temperatures by reversing the same mechanisms resulting in heat loss. Heat loss is achieved through (1) radiation, (2) conduction, (3) convection, (4) vasodilation, (5) evaporation (sweating), (6) decreased muscle tone, (7) increased respiration, (8) voluntary measures, and (9) adaptation to warmer climates (i.e., increasing or decreasing the volume of sweat). Table 16.5 summarizes further information about heat production and loss.

Table 16.5

Temperature Regulation in Infants and Older Adult Persons

Infants (particularly low-birth-weight infants) and older adult persons require special attention to maintenance of body temperature. Term infants produce sufficient body heat, primarily through metabolism of brown fat, but cannot conserve heat produced because of their small body size, greater ratio of body surface to body weight, and inability to shiver. Infants also have little subcutaneous fat and thus are not as well insulated as adults. Children also have a greater ratio of body surface to body weight, lower sweating rate, higher peripheral blood flow in the heat, and a greater extent of vasoconstriction in the cold than adults. They can acclimatize to changes in environmental temperatures but do so at a lower rate than adults.

Older adult persons respond poorly to environmental temperature extremes because of their slowed blood circulation, structural and functional skin changes, overall decreased heat-producing activities, and the presence of disease (i.e., congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, diabetes mellitus, or peripheral vascular disease). Cold stress in older adults also decreases coronary perfusion.43 In addition, older adult persons have a decreased shivering response (delayed onset and decreased effectiveness), slowed metabolic rate, decreased vasoconstrictor response, diminished or absent ability to sweat, decreased peripheral sensation, desynchronized circadian rhythm, decreased perception of heat and cold, decreased thirst, decreased nutritional reserves, decreased brown adipose tissue, and decreased shivering response.44,45

