Alterations of Renal and Urinary Tract Function

Julia L. Rogers

The renal system plays a major role in homeostasis by filtering nearly 200 L of blood every 24 hours. Approximately 1 L of filtered fluid is converted into urine and excreted through micturition per day. Because the kidneys filter the blood, the renal system is directly linked to every other organ system. A variety of disorders affects renal function by inhibiting the kidney’s ability to regulate plasma volume and osmolality. Disease may be limited to only the kidney and urinary tract or may include systemic diseases that cause acute kidney injury (AKI), chronic kidney disease (CKD), or difficulty eliminating urine (e.g., infection, neurologic injury, or diabetes mellitus). Infection of the kidney or urinary tract is the most common disorder affecting renal function. Stones, tumors, inflammation, or consequences of medical procedures can obstruct and/or cause injury to the upper or lower urinary tract (LUT). Renal injury, whether acute or chronic, can affect other organs and become life-threatening.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Rogers/pathophysiology/

Urinary Tract Obstruction

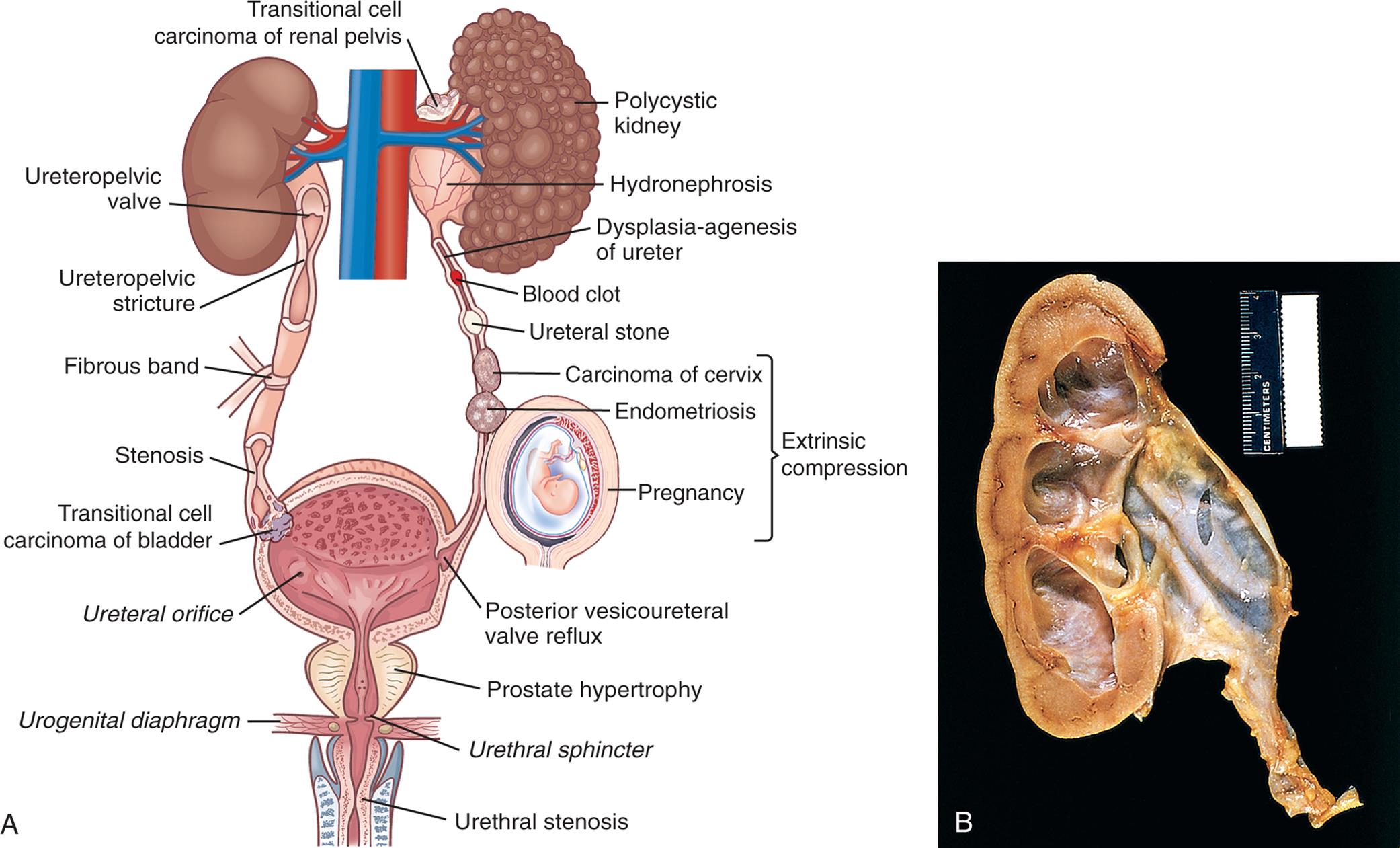

Urinary tract obstruction is an anatomic (structural) or functional abnormality that causes interference with the flow of urine at any site along the urinary tract (Fig. 38.1). An obstruction impedes urine flow, increases hydrostatic pressure, dilates structures proximal to the blockage, which increases risk of infection, and compromises renal function. Anatomic changes in the urinary system caused by obstruction are referred to as an obstructive uropathy, which may be acute or chronic, partial, or complete, and unilateral or bilateral. The severity of an obstructive uropathy is determined by the:

(A) Major sites of urinary tract obstruction. (B) Hydronephrosis of the kidney. There is marked dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces with thinning of the overlying cortex and medulla due to compression atrophy. (B, From Kumar V, et al. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, 10th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2021.)

Left panel, A. The illustration shows the urinary system. The followings structures are labeled, clockwise from the top: transitional cell carcinoma of renal pelvis, polycystic kidney, hydronephrosis, dysplasia-agenesis of ureter, blood clot, ureteral stone, extrinsic compression (carcinoma of cervix, endometriosis, and pregnancy), posterior vesicoureteral valve reflux, prostate hypertrophy, urethral sphincter, urethral stenosis, urogenital diaphragm, ureteral orifice, transitional cell carcinoma of bladder, stenosis, fibrous band, ureteropelvic stricture, and ureteropelvic valve.

Obstructions may be relieved, or partially alleviated, by correction of the obstruction, although permanent impairments such as hydronephrosis occur if a complete or partial obstruction persists over a period of weeks to months or longer.

Upper Urinary Tract Obstruction

A stricture or compression of the calyx, ureteropelvic, or ureterovesical (ureter-bladder) junction is a common cause of upper urinary tract obstructions and is commonly caused by kidney stones (calculi). Ureteral compressions or blockages can be caused from an aberrant vessel, tumor, stone, or abdominal inflammation and scarring (retroperitoneal fibrosis).1 The most common cause in children is a congenital anomaly (see Chapter 39); in young adults, the common cause is renal calculi; and in older adults, renal calculi, ureteral strictures, and tumors are more common.

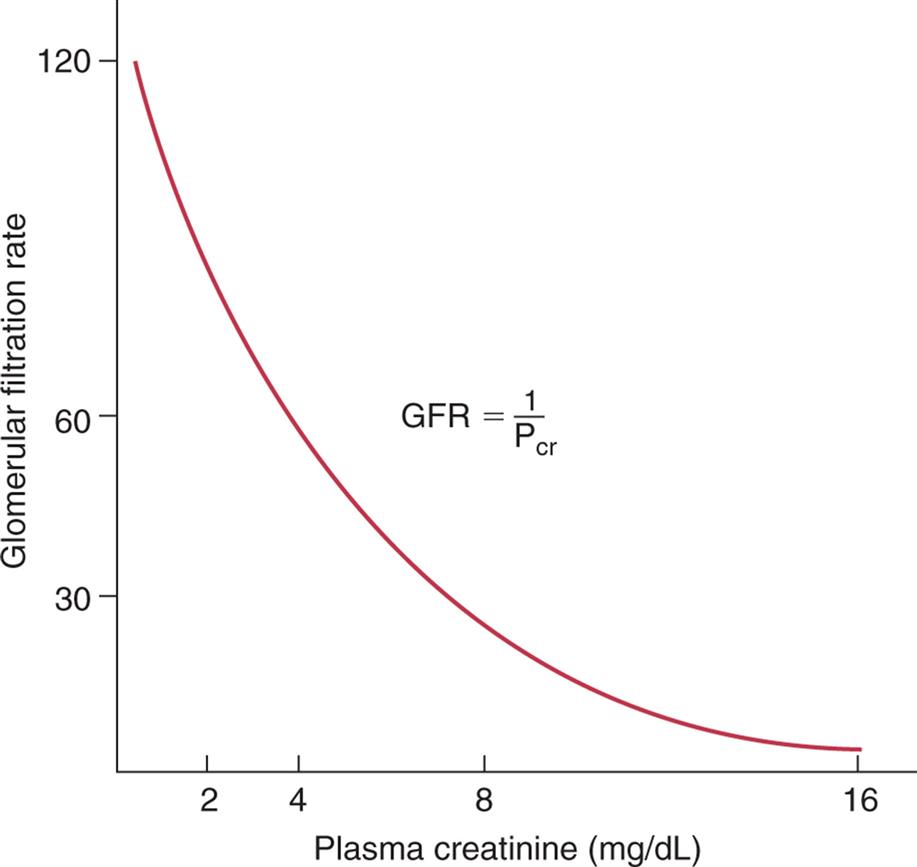

Obstruction of the upper urinary tract causes a “backing up” of urine and dilation of the ureter, renal pelvis, calyces, and renal parenchyma proximal to the site of urinary blockage. Dilation of the ureter is referred to as hydroureter (accumulation of urine in the ureter). Dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces proximal to a blockage is referred to as hydronephrosis or ureterohydronephrosis (dilation of both the ureter and the pelvicaliceal system) (see Fig. 38.1B). The backup of urine into the Bowman space from an obstruction opposes the hydrostatic pressure of glomerular filtration and decreases the glomerular filtration rate (GFR).1 Unless the obstruction is relieved, the dilation leads to tubulointerstitial fibrosis, which damages renal nephrons and can lead to CKD.

Tubulointerstitial fibrosis is the deposition of excessive amounts of extracellular matrix (collagen and other proteins) by activated inflammatory cells including macrophages and myofibroblasts with associated areas of tubular atrophy.2 Tubulointerstitial fibrosis occurs with kidney injury including obstructive uropathies. Although deposition of extracellular matrix is a normal process of kidney repair and maintenance, activation of inflammatory cells and production of growth factors, such as transforming growth factor-beta-1 (TGF-β1), promotes the process of tubulointerstitial fibrosis and irreversible kidney damage.3

Apoptosis is a normal process that the body uses to replace damaged or senescent cells with new ones (see Chapter 1). An imbalance in growth factors provoked by obstruction contributes to excess cellular destruction with a transition from apoptosis to necrosis and inflammation, ultimately resulting in the loss of functioning nephrons.4

The magnitude of this damage, and the kidney’s ability to recover normal homeostatic function, is affected by the severity and duration of the obstruction. With complete obstruction, damage to the renal tubules and compression of the renal vasculature occur in a matter of hours, and irreversible damage occurs within 3 to 4 weeks. Nevertheless, even in the face of a complete obstruction, the human kidney may recover at least partial homeostatic function provided the blockage is removed. Recovery can take up to 3 months.5

When there is unilateral obstruction, the body is able to partially counteract the negative consequences by a process called compensatory hypertrophy and hyperfunction. The compensatory response is guided by growth factors that cause the unobstructed kidney to increase the size and function of individual glomeruli and tubules, but not the total number of functioning nephrons. Consequently, the obstructed kidney can remain silent for a long time. Partial obstruction that is not relieved, in the absence of renal infection, leads to more subtle, but ultimately permanent impairments including loss of the kidney's ability to concentrate urine, reabsorb bicarbonate, excrete ammonia, and regulate metabolic acid-base and fluid and electrolyte balance. The process is reversible when relief of obstruction results in recovery of function by the obstructed kidney. The ability of the body to engage in compensatory hypertrophy and hyperfunction diminishes with age. Complete bilateral obstruction causes anuria because the retrograde increase in tubular hydrostatic pressure completely opposes glomerular filtration.

Relief of upper urinary tract obstruction is usually followed by a brief period of diuresis, commonly called postobstructive diuresis. Postobstructive diuresis is a physiologic response and is typically mild, representing a restoration of fluid and electrolyte imbalance caused by retention of fluid related to the obstructive uropathy. Occasionally, relief of obstruction will cause rapid excretion of large volumes of water, sodium, or other electrolytes, resulting in a urine output of 200 mL/h for two consecutive hours or more than 3 L in 24 hours. Minimal normal daily urine output is approximately 720 mL/day.6 Rapid postobstructive diuresis causes dehydration and fluid and electrolyte imbalances that must be promptly corrected. Risk factors for severe postobstructive diuresis include chronic, bilateral obstruction; impairment of one or both kidneys’ ability to concentrate urine or reabsorb sodium (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus); hypertension; edema and weight gain; congestive heart failure; and uremic encephalopathy.

Nephrolithiasis

Nephrolithiasis, also commonly known as kidney stones or renal calculi, are masses of crystals, protein, or other substances that are a common cause of urinary tract obstruction in adults. Stones can be located anywhere along the urinary tract including in the kidneys, ureters, and urinary bladder. However, the favored sites of stone formation are in the renal calyces, renal pelvis, and bladder. Stones are unilateral in about 80% of individuals. The prevalence of kidney stones in the United States is approximately 11% in males and 7% in females with an incidence of about 1% per year.7 The cumulative risk of recurrence at 5 years is approximately 53% overall, with a lower rate of 26% for those with a single stone episode.8 The risk of stone formation is influenced by a number of factors, including age, sex, race, geographic location, seasonal factors, fluid intake, diet, occupation, and genetic predisposition.9 Diseases that predispose individuals for stone formation are urinary tract infection (UTI), hypertension, atherosclerosis, metabolic syndrome, obesity, and type 2 diabetes.10 While stones are more prevalent in males before the age of 50 years, there is increasing incidence seen in females. Geographic location influences the risk of stone formation because of indirect factors. Warmer climates with high humidity and rainfall influence a person’s fluid intake and dietary patterns. Persons who regularly consume an adequate volume of water are at reduced risk when compared with persons who consume lower volumes of water.9

