Mechanisms of Hormonal Regulation

Karen C. Turner and Valentina L. Brashers

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Rogers/pathophysiology/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Rogers/pathophysiology/

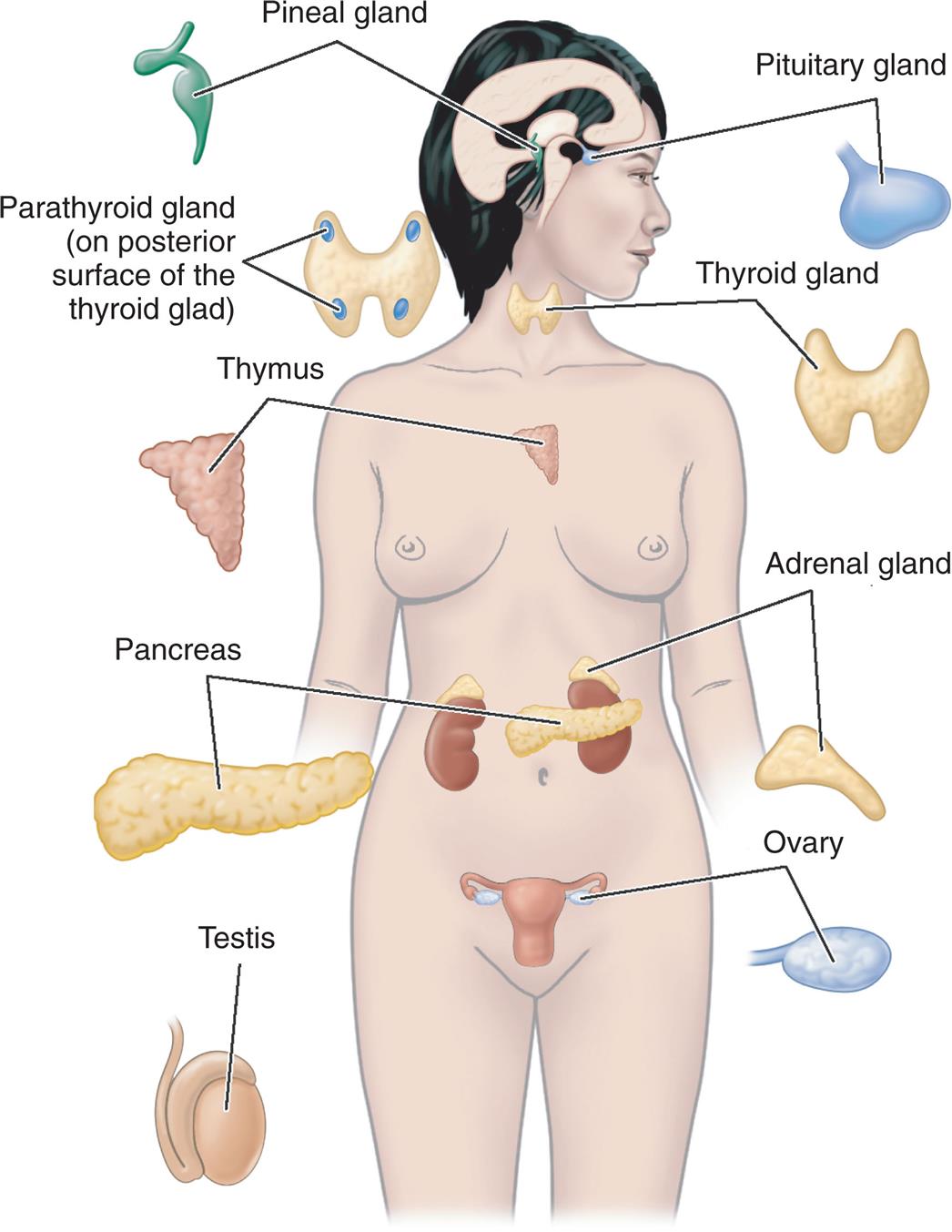

The endocrine system is composed of various glands located throughout the body (Fig. 21.1). These glands can synthesize and release special chemical messengers called hormones. The endocrine, nervous, and immune systems work together to regulate responses to internal and external environments. The endocrine system has five general functions: (1) differentiation of the reproductive and central nervous systems in the developing fetus; (2) stimulation of sequential growth and development during childhood and adolescence; (3) coordination of the male and female reproductive systems, which makes sexual reproduction possible; (4) maintenance of an optimal internal environment throughout life; and (5) initiation of corrective and adaptive responses when emergency demands occur. Hormones convey specific regulatory information among cells and organs and are integrated with the nervous system to maintain communication and control. The mechanisms of communication and control occur within a cell (autocrine), between local cells (paracrine), and between cells located remotely from each other (endocrine).

An illustration of a human figure identifies and labels the following major endocrine glands, from the top to the bottom: pineal gland, pituitary gland, thyroid gland, parathyroid gland (on posterior surface of the thyroid gland), thymus, adrenal gland, pancreas, ovary, and testis.

Mechanisms of Hormonal Regulation

Endocrine glands respond to specific signals by synthesizing and releasing hormones into circulation, which then trigger intracellular responses. All hormones share certain general characteristics:

- 1. Hormones have specific rates and rhythms of secretion. Three basic patterns of secretion are (a) diurnal patterns, (b) pulsatile and cyclic patterns, and (c) patterns that depend on levels of circulating substrates (e.g., calcium, sodium, potassium, or the hormones themselves).

- 2. Hormones operate within feedback systems, either negative or positive, to maintain an optimal internal environment.

- 3. Hormones affect only target cells with specific receptors for the hormone and then act on these cells to initiate specific cell functions or activities.

- 4. Steroid hormones are either excreted directly by the kidneys or metabolized (conjugated) by the liver, which inactivates them and renders the hormone more water soluble for renal excretion. Peptide hormones are catabolized by circulating enzymes and eliminated in the feces or urine.

Hormones may be classified according to structure, gland of origin, effects, or chemical composition. (Table 21.1 categorizes known hormones based on structure.) The mechanisms of action and secretion of hormones represent an extremely complex system of integrated hormonal and neural responses.

Table 21.1

Regulation of Hormone Release

Hormones are released to respond to an altered cellular environment or to maintain the level of another hormone or substance. One or more of the following mechanisms regulates hormone release: (1) chemical factors (such as blood glucose or calcium levels), (2) endocrine factors (a hormone from one endocrine gland controlling another endocrine gland), and (3) neural control. For example, insulin is secreted by the (1) chemical stimulation of increased plasma glucose levels, (2) the hormone cortisol from the adrenal cortex, and (3) direct stimulation of the insulin-secreting cells of the pancreas by the autonomic nervous system, which is a form of neural control.

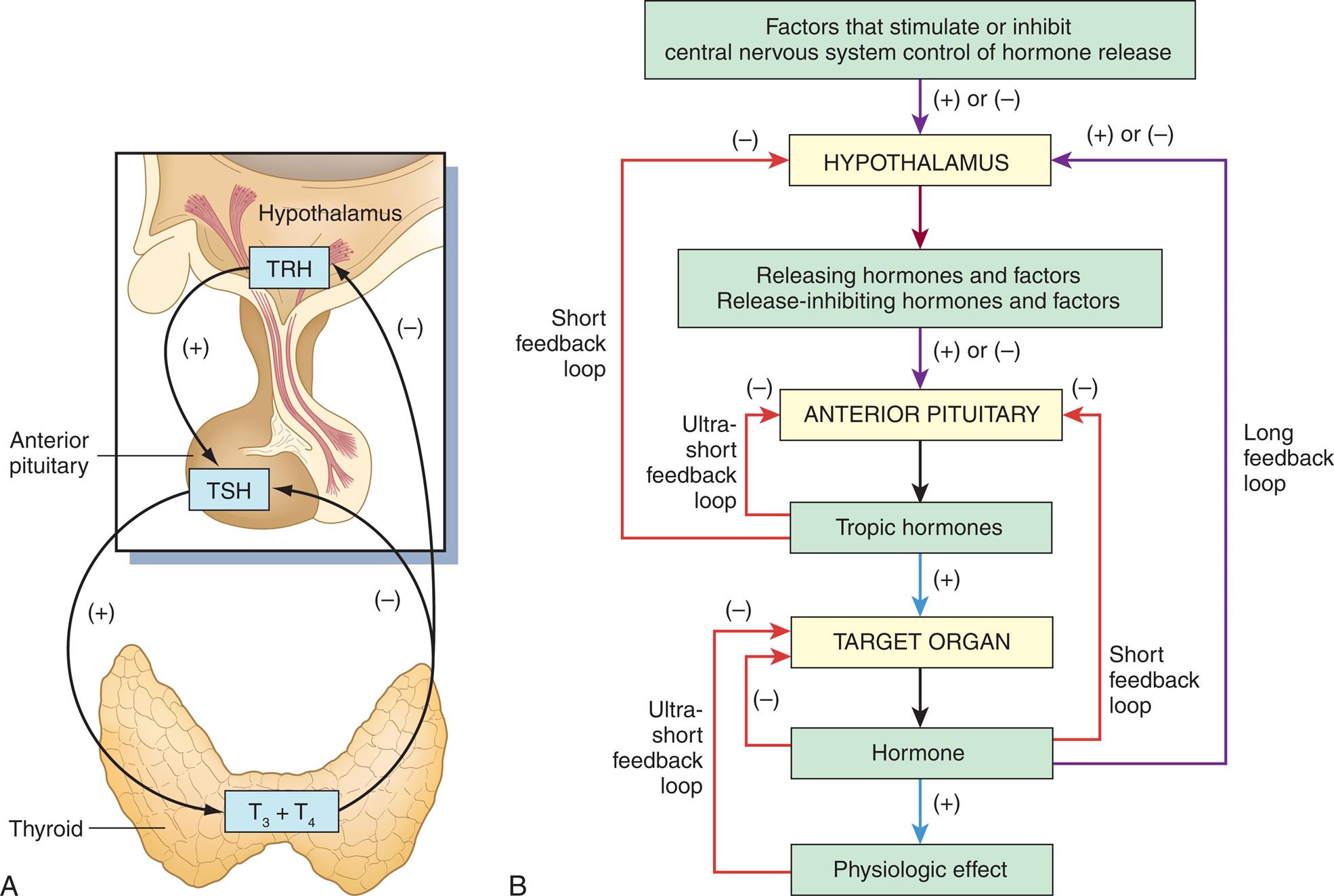

Feedback systems provide precise monitoring and control of the cellular environment. Both negative- and positive-feedback systems are important for maintaining hormone levels within physiologic ranges. Positive feedback occurs when a neural, chemical, or endocrine response increases the synthesis and secretion of a hormone. Negative feedback, which is more common, occurs when a changing chemical, neural, or endocrine response to a stimulus decreases the synthesis and secretion of a hormone. Fig. 21.2A illustrates both positive and negative feedback within the hypothalamus-pituitary axis and the thyroid gland. Positive feedback occurs when thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) is released from the hypothalamus in response to low thyroid hormone levels. TRH stimulates the secretion of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which then stimulates the synthesis and secretion of the thyroid hormones thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). Negative feedback occurs when increasing levels of T4 and T3 feedback on the pituitary and hypothalamus inhibit TRH and TSH synthesis and decrease the synthesis and production of thyroid hormones. Fig. 21.2B illustrates a more complex model for feedback mechanisms across the hormonal system. The lack of positive or negative feedback on hormonal release often results in pathologic changes in hormone production (see Chapter 22).

(A) Endocrine feedback loops for the thyroid gland: TRH, Thyroid-releasing hormone; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; T3, triiodothyronine; T4, tetraiodothyronine (thyroxine). (B) General model for feedback mechanisms in the regulation of hormone secretion., Negative feedback regulation (−) is possible at three levels: target organ (ultrashort feedback), anterior pituitary (short feedback), and hypothalamus (long feedback).

Illustration A shows the endocrine feedback loop between the thyroid and the hypothalamus. T R H from hypothalamus releases T S H into the anterior pituitary. T sub 3 and T sub 4 are then released into the thyroid. The thyroid provides negative feedback to the anterior pituitary and the hypothalamus. Flowchart B shows the following mechanisms. • The hypothalamus is positively or negatively regulated by factors that stimulate or inhibit central nervous system control of hormone release. • The anterior pituitary is positively or negatively regulated by releasing hormones and factors and release-inhibiting hormones and factors. • The target organ is positively regulated by tropic hormones from the anterior pituitary. • The hormones from the target organ positively regulates the physiologic effect. The feedback loops through the mechanisms are as follows. • Tropic hormones provide an ultra-short negative feedback loop to the anterior pituitary. • Tropic hormones provide a short negative feedback loop to the hypothalamus. • Hormones from the target organ provide a negative feedback loop to the target organ. • Hormones from the target organ provide a short negative feedback loop to the anterior pituitary. • Hormones from the target organ provide a long positive or negative feedback loop to the hypothalamus. • Physiologic effect provides an ultra-short negative feedback loop to the target organ.

Hormone Transport

Once hormones are released into the circulatory system, they are distributed throughout the body. The protein (peptide) hormones (see Table 21.1) are water soluble and generally circulate in free (unbound) forms. Water-soluble hormones generally have a half-life of seconds to minutes because they are catabolized by circulating enzymes. For example, insulin has a half-life of 3 to 5 minutes and is catabolized by insulinases. Lipid-soluble hormones (see Table 21.1), such as cortisol and adrenal androgens, are transported bound to a water-soluble carrier or transport protein and can remain in the blood for hours to days. Only free hormones (those not bound to a carrier protein) can signal a target cell. At the cell membrane, lipid-soluble hormones dissociate from their carrier protein and diffuse into the cell. Because there is equilibrium between the concentrations of free hormones and hormones bound to plasma proteins, a significant change in the concentration of binding (carrier) proteins can affect the concentration of free hormones in the plasma. For example, malnutrition and liver disease can lower the serum levels of the carrier protein albumin, causing a decrease in the lipid-soluble hormones thyroxine, cortisol, and aldosterone. (Mechanisms of hormone binding are discussed in Chapter 1.) Free hormone levels can be measured using a variety of measurement techniques, including radioimmunoassay (RIA), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), or bioassay.

Hormone Receptors

Although a hormone is distributed throughout the body, only those cells with appropriate receptors for that hormone, termed target cells, are affected. Target cell response depends on blood levels of the hormone, the concentration of target cell receptors, and affinity of the receptor for the hormone. Hormone receptors of the target cell have two main functions: (1) to recognize and bind specifically and with high affinity (sensitivity) to their particular hormones, and (2) to initiate a signal to appropriate intracellular effectors.

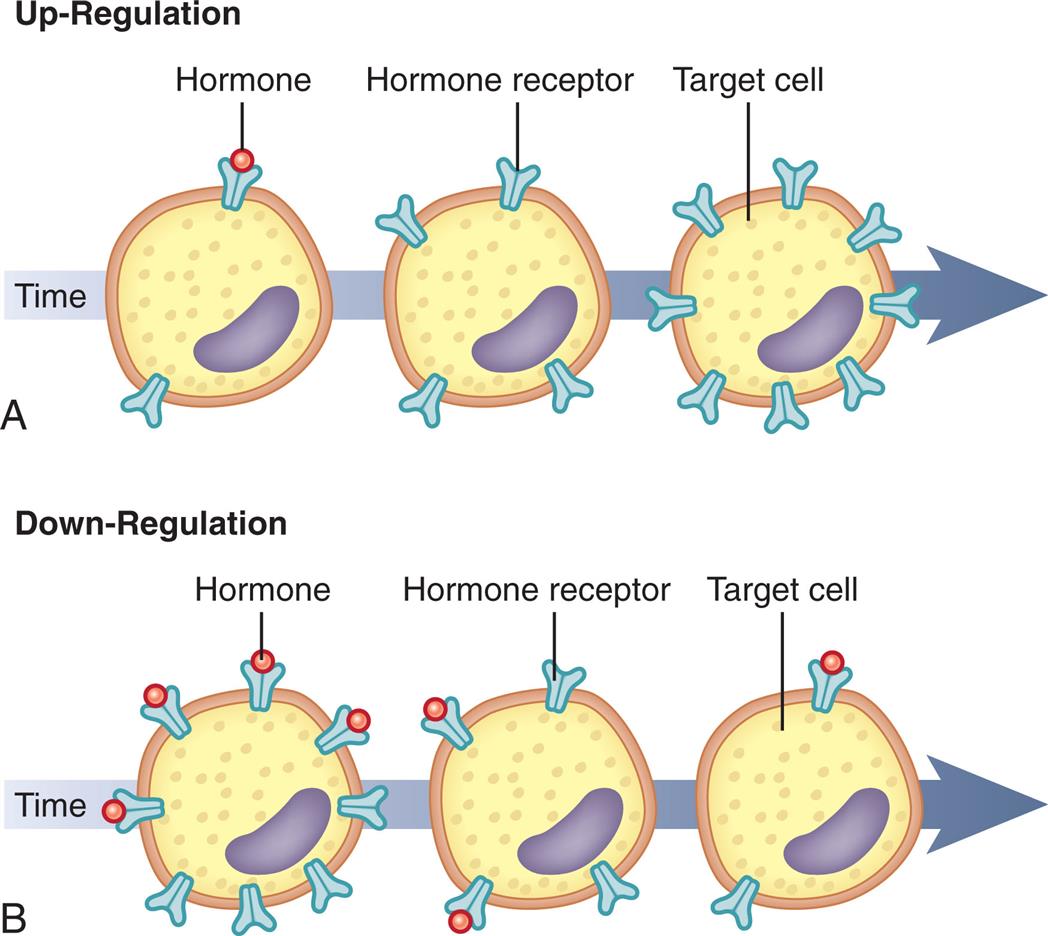

The sensitivity of the target cell to a particular hormone is related to the total number of receptors per cell or the affinity of the receptors for the hormone: the more receptors or the higher the affinity of the receptors, the more sensitive the cell to the stimulating effects of the hormone. Low concentrations of hormone increase the number or affinity of receptors per cell; this is called up-regulation (Fig. 21.3A). High concentrations of hormone decrease the number or affinity of receptors; this is called down-regulation (Fig. 21.3B). Thus, the cell can adjust its sensitivity to the concentration of the signaling hormone. The receptors on the plasma membrane are continuously synthesized and degraded, so that changes in receptor concentration or affinity may occur within hours. Various physiochemical conditions can affect both the receptor number and the affinity of the hormone for its receptor. Some of these physiochemical conditions are the fluidity and structure of the plasma membrane, pH, temperature, ion concentration, diet, and the presence of other chemicals (e.g., drugs). Finally, mutations may affect receptor number or structure. For example, mutations in TSH receptors can lead to resistance to thyroid hormone and can contribute to defective thyroid hormone production.1

(A) Low hormone level and up-regulation, or an increase in the number of receptors. (B) High hormone level and down-regulation, or a decrease in the number of receptors.

