Alterations in Cognitive Systems, Cerebral Hemodynamics, and Motor Function

Kaveri Roy and Sue E. Huether

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Rogers/pathophysiology/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Rogers/pathophysiology/

Intellectual and behavioral functions are achieved by integrated processes of cognitive systems, sensory systems, and motor systems. The purpose of this chapter is to present the concepts and processes of these alterations as an approach to understanding the manifestation of neurologic dysfunction that can occur with disease or injury. Some specific diseases are also presented in this chapter (Parkinson disease [PD], Huntington disease [HD], and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [ALS]) because they fit best here. The manifestations for specific central and peripheral nervous system disorders are presented in Chapter 18 (brain and spinal cord injury, stroke, seizure, and headache syndromes). Alterations in sensory function and sleep were presented in Chapter 16 (pain, temperature regulation, sleep, and the special senses—vision, hearing, touch, and proprioception).

The neural systems are structures that build, support, facilitate, and organize sensorimotor input and output.1 The neural systems essential to cognitive function are (1) attentional systems that provide arousal and maintenance of attention over time, (2) memory and language systems by which information is communicated, and (3) affective or emotive systems that mediate mood, emotion, and intention. These core systems are fundamental to the processes of abstract thinking and reasoning. The products of abstraction and reasoning are organized and made operational through the executive attentional networks. The normal functioning of these systems manifests through the motor system in a behavioral array viewed by others as being appropriate to human activity and successful living.

Alterations in Cognitive Systems

Consciousness is a state of awareness both of oneself and of the environment and a set of responses to that environment. Consciousness has two distinct components: arousal (state of wakefulness or alertness) and awareness (content of thought). Arousal is mediated by the reticular activating system, which regulates aspects of attention and information processing and maintains consciousness (see Fig. 15.7). Cognitive cerebral functions require a functioning reticular activating system (RAS). Awareness encompasses all cognitive functions and is mediated by attentional systems, memory systems, language systems, and executive systems.

Alterations in Arousal

Alterations in level of arousal may be caused by structural, metabolic, or psychogenic (functional) disorders.

Pathophysiology

Structural alterations in arousal are divided according to the original location of the pathologic condition: supratentorial (above the tentorium cerebelli—membrane), infratentorial (subtentorial, below the tentorium cerebelli—membrane) (see Figs. 15.17 and 17.17), extracerebral (outside the brain tissue), and intracerebral (within the brain tissue). Causes include infection, vascular alterations, neoplasms, traumatic injury, congenital alterations, degenerative changes, polygenic traits, and metabolic disorders.

Supratentorial disorders (above the tentorium cerebelli) produce changes in arousal by either diffuse or localized dysfunction. Diffuse dysfunction may be caused by disease processes affecting the cerebral cortex or the underlying subcortical white matter (e.g., encephalitis). Disorders outside the brain but within the cranial vault (extracerebral) also can produce diffuse dysfunction, including neoplasms, closed-head trauma with subsequent bleeding (i.e., subdural hematoma or subarachnoid hemorrhage), and subdural empyema (accumulation of pus). Disorders within the brain substance (intracerebral)—bleeding, infarcts, emboli, and tumors—function primarily as masses. Such localized destructive processes directly impair function of the thalamic or hypothalamic activating systems or secondarily compress these structures in a process of expansion or herniation.

Infratentorial disorders (below the tentorium cerebelli) produce a decline in arousal by (1) direct destruction or compression of the RAS and its pathways (e.g., accumulations of blood or pus, neoplasms, and demyelinating disorders), or (2) the brainstem (midbrain, pons, and medulla) may be destroyed either by direct invasion or by indirect impairment of its blood supply. The most common cause of direct destruction is cerebrovascular disease. Demyelinating diseases, neoplasms, granulomas, abscesses, and head injury also may cause brainstem destruction by tissue compression. This compression may occur because of (1) direct pressure on the pons and midbrain, producing ischemia and edema of the neurons of the RAS; (2) upward herniation of the cerebellum through the tentorial notch, thus compressing the upper midbrain and diencephalon; or (3) downward herniation of the cerebellum through the foramen magnum, compressing and displacing the medulla oblongata.

Metabolic alterations in arousal produce a decline in arousal by alterations in delivery of energy substrates as occurs with hypoxia, electrolyte disturbances, hypoglycemia, or hyperglycemia. Examples of systemic diseases that eventually produce nervous system disorders include liver or renal failure that cause alterations in neuronal excitability because of failure to metabolize or eliminate drugs and toxins. Hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency may be associated with alterations in arousal (e.g., myxedema coma and adrenal crisis) and are medical emergencies (see Chapter 22).

Psychogenic alterations in arousal (unresponsiveness), although uncommon, may signal general psychiatric disorders (see Chapter 19). Despite apparent unconsciousness, the person is physiologically awake, and the neurologic examination reflects normal responses.

Clinical Manifestations and Evaluation

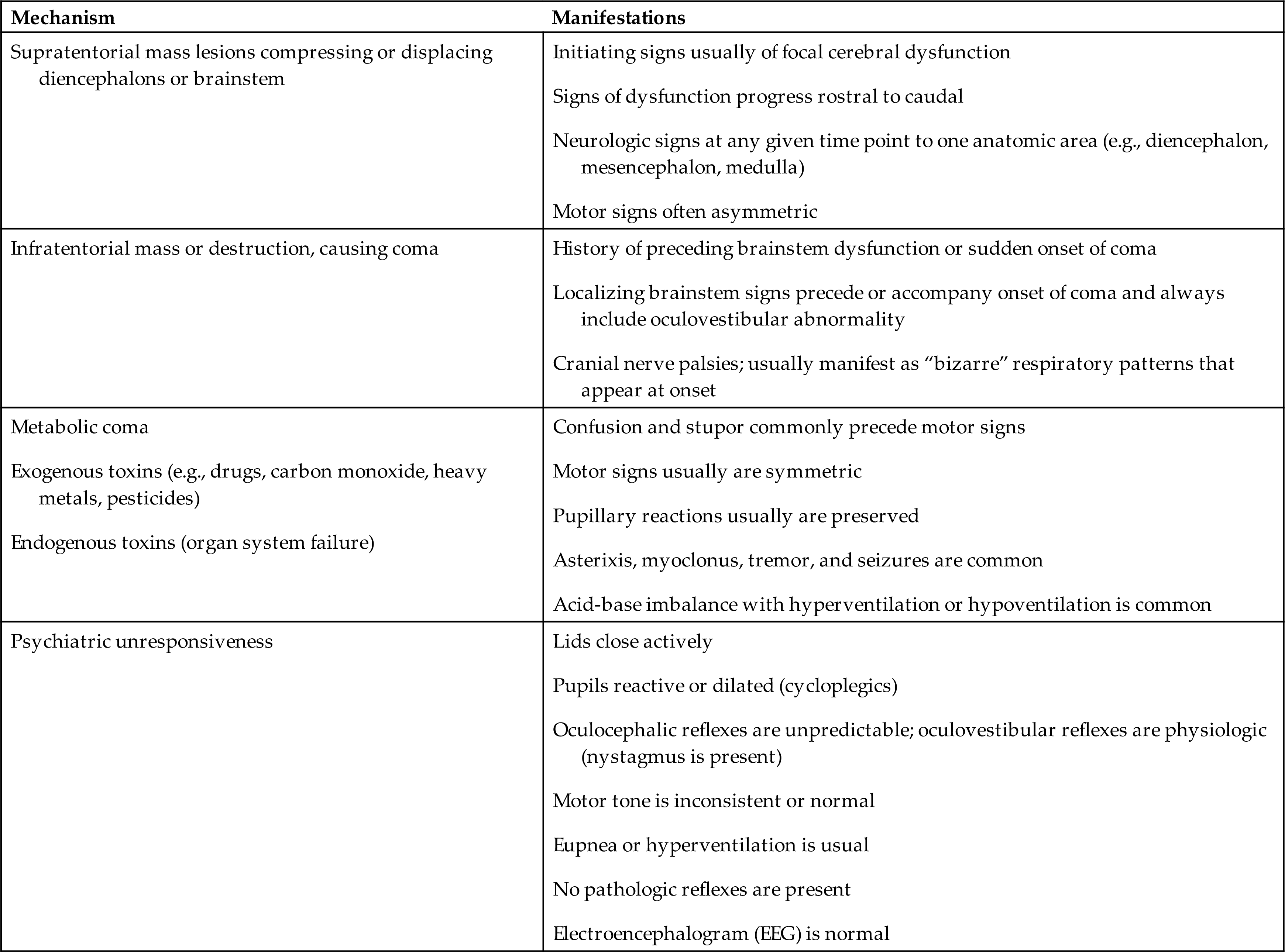

Five patterns of neurologic function are critical to the evaluation process: (1) level of consciousness, (2) pattern of breathing, (3) pupillary reaction, (4) oculomotor responses, and (5) motor responses. Patterns of clinical manifestations help determine the extent of brain dysfunction and serve as indices for identifying increasing or decreasing central nervous system (CNS) function. Distinctions are made between metabolic and structurally induced manifestations (Table 17.1). The types of manifestations suggest the mechanisms of the altered arousal state (Table 17.2).

Table 17.1

Table 17.2

Patterns of Neurologic Function

Level of consciousness is the most critical clinical index of nervous system function, with changes indicating either improvement or deterioration of the individual's condition. A person who is alert and oriented to self, others, place, and time is functioning at the highest level of consciousness, which implies full use of all the person's cognitive capacities. From this normal alert state, levels of consciousness diminish in stages from confusion and disorientation (can occur simultaneously) to coma, each of which is clinically defined (Table 17.3). Guidelines are available to assist with the evaluation of prolonged disorders of consciousness.2

Table 17.3

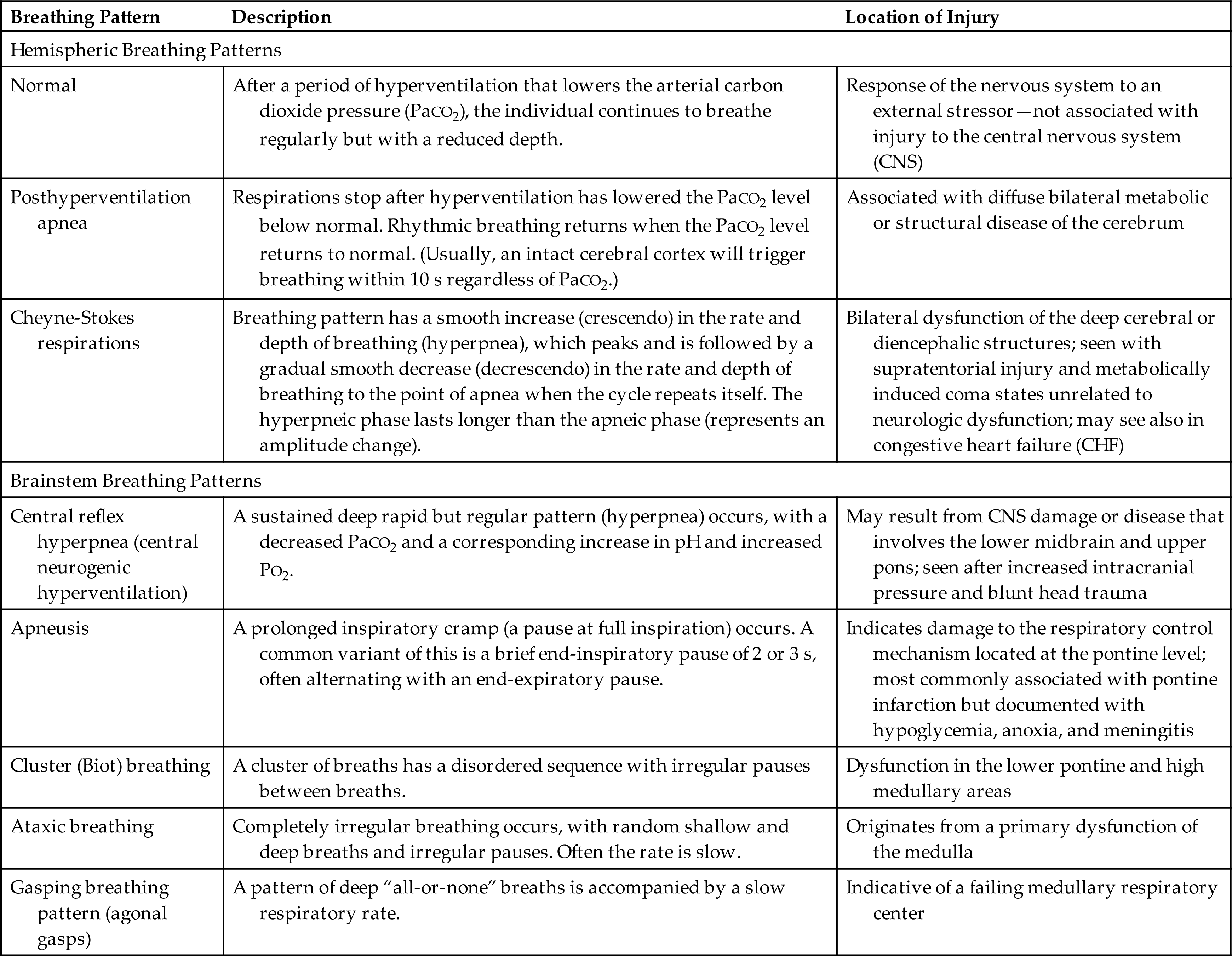

Patterns of breathing help evaluate the level of brain dysfunction and coma. Rate, rhythm, and pattern should be evaluated. Breathing patterns can be categorized as hemispheric or brainstem (Table 17.4 and Fig. 17.1).

Table 17.4

(A) Cheyne-Stokes respiration is seen with metabolic injury and lesions in the forebrain and diencephalon. (B) Central neurogenic hyperventilation is most commonly seen with metabolic encephalopathies (lesion of midbrain, pons, or medulla). (C) Apneustic breathing (inspiratory pauses) is seen in persons with bilateral pontine lesions. (D) Cluster (Biots) breathing and ataxic breathing are seen in lesions at the pontine medullary junction. (E) Ataxic breathing occurs when the medullary ventral respiratory nuclei are injured. (From Urden LD, et al. Critical care nursing: Diagnosis and management, 6th edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2010.)

An illustration depicts the abnormal respiratory patterns associated with pathologic lesions at various levels of the brain. Tracings by chest-abdomen pneumograph, inspiration reads up. A; Cheyne-stokes respiration. B; Central neurogenic hyperventilation. C; Apneusis. D; Cluster breathing. E; Ataxic breathing.

With normal breathing, a neural center in the forebrain (cerebrum) produces a rhythmic breathing pattern. When consciousness decreases, lower brainstem centers regulate the breathing pattern by responding only to changes in PaCO2 levels. This pattern is called posthyperventilation apnea (PHVA).

Cheyne-Stokes respiration is an abnormal rhythm of ventilation (periodic breathing) with alternating periods of hyperventilation and apnea (crescendo-decrescendo pattern). In the damaged brain, higher levels of PaCO2 are required to stimulate ventilation, and increases in PaCO2 lead to tachypnea. The PaCO2 level then decreases to below normal and breathing stops (apnea) until the carbon dioxide reaccumulates and again stimulates tachypnea (see Fig. 17.1). In cases of opiate or sedative drug overdose, the respiratory center is depressed, and the rate of breathing gradually decreases until respiratory failure occurs.

Central neurogenic hyperventilation is a respiratory pattern of sustained hyperventilation caused by a lesion that stimulates the respiratory center in the central pons. Apneustic respirations have prolonged inspiratory phase and a short expiratory phase caused by injury to the pons or upper medulla. Cluster (Biots) respirations are characterized by periods or clusters of rapid respirations of near equal depth resulting from trauma or compression to the medulla near the pontine junction or from chronic opioid abuse. Ataxic respirations are variable respirations with irregular prolonged periods of apnea associated with damage to the medulla (see Fig. 17.1).

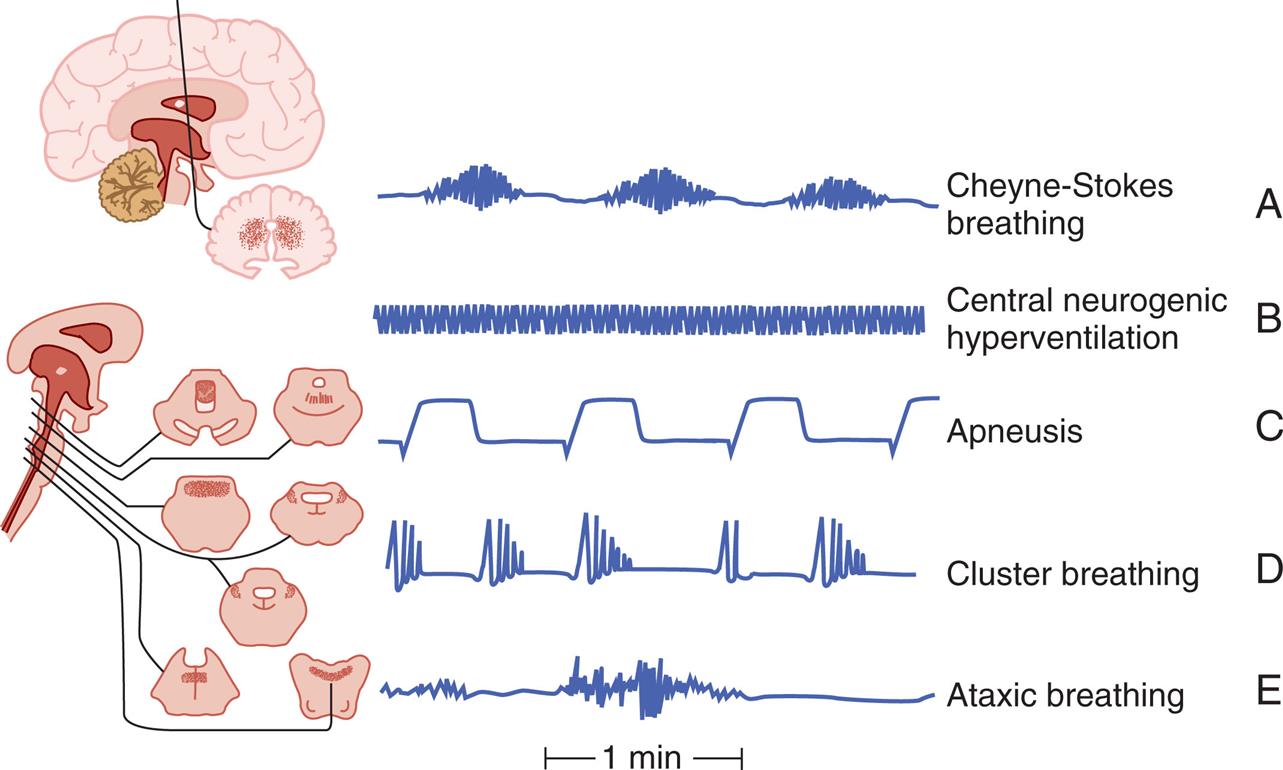

Pupillary changes indicate the presence and level of brainstem dysfunction because brainstem areas that control arousal are adjacent to areas that control the pupils (Fig. 17.2). For example, severe ischemia and hypoxia usually produce dilated, fixed pupils. Hypothermia may cause fixed pupils. Some drugs affect pupils and must be considered in evaluating individuals in comatose states. Large doses of atropine and scopolamine (drugs that block parasympathetic stimulation) fully dilate and fix pupils. Doses of sedatives (e.g., glutethimide) in sufficient amounts to produce coma cause the pupils to become mid-position or moderately dilated, unequal, and commonly fixed to light. Opiates (which stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system) cause pinpoint pupils.

