Alterations of Hematologic Function

Sean McConnell and Valentina L. Brashers

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Rogers/pathophysiology/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Rogers/pathophysiology/

Alterations of erythrocyte function involve either insufficient or excessive numbers of erythrocytes in the circulation or normal numbers of cells with abnormal components. Anemias are conditions in which there are too few erythrocytes or an insufficient volume of erythrocytes in the blood. Polycythemias are conditions in which erythrocyte number or volume is excessive. Each of these conditions has many causes and shares pathophysiologic manifestations with other disease states.

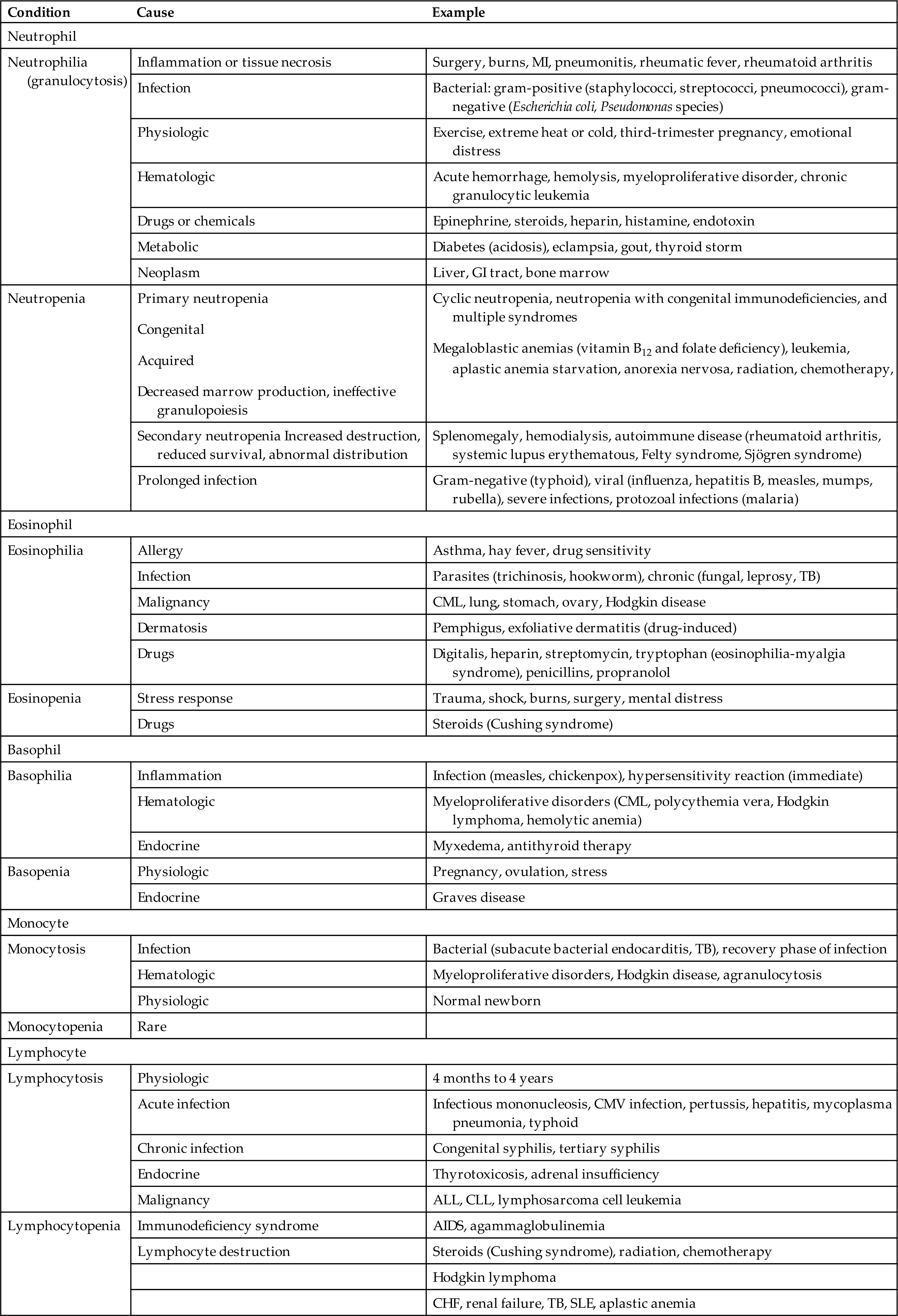

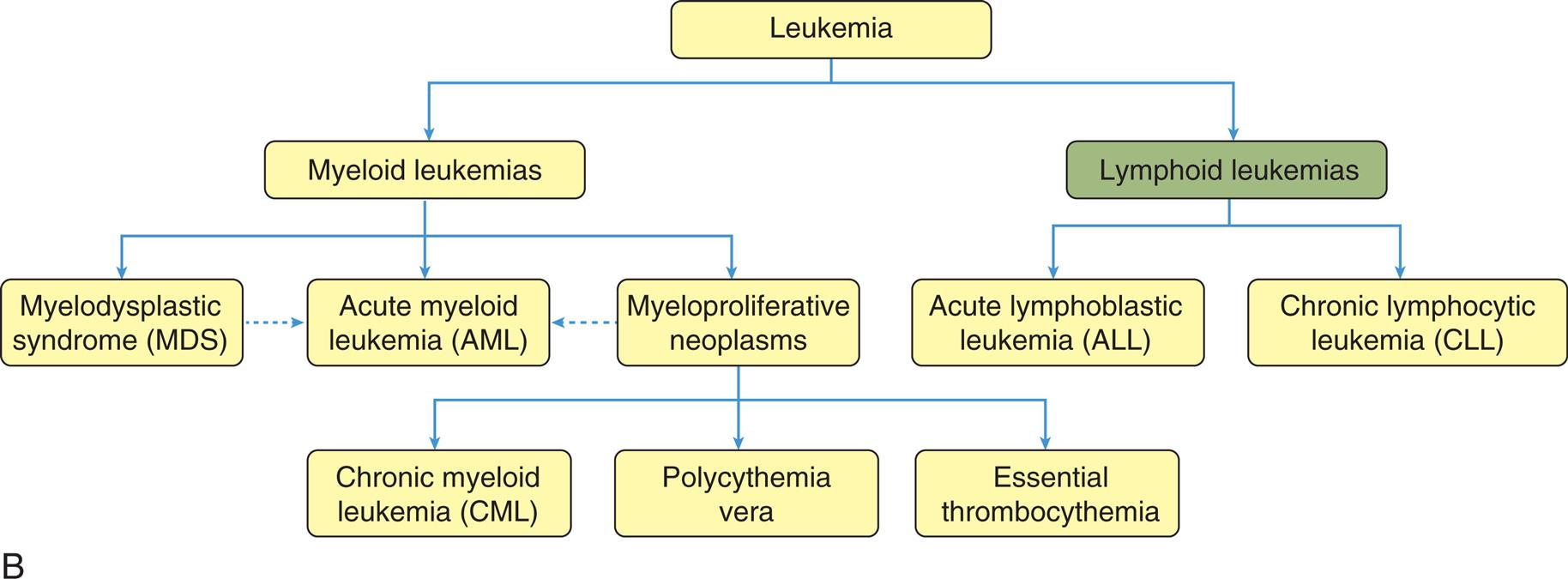

Disorders involving white blood cells (leukocytes) can range from increased numbers of leukocytes (leukocytosis) in response to infections, or proliferative disorders (e.g., leukemia), to decreased numbers of leukocytes (e.g., leukopenia). Many hematologic and nonhematologic malignancies metastasize to the bone marrow and affect leukocyte production. Thus, a large portion of this chapter is devoted to malignant disease.

The primary role of clotting (hemostasis) is to stop bleeding through an interaction of endothelium lining the vessels, platelets, and clotting factors. Several disease states increase or decrease clotting in at least one of the three main components of the clotting process.

Anemia

Classification and General Characteristics

Anemia is a reduction in the total number of erythrocytes in the circulating blood or a decrease in the quality or quantity of hemoglobin. The term anemia refers to a true decrease in erythrocyte number, rather than a relative decrease due to increases in plasma volume (hemodilution). The overall prevalence of anemia is approximately 10% to 15% of individuals in the United States affecting approximately 40% of men and 22% of women over the age of 85.1

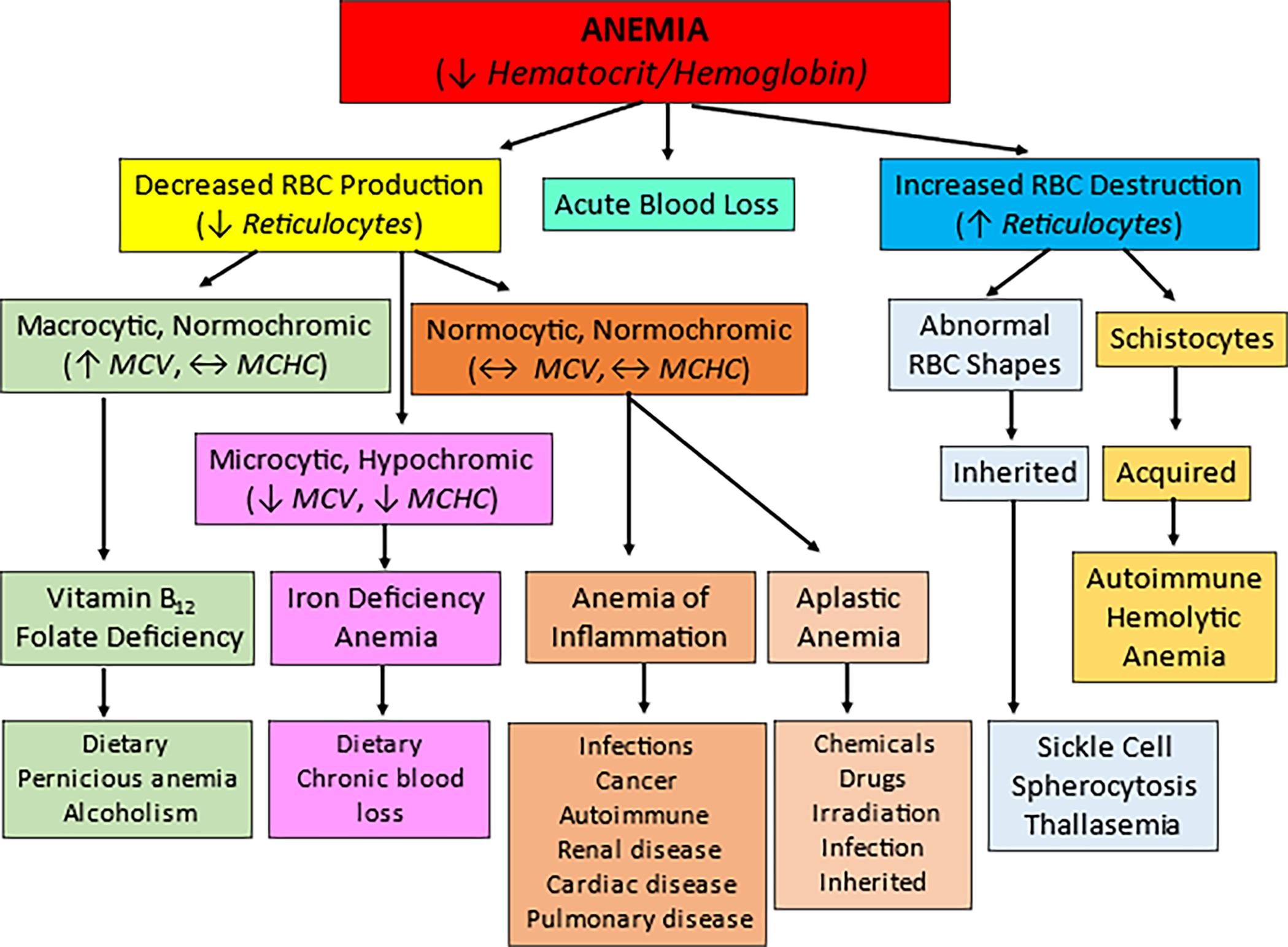

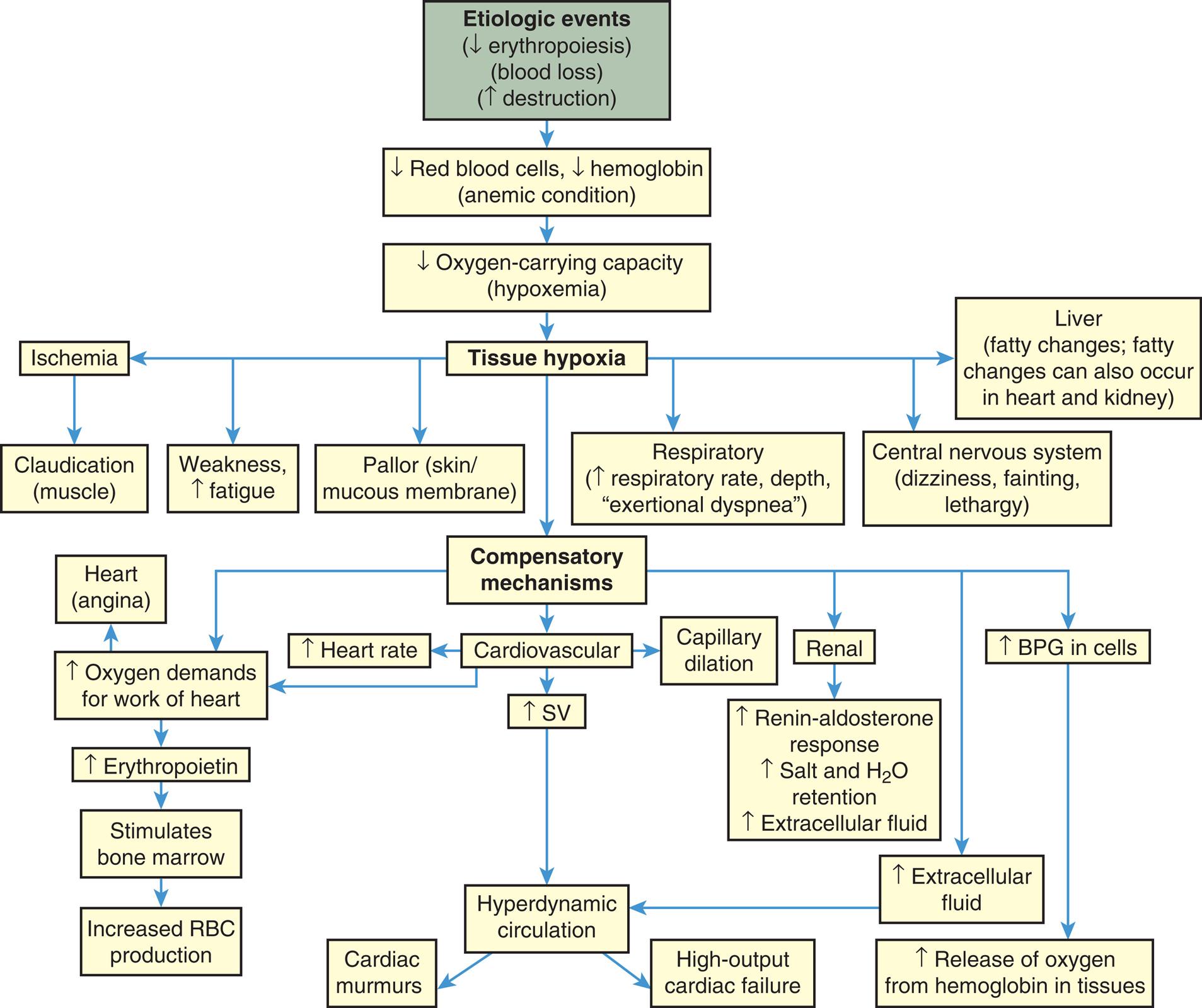

Anemias commonly result from (1) blood loss (acute or chronic), (2) impaired erythrocyte production, (3) increased erythrocyte destruction, or (4) a combination of these three factors (Fig. 29.1). Anemias are classified based on etiology (e.g., acute blood loss or anemia of inflammation [AI]) or by the changes that affect the size, shape, or substance of the erythrocyte. The most common classification of anemias is based on the changes that affect the cell's size and hemoglobin content (Table 29.1). Terms used to identify anemias reflect these characteristics. Terms that end with -cytic refer to cell size, and those that end with -chromic refer to hemoglobin content. Additional terms describing erythrocytes found in some anemias are anisocytosis (assuming various sizes) and poikilocytosis (assuming various shapes).

