Human Reproductive Anatomy and Physiology

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer.

- 1. Define each key term listed.

- 2. Describe changes of puberty in males and females.

- 3. Identify the anatomy of the male reproductive system.

- 4. Explain the functions of the external and internal male organs in human reproduction.

- 5. Describe the influence of hormones in male reproductive processes.

- 6. Identify the anatomy of the female reproductive system.

- 7. Explain the functions of the external, internal, and accessory female organs in human reproduction.

- 8. Discuss the importance of the pelvic bones to the birth process.

- 9. Explain the menstrual cycle and the female hormones involved in the cycle.

- 10. Discuss the physiological responses of the woman during coitus.

Key Terms

biischial diameter (bī-ĬS-kē-ŭl dī-ĂM-ĭ-tĕr, p. 29)

climacteric (klī-MĂK-tĕr-ĭk, p. 30)

dyspareunia (dĭs-păh-RŪ-nē-ă, p.26)

follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (p. 30)

luteinizing hormone (LH) (p. 25)

oxytocin (ŏk-sē-TŌ-sĭn, p. 32)

spermatogenesis (spuĭr-maĭ-tō-JĔN-ĕ-sĭs, p. 24)

Understanding childbirth requires an understanding of the structures and functions of the body that make childbearing possible. This knowledge includes anatomy, physiology, sexuality, embryology of the growing fetus, and the psychosocial changes that occur in both the man and the woman. This chapter addresses the anatomy and physiology of the male and female reproductive systems.

Puberty

Before puberty, boys and girls appear very much alike except for their genitalia. Puberty involves changes in the whole body and the psyche as well as in the expectations of society toward the individual.

Puberty is a period of rapid change in the lives of boys and girls during which the reproductive systems mature and become capable of reproduction. Puberty begins when the secondary sex characteristics (e.g., pubic hair) appear. Puberty ends when mature sperm are formed or when regular menstrual cycles occur. This transition from childhood to adulthood has been identified and often celebrated by various rites of passage. Some cultures have required demonstrations of bravery, such as hunting wild animals or displays of self-defense. Ritual circumcision is another rite of passage in some cultures and religions. In the United States today, some adolescents participate in religious ceremonies such as bar or bat mitzvah or quinceañera, but for others, these ceremonies are unfamiliar. The lack of a universal “rite of passage” to identify adulthood has led to confusion for some contemporary adolescents in many industrialized nations.

Male

Male hormonal changes normally begin between 10 and 16 years of age. Outward changes become apparent when the size of the penis and testes increases and there is a general growth spurt. Testosterone, the primary male sex hormone, causes the boy to grow taller, become more muscular, and develop secondary sex characteristics such as pubic hair, facial hair, and a deeper voice. The voice deepens but is often characterized by squeaks or cracks before reaching its final pitch. Testosterone levels are constant, although levels may decrease with age to 50% of peak levels by age 80 years. Nocturnal emissions (“wet dreams”) may occur without sexual stimulation. These emissions usually do not contain sperm.

Female

The first outward change of puberty in girls is development of the breasts. The first menstrual period (menarche) occurs 2 to 2½ years later (age 11 to 15 years). Female reproductive organs mature to prepare for sexual activity and childbearing. Girls experience a growth spurt, but this growth spurt ends earlier than the growth spurt experienced by boys. A girl’s hips broaden as her pelvis assumes the wide basin shape needed for birth. Pubic hair and axillary hair appear. The quantity varies, as it does in males.