Illustration A is a timeline representing an up-regulation. There are three illustrations on the timeline, from the left to the right. • The target cell has two hormone receptors, with a hormone in one. • The target cell has four hormone receptors, with no hormones in any. • The target cell has eight hormone receptors, with no hormones in any. Illustration B is a timeline representing a down-regulation. There are three illustrations on the timeline, from the left to the right. • The target cell has eight hormone receptors, with hormones in four. • The target cell has four hormone receptors, with hormones in two. • The target cell has two hormone receptors, with a hormone in one.

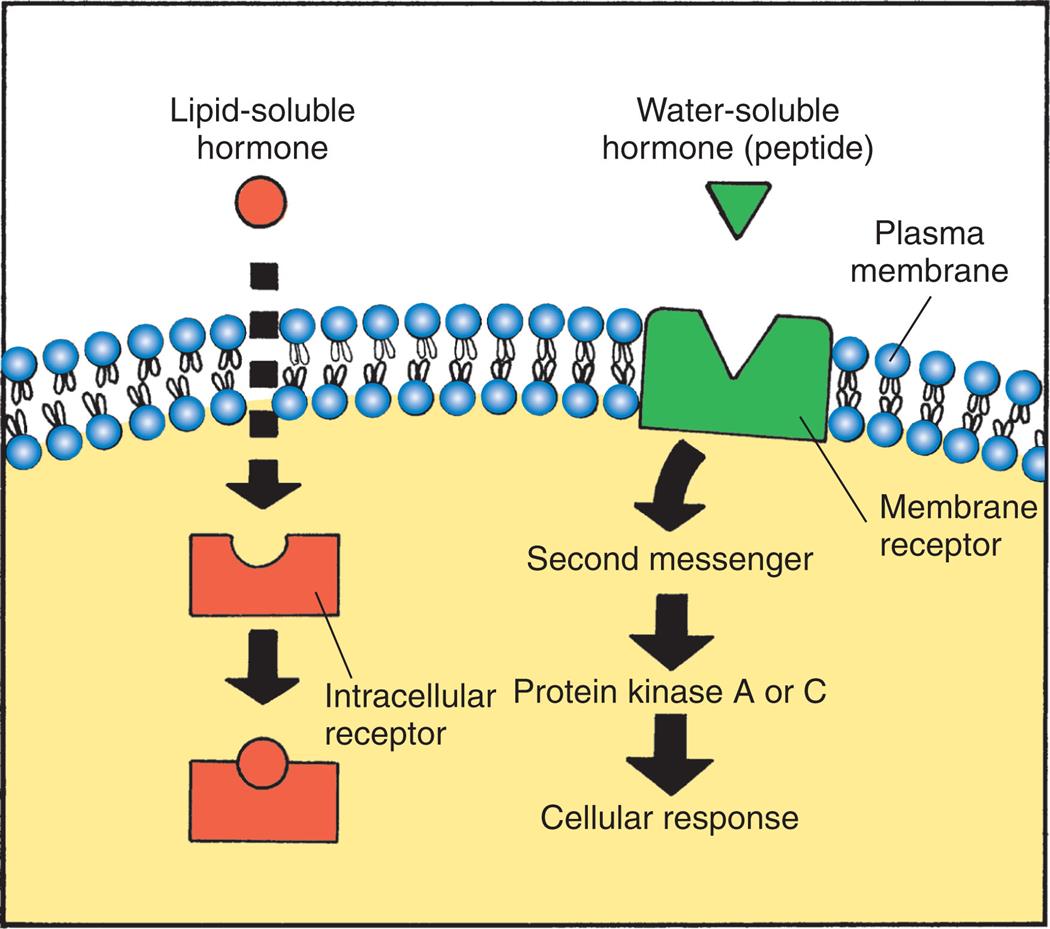

Hormone receptors may be located in the plasma membrane or in the intracellular compartment of the target cell (Fig. 21.4). Water-soluble hormones (peptide or nonsteroid hormones), which include the protein hormones and the catecholamines, have a high molecular weight and cannot diffuse across the cell membrane. They interact or bind with receptors located in or on the cell membrane and activate a second messenger to mediate short-acting responses. Lipid-soluble hormones (steroid hormones) diffuse freely across the plasma and nuclear membranes and bind with cytosolic or nuclear receptors, although receptors for some lipid-soluble hormones are located in or near the plasma membrane and facilitate rapid (non-genomic) effects.2

An illustration shows how hormones bind at the target cell. The illustration shows a target cell with a plasma membrane. A lipid-soluble hormone passes through the plasma membrane and attaches itself to the intracellular receptor. A membrane receptor embedded in the plasma membrane attracts a water-soluble hormone (peptide), activating the second messenger. The second messenger releases the protein kinase A or C, generating a cellular response.

Water-Soluble Hormone Receptors

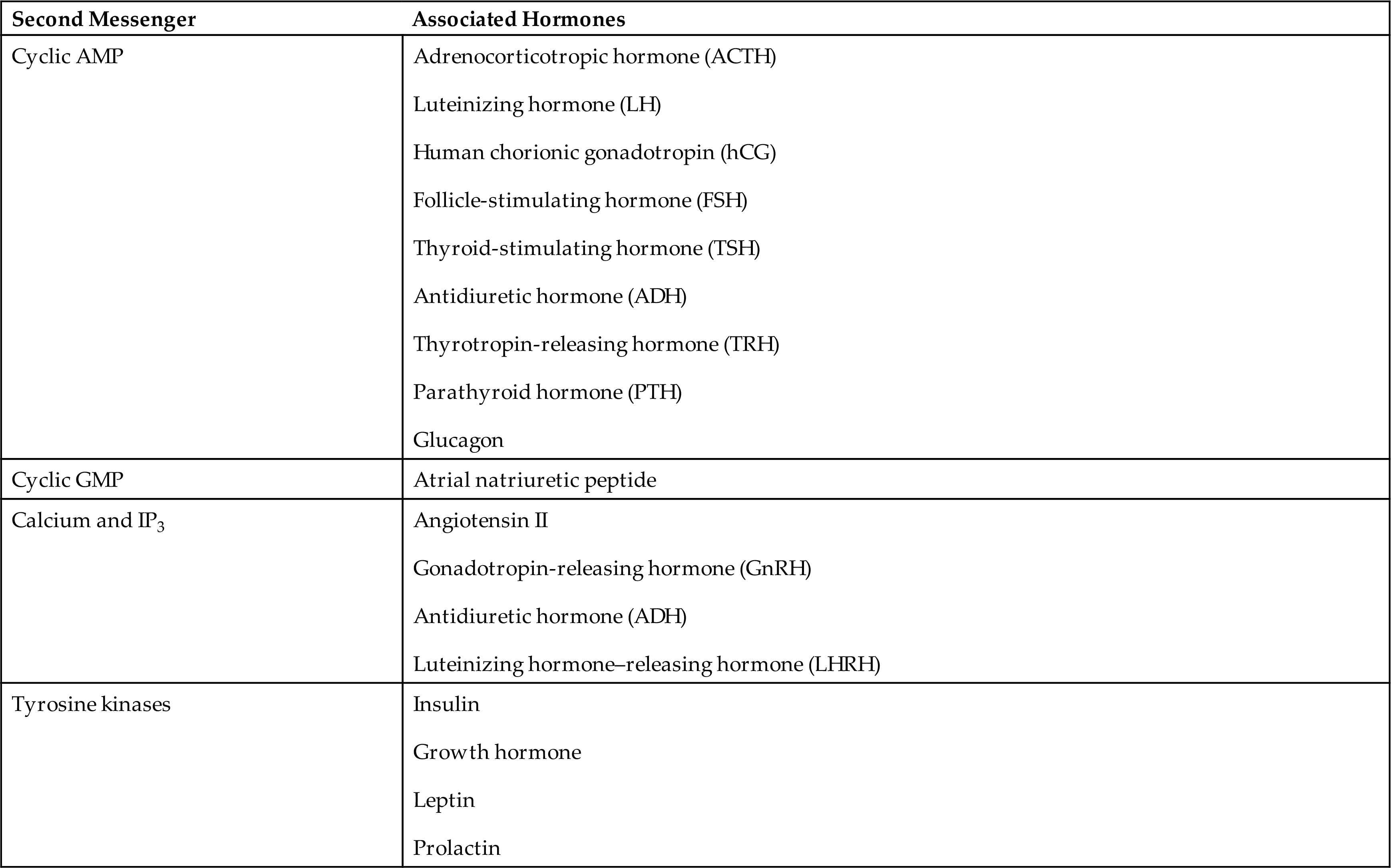

Water-soluble hormone binding with plasma membrane receptors initiates a complex cascade of intracellular effects. In this cascade, the hormone is termed the first messenger. The hormone-receptor interaction initiates a signal that generates a small molecule inside the cell, called the second messenger. The second messenger conveys the signal from the receptor to the cytoplasm and nucleus of the cell and mediates the effect of the hormone on the target cell. Second messengers include cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), calcium, inositol triphosphate (IP3), and the tyrosine kinase system (Table 21.2).

Table 21.2

| Second Messenger | Associated Hormones |

|---|---|

| Cyclic AMP | |

| Cyclic GMP | Atrial natriuretic peptide |

| Calcium and IP3 | |

| Tyrosine kinases |

AMP, Adenosine monophosphate; GMP, guanosine monophosphate; IP3, inositol triphosphate.

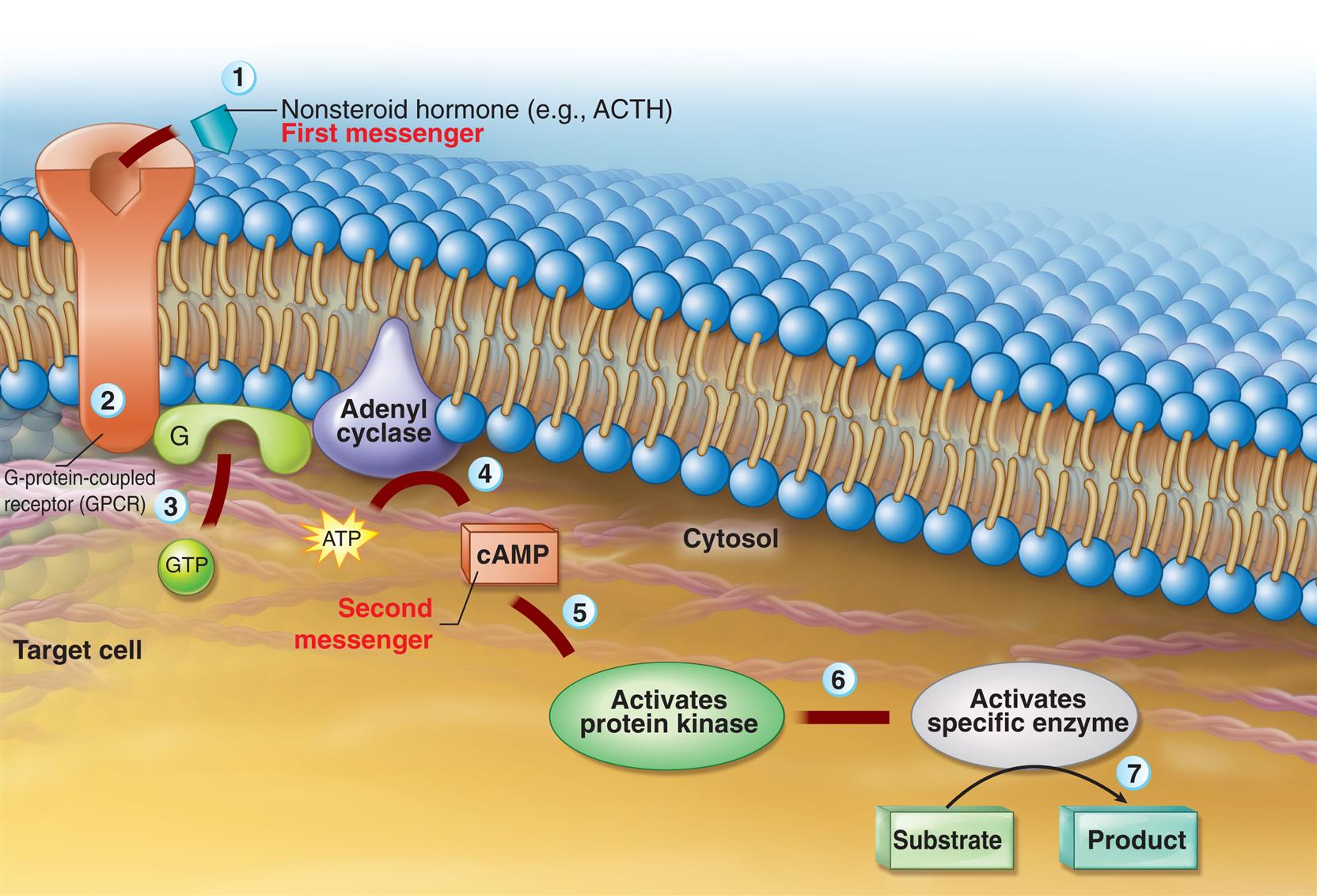

The second messenger cAMP increases when first messengers from the anterior pituitary gland, such as adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and TSH, bind to a cell membrane receptor. Increased levels of intracellular cAMP activate protein kinases, leading to activation or deactivation of intracellular enzymes (Fig. 21.5). cGMP also functions as a second messenger following receptor binding of first messengers (e.g., atrial natriuretic peptide and nitric oxide). These hormones and signaling molecules play crucial roles in cardiovascular and pulmonary health and disease. Drugs, such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors that sustain the action of cGMP are used in the treatment of erectile dysfunction and are being explored for the treatment of vascular and pulmonary hypertension and cognitive dysfunction.3,4

A water-soluble (nonsteroid) hormone acts as a first messenger and binds to a fixed receptor of the target cell (1). The hormone-receptor complex activates the G protein (2). The activated G protein (G) reacts with guanosine triphosphate (GTP), which in turn activates the membrane-bound enzyme adenylyl cyclase (3). Adenylyl cyclase catalyzes the conversion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP; second messenger) (4). cAMP activates protein kinase (5). Protein kinases activate specific intracellular enzymes (6). These activated enzymes then influence specific cellular reactions and metabolic pathways, thus producing the target cell's response to the hormone (7). ACTH, Adrenocorticotropic hormone. (From Patton KT, Thibodeau GA. Anatomy & physiology, 9th edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2016.)

The second messenger IP3 is increased in response to angiotensin II and antidiuretic hormone (ADH) receptor binding and triggers a release of intracellular calcium. This leads to the formation of the calcium-calmodulin complex, which mediates the effects of calcium on intracellular activities that are crucial for cell metabolism, growth, and smooth muscle contraction.

Some hormone first messengers, such as insulin, growth hormone (GH), and prolactin, bind to surface receptors that directly activate second messengers of the tyrosine kinase family. These tyrosine kinases include the Janus family of tyrosine kinases (JAK) and signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT). They regulate a wide range of intracellular processes that contribute to cellular metabolism, immunity, growth, apoptosis, and oncogenesis. They can be targeted for inhibition in treatments aimed at moderating immune-mediated responses, as in rheumatoid arthritis and cancer.5,6

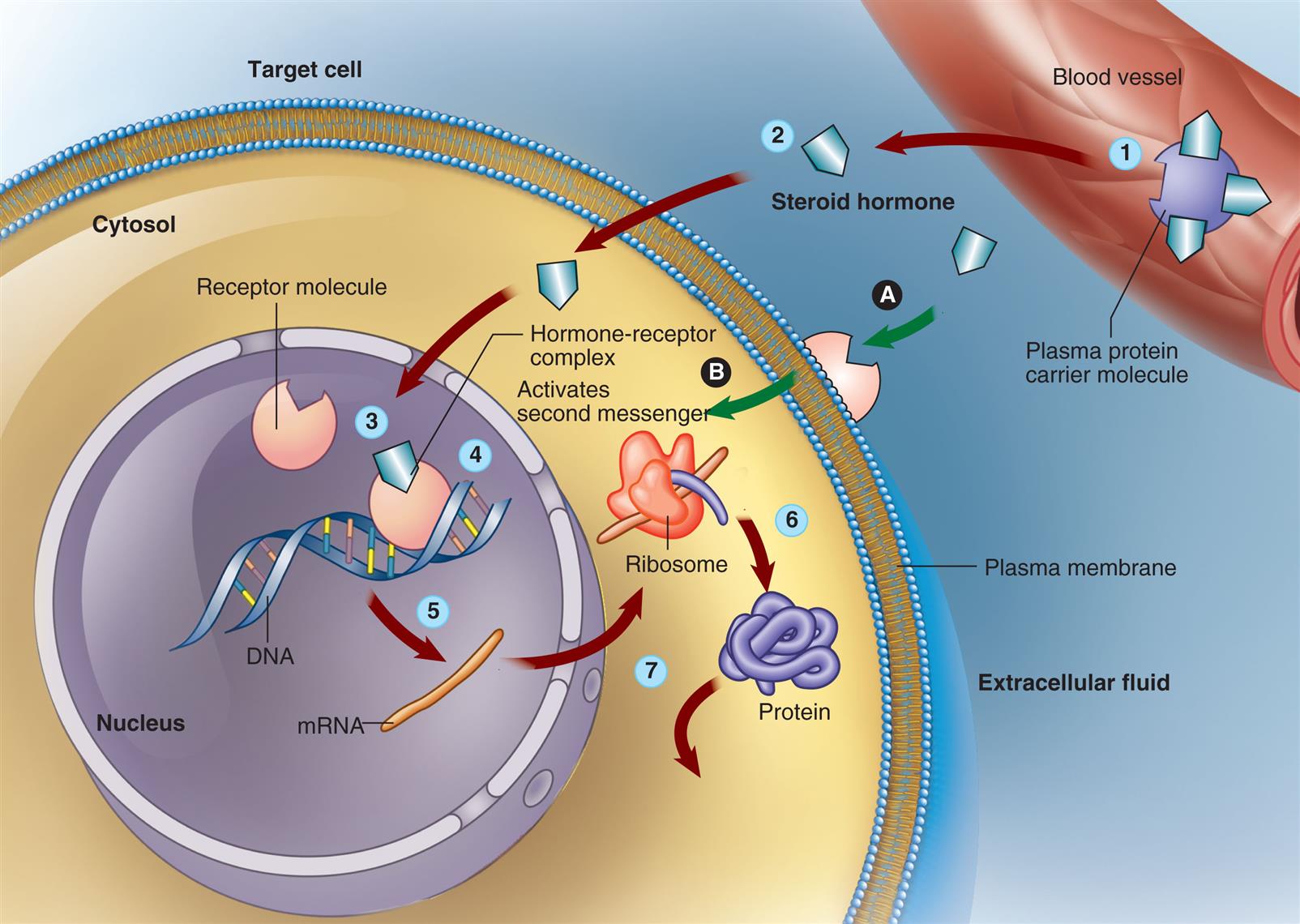

Lipid-Soluble Hormone Receptors

With the exception of thyroid hormones, the lipid-soluble hormones are synthesized from cholesterol (giving rise to the term “steroid”) (see Table 21.1). Receptors for lipid-soluble hormones are in the cytosol and nucleus, and directly modulate gene expression without complex second messengers (Fig. 21.6). Because these are relatively small, lipophilic, hydrophobic molecules, lipid-soluble hormones can cross the lipid plasma membrane by simple diffusion (see Chapter 1). They bind with cytosolic or nuclear receptors, which keeps them from diffusing back out of the cell. The effects of lipid-soluble hormones on cytosol and nuclear receptors can take hours to days. However, lipid hormone receptors for estrogen, thyroid hormone, and aldosterone are located in the plasma membrane and are associated with rapid responses (seconds or minutes) (see Fig. 21.6). These receptors, when activated, have primarily intracellular nongenomic (membrane-initiated steroid signaling) effects. Through crosstalk, nongenomic responses and gene transcription modulate each other, allowing cells to adapt rapidly to environmental changes.7,8