Anemias can be classified into three major categories: acute blood loss, decreased RBC production in which reticulocytes are decreased, and increased RBC destruction in which reticulocyte counts are increased. Further classification relies on the size (-cytic), color (-chromic), and shape of the cells. Based on these factors, the most common types and causes of anemia can be identified. MCHC, Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume.

A hierarchy chart represents the classification of anemia. 1. Anemia (decreased hematocrit or hemoglobin). Two classifications: 2 and 3. 2. Decreased R B C production (reduced reticulocytes). Three classifications: 5, 6, and 9. 3. Acute blood loss (equilibrium M C V, equilibrium M C H C). 4. Increased R B C destruction (reduced reticulocytes). Two classifications: 7 and 8. 5. Macrocytic; normochromic (increased M C V, equilibrium M C H C). One classification: 12. 6. Normocytic; normochromic (decreased M C V, decreased M C H C). Two classifications: 14 and 15. 7. Abnormal R B C shapes. One classification: 10. 8. Schistocytes. One classification: 11. 9. Macrocytic, hypochromic (equilibrium M C V, equilibrium M C H C). One classification: 13. 10. Inherited. One classification: 20. 11. Acquired. One classification: 21. 12. Vitamin B 12; folate deficiency. One classification: 16. 13. Iron deficiency; anemia. One classification: 17. 14. Anemia of inflammation. One classification: 18. 15. Aplastic anemia. One classification: 19. 16. Dietary; pernicious anemia; alcoholism. 17. Dietary; chronic blood loss. 18. Infections; cancer; autoimmune; renal disease; cardiac disease; pulmonary disease. 19. Chemicals; drugs; irradiation; infection; inherited. 20. Sickle cell; spherocytosis; thalassemia. 21. Autoimmune; hemolytic; anemia.

Table 29.1

Clinical Manifestations

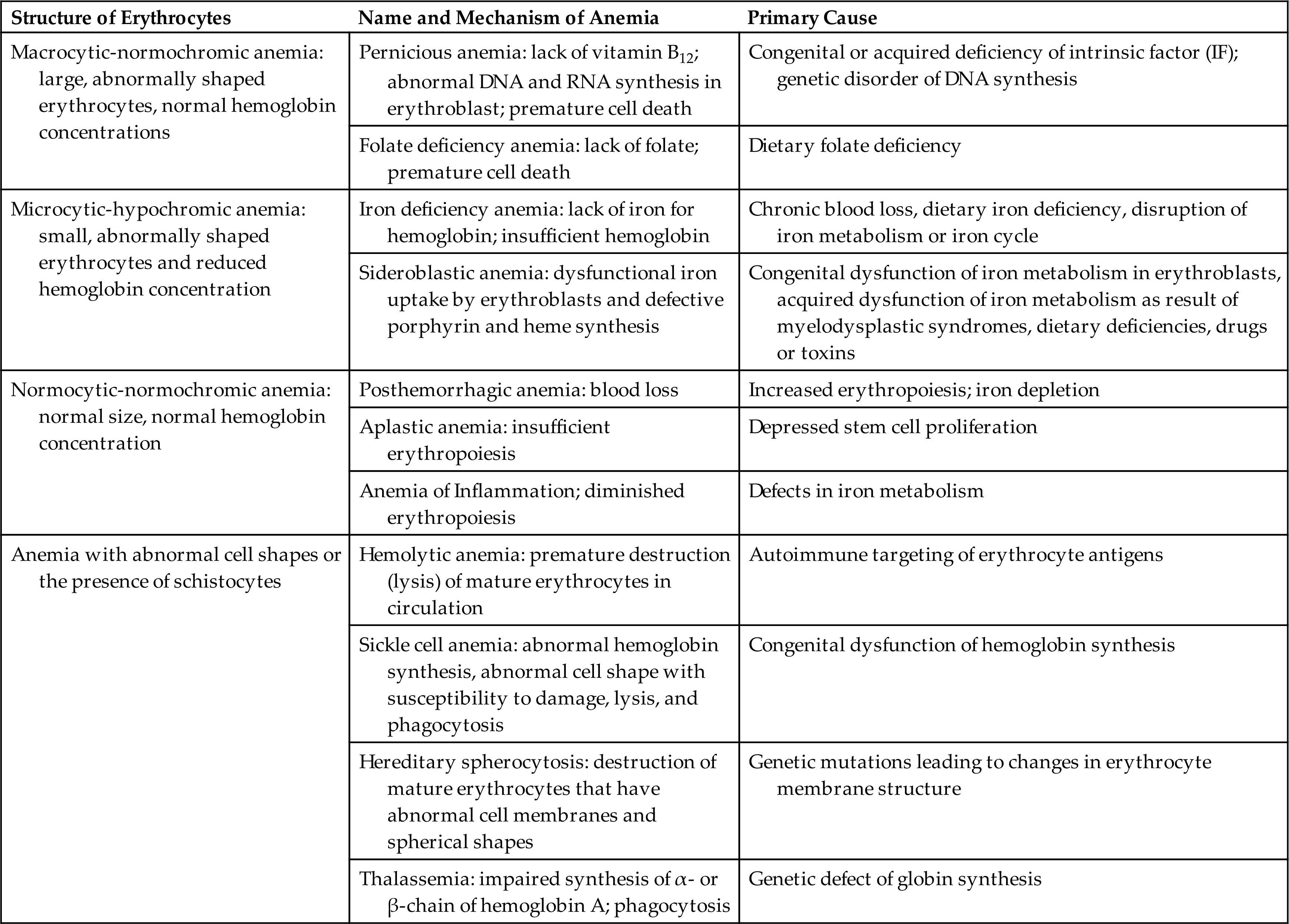

The main clinical effect of anemia is a reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood resulting in tissue hypoxia. Symptoms of anemia vary, depending on the body's ability to compensate for the reduced oxygen-carrying capacity. Anemia that is mild and starts gradually is usually easier to compensate and may cause problems for the individual only during physical exertion. As red cell reduction continues, symptoms become more pronounced and alterations in specific organs and compensation effects are more apparent. Compensation generally involves the cardiovascular, respiratory, and hematologic systems (Fig. 29.2).

BPG, Bisphosphoglycerate; SV, stroke volume.

A flowchart shows the progression and manifestations of anemia. 1. Etiologic events (decreased erythropoiesis, blood loss, increased destruction). Progresses to 2. 2. Decreased red blood cells, decreased hemoglobin (anemic condition). Progresses to 3. 3. Decreased oxygen-carrying capacity (hypoxemia). Progresses to 4. 4. Tissue hypoxia. Progresses to 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, and 11. 5. Ischemia. Progresses to 7. 6. Liver (fatty changes; fatty changes can also occur in heart and kidney). 7. Claudication (muscle). 8. Weakness (increased fatigue). 9. Pallor (skin or mucous membrane). 10. Respiratory (increased respiratory rate, depth, exertional dyspnea). 11. Central nervous system (dizziness, fainting, lethargy). 12. Compensatory mechanisms. Progresses to 14, 16, 18, 19, and 28. 13. Heart (angina). 14. Increased oxygen demands for work of heart. Progresses to 21. 15. Increased heart rate. 16. Cardiovascular. Progresses to 20. 17. Capillary dilation. 18. Renal. Progresses to 22. 19. Increased B P G in cells. Progresses to 29. 20. Increased S V. Progresses to 25. 21. Increased erythropoietin. Progresses to 22. 22. Increased renin-aldosterone response, increased salt and water extracellular fluid. 23. Stimulates bone marrow. Progresses to 24. 24. Increased R B C production. 25. Hyperdynamic circulation. Progresses to 26 and 27. 26. Cardiac murmurs. 27. High-output cardiac failure. 28. Increased extracellular fluid. Progresses to 25. 29. Increased release of oxygen from hemoglobin in tissues.

A reduction in the number of blood cells causes a reduction in the consistency and volume of blood. Initial compensation for cellular loss is movement of interstitial fluid into the blood, causing an increase in plasma volume. This movement maintains an adequate blood volume, but the viscosity (thickness) of the blood decreases. The “thinner” blood flows faster and more turbulently than normal blood, causing a hyperdynamic circulatory state. This hyperdynamic state creates cardiovascular changes—increased stroke volume and heart rate. These changes may lead to cardiac dilation and heart valve insufficiency if the underlying anemic condition is not corrected.

Hypoxemia, reduced oxygen level in the blood, further contributes to cardiovascular dysfunction by causing dilation of arterioles, capillaries, and venules in the systemic circulation, thus increasing flow through them. Increased peripheral blood flow and venous return further contributes to an increase in heart rate and stroke volume in a continuing effort to meet normal oxygen demand and prevent cardiopulmonary congestion. These compensatory mechanisms may lead to heart failure.

Tissue hypoxia creates additional demands and effects on the pulmonary and hematologic systems. The rate and depth of breathing increase, in an effort to increase oxygen availability, accompanied by an increase in the release of oxygen from hemoglobin (see Chapter 34). All these compensatory mechanisms may cause individuals to experience shortness of breath (dyspnea), a rapid and pounding heartbeat, dizziness, and fatigue. In mild chronic cases, these symptoms may be present only when there is an increased demand for oxygen (e.g., during physical exertion), but in severe cases, symptoms may be experienced even at rest.

Manifestations of anemia may be seen in other parts of the body. The skin, mucous membranes, lips, nail beds, and conjunctivae become either pale because of reduced hemoglobin concentration or yellowish (jaundiced) because of accumulation of end products of red cell destruction (hemolysis) if that is the cause of the anemia. Tissue hypoxia of the skin results in impaired healing and loss of elasticity, as well as thinning and early graying of the hair. Nervous system manifestations may occur in which the cause of anemia is a deficiency of vitamin B12. Myelin degeneration may occur, causing a loss of nerve fibers in the spinal cord, resulting in paresthesia (numbness), gait disturbances, extreme weakness, spasticity, and reflex abnormalities. Decreased oxygen supply to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract often produces abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia. Low-grade fever (<101°F [38.3°C]) occurs in some anemic individuals and may result from the release of inflammatory pyrogens from ischemic tissues.

When the onset of anemia is severe or acute (e.g., hemorrhage), the initial compensatory mechanism is peripheral blood vessel constriction, which diverts blood flow to essential vital organs. Decreased blood flow detected by the kidneys activates the renin-angiotensin response, causing salt and water retention in an attempt to increase blood volume (see Chapters 31 and 37). These situations are emergencies and require immediate intervention to correct the underlying problem that caused the acute blood loss; therefore, long-term compensatory mechanisms do not develop.

Therapeutic interventions for slowly developing anemic conditions should focus on treatment of the underlying condition with improvement of associated symptoms. Therapies include dietary correction, administration of supplemental vitamins or iron, removal of toxic agents (e.g., drugs), and interventions that are directed at treating hemolytic conditions (e.g., sickle cell disease). Transfusion therapy is used when anemia is severe and cannot be reversed quickly.

Anemias of Blood Loss

Acute Blood Loss

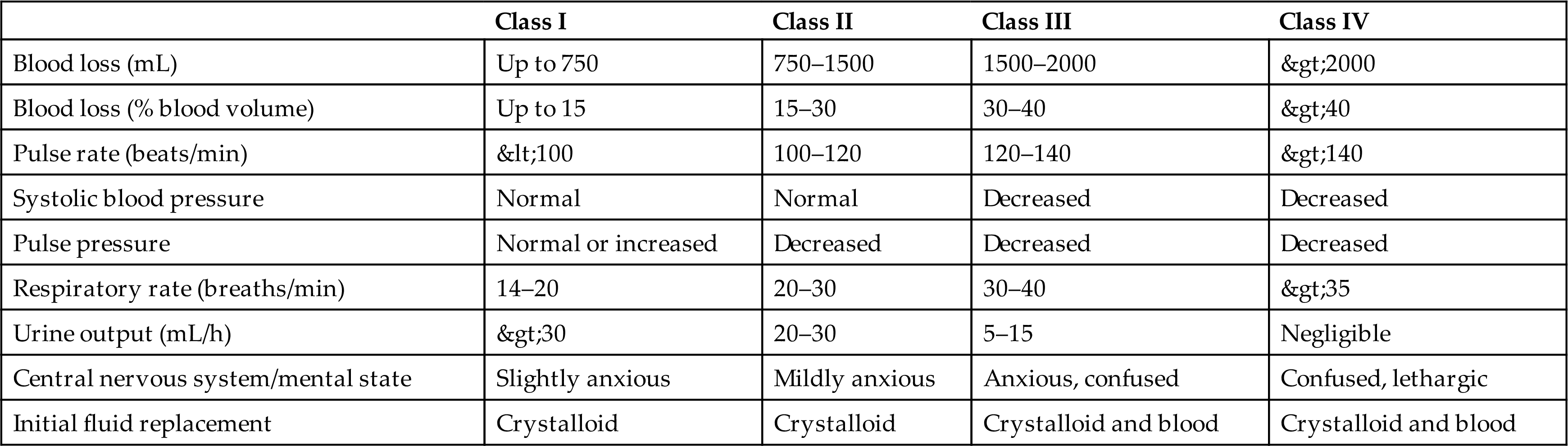

Posthemorrhagic anemia is a normocytic-normochromic anemia (see Table 29.1) caused by acute blood loss. Acute blood loss is mainly a loss of intravascular volume, and its effects depend on the rate of hemorrhage. If the blood loss is rapid, it can lead to cardiovascular collapse, shock, and death. A major cause of acute blood loss is trauma. Severe trauma is a rising global problem, resulting in an annual worldwide death rate of more than 5 million or 9% of mortalities.2,3 Uncontrolled posttraumatic bleeding is the leading cause of potentially preventable death among injured individuals. Table 29.2 presents classification of estimated blood loss for a 70 kg male based on initial presentation. The pathophysiologic mechanism of traumatic injury is an evolving field of study. Emerging is the understanding that persons with bleeding trauma are already developing complications of coagulopathy upon hospital admission. The presence of coagulopathy is related to an increased risk of multiple organ failure and death (see Emerging Science Box: Traumatic Coagulopathy).