Reproductive Systems

Male

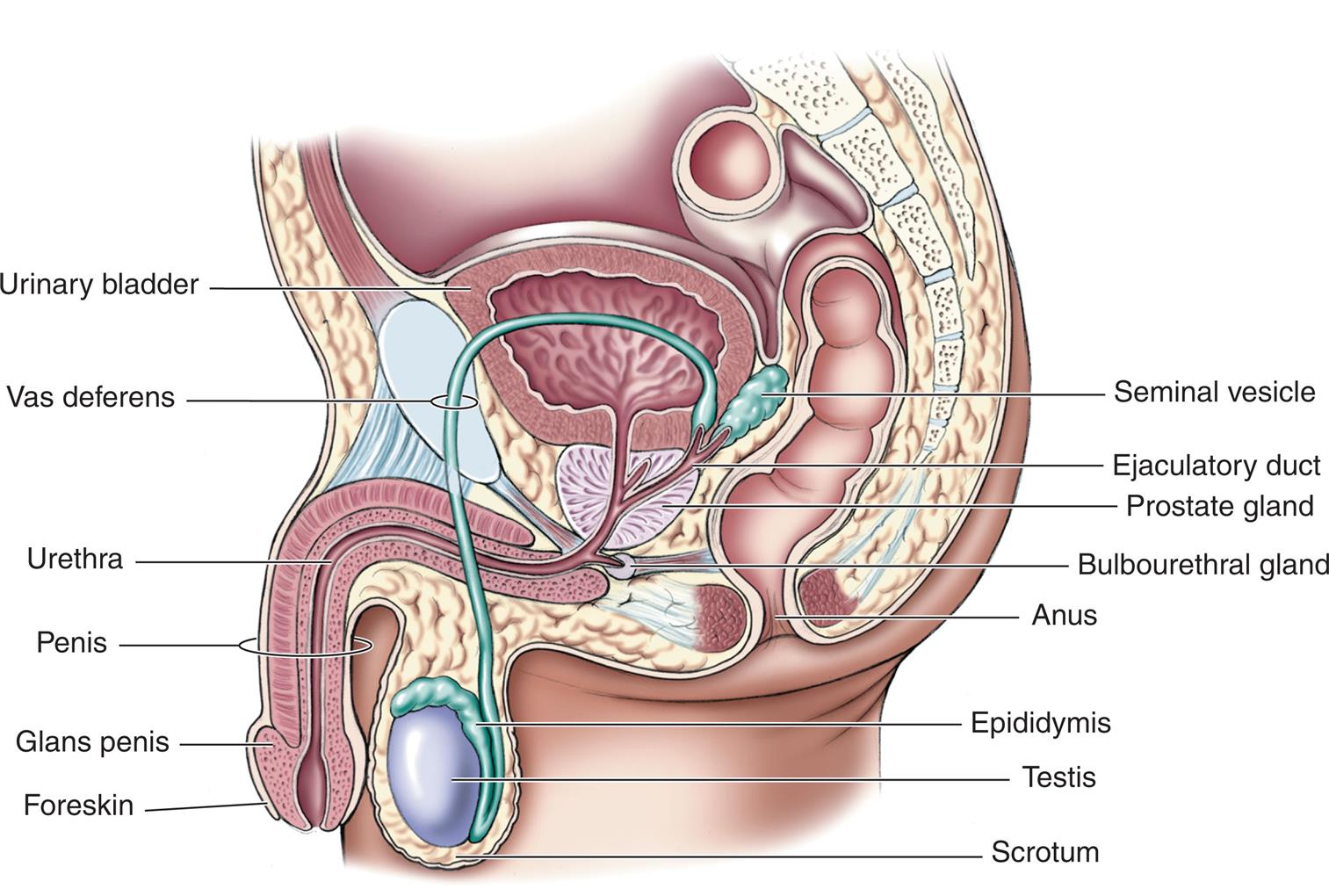

The male reproductive system consists of external and internal organs (Fig. 2.1).

Illustration of lateral view of male pelvis shows labels for structures from top to bottom as follows: urinary bladder, seminal vesicle, vas deferens, ejaculatory duct, prostate gland, bulbourethral gland, urethra, anus, penis, epididymis, testis, glans penis, foreskin, and scrotum.

External Genitalia

The penis and the scrotum, which contains the testes, are the male external genitalia.