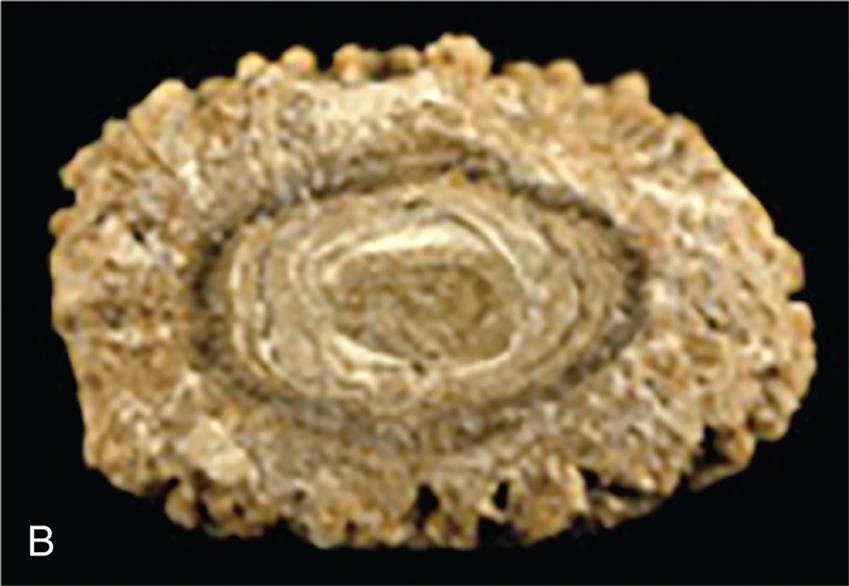

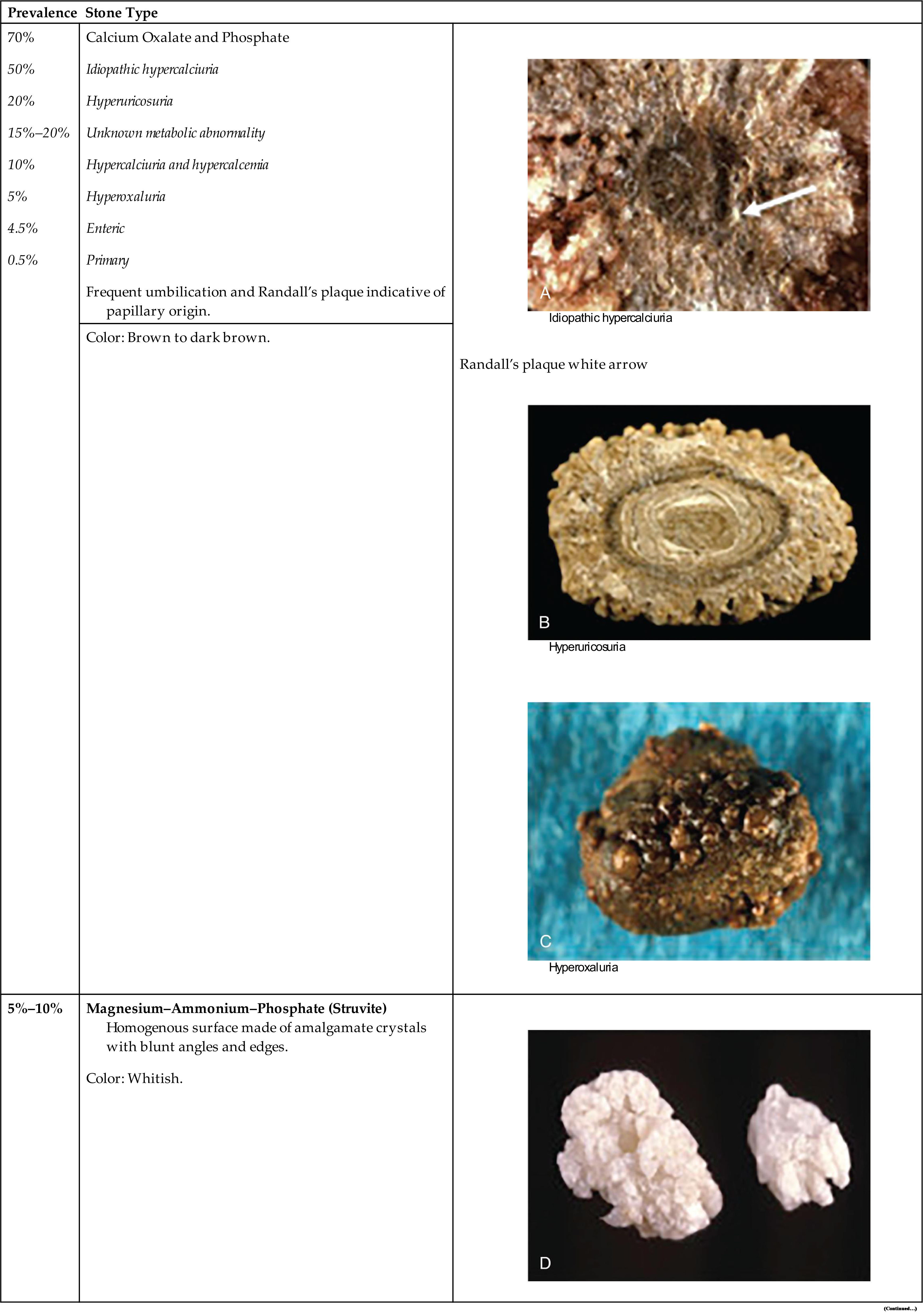

Stones are classified according to the primary minerals (salts) that make up the stones. The most common stone types include calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate (70% to 80%), struvite (magnesium–ammonium–phosphate) (5% to 10%), and uric acid (5% to 10%) (Table 38.1).11 Cystine stones are rare (≤2%), and so are stones that are formed from the metabolic effects of some medications (e.g., atazanavir, ceftriaxone, and N-acetyl-sulfadiazine) in individuals treated for a lengthy period of time for chronic diseases.12,13

Table 38.1

Pictures in right column from Daudon M, Dessombz A, Frochot V, et al. Comprehensive morpho-constitutional analysis of urinary stones improves etiological diagnosis and therapeutic strategy of nephrolithiasis. Comptes Rendus Chimie, 2016;19(11–12):1470–1491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crci.2016.05.008.

Stones are also classified according to location and size. Staghorn calculi are large and fill the minor and major calyces. Nonstaghorn calculi are of variable size but tend to be smaller and are located in the renal calyces, renal pelvis, or at various sites along the ureter.

Pathophysiology

Stone formation is complex and related to:

- 1. supersaturation of one or more salts in the urine,

- 2. precipitation of the salts from a liquid to a solid state (crystals),

- 3. growth through crystallization or agglomeration (sometimes called aggregation), and

- 4. the presence or absence of stone inhibitors (e.g., uromodulin [Tamm-Horsfall protein]).

Supersaturation is the presence of a higher concentration of a solute (salt) within a solvent (in this case, the urine) than can be dissolved. Human urine contains many ions capable of precipitating from solution and forming a variety of salts. The salts form crystals that are retained and grow into stones. Crystallization is the process by which crystals grow from a small nucleus, or nidus, to larger stones in the presence of supersaturated urine. Although supersaturation is essential for free stone formation, the urine need not remain continuously supersaturated for a stone to grow once its nucleus has precipitated from solution. Intermittent periods of supersaturation after the ingestion of a meal or during times of dehydration from limited oral intake or secondary to continued use of diuretics are sufficient for stone growth in many individuals. In addition, the renal tubules and papillae have many surfaces that may attract a crystalline nidus (known as a Randall plaque) and add biologic material (matrix), forming a stone. Matrix is an organic material (i.e., mucoprotein) in which the components of a kidney stone are embedded. Randall plaques start in the suburothelial layer and gradually grow until they break through into the renal pelvis. Once in continuous contact with urine, layers of calcium oxalate typically start to form on the calcium phosphate nidus (see Table 38.1).14 The pH of the urine influences the risk of precipitation and calculus formation. An alkaline urinary pH (pH > 7.0) significantly increases the risk of calcium phosphate stone and struvite stone formation, whereas acidic urine (pH < 5.0) increases the risk of uric acid stone formation. Cystine and xanthine also precipitate more readily in acidic urine.

Substances capable of inhibiting stone or crystal growth include potassium citrate, Tamm-Horsfall protein, pyrophosphate, and magnesium.15 These substances normally reduce the risk of calcium phosphate or calcium oxalate precipitation in the urine and prevent subsequent stone formation.

Retention of crystal particles occurs primarily at the papillary collecting ducts. Most crystals are flushed from the tract through the normal flow of urine. Urinary stasis (e.g., from benign prostatic hyperplasia, neurogenic bladder), anatomic abnormalities (strictures), or inflamed epithelium within the urinary tract may prevent prompt flushing of crystals from the system, thus increasing the risk of stone formation.

The size of a stone determines the likelihood that it will pass through the urinary tract and be excreted through micturition. Stones smaller than 5 mm have about a 50% chance of spontaneous (painful) passage, whereas stones that are larger than 1 cm have almost no chance of spontaneous passage.16

Both genetic and environmental factors may increase the susceptibility of calcium stones. Most affected individuals have idiopathic calcium oxalate urolithiasis (ICOU), a condition the exact etiology of which has not yet been determined. Stones can form freely in supersaturated urine or detach from interstitial sites of formation (e.g., from Randall plaque). Hypercalciuria, hyperoxaluria, hyperuricosuria, hypocitraturia, mild renal tubular acidosis, crystal growth inhibitor deficiencies, and alkaline urine are associated with calcium stone formation. Hypercalciuria and hyperoxaluria are usually attributable to intestinal hyperabsorption and less commonly to a defect in renal calcium reabsorption. Hyperparathyroidism and bone demineralization associated with prolonged immobilization are also known to cause hypercalciuria.17

Struvite stones primarily contain magnesium, ammonium, and phosphate as well as varying levels of a matrix. Matrix forms in an alkaline urine and during infection with a urease-producing bacterial pathogen, such as a Proteus, Klebsiella, or Pseudomonas.18 Struvite calculi may grow quite large and branch into a staghorn configuration (staghorn calculus) that approximates the pelvicaliceal collecting system. Women are at greater risk for struvite stones because they have an increased incidence of UTI.

Uric acid stones occur in persons who excrete excessive uric acid in the urine, such as those with gouty arthritis. Uric acid is primarily a product of biosynthesis of endogenous purines and is secondarily affected by consumption of purines (e.g., meat and beer) in the diet. A consistently acidic urine greatly increases this risk, including defective excretion. Cystinuria and xanthinuria are genetic disorders of amino acid metabolism, and their excess in urine can cause cystine or xanthine stone formation in the presence of acidic urine.19

Clinical Manifestations

Renal colic is pain related to dilation and spasms of smooth muscle related to ureteral obstruction. Moderate to severe pain often originates in the flank and radiates to the groin, and usually indicates obstruction of the renal pelvis or proximal ureter. Colic that radiates to the lateral flank or lower abdomen typically indicates obstruction in the midureter. Bothersome LUT symptoms (urinary urgency, frequency, incontinence) indicate obstruction of the lower ureter or ureterovesical junction. The pain can be incapacitating and may be accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Gross or microscopic hematuria may be present.

Evaluation and Treatment

The evaluation and diagnosis of nephrolithiasis is based on presenting symptoms and history combined with a focused physical assessment. Imaging studies determine the location of the stone, severity of obstruction, and associated obstructive uropathy. Imaging of kidney stones can include plain abdominal radiography, ultrasound, intravenous pyelography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The history queries dietary habits, age of the first stone episode, stone analysis, and presence of complicating factors, including hyperparathyroidism or recent gastrointestinal or genitourinary surgery. Urinalysis (including pH) is obtained, and a 24-hour urine is completed to identify calcium oxalate, calcium citrate, and other significant constituents. In addition, every effort is made to retrieve and analyze stones that are passed spontaneously or retrieved through aggressive intervention. To diagnose and manage underlying metabolic disorders, additional tests are completed for those with suspected hyperparathyroidism (elevated serum calcium levels), cystine calculi, or uric acid (high purine diet) stones.

The goals of treatment are to manage acute pain, promote stone passage, reduce the size of stones already formed, and prevent new stone formation.20 The components of treatment include:

- 1. managing pain (can require narcotic medication),

- 2. reducing the concentration of stone-forming substances by increasing urine flow rate with high fluid intake,

- 3. adjusting the pH of the urine (e.g., make it more alkaline with potassium citrate administration or more acid with potassium acid phosphate),

- 4. decreasing the amount of stone-forming substances in the urine by decreasing dietary intake or endogenous production or by altering urine pH, and

- 5. removing stones using percutaneous nephrolithotomy, ureteroscopy, or ultrasonic or laser lithotripsy to fragment stones for excretion in the urine.21

Obstructing kidney stones with a suspected proximal UTI are urologic emergencies requiring emergent decompression, stone removal, and antibiotics.22 Prevention of recurrent stones includes increasing fluid intake to generate 2.5 L of urine per day, avoiding intake of colas and other soft drinks acidified with phosphoric acid, avoiding dietary oxalate (e.g., chocolate, beets, nuts, rhubarb, spinach, strawberries, tea, wheat bran), eating less animal protein, and limiting sodium intake. Maintaining a dietary calcium intake of 1000 to 1200 mg/day is helpful for calcium stone prevention. Potassium citrate may be used to prevent calcium stone aggregation and to raise urinary pH.23

Lower Urinary Tract Obstruction

Obstructions of the LUT are inherently caused by a structural or anatomic disorder or an alteration in neurologic function (neurogenic bladder). These disorders are related to alterations of urine storage in the bladder or emptying of urine through the bladder outlet. Incontinence is a common symptom associated with LUT obstructions. The types of incontinence are summarized in Table 38.2.

Table 38.2

Data from: Wyndaele M, Hashim H. Pathophysiology of urinary incontinence. Surgery (Oxford), 2020;38(4): 185–190.

Anatomic Obstructions to Urine Flow

Anatomic causes of resistance to urine flow include urethral stricture, prostatic enlargement in men, pelvic prolapse (bladder and uterus) in women, and tumor compression. A urethral stricture is a narrowing of its lumen and occurs when infection, injury, or surgical manipulation produces a scar that reduces the caliber of the urethra. The severity of obstruction is influenced by its location within the urethra, its length, and the severity of the stricture. Strictures that are longer than 1 centimeter and in the proximal urethra cause more severe obstruction. They are more common in men because of a longer urethra (see Chapter 26).24 Urethral stricture is treated with urethral dilation accomplished by using a steel instrument shaped like a catheter (urethral sound) or a series of incrementally increasing catheter-like tubes (filiforms and followers). Long, dense strictures typically require surgical repair (urethroplasty) to prevent recurrence. Prostate enlargement is caused by acute inflammation, benign prostatic hyperplasia, or prostate cancer (see Chapter 26). Severe pelvic organ prolapse (see Chapter 25) in a woman causes bladder outlet obstruction when a cystocele (the downward protrusion/herniation of the bladder into the vagina) or the uterus descends into the vagina below the level of the urethral outlet. In men, the bladder may rarely herniate into the scrotum, causing a similar type of obstruction. Each of these disorders can cause compression of the urethra with obstruction to urine flow.

Partial obstruction of the bladder outlet or urethra initially causes an increase in the force of detrusor contraction. If the obstruction persists, afferent nerves within the bladder wall are adversely affected, leading to urinary urgency and, in some cases, overactive detrusor contractions (a myogenic cause of overactive bladder). When obstruction persists, there is an increased deposition of collagen within the smooth muscle bundles of the detrusor muscle (trabeculation). Ultimately, the bladder wall loses its ability to stretch and accommodate urine, a condition called low bladder wall compliance (loss of elasticity), and the detrusor loses its ability to contract efficiently, resulting in urine retention. This underactive bladder (UAB) syndrome can also occur as a consequence of bladder radiation treatment. Low bladder wall compliance chronically elevates intravesicular pressure, increasing the likelihood of hydroureter, hydronephrosis, impaired renal function, incontinence, and UTI.

Symptoms of obstruction include:

- 1. frequent daytime voiding (micturition more than every 2 hours while awake);

- 2. nocturia (awakening more than once each night to urinate for adults younger than 65 years of age or more than twice for older adults);

- 3. poor force of stream;

- 4. intermittency of urinary stream;

- 5. bothersome urinary urgency, often combined with hesitancy; and

- 6. feelings of incomplete bladder emptying despite micturition.

Overactive and Underactive Bladder Syndrome

Overactive bladder syndrome (OAB) is a dysfunction of urine storage with nonspecific symptoms characterized by urinary urgency, frequency, and nocturia with or without incontinence in the absence of UTI or other known pathology (e.g., neurologic disorders). OAB affects a significant number of adults (approximately 16%).25 The specific cause is not clearly known and several mechanisms could be involved including myogenic or neurogenic alterations in sensory and motor function.26 The symptoms are usually associated with involuntary contractions of the detrusor muscle during the bladder-filling phase, often resulting in urge incontinence and nocturia. Risk factors in women include vaginal birth with episiotomy or use of forceps, surgery for pelvic organ prolapse, and decreased estrogen associated with menopause or hysterectomy. Loss of estrogen results in thinning and loss of urethral muscle strength. Risk factors in men include enlarged prostate with urinary obstruction and surgical treatment for prostate cancer. Risk factors include the use of diuretics, antidepressants, alpha-agonists, beta-antagonists, sedatives, anticholinergics, and analgesics.

Both behavioral and pharmacologic therapy are first- and second-line treatments for OAB. Behavioral therapy includes pelvic floor (Kegel) exercises (detrusor contraction can be inhibited by pelvic floor muscle contraction providing time to get to the toilet), bladder training with timed voiding, management of fluid intake and use of caffeine and alcohol, managing constipation, and biofeedback techniques. Drug therapy to manage incontinence includes topical vaginal estrogen in women and drugs that increase urethral sphincter contraction or relax the bladder wall.