A series of illustrations shows the appearance of pupils at different levels of consciousness with reference to the brain stem. The six appearances are as follows. • Metabolic imbalance or deep bilateral hemisphere lesion such as hydrocephalus or thalamic hemorrhage. The pupils are small, receptive, and regular. • Dysfunction of tectum (roof) of the midbrain; large, fixed hippus. • Pontine dysfunction; pinpoint. • Midbrain dysfunctional; midposition and fixed. • Dysfunction of third cranial nerve sluggish, dilated, and fixed. • Diencephalic dysfunction; small and reactive.

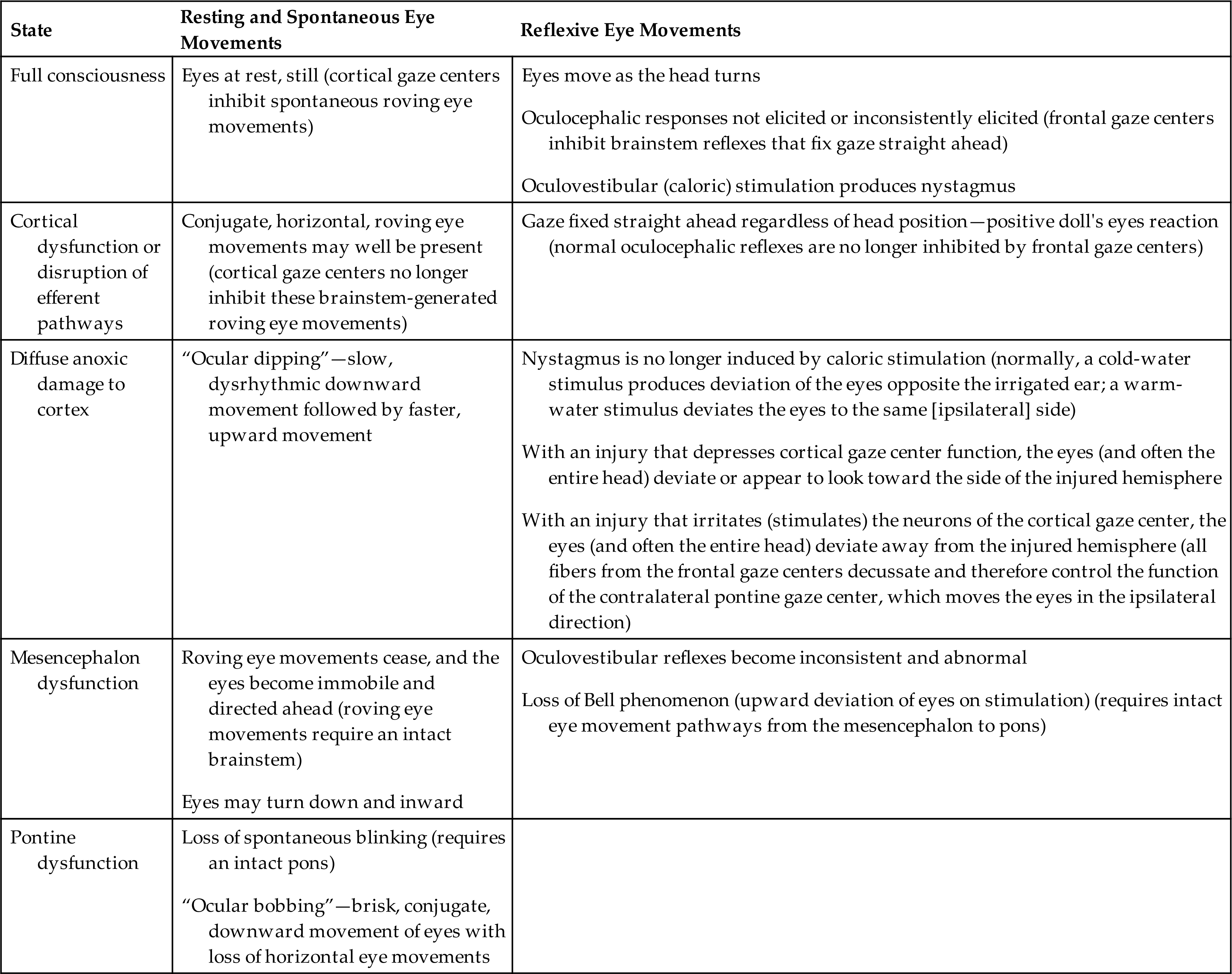

Oculomotor responses are resting, spontaneous, and reflexive eye movements. They change at various levels of brain dysfunction in comatose individuals (Table 17.5). Persons with metabolically induced coma, except in cases of barbiturate-hypnotic and phenytoin (Dilantin) poisoning, generally retain ocular reflexes, even when other signs of brainstem damage, such as central neurogenic hyperventilation, are present.

Table 17.5

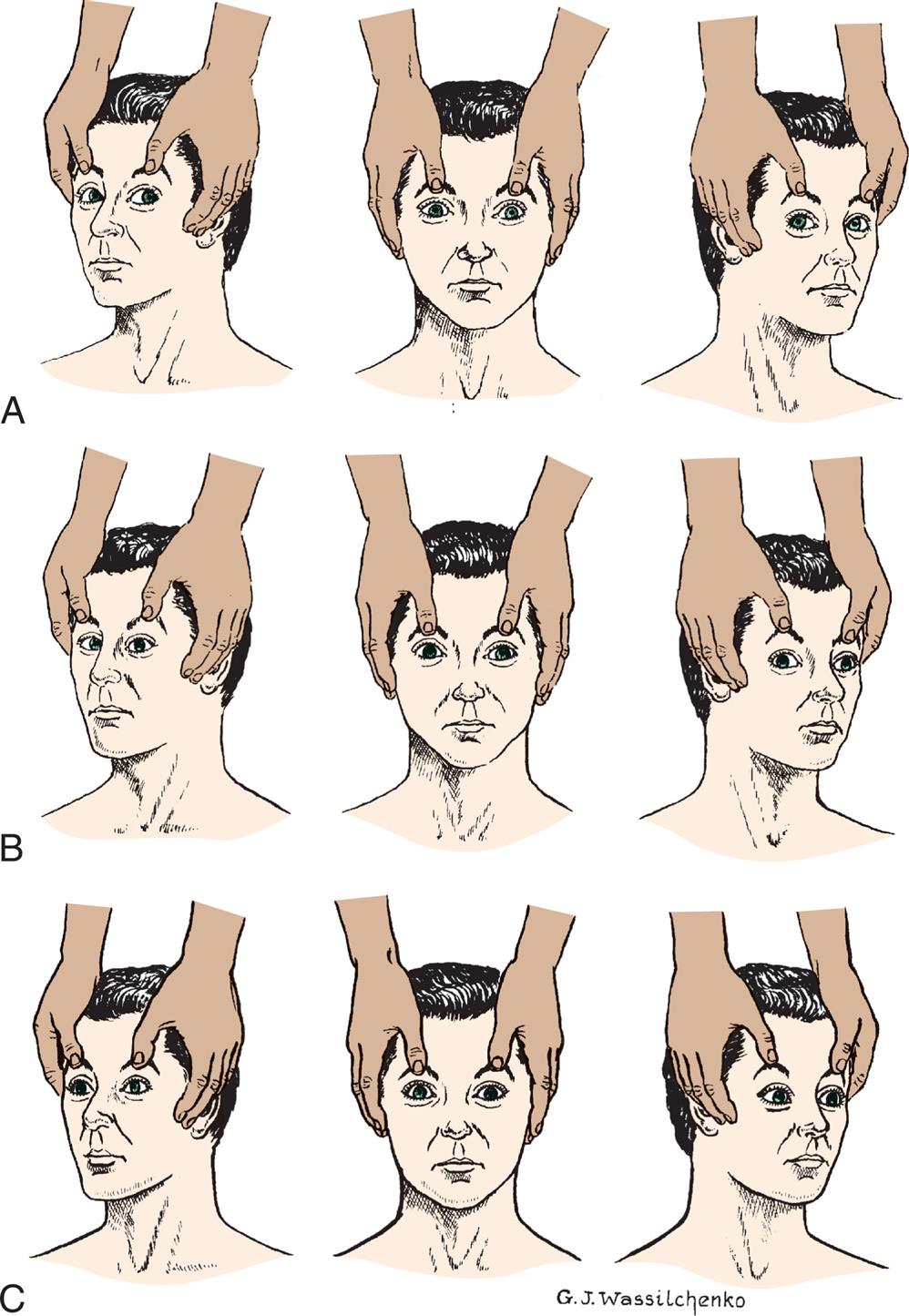

The presence of brisk oculocephalic reflexes and roving eye movements, as well as the failure to elicit nystagmus with instillation of cold or warm water into the external ear canal, indicates a decrease in consciousness (loss of cortical influence) but an intact brainstem (Figs. 17.3 and 17.4).

(A) Normal response—eyes turn together to side opposite from turn of head. (B) Abnormal response—eyes do not turn in conjugate manner. (C) Absent response—eyes do not turn as head position changes. (A and C, From Rudy EB. Advanced neurological and neurosurgical nursing. St. Louis: Mosby; 1984.)

Three sets of illustrations demonstrate the test for oculocephalic reflect response. Each set shows a pair of hands positioned on the sides of a person’s face with the thumbs pulling upward on the eyebrows. In each set, the illustration on the left shows the head turned to the right, the illustration in the middle shows the head facing forward, and the illustration on the right shows the head turned toward the left. Top panel, A. The positions of the pupils are as follows. On the left, the pupils look to the left together. In the middle, the pupils look straight ahead together. On the right, the pupils look to the right together. Middle panel, B. The positions of the pupils are as follows. On the left, the pupils are converged toward the nose. In the middle, the pupils look straight ahead together. On the right, the right pupil looks to the right, while the pupil on the left look straight ahead. Bottom panel, C. The positions of the pupils are as follows. On the left, in the middle, and on the right, the pupils look absently straight ahead.

(A) Normal response—conjugate eye movements. (B) Abnormal response—dysconjugate or asymmetric eye movements. (C) Absent response—no eye movements.

Three illustrations, A, B, and C, demonstrate the test of oculovestibular reflex. Each illustration shows a person's head in supine position, a hand pressing down on the head, and a syringe pressed into the right ear. Left panel, A. The pupils look together on the right, toward the syringe. Middle panel, B. The right pupil looks straight ahead, while the left pupil looks to the right. Right panel, C. Both pupils look straight ahead together.

Destructive or compressive injury to the brainstem causes specific abnormalities of the oculocephalic and oculovestibular reflexes. For example, a skewed deviation, in which one eye diverges downward and the other looks upward, indicates brainstem dysfunction. Destructive or compressive disease processes that involve an oculomotor nucleus or nerve cause the involved eye to deviate outward, producing a resting dysconjugate lateral position of the eyes (each eye diverges laterally). Unilateral abducens paralysis (paralysis of cranial nerve VI) results in an upward deviation of the ipsilateral eye. With bilateral abducens paralysis, the eyes come together (converge). Reflexive eye movements may be suppressed by drugs, most commonly phenytoin, tricyclics, and barbiturates. Occasionally alcohol, phenothiazines, and diazepam may alter reflex eye movements.

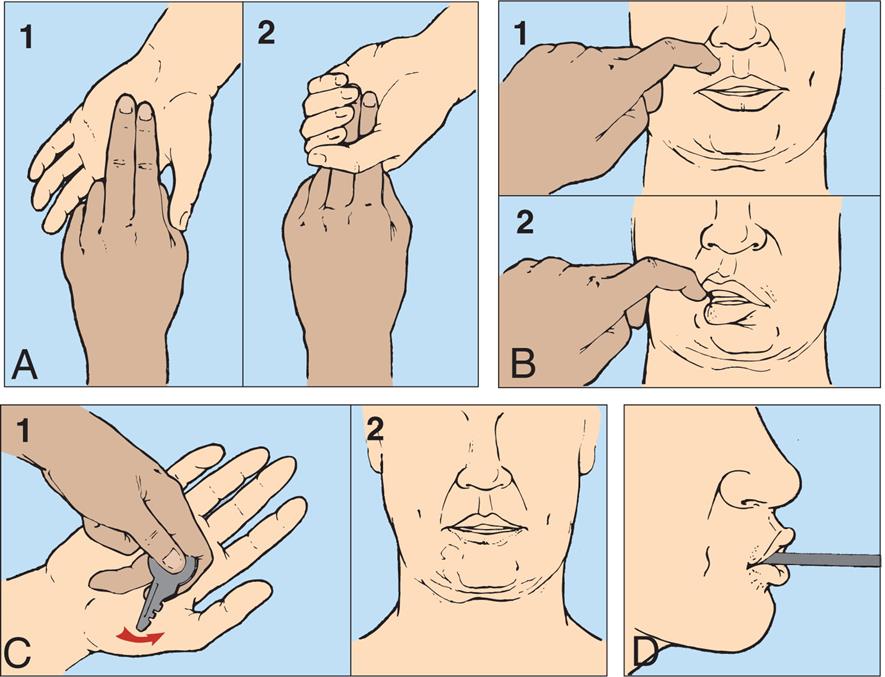

Assessment of motor responses helps to evaluate the level of brain dysfunction and determine the side of the brain that is maximally damaged. The pattern of response noted may be (1) purposeful (a defensive or withdrawal movement of limbs to noxious stimuli); (2) inappropriate, or not purposeful (generalized motor movement, posturing, grimacing, or groaning); or (3) not present (unresponsive, no motor response). Purposeful movement requires an intact corticospinal system. Nonpurposeful movement is evidence of severe dysfunction of the corticospinal system.