Lipid-soluble steroid hormone molecules detach from the carrier protein (1) and pass through the plasma membrane (2). Hormone molecules then diffuse into the nucleus, where they bind to a receptor to form a hormone-receptor complex (3). This complex then binds to a specific site on a deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecule (4), triggering transcription of the genetic information encoded there (5). The resulting messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) molecule moves to the cytosol, where it associates with a ribosome, initiating synthesis of a new protein (6). This new protein—usually an enzyme or channel protein—produces specific effects on the target cell (7). The classic genomic action is typically slow (red arrows). Steroids also may exact rapid effects (green arrows) by binding to receptors on the plasma membrane (A) and activating an intercellular second messenger (B). (From Patton KT, Thibodeau GA. Anatomy & physiology, 9th edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2016.)

Hormone Effects

The binding of hormones with their receptors stimulates three general types of effects by:

Hormones affect target cells directly or permissively. Direct effects are the obvious changes in cell function that specifically result from stimulation by a particular hormone. Permissive effects are less obvious hormone-induced changes that facilitate the maximal response or functioning of a cell and require the presence of another hormone. For example, thyroid hormone has a direct effect on lipid metabolism, causing increased concentration of serum fatty acids and a permissive effect on epinephrine by increasing the number of adrenergic receptors.

Structure and Function of the Endocrine Glands

Hypothalamic–Pituitary System

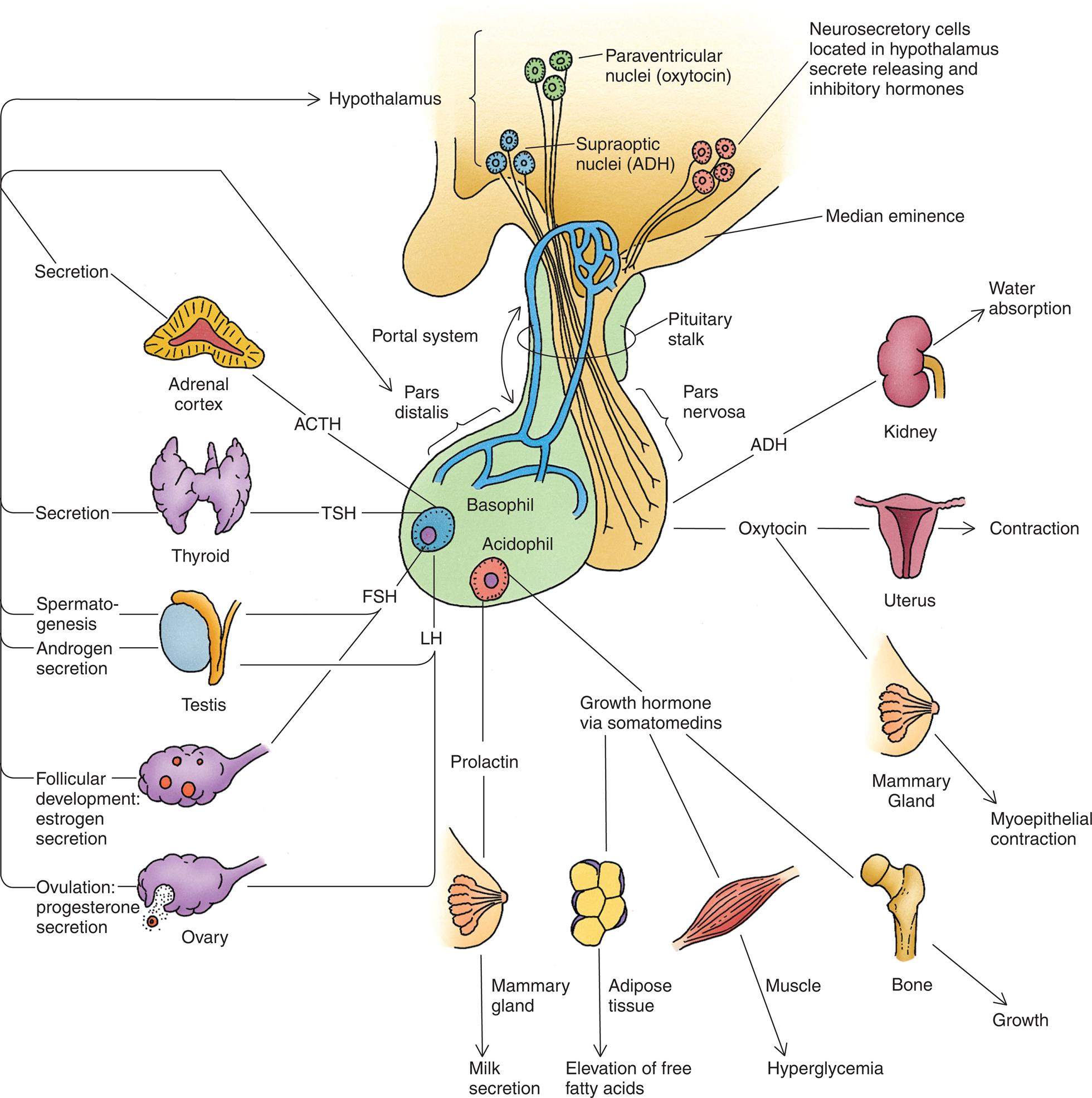

The hypothalamic–pituitary axis (HPA) forms the structural and functional basis for central integration of the neurologic and endocrine systems, creating what is called the neuroendocrine system. The HPA produces several hormones that affect a number of diverse body functions (Fig. 21.7), including thyroid, adrenal, and reproductive functions.

ACTH, Adrenocorticotropic hormone; ADH, antidiuretic hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone. (From Gartner LP, Hiatt JL. Color textbook of histology, 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.)

An illustration shows the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and its target organs. The followings structures and their target organs are identified, clockwise from the top. • Neurosecretory cells located in hypothalamus secrete releasing and inhibitory hormones. • Median eminence. • Pituitary stalk. • Pars nervosa. • A D G: kidney (water absorption). • Oxytocin: uterus (contraction) and mammary gland (myoepithelial contraction). • Acidophil: growth hormone via somatomedins (adipose tissue, elevation of free fatty acids; muscle, hyperglycemia; bone, growth) and prolactin (mammary gland, milk secretion). • Basophil. • Pars distalis. • Portal system. • Hypothalamus: paraventricular nuclei (oxytocin) and supraoptic nuclei (A D H). The hormones from basophil (acting on hypothalamus) and their corresponding target organs are as follows. • L H. Ovulation: progesterone secretion. • L H and F S H. Testis: spermatogenesis and androgen secretion. • F S H. Follicular development: estrogen secretion. • T S H. Thyroid: secretion. • A C T H. Adrenal cortex: secretion.

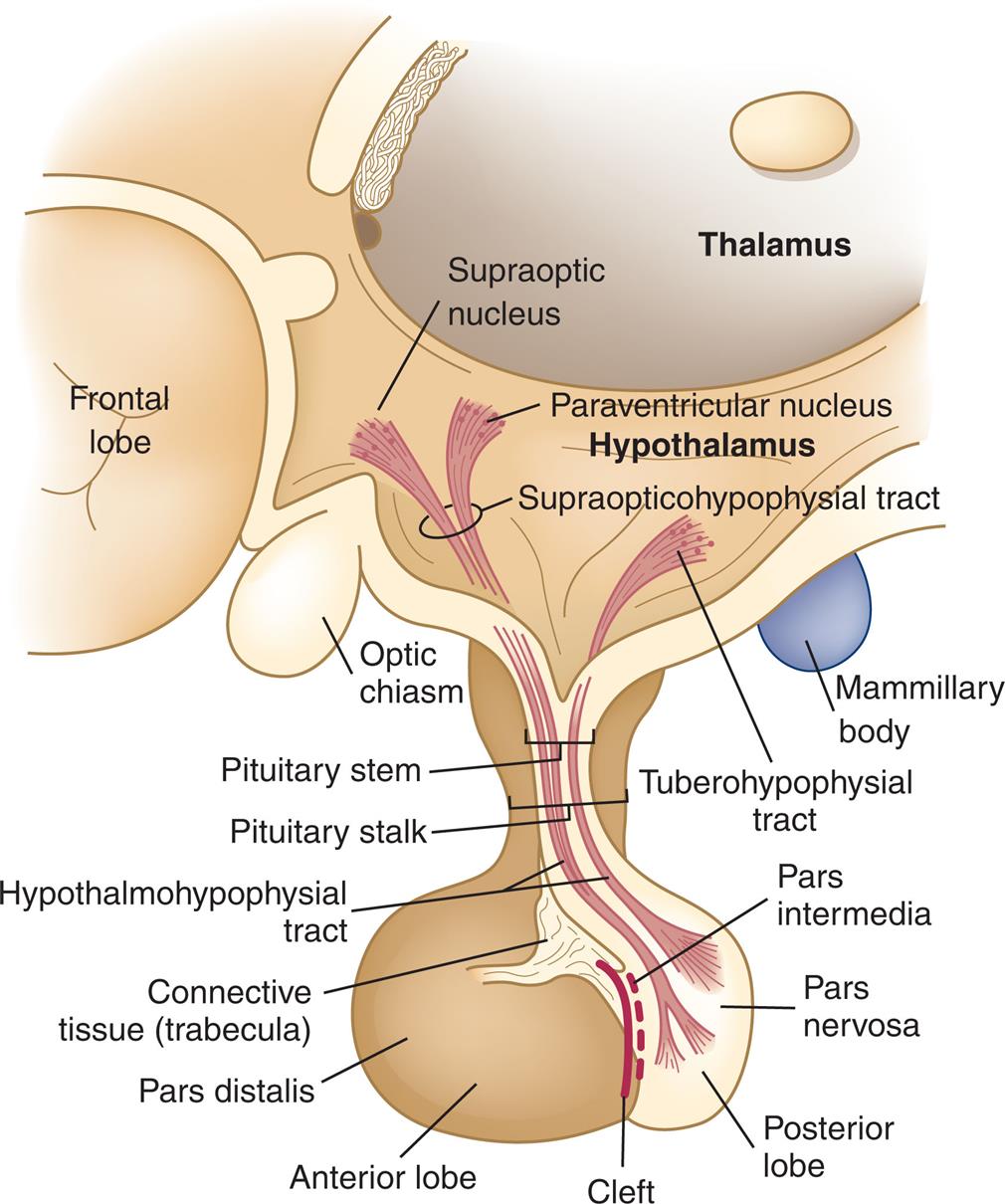

Hypothalamus

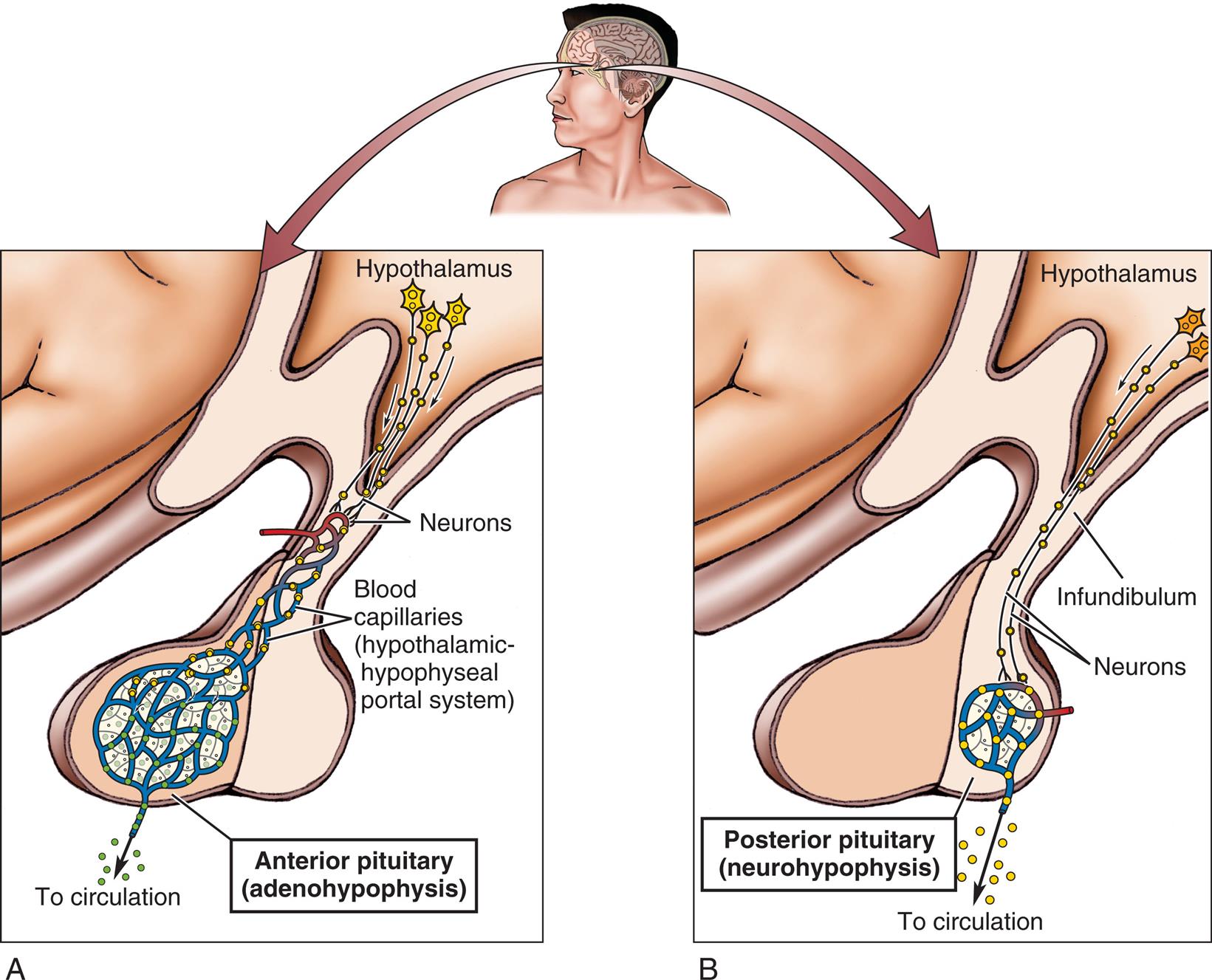

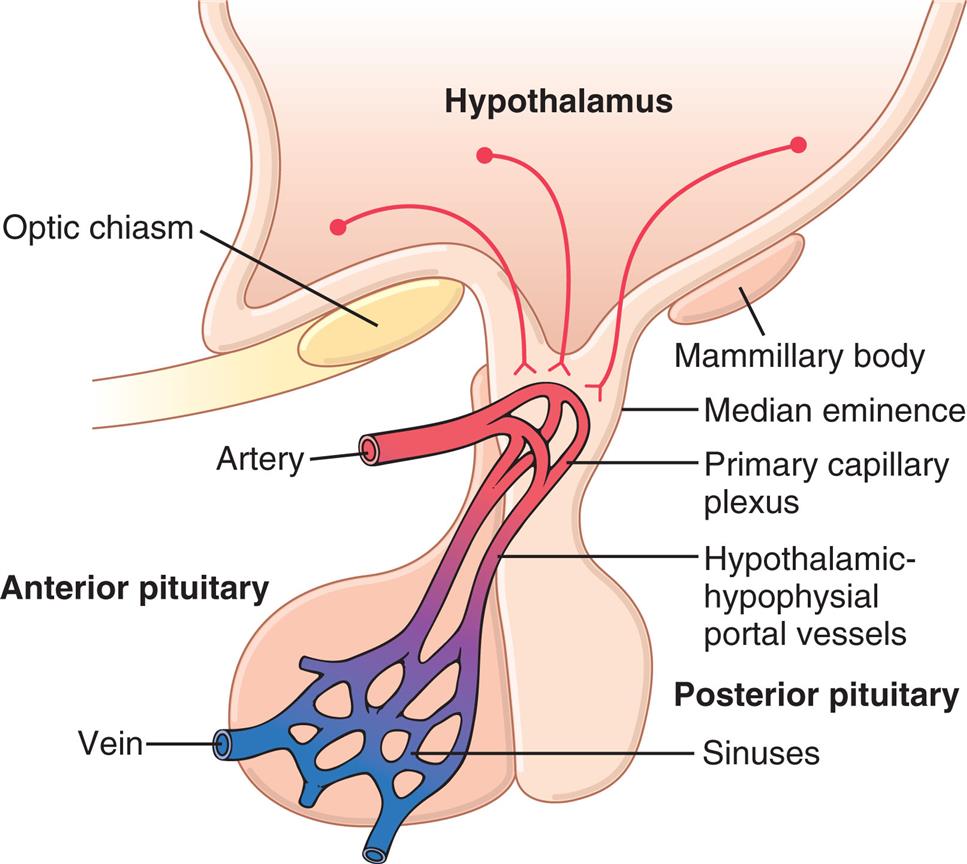

The hypothalamus is located at the base of the brain. It is connected to the pituitary gland by the infundibulum (pituitary stalk) (Fig. 21.8). The hypothalamus is connected to the anterior pituitary through hypophysial portal blood vessels (Fig. 21.9) and to the posterior pituitary via a nerve tract referred to as the hypothalamohypophysial tract (Fig. 21.10). These connections are vital to the functioning of the hypothalamic–pituitary system. The hypothalamus contains special neurosecretory cells that synthesize and secrete the hypothalamic-releasing hormones that regulate the release of hormones from the anterior pituitary. In addition, these cells synthesize the hormones ADH (also called vasopressin) and oxytocin, which are stored and released from the posterior pituitary gland. ADH and oxytocin travel to the posterior pituitary by way of the hypothalamohypophysial nerve tract. Releasing and inhibitory hormones are synthesized in the hypothalamus and are secreted into the portal blood vessels, through which they travel to their target tissues within the anterior pituitary and control the release of tropic hormones. These releasing/inhibitory hormones from the hypothalamus include prolactin-inhibiting hormone (PIH), prolactin-releasing hormone (PRH), TRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), hypothalamic somatostatin, growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH), corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), and substance P. These hormones are summarized in Table 21.3.