Pathogenesis of Fever

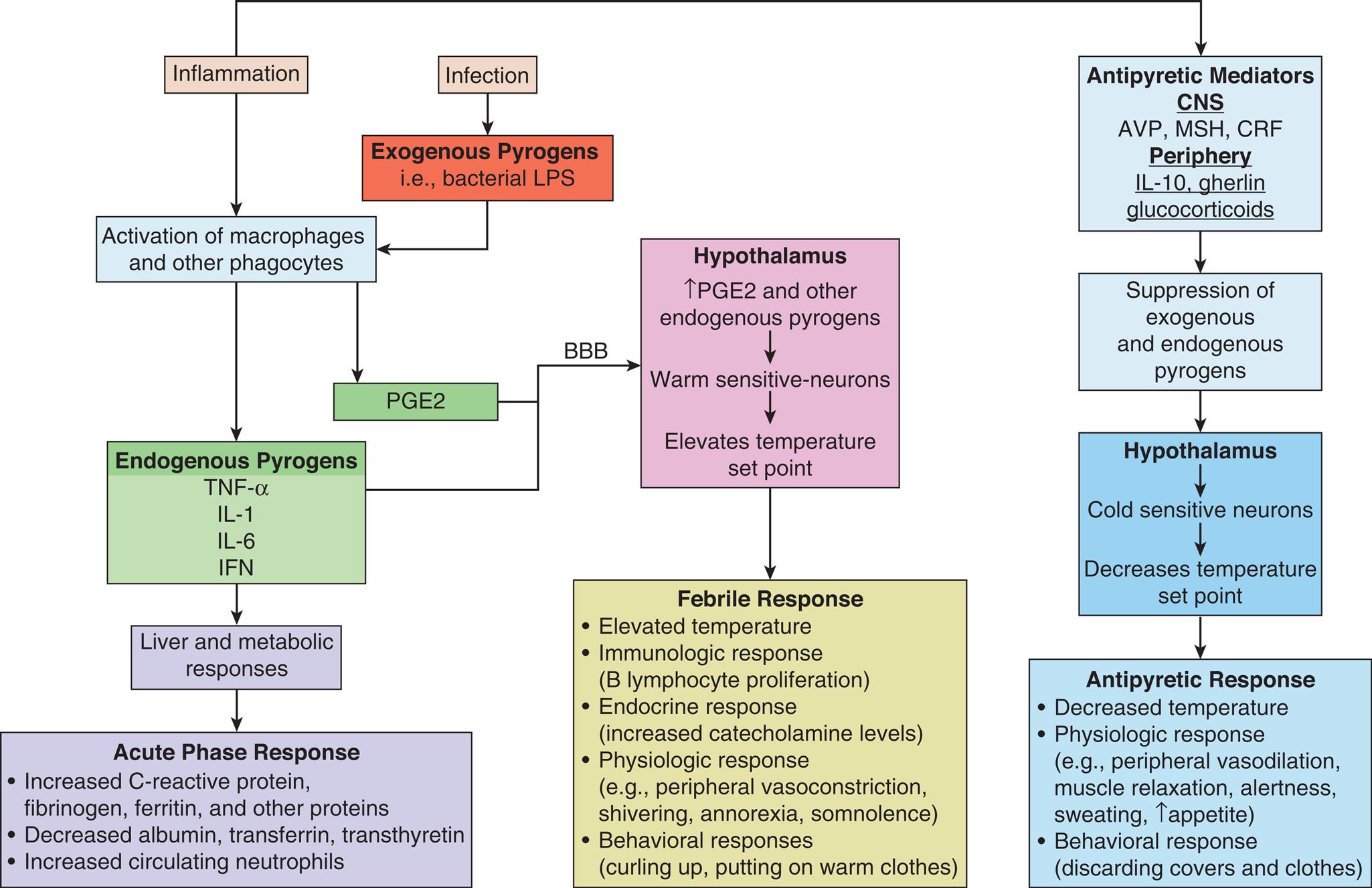

Fever (febrile response) is a temporary resetting of the hypothalamic thermostat to a higher level in response to exogenous or endogenous pyrogens. Exogenous pyrogens (endotoxins produced by pathogens; see Chapter 10) stimulate the release of inflammatory endogenous pyrogens from phagocytic cells (primarily macrophages), including Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interferon γ (IFNγ). These pyrogenic cytokines raise the thermal set point by acting on the hypothalamus to induce an integrated endocrine, autonomic nervous system, and behavioral response and also initiate the acute phase response (described below). The hypothalamic set point for temperature regulation is elevated, signaling an increase in heat production and conservation. Peripheral vasoconstriction shunts blood from the skin to the body core. Epinephrine release increases metabolic rate and muscle tone. Decreased release of vasopressin (anti-diuretic hormone) reduces the volume of body fluid to be heated. The individual feels colder, dresses more warmly, decreases body surface area by curling up, and may go to bed in an effort to get warm. Symptoms of lassitude and anorexia are common and may be related to energy conservation to support the increased metabolic demands of fever. Body temperature is maintained at the new level until the fever “breaks,” when the set point begins to return to normal with decreased heat production and increased heat reduction mechanisms. The individual feels very warm, dons cooler clothes, throws off the covers, and stretches out. Once the body has returned to a normal temperature, the individual feels more comfortable and the hypothalamus adjusts thermoregulatory mechanisms to maintain the new temperature (Fig. 16.6).

Infection and inflammation initiate the release of exogenous pyrogens from pathogens and endogenous pyrogens from macrophages and other immune cells. Endogenous pyrogens and PGE2 act on the hypothalamus to elevate the temperature set point and initiate fever and the acute phase response. Fever is modulated by antipyretic mediators (cryogens) from both the CNS and periphery which suppress the febrile response and prevent damage from excessively high temperatures. BBB, Blood brain barrier; AVP, arginine vasopressin; CRP, C-reactive protein; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin-1, interleukin-6; MCH, melanocortin; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

A flow chart represents the pathogenesis of fever and the acute phase response. • The inflammation initiates the activation of macrophages and other phagocytes from endogenous pyrogens such as T N F alpha, I L 1, I L 8, I F N and antipyretic mediators such as A V P, M S H, C R F in C NS and I L 10, ghrelin, glucocorticoids in the periphery leads to suppression of exogenous and endogenous pyrogens that acts on hypothalamus involves in cold-sensitive neurons and decreases temperature set point leading to an antipyretic response. • The inflammation that initiates endogenous pyrogens acts on liver and metabolic responses leads to acute phase response. • The infection initiates the exogenous pyrogens that are bacterial L P S from the activation of macrophages and other phagocytes and P G E 2 which acts on the hypothalamus and increases the P G E G and other endogenous pyrogens, warm-sensitive neurons and elevate temperature set point leading to a febrile response. • The acute phase response initiates an increase in C reactive protein, fibrinogen, ferritin, and other proteins; decreases albumin, transferrin, transthyretin; increases circulating neutrophils. • Febrile response initiates elevated temperature; immunologic response (B lymphocyte proliferation); endocrine response (increased catecholamine levels); physiologic response for example peripheral vasoconstriction, shivering, anorexia, somnolence; behavioral responses (curling up, putting on warm clothes). • Antipyretic responses initiate decreased temperature; physiologic responses for example peripheral vasodilation, muscle relaxation, alertness, sweating, and increase appetite; behavioral response (discarding covers and clothes).