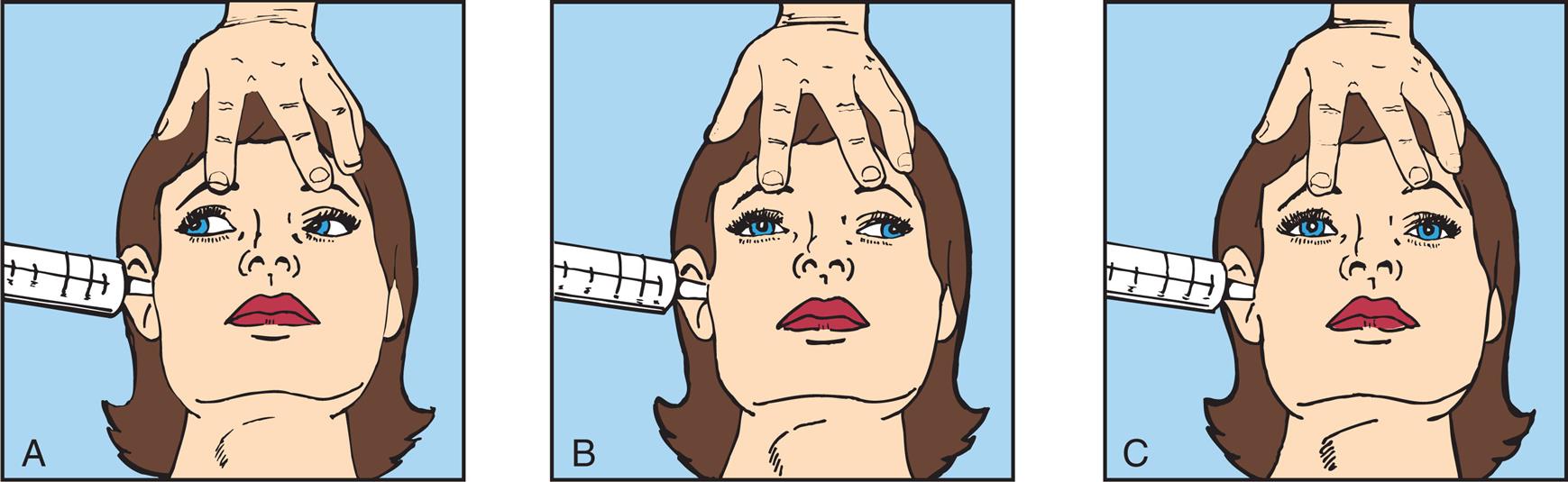

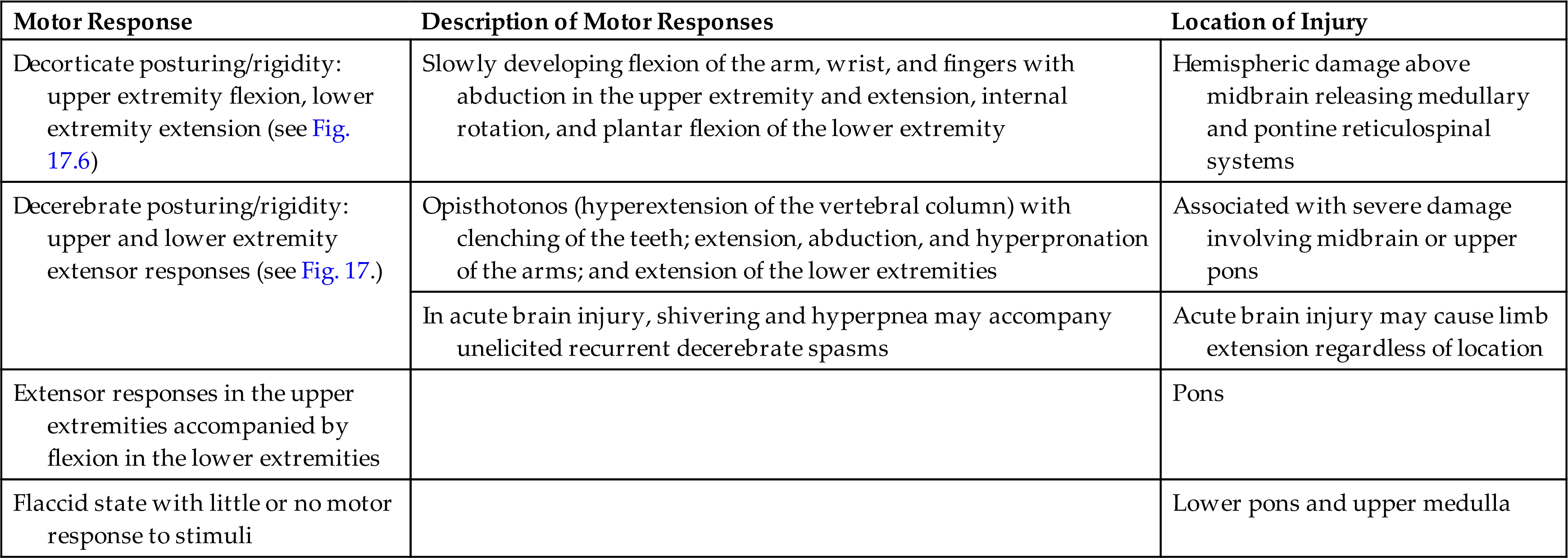

Motor signs indicating loss of cortical inhibition are commonly associated with decreased consciousness and include primitive reflexes and rigidity (paratonia). Primitive reflexes include grasping, reflex sucking (tapping on lips stimulates sucking), snout reflex (tapping of closed lips at midlines causes pursing of lips), and palmomental reflex (stroking palm causes twitch of chin muscle), all of which are normal in the newborn but disappear in infancy (Fig. 17.5). Abnormal flexor and extensor responses in the upper and lower extremities are defined in Table 17.6 and illustrated in Fig. 17.6.

(A) Primitive reflexes include grasping. (A1) Absent grasp; (A2) Grasp present. (B) Reflex sucking (tapping on lips stimulates sucking). (B1) Absent reflex. (B2) Reflex present. (C) Palmomental reflex. (C1) Stroking palm causes (C2) twitch of chin muscle. (D) Snout reflex (tapping of closed lips at midlines causes pursing of lips). (D1) Absent reflex. (D2) Reflex present.

Four pairs of illustrations, A, B, C, and D, demonstrate pathologic reflexes. Top-left panel, A. The illustration on the left, 1, shows two hands. The index and the middle fingers of one hand are placed on the open palm of the other hand. The illustration on the right, 2, shows the palm closed around the two fingers on the other hand. Top-right panel, B. The illustration on the left, 1, shows an index finger pressing above the upper lip. The illustration on the right, 2, shows the lips turned toward the finger, sucking. Bottom-left panel, C. The illustration on the left, 1, shows a hand holding a key and stroking near the thumb of an open palm. The illustration on the right, 2, shows the twitching chin of a person. Bottom-right panel, D. The illustration shows the right lateral profile of the lower jaw of a person. The lips are pursed around a pencil-like object.

Table 17.6

| Motor Response | Description of Motor Responses | Location of Injury |

|---|---|---|

| Decorticate posturing/rigidity: upper extremity flexion, lower extremity extension (see Fig. 17.6) | Slowly developing flexion of the arm, wrist, and fingers with abduction in the upper extremity and extension, internal rotation, and plantar flexion of the lower extremity | Hemispheric damage above midbrain releasing medullary and pontine reticulospinal systems |

| Decerebrate posturing/rigidity: upper and lower extremity extensor responses (see Fig. 17.) | Opisthotonos (hyperextension of the vertebral column) with clenching of the teeth; extension, abduction, and hyperpronation of the arms; and extension of the lower extremities | Associated with severe damage involving midbrain or upper pons |

| In acute brain injury, shivering and hyperpnea may accompany unelicited recurrent decerebrate spasms | Acute brain injury may cause limb extension regardless of location | |

| Extensor responses in the upper extremities accompanied by flexion in the lower extremities | Pons | |

| Flaccid state with little or no motor response to stimuli | Lower pons and upper medulla |

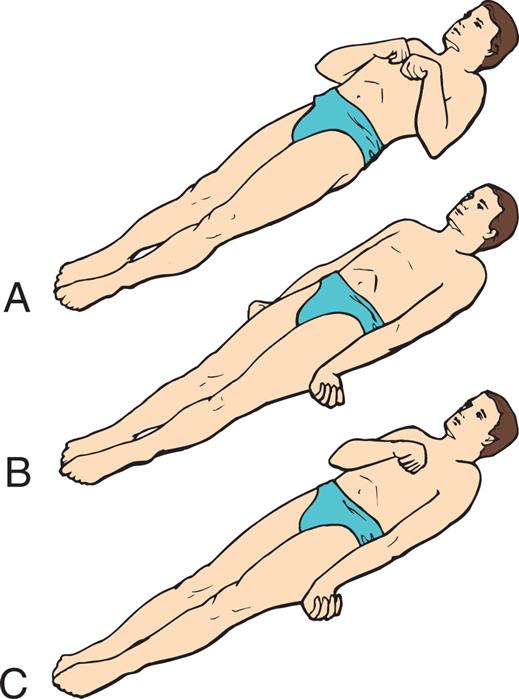

(A) Decorticate response (flexor posturing): bilateral flexion of elbows and wrists with shoulder adduction in upper extremities. Extension, internal rotation of lower extremities (lesions above the midbrain). (B) Decerebrate response (extensor posturing): all four extremities in rigid extension, internal rotation of shoulders with hyperpronation of forearms (midbrain lesions). (C) Decorticate response on right side of body and decerebrate response on left side of body: the most pronounced response differences are in the upper body. (From Rudy EB. Advanced neurological and neurosurgical nursing. St. Louis: Mosby; 1984.)

Three illustrations of a person in supine position demonstrate the decorticate and decerebrate responses. Top panel, A. The illustration shows the person’s arms flexed with the hands together on the chest. The feet are pointed forward. Middle panel, B. The illustration shows the person’s arms on their sides, the hands flexed outward, and the feet pointing forward. Bottom panel, C. The illustration shows one arm of the person on the side, the other arm flexed with the wrist on the chest, and the feet pointing forward.

Vomiting, yawning, and hiccups are complex reflex-like motor responses that are integrated by neural mechanisms in the lower brainstem. These responses may be produced by compression or diseases involving tissues of the medulla oblongata (e.g., infection, neoplasm, infarct, or other more benign stimuli to the vagal nerve). Most CNS disorders produce nausea and vomiting. Vomiting without nausea indicates direct involvement of the central neural mechanism (or pyloric obstruction). Vomiting often accompanies CNS injuries that (1) involve the vestibular nuclei or its immediate projections, particularly when double vision (diplopia) also is present; (2) impinge directly on the floor of the fourth ventricle; or (3) produce brainstem compression secondary to increased intracranial pressure (IICP).

Complications of Alterations in Arousal

Complications of alterations in arousal fall into two categories: extent of disability (morbidity) and mortality. The outcomes depend on the cause and extent of brain damage and the duration of coma. Some individuals may recover consciousness and an original level of function, some may have permanent disability, and some may never regain consciousness and experience neurologic death. Two forms of neurologic death—brain death and cerebral death—result from severe pathologic conditions and are associated with irreversible coma. Other possible outcomes are a vegetative state (VS), a minimally conscious state (MCS), or locked-in syndrome. The extent of disability has four subcategories: recovery of consciousness, residual cognitive function, psychologic function, and vocational function. Technological advances in imaging, including functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), have provided new opportunities for assessing cognition and detecting consciousness for individuals in a prolonged coma.3

Brain death (total brain death) occurs when brain damage is so extensive that it can never recover (irreversible) and cannot maintain the body's internal homeostasis. State laws define brain death as irreversible cessation of function of the entire brain, including the brainstem and cerebellum. On postmortem examination, the brain is autolyzing (self-digesting) or already autolyzed. Brain death has occurred when there is no evidence of brain function for an extended period.4 The abnormality of brain function must result from structural or known metabolic disease and must not be caused by a depressant drug, alcohol poisoning, or hypothermia. An isoelectric, or flat, electroencephalogram (EEG) (electrocerebral silence) for 6 to 12 hours in a person who is not hypothermic and has not ingested depressant drugs indicates brain death. The clinical criteria used to determine brain death are noted in Box 17.1. A task force for determination of brain death in children recommended the same criteria as for adults but with a longer observation period.5,6

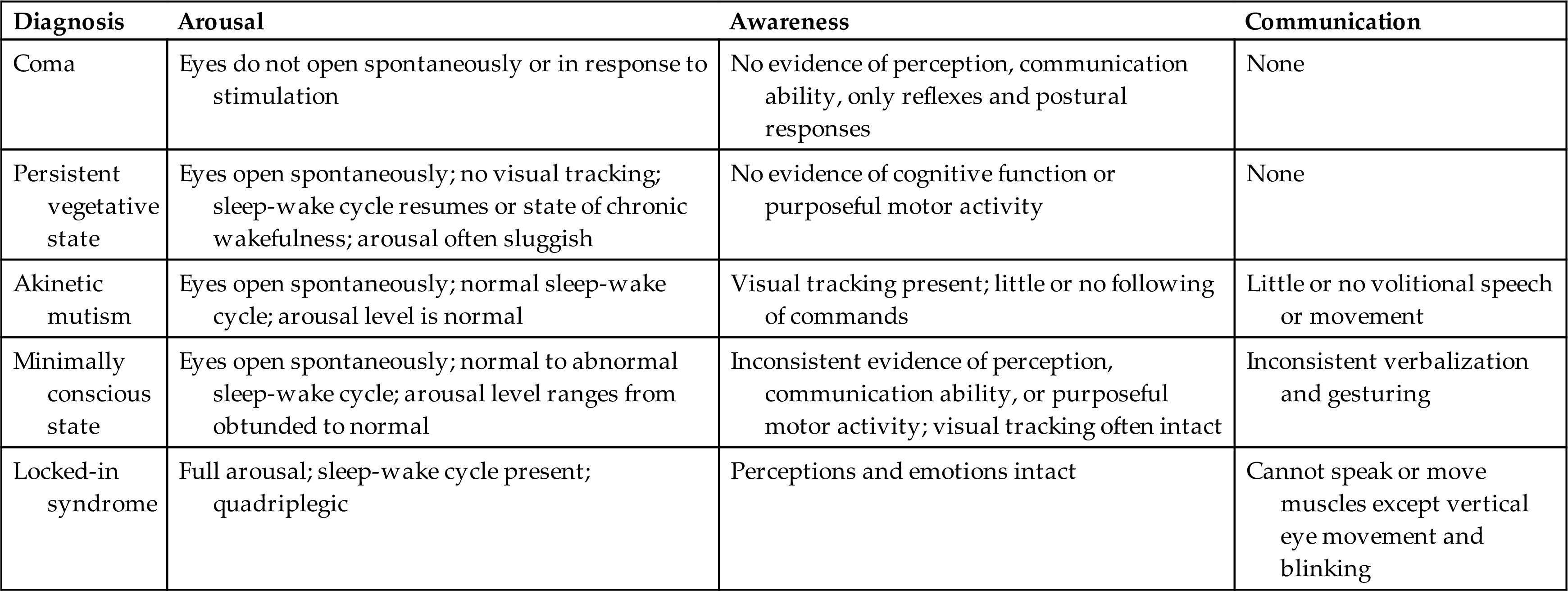

Cerebral death or irreversible coma is death of the cerebral hemispheres exclusive of the brainstem and cerebellum. Brain damage is permanent, and the individual is unable to ever respond behaviorally in any significant way to the environment. The brainstem may continue to maintain internal homeostasis (i.e., body temperature, cardiovascular functions, respirations, and metabolic functions). The survivor of cerebral death may remain in a coma or emerge into a persistent VS or a MCS. In coma, the eyes are usually closed with no eye opening. The person does not follow commands, speak, or have voluntary movement (Table 17.7).

Table 17.7

Data from Giacino JT, Ashwal S, Childs N, et al. The minimally conscious state: Definition and diagnostic criteria. Neurology, 2002;58(3):349–353; Owen AM. Disorders of consciousness. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2008;1125:225–238.

A persistent VS, or unresponsive wakefulness syndrome, is complete unawareness of the self or surrounding environment and complete loss of cognitive function. The individual does not speak any comprehensible words or follow commands.7 Sleep-wake cycles are present, eyes open spontaneously, and blood pressure and breathing are maintained without support. Brainstem reflexes (pupillary, oculocephalic, chewing, swallowing) are intact but cerebral function is lost. There may be random hand, extremity, or head movements. There is bowel and bladder incontinence. Recovery is unlikely if the state persists for 12 months.

In a MCS, individuals may follow simple commands; manipulate objects; gesture or give yes/no responses; have intelligible speech; and have movements, such as blinking or smiling, that occur in a meaningful relationship to the eliciting stimulus and are not attributable to reflexive activity.8

With locked-in syndrome (ventral pontine syndrome), there is complete paralysis of voluntary muscles apart from vertical gaze and upper eyelid movement. Content of thought and level of arousal are intact, but the efferent pathways are disrupted (injury at the base of the pons with the reticular formation intact, often caused by basilar artery occlusion).9 The individual cannot communicate either through speech or through body movement but is fully conscious with intact cognitive function. The upper cranial nerves (I to IV) often are preserved so that the person possesses vertical eye movement and blinking as a means of communication.

Akinetic mutism (AM) is a rare neurobehavioral state characterized by a severe loss of motivation to move or inability to voluntarily initiate goal-directed motor responses (akinetic), including speech (mutism), gestures, and facial expression. Generally, these individuals are alert, orient to external stimuli, and can follow the examiner with their eyes but do not initiate other voluntary activity or movement. This is not attributable to decreased wakefulness, motor weakness, or paralysis but rather a lack of “willfulness” to do so. The neuropathology is different when compared with the VS and locked-in syndrome and involves damage to frontal-subcortical structures involved in the translation of a motivational stimulus to a behavioral response. It may occur with cerebrovascular disease, obstructive hydrocephalus, or be associated with tumors. Combined deficits of vigilance, detection, and working memory accompanied by other deficits of the cognitive systems are common.10

Alterations in Awareness

Awareness (content of thought) encompasses all cognitive functions, including awareness of self, environment, affective states (i.e., moods), and memory. Awareness is mediated by all the core networks under the guidance of executive attention networks, including selective attention and memory. Executive attention networks involve abstract reasoning, planning, decision making, judgment, error correction, and self-control. Each attentional function is a network of interconnected brain circuits and not localized to a single brain area.

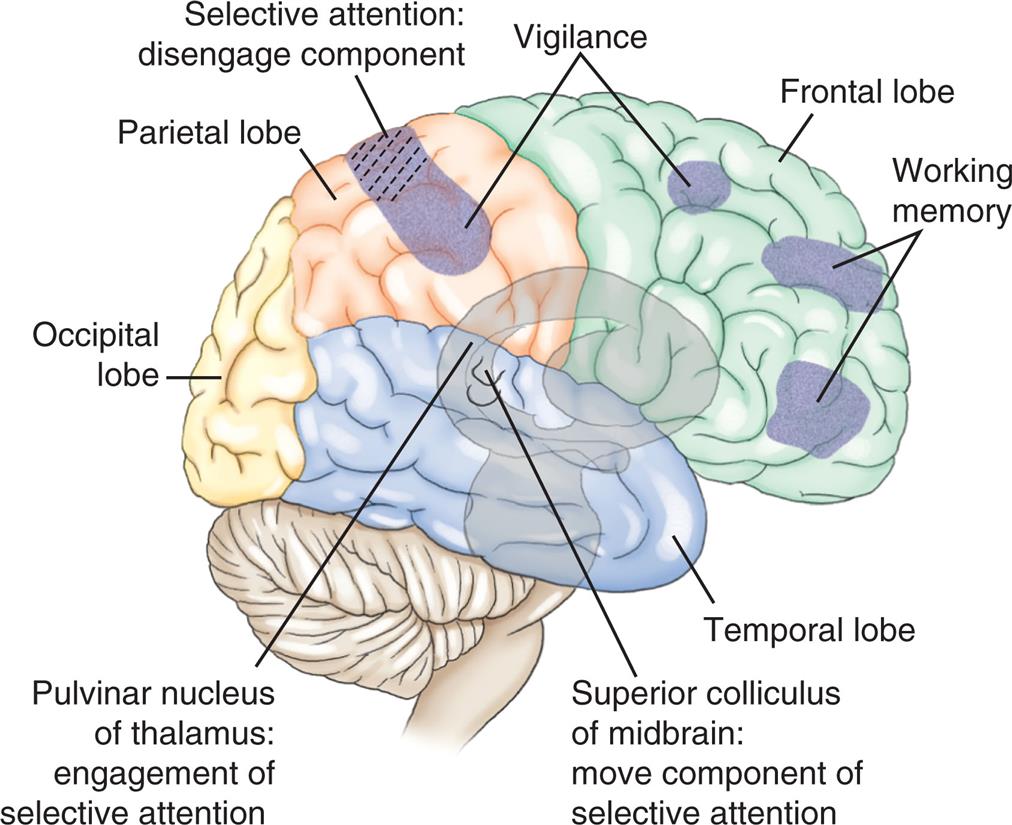

Selective attention (orienting) refers to the ability to select specific information to be processed from available, competing environmental and internal stimuli and to focus on that stimulus (i.e., to concentrate on a specific task without being distracted) to guide behavior. Selective visual (spatial) attention is the ability to select objects/events from multiple visual stimuli (location and movement in visual space) and process them to complete a task. Selective auditory or hearing attention is the ability to select or filter specific sounds and process them to complete a task. Multiple areas of the brain are involved in selective attention, including cortical areas, thalamic nuclei, and the limbic system. Frontal and parietal regions of the right hemisphere contribute to selective attention. The engagement component (identifying the target of attention) is mediated by the pulvinar nucleus of the thalamus and regulates cortical synchrony (Fig. 17.7).11 The disengagement mechanism (shifting attention to a new target and re-engaging on the new target) is mediated by the right parietal lobe. The motor consequences of attention are mediated by the superior colliculus for visual orienting and spatial attention.12

An illustration of the right lateral view of the brain shows and labels the following structures, clockwise from the top: vigilance, frontal lobe, working memory, temporal lobe, superior colliculus of midbrain (move component of selective attention), pulvinar nucleus of thalamus (engagement of selective attention), occipital lobe, parietal lobe, and selective attention (disengage component).