The pituitary gland sits within the sella turcica of the sphenoid bone of the skull. (A) Relationship of the hypothalamus to the anterior pituitary gland. (B) Relationship of the hypothalamus to the posterior pituitary gland. (From Herlihy B. The human body in health and illness, 5th edition. St. Louis: Saunders; 2015.)

Illustration A shows the anterior pituitary (adenohypophysis) and labels the following structures: hypothalamus, neurons, and blood capillaries (hypothalamic-hypophyseal portal system). The capillaries release neurons into circulation. Illustration B shows the posterior pituitary (neurohypophysis) and labels the following structures: hypothalamus, infundibulum, and neurons. The capillaries release neurons into circulation.

An illustration of the pituitary gland (anterior and posterior) shows and labels the following structures: hypothalamus, mammillary body, median eminence, primary capillary plexus, hypothalamic-hypophysial portal vessels, sinuses, vein, artery, and optic chiasm.

An illustration shows the frontal lobe, thalamus, hypothalamus, and the pituitary gland. The following structures in the illustration are labeled from the top to the bottom: supraoptic nucleus, paraventricular nucleus, supraopticohypophysial tract, optic chiasm, tuberohypophysial tract, mammillary body, pituitary stem, pituitary stalk, hypothalmohypophysial tract, connective tissue (trabecula), pars distalis, pars intermedia, pars nervosa, posterior lobe, cleft, anterior lobe.

Table 21.3

Pituitary Gland

The pituitary gland is located in the sella turcica (a saddle-shaped depression of the sphenoid bone at the base of the skull). It weighs approximately 0.5 g, except during pregnancy, when its weight increases by about 30%. It is composed of two distinctly different lobes: (1) the anterior pituitary, or adenohypophysis, and (2) the posterior pituitary, or neurohypophysis (see Fig. 21.8). These two lobes differ in their embryonic origins, cell types, and functional relationship to the hypothalamus.

Anterior Pituitary

The anterior pituitary (adenohypophysis) accounts for 75% of the total weight of the pituitary gland and is composed of three regions: (1) the pars distalis, (2) the pars tuberalis, and (3) the pars intermedia. The pars distalis is the major component of the anterior pituitary and is the source of the anterior pituitary hormones. The pars tuberalis is a thin layer of cells on the anterior and lateral portions of the pituitary stalk. The pars intermedia lies between the two and secretes melanocyte-stimulating hormone in the fetus. In the adult, the distinct pars intermedia disappears, and the individual cells are distributed diffusely throughout the pars distalis and pars nervosa (neural lobe) of the posterior pituitary.

The anterior pituitary is composed of two main cell types: (1) the chromophobes, which appear to be nonsecretory, and (2) the chromophils, which are the secretory cells of the adenohypophysis. The chromophils are subdivided into seven secretory cell types, and each cell type secretes a specific hormone or hormones. In general, the anterior pituitary hormones are regulated by (1) secretion of hypothalamic releasing factors, (2) feedback effects of the hormones secreted by target glands, and (3) direct effects of other mediating neurotransmitters.

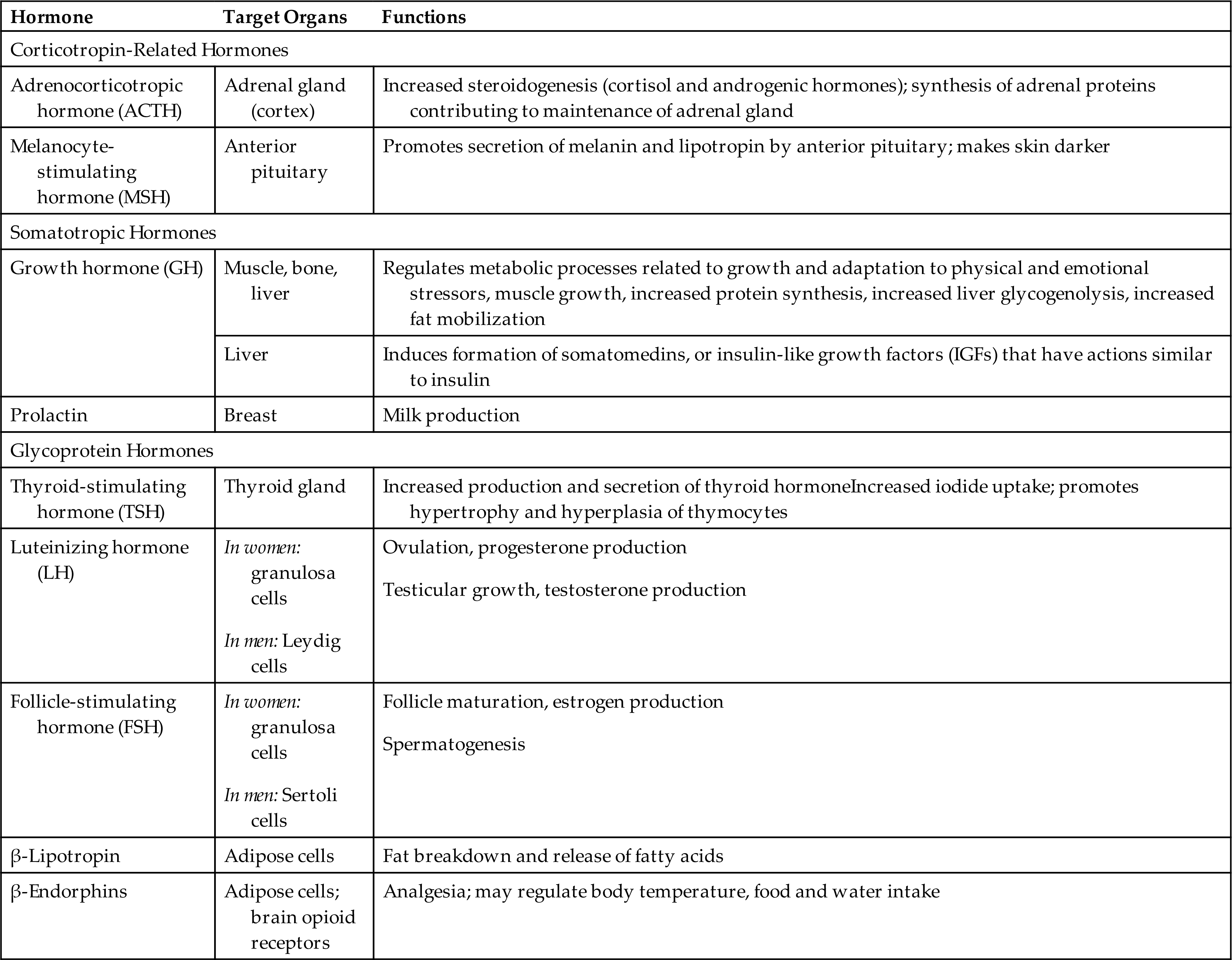

The anterior pituitary secretes tropic hormones that affect the physiologic function of specific target organs (see Fig. 21.7). These hormones can be grouped into three categories: corticotropin-related hormones, glycoproteins, and somatotropins (Table 21.4). Corticotropin-related hormones include melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH), which promotes the pituitary secretion of melanin to darken skin color, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which regulates the release of cortisol from the adrenal cortex. Also included in the corticotropic hormones are β-lipotropin, which plays a role in fat catabolism, and β-endorphins, which impact pain perception, body temperature, and food and water intake.

Table 21.4

The glycoprotein hormones follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) influence reproductive function and are discussed in Chapter 24. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), also a glycoprotein hormone, regulates the activity of the thyroid gland. The roles of ACTH and TSH are discussed later in this chapter.

The somatotropic hormones have diverse effects on body tissues and include GH and prolactin. Growth hormone secretion is controlled by two hormones from the hypothalamus: GHRH, which increases GH secretion; and somatostatin, which inhibits GH secretion. GH is essential to normal tissue growth and maturation and also impacts aging, sleep, nutritional status, stress, and reproductive hormones. In the bone, GH stimulates epiphyseal growth and increases osteoclast and osteoblast activity, resulting in increased bone mass. GH also increases amino acid transport in muscles. Other functions of GH include lipolysis and enhancement of hepatic protein synthesis.

Many of the anabolic functions of GH are mediated, at least in part, by the insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), also known as the somatomedins. There are two primary forms of IGF, IGF-1 and IGF-2, of which IGF-1 is the most biologically active. They both circulate bound to a group of IGF-binding proteins (IGFBPs) modulating their availability. IGF-1 binds to IGF-1 receptors, mediating the anabolic effects of GH. IGF-1 also binds to insulin receptors, providing an insulin-like effect on skeletal muscle. IGF-2 has important effects on fetal growth but suppresses GH in the adult. Because of the anabolic effects of GH and IGF-1, they can be used to treat growth disorders, increase muscle mass, and potentially slow the aging process; however, there are concerns about their safety, with potential links to increased rates of cancer.9

Prolactin primarily functions to induce milk production during pregnancy and lactation. It has immune stimulatory effects and modulates immune and inflammatory responses with both physiologic and pathologic reactions. Its synthesis and release are increased by stimulation of the nipples and mammary gland during nursing. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, serotonin, and growth factors also stimulate the synthesis of prolactin. Release of prolactin is inhibited by dopamine.

Posterior Pituitary

The embryonic posterior pituitary (neurohypophysis) is derived from the hypothalamus and is comprised of three parts: (1) the median eminence, located at the base of the hypothalamus; (2) the pituitary stalk; and (3) the infundibular process, also known as the pars nervosa or neural lobe. The median eminence is composed largely of the nerve endings of axons from the ventral hypothalamus. It often is designated as part of the posterior pituitary and contains at least 10 biologically active hypothalamic releasing hormones, as well as the neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, acetylcholine, and histamine. The pituitary stalk contains the axons of neurons that originate in the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus and connects the pituitary gland to the brain. Axons originating in the hypothalamus terminate in the pars nervosa, which secretes the hormones of the posterior pituitary (see Fig. 21.10).

The posterior pituitary secretes two polypeptide hormones: (1) ADH, also called arginine vasopressin; and (2) oxytocin. These hormones differ by only two amino acids. They are synthesized—along with their binding proteins, the neurophysins—in the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus (see Fig. 21.10). They are packaged in secretory vesicles and are moved down the axons of the pituitary stalk to the pars nervosa for storage. The posterior pituitary thus can be seen as a site for both storing and releasing hormones synthesized in the hypothalamus. The release of ADH and oxytocin is mediated by cholinergic and adrenergic neurotransmitters. The major stimulus to both ADH and oxytocin release is glutamate, whereas the major inhibitory input is through gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Before release into the circulatory system, ADH and oxytocin are split from the neurophysins and are secreted in unbound form.

Antidiuretic hormone

The major homeostatic function of the posterior pituitary is the control of plasma osmolality as regulated by antidiuretic hormone (ADH) (see Chapter 3). At physiologic levels, ADH increases the permeability of the distal renal tubules and collecting ducts (see Chapter 37). This increased permeability leads to increased water reabsorption into the blood, thus concentrating the urine and reducing serum osmolality. These effects may be inhibited by hypercalcemia, prostaglandin E, and hypokalemia.

The secretion of ADH is regulated primarily by the osmoreceptors of the hypothalamus, located near or in the supraoptic nuclei. As plasma osmolality increases, these osmoreceptors are stimulated, the rate of ADH secretion increases, thirst is stimulated (which increases water intake), and more water is reabsorbed by the kidney. This causes the plasma to become diluted back to its set-point osmolality. ADH has no direct effect on electrolyte levels, but by increasing water reabsorption, serum electrolyte concentrations may decrease because of a dilutional effect.2

ADH secretion also is stimulated by decreased intravascular volume, as monitored by baroreceptors in the left atrium, in the carotid arteries, and in the aortic arches. A volume loss of 7% to 25% acts through these receptors to stimulate ADH secretion. Stress, trauma, pain, exercise, nausea, nicotine, exposure to heat, and drugs, such as morphine, also increase ADH secretion. ADH secretion decreases with decreased plasma osmolality, increased intravascular volume, hypertension, alcohol ingestion, and an increase in estrogen, progesterone, or angiotensin II levels.

Physiologic levels of ADH do not significantly impact vessel tone. However, ADH was originally named vasopressin because, at extremely high levels, it causes vasoconstriction and a resulting increase in arterial blood pressure. For example, high doses of ADH (given as the drug vasopressin) may be administered to achieve hemostasis during hemorrhage and to raise blood pressure in shock states.

Oxytocin

Oxytocin is responsible for contraction of the uterus and milk ejection in lactating women and may affect sperm motility in men. In both genders, oxytocin has an antidiuretic effect similar to that of ADH. In women, oxytocin is secreted in response to suckling and mechanical distention of the female reproductive tract. Oxytocin binds to its receptors on myoepithelial cells in the mammary tissues and causes contraction of those cells, which increases intramammary pressure and milk expression (“let-down” reflex). Oxytocin acts on the uterus near the end of labor to enhance the effectiveness of contractions, promote delivery of the placenta, and stimulate postpartum uterine contractions, thereby preventing excessive bleeding. The function of this hormone is discussed in detail in Chapter 24.

Pineal Gland

The pineal gland is located near the center of the brain (see Fig. 21.1) and is composed of photoreceptive cells that secrete melatonin. It is innervated by noradrenergic sympathetic nerve terminals controlled by pathways within the hypothalamus. Melatonin release is stimulated by exposure to dark and inhibited by light exposure. It is synthesized from tryptophan, which is first converted to serotonin and then to melatonin. Melatonin regulates circadian rhythms and reproductive systems, including the secretion of the GnRHs and the onset of puberty. It also plays an important role in immune regulation and is postulated to impact the aging process. Further effects of melatonin include increasing nitric oxide release from blood vessels, removing toxic oxygen free radicals, and decreasing insulin secretion. Melatonin has been used therapeutically in humans to help with sleep disturbances, jet lag, and psychological and inflammatory disorders. Its utility for numerous other disorders is being explored.

Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands

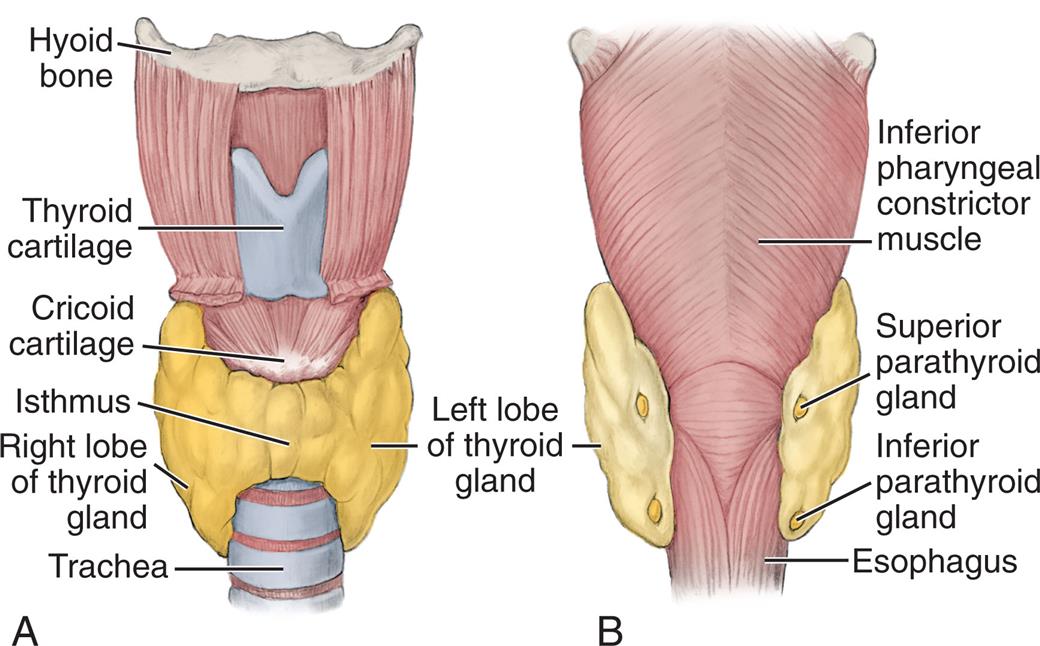

The thyroid gland, located in the neck just below the larynx, produces hormones that control the rates of metabolic processes throughout the body. The four parathyroid glands are near the posterior side of the thyroid and function to control serum calcium levels (Fig. 21.11).

(A) Anterior view. (B) Posterior view. (From Fehrenbach MJ, Herring SW. Illustrated anatomy of the head and neck, 4th edition. St. Louis: Saunders; 2012.)