Table 29.2

Data from Rossaint R, Bouillon B, Cerny V, et al. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: Fourth edition. Critical Care, 2016;20:100.

Within 24 hours of acute blood loss, lost plasma is replaced from the movement of water and electrolytes from tissues and interstitial spaces into the intravascular system. The hematocrit becomes lowered because of resulting hemodilution. Red blood cells are normocytic and normochromic (i.e., mean corpuscular volume [MCV] and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration [MCHC] are within normal range). A rapid elevation of circulating neutrophils occurs within a few hours due to a release of leukocytes from the bone marrow into the circulation. The platelet count can rise significantly during the early recovery from acute blood loss. Erythropoietin is stimulated from the reduction in tissue oxygenation and increases bone marrow production of erythrocytes. However, iron stores may be depleted due to loss of red blood cells from the body, and erythropoiesis may be impeded. To restore blood volume, saline, dextran, albumin, or plasma is typically used, and with large blood losses it may be necessary to transfuse fresh whole blood.

Red blood cell transfusion is an option for both acute and chronic blood loss. However, transfusion of critically ill individuals may worsen the outcome and increase morbidity and mortality. Stored red blood cells undergo structural and metabolic impairments including formation of toxic products, phosphatidylserine exposure, and shedding of microparticles. These changes promote thrombotic complications such as deep venous thrombosis (DVT) after infusion.4 In an effort to improve patient outcomes, patient blood management is a patient-centered and multidisciplinary approach to effectively manage anemia, reduce iatrogenic blood loss, and improve outcomes for those with anemia.5

Chronic Blood Loss

Anemia from chronic blood loss occurs if the loss is greater than the replacement capacity of the bone marrow. Hemorrhage that is slow and chronic produces less prominent adaptations, but an iron deficiency anemia (IDA) may develop. In adults, an otherwise unexplained IDA should be evaluated for an occult source of blood loss such as a bleeding ulcer or a malignancy.

Anemias of Diminished Erythropoiesis

There are many varied anemias of diminished red cell production that can be classified according to the underlying mechanism (Table 29.3). IDA is the most common type of anemia in the world. Other common anemias of diminished red cell production are the result of ineffective erythrocyte DNA synthesis caused by nutritional deficiencies of vitamin B12 (cobalamin) or folate (folic acid). IDA causes a microcytic anemia, whereas deficiencies of vitamin B12 and folate cause macrocytic (megaloblastic) anemias (Fig. 29.3).

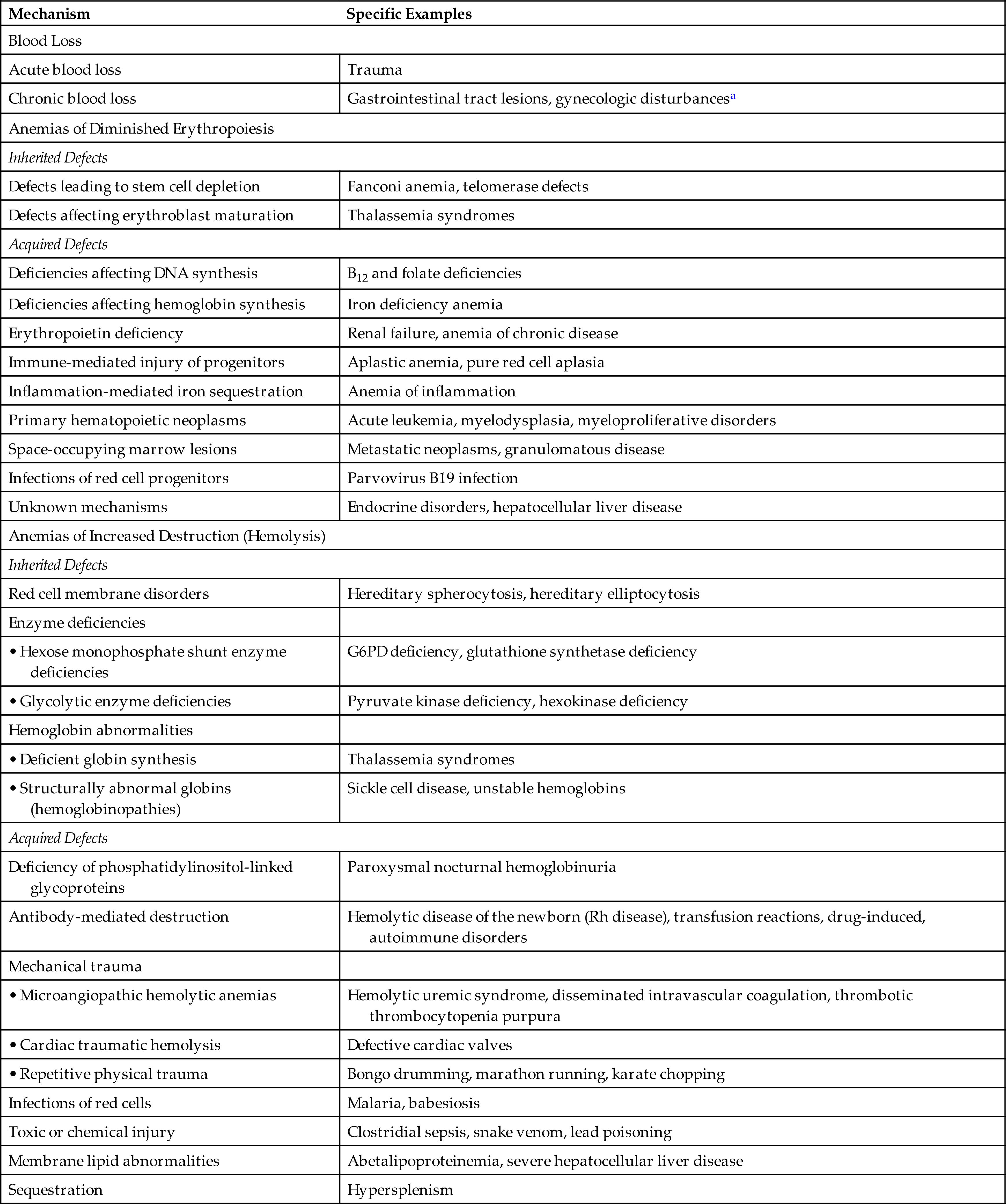

Table 29.3

| Mechanism | Specific Examples |

|---|---|

| Blood Loss | |

| Acute blood loss | Trauma |

| Chronic blood loss | Gastrointestinal tract lesions, gynecologic disturbancesa |

| Anemias of Diminished Erythropoiesis | |

| Inherited Defects | |

| Defects leading to stem cell depletion | Fanconi anemia, telomerase defects |

| Defects affecting erythroblast maturation | Thalassemia syndromes |

| Acquired Defects | |

| Deficiencies affecting DNA synthesis | B12 and folate deficiencies |

| Deficiencies affecting hemoglobin synthesis | Iron deficiency anemia |

| Erythropoietin deficiency | Renal failure, anemia of chronic disease |

| Immune-mediated injury of progenitors | Aplastic anemia, pure red cell aplasia |

| Inflammation-mediated iron sequestration | Anemia of inflammation |

| Primary hematopoietic neoplasms | Acute leukemia, myelodysplasia, myeloproliferative disorders |

| Space-occupying marrow lesions | Metastatic neoplasms, granulomatous disease |

| Infections of red cell progenitors | Parvovirus B19 infection |

| Unknown mechanisms | Endocrine disorders, hepatocellular liver disease |

| Anemias of Increased Destruction (Hemolysis) | |

| Inherited Defects | |

| Red cell membrane disorders | Hereditary spherocytosis, hereditary elliptocytosis |

| Enzyme deficiencies | |

| G6PD deficiency, glutathione synthetase deficiency | |

| Pyruvate kinase deficiency, hexokinase deficiency | |

| Hemoglobin abnormalities | |

| Thalassemia syndromes | |

| Sickle cell disease, unstable hemoglobins | |

| Acquired Defects | |

| Deficiency of phosphatidylinositol-linked glycoproteins | Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria |

| Antibody-mediated destruction | Hemolytic disease of the newborn (Rh disease), transfusion reactions, drug-induced, autoimmune disorders |

| Mechanical trauma | |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura | |

| Defective cardiac valves | |

| Bongo drumming, marathon running, karate chopping | |

| Infections of red cells | Malaria, babesiosis |

| Toxic or chemical injury | Clostridial sepsis, snake venom, lead poisoning |

| Membrane lipid abnormalities | Abetalipoproteinemia, severe hepatocellular liver disease |

| Sequestration | Hypersplenism |

G6PD, Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase.

aMost often cause of anemia is iron deficiency, not bleeding.

Data from Kumar V, Abbas A, Aster JC. Robbins & Cotran pathologic basis of disease, 10th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2021.

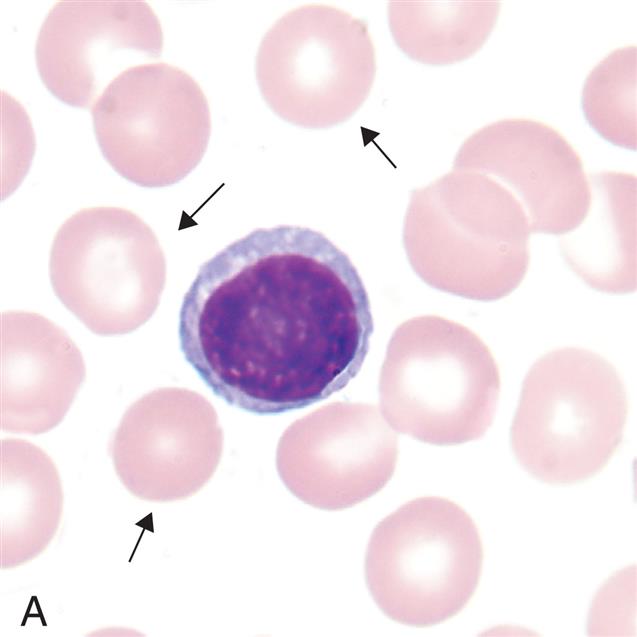

(A) Microcytes (mean cell volume [MCV] <80 fL) associated with iron deficiency anemia, thalassemia minor, chronic inflammation (some cases), lead poisoning, hemoglobinopathies (some), and sideroblastic anemia. (B) Normocytes (mean cell volume [MCV] 80–100 fL). Normal erythrocytes are approximately the same size as the nucleus of a small lymphocyte. (C) Macrocytes (mean cell volume [MCV] >100 fL). Associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency, liver disease, neonates, and reticulocytosis. (From Rodak BF, Carr JH. Clinical hematology atlas. 5th edition. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2017)

Three photomicrographs show variations in erythrocyte sizes. Top panel, A. The cell comprises hemoglobin and a layer of membrane. Middle panel, B. The cell comprises hemoglobin and a hardly visible layer of membrane. Bottom panel, C. The cell comprises hemoglobin with no membrane.

Macrocytic (Megaloblastic)—Normochromic Anemias

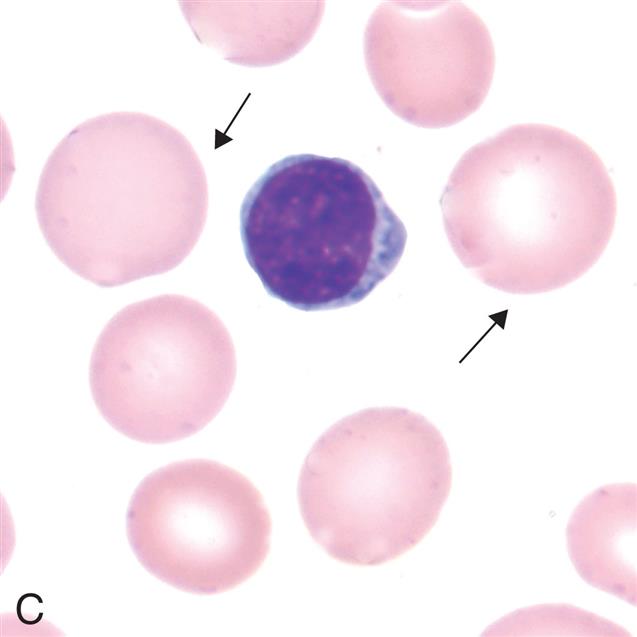

The macrocytic (megaloblastic) anemias are characterized by large stem cells (megaloblasts) in the marrow (Fig. 29.4) that mature into erythrocytes that are unusually large in size (macrocytic; elevated MCV) thickness, and volume (see Fig. 29.3C). The most common etiology for macrocytic anemias is vitamin B12 or folate deficiencies. Vitamin B12 is dependent on dietary B12 intake. Plants and vegetables contain little cobalamin and strictly vegetarian and macrobiotic diets do not provide adequate amounts. Folate is found in green leafy vegetables, fruits, nuts, eggs, and meats. Both vitamin B12 and folate levels can be affected by disorders that decrease absorption of these vitamins from the gut, and by increased demand for these nutrients in conditions such as pregnancy, hyperthyroidism, chronic infection, and disseminated cancer. Another important cause of megaloblastic anemia is medications that interfere with DNA synthesis such as chemotherapeutic drugs.

Bone marrow aspirate smear from an individual with megaloblastic red blood cell precursors and giant metamyelocytes. The chromatin in the red blood cell nuclei is more dispersed than that in normal red blood cell precursors at comparable stages of maturation; the giant metamyelocytes have dispersed nuclear chromatin in contrast to a normal metamyelocyte, which has condensed chromatin (Wright-Giemsa stain). (From Damjanov I, Linder J, eds. Anderson’s pathology, 10th edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996.)

The defective erythrocytes in megaloblastic anemias die prematurely, which decreases their numbers in the circulation, causing anemia. Premature death of damaged erythrocytes, eryptosis, is a common mechanism of cellular loss in individuals with anemia secondary to nutritional deficiencies, infections (e.g., malaria, mycoplasma), chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, renal disease), genetic diseases (e.g., beta-thalassemia, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase [G6PD] deficiency, sickle cell anemia), and myelodysplastic syndrome.6

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) synthesis and cell division are blocked or delayed in megaloblastic anemias. Defective DNA synthesis causes red cell growth and development to proceed at unequal rates. However, ribonucleic acid (RNA) replication and protein (hemoglobin) synthesis proceed normally. Asynchronous development leads to an overproduction of hemoglobin during prolonged cellular division, creating a larger than normal erythrocyte with a disproportionately small nucleus. With each cell division, the disproportion between increased RNA and cell size and decreased DNA becomes more apparent.