Because the parasympathetic nervous system controls detrusor muscle contraction with cholinergic (muscarinic) signals and the bladder neck consists of circular smooth muscle with α-adrenergic innervation, OAB may be managed by anticholinergic therapy (antimuscarinic) and adrenergic medications. Anticholinergics increase urethral pressure, and β3-adrenergic agonists relax the bladder wall, increasing bladder capacity. These medications must be monitored closely for adverse side effects. When these therapies are not successful, neuromodulation therapy is considered, including intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) (inhibits release of acetylcholine), peripheral tibial nerve stimulation, and sacral neuromodulation. Low bladder wall compliance (loss of elasticity) may be managed by antimuscarinic drugs, intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxin A injections, and intermittent catheterization.27 OAB syndrome should be discussed during health assessments; however, many individuals are reluctant to discuss OAB syndrome with their health care provider. Untreated OAB is an economic burden, impairs health and quality of life, and causes symptoms such as skin breakdown because of leakage, sleep disturbance, fall-related injuries, depression, prolonged hospital stays, and admission to long-term care facilities.

UAB syndrome is a voiding dysfunction characterized by the International Continence Society Working Group as bladder contraction of reduced strength and/or duration, resulting in prolonged bladder emptying or a failure to achieve complete bladder emptying, or both, within a normal time span. Symptoms include a slow urinary stream, hesitancy, and straining to void, with or without a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying and dribbling.28 Disruption of bladder innervation can occur with spinal cord injury, stroke, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, and diabetic neuropathy. Aging can be a contributing factor. The symptoms may be indistinguishable from symptoms of LUT obstruction, including weak stream, intermittency, hesitancy, and straining to void. In some cases, UAB and OAB may occur together with detrusor overactivity during storage but poor detrusor contraction in the voiding phase. Urodynamic studies are required for evaluation. Treatment depends on the cause of the disorder and may include sacral neuromodulation, drugs that increase bladder contractility, and/or drugs that induce urethral relaxation.29

Evaluation and Treatment

Diagnosis of LUT obstructions requires a detailed history; physical examination, including neurologic and pelvic examinations; urinalysis; and determining if pathologic causes of urgency and frequency, such as prostatic enlargement, pelvic organ prolapse, urethral strictures, and neurologic disorders or systemic disease, are present. Diaries and questionnaires are helpful to determine the pattern and severity of incontinence. However, no symptom or cluster of symptoms has been identified that accurately differentiates the various causes of these disorders. For example, symptoms such as urgency, urge incontinence, frequent urination, and nocturia may develop because of overactive bladder or either increased or decreased bladder outlet resistance. Reduced resistance is associated with the symptom of stress incontinence (incontinence with coughing or sneezing), and symptoms of increased resistance are similar to bladder outlet obstruction, including poor force of urinary stream, hesitancy, and feelings of incomplete bladder emptying. Various urodynamic tests (Box 38.1) assist with the evaluation of how efficient the bladder, sphincters, and urethra are in storing and releasing urine. An evaluation of renal function, including functional imaging studies and measurement of serum creatinine (SCr) level, is completed particularly when the obstruction is severe and associated with elevated residual urine or UTI.

Neurogenic Bladder

Neurogenic bladder is a general term for bladder dysfunction caused by neurologic disorders (Table 38.3).30 The types of dysfunctions are related to the sites in the nervous system that control sensory and motor bladder function (Fig. 38.2). Lesions in the upper motor neurons of the brain and spinal cord result in detrusor hyperreflexia (overactive bladder) and bladder dyssynergia (loss of coordinated neuromuscular contraction). Lesions in the sacral area of the spinal cord or peripheral nerves result in underactive, hypotonic, or atonic (flaccid) bladder function, often with loss of bladder sensation. (See Chapter 15 for upper and lower motor neuron function.)

Table 38.3

An illustration shows the sites of neurologic injury associated with neurogenic bladder. The illustration shows and labels the following structures, from the top to the bottom: the detrusor motor area, lesions above C 2, the pontine micturition center, lesions above S 1 and below C 2, lesions below S 1, and bladder. Reflex urinary incontinence in the detrusor motor area is detrusor hyperreflexia. The diseases (upper motor neuron lesion) include stroke, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, hydrocephalus, cerebral palsy, Alzheimer disease, and brain tumors. Reflex urinary incontinence in the pontine micturition center is detrusor hyperreflexia with vesicosphincter dyssynergia. The diseases (upper motor neuron lesions) include spinal cord injury (C 2 to T 12), multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and disk problems. Reflex urinary incontinence in the bladder is detrusor areflexia, with or without urethral sphincter incompetence. The diseases (lower motor neuron lesions) include myelodysplasia, peripheral polyneuropathies, multiple sclerosis, tabes dorsalis, spinal injury (T 12 to S), cauda equina syndrome, and herpes simplex or zoster.

Neurologic disorders that develop above the pontine micturition center (located near the posterior pons) result in detrusor (bladder muscle) hyperreflexia (overactivity), also known as an uninhibited or reflex bladder or neurogenic overactive bladder. This is an upper motor neuron disorder in which the bladder empties automatically (without voluntary control) when it becomes full and the urethral sphincter functions normally. Because the pontine micturition center remains intact, there is coordination between detrusor muscle contraction and relaxation of the urethral sphincter. Stroke, traumatic brain injury, dementia, and brain tumors are examples of disorders that result in detrusor hyperreflexia. Symptoms include urine leakage and incontinence.

Neurologic lesions that occur below the pontine micturition center but above the sacral micturition center (between C2 and S1) are also upper motor neuron lesions and result in detrusor sphincter dyssynergia (detrusor hyperreflexia with vesicosphincter dyssynergia) (loss of coordinated function between the bladder and sphincter). There is loss of pontine coordination of detrusor muscle contraction and external sphincter relaxation, so both the bladder and the sphincter are contracting at the same time (dyssynergia), causing a functional obstruction of the bladder outlet. Spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and vertebral disk problems are causes of this disorder. There is diminished bladder relaxation during storage with small urine volumes and high intravesicular (inside the bladder) pressures. The result is an OAB with symptoms of frequency, urgency, urge incontinence, and increased risk for UTI. Diagnosis includes a medical history, physical examination, urinalysis, and urodynamic testing. Detrusor sphincter dyssynergia may be managed by intermittent catheterization in combination with higher dose antimuscarinic drugs to prevent overactive detrusor contractions and associated dyssynergia, while ensuring regular, complete bladder evacuation by catheterization. Transurethral botulinum toxin A injection has shown temporary efficacy in reducing bladder outlet obstruction. Transurethral sphincterotomy can be beneficial.31

Neurologic lesions involving the sacral micturition center (below S1, also termed cauda equina syndrome) or peripheral nerve lesions result in detrusor areflexia (acontractile detrusor, atonic bladder, or UAB), a lower motor neuron disorder. The atonic bladder causes retention of urine and distention with stress and overflow incontinence. There is prolonged urination time with or without a sensation of incomplete bladder emptying, usually with hesitancy, reduced sensation on filling, and a slow stream. If the sensory innervation of the bladder is intact, the full bladder will be sensed but the detrusor may not contract. Myelodysplasia, multiple sclerosis, tabes dorsalis (deterioration of the posterior columns of the spinal cord associated with untreated syphilis), spinal cord injury, and peripheral polyneuropathies (i.e., diabetic neuropathy) are associated with this disorder.

Diagnosis includes disease history, clinical examination, urinalysis, and urodynamic studies (see Box 38.1). Bethanechol chloride (Urecholine) is a cholinergic agent (muscarinic agonist) that stimulates the bladder to empty and can be helpful in some cases. Intermittent catheterization or indwelling catheters are commonly required.

Tumors

Kidney (Renal) Tumors

Kidney (Renal) tumors were estimated at 76,080 (4%) of new cancer cases and 13,780 deaths for 2021.32 Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) (also known as renal cell adenocarcinoma) usually occurs in men (about three times more often than in women) between 50 and 60 years of age. Risk factors include cigarette smoking, obesity, and uncontrolled hypertension. With surgical resection, 5-year survival is about 93% for stage I (encapsulated) cancer.

Pathophysiology

There are several different types of RCCs. They are classified according to subtypes and extent of metastasis. Clear cell RCC is the most common renal neoplasm (80% of all renal neoplasms) and represents about 2% of cancer deaths.32,33 It occurs primarily in the proximal tubule of the renal cortex. Other types include papillary (small fingerlike growths) and chromophobe RCC (larger cells), and both occur in the distal tubules of the kidneys.34 Confinement within the renal capsule, together with treatment, is associated with a better survival rate. The tumors usually occur unilaterally (Fig. 38.3). Renal transitional cell carcinoma (RTCC) is rare and primarily arises in the renal parenchyma and renal pelvis near the ureteral orifice. Renal adenomas (benign tumors) are uncommon but are increasing in number. The tumors are encapsulated and are usually located near the cortex of the kidney. Some tumors are unclassified because they have multiple cell types. Because the tumors can become malignant, they are usually surgically removed.

Renal cell carcinomas usually are spheroidal masses composed of yellow tissue mottled with hemorrhage, necrosis, and fibrosis. (From Damjanov I, Linder J, eds. Anderson’s pathology, 10th edition. St. Louis, MA: Mosby; 1996.)

Clinical Manifestations

The classic clinical manifestations of renal tumors are hematuria, dull and aching flank pain, palpable flank mass, and weight loss, but all these symptoms occur in fewer than 10% of cases. Further, they represent an advanced stage of disease, whereas earlier stages are often silent (painless hematuria). About 25% to 30% of individuals with RCC present with metastasis.35 The most common sites of distant metastasis are the lung, lymph nodes, liver, bone, thyroid gland, and central nervous system.

Evaluation and Treatment

Diagnosis is based on the clinical symptoms and imaging procedures. The tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) classification is used to stage RCC. Treatment for localized disease is surgical removal of the affected kidney (radical nephrectomy) or partial nephrectomy for smaller tumors, with combined use of chemotherapeutic agents. Radiofrequency ablation also may be used for early-stage tumors when surgery is not an option. Metastatic disease is treated with immunotherapy and targeted molecular therapies.36 Survival is related to tumor grade, tumor cell type, and extent of metastasis.

Bladder Tumors

Bladder tumors represent about 4.5% of all malignant tumors with 64,280 new cases each year and 12,260 deaths.32 The development of bladder cancer is most common in men older than 60 years. Risk factors include smoking, exposure to occupational chemicals, heavy consumption of phenacetin, uroepithelial schistosomiasis infection, or a genetic predisposition. Transitional cell (urothelial) carcinoma is the most common bladder malignancy, and tumors are usually superficial. More advanced tumors are muscle invasive. Less common forms are squamous cell and adenocarcinoma (cells that produce mucus).

Pathophysiology

Tumors present as flat or papillary and progress from in situ to invasive into the muscle and bladder wall (Fig. 38.4). Metastasis is usually to lymph nodes, liver, bones, or lungs. The TNM classification is used for staging bladder carcinoma. Secondary bladder cancer develops by invasion of cancer from bordering organs, such as cervical carcinoma in women or prostatic carcinoma in men.

(A) Papillary transitional cell carcinoma arising in the dome of the bladder as a cauliflower-like lesion (black arrow); location and frequency of bladder tumor types noted. (B) Bladder cancer with morphologic patterns of most common tumors. (A, From Stevens A, Lowe J, Scott I, eds. Core pathology, 3rd edition. London: Mosby; 2009; 2009. B, Adapted from Kissane JM, ed. Anderson’s pathology, 9th edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 1990.)

Top panel, A. A closeup of a cross-section of the dome of the bladder. The locations of tumors are as follow: 10 percent in the dome; 70 percent in the posterior and lateral wall; and 20 percent in trigone and bladder neck. Tumor types are 80 percent papillary and 3 percent carcinoma in situ. Bottom panel, B. The illustration on the top-left shows a flat tumor on the surface. The illustration on the top-right shows a flat invasive tumor, penetrating the layers. The illustration on the bottom-left shows a papilloma on the surface. The illustration on the bottom-right shows a papillary and invasive tumor, penetrating the layers.

Clinical Manifestations

Gross painless hematuria is the archetypal clinical manifestation of bladder cancer. Episodes of hematuria tend to recur, and they are often accompanied by bothersome LUT symptoms including daytime voiding frequency, nocturia, urgency, and urge urinary incontinence, particularly for carcinoma in situ. Flank pain may occur if tumor growth obstructs one or both ureterovesical junctions.

Evaluation and Treatment

Urine cytologic study (pathologic analysis of sloughed cells within the urine) is used for screening. Cystoscopy with tissue resection and biopsy is the first stage of treatment and confirms the diagnosis of bladder cancer. Use of biologic markers for bladder cancer diagnosis and treatment prognosis are available.37 Transurethral resection or laser ablation, combined with intravesical chemotherapy or immunotherapy, is effective for superficial tumors. Radical cystectomy (removal of the prostate and seminal vesicles in men and removal of the uterus, ovaries, and part of the vagina in women) with urinary diversion and adjuvant chemotherapy is required for locally invasive tumors.38

Urinary Tract Infection

Causes of Urinary Tract Infection

A UTI is an inflammation of the urinary epithelium (mucosa) usually caused by bacteria from gut flora. UTI can occur anywhere along the urinary tract, including the urethra, prostate, bladder, ureter, or kidney. At risk are premature newborns; prepubertal children; sexually active and pregnant women; women treated with antibiotics that disrupt vaginal flora; spermicide users; estrogen-deficient postmenopausal women; individuals with indwelling catheters; and individuals with diabetes mellitus, neurogenic bladder, or urinary tract obstruction. Cystitis is more common in women because of the shorter urethra and the closeness of the urethra to the anus (increasing the possibility of bacterial contamination). Adult women have a 50% to 60% lifetime incidence of UTI.39