An acute phase response (see Chapter 7) is a defensive reaction to control pathogens that occurs when pyrogenic and other cytokines are released in response to infection and inflammation. Protective proteins such as C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and ferritin are produced. Other proteins such as albumin, transferrin, and transthyretin are reduced. Neutrophils numbers are increased. In addition to fever, other symptoms occur, including anorexia, fatigue, malaise, somnolence, and loss of concentration. At the cellular level, inflammatory pyrogenic cytokines promote muscle catabolism and hyperglycemia (gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, and insulin resistance) by stimulating release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and glucocorticoids to support glucose-consuming cells.46

During inflammation and fever, cryogens modulate the duration and intensity of the febrile response. Antipyretic cytokines such as arginine vasopressin (AVP), melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH), and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) are released from the brain, and systemic anti-inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-10, ghrelin, glucocorticoids) are released from the periphery. These mediators act as endogenous cryogens or antipyretics to decrease the thermal set point in the hypothalamus (see Fig. 16.6).47 This antipyretic effect constitutes a negative-feedback loop for temperature control and prevents lethal effects of uncontrolled temperature elevation. When this antipyretic effect is ineffective or the physiologic response to fever is dangerous to organ system function, antipyretic medications (e.g., aspirin, acetaminophen, or ibuprofen) may be given to suppress PGE2 and fever.

Febrile seizures may occur in children with temperatures greater than 38°C (100.4°F) without CNS infection, hypoglycemia, or electrolyte disorders. The seizures are caused by systemic infection with the release of inflammatory cytokines that cross the blood-brain barrier and stimulate neuronal hyperexcitability, triggering the seizure.48 Febrile seizures are more predominant in boys before age 5 years, and genetic factors contribute to susceptibility. Simple febrile seizures are generally brief and self-limiting, lasting less than 5 minutes and without recurrence. Complex febrile seizures last more than 15 minutes with focal neurologic signs (e.g., one side of body involved, stiff neck) and recur within 24 hours. Although in most instances there appear to be no long-term effects on the child, a small percentage of children may develop epilepsy.49 Prolonged febrile seizures are associated with the development of temporal lobe epilepsy in children and are probably associated with functional changes in neurons and neural networks. Treatment includes antipyretic and/or antiepileptic drugs.50

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) is a body temperature of greater than 38.3°C (101°F) for longer than 3 weeks’ duration that remains undiagnosed after 3 days of hospital investigation, three outpatient visits, or 1 week of ambulatory investigation. The clinical categories of FUO include infectious, rheumatic/inflammatory, neoplastic, HIV-associated, and miscellaneous and undiagnosed disorders.51

Benefits of Fever

Moderate fever helps the body respond to infectious processes through several mechanisms.52,53

- 1. Raising of body temperature kills many pathogens and adversely affects their growth and replication.

- 2. Higher body temperatures decrease serum levels of iron, zinc, and copper—minerals needed for bacterial replication.

- 3. Increased temperature causes lysosomal breakdown and autodestruction of cells, preventing viral replication in infected cells.

- 4. Heat increases lymphocytic transformation and motility of polymorphonuclear neutrophils, facilitating the immune response.

- 5. Phagocytosis is enhanced, and production of antiviral interferon is augmented.

Suppression of fever with antipyrogenic medications can be effective but should be used with caution.54

Infection and fever responses in older adult persons and children may vary from those in normal adults. Box 16.2 lists the principal features associated with fever at these extremes of age.45,55

Disorders of Temperature Regulation

Hyperthermia

Hyperthermia is elevation of the body temperature without an increase in the hypothalamic set point. Hyperthermia can produce nerve damage, coagulation of cell proteins, and death. At 41°C (105.8°F), nerve damage produces convulsions in the adult. Death results at 43°C (109.4°F). Hyperthermia may be therapeutic, accidental, or associated with stroke or head trauma. Prevention of hyperthermia in stroke and head trauma assists in limiting brain injury.56

Therapeutic hyperthermia is a form of local, regional, or whole-body hyperthermia used to destroy pathologic microorganisms or tumor cells by facilitating the host's natural immune process or tumor blood flow or activate drugs.57,58

The forms of accidental hyperthermia are summarized as follows.59

- 1. Heat cramps—severe, spasmodic cramps in the abdomen and extremities that follow prolonged sweating and associated sodium loss. Usually occur in those not accustomed to heat or those performing strenuous work in very warm climates. Fever, rapid pulse rate, and increased blood pressure accompany the cramps. Treatment includes administration of oral dilute salt solutions.