Penis

The penis consists of the glans and the body. The glans is the rounded, distal end of the penis. It is visible on a circumcised penis but is hidden by the foreskin on an uncircumcised penis. Smegma is a cheese-like sebaceous substance that collects under the foreskin and is easily removed with basic hygiene. At the tip of the glans is an opening called the urethral meatus. The body of the penis contains the urethra (the passageway for sperm and urine) and erectile tissue (the corpus spongiosum and two corpora cavernosa). The usually flaccid penis becomes erect during sexual stimulation when blood is trapped within the spongy erectile tissues. The erection allows the penis to penetrate the woman’s vagina during sexual intercourse. The penis has two functions:

Scrotum

The scrotum is a sac that contains the testes. The scrotum is suspended from the perineum, keeping the testes away from the body and thereby lowering their temperature, which is necessary for normal sperm production (spermatogenesis).

Internal Genitalia

The internal genitalia include the testes, vas deferens, prostate, seminal vesicles, ejaculatory ducts, urethra, and accessory glands.

Testes

The testes (testicles) are a pair of oval glands housed in the scrotum. They have two functions:

Sperm are made in the convoluted seminiferous tubules that are contained within the testes. Sperm production begins at puberty and continues throughout the life span of the male.

The production of testosterone, the most abundant male sex hormone, begins with the anterior pituitary gland. Under the direction of the hypothalamus, the anterior pituitary gland secretes follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). FSH and LH initiate the production of testosterone in the Leydig cells of the testes.

Testosterone has the following effects not directly related to sexual reproduction:

These effects result in greater strength and stature and a higher hematocrit level in males than in females. Testosterone also increases the production of sebum, a fatty secretion of the sebaceous glands of the skin, and it may contribute to the development of acne during early adolescence. However, as the skin adapts to the higher levels of testosterone, acne generally recedes.

Ducts

Each epididymis, one from each testicle, stores the sperm. The sperm may remain in the epididymis for 2 to 10 days, during which time they mature and then move on to the vas deferens. Each vas deferens passes upward into the body, goes around the symphysis pubis, circles the bladder, and passes downward to form (with the ducts from the seminal vesicles) the ejaculatory ducts. The ejaculatory ducts then enter the back of the prostate gland and connect to the upper part of the urethra, which is in the penis. The urethra transports both urine from the bladder and semen from the prostate gland to the outside of the body, although not at the same time.

Accessory Glands

The accessory glands are the seminal vesicles, the prostate gland, and the bulbourethral glands, also called Cowper’s glands. The accessory glands produce secretions (seminal plasma) that have three functions:

The combined seminal plasma and sperm are called semen. Semen may be secreted during sexual intercourse before ejaculation. Therefore pregnancy may occur even if ejaculation occurs outside the vagina. Increased heat in the environment around the sperm (testes) increases the motility of the sperm but also shortens their life span. A constant increase in temperature around the testes can prevent spermatogenesis and lead to permanent sterility. (Refer to a medical-surgical nursing textbook for the testicular self-examination procedure.)

Female

The female reproductive system consists of external genitalia, internal genitalia, and accessory structures such as the mammary glands (breasts). The bony pelvis is also discussed in this chapter because of its importance in the childbearing process.