Selective attention deficits can be temporary, permanent, or progressive. Disorders associated with selective attention deficits include seizure activity, parietal lobe contusions, subdural hematomas, stroke, gliomas or metastatic tumor, late Alzheimer dementia, frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and psychotic disorders. Disorders of selective attention related to visual orienting behavior are produced by disease that involves portions of the midbrain. Disease affecting the superior colliculi manifests as a slowness in orienting attention. Parietal lobe disease may produce unilateral neglect syndrome, which is failure to report, respond, or orient to visual, auditory, or tactile stimuli that are presented contralateral to a brain lesion, provided this failure is not explained by primary sensory or motor disorders. For example, an individual with neglect following a right hemisphere lesion may fail to recognize a left limb, read from the left side of a book, ignore the food on the left side of the plate, remain unaware of numerals on the left side of a clock, or have an abnormal rightward shift in head and eye position. The person can recognize individual sensory input from the ipsilateral side (the side with the hemispheric lesion) when asked but ignores (i.e., neglects, extinguishes) the sensory input from the contralateral side when stimulated from both sides. This phenomenon is called extinction.13 The entire complex of sensory inattentiveness, loss of recognition of one's own body parts, and extinction, sometimes referred to as neglect syndrome, is common after stroke, generally in the right hemisphere.14

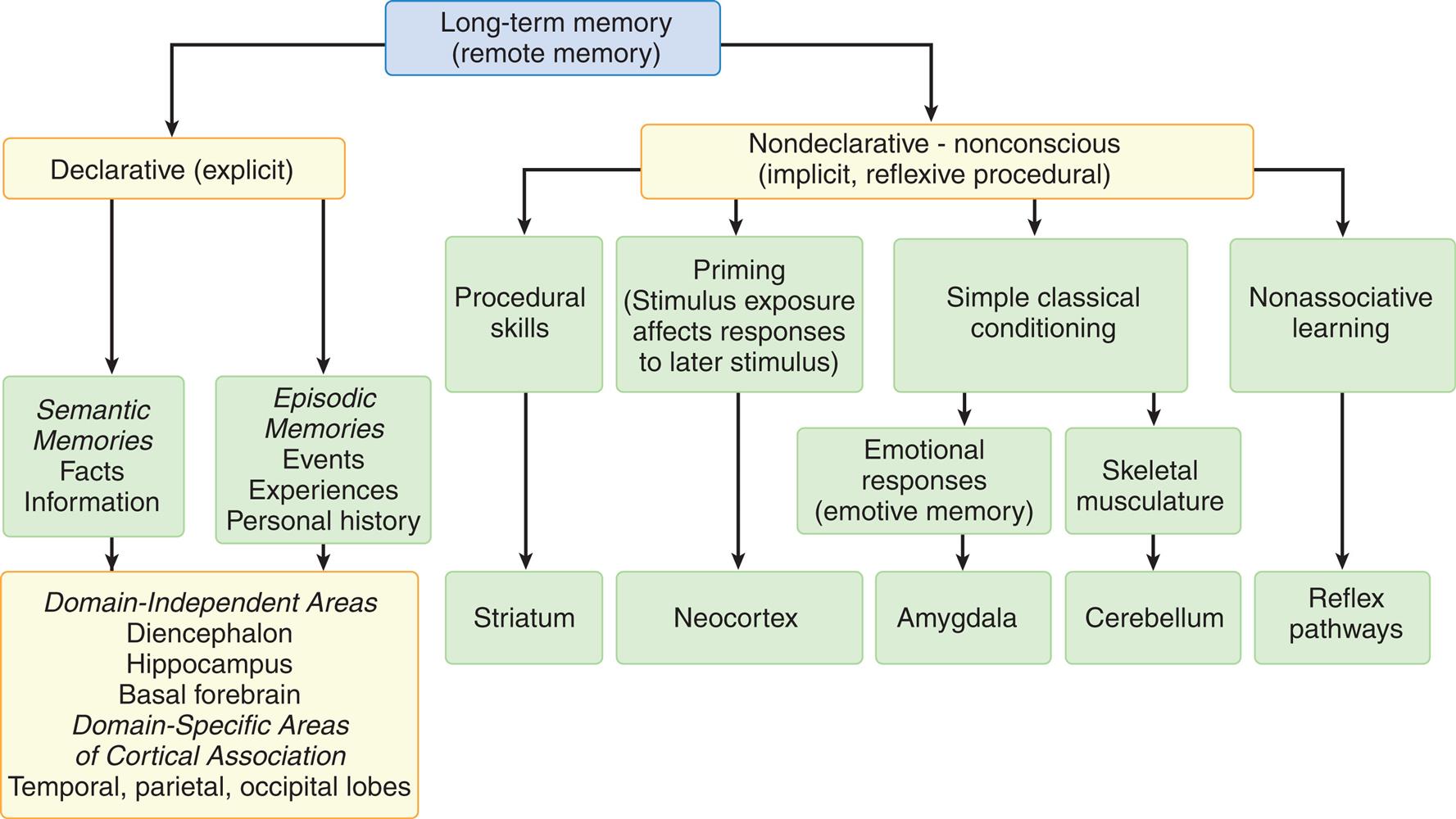

Memory is the recording, retention, and retrieval of information. Two types of long-term memory exist: declarative and nondeclarative (Fig. 17.8).168

A hierarchy diagram represents the types of memory and associated brain systems. Long-term memory (remote memory) is one of the following two types. • Declarative (explicit). • Nondeclarative - nonconscious (implicit, reflexive procedural). Declarative (explicit) memory stores the following two types of data. • Semantic, memories, facts, information. • Episodic, memories, events, experiences, personal history. The brain systems associated with both types of data are as follows: domain-independent areas, diencephalon, hippocampus, basal forebrain, domain-specific areas of cortical association, and temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. Nondeclarative - nonconscious (implicit, reflexive procedural) memory stores the following types of data. • Procedural skills (associated with striatum). • Priming (stimulus exposure affects responses to later stimulus) (associated with neocortex). • Simple classical conditioning (emotional responses or emotive memory; skeletal musculature). • Nonassociative learning (associated with reflex pathways). Emotional responses are associated with the amygdala. Skeletal musculature is associated with cerebellum.

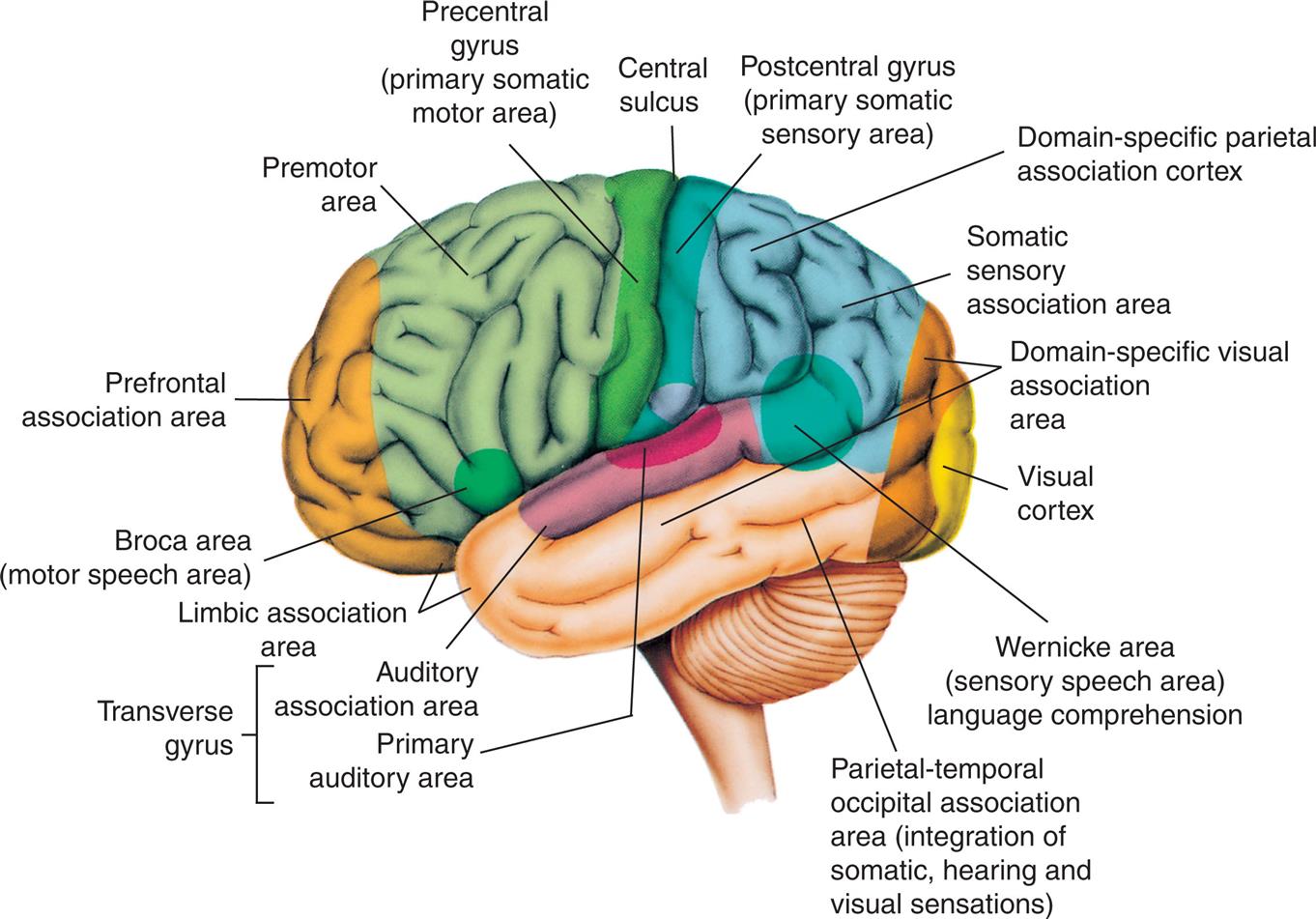

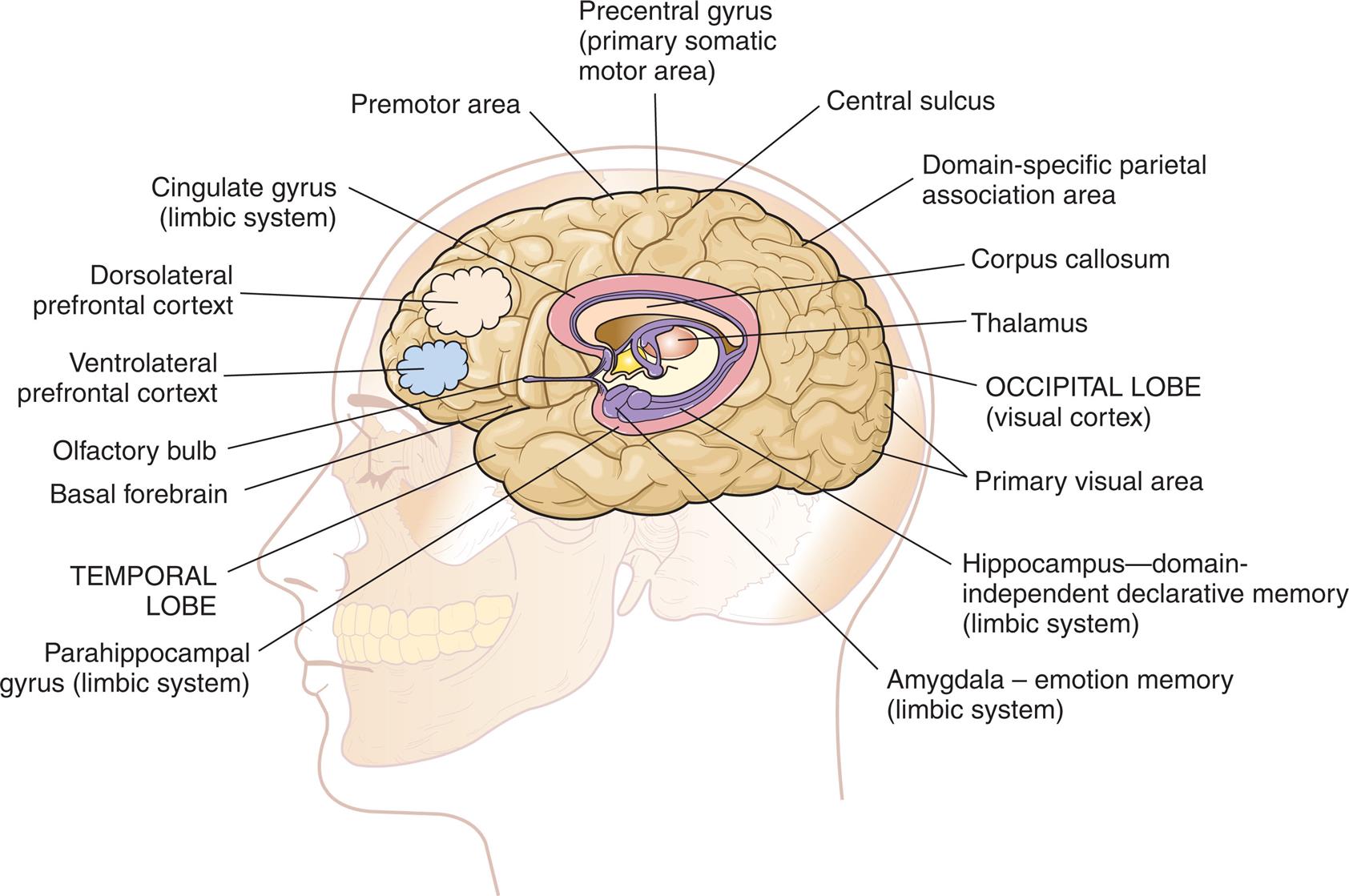

Declarative memory (conscious or explicit) involves the learning and remembrance of episodic memories (personal history and the where, what, and when of events and experiences) and semantic memories (facts and information). Declarative memory is mediated by domain-specific cortical areas of the association areas. This includes (1) areas of the temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes (Fig. 17.9), where long-term memories are thought to be stored; and (2) domain-independent areas of the medial temporal lobe (e.g., hippocampus), the diencephalon (thalamic structures and hypothalamus), and the basal forebrain (located ventral to the striatum and produces acetylcholine) (Fig. 17.10), where it is thought distinct, domain-specific features of an experience are related or bound.168

An illustration of the left lateral view of the brain highlights the cortical areas of the left (dominant) hemisphere. The followings structures on the brain are labels, from the forebrain to the hindbrain: Broca area (motor speech area), prefrontal association area, premotor area, precentral gyrus (primary somatic motor area), central sulcus, postcentral gyrus (primary somatic sensory area), domain-specific parietal association cortex, somatic sensory association area, domain-specific visual association area, visual cortex, Wernicke area (sensory speech area) language comprehension, parietal-temporal occipital association area (integration of somatic, hearing, and visual sensations), transverse gyrus (auditory association area, primary auditory area), and limbic association area.

An illustration of the left lateral view of the brain in a person’s head shows and labels the following structures, from the forebrain to the hindbrain: olfactory bulb, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, cingulate gyrus (limbic system), premotor area, precentral gyrus (primary somatic motor area), central sulcus, domain-specific parietal association area, corpus callosum, thalamus, occipital lobe (visual cortex), primary visual area, hippocampus-domain-independent declarative memory (limbic system), amygdala - emotion memory (limbic system), parahippocampal gyrus (limbic system), and temporal lobe.

Nondeclarative memory (nonconscious), also called reflexive, procedural, or implicit memory, is the memory for actions, behaviors (habits), skills, and outcomes.168 It is not a language memory but a motor memory. Nondeclarative memory involves the construction of the motor pattern so that the action, behavior, or skill becomes increasingly automatic. The striatum of the basal ganglia supports this learning across trials (stimulus-response learning), as well as probabilistic classification learning, which supports outcome prediction. All skills and habits are stored in this memory network.15Cerebellar memory is involved in working memory (short term memory), in addition to motor coordination and nonmotor functions of cognition, emotion, and learning.16Emotional memory is mediated by the amygdala (located on the inner surface of the temporal lobe) (see Fig. 17.10) and other neural networks. The amygdala attaches positive (e.g., pleasure) or negative (e.g., fear) dispositions to stimuli in the absence of conscious recollection of the circumstances of the emotional experience.17

Amnesia is the loss of memory and can be mild or severe. Two types of amnesia are retrograde amnesia and anterograde amnesia. The person experiencing retrograde amnesia has difficulty retrieving past personal history memories or past factual memories. In anterograde amnesia, new personal or factual memories cannot be formed, but memories of the distant past are retained and retrieved. These are disorders of domain-independent declarative memory networks, and the hippocampus and other temporal lobe structures often are involved. These memory disorders may be temporary (e.g., after a seizure) or permanent (e.g., after severe head injury or in Alzheimer disease [AD]). There may be only the memory disorder, or the memory disorder may be associated with other cognitive disorders. Global amnesia is a combination of anterograde and retrograde amnesia and involves the hippocampus. Transient global amnesia has a sudden onset, lasts less than 24 hours, and occurs in the absence of other neurological signs or symptoms. The causal mechanisms are not clear, but it can be associated with migraine headache, vagal stimulation, and cerebrovascular ischemia.18Permanent global amnesia is rare and associated with damage to the hippocampus.19Domain–specific declarative memory loss can manifest as agnosias (agnosias are in the section on Data Processing Deficits).