- 2. Heat exhaustion—results from prolonged high core or environmental temperatures that cause profound vasodilation and profuse sweating, leading to dehydration, decreased plasma volumes, hypotension, decreased cardiac output, and tachycardia. Symptoms include weakness, dizziness, confusion, nausea, and fainting. Treatment includes administration of oral or parenteral dilute salt solution.

- 3. Heat stroke—a potentially lethal condition associated with multiorgan failure. Heat stroke can be caused by exertion, by overexposure to environmental heat, or from impaired physiologic mechanisms for heat loss. With very high core temperatures (>40°C [104°F]), there is cell injury and loss of body heat regulation. Symptoms include high core temperature, absence of sweating, rapid pulse rate, confusion, agitation, and coma. The increase in skin blood flow requirements decreases intestinal blood flow and increases intestinal membrane permeability. Increased circulating endotoxin, release of inflammatory mediators, and hypovolemia promote coagulation with microvascular thrombosis leading to multiorgan system and neuronal dysfunction. Complications include cerebral edema, degeneration of the CNS, swollen dendrites, renal tubular necrosis, and hepatic failure with delirium, coma, and eventually death if treatment is not undertaken. There is controversy about whether there is failure of the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center during the acute phase of recovery.60,61

- 4. Malignant hyperthermia—a potentially lethal hypermetabolic complication of a rare autosomal dominant inherited muscle disorder that may be triggered by inhaled halogenated anesthetics and depolarizing muscle relaxants.62 The syndrome involves uncontrolled release of calcium from muscle cells with hypermetabolism, uncoordinated muscle contractions, increased muscle work, increased oxygen consumption, hypercarbia, and a raised level of lactic acid production. Acidosis develops, and body temperature rises, with resulting tachypnea, tachycardia, cardiac dysrhythmias, hypotension, decreased cardiac output, and cardiac arrest. Signs resemble those of coma—unconsciousness, absent reflexes, fixed pupils, apnea, and occasionally a flat electroencephalogram. Oliguria and anuria are common. It is most common in children and adolescents. Treatment includes withdrawal of the provoking agent, oxygen therapy, body cooling therapy, administration of drugs that inhibit calcium release from muscle (dantrolene), treatment of arrhythmias, and maintenance of urine output.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia (core body temperature less than 35°C [95°F]) produces depression of the CNS and respiratory system, vasoconstriction, alterations in microcirculation and coagulation, and ischemic tissue damage. Hypothermia may be accidental or therapeutic (Box 16.3). Most tissues can tolerate low temperatures in controlled situations, such as surgery. However, in severe hypothermia, ice crystals form on the inside of the cell, causing cells to rupture and die. Tissue hypothermia slows cell metabolism, increases the blood viscosity, slows microcirculatory blood flow, facilitates blood coagulation, and stimulates profound vasoconstriction (also see Frostbite, Chapter 46).

Trauma and Temperature

Major body trauma can affect temperature regulation through various mechanisms. Damage to the CNS, release of inflammatory mediators, increased intracranial pressure, or intracranial bleeding typically produces a body temperature of greater than 39°C (102.2°F), generally higher than infectious fever. This sustained noninfectious fever, often referred to as a central fever or neurogenic fever, appears with or without bradycardia. A central fever does not induce sweating and is very resistant to antipyretic therapy.63 Other traumatic mechanisms that produce temperature alterations include accidental injuries, hemorrhagic shock, major surgery, and thermal burns. The severity and type of alteration (hyperthermia or hypothermia) vary with the severity of the cause and the body system affected.