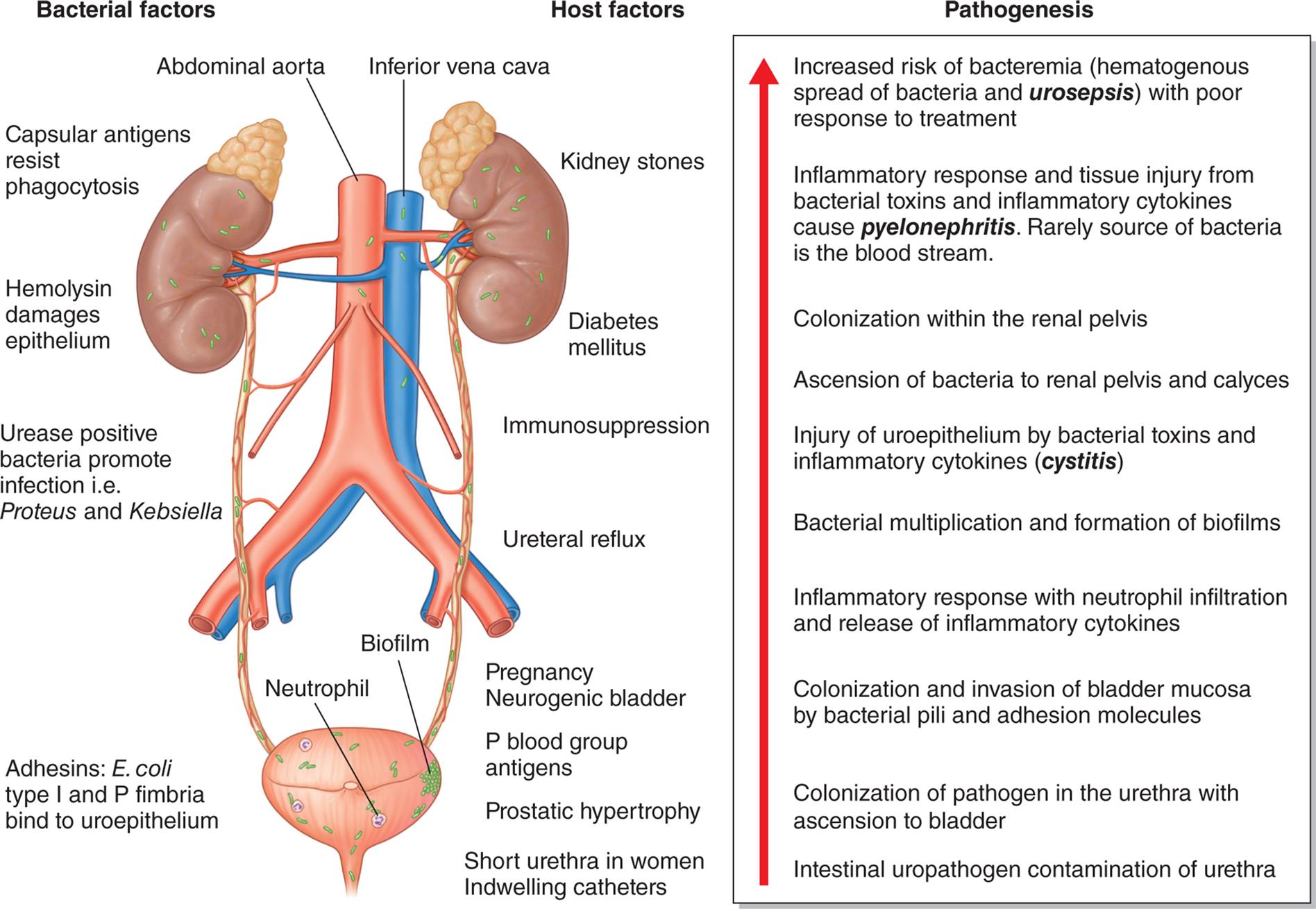

Several factors normally combine to protect against UTIs. Most bacteria are washed out of the urethra during micturition. The low pH and high osmolality of urea, the presence of Tamm-Horsfall protein or uromodulin (secreted by renal tubular cells in the distal loop of Henle), and secretions from the uroepithelium provide a bactericidal effect. The ureterovesical junction closes during bladder contraction, preventing reflux of urine to the ureters and kidneys. Both the longer urethra and the presence of prostatic secretions decrease the risk of infection in men. UTI occurs when a pathogen circumvents or overwhelms the body’s natural defense mechanisms and rapidly reproduces. Uncomplicated UTIs are mild with a self-limiting course and occur in individuals without any functional or anatomical anomalies in the urinary tract. A complicated UTI develops when there is an abnormality in the urinary system or a secondary disease, syndrome, or illness that compromises an individual’s defenses, such as diabetes mellitus, neurogenic bladder, urinary tract obstruction, renal transplant, or spinal cord injury.40 UTI may occur alone or in association with pyelonephritis, prostatitis, or nephrolithiasis. Up to 30% of cases of septic shock are caused by urosepsis (a systemic response to an infection in the urogenital tract that can include symptoms of shock).41 The mechanisms associated with UTI including bacterial and human factors are summarized in Fig. 38.5. Recurrent UTI is commonly defined as three or more UTIs within 12 months or two or more occurrences within 6 months. Recurrence is more common in women as compared to men. UTI may occur as a relapse when there is a second infection within the urinary tract caused by the same pathogen within 2 weeks of the original treatment or a reinfection that occurs more than 2 weeks after completion of treatment for the same or different pathogen.40 Guidelines are available for clinical management.42

An illustration shows the mechanisms of urinary tract infection. The illustration shows and labels the following structures on the urinary system: abdominal aorta, inferior vena cava, biofilm, and neutrophil. The bacterial factors include capsular antigens resist phagocytosis; hemolysin damages epithelium; urease positive bacteria promote infection, that is proteus and kebsiella; and adhesins: E coli type 1 and P fimbria bind to uroepithelium. The host factors include kidney stones; diabetes mellitus; immunosuppression; ureteral reflux; pregnancy neurogenic bladder; P blood group antigens; prostatic hypertrophy; and short urethra in women indwelling catheters. The pathogenesis, from the bottom to the top, is as follows. • Intestinal uropathogen contamination of urethra. • Colonization of urethra with ascension to bladder. • Colonization and invasion of bladder mucosa by bacterial pili and adhesion molecules. • Inflammatory response with neutrophil infiltration and release of inflammatory cytokines. • Bacterial multiplication and formation of biofilms. • Injury of uroepithelium by bacterial toxins and inflammatory cytokines (cystitis). • Ascension of bacteria to renal pelvis and calyces. • Colonization of renal pelvis. • Inflammatory response and tissue injury from bacterial toxins and inflammatory cytokines cause pyelonephritis. Rarely source of bacteria is the blood stream. • Increased risk of bacteremia (hematogenous spread of bacteria and urosepsis) with poor response to treatment.

Types of Urinary Tract Infection

Cystitis

Cystitis is an inflammation of the bladder, which is the most common site of UTI. The appearance of the bladder through a cystoscope describes the different types of cystitis:

- 1. Mild cystitis shows a hyperemic (red) mucosa.

- 2. Hemorrhagic cystitis shows diffuse mucosal hemorrhages and occurs with more advanced inflammation.

- 3. Suppurative cystitis shows mucosal pus formation or suppurative exudates.

- 4. Ulcerative cystitis results from prolonged infection with ulcers that may lead to sloughing of the mucosa.

- 5. Gangrenous cystitis is necrosis of the bladder wall and occurs with the most severe infections.

Pathophysiology

Two factors account for the development of UTI: the virulence of the pathogen and the efficiency of host defense mechanisms. The most common infecting microorganisms are uropathic strains of Escherichia coli, and the second most common is Staphylococcus saprophyticus. Less common microorganisms include Klebsiella, Proteus, Pseudomonas, fungi, viruses, parasites, or tubercular bacilli. Schistosomiasis is the most common parasitic invasion of the urinary tract on a global basis, particularly Africa and areas of the Middle East, and has a strong association with bladder cancer.43 Bacterial contamination of the normally sterile urine usually occurs by retrograde (backward) movement of gastrointestinal gram-negative bacilli into the urethra and bladder from the opening of the urethra. The microorganisms overcome normal defense mechanisms and can then move into the ureter and kidney. Uropathic strains of E. coli have type-1 fimbriae (also termed pili or fingerlike projections) that bind to receptors on the uroepithelium. Consequently, they resist flushing during normal micturition. They also can bind to latex catheters used for urinary drainage. Some women may be genetically susceptible to certain strains of E. coli attachment. In these cases, women have P blood group antigen (a glycolipid) that binds to P. fimbriae (pyelonephritis-associated fimbriae) of E. coli on the uroepithelium, allowing the pathogen to ascend the urinary tract. Infection initiates an inflammatory response and the symptoms of cystitis. The inflammatory edema in the bladder wall stimulates activation of stretch receptors. The activated stretch receptors initiate symptoms of bladder fullness with small volumes of urine, producing the urgency and frequency of urination associated with cystitis.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of cystitis are related to the inflammatory response and usually include polyuria, urinary frequency, urgency, dysuria (painful urination), and suprapubic and low back pain. Hematuria, cloudy or malodorous urine, flank pain, and mental status changes are more serious symptoms. Many individuals with bacteriuria are asymptomatic. Individuals with a complicated UTI may present with systemic symptoms such as fever, chills, mental status changes, tachycardia, hypotension, nausea, vomiting, pain, and incontinence. The elderly have the highest risk and may present with only confusion or vague abdominal discomfort.

Evaluation and Treatment

Cystitis in symptomatic individuals is diagnosed by urine culture of specific microorganisms with counts of 100,000/mL or more from freshly voided urine.44 The standard diagnostic test for UTI is urinalysis, which is both cost-effective and noninvasive. The most accurate way to obtain a urine specimen is a midstream clean catch. Positive nitrates and leukocyte esterase on the dipstick analysis are accurate indicators of UTI. Urinalysis screening of asymptomatic bacteriuria is only recommended in women during pregnancy and for individuals prior to undergoing invasive urologic procedures.45 Women reporting typical symptoms of uncomplicated lower UTI do not require any laboratory or diagnostic testing.46 Risk factors, such as urinary tract obstruction, should be identified and treated.

Evidence of bacteria from urine culture and antibiotic sensitivity warrants treatment with a microorganism-specific antibiotic. Optimal therapy depends on the severity and local bacterial resistance patterns. Acute uncomplicated cystitis in nonpregnant women can be diagnosed without an office visit or urine culture. If urine culture and sensitivity are ordered, the urine specimen must be obtained before the initiation of any antibiotic therapy; 3 to 7 days of treatment is most common.42

Complicated UTI requires 7 to 14 days of treatment. Relapsing infection within 7 to 10 days requires prolonged antibiotic treatment. Clinical symptoms are frequently relieved, but bacteriuria may still be present. Repeat cultures are not necessary as a test for cure post-treatment. For chronic infection with a continuation of symptoms, cultures should be obtained every 3 to 4 months until 1 year after treatment for evaluation and treatment of recurrent infection. Guidelines are available for the treatment of community-acquired UTIs, uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women, complicated cystitis, and for the prevention of catheter-associated cystitis.47

Painful Bladder Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis

Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) is defined as an unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure, discomfort) perceived to be related to the urinary bladder associated with LUT symptoms of more than 6 weeks’ duration in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes. It is most commonly diagnosed in women and in the fourth decade of life or after.

Pathophysiology. The cause of IC/BPS is unknown. IC/BPS can be conceptualized as a bladder pain disorder that is often associated with voiding and other systemic chronic disorders such as fibromyalgia, irritable bowel disease, chronic fatigue syndrome, Sjogren’s syndrome, chronic headaches, and vulvodynia.48 An autoimmune reaction may be responsible for the inflammatory response, which includes mast cell activation, altered uroepithelial permeability, and increased sensory nerve sensitivity. The inflammation is associated with a derangement of the glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder mucosa that makes it more susceptible to penetration by bacteria and noxious urinary solutes.Clinical Manifestations. Inflammation and fibrosis of the bladder wall (uroepithelium) are accompanied by pain. Bladder volume may decrease as a result of fibrosis. IC/BPS is also categorized by the presence or absence of hemorrhagic ulcers (Hunner ulcers or lesions). Absence of Hunner ulcers is a non-inflammatory phenotype with little evidence of bladder etiology and presents with somatic and/or psychological symptoms that commonly result in central nervous sensitization.49

Evaluation and Treatment. Diagnosis of IC/PBS requires a thorough history, physical examination and urinalysis, analysis of cystoscopy findings, the presence or absence of Hunner ulcers, and the exclusion of other diagnoses. The hallmark symptom of IC/PBS is pain, including sensations of pressure and discomfort located in the suprapubic area, urethra, vulva, vagina, rectum, lower abdomen, or back lasting longer than 6 weeks. Other characteristic symptoms of IC/PBS include bladder fullness, urinary urgency, frequency (including nocturia) with small urine volume, and chronic pelvic pain. No single treatment is effective. Treatment should focus on improving quality of life through self-care practices and behavioral modifications. Oral and intravesical therapies, sacral nerve stimulation, and intradetrusor botulinum toxin A are used for symptom relief. Fulguration with laser or electrocautery and/or injection with triamcinolone should be performed if Hunner ulcers are present. Surgery is used in refractory cases.50 Guidelines are available for the treatment of IC/BPS.51

Acute Pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis is an infection of one or both upper urinary tracts (ureter, renal pelvis, and kidney interstitium). Common causes are summarized in Table 38.4. Urinary obstruction and reflux of urine from the bladder (vesicoureteral reflux) are the most common underlying risk factors, with most cases occurring in women. One or both kidneys may be involved.

Table 38.4

Pathophysiology

Microorganisms usually associated with acute pyelonephritis include E. coli (most common), Proteus, or Pseudomonas. The latter two microorganisms are more commonly associated with infections after urethral instrumentation or urinary tract surgery. These microorganisms also split urea into ammonia, making an alkaline urine that increases the risk of stone formation. The infection is likely spread by ascending uropathic microorganisms along the ureters. Dissemination also may occur by way of the bloodstream. The inflammatory process primarily affects the pelvis, calyces, and medulla of the kidney. The infection causes infiltration of leukocytes with renal inflammation, renal edema, and purulent urine. In severe infections, localized abscesses may form in the medulla and extend to the cortex. The tubules are primarily affected, while the glomeruli are usually spared. Necrosis of renal papillae can develop. After the acute phase, healing occurs with fibrosis and atrophy of affected tubules. The number of bacteria decreases until the urine again becomes sterile. Acute pyelonephritis rarely causes renal failure.

Clinical Manifestations

The onset of symptoms is usually acute, with fever, chills, tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, and flank or groin pain. Symptoms characteristic of UTI, including frequency, dysuria, incontinence, and costovertebral tenderness, may precede systemic signs and symptoms.46 Older adults may have early nonspecific symptoms, such as low-grade fever, confusion, and malaise.

Evaluation and Treatment

Differentiating symptoms of cystitis from those of pyelonephritis by clinical assessment alone is difficult. The specific diagnosis is established by urine culture, urinalysis, and clinical manifestations. White blood cell casts formed in the renal tubules and flushed into the urine indicate pyelonephritis. However casts are not always present in the urine. A urine culture assay establishes a definitive diagnosis through identification of the uropathogen. A positive culture is characterized by bacteriuria of at least 105 CFU/mL.44 Individuals with complicated pyelonephritis may require blood cultures and diagnostic imaging if there is no response to antibiotic treatment or if there is a suspected obstruction. Optimal therapy for acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis depends on severity and local resistance patterns.52 Current guidelines recommend empiric therapy with a broad-spectrum antibiotic (e.g., fluoroquinolone) for patients with pyelonephritis, not requiring hospitalization. A urine specimen for culture and sensitivity must be collected prior to initiation of antibiotics.46 A post-treatment test of cure urinalysis or urine culture in asymptomatic individuals is not performed.42 However, follow-up urine cultures are obtained at 1 and 4 weeks after treatment if symptoms recur. Antibiotic-resistant microorganisms or reinfection may occur in cases of urinary tract obstruction or reflux. Intravenous pyelography and voiding cystourethrography are used to identify surgically correctable lesions.