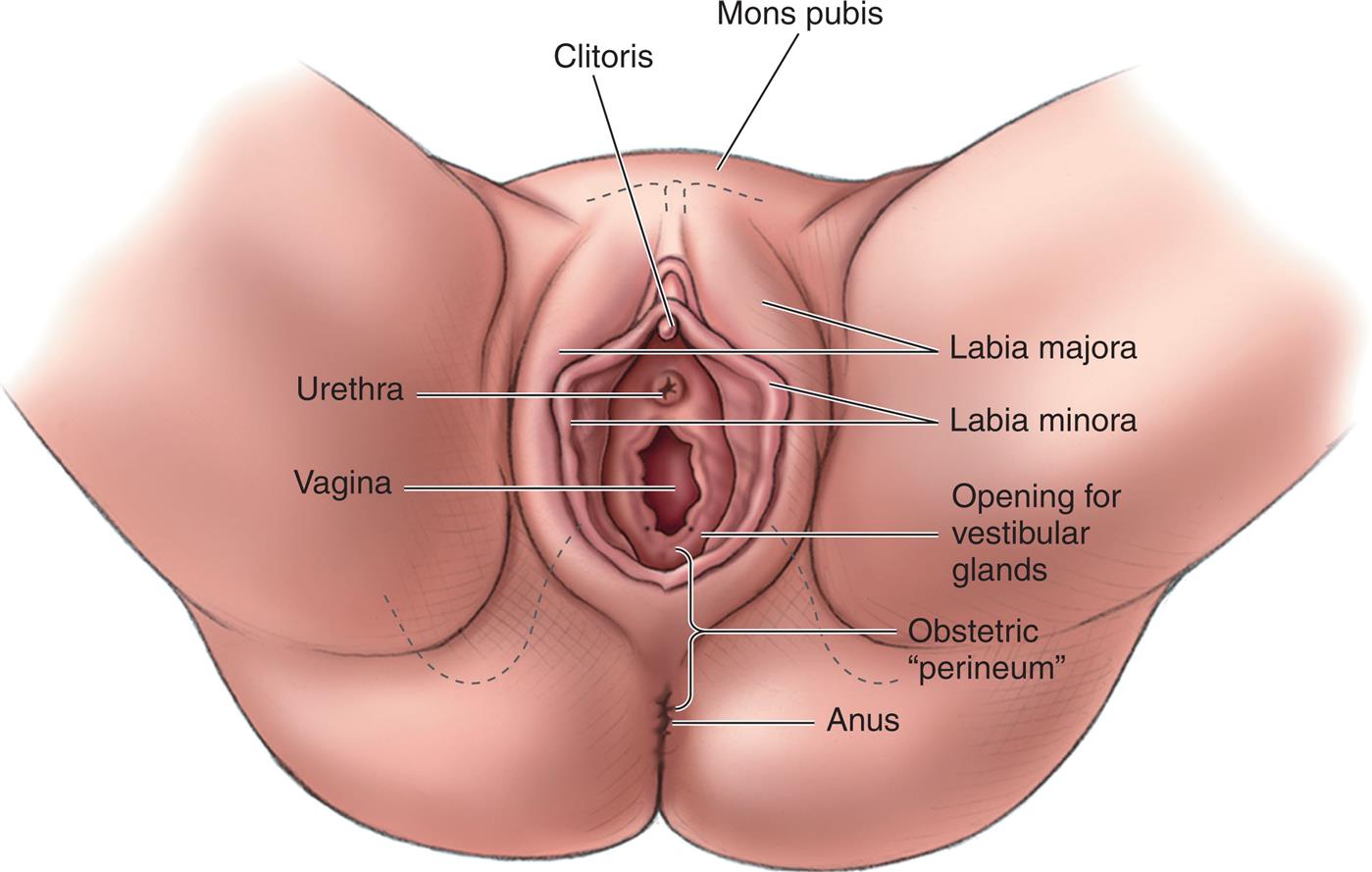

External Genitalia

The female external genitalia are collectively called the vulva. They include the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, fourchette, clitoris, vaginal vestibule, and perineum (Fig. 2.2).

Illustration of perineal view of female pelvis shows labels for structures from top to bottom as follows: Mons pubis, clitoris, labia majora, labia minora, urethra, vagina, opening for vestibular glands, obstetric perineum, and anus.

Mons Pubis

The mons pubis (mons veneris) is a pad of fatty tissue covered by coarse skin and hair. It protects the symphysis pubis and contributes to the rounded contour of the female body.

Labia Majora

The labia majora are two folds of fatty tissue on each side of the vaginal vestibule. Many small glands are located on the moist interior surface.