Accidental Hypothermia Accidental hypothermia is generally the result of sudden immersion in cold water or prolonged exposure to cold environments. At particular risk for accidental hypothermia are infants and older adults, because thermoregulatory mechanisms are immature or altered in these two groups. Also at risk are individuals with conditions that diminish the ability to generate heat. Such conditions include hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, decreased liver function, malnutrition, Parkinson disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. Other risk factors include chronic increased vasodilation and decreased thermoregulatory control caused by cerebral injuries, ketoacidosis, uremia, and drug overdoses. In acute hypothermia, peripheral vasoconstriction shunts blood away from the cooler skin to the core in an effort to decrease heat loss, which produces peripheral tissue ischemia. Intermittent reperfusion of the extremities (the Lewis phenomenon) helps preserve peripheral oxygenation. Intermittent peripheral perfusion continues until core temperatures drop dramatically.The hypothalamic center stimulates shivering in an effort to increase heat production. Severe shivering occurs at core temperatures of 35°C (95°F) and continues until core temperature (measure by esophageal probe) drops to about 30° to 32°C (86° to 89.6°F). Prolonged shivering can lead to exhaustion of liver glycogen stores. Thinking becomes sluggish and coordination is decreased at 34°C (93.2°F). As hypothermia deepens, paradoxical undressing may occur as hypothalamic control of vasoconstriction is lost and vasodilation occurs with loss of core heat to the periphery. The hypothermic individual therefore feels suddenly warm and begins to remove clothing.At 30°C (86°F), the individual becomes stuporous, heart rate and respiratory rate decline, and cardiac output is diminished. Cerebral blood flow is decreased. Metabolic rate declines, further decreasing core temperature. Sinus node depression occurs with slowing of conduction through the atrioventricular node. In severe hypothermia (core temperature of 26° to 28°C [78.8° to 82.4°F]), pulse and respirations may be undetectable and require resuscitation. Acidosis is moderate to severe. Coagulopathy, ventricular fibrillation, and asystole are common.117 Surface cooling may cause frostbite and fat necrosis.If hypothermia is mild, passive rewarming may be sufficient. If core temperature is greater than 30°C (86°F), active rewarming also may be required. Active rewarming uses warm-water baths, warm blankets, heating pads, and warm oral fluids when the individual is fully alert. Core rewarming may be accomplished through administration of warm intravenous (IV) solutions, warm gastric lavage, warm peritoneal lavage, inhalation of warmed gases, and, in extreme cases, exchange transfusions, warming blood in a pump oxygenator circuit, and mediastinal lavage.Rewarming generally should proceed no faster than a few degrees per hour. Short-term complications of rewarming include acidosis, rewarming shock, and dysrhythmias. Long-term complications include congestive heart failure, hepatic and renal failure, abnormal erythropoiesis, myocardial infarction, pancreatitis, and neurologic dysfunctions.

Therapeutic Hypothermia Therapeutic hypothermia is used to slow metabolism and preserve ischemic tissue after brain trauma or during brain surgery, after cardiac arrest, and in neonatal hypoxic encephalopathy. Hypothermia protects the brain by reduction in metabolic rate, ATP consumption, oxidative stress, and the critical threshold for oxygen delivery; modulation of excitotoxic neurotransmitters and calcium antagonism; preservation of protein synthesis and the blood-brain barrier; decreased edema formation; and modulation of the inflammatory response.

Sleep

Sleep is an active multiphase process that provides restorative functions and promotes memory consolidation. Complex neural circuits, interacting hormones, and neurotransmitters involving the hypothalamus, thalamus, brainstem, and cortex control the timing of the sleep-wake cycle and coordinate this cycle with circadian rhythms (24-hour rhythm cycles).64 Normal sleep has two primary phases that can be documented by electroencephalogram (EEG), a test that detects electrical activity in your brain: rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (20% to 25% of sleep time) and slow-wave (non-REM) sleep. Non-REM sleep is further divided into three stages (N1, N2, N3) from light to deep sleep. REM cycles do not typically start to occur until about 90 minutes into sleep. Four to six cycles of REM and non-REM sleep occur each night in an adult. Sleep duration and sleep architecture do not mature in children until after adolescence.65 The hypothalamus is a major sleep center, and the hypocretins (orexins), acetylcholine, and glutamate are neuropeptides secreted by the hypothalamus that promote wakefulness. Prostaglandin D2, adenosine, melatonin, serotonin, L-tryptophan, GABA, and growth factors promote sleep. The pontine reticular formation is primarily responsible for generating REM sleep, and projections from the thalamocortical network produce non-REM sleep.66

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is initiated by REM-on and REM-off neurons in the pons and mesencephalon. REM sleep occurs about every 90 minutes beginning 1 to 2 hours after non-REM sleep begins. This sleep is known as paradoxical sleep because the EEG pattern is similar to that of the normal awake pattern and the brain is very active with dreaming. REM and non-REM sleep alternate throughout the night, with lengthening intervals of REM sleep and fewer intervals of deeper stages of non-REM sleep toward morning. The changes associated with REM sleep include increased parasympathetic activity and variable sympathetic activity associated with rapid eye movement; muscle relaxation; loss of temperature regulation; altered heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration; penile erection in men and clitoral engorgement in women; release of steroids; and many memorable and often bizarre dreams. Respiratory control appears largely independent of metabolic requirements and oxygen variation. Loss of normal voluntary muscle control in the tongue and upper pharynx may produce respiratory obstruction which, in turn, can precipitate apneic events. Cerebral blood flow increases.