Pernicious anemia

Pernicious anemia (PA) is a type of megaloblastic anemia and is caused by vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency due to intestinal malabsorption. The main disorder in PA is the absence of intrinsic factor (IF) which is essential for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the ileum (see Chapter 28). Pernicious means highly injurious or destructive and reflects the fact that this condition was once fatal. It most commonly affects individuals older than age 30 who are of Northern European descent; however, it is now recognized in all populations and ethnic groups.

Deficiency of IF may be congenital. It is more often acquired as the result of an autoimmune process or conditions that damage the gastric mucosa. Congenital IF deficiency is a genetic disorder with an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Approximately 20% of individuals with PA have a family member with PA, although the pattern of transmission has not been identified.7 PA most commonly is caused by autoimmune processes directed against gastric parietal cells or IF itself. It may be a component of a cluster of autoimmune diseases affecting endocrine organs such as autoimmune thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes mellitus.8 Chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori is also implicated. Other causes include surgical removal of the stomach, resection of the ileum, and tapeworms. Environmental conditions that may contribute to the development of PA include excessive alcohol intake and smoking.

Pathophysiology

Individuals with autoimmune PA commonly have two types of antibodies: one to parietal cells and the other to IF or its binding site in the small bowel.7 IF deficiency in PA is most often associated with type A chronic atrophic (autoimmune) gastritis, whereby autoantibodies destroy parietal and zymogenic (relating to an enzyme) cells leading to gastric atrophy (see Chapter 41). H. pylori infection may cause an increase in antibody production. These autoantibodies often target gastric H+-K+ adenosine triphosphate (ATP)ase, which is the major protein constituent of parietal cell membranes. Early in progression of disease, the gastric submucosa becomes infiltrated with inflammatory cells. These cells include autoreactive T cells, which initiate gastric mucosal injury and trigger the formation of autoantibodies. Gastric mucosal injury and atrophy result in a deficiency of all secretions of the stomach—hydrochloric acid (achlorhydria), pepsin, and IF. Without adequate IF, vitamin B12 malabsorption develops. Vitamin B12 is essential for nuclear maturation and DNA synthesis in red blood cells. Deficiencies lead to an anemia characterized by abnormal RBC precursor cells in the bone marrow (megaloblasts) and enlarged mature RBCs in the circulation (macrocytes). In addition, there is an increased risk for gastric cancer in individuals with chronic gastritis and PA.

Approximately 40% to 60% of individuals with PA have autoantibodies to intrinsic factor antibodies (IFA) directly leading to vitamin B12 malabsorption in the ileum. Many of these individuals have a history of IDA and gastric achlorhydria. Individuals with unexplained IDA should be screened for autoimmune gastritis and PA.7

Clinical Manifestations

PA develops slowly (over 20 to 30 years), so by the time an individual seeks treatment, it is usually severe. Early symptoms are often ignored because they are nonspecific and vague and include infections, mood swings, and GI, cardiac, or kidney ailments.9 When the hemoglobin level has decreased to 7 to 8 g/dL, the individual experiences classic symptoms of PA: weakness, fatigue, paresthesia of feet and fingers, difficulty walking, loss of appetite, abdominal pain, weight loss, and a sore tongue that is smooth and beefy red (glossitis). The skin may become “lemon yellow” (sallow), caused by a combination of pallor and jaundice. Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly, indicating right-sided heart failure, may be present in the elderly.

Neurologic manifestations result from nerve demyelination that may produce neuronal death. The most frequently recognized deficit is a sensory neuropathy resulting in a loss of position and vibration sense that is especially prominent in the feet leading to ataxia.10 The spinal cord is affected, causing weakness and spasticity. Vision may also be impaired. Early diagnosis and treatment improve chances of recovery, and while only a small percentage experience a complete neurological recovery, most individuals experience some improvement in symptoms after treatment.11 The cerebrum also may be involved with manifestations of affective disorders, most commonly depression. Low levels of vitamin B12 have been associated with neurocognitive disorders and Alzheimer disease.

Evaluation and Treatment

Diagnosis of PA is based on clinical manifestations and test results demonstrating a macrocytic (high MCV) normochromic (normal MCHC) anemia (see Table 29.1) and low serum levels of vitamin B12. Reticulocyte counts are decreased. Confirmatory studies include bone marrow aspiration, detection of circulating antibodies against parietal cells and IF, and gastric biopsy.9

Replacement of vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is the treatment of choice. Initial injections of vitamin B12 are administered weekly until the deficiency is corrected, followed by monthly injections for the remainder of the individual's life. Conventional practice assumed that oral preparations were ineffective because the lack of IF meant there would be continued malabsorption of vitamin B12. However, high doses of orally administered vitamin B12 can be absorbed across the small bowel in many individuals and can be considered as an alternative treatment for PA.7 The effectiveness of B12 replacement therapy is determined by a rising reticulocyte count. Blood counts return to normal within 5 to 6 weeks. PA cannot be cured, so maintenance therapy is lifelong. Treated individuals should be monitored for the development of gastric cancer and IDA.

Folate deficiency anemia

A deficiency of folic acid results in a megaloblastic anemia having the same pathologic consequences as those caused by vitamin B12 deficiency. Folate (folic acid) is an essential vitamin required for RNA and DNA synthesis within the maturing erythrocyte. Humans are totally dependent on dietary intake of folate to meet the daily requirement of 50 to 200 mg/day. It is estimated that at least 10% of North Americans are folate deficient, but the incidence has been decreasing in the United States since the fortification of foods with folate and the increased use of folate supplements. Increased amounts are required for lactating and pregnant females, and deficiencies of folate can cause neural tube defects in the developing fetus. Folate deficiency occurs more often than B12 deficiency, particularly in alcoholics and individuals with chronic malnourishment. Inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis) may be the underlying cause of folate malabsorption in some individuals, and treatment with sulfasalazine decreases folate absorption from the gut.

Folate is absorbed from the upper small intestine and does not require any other element (e.g., IF) to facilitate absorption. After absorption, folate circulates through the liver, where it is stored. Folates are coenzymes required for the synthesis of thymine and purines (adenine and guanine) and the conversion of homocysteine to methionine.12 Deficient production of thymine affects cells undergoing rapid division (e.g., bone marrow cells undergoing erythropoiesis) resulting in megaloblastic precursor cells and a macrocytic anemia.

Clinical manifestations are similar to those apparent in individuals with PA. Specific manifestations include cheilosis (scales and fissures of the mouth), stomatitis (inflammation of the mouth), and painful ulcerations of the buccal mucosa and tongue characteristic of burning mouth syndrome. Burning mouth syndrome also may be secondary to other disorders (e.g., extremely dry mouth, infection, autoimmune disease, nutritional deficiencies, and other conditions) and is not diagnostic for folate deficiency. Dysphagia, flatulence, and watery diarrhea may be present, as well as histologic changes in the GI tract similar to those seen in celiac disease (see Chapter 42). Neurologic manifestations, if present, may be caused by thiamine deficiency, which often accompanies folate deficiency in malnourished individuals.

Evaluation of folate deficiency is based on clinical manifestations, the appearance of macrocytic RBCs (high MCV) in the blood, and the measurement of serum folate levels. Treatment requires administration of oral folate preparations until adequate blood levels are obtained and manifestations are reduced or eliminated. Long-term therapy is not necessary if the appropriate dietary adjustments are made to maintain adequate intake. Manifestations of anemia disappear within 1 to 2 weeks after administration of folate.

Megaloblastic anemia caused by medications

Many drugs can directly affect DNA synthesis and thereby interfere with RBC maturation leading to megaloblastic anemia.12 These drugs include immunomodulatory drugs (e.g., azathioprine and leflunomide), chemotherapeutics (e.g., fluorouracil and methotrexate), allopurinol, and trimethoprim (sulfa drug).12 Other medications reduce vitamin B12 or folate absorption. Management includes discontinuation of the drug if possible, or if not, vitamin supplementation is indicated.

Microcytic-Hypochromic Anemias

The microcytic-hypochromic anemias are characterized by abnormally small erythrocytes (low MCV) (see Figs. 29.1 and 29.3A) that contain reduced amounts of hemoglobin (low MCHC). Sideroblastic anemia can cause erythrocytes to be microcytic and hypochromic, (see Table 29.1), but IDA is far more common.

Iron deficiency anemia

IDA is the most common nutritional disorder worldwide, affecting 10% to 20% of the world’s population, occurring in both developed and developing countries.13 The causes of IDA include (1) dietary deficiency, (2) impaired absorption (e.g., celiac disease, disorders of fat absorption), (3) increased requirement, (4) chronic blood loss, and (5) chronic diarrhea.

IDA is common in the United States, particularly in toddlers, adolescent girls, and women of childbearing age. Other populations at risk for IDA include those living in poverty, infants consuming cow’s milk (decreased bioavailability of iron), older individuals ingesting restricted diets, and teenagers with poor diets (junk food). An increased prevalence of iron deficiency has been observed in those with eating disorders, as well as in overweight children, adolescents, and women.13 Premenopausal women have an increased iron requirement, especially during pregnancy and with excessive menstrual bleeding. Increased requirement also is a major cause of iron deficiency in growing infants, children, and adolescents. Other causes of IDA include bariatric surgery and surgical procedures that decrease stomach acidity.

Both sexes may have IDA secondary to bleeding as a result of gastric or duodenal ulcers, hiatal hernia, esophageal varices, cirrhosis, hemorrhoids, inflammatory bowel disease, or cancer. In fact, unexplained IDA in a male or a postmenopausal woman may be the first indication of GI disease.

Children in developing countries often are affected by chronic parasite infestations that result in blood and iron loss that is greater than dietary intake, thus causing IDA. Treatment of helminth infections improves the anemia as well as appetite and growth. H. pylori infection impairs iron uptake and is a cause of iron-refractory or iron-dependent anemia of previously unknown origin in adults. Children in resource-poor conditions often are exposed to unsafe levels of toxins such as lead (see Chapter 2). Chronic lead poisoning can produce a mild microcytic anemia, and the absorption of lead can prevent the normal addition of iron to heme molecules resulting in IDA.14 Furthermore, IDA is associated with pica, which can lead to ingestion of lead-containing paint and soil. IDA and lead poisoning can act synergistically to cause anemia more severe than would either condition alone. Treatment for iron deficiency is associated with a decrease in lead levels.

Pathophysiology

IDA is a hypochromic-microcytic anemia (see Fig. 29.3A) and occurs when iron stores are depleted. Inadequate dietary intake and excessive blood loss deplete iron stores and reduce hemoglobin synthesis. When total body stores of iron are low, iron deprivation for erythroblasts and other tissues occurs. In some cases, iron stores may be sufficient, but delivery is inadequate to maintain heme synthesis, thus producing a functional or relative iron deficiency. For example, inflammation can cause withholding of iron from the plasma, particularly through the action of the peptide hepcidin, the main regulator of systemic iron balance (see Chapter 28).15 Hepcidin inhibits iron transfer to the plasma by binding to ferroportin, causing it to be endocytosed and degraded.16

Iron in the form of hemoglobin is in constant demand by the body. Iron is recyclable; therefore, the body maintains a balance between iron that is contained in hemoglobin and iron that is in storage and available for future hemoglobin synthesis (see Chapter 28). Blood loss disrupts this balance by creating a need for more iron, thus depleting the iron stores more rapidly to replace the iron that is lost from the body due to bleeding.

Iron contributes to immune function by regulating several immune mechanisms. Acquired hypoferremia (deficiency of iron in the blood) due to a decrease in hepcidin may be part of the body's response to infection.17 Many pathogens require iron for survival; thus, hypoferremia would hamper their growth. In contrast, neutrophils and macrophages require adequate iron to function appropriately in the innate immune response to infection. The precise benefits or detriments of iron deficiency and immunity remain under investigation.

IDA occurs when the demand for iron exceeds the supply and develops slowly through three overlapping stages. Stage I is characterized by decreased bone marrow iron stores; hemoglobin and serum iron remain normal. In stage II, iron transportation to bone marrow is diminished, resulting in iron-deficient erythropoiesis. Stage III begins when the small hemoglobin-deficient cells enter the circulation to replace the normal aged erythrocytes that have been removed from the circulation. The manifestations of IDA appear in stage III, when there is depletion of iron stores and diminished hemoglobin production.