Illustration A is the anterior view of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. The following structures are labeled from the top to the bottom: hyoid bone, thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, isthmus, right lobe of thyroid gland, left lobe of thyroid gland, and trachea. Illustration B is the posterior view of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. The following structures are labeled from the top to the bottom: inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle, superior parathyroid gland, inferior parathyroid gland, and esophagus.

Thyroid Gland

Two lobes of the thyroid gland lie on either side of the trachea, inferior to the thyroid cartilage and joined by a small band of tissue termed the isthmus (see Fig. 21.11). The pyramidal lobe is superior to the isthmus. The normal thyroid gland is not visible on inspection, but it may be palpated on swallowing, which causes it to be displaced upward.

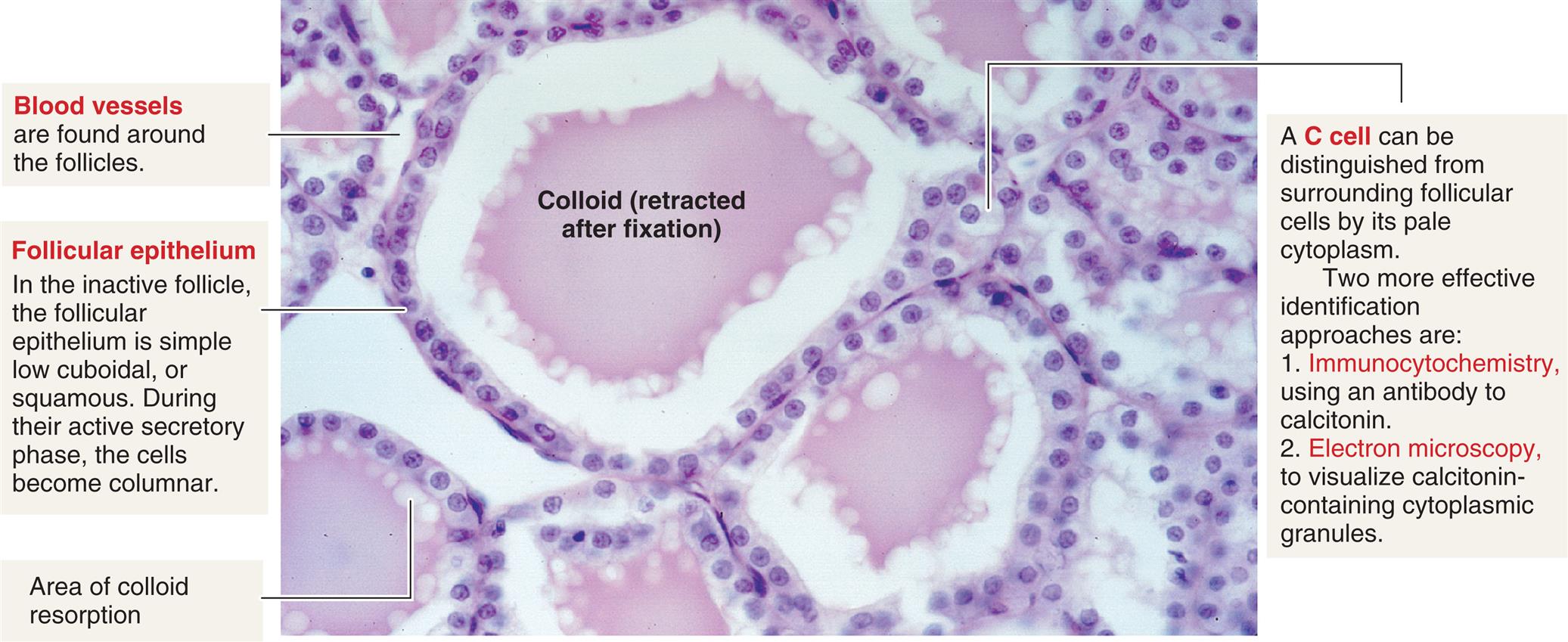

The thyroid gland consists of follicles that contain follicular cells surrounding a viscous substance called colloid (Fig. 21.12). The follicular cells synthesize and secrete the thyroid hormones. Neurons terminate on blood vessels within the thyroid gland and on the follicular cells themselves, so neurotransmitters (acetylcholine, catecholamines) may directly affect the secretory activity of follicular cells and thyroid blood flow. Approximately a 2-month supply of thyroid hormone is stored in the gland.

A photomicrograph of thyroid follicle cells. The colloid (retracted after fixation) is labeled. Other structures labeled and described are as follows. • Blood vessels are found around the follicles. • Follicular epithelium. In the inactive follicle, the follicular epithelium is simple low cuboidal, or squamous. During their active secretory phase, the cells become columnar. • Area of colloid resorption. • A C cell can be distinguished from surrounding follicular cells by its pale cytoplasm. Two more effective identification approaches are: 1. Immunocytochemistry, using an antibody to calcitonin. 2. Electron microscopy, to visualize calcitonin-containing cytoplasmic granules.

Also found in the thyroid are parafollicular cells, or C cells (see Fig. 21.12). C cells secrete various regulatory peptides, including calcitonin and, in much smaller quantities, the neuropeptides ghrelin, serotonin, and somatostatin. At high levels, calcitonin, also called thyrocalcitonin, lowers serum calcium levels by inhibiting bone-resorbing osteoclasts. However, in humans the metabolic consequences of calcitonin deficiency or excess do not appear to be significant. (Bone resorption is explained in Chapter 43). Calcitonin can be used therapeutically to treat a number of bone disorders, including osteogenesis imperfecta, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, hypercalcemia, Paget bone disease, and metastatic cancer of the bone. The precursor molecule to calcitonin, called procalcitonin, is a stress hormone that is elevated in infectious and inflammatory disorders, and its measurement can aid in the diagnosis of these serious diseases.10,11

Regulation of thyroid hormone secretion

Thyroid hormone (TH) is regulated through a negative-feedback loop involving the hypothalamus, the anterior pituitary, and the thyroid gland (see Fig. 21.2A). This loop is initiated by thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), which is synthesized and stored within the hypothalamus. TRH is released into the hypothalamic-pituitary portal system and circulates to the anterior pituitary, where it stimulates the release of TSH. TRH levels increase with exposure to cold or stress and from decreased levels of T4.

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is a glycoprotein synthesized and stored within the anterior pituitary. When TSH is secreted by the anterior pituitary, it circulates to bind with TSH receptors on the plasma membrane of the thyroid follicular cells. The primary effects of TSH on the thyroid gland include (1) an immediate increase in the release of stored thyroid hormones, (2) an increase in iodide uptake and oxidation, (3) an increase in thyroid hormone synthesis, and (4) an increase in the synthesis and secretion of prostaglandins by the thyroid. TSH also increases growth of the thyroid gland by stimulating thymocyte hyperplasia and hypertrophy and decreasing apoptosis. As TH levels rise, there is a negative-feedback effect on the HPA to inhibit TRH and TSH release, which then results in decreased TH synthesis and secretion. TH synthesis is also controlled by serum iodide levels and by circulating selenium-dependent enzymes, called deiodinases, which inactivate the precursor molecule thyroxine. Thyroid gland hormones and their regulation and function are summarized in Table 21.5.

Table 21.5

CNS, Central nervous system; GHIH, growth hormone–inhibiting hormone; GI, gastrointestinal; PTH, parathyroid hormone; RBC, red blood cell; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

From Monahan FD, Sands JK, Neighbors M, et al. Phipps’ medical-surgical nursing: Health and illness perspectives, 8th edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2007.

Synthesis of thyroid hormone

Thyroid hormone synthesis is summarized in these steps:

- 1. Uniodinated thyroglobulin (a large glycoprotein) is produced by the endoplasmic reticulum of the thyroid follicular cells.

- 2. Tyrosine (an amino acid) is incorporated into the thyroglobulin of follicular cells as it is synthesized.

- 3. Iodide (the inorganic form of iodine) is actively transferred from the blood into the colloid by carrier proteins located in the outer membrane of the follicular cells. This active transport system is called the iodide trap and is very efficient at accumulating the trace amounts of iodide from the blood.

- 4. Iodide is oxidized and quickly attaches to tyrosine within the thyroglobulin molecule.

- 5. Coupling of iodinated tyrosine forms thyroid hormones. Triiodothyronine (T3) is formed from the coupling of monoiodotyrosine (one iodine atom and tyrosine) and diiodotyrosine (two iodine atoms and tyrosine). Tetraiodothyronine (T4), commonly known as thyroxine, is formed from the coupling of two diiodotyrosines.

- 6. Thyroid hormones are stored attached to thyroglobulin within the colloid until they are released into the circulation.

The thyroid gland normally produces 90% T4 and 10% T3. Once released into the circulation, T3 and T4 are primarily transported bound to thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG), though some TH is transported by thyroxine-binding prealbumin (transthyretin), albumin, or lipoproteins. The bound form serves as a reservoir, whereas the unbound (free) form is active. In the body tissues, most of the T4 is converted to T3, which acts on the target cell.

Actions of thyroid hormone

TH has a significant effect on the growth, maturation, and function of cells and tissues throughout the body. TH binds to intracellular receptor complexes and then influences the genetic expression of specific proteins. TH is essential for normal growth and neurologic development in the fetus and infant and affects metabolic, neurologic, cardiovascular, and respiratory functioning across the life span. In addition, TH is required for the metabolism and function of blood cells, normal muscle functioning, the integrity of skin, nails, and hair, and for normal skeletal growth and maintenance of bone mass. Similar to some steroid hormones, TH also affects cell metabolism by altering protein, fat, and glucose metabolism and, as a result, increasing heat production and oxygen consumption.

TH has permissive effects throughout the body, optimizing the actions of other hormones and neurotransmitters. These effects can become very pronounced when there are either high or low levels of circulating thyroid hormones. For example, in the heart, T3 stimulates the synthesis of specific contractile proteins, sarcolemmal ion pumps, and membrane receptors. Therefore, in hyperthyroidism, which is associated with elevated levels of thyroid hormones, cardiac effects include increased heart rate and cardiac output, as well as the development of cardiomyopathy. Thyroid hormones also affect the respiratory center, contributing to the normal hypoxic and hypercapnic drives. In severe hypothyroidism, ventilation can become very depressed. Thyroid hormone also plays a role in metabolic disorders and liver disease (see Emerging Science Box: Thyromimetics and Liver Disease). Hypothyroidism is also associated with impaired bone formation, and hyperthyroidism is associated with osteoporosis, hypercalcemia, and hypercalciuria.

Parathyroid Glands

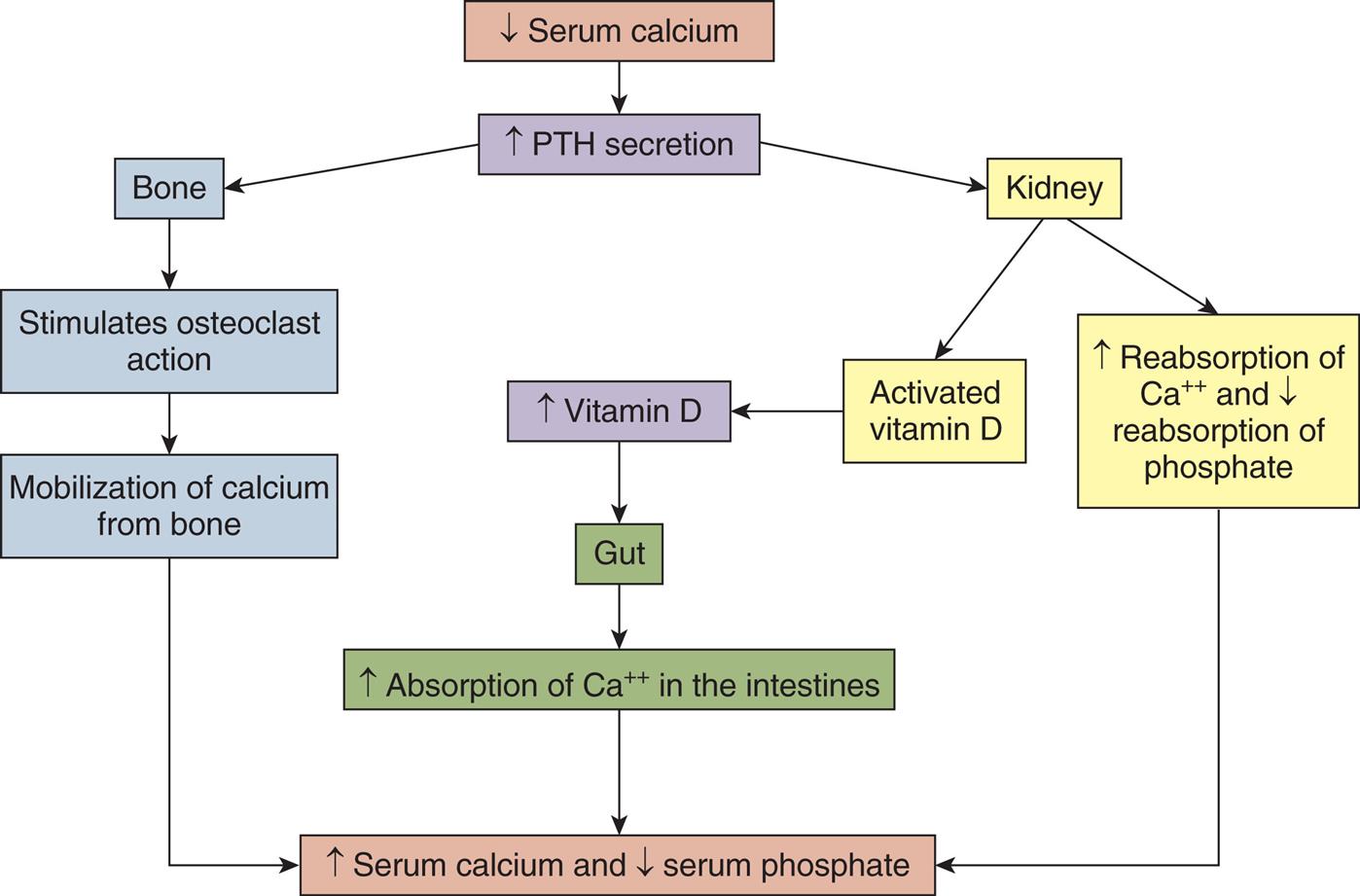

Normally, two pairs of small parathyroid glands are present behind the upper and lower poles of the thyroid gland (see Fig. 21.11). However, their number may range from two to six. The parathyroid glands produce parathyroid hormone (PTH), which is the single most important factor in the regulation of the serum calcium concentration. The overall effect of PTH secretion is to increase serum calcium concentration and decrease the concentration of serum phosphate. A decrease in serum-ionized calcium level stimulates PTH secretion. On release, PTH enters the circulation in unbound form and attaches to plasma membrane receptors in target tissues. To achieve regulation of serum calcium concentration, PTH acts directly on bone with at least two effects. In acute hypocalcemia, PTH secretion stimulates osteoblasts to release factors that cause osteoclast proliferation, maturation, and release of acidic enzymes, such as cathepsin. These enzymes mobilize calcium release from bone (bone resorption), which increases the serum calcium level (Fig. 21.13). There is bone remodeling with chronic stimulation by PTH, a process in which bone is broken down and re-formed. Paradoxically, when PTH is administered intermittently and at a low dose, it stimulates bone formation. This observation led to the use of synthetic PTH for treatment of osteoporosis.12

A flowchart shows the role of parathyroid hormone and vitamin D in calcium metabolism. • Decreased serum calcium leads to increased P T H secretion. • Increased P T H secretion affects bone and kidney. • Bone stimulates osteoclast action leading to mobilization of calcium from bone. • Kidney activates vitamin D leading to increased vitamin D, affecting the gut, which leads to increased absorption of calcium ions in the intestines. • Kidney increases reabsorption of calcium ions and decreases reabsorption of phosphate. Mobilization of calcium from bone, increased absorption of calcium ions in the intestines, and increased reabsorption of calcium ions and decreased reabsorption of phosphate leads to increased serum calcium and decreased serum phosphate.

PTH also acts on the kidney to increase calcium reabsorption in the distal tubules of the nephron while phosphate and bicarbonate reabsorption are decreased in the proximal tubules. The resultant increase in the serum calcium concentration inhibits PTH secretion. 1,25-Dihydroxy-vitamin D3 (the active form of vitamin D) is activated by the kidney and works as a cofactor with PTH to promote calcium and phosphate absorption in the gut and enhance bone mineralization. Vitamin D also plays an important role in metabolic processes and controlling inflammation. It has been found to be deficient in the majority of individuals in the United States (see Emerging Science Box: Vitamin D Deficiency).

Phosphate and magnesium concentrations also affect PTH secretion. An increase in the serum phosphate level decreases the serum calcium level by causing calcium-phosphate precipitation into soft tissue and bone, which indirectly stimulates PTH secretion. Hypomagnesemia in persons with normal calcium levels acts as a mild stimulant to PTH secretion; however, in persons with hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia decreases PTH secretion.