Non-REM sleep accounts for 75% to 80% of sleep time in adults and is initiated when inhibitory signals are released from the hypothalamus. Sympathetic tone is decreased and parasympathetic activity is increased during non-REM sleep, creating a state of reduced activity. The basal metabolic rate falls by 10% to 15%; temperature decreases 0.5°C to 1°C (0.9°F to 1.8°F); heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, and muscle tone decrease; and knee jerk reflexes are absent. Pupils are constricted. During the various stages, cerebral blood flow to the brain decreases and growth hormone is released, with corticosteroid and catecholamine levels depressed. Non-REM sleep is associated with memory consolidation during slow wave sleep.67Box 16.4 summarizes sleep characteristics in infants, children, and older adult persons.

Sleep Disorders

Because classification of sleep disorders is complex, a system has been established by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and includes seven major categories: (1) insomnia, (2) sleep-related breathing disorders, (3) central disorders of hypersomnolence, (4) circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders, (5) parasomnias, (6) sleep-related movement disorders, and (7) other sleep disorders.68 The most common disorders are summarized here.

Common Dyssomnias

Insomnia is the inability to fall or stay asleep; it is accompanied by fatigue, malaise, and difficulty with performance during wakefulness and may be mild, moderate, or severe. It may be transient, lasting a few days or months (primary insomnia), and related to travel across time zones or caused by acute stress, or very commonly inadequate “sleep hygiene.” Sleep hygiene simply refers to behavioral and environmental practices that are intended to promote better-quality sleep (e.g., avoiding all-nighters and caffeine late in the evening). Chronic insomnia lasts at least 3 months and can be idiopathic, start at an early age, and be associated with drug or alcohol abuse, chronic pain disorders, chronic depression, the use of certain drugs, obesity, aging, genetics, and environmental factors that result in hyperarousal.69

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is the most commonly diagnosed sleep disorder and occurs in all age groups. However, the incidence of OSAS increases with age beyond 60 years. Major risk factors include obesity, male sex, older age, and postmenopausal status (not on hormone therapy) in women, craniofacial anomalies, and increased size of tonsillar and adenoid tissue.70 OSAS results from partial or total upper airway obstruction to airflow recurring during sleep with continuous respiratory efforts made against a closed airway. It is often accompanied by excessive loud snoring, gasping, and multiple apneic episodes that last 10 seconds or longer. Central sleep apnea is the temporary absence or diminution of ventilatory effort during sleep with decreased sensitivity to carbon dioxide and oxygen tensions, and decreased airway dilator muscle activation. It may be associated with heart failure, neurologic disease, high altitude, or narcotic medications. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome is a combination of obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg·m-2), daytime hypercapnia (arterial carbon dioxide tension ≥ 45 mmHg), and sleep disordered breathing not caused by other disorders of hypoventilation. It may be related to leptin resistance because leptin also is a strong respiratory stimulant. The periodic breathing eventually produces arousal, which interrupts the sleep cycle, reducing total sleep time and producing sleep and REM deprivation. Sleep apnea produces hypercapnia and low oxygen saturation and if left untreated, eventually leads to polycythemia, pulmonary hypertension, systemic hypertension, stroke, right-sided congestive heart failure, dysrhythmias, liver congestion, cyanosis, and peripheral edema.

Hypersomnia (excessive daytime sleepiness) is associated with OSAS. Individuals may fall asleep while driving a car, working, or even while conversing, with significant safety concerns.71 Sleep deprivation also can result in impaired mood and cognitive function characterized by impairments of attention, episodic memory, working memory, and executive functions (i.e., decision-making ability).

Polysomnography and home sleep testing are used to diagnose OSAS, in addition to the history and physical examination. Treatments include use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and dental devices, surgery of the upper airway, hypoglossal nerve stimulation in selected individuals, and management of obesity.72 Adenotonsillar hypertrophy is the major cause of obstructive sleep apnea in children, and obesity increases the risk. Tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy is the treatment of choice.73

Narcolepsy is a primary hypersomnia with disruption in REM sleep-wake cycles characterized by hallucinations, sleep paralysis, excessive daytime sleepiness, and, rarely, cataplexy (brief spells of muscle weakness). Narcolepsy is usually sporadic or can occur in families. Type I narcolepsy (narcolepsy with cataplexy) is associated with immune-mediated T-cell destruction of hypocretin (orexin)-secreting cells in the hypothalamus. Orexins stimulate wakefulness. Type II narcolepsy (narcolepsy without cataplexy) is less severe and associated with normal levels of orexins (hypocretins). The cause is unknown.74