Clinical Manifestations

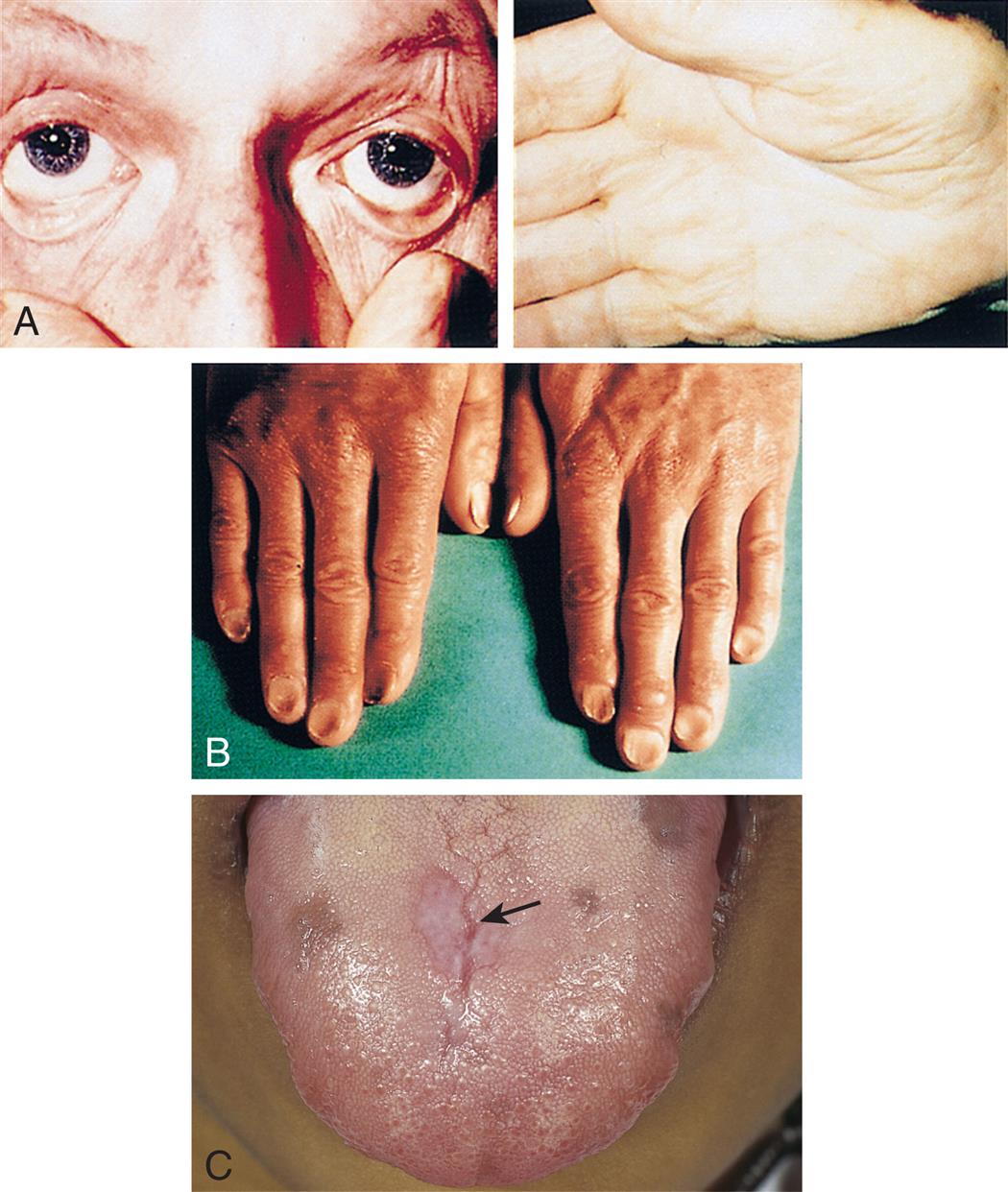

Symptoms of IDA begin gradually, and individuals may not seek medical attention until hemoglobin levels have decreased to about 7 to 8 g/dL. Nonspecific early symptoms include fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, and pale earlobes, palms, and conjunctivae (Fig. 29.5A). As the condition progresses and becomes more severe, structural and functional changes occur in epithelial tissue. Koilonychia or spoon-shaped fingernails become brittle, thin, and coarsely ridged as a result of impaired capillary circulation (see Fig. 29.5B). Other manifestations include cheilosis (scales and fissures of the mouth), stomatitis (inflammation of the mouth), and painful ulcerations of the buccal mucosa and tongue characteristic of burning (glossitis) (see Fig. 29.5C). Difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia) is associated with an esophageal web, a thin, concentric extension of normal esophageal tissue consisting of mucosa and submucosa at the juncture between the hypopharynx and esophagus. Dysphagia is worsened by hyposalivation. Individuals with IDA also exhibit gastritis, neuromuscular changes, headache, irritability, tingling, numbness, and vasomotor disturbances. Alterations in gait are rare. Iron deficiency in children is associated with numerous adverse manifestations, especially cognitive impairment. Cognitive impairment may be long-lasting and irreversible (see Chapter 30).

(A) Pallor and iron deficiency. Pallor of the skin, mucous membranes, and palmar creases in an individual with a hemoglobin level of 9 g/dL. Palmar creases become as pale as the surrounding skin when the hemoglobin level approaches 7 g/dL. (B) Koilonychia. The nails are concave, ridged, and brittle. (C) Glossitis. Tongue of individual with iron deficiency anemia has bald, fissured appearance caused by loss of papillae and flattening. (From Hoffbrand AV, Pettit JE, Vyas P. Color atlas of clinical hematology, 4th edition. London: Mosby; 2009; B, Courtesy Dr. S.M. Knowles.)

Four closeups show manifestations of iron deficiency anemia. Top panel, A. The closeup on the left shows creased eyes. The closeup on the right shows creased palms. Middle panel, B. The closeup shows the nails with concave dents at the center and elevated edges. Bottom panel, C. The closeup shows fissures on a person’s tongue.

Evaluation and Treatment

Initial evaluation is based on symptoms and decreased levels of hemoglobin and hematocrit and the finding of microcytic (low MCV) and hypochromic (low MCHC) erythrocytes in the blood. Decreased serum iron, ferritin, and transferrin saturation levels are also found. A sensitive indicator of heme synthesis is the amount of free erythrocyte protoporphyrin (FEP) within erythrocytes.

An initial step in treatment of IDA is to identify and eliminate sources of blood loss. Oral iron replacement therapy is indicated, and hematocrit levels should improve within 1 to 2 months of therapy. Parenteral iron replacement is used in instances of uncontrolled chronic blood loss, intolerance to oral iron replacement, intestinal malabsorption, or poor adherence to oral therapy. Serum ferritin level is a more precise measurement of improvement. A rapid decrease in fatigue, lethargy, and other associated symptoms is generally seen within the first month of therapy. Replacement therapy may continue for many months. Menstruating females may need daily oral iron replacement therapy until menopause.

Normocytic-Normochromic Anemia

Some causes of anemia do not change the size, color, or shape of erythrocytes (see Figs. 29.1 and 29.3B). Two important causes of normocytic-normochromic anemia are AI and aplastic anemia (AA).

Anemia of inflammation

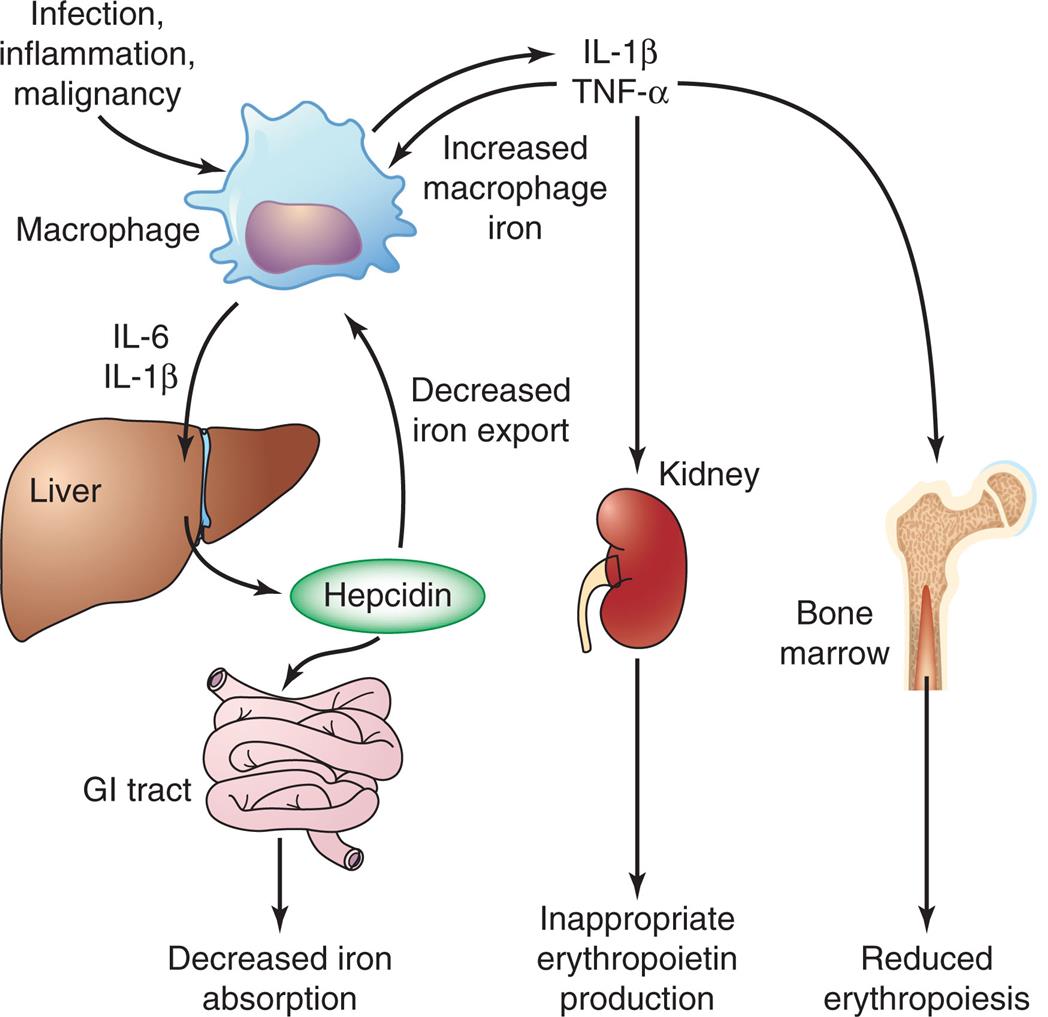

Anemia of inflammation (AI) (also called anemia of chronic inflammation and anemia of chronic disease [ACD]), is a mild to moderate anemia resulting from decreased erythropoiesis and impaired iron utilization in individuals with chronic diseases that produce systemic inflammation (e.g., infections, cancer, and chronic inflammatory or autoimmune diseases). It is one of the most common conditions encountered in medicine. Table 29.4 lists some of these causes of AI. AI is a common type of anemia in hospitalized individuals where it is observed in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and congestive heart failure (CHF); in persons with critical illnesses after acute events such as major surgery, severe trauma, myocardial infarction, and sepsis; and in the elderly. The elderly may be predisposed to AI related to age-associated hematopoietic changes with increased concentrations of inflammatory cytokines. More than 50% of elderly individuals who reside in nursing homes have anemia, with two-thirds of cases being AI or unexplained. The elderly with characteristics of AI without an underlying malignancy or inflammatory condition are described as having primary defective iron utilization syndrome.

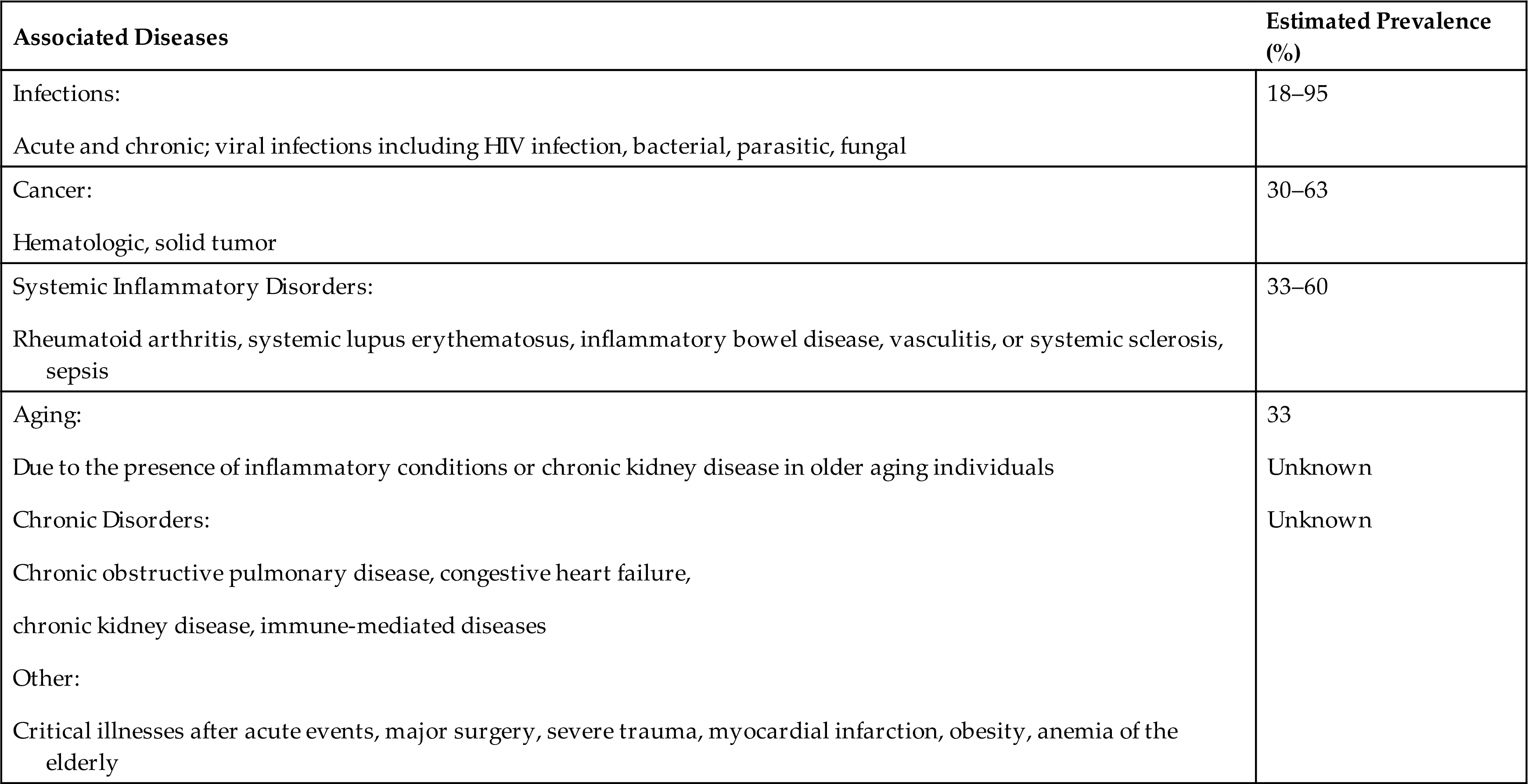

Table 29.4

Data from Weiss G, Schett G. Anaemia in inflammatory rhematic diseases. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 2013;9(4):205–215; Weiss G, Ganz T, Goodnough LT. Anemia of inflammation. Blood, 2016;133(1):40–50; Nemeth E, Ganz T. Anemia of inflammation. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 2014;28(4):671–681. Fraenkel PG. Anemia of inflammation: a review. The Medical Clinics of North America. 2017;101(2):285−296; Weiss G, Ganz T, Goodnough LT. Anemia of inflammation. Blood. 2019 Jan 3;133(1):40-50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-06-856500. Epub 2018 Nov 6. PMID: 30401705; PMCID: PMC6536698.

Pathophysiology

AI usually develops after 1 to 2 months of disease activity. The initial severity is related to the underlying disorder, but, although persistent, it usually does not progress. AI results from a combination of (1) decreased erythrocyte life span, (2) suppressed production of erythropoietin, (3) ineffective bone marrow response to erythropoietin, and (4) altered iron metabolism and iron dynamics in macrophages. During chronic inflammation, a large variety of cytokines are released by lymphocytes, macrophages, and the affected tissue. Inflammatory cytokines increase hepcidin levels, which reduces iron absorption, sequesters iron in macrophages, and suppresses erythropoietin production (Fig. 29.6).16 Impaired iron metabolism is partially the result of iron sequestration (Emerging Science Box: Regulation of Iron Metabolism). Normal iron transport by transferrin also may be decreased as a result of inflammation-related increases in the levels of circulating lactoferrin and apoferritin.