Labia Minora

The labia minora are two thin, soft folds of tissue that are seen when the labia majora are separated. Secretions from sebaceous glands in the labia are bactericidal to reduce infection and lubricate and protect the skin of the vulva.

Fourchette

The fourchette is a fold of tissue just below the vagina, where the labia majora and the labia minora meet. It is also known as the obstetrical perineum. Lacerations in this area often occur during childbirth.

Clitoris

The clitoris is a small, erectile body in the most anterior portion of the labia minora. It is similar in structure to the penis. Functionally, it is the most erotic, sensitive part of the female genitalia.

Vaginal Vestibule

The vaginal vestibule is the area seen when the labia minora are separated and includes five structures:

- 1. The urethral meatus lies approximately 2 cm below the clitoris. It has a fold-like appearance with a slit type of opening, and it serves as the exit for urine.

- 2. Skene ducts (paraurethral ducts) are located on each side of the urethra and provide lubrication for the urethra and the vaginal orifice.

- 3. The vaginal introitus is the division between the external and internal female genitalia.

- 4. The hymen is a thin elastic membrane that closes the vagina from the vestibule to various degrees.

- 5. The ducts of the Bartholin glands (vulvovaginal glands) provide lubrication for the vaginal introitus during sexual arousal and are normally not visible.

Perineum

The perineum is a strong, muscular area between the vaginal opening and the anus. The elastic fibers and connective tissue of the perineum allow stretching to permit the birth of the fetus. The perineum is the site of the episiotomy (incision) if performed or potential tears during childbirth. Pelvic weakness or painful intercourse (dyspareunia) may result if this tissue does not heal properly.