Another hormone that plays an important role in calcium and bone physiology is parathyroid hormone–related protein (PTHrP). This hormone is synthesized in many adult and fetal tissues and affects tissues around it in a paracrine fashion with multiple metabolic effects. It has similar biologic properties to PTH and uses the same receptors but has other actions mediated by different regions within the molecule. It is important for endochondral bone formation and bone remodeling.13

Endocrine Pancreas

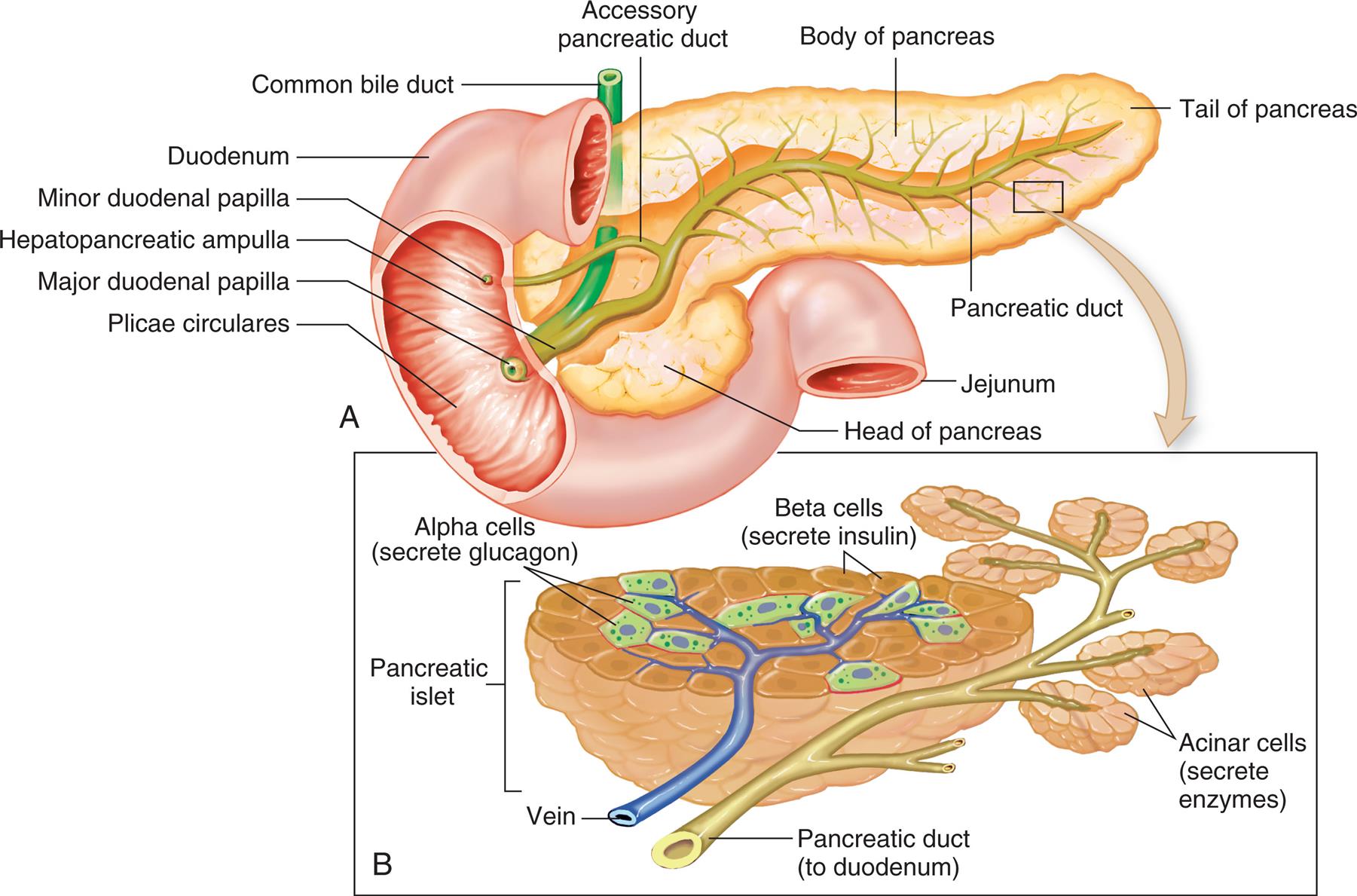

The pancreas is both an endocrine gland that produces hormones and an exocrine gland that produces digestive enzymes. (The exocrine function of the pancreas is discussed in Chapter 40.) The pancreas is located behind the stomach, between the spleen and the duodenum (Fig. 21.14). The pancreas houses pancreatic islets (islets of Langerhans), which are small islands of hormone-producing cells. The islets of Langerhans have four types of hormone-secreting cells: alpha cells, which secrete glucagon; beta cells, which secrete insulin and amylin; delta cells, which secrete gastrin and somatostatin; and F (or PP) cells, which secrete pancreatic polypeptide. These hormones regulate carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism. (The pancreas is illustrated in Fig. 21.14.) Nerves from both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system innervate the pancreatic islets.

(A) Pancreas dissected to show main and accessory ducts. The main duct may join the common bile duct, as shown here, to enter the duodenum by a single opening at the major duodenal papilla, or the two ducts may have separate openings. The accessory pancreatic duct is usually present and has a separate opening into the duodenum. (B) Exocrine glandular cells (around small pancreatic ducts) and endocrine glandular cells of the pancreatic islets (adjacent to blood capillaries). Exocrine pancreatic cells secrete pancreatic juice, alpha endocrine cells secrete glucagon, and beta cells secrete insulin. (From Patton KT, Thibodeau GA. Structure & function of the body, 15th edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2016.)

Illustration A is a cross-section of the pancreas. The following structures on the illustration are labeled clockwise from the left: plicae circulares, major duodenal papilla, hepatopancreatic ampulla, minor duodenal papilla, duodenum, common bile duct, accessory pancreatic duct, body of pancreas, tail of pancreas, pancreatic duct, jejunum, and head of pancreas. Illustration B is a cross-section of the head of pancreas. The following structures are labeled: • Alpha cells (secrete glucagon). • Beta cells (secrete insulin). • Acinar cells (secrete enzymes). • Pancreatic duct (to duodenum). • Vein. • Pancreatic islet.

The perfusion of the anterior lobe of the pancreas, where alpha, beta, and delta cells are most numerous, comes from branches of the superior mesenteric artery. The posterior lobe is perfused by branches of the celiac artery. The pancreatic islets receive 10% of the pancreatic blood flow but represent only 1% of pancreatic mass. This is necessary for oxygenation and delivery of islet hormones to target cells.

Insulin

The beta cells of the pancreas synthesize insulin from the precursor proinsulin, which is formed from a larger precursor molecule, preproinsulin. Proinsulin is composed of A peptide and B peptide, which are connected by a C peptide and two disulfide bonds. C peptide is cleaved by proteolytic enzymes, leaving the bonded A and B peptides as the insulin molecule. Insulin circulates freely in the plasma and is not bound to a carrier. C peptide level can be measured in the blood and used as an indirect measurement of serum insulin synthesis.

Secretion of insulin is regulated by chemical, hormonal, and neural control. The primary stimulus for insulin secretion is an increase in blood levels of glucose. Insulin secretion also is stimulated by the parasympathetic nervous system, usually before eating a meal. Other factors stimulating insulin secretion include some amino acids (leucine, arginine, and lysine) and gastrointestinal hormones (glucagon, gastrin, cholecystokinin, secretin). Insulin secretion diminishes in response to low blood levels of glucose (hypoglycemia), high levels of insulin (through negative feedback to the beta cells), and sympathetic stimulation of the beta cells in the islets. Prostaglandins also inhibit insulin secretion.

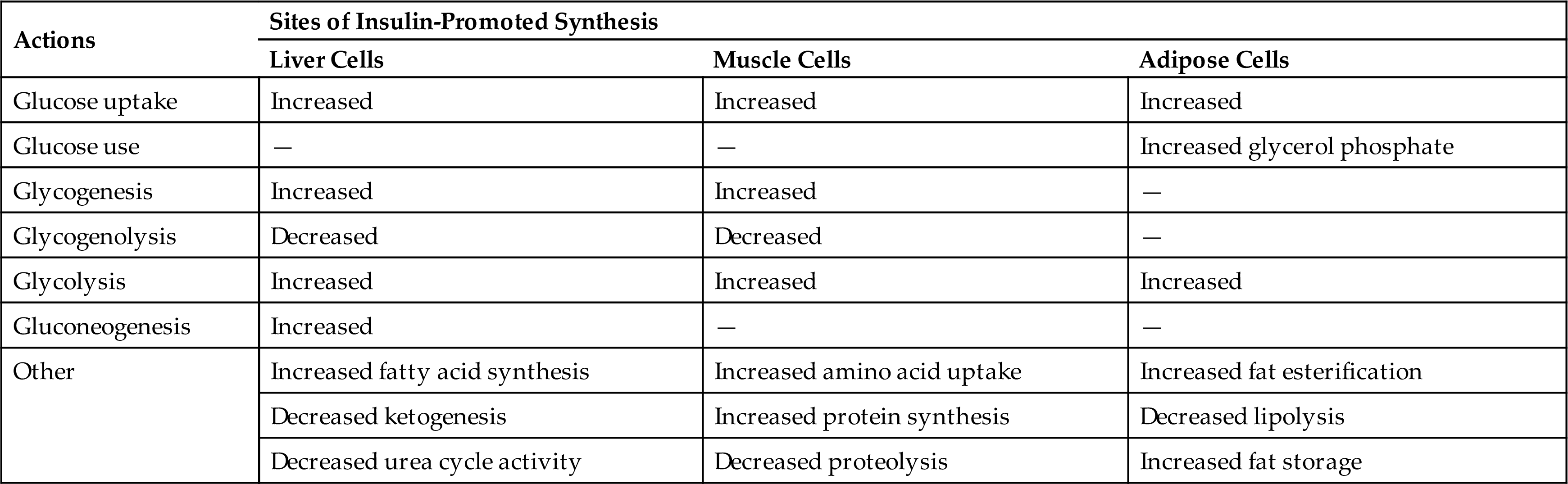

Insulin is an anabolic hormone that promotes glucose uptake, primarily in liver, muscle, and adipose tissue. It also increases the synthesis of proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids. The net effect of insulin in these tissues is to stimulate protein and fat synthesis and decrease blood glucose level. Insulin also facilitates the intracellular transport of potassium (K+), phosphate, and magnesium. Table 21.6 summarizes the actions of insulin. Insulin is metabolized in the liver and kidney by enzymes that split disulfide bonds. Very little insulin is excreted unchanged in the urine.

Table 21.6

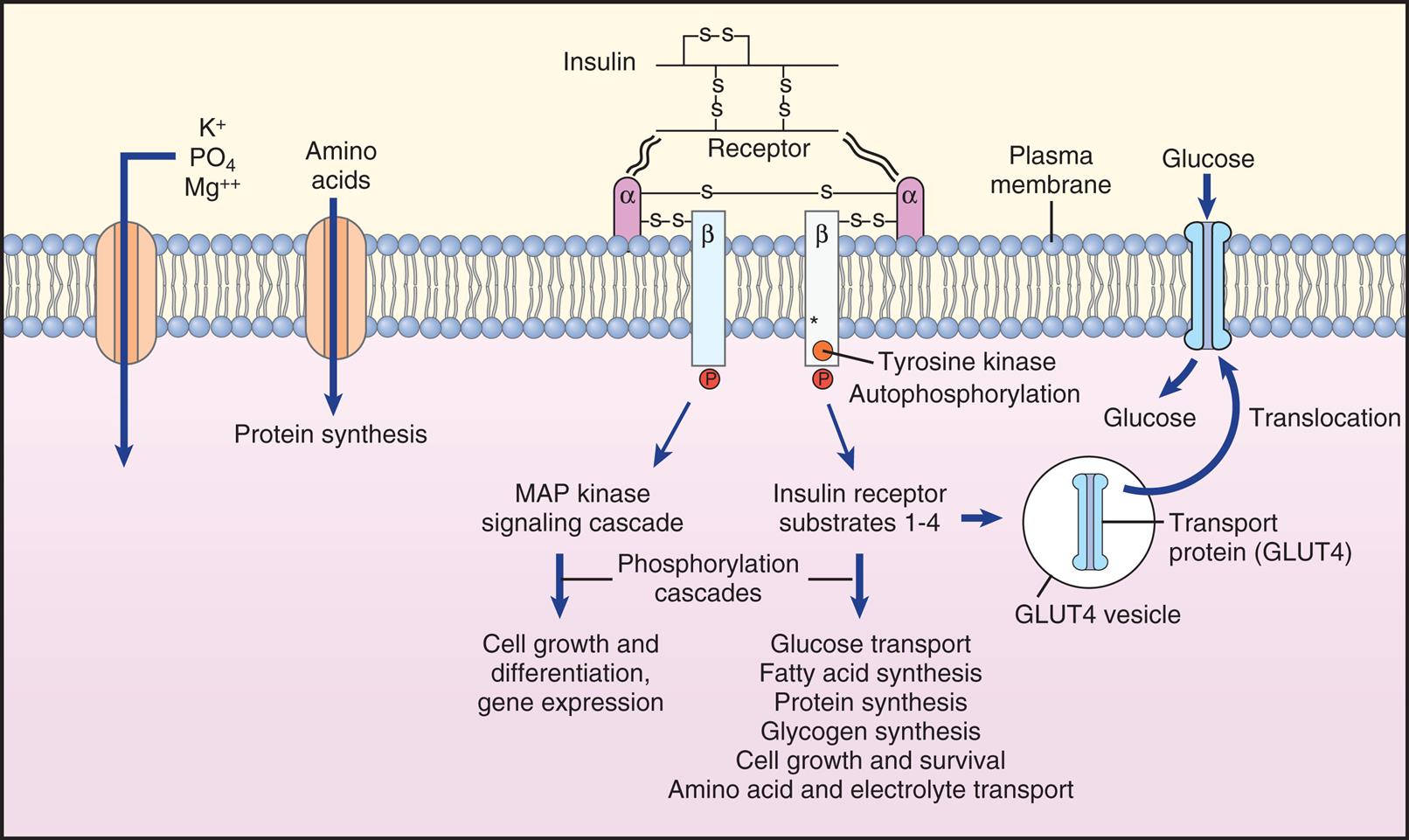

At the target cell, insulin signaling is initiated when insulin binds and activates its cell surface receptor tyrosine kinase. These receptors are found on cells throughout the body.4 Insulin receptor binding sends a cascade of signals to activate glucose transporters (GLUT) for entry of glucose into the cell. The primary GLUT is called GLUT4. It is stored in cellular vesicles until activated by the insulin receptor and is then translocated to the cell surface where it facilitates the diffusion of glucose into the cell. Translocation of GLUT4 to the cell surface is associated with a 10- to 21-fold increase in glucose diffusion into the cell, particularly in skeletal and cardiac muscle, liver, and adipose cells (Fig. 21.15). The brain, red blood cells, kidney, and lens of the eye do not require insulin for glucose transport.

Binding of insulin to its receptor causes autophosphorylation of the receptor, which then itself acts as a tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates insulin receptor substrates 1-4 (IRS-1-4). Numerous target enzymes, such as protein kinase B and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase, are activated, and these enzymes have a multitude of effects on cell function. The glucose transporter (GLUT4) is recruited to the plasma membrane, where it facilitates glucose entry into the cell. The transport of amino acids, potassium, magnesium, and phosphate into the cell is also facilitated. The synthesis of various enzymes is induced or suppressed, and cell growth is regulated by signal molecules that modulate gene expression. (Redrawn from Levy MN, Koeppen BM, Stanton BA, eds. Berne & Levy principles of physiology, 4th edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2006.)

An illustration shows a plasma membrane of lipid bilayers. Potassium ions, phosphate, and magnesium ions pass through an uniport and into the cell. Amino acids pass through a second uniport and undergo protein synthesis. Insulin is attached to the alpha receptors on the plasma membrane. Tyrosine kinase from the beta channels undergo autophosphorylation. M A P kinase signaling cascade, amplified by phosphorylation cascades, lead to cell growth and differentiation ang gene expression. Insulin receptor substrates 1 to 4, amplified by phosphorylation cascades, leading to the following: • Glucose transport. • Fatty acid synthesis. • Protein synthesis. • Glycogen synthesis. • Cell growth and survival. • Amino acid and electrolyte transport. Glucose passes through the transport protein (G L U T 4) in the G L U T 4 vesicle that translocate to the plasma membrane.

The sensitivity of the insulin receptor is a key component in maintaining normal cellular function. Insulin sensitivity is affected by age, weight, abdominal fat, and physical activity. Insulin resistance has been implicated in numerous diseases, including hypertension, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Adipocytes release a number of hormones and cytokines that are altered in obesity and have an important impact on insulin sensitivity (see Chapter 23). The most effective measures shown to improve insulin sensitivity in humans are weight loss and exercise.

Amylin

Amylin (or islet amyloid polypeptide) is a peptide hormone co-secreted with insulin by beta cells in response to nutrient stimuli. It regulates blood glucose concentration by delaying gastric emptying and suppressing glucagon secretion after meals. Amylin also has a satiety effect, which reduces food intake. Through these mechanisms, amylin works with insulin to prevent hyperglycemia.

Glucagon

Glucagon is antagonistic to the effects of insulin, acting to increase blood glucose during fasting, exercise, and hypoglycemia. Glucagon release is stimulated by low glucose levels and sympathetic stimulation and is inhibited by high glucose levels. Amino acids, such as alanine, glycine, and asparagine, also stimulate glucagon secretion. A protein-rich meal has the same effect. Glucagon is produced by the alpha cells of the pancreas and by cells lining the gastrointestinal tract. Glucagon acts primarily in the liver and increases the blood glucose concentration by stimulating glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis in muscle and lipolysis in adipose tissue. The lypolysis has a ketogenic effect caused by the metabolism of free fatty acids in the liver. These effects have led to the hypothesis that increased glucagon secretion is as important as insulin insufficiency in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus.14

Pancreatic Somatostatin

Pancreatic somatostatin is produced by delta cells of the pancreas in response to food intake and is essential in carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism. It is different from hypothalamic somatostatin, which inhibits the release of GH and TSH. Pancreatic somatostatin is involved in regulating alpha-cell and beta-cell function within the islets by inhibiting secretion of insulin, glucagon, and pancreatic polypeptide.

Incretins

The incretin hormones are secreted from endocrine cells in the gastrointestinal tract in the presence of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. The incretin hormones control postprandial glucose levels by promoting glucose-dependent insulin secretion, inhibiting glucagon synthesis, promoting hepatic glucose secretion, and delaying gastric emptying. Incretins also enhance beta-cell mass and replenish intracellular stores of insulin. Gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) are incretin hormones.

Gastrin, Ghrelin, and Pancreatic Polypeptide

Pancreatic gastrin stimulates the secretion of gastric acid. It is postulated that fetal pancreatic gastrin secretion is necessary for adequate islet cell development. Ghrelin stimulates GH secretion, controls appetite, and plays a role in obesity and the regulation of insulin sensitivity. Pancreatic polypeptide is released in response to hypoglycemia and protein-rich meals. It decreases pancreatic secretion of fluid and bicarbonate, promotes gastric secretion, antagonizes cholecystokinin, and is frequently increased in pancreatic tumors and in diabetes.15

Adrenal Glands

The adrenal glands are paired, pyramid-shaped organs behind the peritoneum and close to the upper pole of each kidney (see Fig. 21.1). Each gland is surrounded by a capsule, embedded in fat, and well supplied with blood from the aorta and phrenic and renal arteries. Venous return from the left adrenal gland is to the renal vein, and from the right adrenal gland is to the inferior vena cava.