GI, Gastrointestinal; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

An illustrated flowchart shows the mechanism for the anemia of inflammation. • T N F-alpha triggers the bone marrow in producing reduced erythropoiesis. • T N F-alpha triggers the kidney in producing inappropriate erythropoietin. • T N F-alpha produces increased macrophage iron. • Infection, inflammation, and malignancy macrophage produces I L-1 beta. • I L-6 and I L-1 beta from macrophage triggers the liver in producing hepcidin. • Hepcidin decreases iron export to the macrophage. • Hepcidin triggers the G I tract in decreasing iron absorption.

The erythropoietic defect in AI is failure to increase erythropoiesis in response to decreased numbers of erythrocytes. In part, decreased erythropoiesis results from diminished production of erythropoietin by the kidneys. In addition, the failure in erythropoiesis may reflect decreased responsiveness of erythroid progenitors to erythropoietin. Decreased availability of iron would diminish the rate of erythropoiesis. Proliferation of erythroid cells also is inhibited by proinflammatory cytokines. Loss of integrins may prevent adequate interaction with stromal cells and matrix proteins and inhibit erythropoiesis.

Erythrocyte destruction is the result of eryptosis (described earlier in this chapter). Most of the diseases responsible for AI cause damage to erythrocytes resulting in macrophage activity. Platelet function also may be defective in these individuals, which results in chronic bleeding and loss of erythrocytes.

Clinical Manifestations

AI is usually in the mild to moderate range. Individuals may be asymptomatic, or the anemia may be a chance clinical finding. If there is a significant drop in hemoglobin levels, clinical manifestations of anemia appear.

Evaluation and Treatment

Initially, AI is normocytic-normochromic, but with persistence it becomes hypochromic and microcytic (see Table 29.1). AI is characterized by low levels of circulating iron and reduced levels of transferrin. The most significant finding of AI is very high total body iron storage, although inadequate iron is released from the bone marrow for erythropoiesis. A first indication of AI is often a failure to respond to conventional iron replacement therapy. Levels of erythropoietin are generally lower than expected for the degree of anemia. Individuals frequently present with low or normal total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), normal or high serum ferritin levels, and low concentrations of soluble transferrin receptor. It occasionally may be difficult to differentiate AI from IDA.

Use of erythropoietin in treatment of AI associated with arthritis, malignancies, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) has met with limited success. Individuals with severe anemia secondary to chronic kidney disease (CKD) can be treated successfully with erythropoietin and treatments to increase iron stores. However, the optimal degree of restoration of hemoglobin levels has not been determined; a return to normal levels increases the risk of hypertension, stroke, and death.18 The principal treatment is easement of the underlying disorder. Individuals with AI, but without evidence of inflammatory or infectious conditions, should be screened for malignancies.

Aplastic anemia

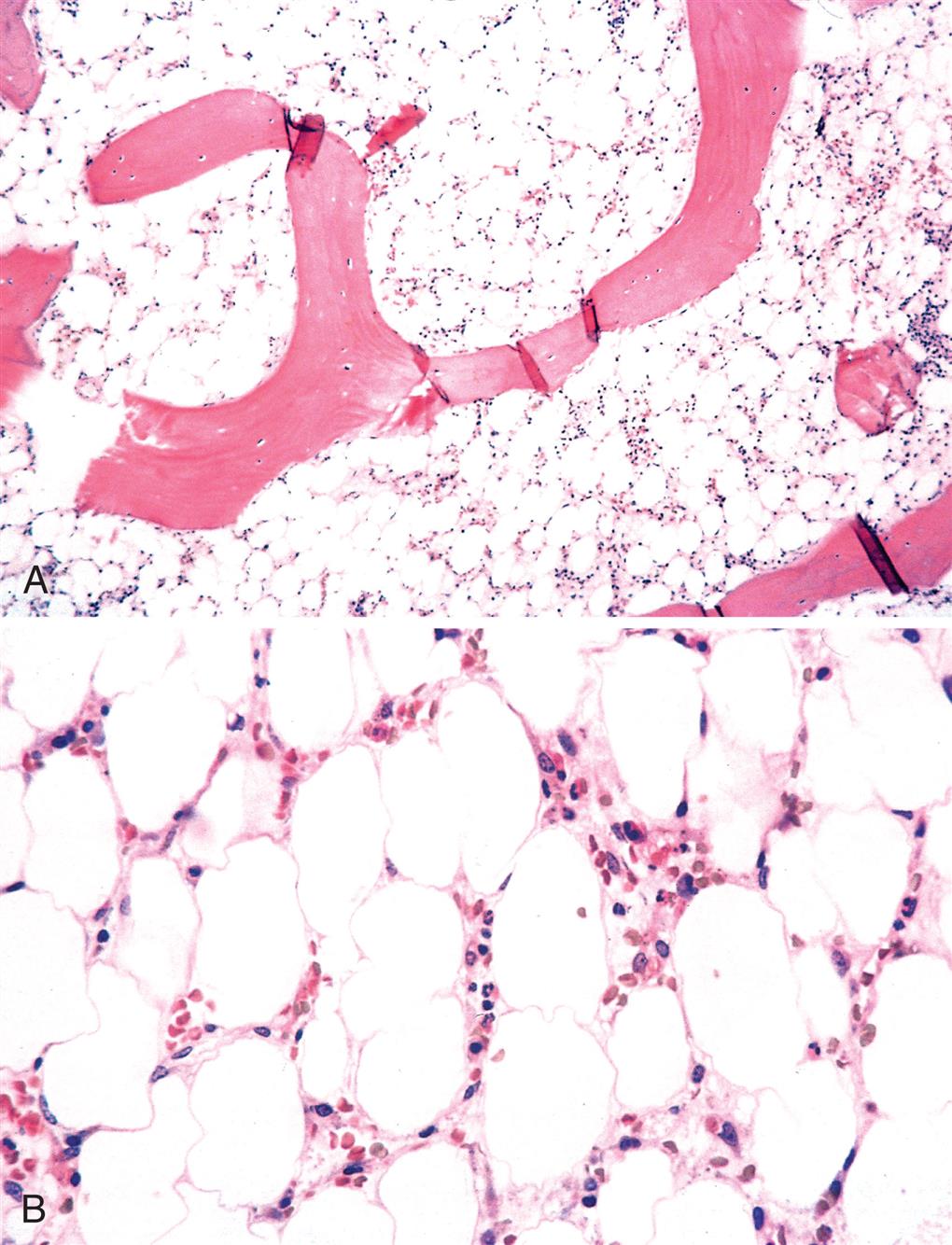

Aplastic anemia (AA) is a hematopoietic failure of the bone marrow leading to a reduction in the effective production of mature blood cells and resulting in peripheral pancytopenia (anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia), which is a reduction or absence of all three blood cell types. (Fig. 29.7) The incidence of AA in the United States is low; however, the incidence in developing countries is higher related to greater exposure to certain chemicals known to cause AA. The incidence is bimodal, with one peak occurring between 15 and 25 years of age and a second peak occurring in individuals older than age 60. AA is equally distributed between genders.

The common pathology of the bone marrow replaced by fat can result from chemical or physical damage (iatrogenic; benzene); immune destruction (mainly T cells); and as a constitutional defect in genes important in maintenance of cell integrity and immune regulation. (A) Low power. (B) High power. (From Kumar V, Abbas A, Aster J. Robbins & Cotran pathologic basis of disease, 10th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2021.)

Idiopathic AA (primary acquired; autoimmune) accounts for approximately 75% of all confirmed cases. Secondary AA, which accounts for approximately 15% of cases, is caused by a variety of known chemical agents and ionizing radiation (Box 29.1). Total body irradiation is a well-described cause of AA and in certain instances may be used therapeutically for this effect in the treatment of certain cancers or for organ and bone marrow transplantation (BMT). Infections also are known to cause AA, with viruses being the most common agent, including the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and hepatitis (non-A, non-B, non-C, and non-G forms of the virus). Persistent parvovirus B19 infection also has been identified as producing bone marrow failure resulting in AA.

Another condition associated with AA is pure red cell aplasia (PRCA), in which only the erythrocytes are affected. PRCA is a rare disorder and has been associated with autoimmune, viral, and neoplastic (leukemias) disorders; infiltrative disorders of the bone marrow (myelofibrosis); renal failure; hepatitis; mononucleosis; and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). It also is a well-recognized but infrequent complication of allogeneic BMT, particularly when there is donor-recipient ABO mismatch. A thymoma often is found in association with PRCA and is also present in Diamond-Blackfan syndrome, a congenital disorder.

AA is associated with one or more somatic mutations. A subset of these is found to have defective telomerase RNA, resulting in shortened telomere.19 A very small percentage of AA cases are linked to inherited genetic alterations. Fanconi anemia is a rare genetic anemia characterized by pancytopenia resulting from defects in DNA repair. This anemia develops early in life and is accompanied by multiple congenital anomalies.

Pathophysiology

The characteristic lesion of AA is a hypocellular bone marrow that has been replaced with fat. Although the pathogenesis is not fully defined, AA results from loss of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) or their progenitors at various stages of differentiation. Two etiologies and mechanisms are observed: an immune-mediated destruction of bone marrow progenitor cells (idiopathic AA) and an intrinsic abnormality of stem cells (secondary AA).

Several immune abnormalities are found in individuals with idiopathic AA including dysregulated CD4 +, CD8 +, natural killer, and Th-17 T-cell responses and reduced numbers of regulatory T cells.20 Elevations of circulating levels of inflammatory or myelosuppressive cytokines, such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) are seen. The initial immune response may be triggered by pathogens, drugs, or chemicals, or by neoantigens through epigenetic mechanisms. It also is interesting that transient and persistent bone marrow hypoplasia has been linked to many microorganisms, and the interaction between the gut microbiota and immune system is hypothesized as an initial insult in the development of bone marrow failure syndromes such as AA.21

In secondary AA, stem cells and the bone marrow microenvironment may be altered from exposure to drugs, infectious agents, or other environmental factors.20 Somatic changes in stem cell chromosomes may trigger these autoimmune processes and may contribute to the development of myelodysplastic syndrome and leukemia in individuals with AA.19,20

Clinical Manifestations

The onset of symptoms in AA is related to the rapidity with which the bone marrow is destroyed and replaced. Approximately 50% of AA cases progress rapidly, with a high risk of death from overwhelming infection or bleeding. In some cases, the rate of decline is slow, and the individual may adapt progressively to a new level of hematologic function. This condition is referred to as hypoplastic anemia rather than AA.

Initial symptoms depend on which cell line is affected. Rapidly progressing disease is usually associated with hypoxemia, pallor, and weakness. Other symptoms include fever and dyspnea and rapidly developing signs of hemorrhaging if platelets are affected (e.g., unexplained bruising, nosebleeds, bleeding gums, bleeding in the GI tract, prolonged bleeding at sites of minor injury). A more insidious onset over weeks or months is characterized by progressive weakness and fatigue with gradually developing signs of hemorrhaging. Major hemorrhage may occur from any organ at any time; however, it is generally observed in the late stages and is often secondary to other events. In both rapid onset and slow onset AA, diminished leukocyte production may result in a progressive frequency and prolongation of infections. Ulcerations of the mouth and pharynx or a low-grade cellulitis in the neck may be seen. Neurologic changes may become evident when hemorrhages have occurred within the system.

Evaluation and Treatment

AA is suspected if levels of circulating erythrocytes, leukocytes, and platelets are diminished. The diagnosis is confirmed by bone marrow biopsy. The bone marrow usually has reduced cellularity (e.g., less than 25% normal cellularity). The morphology of the few remaining hematopoietic cells is usually normal. Occasionally the erythrocytes are macrocytic, with anisocytosis and poikilocytosis, and may appear immature.

Bone marrow and, most recently, peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (SCT) from a histocompatible sibling often cures the underlying bone marrow failure. Before transplantation, the recipient usually receives radiation or chemotherapy to deplete the bone marrow of disease-causing precursor cells. Infection and graft-versus-host (GVH) disease are major contributors to premature death after transplantation.22

For those individuals unable to undergo BMT or who lack a suitable sibling donor, immunosuppression remains the treatment of choice. Drugs like antithymocyte globulin (ATG) and cyclosporine suppress the activity of autoimmune cells. Corticosteroids are often used concurrently with ATG and cyclosporine. The addition of recombinant hematopoietic growth factors (e.g., granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor [GM-CSF], IL-6, and epoetin) to immunosuppressive therapy can produce significant additional benefit in both children and adults. A promising new treatment for AA is the oral thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor agonist eltrombopag which improves HSC maintenance and expansion.23

Anemias of Increased Destruction

Hemolytic anemia is premature accelerated destruction of erythrocytes, either episodically or continuously. They can be inherited or acquired (see Fig. 29.1). Hemolytic anemias may develop due to destruction outside of blood vessels or intravascularly. Extravascular hemolysis is the destruction of erythrocytes by macrophages which are abundant in the spleen, bone marrow, and liver. Macrophages will phagocytose erythrocytes that have been opsonized by antibodies, erythrocytes with structural alterations of the membrane surface, or erythrocytes that have become more rigid due to intracellular defects. Intravascular hemolysis most often is caused by antibody-mediated complement fixation. It can also be caused by mechanical injury, intracellular parasites, or exogenous toxic factors (e.g., clostridial sepsis, snake venom, lead poisoning). Although compensatory erythropoiesis provides new erythrocytes to replace those that are lost, if destruction outpaces production, then anemia develops. Hemolytic anemias may be either congenital or acquired.

Congenital hemolytic anemias result from intrinsic defects in erythrocytes, including the red cell membrane (e.g., hereditary spherocytosis, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria), enzymatic pathways (e.g., glucose6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency), and hemoglobin synthesis (e.g., the thalassemia syndromes, sickle cell anemia) (see Chapter 30).

Acquired hemolytic anemias are usually immunologic, such as erythrocyte destruction caused by autoantibodies against erythrocyte antigens (e.g., autoimmune hemolytic anemia), isohemagglutinins (e.g., mismatched erythrocyte transfusions), or allergic reactions against drug antigens adsorbed onto the erythrocyte surface (drug-induced hemolytic anemia). Isohemagglutinins, erythrocyte antigens, autoantibodies, and allergic reactions are discussed in Chapter 9.

Pathophysiology

Autoimmune hemolytic anemias (AIHAs) are acquired disorders caused by autoantibodies, complement, or both, directed against antigens on the surface of erythrocytes. Aging, genetic background, autoimmune disorders, infections, medications, cancers (especially lymphomas), and organ transplants are risk factors for AIHA development. Recent studies implicate T- and B-cell dysregulation, reduced T regulatory cell function, and impaired lymphocyte apoptosis.24 Five types of AIHAs have been described: (1) warm reactive antibody type, (2) cold agglutinin type, (3) cold hemolysin type (paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria), (4) alloimmune hemolytic anemia, and (5) drug-induced hemolytic anemia. This classification is based on the optimal temperature at which the antibody binds to erythrocytes and the mechanism of erythrocyte destruction.

Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia is the most common form of AIHA accounting for about 1/3 of cases.24 Approximately half of the cases are associated with other diseases, especially lymphomas but also chronic lymphocytic leukemia, other neoplastic disorders, or SLE. The anemia is caused by immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies that bind to erythrocytes at normal body temperature. The most common targets of these antibodies are Rh antigens on the erythrocyte surface.25 The IgG-coated erythrocytes bind to the Fc receptors on monocytes and splenic macrophages and are removed by phagocytosis (see Chapter 9).

Cold agglutinin autoimmune hemolytic anemia is mediated by immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies and occurs less often than warm antibody hemolysis. These antibodies optimally bind to erythrocytes at colder temperatures (lower than 31°C [87.8°F]). Cold agglutinin autoantibodies may appear acutely during recovery from certain infectious disorders, particularly infectious mononucleosis (IM), Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and disseminated tuberculosis (TB). Chronic cold agglutinin AIHAs also can occur in association with lymphoid neoplasm and other unknown or idiopathic conditions. IgM autoantibodies are directed against erythrocyte carbohydrate antigens on the surface of erythrocytes.25 In the colder areas of the body (e.g., fingers, toes, nose, ears, exposed skin), particularly during cold weather, the IgM autoantibodies bind to circulating erythrocytes where they activate complement leading to phagocytosis by mononuclear phagocytes in the liver and spleen (see Chapter 9). The IgM is rapidly released when the blood recirculates and warms. The severity of hemolysis is variable and may result in a progressive chronic anemia. Prolonged exposure to the cold may lead to gangrene.

Cold hemolysin autoimmune hemolytic anemia (paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria) is a disorder in which exposure to cold initiates acute intravascular hemolysis that, unlike cold agglutinin anemia, is severe enough to cause hemoglobinuria. The acute form occurs primarily in children younger than the age of 10 years and is usually preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection or flulike symptoms. Viral infections with measles, mumps, or varicella, as well as M. pneumoniae infections, have also been linked to an onset of paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria. The anemia may be rapidly progressing and associated with fever, reddish brown urine, hemoglobinuria, jaundice, abdominal pains, and pallor, with about 25% of individuals presenting with hepatomegaly and splenomegaly.

A transfusion reaction is an example of alloimmune hemolytic anemia (see Chapter 9). Transfused blood that is mismatched for ABO antigens is destroyed by preexisting isohemagglutinins in the recipient. Isohemagglutinins, which are generally IgM antibodies, activate complement, resulting in a rapid intravascular hemolysis. The individual may immediately experience fever, chills, dyspnea, and hypotension and may progress to shock.

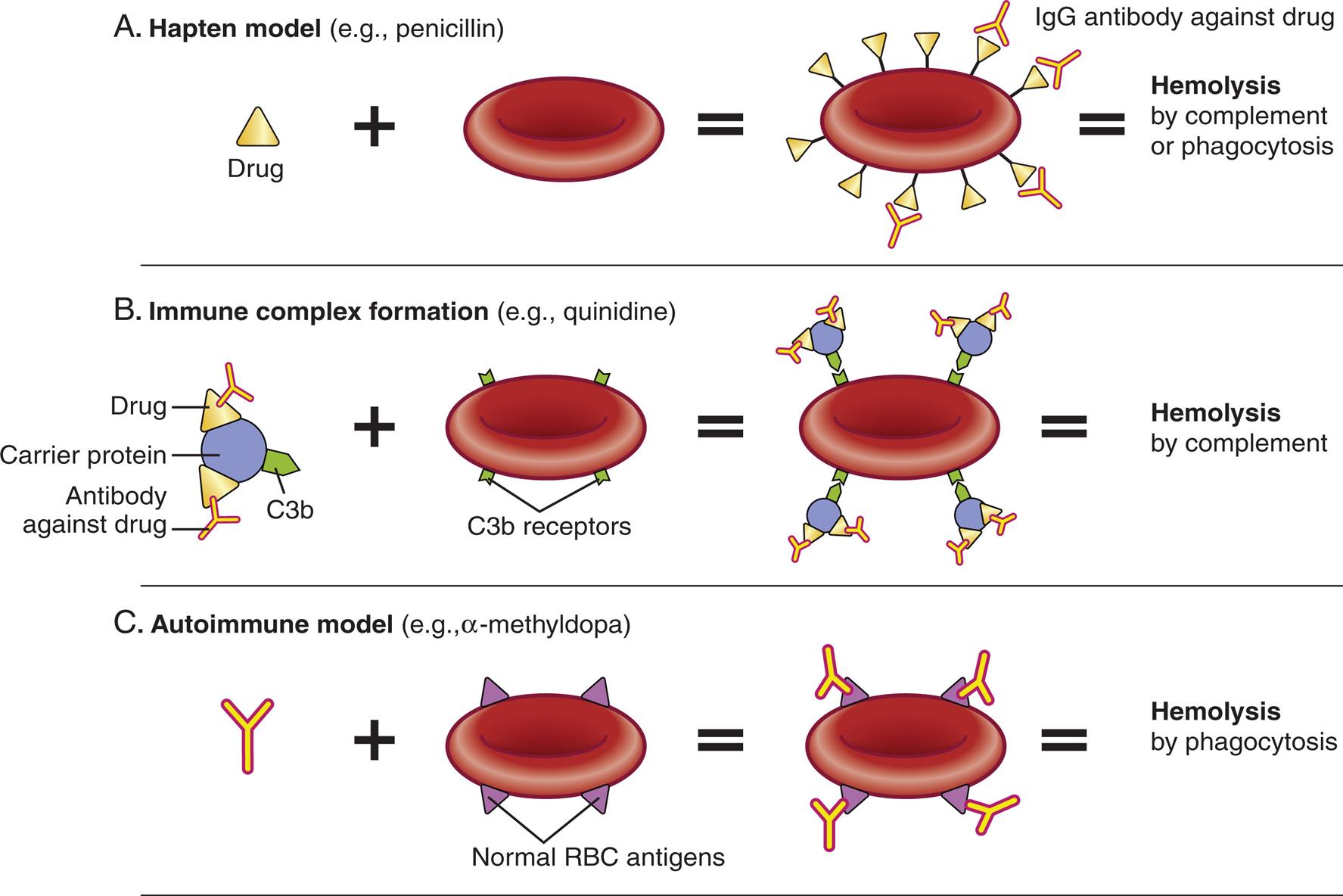

Drug-induced hemolytic anemia is a form of immune hemolytic anemia usually resulting from an allergic reaction against foreign antigens (e.g., antibiotics) (see Chapter 9). A low molecular weight drug may function as a hapten and bind to proteins on the surface of erythrocytes. IgG antibody is directed against the drug or against the unique antigen formed by the binding of the drug and erythrocyte protein (Fig. 29.8A). This leads to opsonization of the erythrocyte and phagocytosis by macrophages in the liver. Autoimmunity also can occur due to the formation of immune complexes which attach to erythrocytes and activate complement (see Fig. 29.8B). This mechanism also may explain some of the anemia observed in other immune complex conditions, such as SLE. Rarely, a drug (e.g., methyldopa) initiates the formation of cross-reactive antibodies that bind with erythrocyte antigens leading to phagocytosis by macrophages (see Fig. 29.8C).

Three illustrations show models of drug induced hemolytic anemia. Top panel, A. Hapten model (example, penicillin). The illustration shows: drug plus red blood cell bound with I g G antibody against drug equals hemolysis by complement or phagocytosis. Middle panel, B. Immune complex formation (example, quinidine). The illustration shows: carrier protein (has C 3 b component) with drug and antibody against drug plus blood cell with C 3 b receptors equals blood cell with C 3 b receptors attracting carrier proteins equals hemolysis by complement. Bottom panel, C. Autoimmune model (example, alpha-methyldopa). I g G antibody plus blood cell with normal R B C antigens equals blood cell with normal R B C antigens attracting I g G antibody equals hemolysis by phagocytosis.

Clinical Manifestations

The presence and severity of signs and symptoms of hemolytic anemia depend on the degree of anemia and hemolysis and the success of compensatory erythropoiesis.24 Bone marrow is capable of increasing red cell production up to eight times its normal rate. When accelerated erythrocyte production is incapable of keeping up with destruction, anemia develops. The severity of anemia varies widely among individuals, even in those who have the same underlying illness. Severe disease may be diagnosed shortly after birth or within the first year of life. Mild to moderate anemia is more common because the shortened erythrocyte survival time is offset by increased erythropoiesis. Some individuals have no symptoms of anemia, and the underlying hemolytic process remains undetected unless some other complications develop during the course of the disease. Acute conditions that disrupt the delicate equilibrium of accelerated erythropoiesis and erythrocyte destruction may precipitate a crisis. The most common type of crisis is aplastic and results from failure of bone marrow erythrocyte production.

Jaundice (icterus) is present when heme release from destroyed erythrocytes exceeds the liver’s ability to conjugate and excrete bilirubin (see Chapter 41). Adults with mild or moderate hemolytic anemia may not have icterus, or it may be visible only in the sclera, and thus remains unnoticed. Cardiovascular and respiratory manifestations vary with the degree of anemia. Thromboembolism may occur, and pulmonary embolism is a common finding during autopsies of individuals with immune hemolytic anemia.25 Individuals with congenital hemolytic disorders demonstrate splenomegaly, and in some cases, the spleen may become quite enlarged. Children who have hemolytic anemia may develop skeletal abnormalities caused by expansion of erythroid bone marrow during the active phase of growth and development.

Evaluation and Treatment

Diagnosis of AIHA is based on clinical manifestations and blood tests. A normocytic- normochromic anemia, in which the erythrocytes are damaged or have abnormal shapes (schistocytes), combined with increased numbers of reticulocytes are indicative of hemolysis. Studies to detect the presence of autoantibodies (Direct Antiglobulin Test [DAT]) are performed and have 90% to 95% sensitivity in diagnosing AIHA.25 Bone marrow biopsy may be indicated in certain individuals. Evaluation for the underlying cause of the hemolysis is conducted.

Acquired hemolytic anemias are treated by removing the cause or treating the underlying disorder when possible. Folate is given to prevent megaloblastic anemia because long-term erythrocyte turnover increases folate requirements. Corticosteroids are used for initial treatment in most cases, with a response rate of over 80%.25 However some individuals relapse unless the underlying cause can be removed. The most commonly used second-line treatment is administration of rituximab (monoclonal antibody that reduces the number of B lymphocytes and thus antibody production), although it may be used as initial therapy for cold agglutinin AIHA. Third-line treatments may include splenectomy and the use of more potent immune-suppressive medications.25 Most treatments for AIHA confer an increased risk for infection, and individuals should be monitored carefully. Acute fulminating hemolytic anemia (hemolytic crisis) is treated with fluid and electrolyte replacement to prevent shock and renal damage, which may be caused by erythrocyte debris clogging the kidney tubules. Transfusions of blood products is reserved for severe life-threatening acute anemia. If repeated transfusion is required, an erythropoiesis-stimulating agent may be used.24

Myeloproliferative Red Cell Disorders

Hematologic dysfunction results from an overproduction of cells, as well as a deficiency. One or more hematopoietic lines may be overproduced in the marrow in response to exogenous (e.g., exposure to radiation, drugs) or endogenous (e.g., physiologic compensatory response, immune disorder) signals. Excessive red cell production is classified as polycythemia. Polycythemia exists in two forms: relative and absolute. Relative polycythemia results from hemoconcentration of the blood associated with dehydration that may be caused by decreased water intake, diarrhea, excessive vomiting, or increased use of diuretics. Its development is usually of minor consequence and resolves with fluid administration or treatment of underlying conditions.

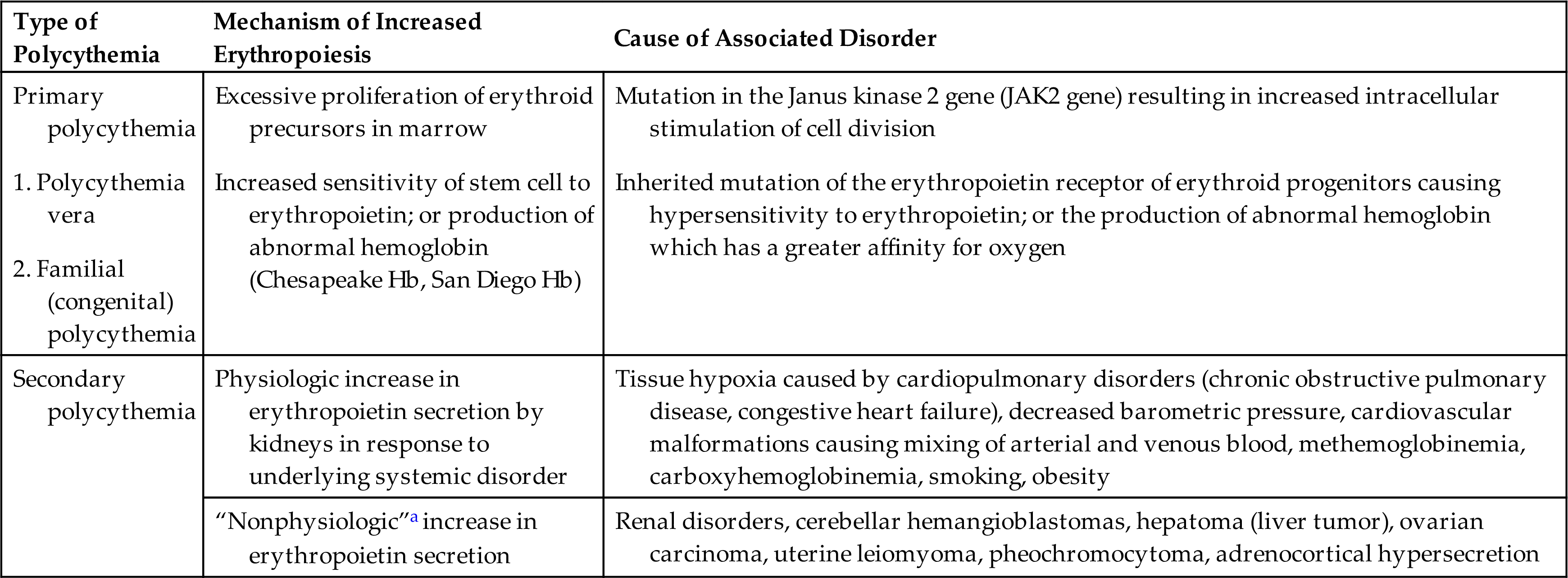

Absolute polycythemia consists of two types: primary and secondary (Table 29.5). Primary polycythemia comes in two forms. The more common form (but still rare) is polycythemia vera which occurs in older adults and is a type of malignancy of erythrocyte precursor cells in the bone marrow. Familial (congenital) polycythemia is most often caused by an autosomal dominant mutation of the erythropoietin receptor of erythroid progenitors causing hypersensitivity to erythropoietin and leading to increased rate of erythropoiesis.26 Familial polycythemia also can be caused by inherited defects in hemoglobin (e.g., Chesapeake Hb, San Diego Hb) which have a greater affinity for oxygen, causing isolated erythrocytosis in asymptomatic individuals. Secondary polycythemia is the most common type of polycythemia and is most often a physiologic response to hypoxia leading to increases in erythropoietin secretion. Chronic hypoxia is found in individuals living at higher altitudes (>10,000 ft), smokers with increased blood levels of carbon dioxide (CO), and individuals with COPD or heart failure, or both. Secondary polycythemia caused by nonphysiologic responses results from the production of erythropoietin by certain tumors (see Table 29.5).