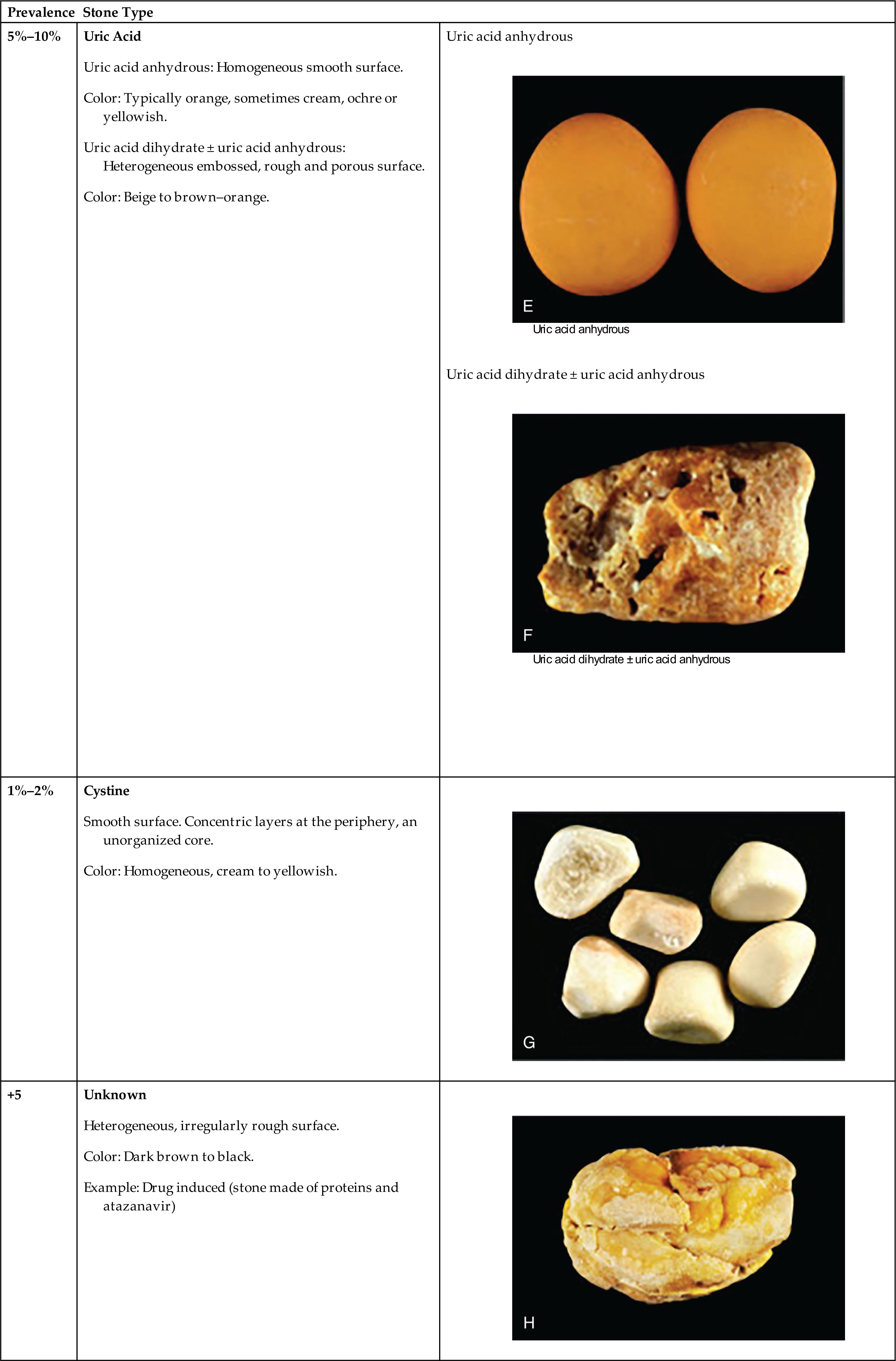

Chronic Pyelonephritis

Chronic pyelonephritis is a persistent or recurrent infection of one or both of the kidneys leading to scarring. The specific cause of chronic pyelonephritis may be unknown (idiopathic) or associated with chronic UTIs, vesicoureteral reflux, or kidney stone obstructive uropathy. Other causes include drug toxicity from analgesics, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), ischemia, irradiation, and immune-complex diseases.

Pathophysiology

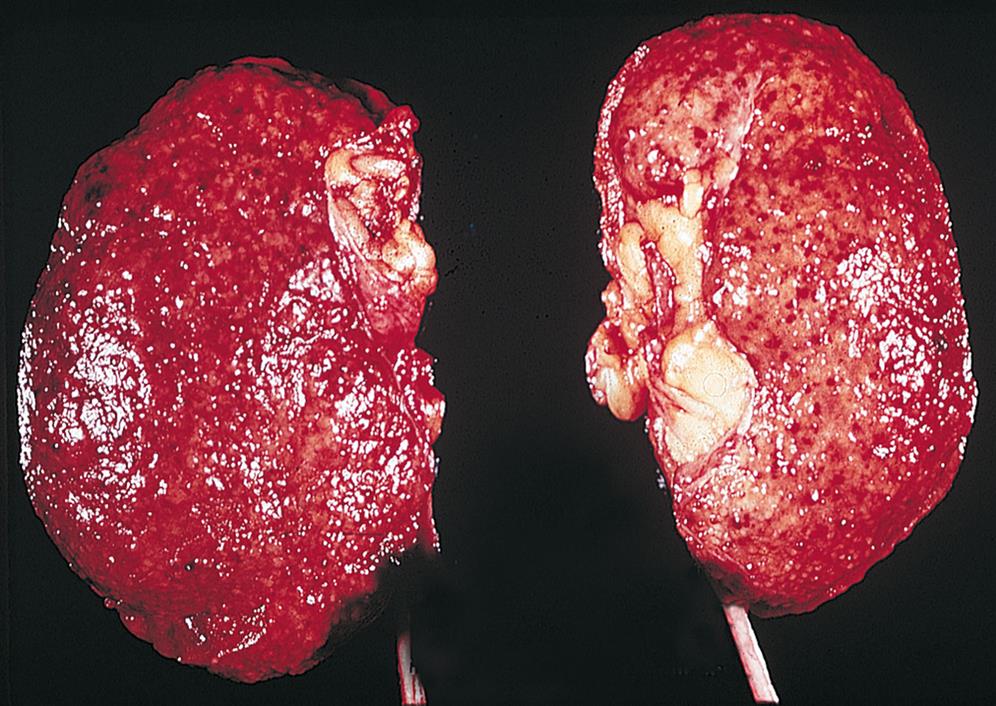

Chronic urinary tract obstruction prevents elimination of bacteria and starts a process of progressive inflammation. Alterations occur within the renal pelvis and calyces from the obstruction and inflammation (Fig. 38.6). There is destruction of the tubules and diffuse scarring, which impairs urine-concentrating ability. The lesions of chronic pyelonephritis are sometimes termed chronic interstitial nephritis because the inflammation and fibrosis are located in the interstitial spaces between the tubules.

(Right) Small, shrunken, irregularly scarred kidney of an individual with chronic pyelonephritis. (Left) Kidney is of normal size but also shows scarring on the upper pole. From Damjanov I. Pathology for the health professions, 4th edition. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012.

Clinical Manifestations

The early symptoms of chronic pyelonephritis are often minimal and may include urinary frequency, dysuria, flank pain, and hypertension. Progression can lead to kidney failure, particularly in the presence of other risk factors (e.g., obstructive uropathy or diabetes mellitus). There is an inability to conserve sodium with loss of tubular function and development of hyperkalemia and metabolic acidosis. Risk for dehydration must be considered if there is loss of the ability to concentrate the urine.

Evaluation and Treatment

Urinalysis, intravenous pyelography, and ultrasound are used as diagnostic tests to evaluate chronic pyelonephritis. Treatment is related to the underlying cause. Obstruction must be relieved. Antibiotics may be given, with prolonged antibiotic therapy for recurrent infection.

Glomerular Disorders

Glomerulonephritis

Acute glomerulonephritis is an inflammation isolated to the kidney glomerulus caused by primary glomerular injury, including infection, immunologic responses, ischemia, free radicals, drugs, toxins, and vascular disorders. Secondary glomerular injury is a glomerular injury that occurs as a consequence of systemic diseases, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, bacterial toxins, systemic lupus erythematosus, congestive heart failure, and HIV-related kidney disease.

Pathophysiology

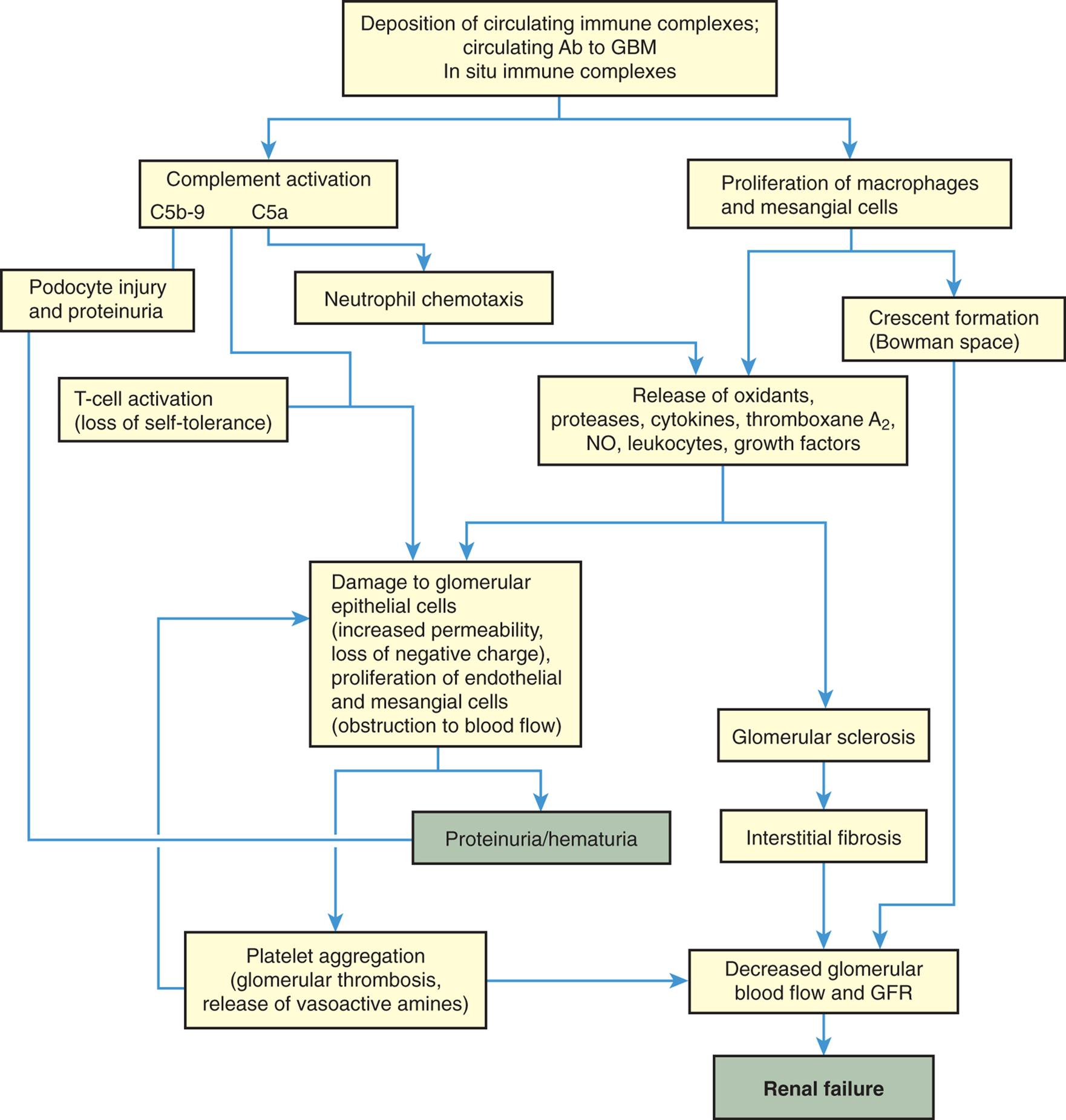

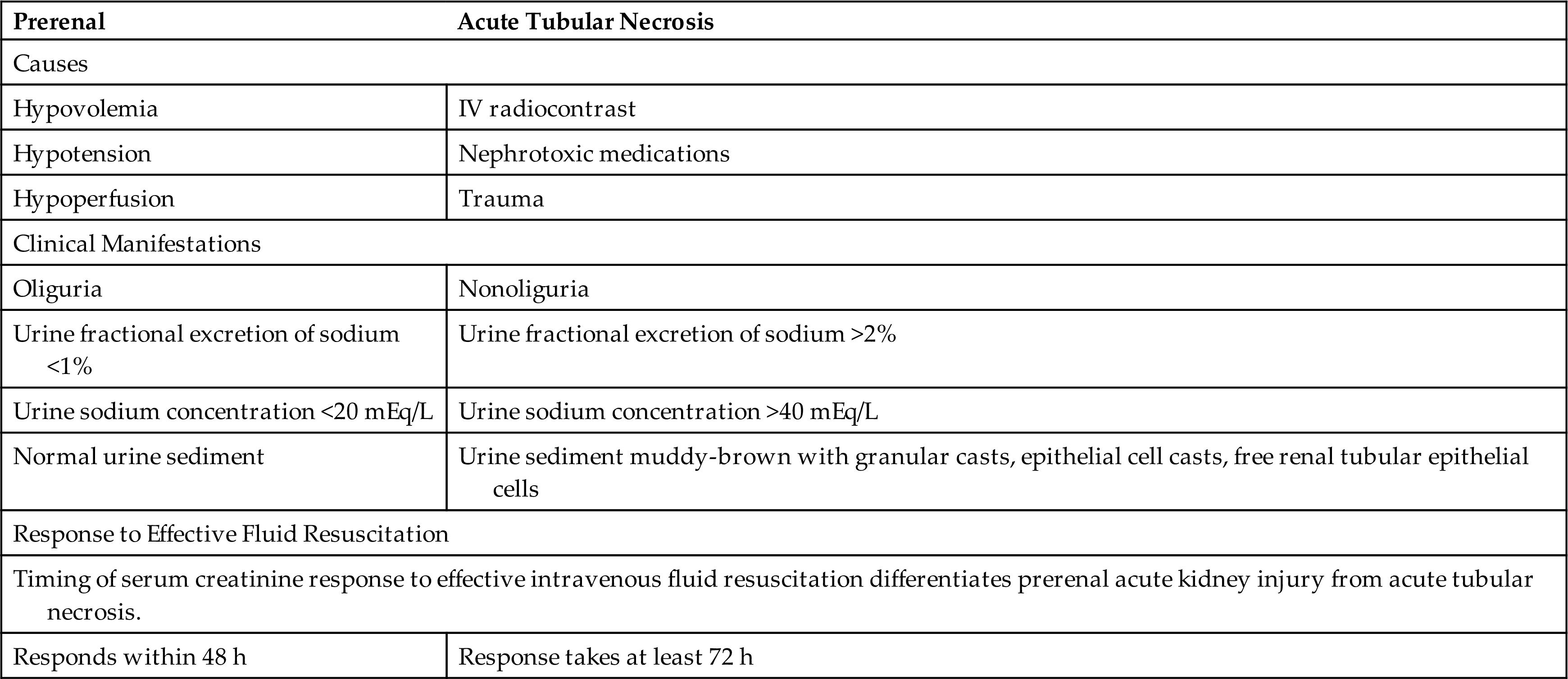

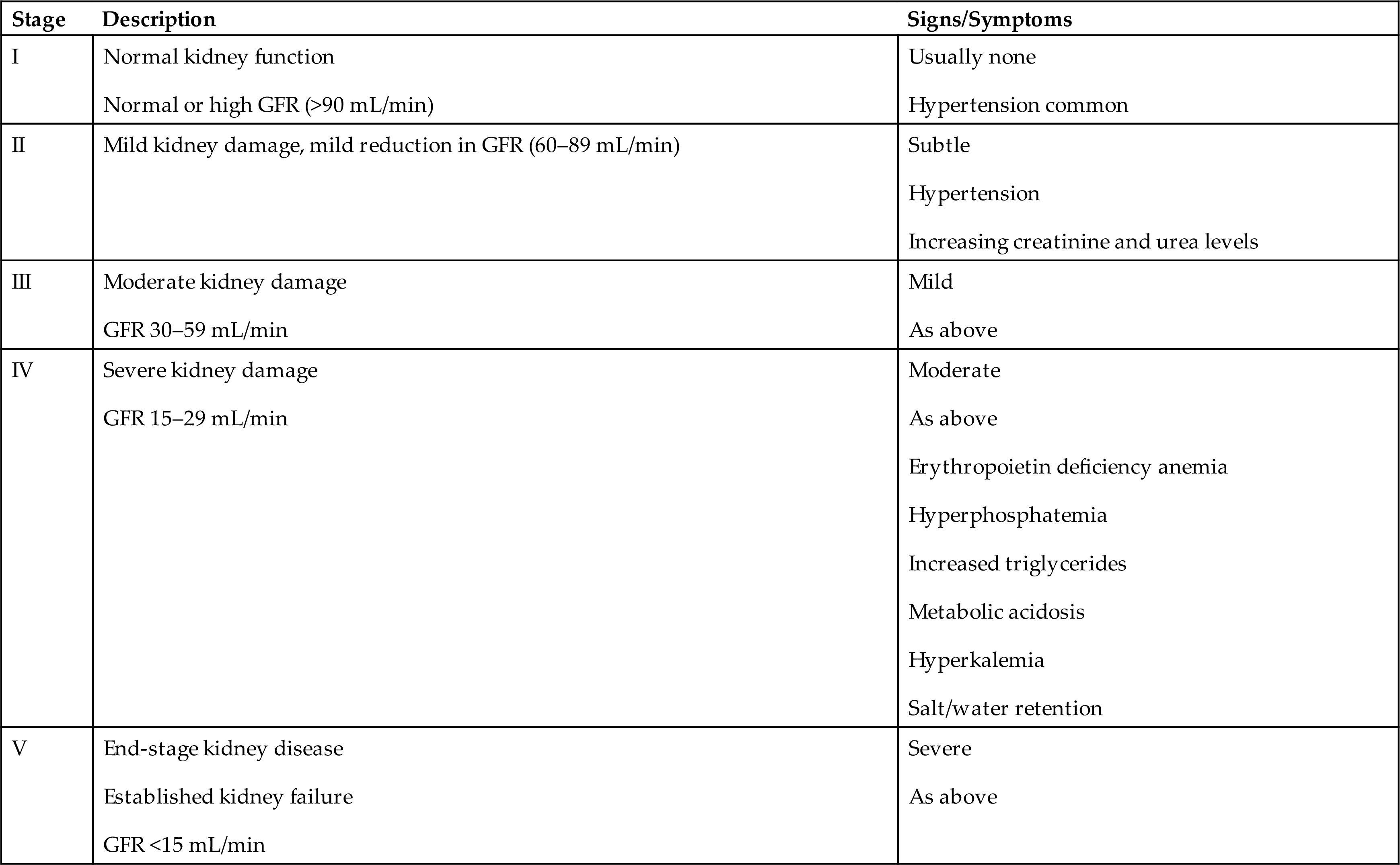

Immune mechanisms are a major component of both primary and secondary glomerular injury. (Fig. 38.7). The injury damages the glomerular capillary filtration membrane. The most common type of immune injury is related to the presence of antigen-antibody complexes within the glomerulus (Table 38.5). Nonimmune glomerular injury is related to injury or ischemia from metabolic disorders, toxin exposure, drugs, vascular disorders, and infection. Different causes of injury may result in more than one type of glomerular lesion; thus, lesions are not necessarily disease specific (Table 38.6).