Circadian rhythm sleep disorders are common disorders of the 24-hour sleep-wake schedule with disruption in the timing of sleep. They involve difficulty falling asleep, waking up during the sleep cycle, or waking up too early and being unable to fall back to sleep. These disorders can result from extrinsic causes, such as rapid time zone changes (or jet-lag syndrome), alternating the sleep schedule (rotating work shifts) involving 3 hours or more in sleep time, or changing the total sleep time from day to day. Common types of these disorders include advanced sleep phase disorder (early evening sleeping, e.g., 6:00 pm and early morning waking, e.g., 3:00 to 5:00 am), or delayed sleep phase disorder (late night sleeping, e.g., at 2:00 am and late morning or afternoon waking). A circadian rhythm sleep disorder known as shift work sleep disorder affects many shift workers who rotate or swing long shifts (such as nurses), particularly between the hours of 2200 (10 PM) and 0600 (6 AM). Jet lag disorder is a disturbance in the circadian rhythm from crossing time zones more rapidly than the circadian system can keep pace. Eastward travel is more difficult than westward travel because it is easier to delay sleep than to advance sleep.

The disruption of circadian rhythms may cause problems in the short term, such as cognitive deficits, poor vigilance, difficulty concentrating, and inadequate performance of psychomotor tasks. However, long-term health consequences of shift work sleep disorder may be quite serious and include depression/anxiety, increased risk for cardiovascular disease, and increased all-cause mortality. Sleep cycle phenotype also has a genetic basis and influences the timing and cycles of sleep and can affect advances or delays in sleep-wake times (see Emerging Science Box: Shift Work Disorder).75

Common Parasomnias

Parasomnias are unusual behaviors occurring during non-REM stage 3 (slow-wave) sleep (disorders of arousal) and REM-related sleep behavior disorder.76 Non-REM sleep behaviors are associated with an inability to maintain deep sleep and an increased number of arousals. Behaviors include sleepwalking, having night terrors, rearranging furniture, eating food, exhibiting sleep sex or violent behavior, and having restless leg syndrome. REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is manifested by loss of REM paralysis, leading to potentially injurious dream enactment. Nonmotor symptoms are nonspecific and include olfactory dysfunction, abnormal color vision, autonomic dysfunction, excessive daytime sleepiness, depression, and cognitive impairment. RBD is a common prodromal non-motor manifestation of Parkinson disease.77

Two dysfunctions of sleep (somnambulism and night terrors) are common in children and may be related to CNS immaturity. Somnambulism (sleepwalking) is a non-REM parasomnia disorder primarily of childhood and appears to resolve within a few years. Sleepwalking is therefore not associated with dreaming, and the child has no memory of the event on awakening. Sleepwalking in adults is often associated with sleep-disordered breathing. Night terrors are characterized by sudden apparent arousals in which the child expresses intense fear or emotion. However, the child is not awake and can be difficult to arouse. Once awakened, the child has no memory of the night terror event. Night terrors are not associated with dreams. Although this problem occurs most often in children, adults also may experience it with corresponding daytime anxiety.

Restless Leg Syndrome

Restless legs syndrome (RLS)/Willis Ekbom disease is a common sensorimotor disorder associated with unpleasant sensations (prickling, tingling, crawling) and nonvolitional periodic leg movements that occurs at rest and is worse in the evening or at night. There is a compelling urge to move the legs for relief, with a significant effect on sleep and quality of life. The disorder is more common in women, during pregnancy, in older adults, and in individuals with iron deficiency. RLS has a familial tendency, although no monogenetic cause has been found. RLS is associated with a circadian fluctuation of dopamine in the substantia nigra. Iron is a cofactor in dopamine production, and some individuals respond to iron administration as well as low-dose dopamine agonists. Diagnostic and treatment guidelines have been established to assist with disease management.78