Table 29.5

| Type of Polycythemia | Mechanism of Increased Erythropoiesis | Cause of Associated Disorder |

|---|---|---|

| 2. Familial (congenital) polycythemia | Mutation in the Janus kinase 2 gene (JAK2 gene) resulting in increased intracellular stimulation of cell division Inherited mutation of the erythropoietin receptor of erythroid progenitors causing hypersensitivity to erythropoietin; or the production of abnormal hemoglobin which has a greater affinity for oxygen | |

| Secondary polycythemia | Physiologic increase in erythropoietin secretion by kidneys in response to underlying systemic disorder | Tissue hypoxia caused by cardiopulmonary disorders (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure), decreased barometric pressure, cardiovascular malformations causing mixing of arterial and venous blood, methemoglobinemia, carboxyhemoglobinemia, smoking, obesity |

| “Nonphysiologic”a increase in erythropoietin secretion | Renal disorders, cerebellar hemangioblastomas, hepatoma (liver tumor), ovarian carcinoma, uterine leiomyoma, pheochromocytoma, adrenocortical hypersecretion |

aNonphysiologic means that there is no obvious physiologic explanation for hypersecretion of erythropoietin.

Polycythemia Vera

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a slowly growing blood cancer in which the bone marrow makes too many red blood cells. PV is quite rare, with a peak incidence between the ages of 60 and 80 years. However, PV has been observed in individuals younger than the age of 40. Males are twice as likely as females to develop PV. It is more common in whites of Eastern European Jewish ancestry. PV is rarely seen in children or in multiple members of a single family; however, an autosomal dominant form exists that causes increased secretion of erythropoietin. Median survival for PV is 15 years; however, the survival rate for individuals 40 and younger is 37 years.27

PV is one of several disorders collectively known as myeloid malignancies (Box 29.2). These disorders all result from abnormal regulation of the HSCs. Specifically, the common pathogenic feature is the presence of a mutation in the Janus kinase 2 gene (JAK2gene). Normally, the JAK2 gene makes a protein that helps the body produce blood cells. When JAK2 is mutated, there is an increased intracellular stimulation of cell division and an overproduction of blood cells.27 Because of numerous characteristics (e.g., overproduction of different blood cells, marrow hypercellularity, or fibrosis) shared by these disorders and a lack of specific molecular markers, the diagnosis can be quite challenging. The major characteristics shared by these disorders include (1) involvement of a hematopoietic progenitor cell, (2) overproduction of one or more of the formed elements in blood in the absence of a defined stimulus, (3) dominance by a transformed progenitor cell, (4) hypercellular bone marrow or fibrosis, (5) chromosomal (cytogenetic) abnormalities, (6) predisposition to thrombus formation and hemorrhage, and (7) spontaneous transformation to leukemia.

Pathophysiology

PV is a stem cell disorder with hyperplastic and neoplastic bone marrow alterations. It is characterized by an abnormal uncontrolled proliferation of red blood cells (frequently with increased levels of white blood cells [leukocytosis] and platelets [thrombocytosis]). The polycythemia is responsible for most of the clinical symptoms, including an increase in blood volume and viscosity. Proliferation of erythroid progenitors occurs in the bone marrow independent of the hormone erythropoietin. More than 95% of individuals with PV have an acquired mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 gene.27 Normal JAK2 protein increases the activity of the erythropoietin receptor and is self-regulatory so that JAK2 activity diminishes over time. The mutation associated with PV negates the self-regulatory activity of JAK2 so that the erythropoietin receptor is constantly active regardless of the level of erythropoietin. Overall, the mutated tyrosine kinases bypass normal controls, causing growth factor–independent proliferation and survival of marrow progenitors or precursor cells. The cause of the mutation is unknown.

Increased numbers of erythrocytes and other blood cells increase the blood viscosity. This alters blood flow and creates a hypercoagulable state that results in thrombotic occlusion of blood vessels. Tissue injury (ischemia) and death (infarction) are the outcomes of blood vessel blockage. These outcomes are directly correlated with hematocrit levels. Increases in numbers of thrombocytes, as well as production of dysfunctional platelets, also contribute to this hypercoagulable condition. Leukemia develops in approximately 3% of individuals with PA, and fibrotic transformation of the bone marrow limits survival in 15%.28

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of PV are a result of the increased red cell mass and hematocrit leading to increased blood volume and viscosity. This combined with thrombosis leads to symptoms of ischemia in vital organs (pain, hypoxia, decreased peripheral circulation). Circulatory alterations caused by the thick, sticky blood give rise to other manifestations, such as plethora (ruddy, red color of the face, hands, feet, ears, and mucous membranes) and engorgement of retinal and cerebral veins. Other symptoms may include headache, drowsiness, delirium, mania, psychotic depression, chorea, and visual disturbances. Individuals frequently have an enlarged spleen with abdominal pain and discomfort. Death from cerebral thrombosis is approximately five times greater in individuals with PV.

Cardiovascular function, despite the vascular alterations, remains relatively normal. Cardiac workload and output remain constant; however, increased blood volume does increase blood pressure. Coronary blood flow may be affected, precipitating angina, although cardiovascular infarctions are uncommon. Other cardiovascular manifestations include Raynaud phenomenon and thromboangiitis obliterans.

A unique feature of PV, and helpful in diagnosis, is the development of intense, painful itching that appears to be intensified by heat or exposure to water (aquagenic pruritus) so that individuals avoid exposure to water, particularly warm water when bathing or showering. The intensity of itching is related to the concentration of mast cells in the skin and is generally not responsive to antihistamines or topical lotions.

Evaluation and Treatment

PV may be suspected because of clinical features, such as a thrombotic event, splenomegaly, or aquagenic pruritus. Blood and laboratory findings confirm the diagnosis. Diagnostic criteria include a hemoglobin greater than 16.5 g/dL or a hematocrit greater than 49% in men and greater than 48% in women.27 Erythrocytes appear normal, but anisocytosis may be present. There also may be moderate increases in white blood cells and platelets. A bone marrow examination demonstrates proliferation of precursor cells and the presence of a JAK2 mutation which confirms the diagnosis. Serum erythropoietin levels are decreased.

Treatment of PV consists of reducing red cell proliferation and blood volume, controlling symptoms, and preventing clogging and clotting of the blood vessels. In low-risk individuals (e.g., those younger than age 60 or with no history of thrombosis and without risk factors for cardiovascular disease), the recommended therapy is phlebotomy (300 to 500 mL at a time to reduce erythrocytosis and blood volume) and low-dose aspirin. Frequent phlebotomies also reduce iron levels, a condition that impedes erythropoiesis.28

In high-risk PV, systemic anticoagulation is indicated. Hydroxyurea, a nonalkylating myelosuppressive, is the drug of choice for myelosuppression because of a reduced incidence to cause leukemia and thrombosis. IFN-α or busulfan are used when other forms of treatment have failed. Ruxolitinib inhibits the JAK2 pathway and is showing positive results in multiple studies.28

Iron Overload

Iron overload can be primary, as in hereditary hemochromatosis (HH), or secondary. The secondary causes of iron overload include anemias with inefficient erythropoiesis (e.g., AA), dietary iron overload, or conditions that require repeated blood transfusions or iron dextran injections.

Hereditary Hemochromatosis

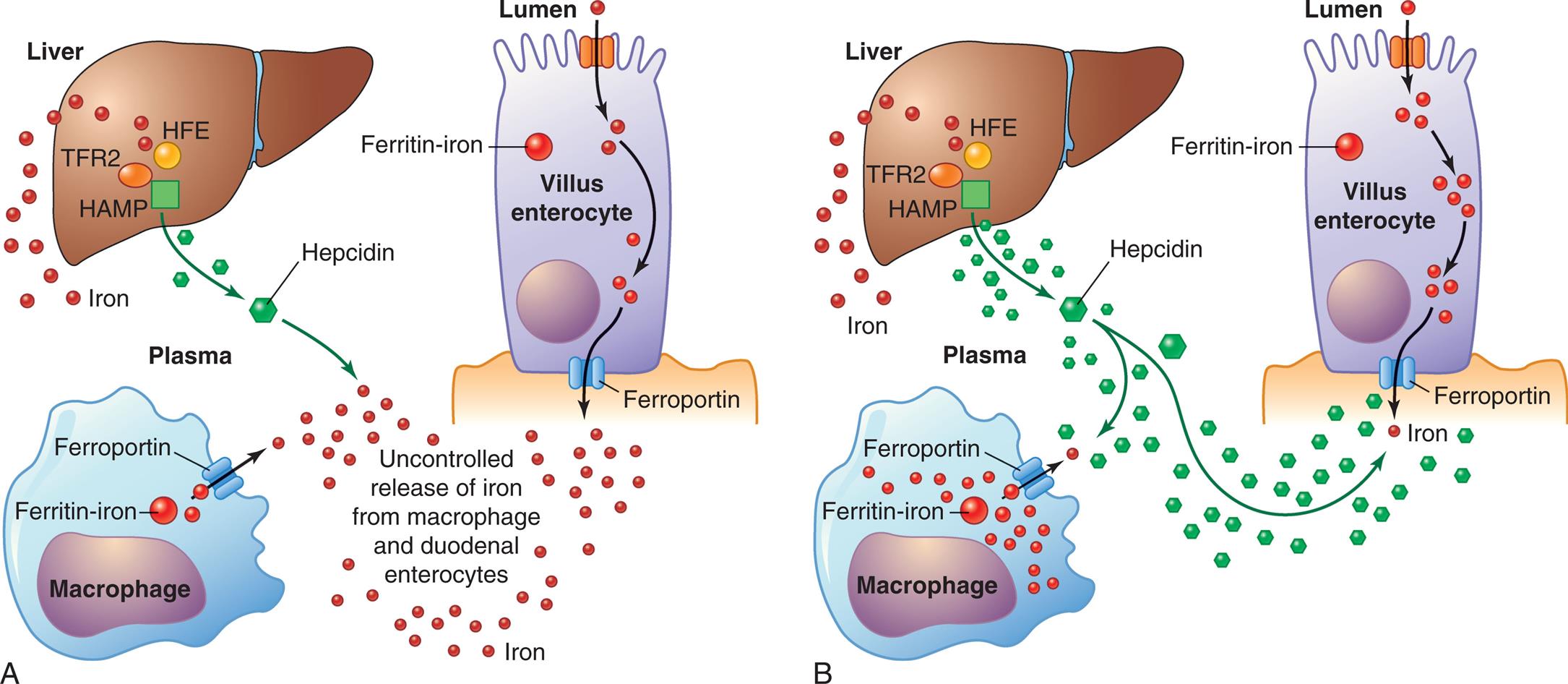

Hemochromatosis is caused by excessive iron absorption. Hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) is a common inherited iron overload disorder characterized by excessive absorption of iron. It is due to a deficiency of hepcidin or to decreased binding of hepcidin to ferroportin, the transmembrane protein that exports iron outside the cell (Fig. 29.9).29 HH is characterized by increased iron absorption from the GI tract, with subsequent tissue iron deposition. Excess iron is deposited first in the liver and pancreas, followed by the heart, joints, and endocrine glands. Excess iron causes tissue damage that can lead to diseases such as cirrhosis, diabetes, heart failure, arthropathies, and impotence.

(A) Mutations in genes affecting HFE, TFR2, or HAMP lead to decreased levels of hepcidin causing excessive absorption of iron. (B) Mutations to ferroportin cause decreased binding of hepcidin and iron accumulation within cells. HAMP, Hepatic antimicrobial protein; HFE, human homeostatic iron regulator protein; TFR2, transferrin receptor 2. (Adapted from Pietrangelo A. Hereditary hemochromatosis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA). Molecular Cell Research, 2006;1763(7):700–710.)

Left panel, A. The illustration shows a macrophage, the liver, and a lumen. The lumen and macrophage release iron not through the ferroportin. Mutations affecting T F R 2, H F E, and H A M P in the liver decrease hepcidin levels. Liver also releases iron. All factors lead to uncontrolled release of iron from macrophage and duodenal enterocytes. Right panel, B. The illustration shows macrophage, the liver, and a lumen. Mutations in the ferroportin of the macrophage and lumen result in the storage of iron within the cells. Normal hepcidin levels regulate the absorption of iron by the liver.

Pathophysiology

Different forms of HH result from mutations in various genes that play important roles in regulating absorption, transport, and storage of iron. HH is classified by type (1, 2, 3, and 4) based on which proteins involved in iron homeostasis are affected. Type 1 HH is the most frequent form and is characterized by one of two mutations of the human homeostatic iron regulator (HFE) gene. These mutations result in decreased synthesis of hepcidin. Hepcidin is a hormone secreted by the liver in response to increased serum iron, and it inhibits iron absorption from the intestine by degrading ferroportin-1. (see Chapter 28). Most affected individuals have a homozygous C282Y mutations in the HFE gene (type 1a).30 Less common is H63D mutation, which by itself does not cause significant iron overload, but may become clinically significant when associated with excessive alcohol intake or hepatitis C infection or may act as a cofactor in combination with C282Y. This combined C282Y/H63D genotype is classified as HH type 1b.29 The other HH genotypes have a much lower prevalence. Type 2 HH, also called juvenile hemochromatosis, is associated with mutations in either the HJV gene or the hepatic antimicrobial protein (HAMP) gene leading to hepcidin deficiency. Type 2 is the most severe form of primary iron overload and develops in younger individuals. Type 3 HH is associated with mutations in the transferrin receptor 2 (TFR2) gene, also leading to hepcidin deficiency. Type 4 A HH results from autosomal dominant mutations in the ferroportin gene (SLC40A1) These mutations disrupt the export function of ferroportin despite normal levels of hepcidin. Intracellular iron rises in association with low levels of plasma iron and normal levels of transferrin saturation but elevated levels of serum transferrin. Type 4B HH results from resistance of ferroportin to hepcidin.29

In all types of HH, iron accumulates in tissues and organs disrupting their normal function.30 In the liver, this accumulation of iron may lead to the development of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.31 Cardiac complications are the second-leading cause of death in HH and include cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, and heart failure. HH injures the pancreatic β-islet cells and contributes to the development of hepatic insulin resistance leading to diabetes in 13% to 23% of affected individuals.29 Iron deposits in the skin lead to increased melanin deposition, causing bronzing. Arthropathy most commonly involves the second and third metacarpophalangeal joints.

Clinical Manifestations