Image processing is a higher level of memory function and includes the ability to use sensory data and language to form concepts, assign meaning, and make abstractions. Alterations in image processing include an inability to form concepts and generalizations or to reason. Thinking is very concrete. These memory disorders may be temporary (e.g., after a seizure or postconcussive states) or permanent (e.g., after severe head injury, severe stroke, or in AD). There may be only the memory disorder, or the memory disorder may be associated with other cognitive disorders.

The prefrontal areas mediate several cognitive functions, called executive attention functions (planning, problem solving, goal setting). The vigilance system provides the person with the ability to maintain a sustained state of alertness or concentration for searching and scanning activities and involves the right frontal areas and the locus ceruleus (LC) (located in the rostral pons) (see Fig. 17.7). Through the neurotransmitter norepinephrine from the LC, the speed of the orienting (selective attention) network is increased, and the detection function of the anterior cingulate gyrus (see Fig. 17.10) is decreased.

Detection is the recognition of the object's identity and the realization that the object fulfills a desired goal (e.g., target selection among competing, complex contingencies). There is conscious execution of an instruction, ensuring that the instructions are followed. The anterior cingulate cortex inhibits automatic responses so that a less routine response can be given. The basal ganglia and cingulate, as well as other frontal areas, function in color, motion, and form detection.

The anterior cingulate plus the ventrolateral and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (see Fig. 17.10) are involved in the representations of information in the absence of a stimulus, such as spatial position of visual events in memory when the event is removed from view. Working memory (short-term or recent memory) gives the person control over information processing (see Fig. 17.7). These temporary storage areas permit the brain to maintain or discard a limited amount of information (e.g., to retrieve instructions, such as strings or patterns of words or colors) and other information (e.g., strings of digits) needed to maintain a current stream of thought, resist distraction, and perform an immediate task. When attention is diverted, long-term memory is required to complete the task.168

Isolated (pure) vigilance deficit, detection deficit, and working memory deficits are uncommon and involve focal lesions of the prefrontal cortex. Whether these losses are temporary or permanent depends on the cause and severity of injury.20,21

Executive attention deficits include the inability to maintain sustained attention and a working memory deficit. Sustained attention deficit is an inability to plan, set goals, and recognize when an object meets a goal. A working memory deficit is an inability to focus and remember instructions and information needed to guide behavior and complete a single task. Executive attention deficits may be temporary, progressive, or permanent.22

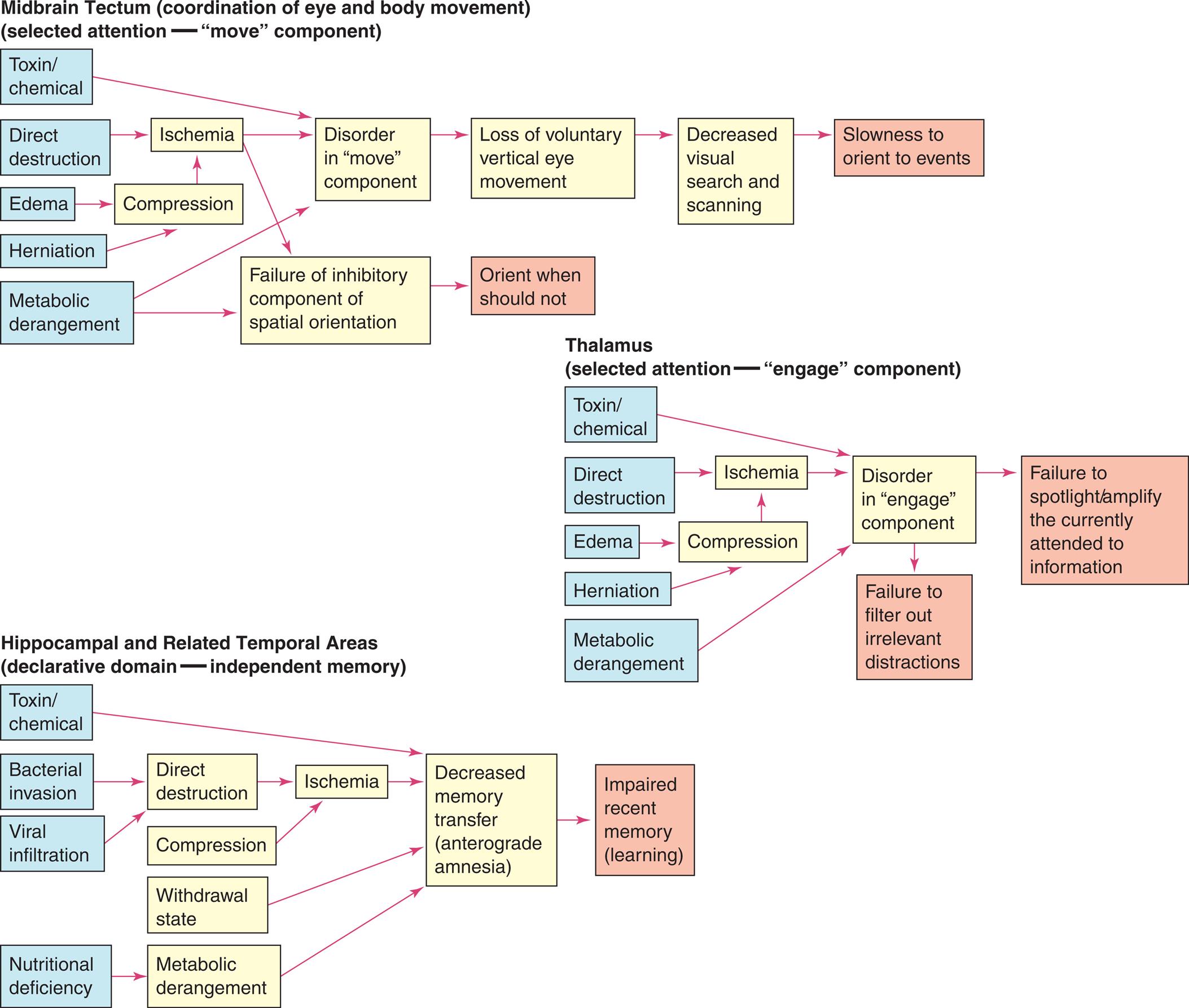

Pathophysiology

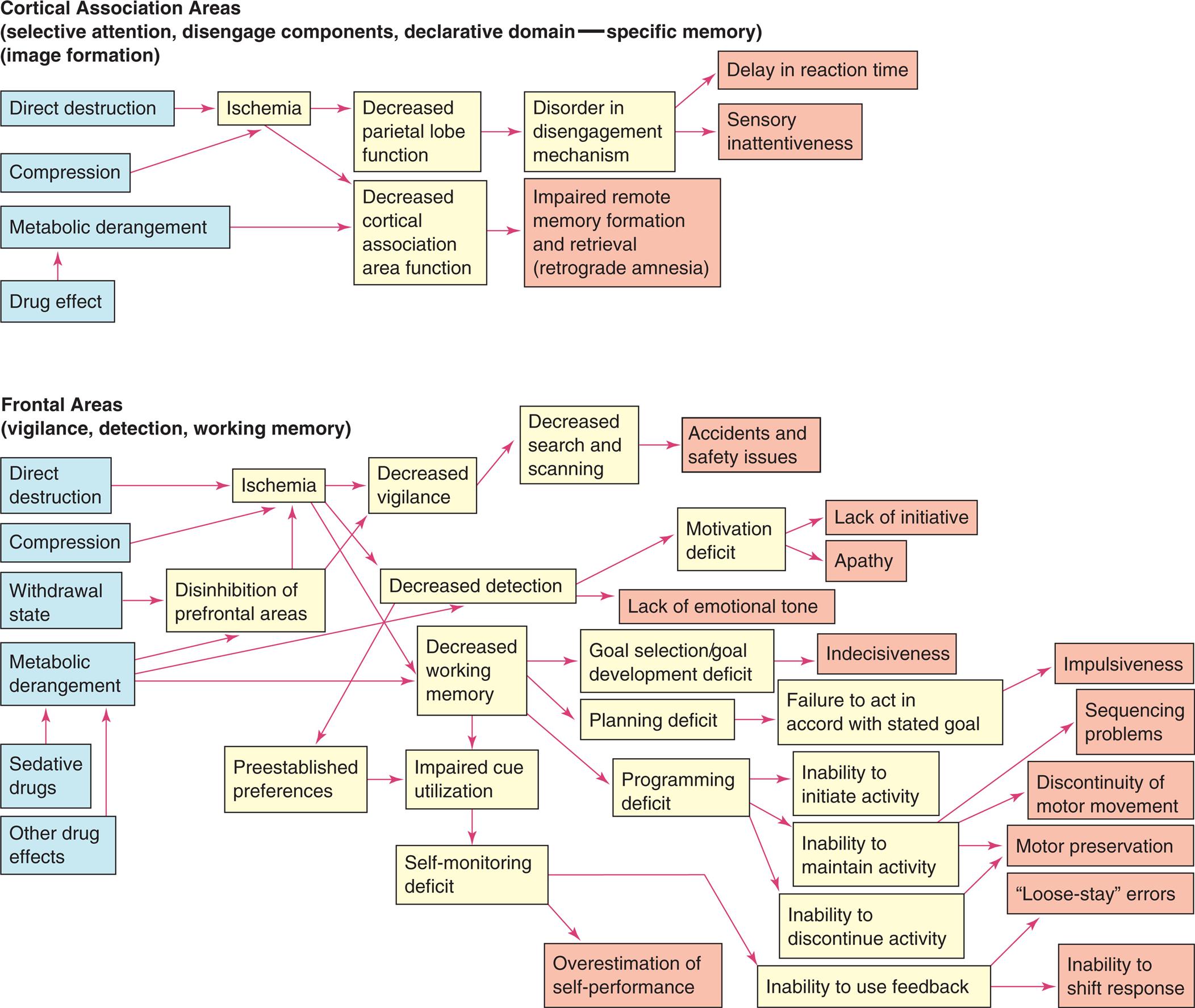

Very generally, the primary pathophysiologic mechanisms that operate in disorders of awareness are (1) direct destruction because of ischemia and hypoxia or indirect destruction because of compression and (2) the effects of toxins, inflammation, and chemicals, or metabolic derangement, including processes related to dementia. The pathophysiologic processes are summarized in Fig. 17.11.

Three flowcharts show cognitive network deficits. Top panel, midbrain tectum (coordination of eye and body movement) (selected attention -move component). The pathways in the flowchart are as follows. 1. Toxin or chemical. Leads to 8. 2. Direct destruction. Leads to 6. 3. Edema. Leads to 7. 4. Herniation. Leads to 7. 5. Metabolic derangement. Leads to 8. 6. Ischemia. Leads to 8. 7. Compression. 8. Disorder in move component. Leads to 10. 9. Failure of inhibitory component of spatial orientation. Leads to 11. 10. Loss of voluntary vertical eye movement. Leads to 12. 11. Orient when should not. 12. Decreased visual search and scanning. Leads to 13. 13. Slowness to orient to events. Middle panel, thalamus (selected attention-engage component). The pathways in the flowchart are as follows. 1. Toxin or chemical. Leads to 8. 2. Direct destruction. Leads to 6. 3. Edema. Leads to 7. 4. Herniation. Leads to 7. 5. Metabolic derangement. Leads to 8. 6. Ischemia. Leads to 8. 7. Compression. 8. Disorder in engage component. Leads to 9 and 10. 9. Failure to spotlight or amplify the currently attended to information. 10. Failure to filter out irrelevant distractions. Bottom panel, hippocampal and related temporal areas (declarative domain-independent memory). The pathways in the flowchart are as follows. 1. Toxin or chemical. Leads to 10. 2. Bacterial invasion. Leads to 5. 3. Viral infiltration. Leads to 5. 4. Nutritional deficiency. Leads to 8. 5. irect destruction. Leads to 9. 6. Compression. Leads to 9. 7. Withdrawal state. Leads to 10. 8. Metabolic derangement. Leads to 10. 9. Ischemia. Leads to 10. 10. Decreased memory transfer (anterograde amnesia). Leads to 11. 11. Impaired recent memory (learning). Two flowcharts show cognitive network deficits. Top panel, cortical association areas (selective attention, disengage components, declarative domain-specific memory). The pathways in the flowchart are as follows. 1. Direct destruction. Leads to 5. 2. Compression. Leads to 5. 3. Metabolic derangement. Leads to 7. 4. Drug effect. Leads to 3. 5. Ischemia. Leads to 6 and 7. 6. Decreased parietal lobe function. Leads to 8. 7. Decreased cortical association area function. Leads to 9. 8. Disorder disengagement mechanism. Leads to 10 and 11. 9. Impaired remote memory formation and retrieval (retrograde amnesia). 10. Delay in reaction time. 11. Sensory inattentiveness. Bottom panel, frontal areas (vigilance, detection, working memory). The pathways in the flowchart are as follows. 1. Direct destruction. Leads to 7. 2. Compression. Leads to 7. 3. Withdrawal state. Leads to 8. 4. Metabolic derangement. Leads to 8, 11, and 12. 5. Sedative drugs. Leads to 4. 6. Other drug effects. Leads to 4. 7. Ischemia. Leads to 10, 11, and 12. 8. Disinhibition of prefrontal areas. Leads to 10. 9. Preestablished preferences. Leads to 13. 10. Decreased vigilance. Leads to 15. 11. Decreased detection. Leads to 17 and 18. 12. Decreased working memory. Leads to 21, 22, and 23. 13. Impaired cue utilization. Leads to 14. 14. Self-monitoring deficit. Leads to 24. 15. Decreased search and scanning. Leads to 16. 16. Accidents and safety issues. 17. Motivation deficit. Lead to 18 and 19. 18. Lack of initiative. 19. Apathy. 20. Lack of emotional tone. 21. Goal selection or goal development deficit. Leads to 25. 22. Planning deficit. Leads to 26 and 30. 23. Programming deficit. Leads to 27, 28, and 29. 24. Overestimation of self-performance. 25. Indecisiveness. 26. Failure to act in accord with stated goal. Leads to 31. 27. Inability to initiate activity. 28. Inability to maintain activity. Leads to 32, 33, and 34. 29. Inability to discontinue activity. Leads to 34. 30. Inability to use feedback. Leads to 35 and 36. 31. Impulsiveness. 32. Sequencing problems. 33. Discontinuity of motor movement. 34. Motor preservation. 35. Loose-stay errors. 36. Inability to shift response.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of selective attention deficits, memory deficits, and executive attention function deficits are presented in Table 17.8.

Table 17.8

Evaluation and Treatment

Immediate medical management is directed at diagnosing the cause and treating reversible factors. Rehabilitative measures for cognitive system deficits generally are either compensatory or restorative in nature and have been greatly facilitated by computer technology and other electronic-assisted devices. Approaches based on behavioral techniques tend to be compensatory, whereas process-oriented approaches are restorative.

Selective attention and executive attention deficits masquerade as other cognitive deficits. Differential diagnosis of other cognitive deficits is blocked, and learning potential is largely obscured by the presence of an attention deficit. Therefore, diagnosis and treatment of attention deficits are fundamental.

Data Processing Deficits

Data processing deficits are problems associated with recognizing and processing sensory information and include agnosia, aphasia, and acute confusional states (ACSs).

Agnosia

Agnosia is a defect of pattern recognition—a failure to recognize the form and nature of objects by one or more of the senses. Agnosia can be tactile, visual, or auditory. For example, an individual may be unable to identify a safety pin by touching it with a hand but able to name it when looking at it. Agnosia may be as minimal as a finger agnosia (failure to identify by name the fingers of one's hand) or more extensive, such as a color agnosia.