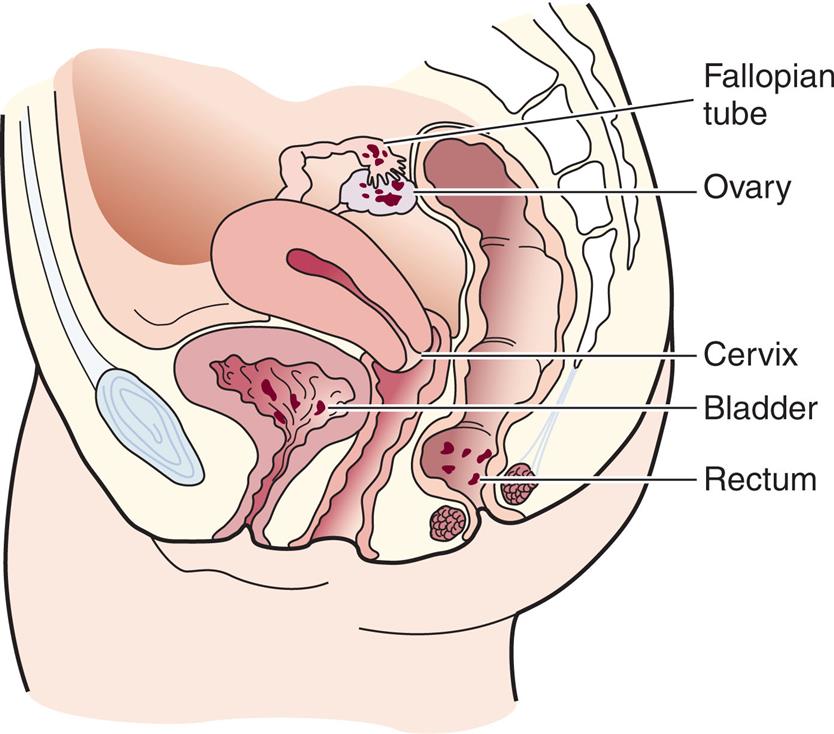

Internal Genitalia

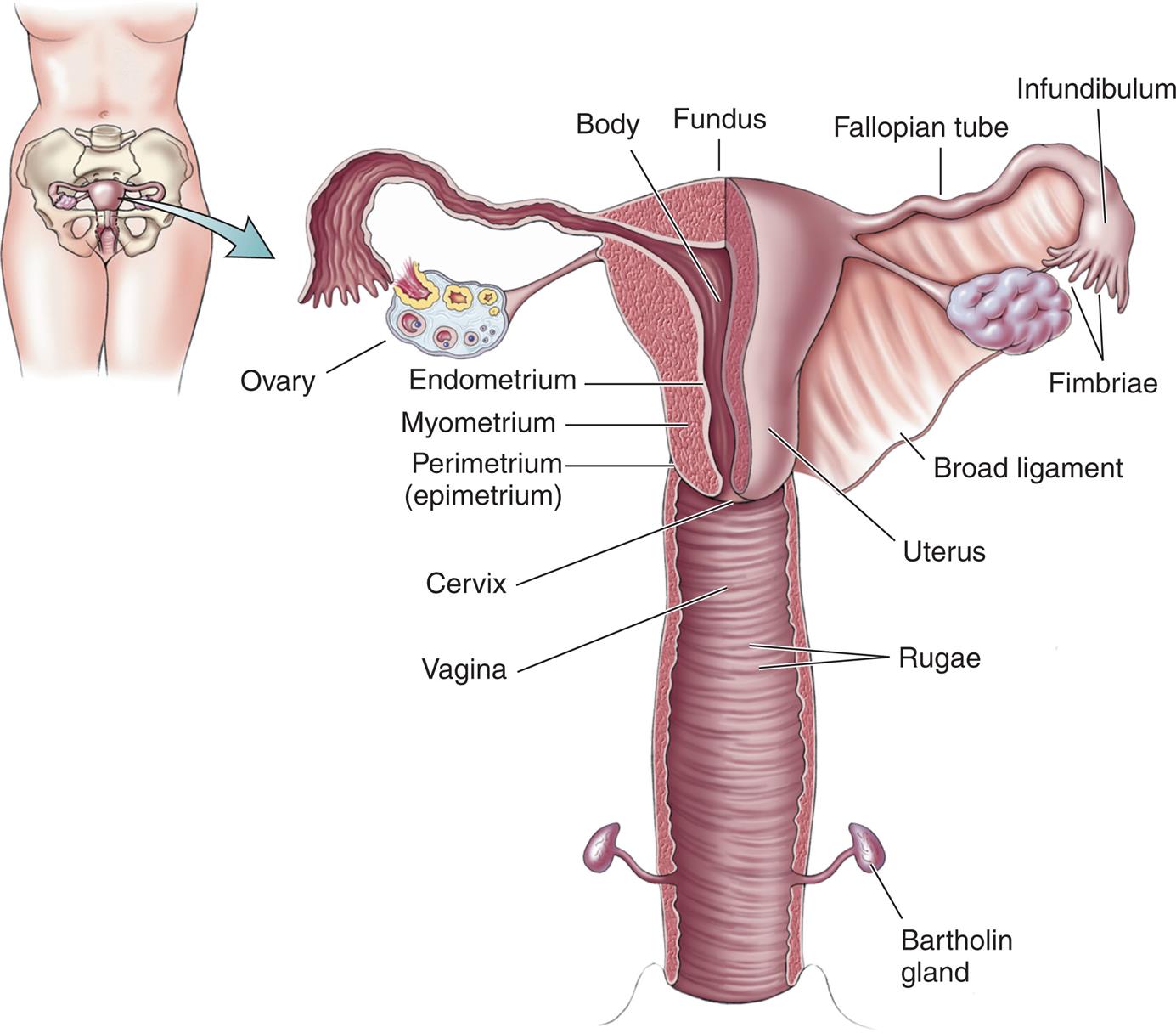

The internal genitalia are the vagina, uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. Fig. 2.3 illustrates the side view of these organs, and Fig. 2.4 illustrates the frontal view.