Ab, Antibody; GBM, glomerular basement membrane; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; NO, nitric oxide.

A flowchart shows the mechanisms of glomerular injury. 1. Deposition of circulating immune complexes; circulating Ab to G B M; and In situ immune complexes. Leads to 2 and 3. 2. Complement activation (C 5 b-9 and C 5 a). Leads to 4, 5, 7, and 9. 3. Proliferation of macrophages and mesangial cells. Leads to 6 and 8. 4. Podocyte injury and proteinuria. Leads to 11. 5. Neutrophil chemotaxis. Leads to 8. 6. Crescent formation (Bowman space). Leads to 14. 7. T-cell activation (loss of self-tolerance). Leads to 9. 8. Release of oxidants, proteases, cytokines, thromboxane A sub 2, N O, leukocytes, growth factors. Leads to 9 and 10. 9. Damage to glomerular epithelial cells (increased permeability, loss of negative charge), proliferation of endothelial and mesangial cells (obstruction to blood flow). Leads to 11 and 13. 10. Glomerular sclerosis. Leads to 12. 11. Proteinuria/hematuria. 12. Interstitial fibrosis. Leads to 14. 13. Platelet aggregation (glomerular thrombosis, release of vasoactive amines). Leads to 9 and 14. 14. Decreased glomerular blood flow and G F R. Leads to 15. 15. Renal failure.

Table 38.5

Data from Foster MH. Basement membranes and autoimmune diseases. Matrix Biology, 2017;57–58:149–168; Nester CM, Smith RJ. Complement inhibition in C3 glomerulopathy. Seminars in Immunology, 2016;28(3):241–249; Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Batsford S. Pathogenesis of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis a century after Clemens von Pirquet. Kidney International, 2007;71(11):1094–1104.

Table 38.6

| Lesion | Distribution When Single Glomeruli Considered |

|---|---|

| Global | A lesion involving the entire glomerulus |

| Segmental-local | Changes in one part of the glomerulus with other parts unaffected |

Immune injury is caused by activation of the inflammatory response (i.e., complement activation, leukocyte recruitment, and release of cytokines from leukocytes). Injury begins after the antigen-antibody complexes have deposited or formed in the glomerular capillary wall or mesangium. Complement is deposited with the antibodies and complement activation can cause cell injury or serve as a chemotactic stimulus for attraction of leukocytes (neutrophils, monocytes, and T lymphocytes). These phagocytes, along with activated platelets, further the inflammatory reaction by releasing mediators that injure the glomerular filtration membrane including epithelial cells, glomerular basement membrane, and endothelial cells (podocytes and filtration slits).53 The injury increases glomerular filtration membrane permeability and reduces glomerular membrane surface area.

There may be hypertrophy and proliferation of mesangial cells and expansion of the extracellular matrix in the Bowman space. The deposition of these substances and cell proliferation forms a crescent shape within the Bowman space that can be seen under a microscope and can assist with diagnosis if a biopsy is performed. The result of these processes is compression of glomerular capillaries, decreased glomerular blood flow, hypoxic injury, decreased driving glomerular hydrostatic pressure, alteration in the filtration membrane, and decreased GFR. Crescent formation is associated with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.54

Loss of the normal negative electrical charge across the glomerular filtration membrane and increase in filtration pore size enhance movement of proteins into the urine. Proteins are normally repelled because they also have a negative charge and thus are not filtered into the urine. Red blood cells also escape if pore size is large enough. Consequently, proteinuria and/or hematuria develop. The severity of glomerular damage and decline in glomerular function is related to the size, number, and location (i.e., focal [affecting some glomeruli] or diffuse [affecting glomeruli throughout the kidney]) of cells injured; duration of exposure; and type of antigen-antibody complexes formed.

Clinical Manifestations

The onset of glomerulonephritis may be sudden or insidious. A significant loss of nephron function can occur before symptoms develop. Acute glomerulonephritis may be silent, mild, moderate, or severe in symptom presentation. Severe or progressive glomerular disease causes oliguria (urine output of 30 mL/h or less), hypertension, and renal failure. Focal lesions tend to produce less severe clinical symptoms. Salt and water are reabsorbed, contributing to fluid volume expansion, edema, and hypertension.

Two distinct symptoms of more severe or rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis are (1) hematuria with red blood cell casts (the red blood cells accumulate in the kidney tubules and are washed into the urine in the form of a cast of the tubule) and (2) proteinuria exceeding 3 to 5 g/day with albumin (macroalbuminuria). Glomerular bleeding provides prolonged contact with the acidic urine and transforms hemoglobin to methemoglobin, which has a brownish color and no blood clots.

Evaluation and Treatment

The diagnosis of glomerular disease is confirmed by the progressive development of clinical manifestations and abnormal laboratory findings. Common urinalysis findings associated with glomerular disease include proteinuria, red blood cells, white blood cells, and casts. Reduced GFR during glomerulonephritis is evidenced by elevated plasma urea, cystatin C, and creatinine concentrations, or by reduced renal creatinine clearance (see Chapter 37). Microscopic evaluation from renal biopsy can provide a specific determination of renal injury and the type of pathologic lesion (i.e., the formation of glomerular crescents as previously described and location and character of glomerular lesions). Patterns of antigen-antibody complex deposition within the glomerular capillary filtration membrane have been established using light, electron, and immunofluorescent microscopy. Electron microscopy differentiates morphologic changes within the glomerular capillary wall (e.g., subendothelial and mesangial electron-dense deposits, increased mesangial matrix, mesangialization of capillary loops, and foot process fusion). Staining with fluorescein identifies complement and different antibodies (i.e., immunoglobulin G [IgG] or immunoglobulin A [IgA]) and associated configurations when viewed under ultraviolet light with light microscopy. Findings with microscopy provide information about the distribution and lesions of immune response injury and guide therapy.55

Reduced GFR during glomerulonephritis is evidenced by elevated plasma urea, cystatin C, and creatinine concentrations, or by reduced creatinine clearance (see Tests of Renal Function in Chapter 37). Edema, caused by excessive sodium and water retention and or loss of plasma proteins (see Chapter 3 for the pathophysiology of edema), may require the use of diuretics or dialysis.

Management principles for treating glomerulonephritis are related to treating the primary cause, preventing or minimizing immune responses, and correcting accompanying problems. Accompanying problems include edema, hypertension, hypoalbuminemia, and hyperlipidemia. Specific treatment regimens are necessary for particular types of glomerulonephritis. Antibiotic therapy is essential for the management of underlying infections that may be contributing to ongoing antigen-antibody responses. Corticosteroids decrease antibody synthesis and suppress inflammatory responses. Cytotoxic agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide) may be used to suppress the immune response in corticosteroid-resistant cases. Anticoagulants may be useful for controlling fibrin crescent formation in rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

Types of Glomerulonephritis

The types of glomerulonephritis can be described according to cause, pathologic lesions determined by biopsy (Table 38.7), disease progression (acute, rapidly progressive, chronic), or clinical presentation (nephrotic syndrome, nephritic syndrome, acute or chronic renal failure). In nearly all types of glomerulonephritis, the epithelial or podocyte layer of the glomerular capillary membrane is disturbed with loss of negative charges and changes in membrane permeability. Plasma proteins (albumin) and red blood cells can escape into the urine and can cause proteinuria and/or hematuria. The mesangial matrix may be expanded, or the basement membrane thickened decreasing blood flow through the glomerular capillaries and decreasing GFR. Many types of glomerular injury occur most often in children or young adults, including acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis and minimal change nephropathy (lipoid nephrosis). Details of these diseases are presented in Chapter 39.

Table 38.7

Complications of systemic diseases, such as diabetic nephropathy and systemic lupus erythematosus, can affect the entire nephron with significant glomerular injury. Different patterns of injury develop over the course of these diseases, and there is usually chronic progression. They are described in the next section.

Chronic Glomerulonephritis

Chronic glomerulonephritis encompasses several glomerular diseases with a progressive course leading to chronic kidney failure. There may be no history of kidney disease before the diagnosis. Hypercholesterolemia and proteinuria have been associated with progressive glomerular and tubular injury (Fig. 38.8). The proposed mechanism is related to those observed in glomerulosclerosis and interstitial injury, such as inflammatory processes and glomerular hyperfiltration. The primary cause may be difficult to establish because advanced pathologic changes may obscure specific disease characteristics. Diabetes nephropathy and lupus nephritis are examples of secondary causes of chronic glomerular injury. Renal insufficiency usually begins to develop after 10 to 20 years of disease, followed by nephrotic syndrome (see next section) and an accelerated progression to end-stage renal failure (ESRF). Symptom patterns vary depending on the underlying cause and the areas of the kidney that are damaged. The specific pathologic changes are identified by renal biopsy, which is best performed in the early stages of CKD to identify specific treatment options. Management of the underlying disease and use of steroids, immunosuppressive agents, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAAS) inhibitors, and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) can prolong remissions and preserve renal function (see Emerging Science Box: Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System Inhibitors in Patients With COVID-19). Dialysis or kidney transplantation ultimately may be needed.

The kidneys appear small, are uniformly shrunken, and have a finely granular external surface. (From Damjanov I. Pathology for the health professions, 4th edition. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2012.)

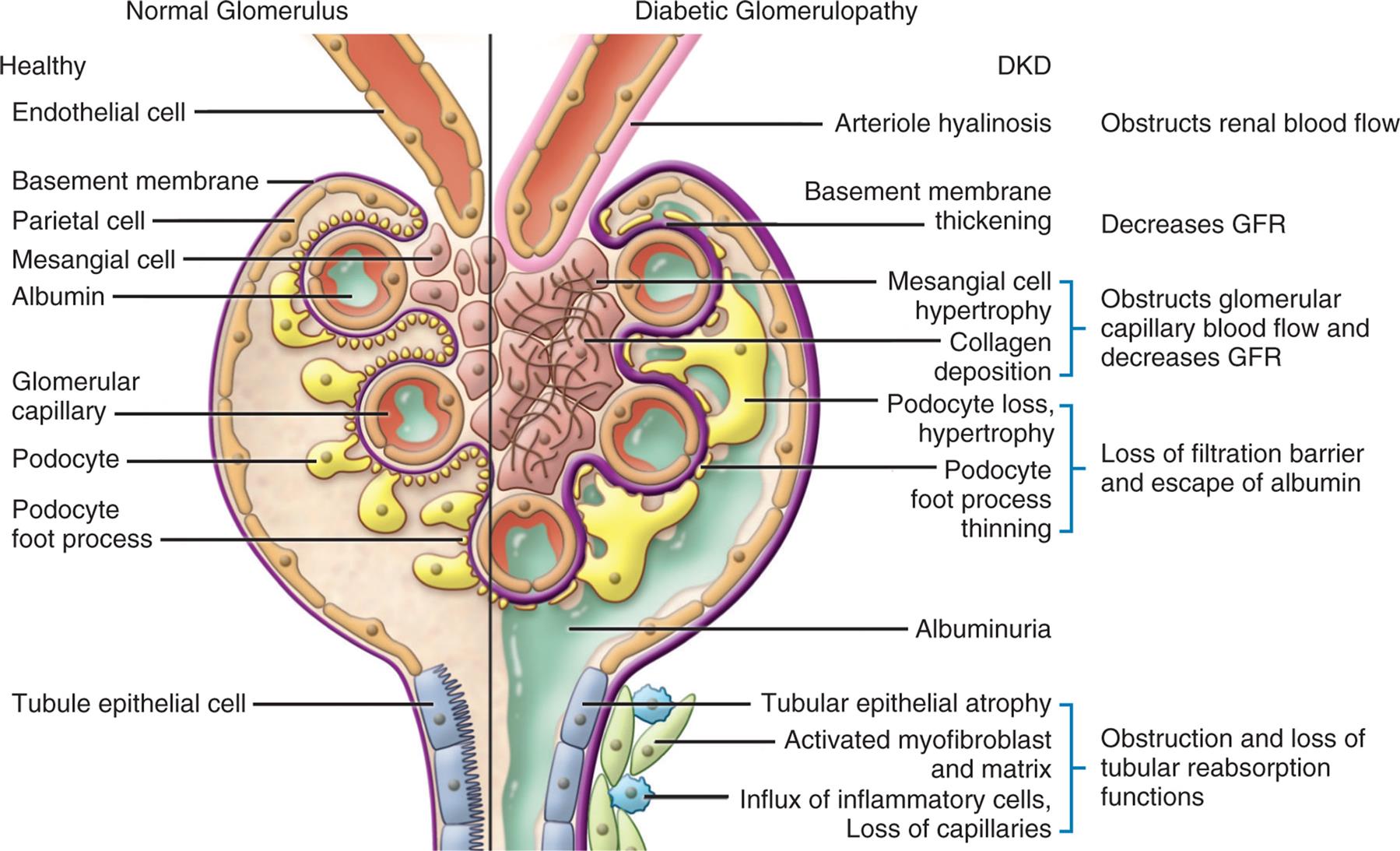

Diabetic nephropathy develops from metabolic (accumulation of advanced glycosylated end products), inflammatory (transforming growth factor-beta and protein kinase C), and macrovascular and microvascular complications related to chronic hyperglycemia (see Chapter 22). Changes in the glomerulus are characterized by podocyte injury, progressive thickening and fibrosis of the glomerular basement membrane, expansion of the mesangial matrix (diffuse diabetic glomerulosclerosis), and nodular glomerulosclerosis (Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules; see Fig. 38.9) with albuminuria, loss of tubular cells, and progression to chronic kidney disease. Although albuminuria is the classic phenotype of progressive diabetic renal disease, two new phenotypes have emerged (i.e., “nonalbuminuric renal impairment” and “progressive renal decline”), suggesting there can be progressive failure of renal function (i.e., declining GFR) without albuminuria. These “new” phenotypes may be the consequence of improved treatment. Work is in progress to determine if diagnostic and treatment guidelines should be modified for the management of these different phenotypes.56 Diabetic nephropathy is the most common cause of CKD and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) for both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.57 ESRD requires treatment with dialysis or renal transplantation.58

An illustration of the cross-section of the glomerulus compares the structures of normal glomerulus and diabetic glomerulopathy. Normal glomerulus: healthy endothelial cell, basement membrane, parietal cell, mesangial cell, albumin, glomerular capillary, podocyte foot process, and tubule epithelial cell. Diabetic glomerulopathy: D K D, obstructs renal blood flow (arteriole hyalinosis), decreases G F R (basement membrane thickening), obstructs glomerular capillary blood flow and decreases G F R (mesangial cell hypertrophy, collagen deposition), loss of filtration barrier and escape of albumin (podocyte loss, hypertrophy, podocyte foot process thinning), albuminuria, and obstruction and loss of tubular reabsorption functions (tubular epithelial atrophy, activated myofibroblast and matrix, and influx of inflammatory cells, loss of capillaries).