Agnosia is produced by damage to the primary sensory area or in the interpretive areas of the cerebral cortex (parietal, temporo-occipital areas—Broca area and Wernicke area) (see Fig. 17.9). The symptoms of agnosia vary according to the location of the damage. The types of agnosia and the associated areas most involved with each are presented in Table 17.9. Although agnosia is commonly associated with cerebrovascular accidents, it may arise from any pathologic process that injures these specific areas of the brain (e.g., encephalitis, tumors, PD, trauma, or toxins).23

Table 17.9

Aphasia

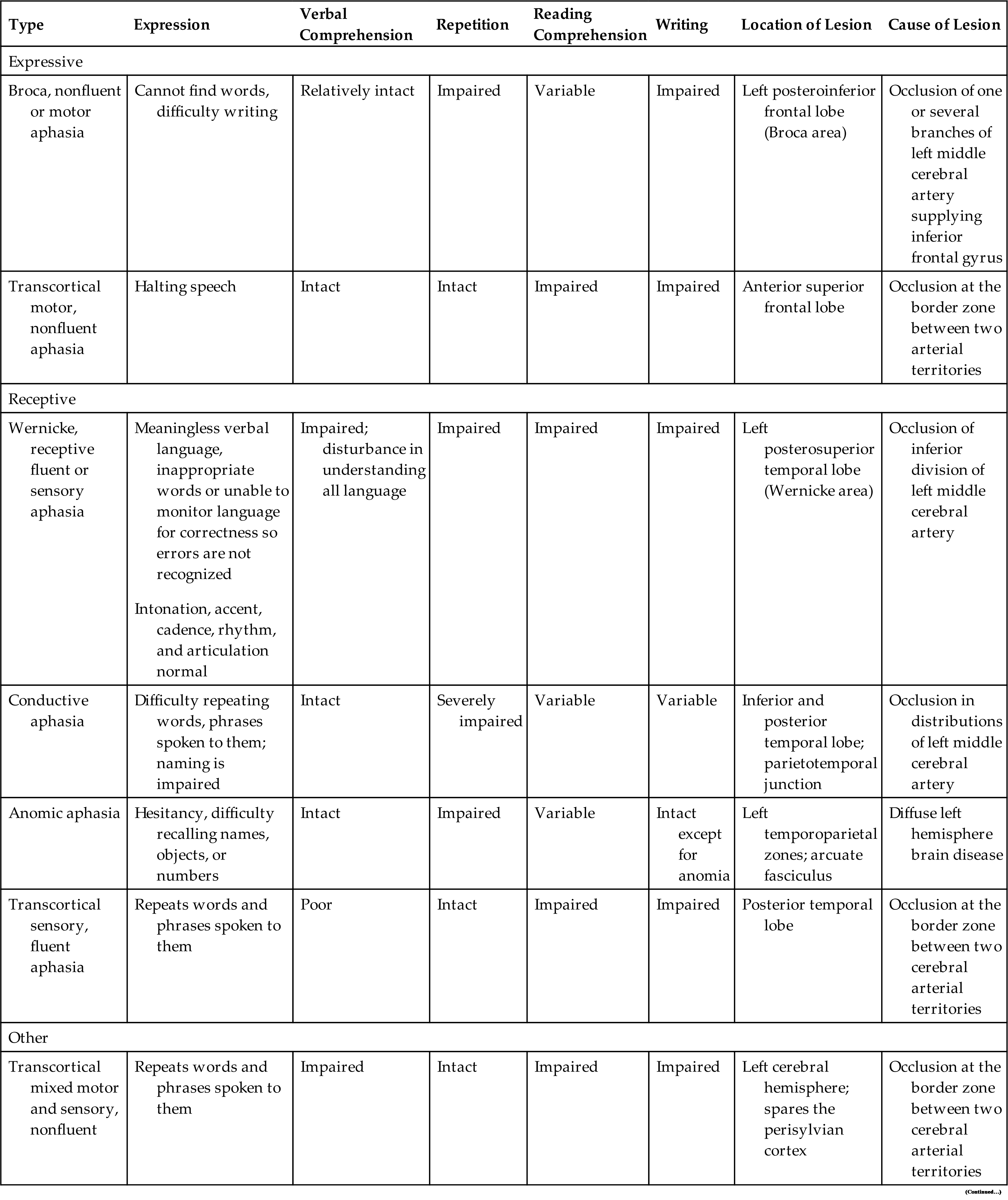

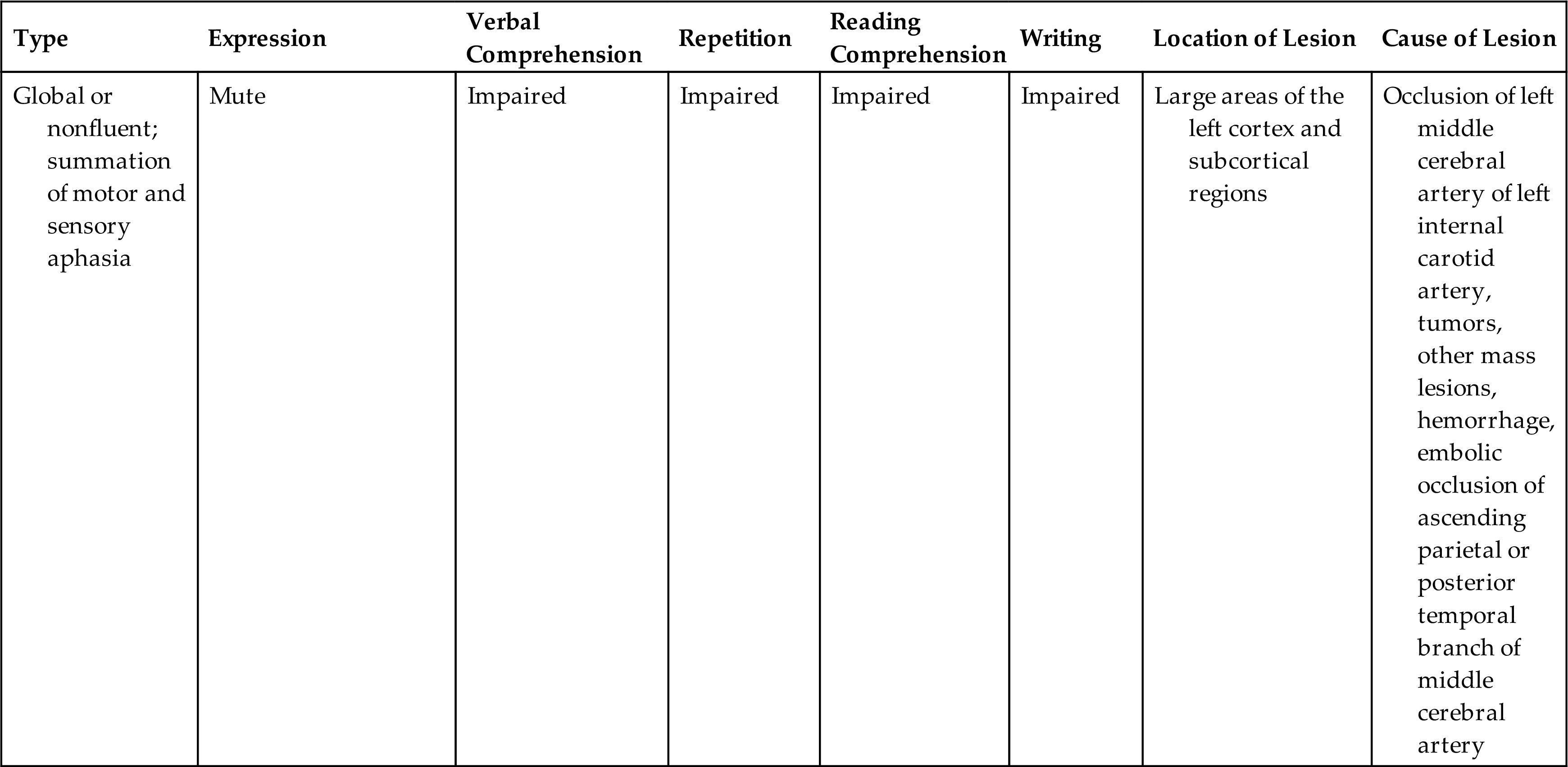

Aphasia is typically an acquired impairment of comprehension or production of language with impaired written or verbal communication. The terms aphasia and dysphasia are often used interchangeably; the term aphasia is used here.24 Aphasia results from dysfunction in the left cerebral hemisphere (e.g., Broca area [inferior frontal gyrus] and Wernicke area [superior temporal gyrus]) and the subcortical and cortical connecting networks (see Fig. 15.8B and C). Aphasias are commonly associated with a cerebrovascular accident involving the middle cerebral artery or one of its many branches (see Fig. 15.21). Language disorders, however, may arise from a variety of injuries and diseases, including vascular, neoplastic, traumatic, degenerative, metabolic, or infectious causes. Most language disorders result from acute processes or a chronic residual deficit of the acute process.

Aphasias have been classified anatomically (e.g., Wernicke or Broca area aphasias) or functionally as disorders of fluency (quality and content of speech). Aphasia associated with the frontal lobe, also known as Broca or motor aphasia, involves loss of ability to produce spoken or written language with slow or difficult speech. The speech that is produced is dysfluent and agrammatic. Verbal comprehension is usually present. Aphasia is differentiated from dysarthria, in which words cannot be articulated clearly because of cranial nerve damage or muscle impairment. Aphasia that is known as Wernicke or sensory involves an inability to understand written or spoken language. Speech is fluent, flowing at a normal rate, but words and phrases have no meaning (fluent dysphasia). Language deficits can be comprehensive; motor language deficits can be accompanied by deficits in comprehension, and comprehension deficits can be accompanied by motor deficits in language. For this reason, it can be misleading to classify aphasia as being expressive or receptive.25

Anomic aphasia is a sensory aphasia distinguished by difficulty finding words and naming a person or object. It is the most common symptom of cerebrovascular-related aphasia. Circumlocution, or describing an object as a way of trying to name something, is common in anomic aphasia. Auditory comprehension is present in conductive aphasia, but there is impaired verbatim repetition. Naming also can be impaired. The person recognizes the errors and tries to correct them. Speech is fluent, but words and sounds may be transposed. Damage is typically in the left hemisphere to networks that connect Broca and Wernicke areas. Anomic aphasias can also result from AD and other neurodegenerative diseases. Transcortical aphasias are rare and can be motor, sensory, or mixed. They involve areas of the brain that connect to the language centers. Anomic aphasia resulting from right hemisphere damage is rare as well.

Global aphasia is the most severe aphasia and involves both motor and sensory aphasia. The individual is non-fluent or mute; cannot read or write; and has impaired comprehension, naming, reading, and writing. Global aphasia is usually associated with a cerebrovascular accident involving the middle cerebral artery. Table 17.10 compares types of aphasia, and Table 17.11 illustrates some of the language disturbances. Pure aphasias are rare and are often mixed, making diagnosis difficult. Most types of aphasia improve with speech rehabilitation; however, if the cause is progressive disease (e.g., AD), improvement is not expected. Maintenance and quality of life are typically the treatment goals for progressive disease.

Table 17.10

Table 17.11

From Boss BJ. Dysphasia, dyspraxia, and dysarthria: Distinguishing features, Part I. Journal of Neurosurgical Nursing, 1984;16(3):151–160.

Acute Confusional States

Delirium (also known as acute confusional states or acute organic brain syndromes) are disorders of awareness, may be transient (acute) or persistent (chronic), and have either a sudden or a gradual onset. Delirium can be considered as a type of ACS, but for this discussion, ACSs, acute organic brain syndrome, and delirium are synonymous. Hospitalized older individuals are at greatest risk for delirium.26,27

Pathophysiology

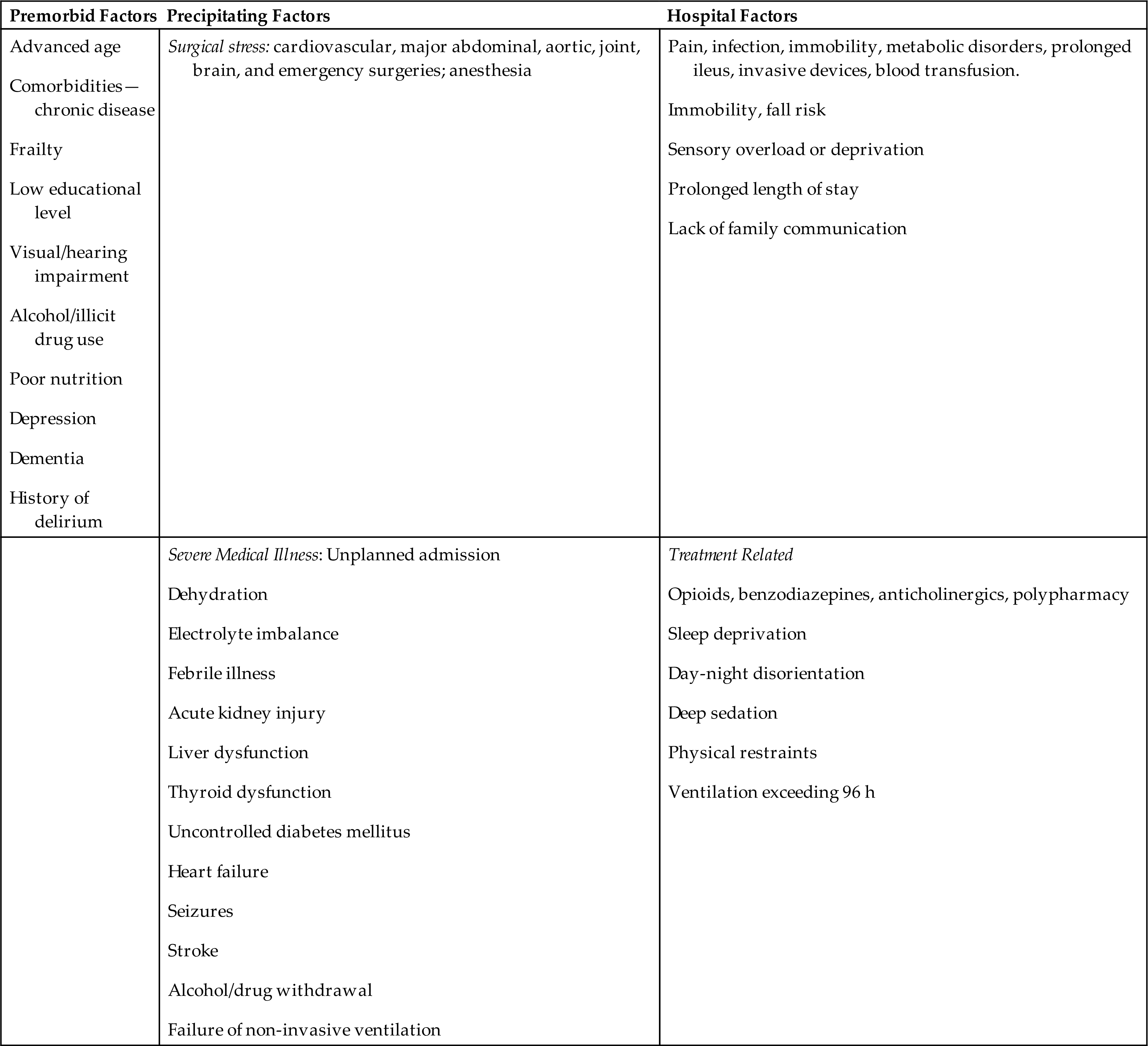

Delirium or ACSs arise from disruption of a widely distributed neural network (see Figs. 17.7 and 17.10) and involve alterations in cognitive function, emotion, perception, and consciousness. Delirium symptoms typically develop over hours to days. The pathogenesis of delirium is not well understood. Many risk factors are associated with delirium; they are summarized in Table 17.12. There does not seem to be a single mechanism to explain the sensory and processing dysfunction of the brain during delirium. The etiological factors leading to delirium appear to be an alteration in neurotransmitter availability and function, as well as a failure in the function of neuronal networks that integrate and process sensory information and motor response. The System Integration Failure Hypothesis (SIFH) connects the pathology of the network dysconnectivity and dysfunction. The hypothesis integrates five pathological precipitants of delirium (neuronal aging, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, neuroendocrine dysregulation, and circadian dysregulation) and proposes that all these factors are linked and have a role in causing delirium.28

Table 17.12

| Premorbid Factors | Precipitating Factors | Hospital Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical stress: cardiovascular, major abdominal, aortic, joint, brain, and emergency surgeries; anesthesia | ||

Data from Wilson JE, Mart MF, Cunningham C, et al. Delirium. Nature Reviews: Disease Primers, 2020;6(1):90; Bellelli G, Brathwaite JS, Mazzola P. Delirium: A marker of vulnerability in older people. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2021;13:626127.

Neuronal aging causes increased astrocyte and microglial activity, resulting in brain inflammation and neurodegenerative disease. Proinflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced, causing chronic inflammation. As part of the inflammatory process, leukocytes cause increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier, increasing edema and promoting neuronal apoptosis. The consequences are a lack of perfusion and brain ischemia.

Chronic inflammatory processes go on to produce oxidative stress. Oxidative stress causes damage to the brain by the formation of ROS. ROS damages myelin sheaths and increases injury to cerebral tissues. This can lead to cognitive decline and potentially irreversible or persistent delirium. Oxidative stress can also cause a failure in oxidative metabolism, which leads to failure of ionic pumps and thus an alteration in the release of neurotransmitters (e.g., glutamate, dopamine, acetylcholine, serotonin, and gamma-aminobutyric acid).

Physiological stress may result in neuroendocrine dysfunction. Continued stressors can cause high glucocorticoid levels. Chronic sleep deprivation, or circadian rhythm dysregulation, is considered a physiological stressor, which increases proinflammatory cytokines and cortisol levels, leading to cognitive alterations and delirium. With increased and prolonged exposure, glucocorticoids may affect neuronal function and cause neuronal injury and death.

Most metabolic disturbances (e.g., hypoglycemia, thyroid disorders, liver, or kidney disease) that produce delirium interfere with neuronal metabolism or synaptic transmission. Many drugs and toxins also interfere with neurotransmission function at the synapse.

Clinical Manifestations

There are four different types of delirium: hyperactive, hypoactive, mixed, and terminal. Delirium causes deficits in five different areas of brain function: cognitive deficits, attentional deficits, circadian rhythm dysfunction, emotional dysregulation, and psychomotor dysregulation. Hyperactive delirium manifests as restlessness, irritability, insomnia, tremulousness, hallucinations, or delusions. In a fully developed delirium state, the individual is completely inattentive, and perceptions are grossly altered, with extensive misperception and misinterpretation. The person appears distressed and often perplexed; conversation is incoherent. Frank tremor and high levels of restless movement are common. Violent behavior may be present. The individual cannot sleep, is flushed, and has dilated pupils, a rapid pulse rate (tachycardia), elevated temperature, and profuse sweating (diaphoresis).

Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS), also known as agitated delirium, is a type of hyperactive delirium that can lead to sudden death. Its symptoms include altered mental status, combativeness, aggressiveness, tolerance to significant pain, rapid breathing, sweating, severe agitation, elevated temperature, noncompliance, or poor awareness of direction from police or medical personnel, inability to become fatigued, unusual or superhuman strength, and inappropriate clothing for the current environment. Hypoglycemia, thyroid storm, certain kinds of seizures, cocaine, methamphetamine intoxication, and/or catecholamine-induced fatal arrhythmias are associated with ExDS.29

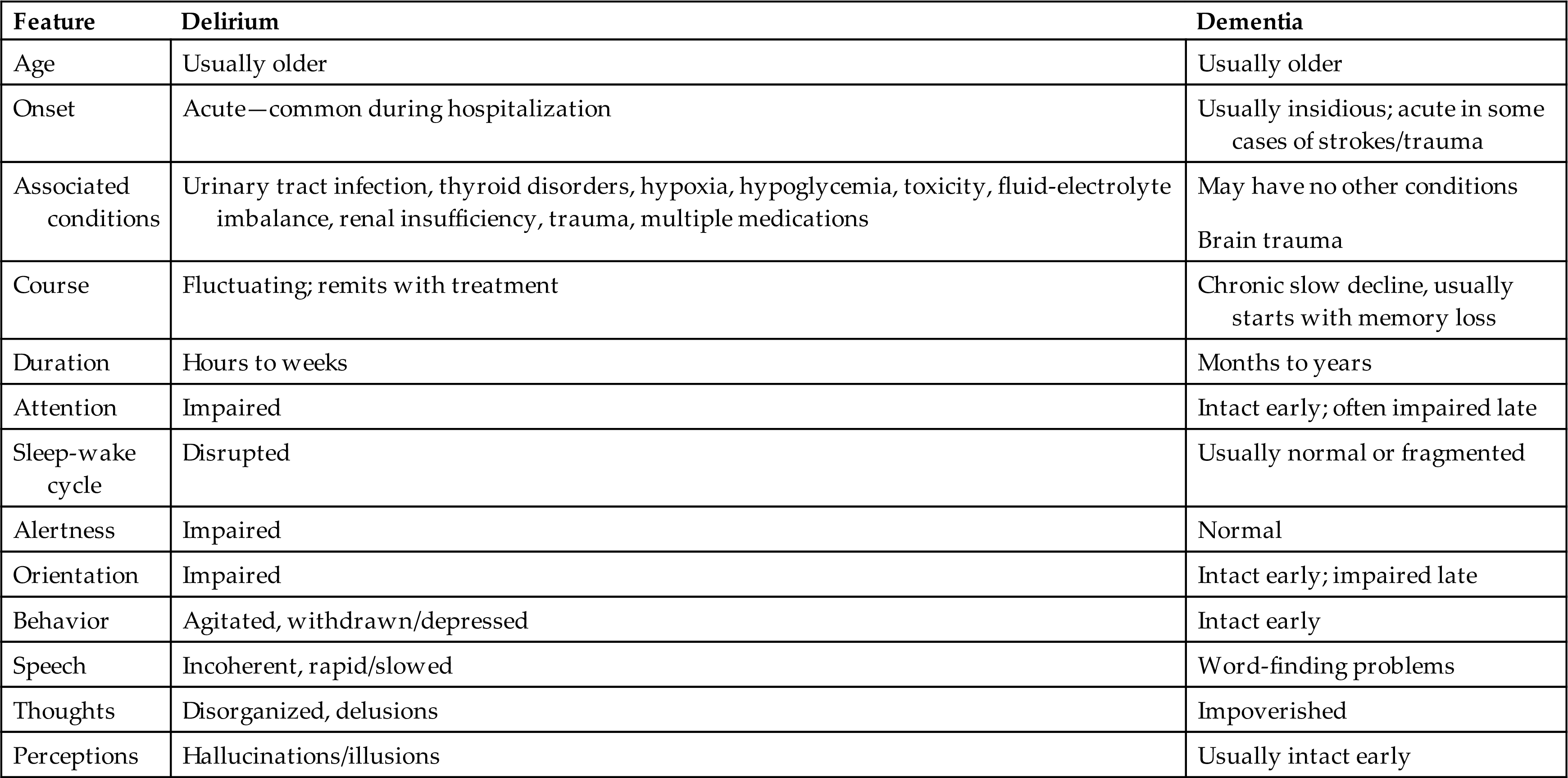

Hypoactive delirium is the most common form of delirium. It is associated with underactivity and may occur in individuals who have fevers or metabolic disorders (e.g., chronic liver or kidney failure), are under the influence of CNS depressants or are postoperative. The individual exhibits decreased mental function, specifically alertness, attention span, accurate perception, interpretation of the environment, and reaction to the environment. Forgetfulness, confusion, and apathy are prominent; speech may be slow, and the individual dozes frequently. Hypoactive delirium can be mistaken for depression or dementia, including AD (Table 17.13). It has the highest rate of mortality, as it is often undiagnosed, and treatment is delayed.30

Table 17.13

Adapted from Caplan JP, Rabinowitz T. An approach to the patient with cognitive impairment: Delirium and dementia. Medical Clinics of North America, 2010;94(6):1103–1116, ix.

Mixed delirium is a combination of both hyperactive and hypoactive delirium, fluctuating from one to the other. Delirium resolves suddenly or gradually in 2 to 3 days, although delirium states occasionally persist for weeks.

Terminal delirium, also known as terminal restlessness or terminal agitation, is often seen in individuals during the final stages of dying. Metabolic dysfunction, common at the end of life as organs shut down, and neurotransmitter abnormalities are thought to be a major cause. Onset is often preceded by physical, emotional, or spiritual distress, anxiety, restlessness, and agitation. Hallucinations may also be seen (e.g., talking to someone who is not present). Terminal delirium is not reversible, but symptoms may come and go during the actively dying period. It is important to rule out all other causes of delirium prior to a diagnosis of terminal delirium.31,32

Evaluation and Treatment

An ACS is an acute medical problem. The initial goal is to establish that the individual’s confusion arises from delirium and to identify the cause and contributing factors. Hypoactive delirium will need to be differentiated from depression or an underlying dementia. A complete history and physical examination, as well as laboratory tests including an electrocardiogram and bloodwork, urine, cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), and imaging studies are needed. Several assessment scales are available to guide evaluation.33–35

Once the cause is established, treatment is directed at addressing the underlying condition. Delirium can be preventable and reversible in some individuals with management of risk factors and early intervention. Assessing pain management, hydration, nutrition, sleep maintenance, hygiene, and toileting may prevent or treat the delirium. Drugs that may be contributing to or causing the condition are discontinued unless the problem is the result of drug withdrawal. Nonpharmacologic measures should be utilized initially to treat the delirium. Measures such as turning the lights low, minimizing noise, playing soothing music, and orientation to surroundings may reduce agitation and anxiety. If the individual is agitated, verbal de-escalation techniques and validating their reality instead of trying to reorient them may help to decrease their agitation and promote a feeling of calmness.

Pharmacologic (i.e., antipsychotics) interventions may be implemented once the underlying cause of delirium has been determined and all reversible causes have been ruled out. Typically, this route is only for individuals who display agitated forms of delirium. Though there is no approved medication for delirium, drugs such as risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and haloperidol can be used with caution. If these pharmacological measures are used, initial drug doses should be low and slowly titrated up.36 If the individual has terminal delirium with severe refractory agitation, palliative sedation may be considered.37

Dementia

Dementia is an acquired deterioration and a progressive failure of many cerebral functions that includes impairment of intellectual processes with decreasing abilities in the areas of orientation, memory, language, judgment, and decision making. Because of declining intellectual ability, the individual may exhibit alterations in behavior, for example, agitation, wandering, and aggression.38

Dementias can be classified according to etiologic factors (e.g., genetics, trauma, tumors, vascular disorders, infections) and to associated clinical and laboratory signs. Dementing processes also have been grouped as cortical, subcortical, or both. Box 17.2 lists the potentially reversible and irreversible causes of dementia. AD is the most common cause followed by vascular dementia, then dementia with Lewy bodies (i.e., Parkinsonian dementia [see section on PD]), and FTD. Parkinsonian and Lewy body (intracellular inclusions with high concentrations and abnormal folding of alpha-synuclein and other proteins) dementia can be difficult to diagnose, and AD and vascular disease can appear concurrently. When different types of dementia occur concurrently, it is classified as a mixed dementia.39 In people younger than 60 years, FTD rivals AD in terms of frequency.40

Pathophysiology

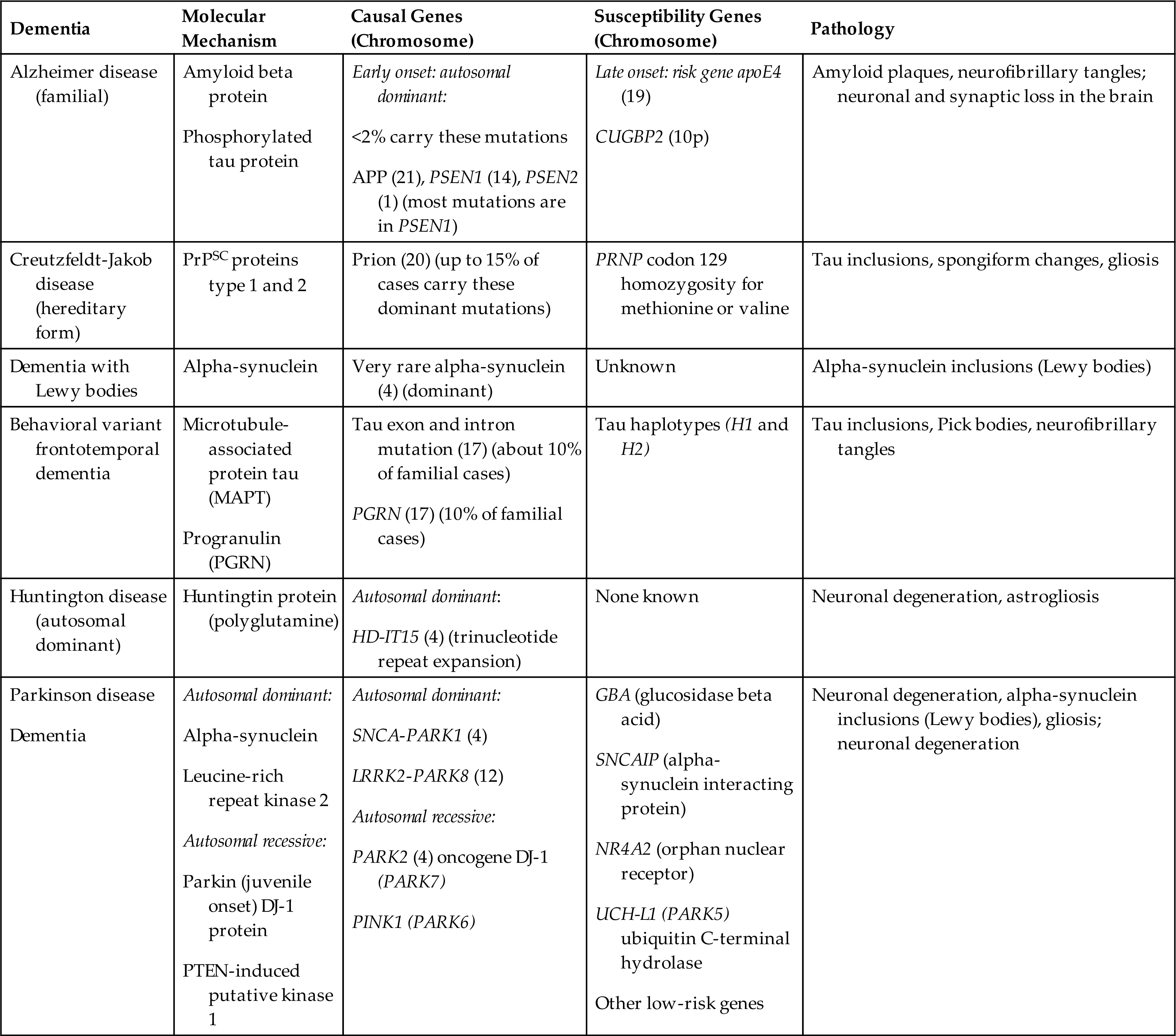

Mechanisms leading to dementia include neuron degeneration, compression of brain tissue, atherosclerosis of cerebral vessels, and brain trauma. Genetic predisposition (Table 17.14) is associated with the neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, FTD, HD (see section on HD), and PDs (see section on PD) leading to abnormal protein accumulation within neurons and other vulnerable parts of the brain. CNS infections, including the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and prions in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) (see Table 17.14 and Box 17.3), also lead to nerve cell degeneration and brain atrophy. The neuropathology associated with HIV and HIV associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) is presented in Chapter 18.

Table 17.14

APP, Amyloid precursor protein; PRNP, pr ion protein; PrPSC, prion protein scrapie form; PSEN, presenilin; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog.

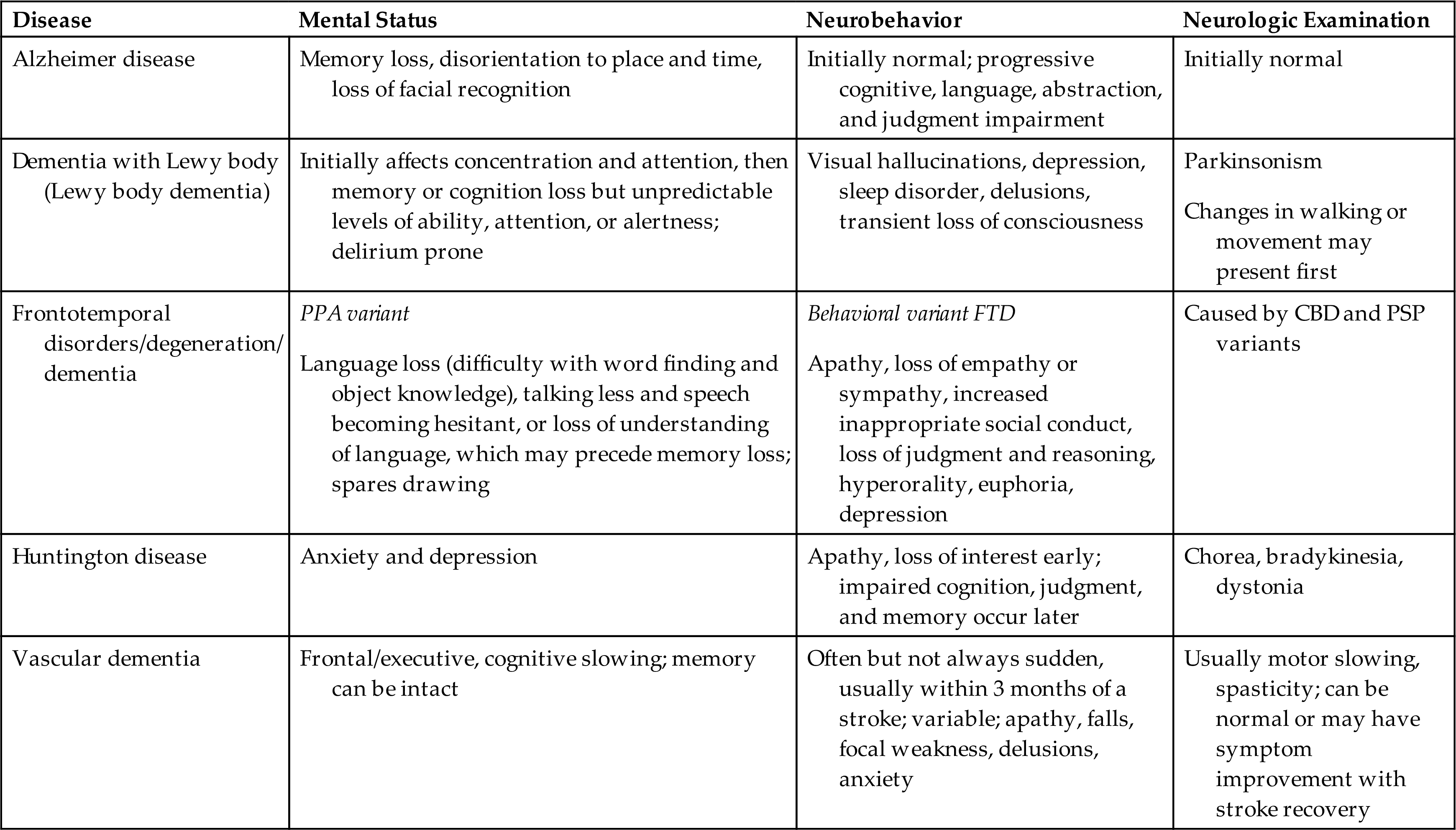

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of the major dementias are presented in Table 17.15.

Table 17.15

CBD, Corticobasal (cortex and basal ganglia) degeneration; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; PPA, primary progressive aphasia; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy.

Data from Bott NT, Radke A, Stephens ML, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: Diagnosis, deficits and management. Neurodegenerative Disease Management, 2014;4(6):439–454; Darrow MD. A practical approach to dementia in the outpatient primary care setting. Primary Care, 2015;42(2):195–204; Hugo J, Ganguli M. Dementia and cognitive impairment: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clinical Geriatric Medicine, 2014;30(3):421–442; Nordberg A. Dementia in 2014. Towards early diagnosis in Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews: Neurology, 2015;11(2):69–70.

Evaluation and Treatment

Establishing the cause of dementia may be complicated, and individuals with clinical manifestations of dementia should be evaluated with laboratory and neuropsychologic testing to identify underlying conditions that may be treatable. Controlling associated risk factors such as head injury, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, smoking, air pollution, and exposure to environmental toxins, as well as treating depression and avoiding excessive alcohol intake, may cause less neuronal damage and help to prevent dementia.

Increasing or maintaining cognitive reserve (brain resilience) is an important component of dementia prevention. Studies have found that individuals with untreated hearing loss, lower levels of education, and social isolation have a higher risk of dementia. Treating hearing loss, staying mentally active, and having a social network are also ways to reduce the risk of dementia. Individuals with dementia are known to go through an initial stage called mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI causes cognitive changes that can be noticed, but these changes are not serious enough to affect activities of daily living. Though individuals with MCI are at higher risk for dementia, not everyone with MCI progresses to dementia.41–43 Unfortunately, no specific cure exists for most progressive dementias. Therapy is directed at maintaining and maximizing use of the remaining capacities, restoring functions if possible, and accommodating to lost abilities. Educating the family and caregivers on the progressive nature of the disease process and ways to assist the individual physically and mentally is essential.