The Special Senses

Vision

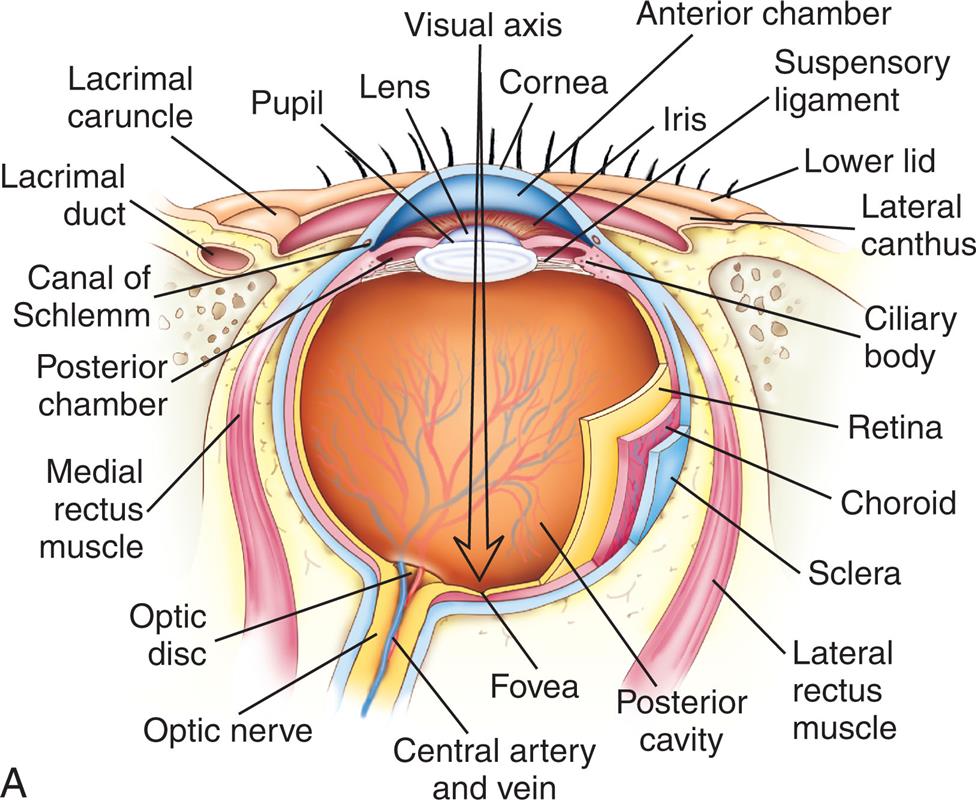

The eyes are complex sense organs responsible for vision. Within a protective casing, each eye has receptors, a lens system for focusing light on the receptors, and a system of nerves for conducting impulses from the receptors to the brain. Visual dysfunction may be caused by abnormal ocular movements or alterations in visual acuity, refraction, color vision, or accommodation. Visual dysfunction also may be the secondary effect of another neurologic disorder.

The Eye

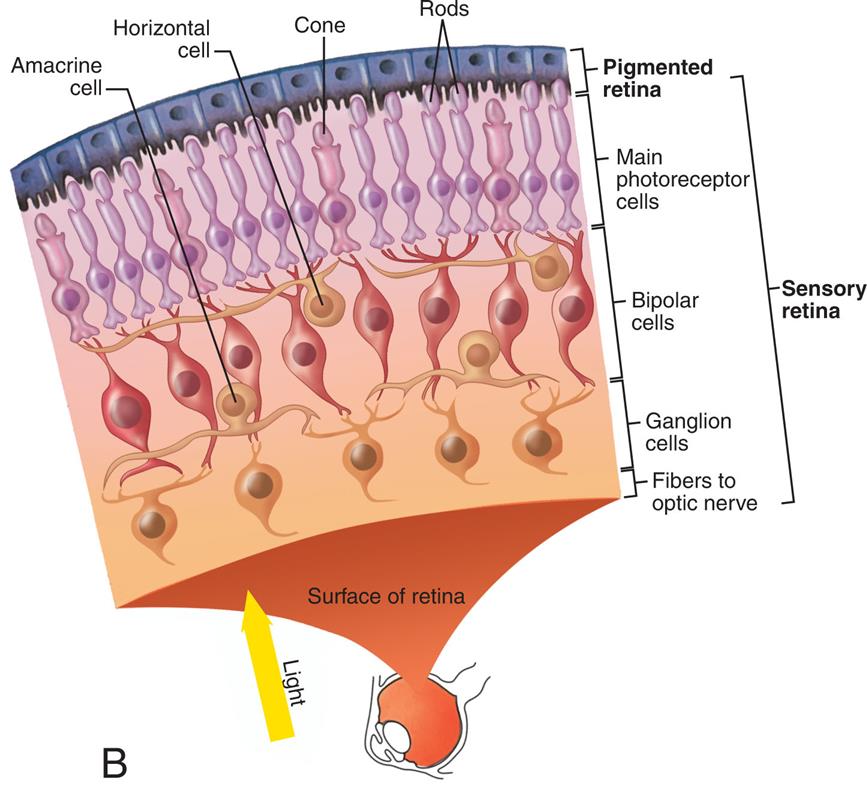

The wall of the eye consists of three layers: (1) sclera, (2) choroid, and (3) retina (Fig. 16.7). The sclera is the thick, white, outermost layer. It becomes transparent at the cornea—the portion of the sclera in the central anterior region that allows light to enter the eye. The choroid is the deeply pigmented middle layer that prevents light from scattering inside the eye. The iris, part of the choroid, has a round opening, the pupil, through which light passes. Smooth muscle fibers control the size of the pupil so that it adjusts to bright light or dim light and to close or distant vision.