Lupus nephritis is an inflammatory complication of the chronic autoimmune syndrome systemic lupus erythematosus (see Chapter 9). The renal component of the disease may be caused by the formation of autoantibodies against double-stranded DNA and nucleosomes with glomerular deposition of the immune complexes. Immune complexes also may be formed in situ by binding to planted antigens of circulating autoantibodies. There is complement activation and a cascade of inflammatory events resulting in damage to the glomerular membrane with mesangial expansion (see Chapter 8).59 Various glomerular lesion patterns are identifiable on biopsy, including membranous, mesangial, membranoproliferative, and diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis; tubular fibrosis can also be present (Table 38.8). Symptom presentation is variable depending on lesion involvement and can include proteinuria, microscopic hematuria, edema, and other signs of nephrotic syndrome. Disease progression may be silent or may progress to ESRD over a period of years. Treatment includes the use of immunosuppressive agents and efforts to protect the kidney from secondary nonimmune consequences of acute injury.60

Table 38.8

| Type and Cause | Histopathophysiology |

|---|---|

| Associated with Nephritic Syndrome | |

| Acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis (PIGN) (e.g., group A beta-hemolytic streptococci [more common in children]; staphylococcus [more common in older adults]) | Subepithelial deposits of IgG and complement complexes; infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes; proliferation of mesangial and epithelial cells with occlusion of glomerular capillary blood flow and decreased glomerular filtration; usually diffuse lesions |

| Rapidly progressive or crescentic glomerulonephritis (a clinical syndrome): Type I: Formation of IgG antibodies against pulmonary capillary and glomerular basement membrane (Goodpasture syndrome); activation of complement and neutrophils; more common in young men; causes pulmonary hemorrhage and renal failure Type II: Mesangial immune-complex deposition (PIGN, SLE, IgA nephropathy) Type III: Pauci-immune, lack of antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies antibodies or immune complexes; presence of serum antineutrophil cytoplasmic (ANC) antibodies associated with systemic vasculitides (usually idiopathic); nonspecific response to glomerular injury; can occur in any severe glomerular disease | Accumulation of fibrin, macrophages, and epithelial cell proliferation into the Bowman space forms crescents and occludes glomerular capillary blood flow, decreasing glomerular filtration; antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies lead to necrotizing, proliferative glomerulonephritis, and renal failure; diffuse lesions |

| Deposits of immune complexes in the mesangium with mesangial cell proliferation; results in decreased glomerular blood flow and glomerular filtration; leads to hematuria/proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome | |

| Associated with Nephrotic Syndrome | |

Minimal change nephropathy (lipoid nephrosis) Glomerular basement membrane appears normal Most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in children (see Chapter 39) |

Glomeruli look normal under light microscopy; electron microscopy reveals uniform diffuse effacement of epithelial (podocyte) foot processes; loss of negative charge in basement membrane and increased permeability lead to severe proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome |

| Focal proliferation of endothelial and mesangial cells and glomerulosclerosis from hyaline deposits in segmental parts of the glomerular membrane; there is effacement (thinning or deletion) of epithelial podocytes, with a significant increase in pore size resulting in proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome; can progress to involve entire glomerulus and development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis | |

| Diffuse thickening of glomerular basement membrane and capillary wall from deposits of antibody, complement, and release of inflammatory cytokines; increased permeability with proteinuria and leading cause of nephrotic syndrome in white adults | |

| Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) | Mesangial cell proliferation; thickening of basement membrane; subendothelial deposits of immune-complex occlude glomerular capillary blood flow and decrease glomerular filtration; diffuse lesions |

| Usually idiopathic; associated with hypocomplementemia Type I: Activation of classical complement pathway with nephrotic syndrome (hepatitides B and C, SLE) Type II: Activation of alternate complement pathway with hematuria (idiopathic); no circulating immune complexes Type III: Activation of alternative complement pathway with nephrotic syndrome; can be familial | |

IgA Nephropathy (Berger Disease) Usually idiopathic (can be associated with cirrhosis and minimal change disease); elevated IgA plasma levels (also see Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis in Chapter 39) |

Mesangial proliferation with deposition of IgA; release of inflammatory mediators with cellular proliferation; crescent formation, glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, decreased GFR and hematuria; usually focal, some diffuse lesions |

GBM, Glomerular basement membrane; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Nephrotic and Nephritic Syndromes

Nephrotic and nephritic syndromes are consequences of glomerular injury and present with a pattern of clinical manifestations. Nephrotic syndrome is the excretion of 3.5 g or more of protein in the urine per day. It occurs when glomerular filtration of plasma proteins, particularly albumin, exceeds tubular reabsorption. Primary causes of nephrotic syndrome include particular types of glomerular injury including minimal change nephropathy (lipoid nephrosis) (see Chapter 39), membranous glomerulonephritis, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (see Table 38.8. Secondary forms of nephrotic syndrome occur in systemic diseases, including diabetes mellitus (see Chapter 22), amyloidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus (see Chapter 9), and IgA vasculitis (Henoch–Schönlein purpura) (see Chapter 39). Nephrotic syndrome is also associated with certain medications (e.g., NSAIDs), infections, malignancies, and vascular disorders. Familial or inherited forms of nephrotic syndrome result from genetic defects that affect the function and composition of the glomerular capillary wall (i.e., alterations in basement membrane type IV collagen [Alport syndrome] and podocyte dysfunction resulting in steroid resistance).61 It often signifies a more serious prognosis when present as a secondary complication. Nephrotic syndrome is more common in children (see Chapter 39) than in adults and is more commonly idiopathic in adults.

Nephritic syndrome is characterized by hematuria and red blood cell casts in the urine. Hypertension, edema, and oliguria also are components of the syndrome. Proteinuria is present but is usually less severe than in nephrotic syndrome. It occurs primarily with infection-related glomerulonephritis (e.g., hepatitis B and C and acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis), rapidly progressive crescentic glomerulonephritis, antiphospholipid syndrome (production of antiphospholipid antibodies that cause thrombotic microangiopathy), and lupus nephritis.59