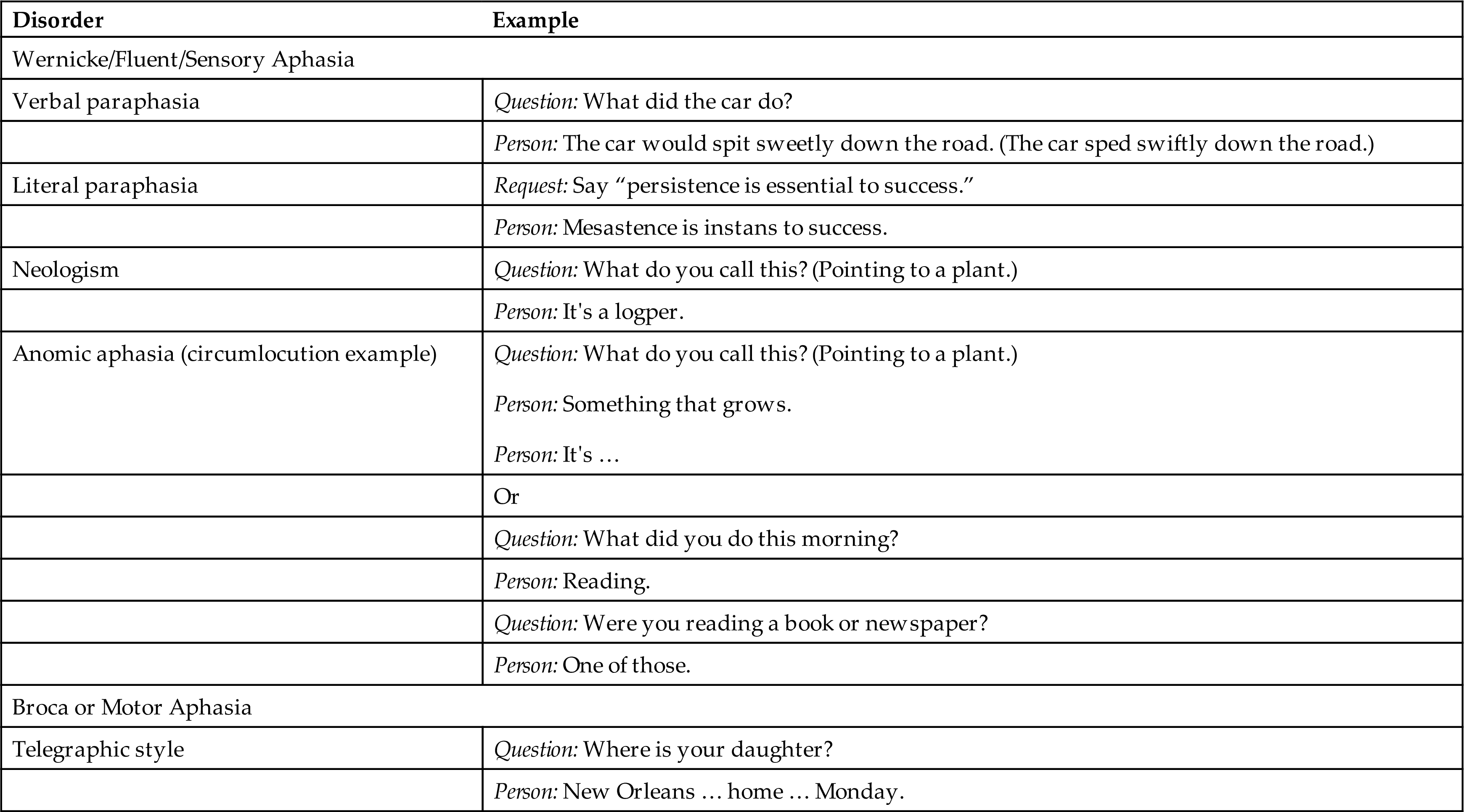

Alzheimer disease

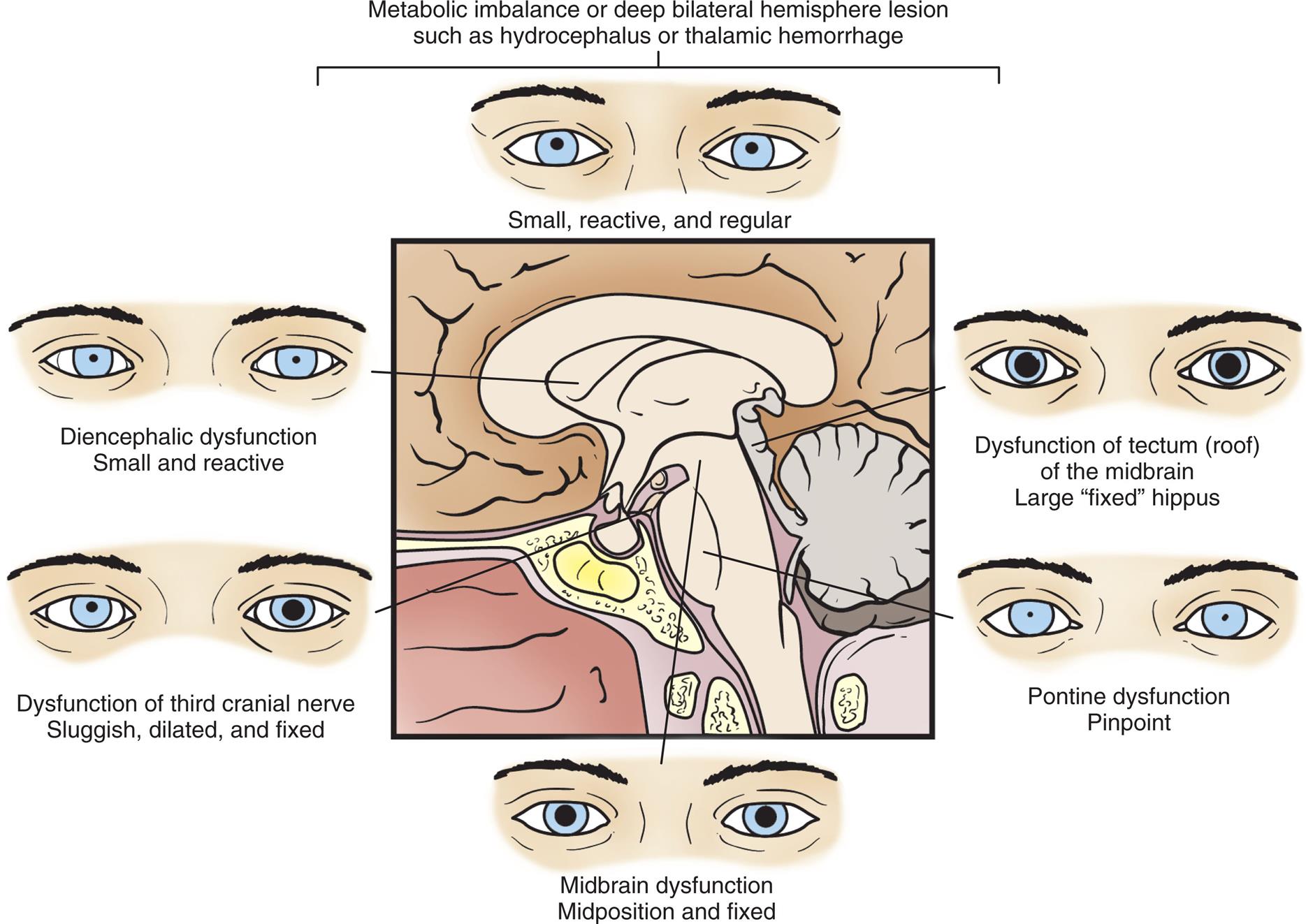

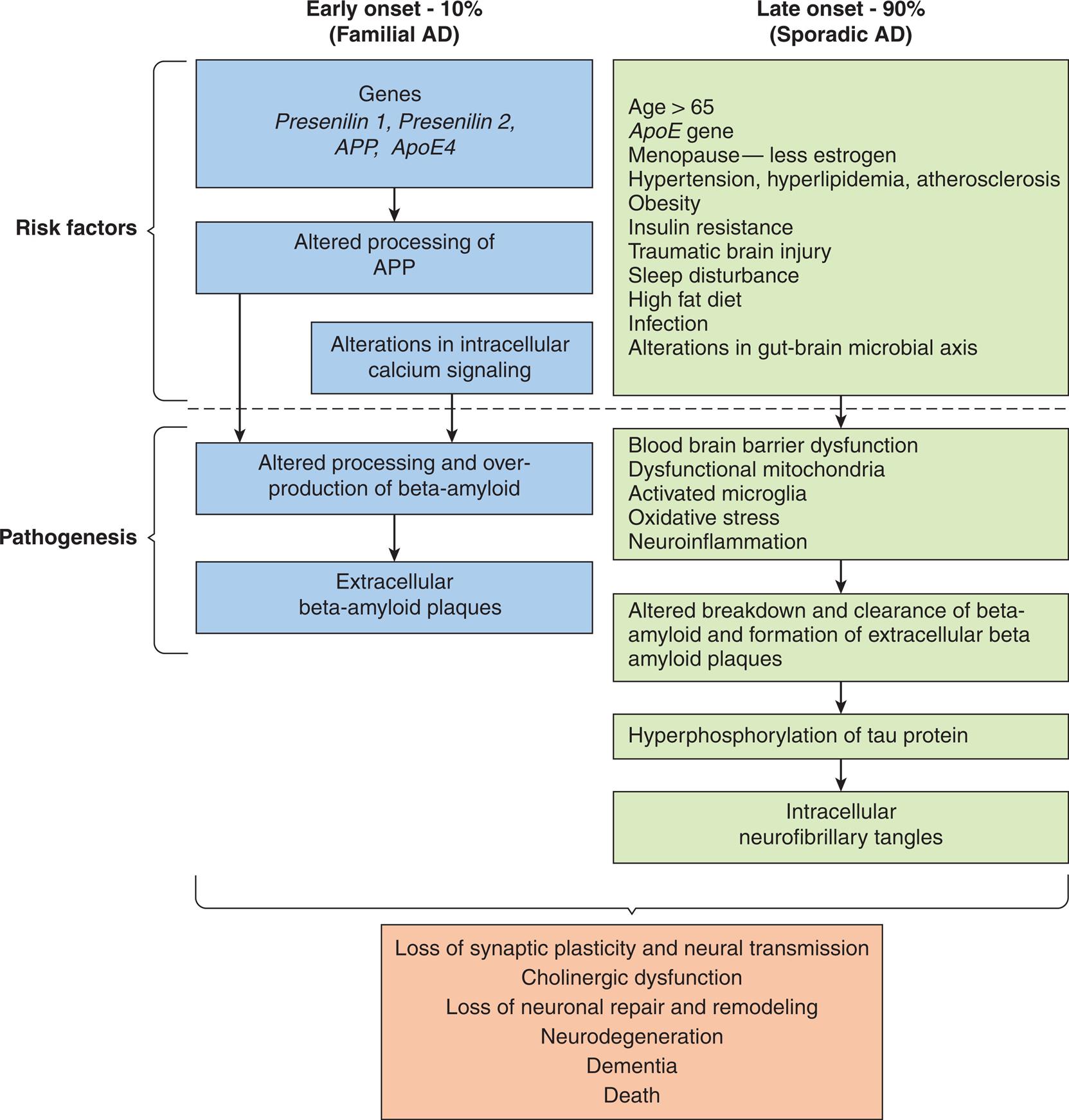

AD also known as Alzheimer type dementia (ATD) is the leading cause of severe cognitive and behavioral dysfunction in older adults. An estimated 6.2 million Americans have AD, and two-thirds of these individuals are women.44 However, the estimated number of Americans with dementia is thought to be much higher. Individuals with MCI are at a higher risk of developing AD. With better diagnostic tools, such as imaging and biomarkers, individuals with MCI related to AD will be included in the prevalence numbers. The greatest risk factors associated with AD are age and family history. Modifiable risk factors for dementia have been discussed previously (see previous section on Dementia). Fig. 17.12 summarizes the risk factors and pathogenesis of AD.

. AD, Alzheimer disease; ApoE, apolipoprotein E; APP, amyloid precursor protein. (Data from Ganguly U, Kaur U, Chakrabarti SS et al. Oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and nadph oxidase: Implications in the pathogenesis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2021;2021:7086512; Tini G, Scagliola R, Monacelli F et al. Alzheimer’s disease and cardiovascular disease: A particular association. Cardiology Research and Practice, 2020;2020:2617970; Knopman DS, Amieva H, Petersen RC et al. Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews: Disease Primers, 2021;7(1):33; Neuner SM, Tcw J, Goate AM. Genetic architecture of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Disease, 2020;143:104976; Edwards Iii GA, Gamez N, Escobedo G Jr, et al. Modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2019;11:146.)

Two flowcharts show the proposed factors and pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. The flowchart on the left shows data for early onset, 10 percent (familial A D). 1. Risk factors: Genes, presenilin 1, presenilin 2, A P P, A p o E 4. 2. Risk factors: Altered processing of A P P. 3. Risk factors: Alterations in intracellular calcium signaling. 4. Pathogenesis: Altered processing and over-production of beta-amyloid. 5. Pathogenesis: Extracellular beta-amyloid plaques. The flowchart on the right shows data for late onset, 90 percent (sporadic A D). 1. Risk factors: age greater than 65. A p E gene; menopause-less estrogen; hypertension, hyperlipidemia, atherosclerosis; obesity; insulin resistance; traumatic brain injury; sleep disturbance; high fat diet; infection; alterations in gut-brain microbial axis. 2. Pathogenesis: blood brain barrier dysfunction; dysfunctional mitochondria; activated microglia; oxidative stress; neuroinflammation. 3. Pathogenesis: altered breakdown and clearance of beta-amyloid and formation of extracellular beta amyloid plaques. 4. Hyperphosphorylation and tau protein. 5. Intracellular neurofibrillary tangles. Both types of onsets of the disease result in the following manifestations. • Loss of synaptic plasticity and neural transmission. • Cholinergic dysfunction. • Loss of neuronal repair and remodeling. • Neurodegeneration. • Dementia. • Death.

Pathophysiology

The exact cause of AD is unknown. However, studies are ongoing to classify the genetic variations. Genome-wide association studies have identified numerous single nucleotide variations for late-onset AD. Epigenetic mechanisms are associated with the pathology of AD, but the mechanisms are yet to be determined.

Early-onset AD (EOAD) accounts for 5% to 10% of cases of AD. Early-onset AD can be familial (FAD) or sporadic. The cause of sporadic EOAD is unknown. FAD represents about 10% to 15% of early-onset AD and is an autosomal dominant disease.45 FAD has been linked to three causal genes with mutations on chromosome 21, although the mechanism of how they cause disease is not clear. The mutations result in the dysregulation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing and leads to alterations of folding and concentration of the derived amyloid beta protein. The consequence is the formation of amyloid plaque in the brain. The three gene mutations are:

- 1. APP gene mutation—abnormal APP. Normally APP is a transmembrane protein; processing of APP generates amyloid beta-protein, which is important for synapse formation, synaptic plasticity, increased release of acetylcholine, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation, and memory formation. Mutations change the structure and result in accumulation of beta-amyloid.46,47

- 2. PSEN1 gene mutation (more common and found in more severe disease)—abnormal presenilin 1 protein (more than 200 mutations have been described)—PSEN 1 protein normally functions as a protease to cleave APP, generating amyloid-beta protein of varying lengths. Either loss or gain of function may alter amyloid beta production and accumulation and cause FAD.48

- 3. PSEN2 gene—abnormal presenilin 2 protein (19 reported mutations)—PSEN2 protein is also a protease that cleaves APP, and mutation leads to alterations in amyloid-beta structure and aggregation.

Apolipoprotein E gene-allele 4 (APOE4) on chromosome 19 is also found. APOE4 protein helps to carry cholesterol and other lipids in the bloodstream, and the gene mutation is associated with alterations in lipid metabolism and interference with amyloid-beta protein clearance from the brain. The amyloid-beta protein is processed into neurotoxic fragments found in the plaques in the brain of people with AD.49 Chromosome 21 is also involved in Down syndrome (Trisomy 21); as such, individuals with Down syndrome have a high incidence of EOAD. Many individuals with Down syndrome develop AD by age 40 and have clinical manifestations of the disease before age 65. EOAD has an atypical clinical presentation (headaches, seizures, hyperreflexia), a faster rate of deterioration, delayed diagnosis, and a higher mortality rate. Traumatic brain injury is a common risk factor for those with EOAD; however, other associated risks, such as diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, and obesity, are not as common.50

Sporadic late-onset AD is the most common type of AD and does not have a specific genetic association; however, the cellular pathology is the same as that for gene-associated early- and late-onset AD. The main genetic risk for late-onset AD is related to age and APO4E.51

Pathologic alterations in the brain in both early- and late-onset AD include accumulation of extracellular neuritic plaques containing a core of abnormally folded beta amyloid proteins, intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles consisting of hyper-phosphorylated tau proteins, and degeneration of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons with loss of acetylcholine. Failure to process and clear APP results in the accumulation of toxic fragments of amyloid-beta protein that leads to formation of diffuse neuritic plaques, disruption of nerve impulse transmission, and death of neurons. Amyloid-beta protein is also deposited in the smooth muscle of cerebral arteries, causing an amyloid angiopathy and chronic brain hypoperfusion, contributing to neurodegeneration. In some cases, differentiating AD from vascular dementia may be difficult (see next section) (Fig. 17.13).52 However, the role of amyloid-beta protein in the diagnosis of AD is controversial as individuals without clinical manifestations of dementia have amyloid-beta plaques like individuals with dementia and individuals with other neurodegenerative diseases. There is also a hypothesis that amyloid-beta proteins may play a protective role in herpes-induced AD. There are different forms of amyloid-beta proteins and it is not yet clear which forms are the most pathological and by what mechanism they cause dementia.53