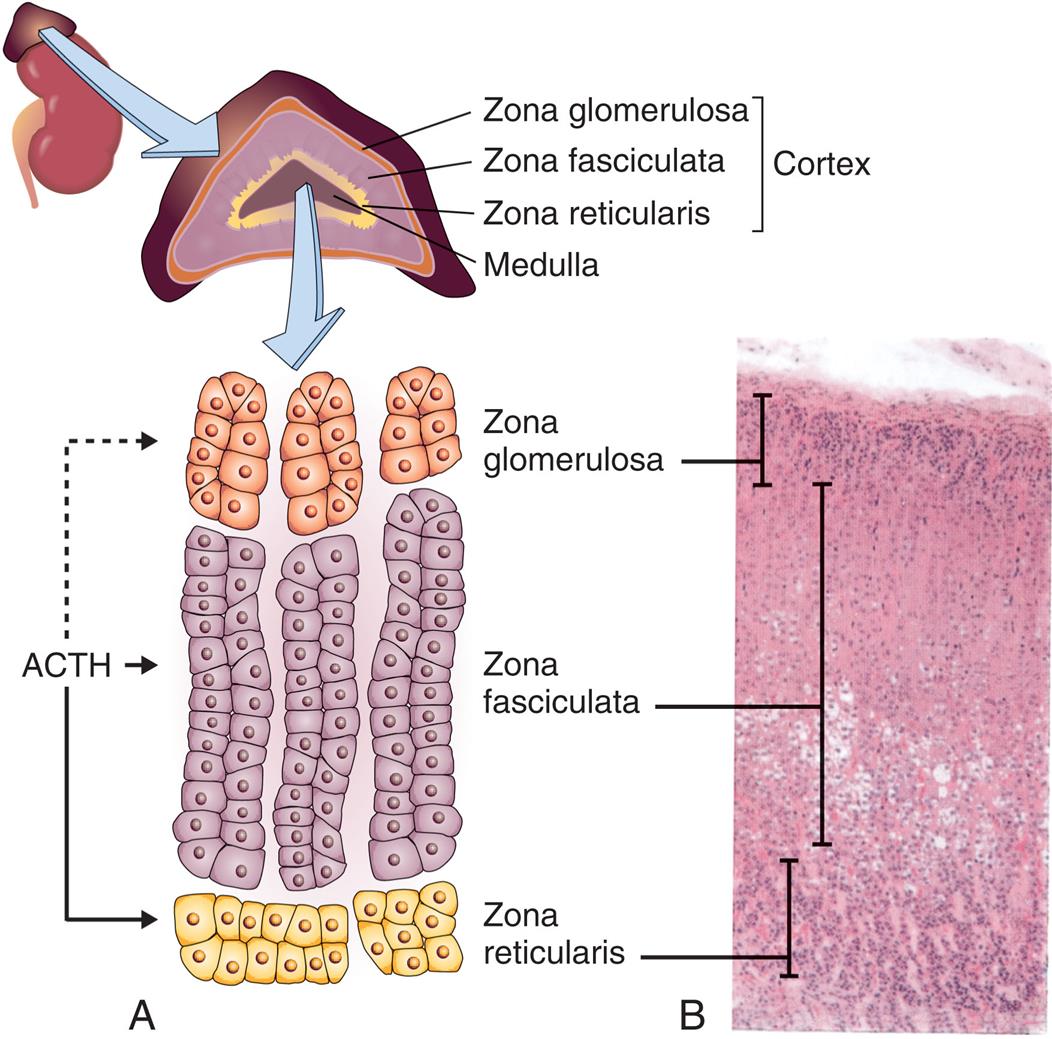

Each adrenal gland consists of two separate portions—an outer cortex and an inner medulla. These two portions have different embryonic origins, structures, and hormonal functions. The adrenal cortex and medulla function like two separate but interrelated glands (Fig. 21.16).

(A) Adrenal glands. Each gland consists of a cortex and a medulla. The cortex has three layers: zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculata, and zona reticularis. (B) A portion of the medulla is visible at the lower right in the photomicrograph (×35) and at the bottom of the drawing. ACTH, Adrenocorticotropic hormone. (A, From Damjanov I. Pathophysiology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008; B, From Kierszenbaum A. Histology and cell biology. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002.)

Illustration A of the adrenal glands shows and labels the following structures of the cortex: A C T H, zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculata, zona reticularis, and medulla. Photomicrograph B shows the following layers of the cortex, from the top to the bottom: zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculata, and zona reticularis.

Adrenal Cortex

The adrenal cortex accounts for 80% of the weight of the adult gland. The cortex is histologically subdivided into the following three zones:

- 1. The zona glomerulosa, the outer layer, constitutes about 15% of the cortex and primarily produces the mineralocorticoid aldosterone.

- 2. The zona fasciculata, the middle layer, constitutes 78% of the cortex and secretes the glucocorticoids cortisol, cortisone, and corticosterone.

- 3. The zona reticularis, the inner layer, constitutes 7% of the cortex and secretes mineralocorticoids (aldosterone), adrenal androgens and estrogens, and glucocorticoids.

The cells of the adrenal cortex are stimulated by ACTH from the pituitary gland. All hormones of the adrenal cortex are synthesized from low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. The best-known pathway of steroidogenesis involves the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone, which is then converted to the major corticosteroids.

Glucocorticoids

Functions of the glucocorticoids

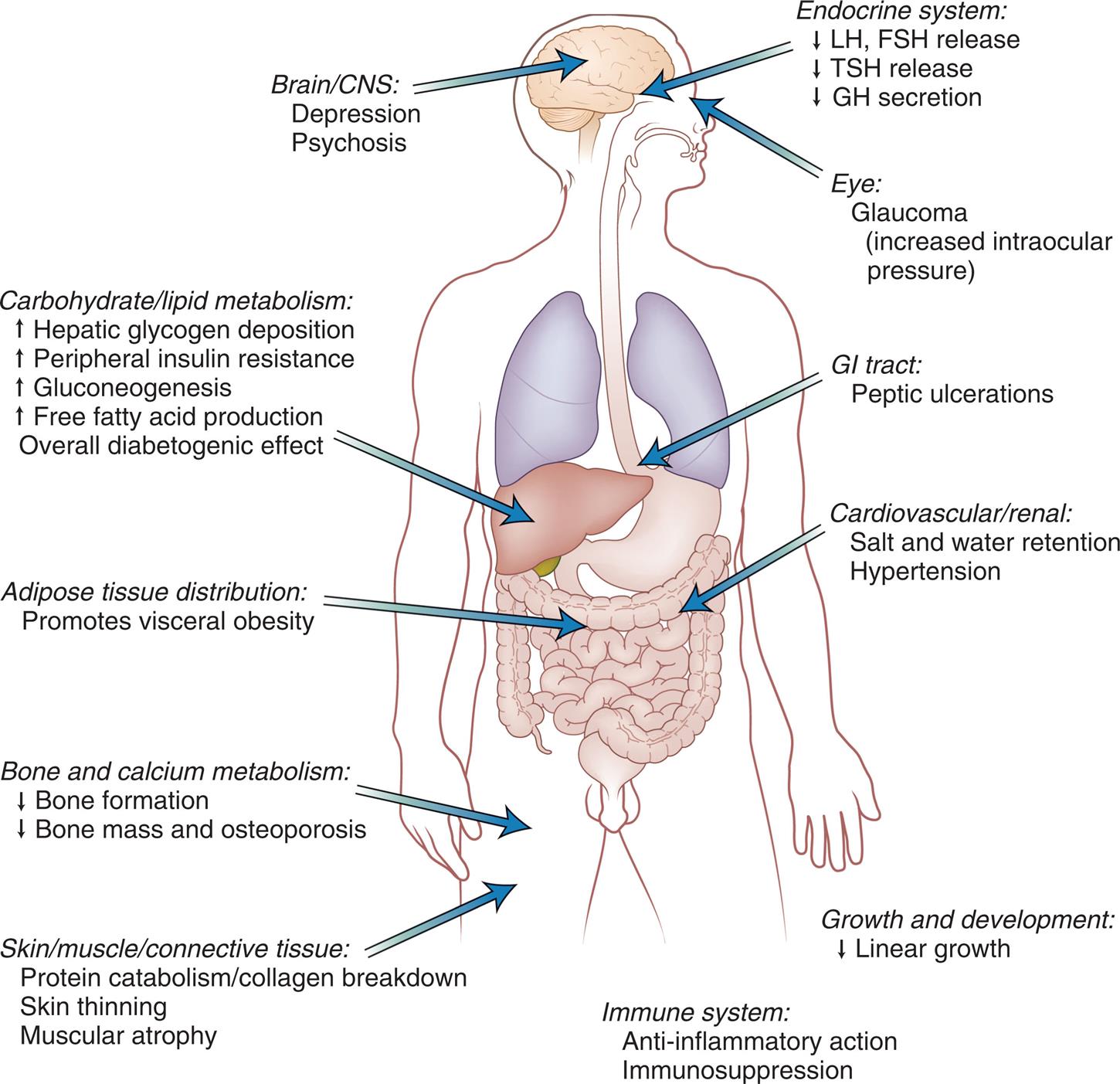

The glucocorticoids are steroid hormones that have metabolic, neurologic, anti-inflammatory, and growth-suppressing effects (Fig. 21.17). These functions have direct effects on carbohydrate metabolism. These hormones increase the blood glucose concentration by promoting gluconeogenesis in the liver and by decreasing uptake of glucose into muscle cells, adipose cells, and lymphatic cells and by suppressing insulin secretion. They are released under stress conditions, which results in increased glucose for the brain.34 In extrahepatic tissues, the glucocorticoids stimulate protein catabolism and inhibit amino acid uptake and protein synthesis. In extrahepatic tissues, the glucocorticoids stimulate protein catabolism and inhibit amino acid uptake and protein synthesis. The ultimate long-term effect of chronic stress on the body is protein catabolism and muscle wasting, increased lipolysis, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia.16

CNS, Central nervous system; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GH, growth hormone; GI, gastrointestinal; LH, Luteinizing hormone; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone. (From Stewart PM, Krone NP. The adrenal cortex. In: Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, et al., eds. Williams textbook of endocrinology, 12th edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2011.)

An illustration of the anterior view of a human figure shows and labels its different parts with corresponding effects. • Brain and C N S: depression and psychosis. • Endocrine system: decreased L H and F S H release, decreased T S H release, and decreased G H secretion. • Eye: Glaucoma (increased intraocular pressure). • G I tract: peptic ulcerations. • Carbohydrate or lipid metabolism: increased hepatic glycogen deposition, increased peripheral insulin resistance, increased glucogenesis, increased free fatty acid production, and overall diabetogenic effect. • Cardiovascular or renal: salt and water retention and hypertension. • Adipose tissue distribution: promotes visceral obesity. • Bone and calcium metabolism: decreased bone formation and decreased bone mass and osteoporosis. • Skin or muscle or connective tissue: protein catabolism or collagen breakdown, skin thinning, and muscular atrophy. • Growth and development: decreased linear growth. • Immune system: anti-inflammatory action and immunosuppression.

The glucocorticoids act at several sites to suppress immune and inflammatory reactions. Adaptive immunity is affected by a glucocorticoid-mediated inhibitory effect on the proliferation of T lymphocytes, primarily T-helper lymphocytes. There is a greater adverse effect on T-helper 1 cell cytokine production (including antiviral interferons) than there is on T-helper 2 cell cytokine production, and therefore, greater depression of cellular immunity than humoral immunity (see Chapter 8). They affect innate immunity through several pathways, including inhibition of antigen presentation by dendritic cells and decreased activity of pattern recognition receptors on the surface of macrophages (see Chapter 7). Glucocorticoids also decrease immune and inflammatory responses by decreasing natural killer cell activity; by blocking phospholipase A and the synthesis of prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes; and by inhibiting inflammatory gene expression. In addition, glucocorticoids suppress the synthesis, secretion, and actions of chemical mediators involved in inflammatory and immune responses, including histamine, adhesion molecules, inducible cyclooxygenase, and inducible nitric oxide synthase.17

Glucocorticoids increase resistance to the severe inflammatory response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS, a bacterial endotoxin) through the inhibition of cytokines, chemokines, certain hormones, and neurotransmitters. In addition, glucocorticoids stimulate anti-inflammatory cytokines. Lysosomal membranes are also stabilized, decreasing the release of proteolytic enzymes. This suppression of innate and adaptive immunity by glucocorticoids means that infection and poor wound healing are some of the most problematic complications of the use of glucocorticoids in the treatment of disease. Similarly, psychologic and physiologic stress increases glucocorticoid production, which provides a pathway for the well-described decrease in immunity seen in both acute and chronic stress conditions (see Chapter 11).18,19

Glucocorticoids appear to potentiate the effects of catecholamines, including sensitizing the arterioles to the vasoconstrictive effects of norepinephrine, thus increasing the blood pressure. Thyroid hormone and GH effects on adipose tissue are also potentiated by glucocorticoids. Other effects of glucocorticoids include inhibition of bone formation, inhibition of ADH secretion, and stimulation of gastric acid secretion. A metabolite of cortisol may act like a barbiturate and depress nerve cell function in the brain, accounting for the noted effects on mood, such as anxiety and depression, associated with steroid level fluctuation in disease or stress. Pathologically high levels of glucocorticoids increase the number of circulating erythrocytes (leading to polycythemia), increase the appetite, promote fat deposition in the face and cervical areas, increase uric acid excretion, decrease serum calcium levels, suppress the secretion and synthesis of ACTH, and interfere with the action of GH so that somatic growth is inhibited.20

Cortisol

The most potent naturally occurring glucocorticoid is cortisol. It is the main secretory product of the adrenal cortex and is needed to maintain life and protect the body from stress (see Fig. 11.2). Cortisol circulates in bound form attached to albumin but is primarily bound to the plasma protein transcortin. A smaller amount circulates in free form and diffuses into cells with specific intracellular receptors for cortisol. Cortisol has a biologic half-life of approximately 90 minutes. It is primarily metabolized by the liver.

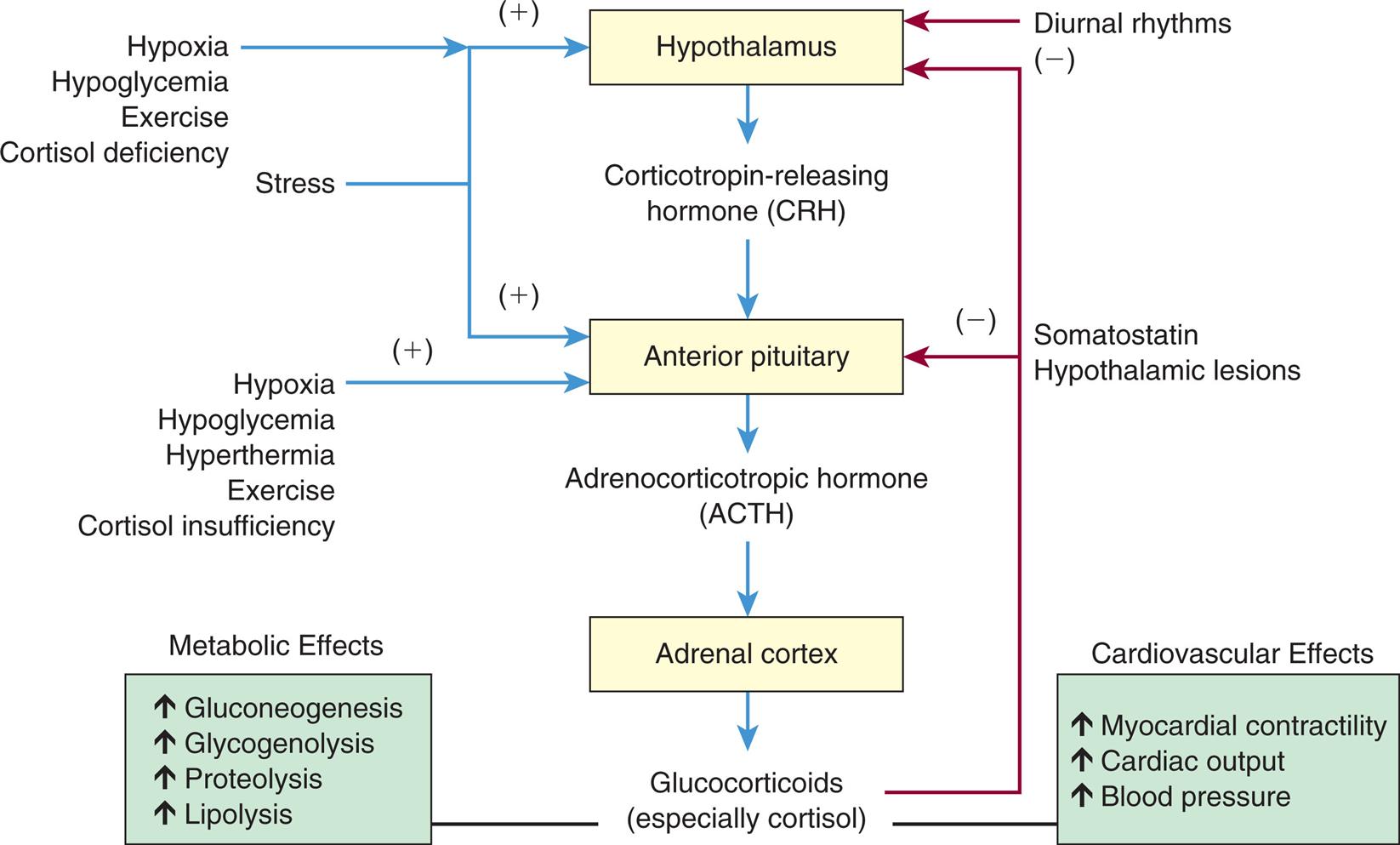

Cortisol secretion is regulated primarily by the hypothalamus and the anterior pituitary gland (Fig. 21.18). Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is produced by several nuclei in the hypothalamus and stored in the median eminence. Once released, CRH travels through the portal vessels to stimulate the production of ACTH, which is the main regulator of cortisol secretion.