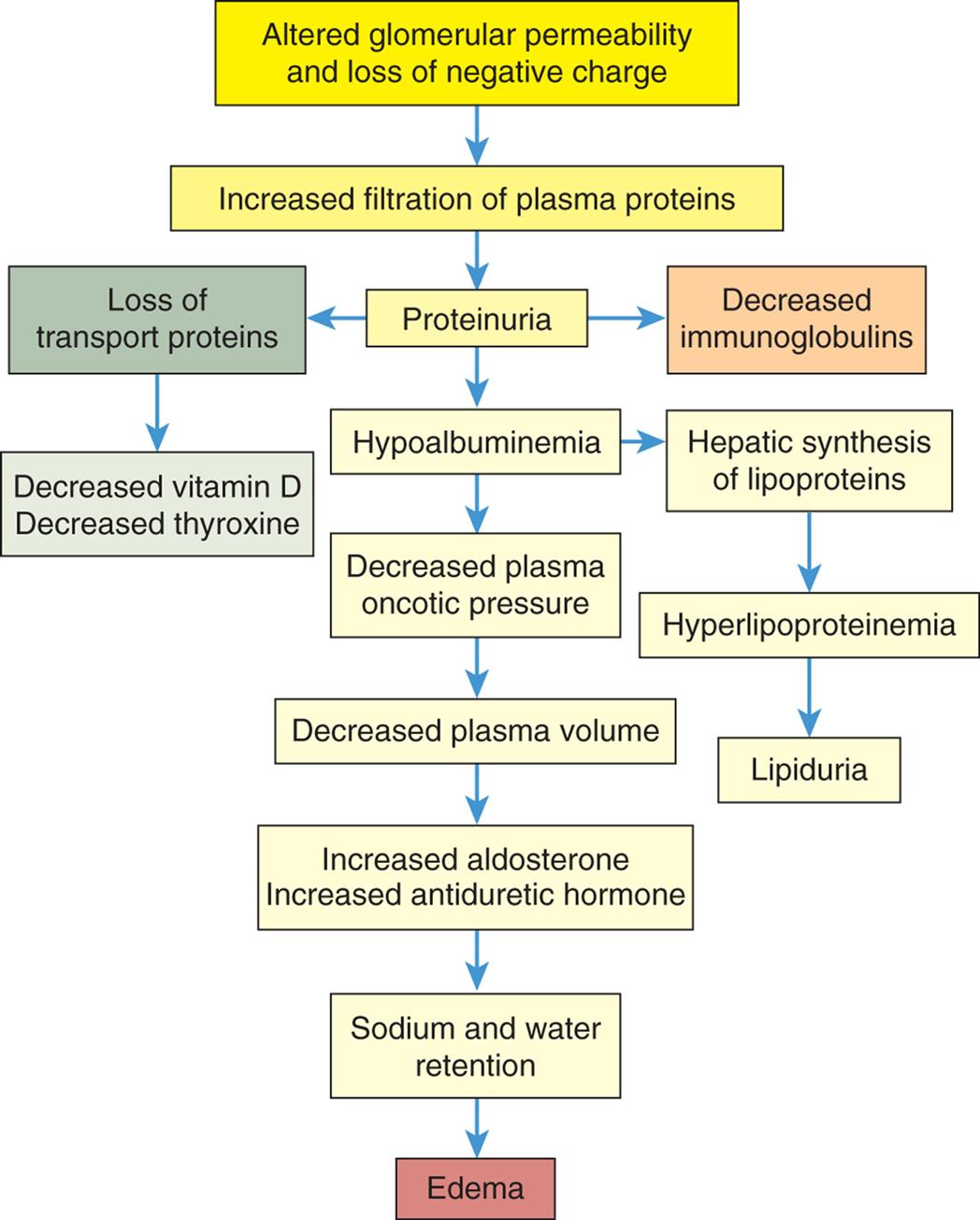

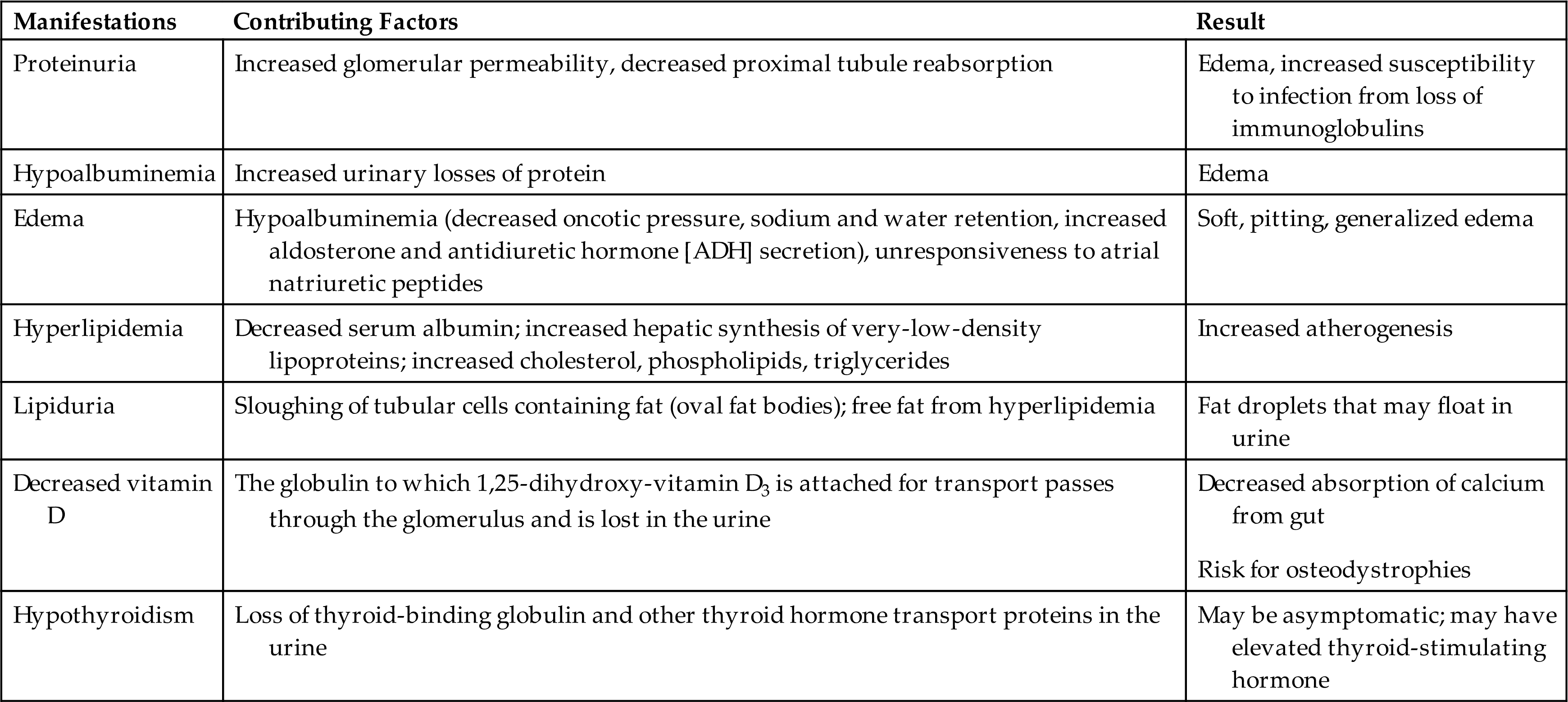

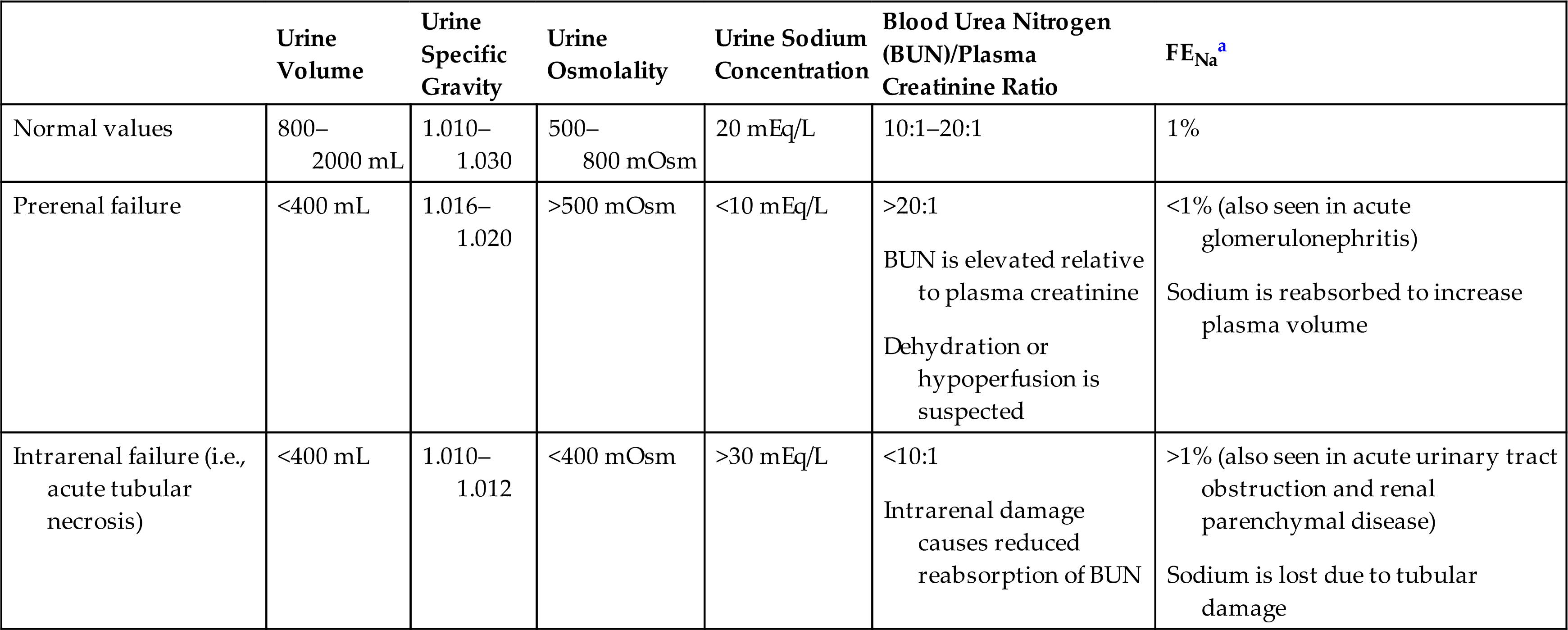

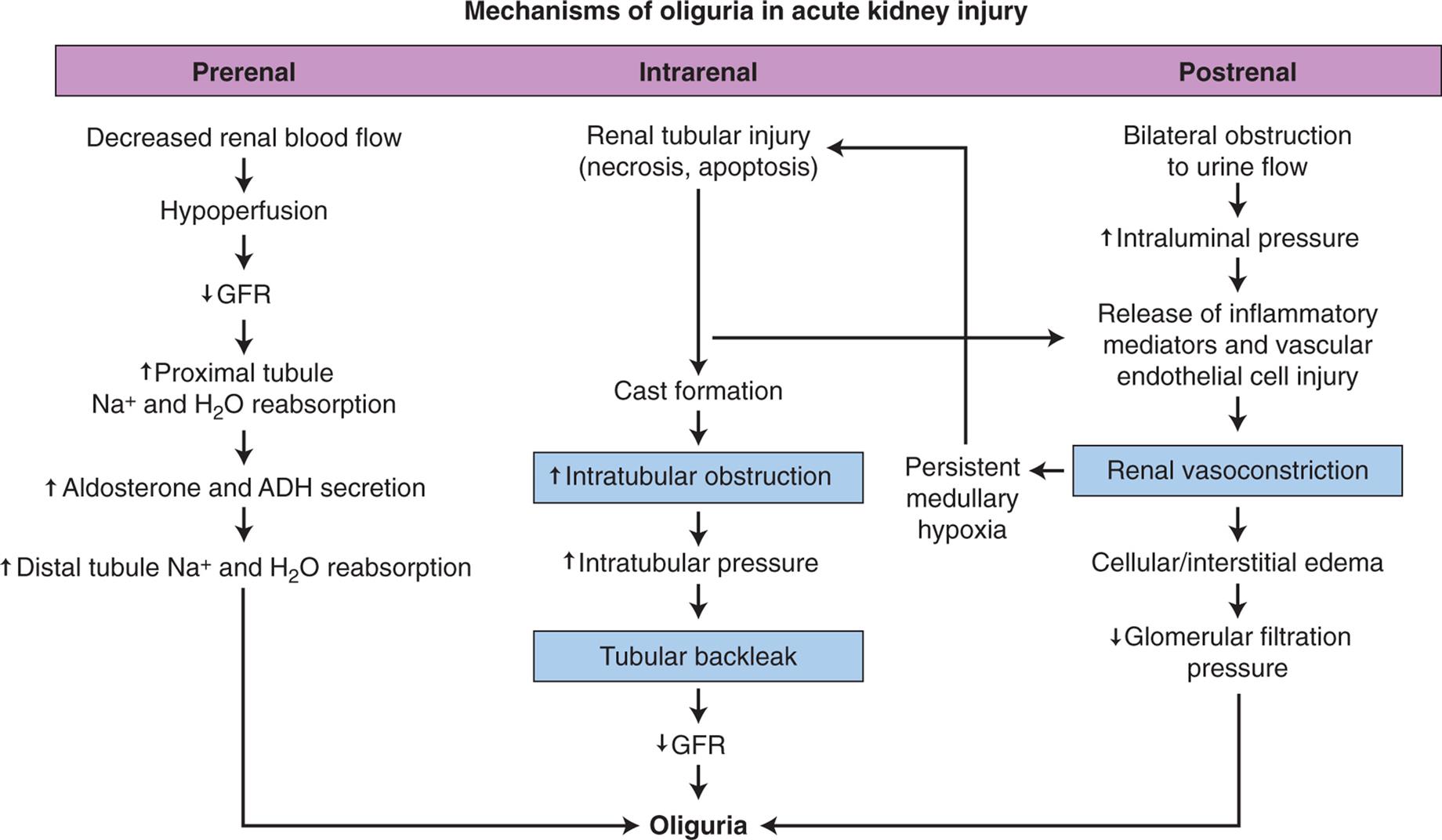

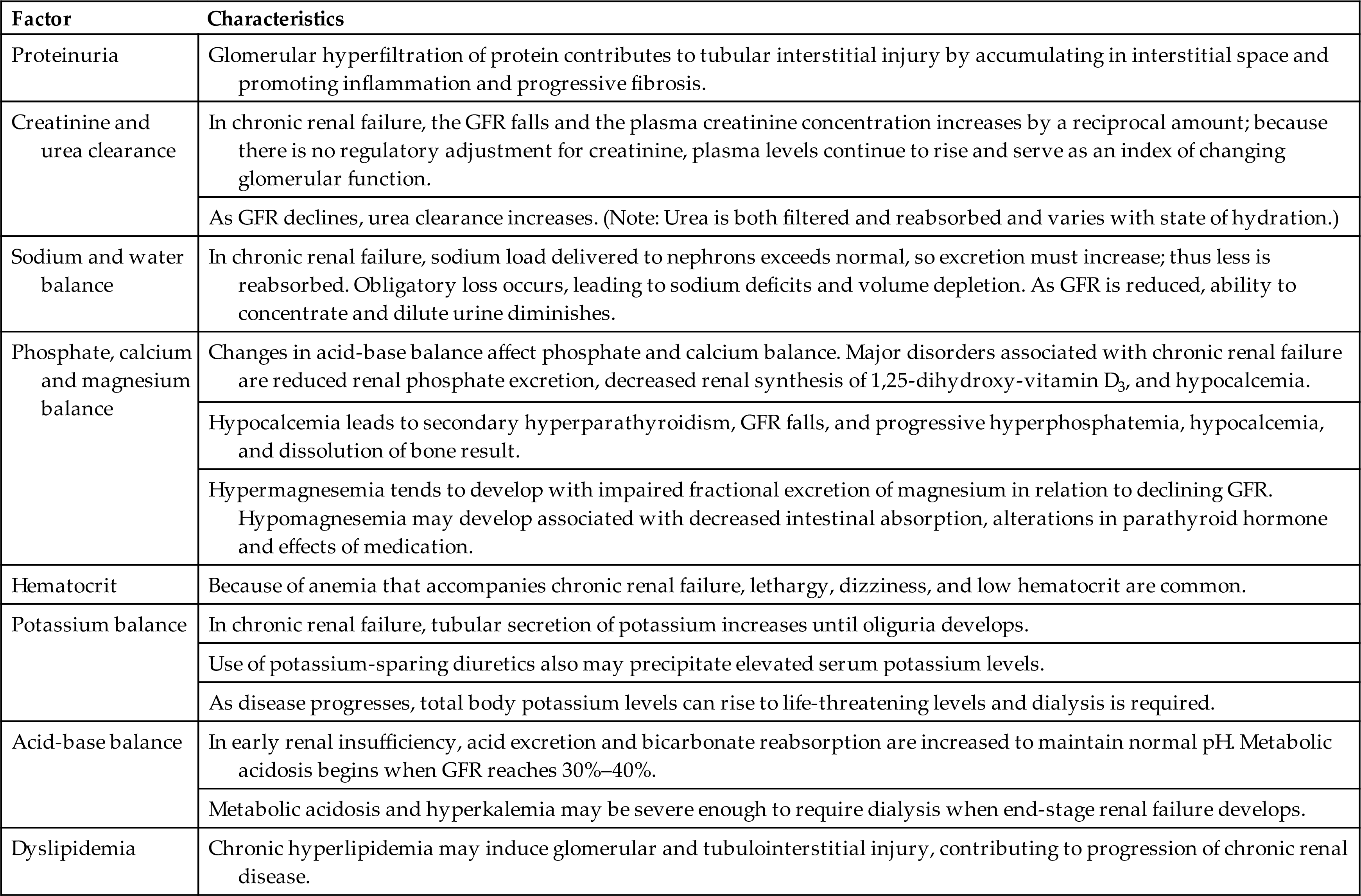

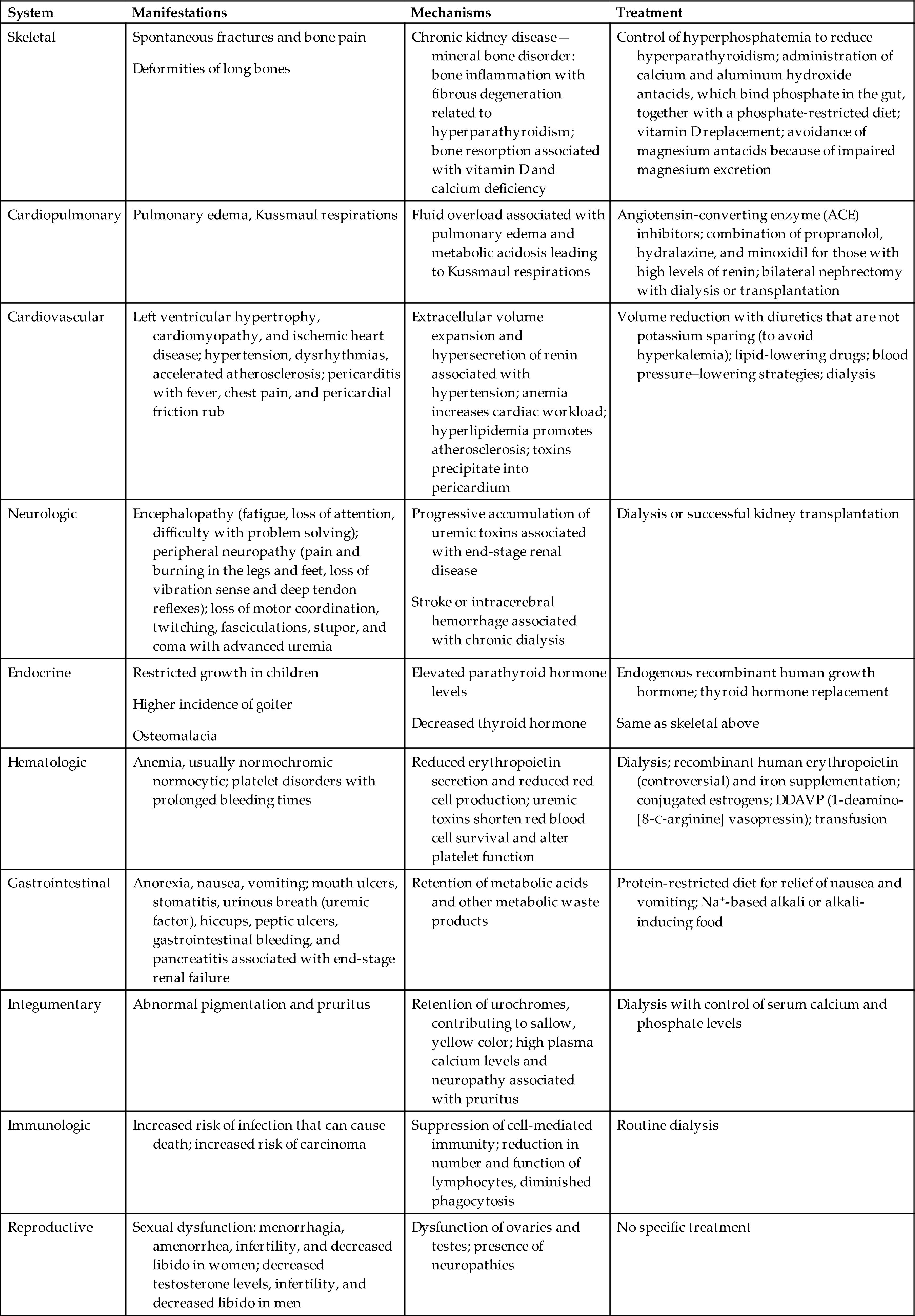

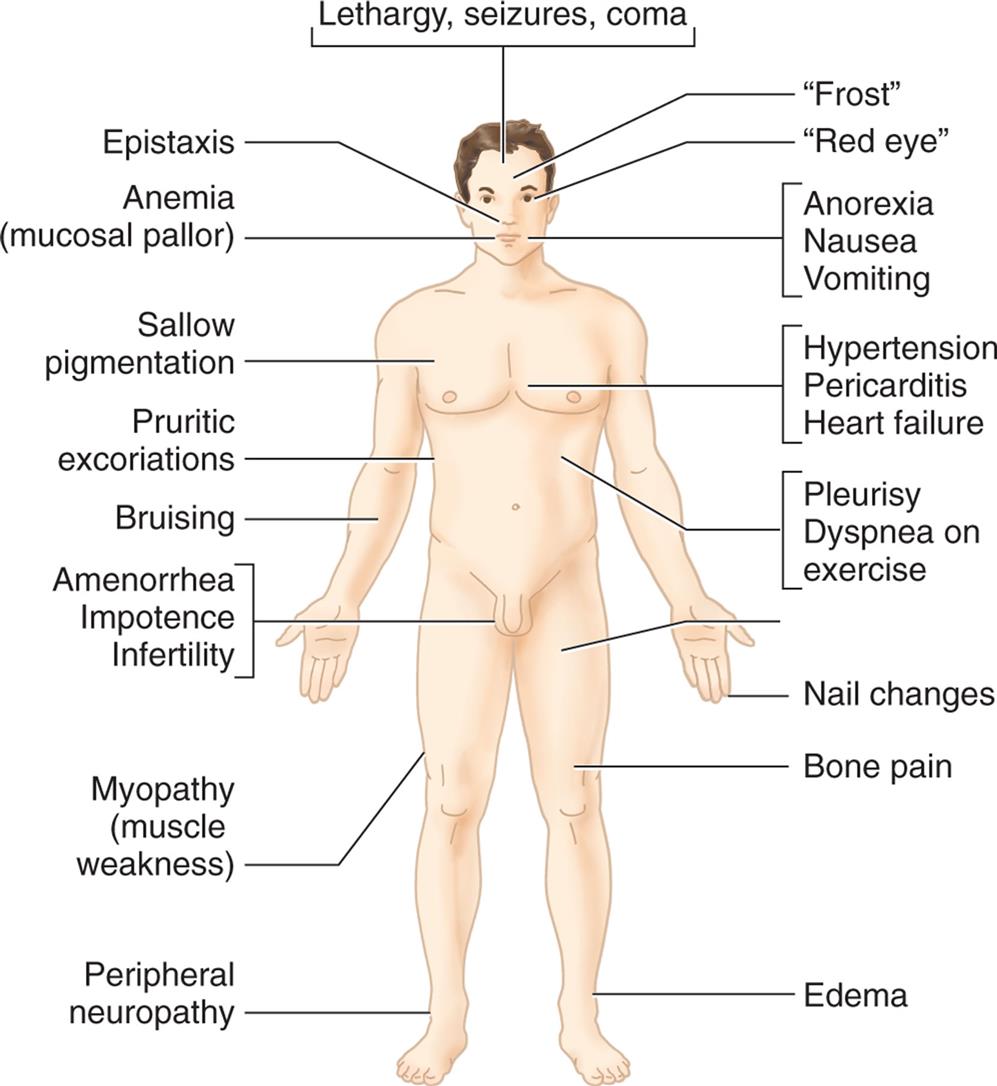

Pathophysiology