A flowchart shows the feedback control of glucocorticoid synthesis and secretion. The hypothalamus generates corticotropin-releasing hormone (C R H), triggering the anterior pituitary. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (A C T H) from the anterior pituitary triggers the adrenal cortex. Glucocorticoids (especially cortisol) from the adrenal cortex results in the following effects. • Metabolic effects: increased gluconeogenesis, increased glycogenolysis, increased proteolysis, and increased lipolysis. • Cardiovascular effects: increased myocardial contractility, increased cardiac output, and increased blood pressure. The feedback mechanisms are as follows. • Hypothalamus receives positive feedback from hypoxia, hypoglycemia, exercise, cortisol deficiency, and stress. • Hypothalamus receives negative feedback from diurnal rhythms, somatostatin, hypothalamic lesions, and glucocorticoids. • Anterior pituitary receives positive feedback from hypoxia, hypoglycemia, hyperthermia, exercise, cortisol insufficiency, and stress. • Anterior pituitary receives negative feedback from somatostatin, hypothalamic lesions, and glucocorticoids.

Three factors appear to be primarily involved in regulating the secretion of ACTH: (1) negative-feedback effects of high circulating levels of cortisol; (2) diurnal rhythms, with peak levels during sleep; and (3) psychological and physiologic stress increases ACTH secretion, leading to increased cortisol levels. (Neurologic mechanisms regulating sleep are discussed in Chapter 16.)

There also is evidence that there is synthesis and secretion of glucocorticoids from extra-adrenal tissue including the thymus, lung, intestine, skin, brain, and possibly heart in response to immune stimulation. This is thought to provide autocrine and paracrine immune regulation and control of inflammation. Dysregulation of extra-adrenal glucocorticoid production can contribute to autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.21

Once ACTH is secreted, it binds to specific plasma membrane receptors on the cells of the adrenal cortex and on other extra-adrenal tissues. Because both adrenal and extra-adrenal tissues have ACTH receptors, a number of effects result from stimulation by ACTH (Box 21.1). ACTH stimulates the cells of the adrenal cortex to immediately synthesize and secrete cortisol. In healthy people, the secretory patterns of ACTH and cortisol are nearly identical. After secretion, 10% to 15% of cortisol circulates unbound, while the rest is bound to albumin or a plasma glycoprotein called transcortin. The levels of transcortin play a role in the HPA feedback system controlling cortisol secretion. Transcortin levels are significantly elevated by increased estrogen levels that occur with pregnancy and hormone therapy. The unbound portion is free to diffuse into cells, but only those cells with specific intracellular glucocorticoid receptors respond to cortisol stimulation. ACTH is rapidly inactivated in the circulation, and the liver and kidneys eliminate the deactivated hormone.

Mineralocorticoids: aldosterone

Mineralocorticoid steroids directly affect ion transport by epithelial cells, causing sodium retention and potassium and hydrogen loss. Aldosterone is the most potent naturally occurring mineralocorticoid and conserves sodium by increasing the activity of the sodium pump of epithelial cells in the nephron. (The sodium pump is described in Chapter 1.)

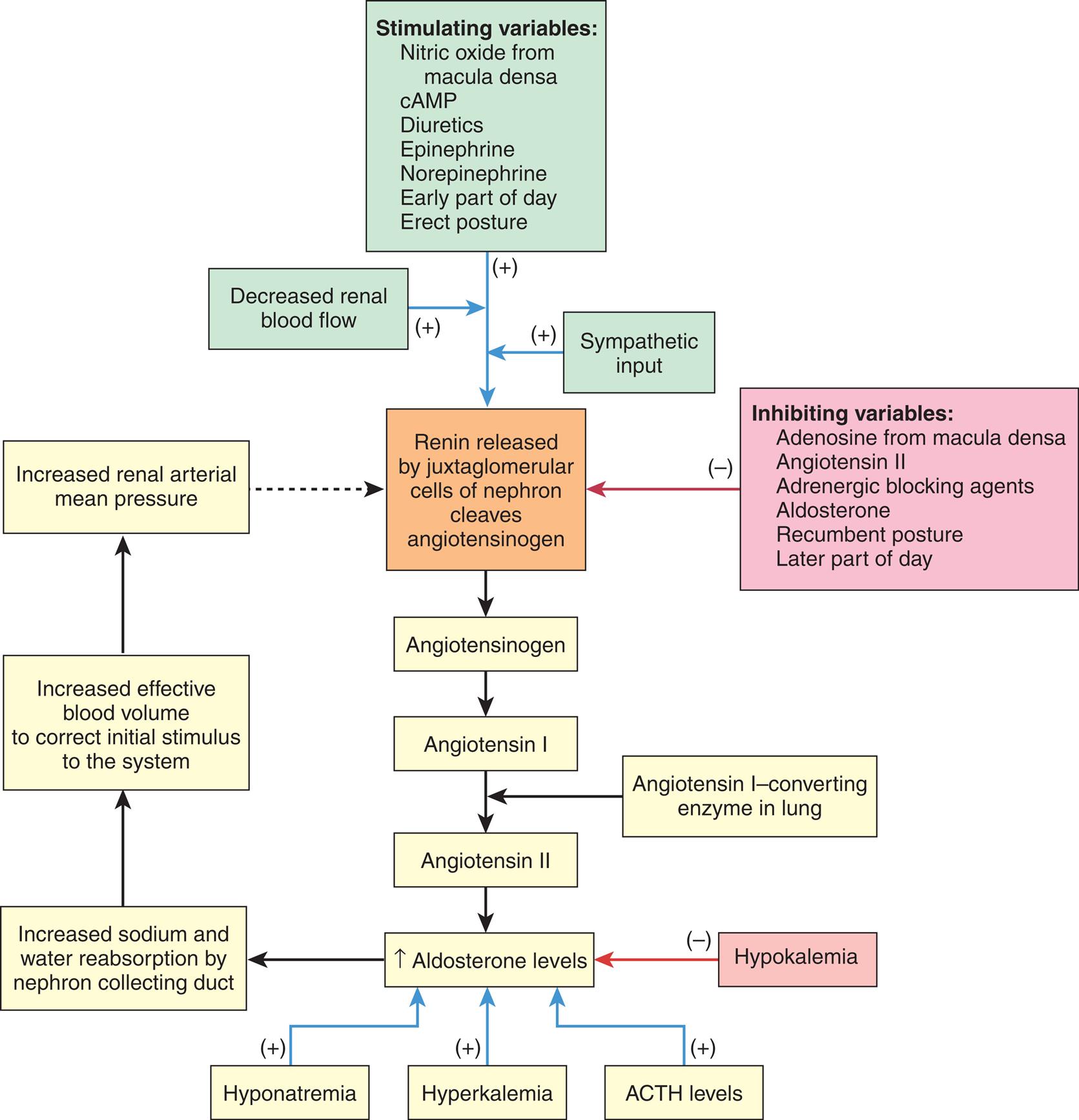

The initial stages of aldosterone synthesis occur in the adrenal zona fasciculata and zona reticularis. The final conversion of corticosterone to aldosterone occurs in the zona glomerulosa. Aldosterone synthesis and secretion is regulated primarily by the renin-angiotensin system (described in Chapter 37). The renin-angiotensin system is activated by sodium and water depletion, increased potassium levels, and a diminished effective blood volume (Fig. 21.19). Angiotensin II is the primary stimulant of aldosterone synthesis and secretion; however, sodium and potassium levels also may directly affect aldosterone secretion. ACTH acutely stimulates aldosterone secretion but is secondary to angiotensin II and potassium.

ACTH, Adrenocorticotropic hormone; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

A flowchart shows the feedback mechanisms in regulating aldosterone secretion. The general loop in the regulating process I as follows. • Renin released by juxtaglomerular cells of nephron cleaves angiotensinogen. • Angiotensinogen. • Angiotensin 1. • Angiotensin 2 (also from angiotensin 1-converting enzyme in lung). • Increased aldosterone levels. • Increased sodium and water reabsorption by nephron collecting duct. • Increased effective blood volume to correct initial stimulus to the system. • Increased renal arterial mean pressure. The positive feedback mechanisms impacting the first stage of the regulation are as follows. • Stimulating variables: nitric oxide from macula densa, c A M P, diuretics, epinephrine, norepinephrine, early part of day, and erect posture. • Decreased renal blood flow. • Sympathetic input. The negative feedback mechanisms (inhibiting variables) impacting the first stage of the regulation are as follows. • Adenosine from macula densa. • Angiotensin 2. • Adrenergic blocking agents. • Aldosterone. • Recumbent posture. • Later part of day. The positive feedback mechanisms impacting the increased aldosterone levels are as follows. • Hyponatremia. • Hyperkalemia. • A C T H levels. Hypokalemia is the negative feedback mechanisms impacting the increased aldosterone levels.

When sodium and potassium levels are within normal limits, approximately 50 to 250 mg of aldosterone is secreted daily. Of the secreted aldosterone, 50% to 75% binds to plasma proteins. The proportion of unbound aldosterone contributes to its rapid metabolic turnover in the liver, its low plasma concentration, and its short half-life (about 15 minutes). Aldosterone is metabolized in the liver and is excreted by the kidney.

Aldosterone maintains extracellular volume and blood pressure by acting on distal nephron epithelial cells to increase reabsorption of sodium and excretion of potassium and hydrogen. This renal effect takes 90 minutes to 6 hours. Fluid and electrolyte regulation is addressed in more detail in Chapter 3. Other effects of aldosterone include enhancement of cardiac muscle contraction, stimulation of ectopic ventricular activity through secondary cardiac pacemakers in the ventricles, stiffening of blood vessels with increased vascular resistance, and decrease in fibrinolysis. Pathologically elevated levels of aldosterone have been implicated in the myocardial changes associated with heart failure.22

Adrenal estrogens and androgens

The healthy adrenal cortex secretes minimal amounts of estrogen and androgens. ACTH appears to be the major regulator. Some of the weakly androgenic substances secreted by the cortex (dehydroepiandrosterone [DHEA], androstenedione) are converted by peripheral tissues to stronger androgens, such as testosterone, thus accounting for some androgenic effects initiated by the adrenal cortex. Peripheral conversion of adrenal androgens to estrogens is enhanced in aging or obese persons, as well as in those with liver disease or hyperthyroidism. The biologic effects and metabolism of the adrenal sex steroids do not vary from those produced by the gonads (see Chapter 24).

Adrenal Medulla

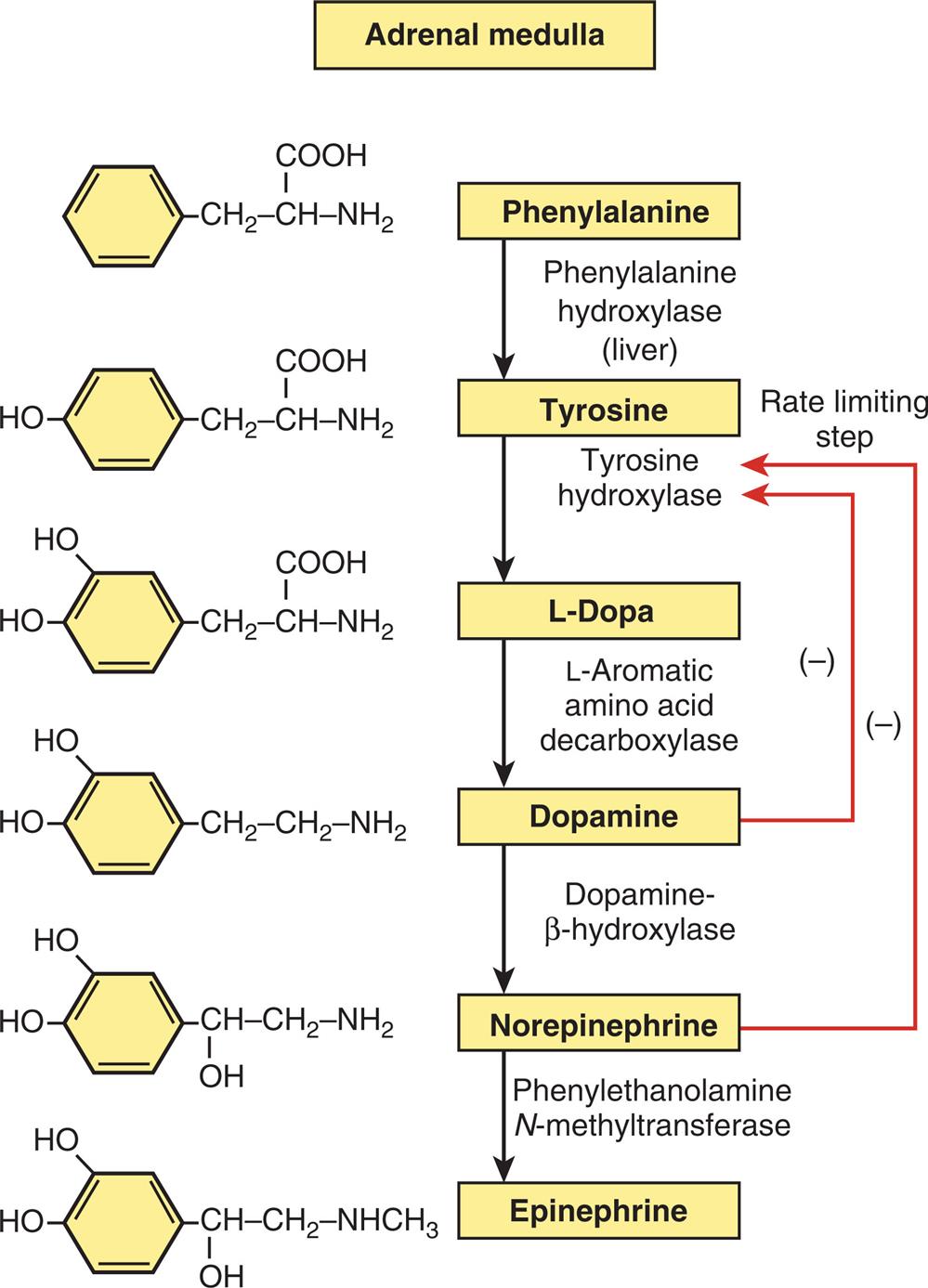

The adrenal medulla, together with the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system, is embryonically derived from neural crest cells. The chromaffin cells (pheochromocytes) of the adrenal medulla secrete and store the catecholamines epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline). Both are synthesized from the amino acid phenylalanine (Fig. 21.20). Only 30% of circulating epinephrine comes from the adrenal medulla (the other 70% is released from nerve terminals), and the medulla is only a minor source of norepinephrine. The adrenal medulla functions as a sympathetic ganglion without postganglionic processes. Sympathetic cholinergic preganglion fibers terminate on the chromaffin cells and secrete catecholamines directly into the bloodstream. The catecholamines acting in the blood are therefore hormones and not neurotransmitters.

An illustration depicts the pathway of catecholamine biosynthesis accompanied by the chemical structures of the compounds. 1. Phenylalanine converted to tyrosine by hydroxylase. 2. Tyrosine is converted to Dopa by hydroxylase. 3. Dopa is converted to Dopamine by beta-hydroxylase. 4. Dopamine is converted to norepinephrine by N-methyltransferase. 5. Norepinephrine is converted to epinephrine. 6. The rate-limiting step is indicated by the sublimation of dopamine and norepinephrine by tyrosine hydroxylase.

Physiologic stress to the body (e.g., traumatic injury, hypoxia, hypoglycemia) triggers the exocytosis of the storage granules from chromaffin cells, with release of epinephrine and norepinephrine into the bloodstream. Secretion of adrenal catecholamines is also increased by ACTH and the glucocorticoids. Once released, the catecholamines remain in the plasma for only seconds to minutes. The catecholamines exert their biologic effects after binding to plasma membrane receptors (α1, α2, β1, β2, and β3) in target cells. This binding activates the adenylyl cyclase system (an intracellular second messenger system). Catecholamines have diverse effects on the entire body. Their release and the body's response have been characterized as the “fight or flight” response (stress response) (see Figs. 11.2 and 11.4 and Tables 11.3 and 11.4). Metabolic effects of catecholamines promote hyperglycemia through a variety of mechanisms, including interference with the usual glucose regulatory feedback mechanisms. Catecholamines are rapidly removed from the plasma by neuron absorption for storage in new cytoplasmic granules, or metabolically inactivated and excreted in the urine. Catecholamines also directly inhibit secretion by decreasing the formation of the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (the rate-limiting step, see Fig. 21.20).

Tests of Endocrine Function

Evaluation of the endocrine system is challenging because of (1) the complexity of the clinical presentation as a result of multiple organ system involvement, (2) the nonspecific nature of complaints frequently associated with endocrine dysfunction, and (3) the inappropriate use of laboratory test interpretations.

Tests of the endocrine system involve several general types of clinical evaluation. Measurement of hormone level is accomplished by RIA, by ELISA, and, less commonly, by bioassay. Radioimmunoassay (RIA), a technique for measuring the minute quantities of hormones in the blood, uses antibodies and radiolabeled hormones to determine the quantity of hormone in the plasma. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) also is used to determine circulating hormone levels. This method is similar to that of RIA but is less expensive and easier to conduct. Instead of radiolabeled hormones, an enzyme-labeled hormone is used. A bioassay involves the use of graded doses of hormone in a reference preparation and then comparison of the results with an unknown sample. Bioassays are used more commonly in investigative endocrinology than in clinical laboratories. If the serum level is greater or less than the reference values, more definitive tests are required to determine the source of the problem.

Measurement of individual hormones does not always permit differentiation between normal and abnormal values when hormone levels are changing over time. For an accurate interpretation, the broad normal range of some hormones requires knowledge of previous hormonal levels and timed sampling. Stimulation and suppression tests that determine the response to exogenous stimulants or inhibitors can help to decipher some of these complexities.

Indirect assessment of hormonal function often includes measurement of concentrations of serum glucose and electrolytes that are affected by the endocrine process. Evaluation of hormonal function also may include radiographic imaging of specific glands.

Aging and the Endocrine System

The precise relationship between aging and the endocrine system is not clear. Perhaps most important, the question of whether changes in endocrine function are a consequence or a cause of aging has yet to be resolved. These relationships have been difficult to identify, in part because of a number of age-related variables that may coexist, such as acute and chronic nonendocrine disease; use of medications; alterations in diet, body composition, and weight; and changes in sleep-wake cycles. However, the endocrine system is so integral to health that changes in endocrine function have been used as “biomarkers” for unhealthy aging.