Illustration of female lower body with uterus shows an enlarged view of uterus. The uterus shows labels for structures from top to bottom as follows: Fundus, fallopian tube, infundibulum, fimbriae, ovary, body, uterus, endometrium, myometrium, perimetrium (epimetrium), broad ligament, cervix, vagina, rugae, and Bartholin gland.

Vagina

The vagina is a tubular structure made of muscle and membranous tissue that connects the external genitalia to the uterus. Because it meets with the cervix at a right angle, the anterior wall is about 2.5 cm (1 inch) shorter than the posterior wall, which varies from 7 to 10 cm (approximately 2.8 to 4 inches). The marked stretching of the vagina during delivery is made possible by the rugae, or transverse ridges of the mucous membrane lining. The vagina is self-cleansing and during the reproductive years maintains a normal acidic pH of 4 to 5. Antibiotic therapy, frequent douching, and excessive use of vaginal sprays, deodorant sanitary pads, or deodorant tampons may alter the self-cleansing activity.

The vagina has three functions:

Strong pelvic floor muscles stabilize and support the internal and external reproductive organs. The most important of these muscles is the levator ani, which supports the three structures that penetrate it: urethra, vagina, and rectum.

Uterus

The uterus (womb) is a hollow muscular organ in which a fertilized ovum is implanted, an embryo forms, and a fetus develops. It is shaped like an upside-down pear or light bulb. In a mature, nonpregnant woman, it weighs approximately 60 g (2 oz) and is 7.5 cm (3 inches) long, 5 cm (2 inches) wide, and 1 to 2.5 cm (0.4 to 1 inch) thick. The uterus lies between the bladder and the rectum above the vagina.

Several ligaments support the uterus. The broad ligament provides stability to the uterus in the pelvic cavity, the round ligament is surrounded by muscles that enlarge during pregnancy and keep the uterus in place, the cardinal ligaments prevent uterine prolapse, and the uterosacral ligaments are surrounded by smooth muscle and contain sensory nerve fibers that may contribute to the sensation of dysmenorrhea (painful menstruation). Stretching of the uterine ligaments as the uterus enlarges during pregnancy can cause minor discomfort to the mother.

Nerve supply

Because the autonomic nervous system innervates the reproductive system, its functions are not under voluntary (conscious) control. Therefore even a paraplegic woman can have adequate contractions for labor. Sensations for uterine contractions are carried to the central nervous system via the 11th and 12th thoracic nerve roots. Pain from the cervix and the vagina passes through the pudendal nerves. The motor fibers of the uterus arise from the seventh and eighth thoracic vertebrae. This separate motor and sensory nerve supply allows for the use of a local anesthetic without interfering with uterine contractions and is important in pain management during labor.

Anatomy

The uterus is separated into three parts: fundus, corpus, and cervix. The fundus (upper part) is broad and flat. The fallopian tubes enter the uterus on each side of the fundus. The corpus (body) is the middle portion, and it plays an active role in menstruation and pregnancy.

The fundus and the corpus have three distinct layers:

- 1. The perimetrium is the outermost or serosal layer that envelops the uterus.

- 2. The myometrium is the middle muscular layer that functions during pregnancy and birth. It has three involuntary muscle layers: a longitudinal outer layer, a figure-of-eight interlacing middle layer, and a circular inner layer that forms sphincters at the fallopian tube attachments and at the internal opening of the cervix.

- 3. The endometrium is the inner or mucosal layer that is functional during menstruation and implantation of the fertilized ovum. It is governed by cyclical hormonal changes.

The cervix (lower part) is narrow and tubular and opens into the upper vagina. The cervix consists of a cervical canal with an internal opening near the uterine corpus (internal os) and an opening into the vagina (the external os). The mucosal lining of the cervix has four functions:

Fallopian Tubes

The fallopian tubes, also called uterine tubes or oviducts, extend laterally from the uterus, one to each ovary (see Fig. 2.4). They vary in length from 8 to 13.5 cm (3 to 5.3 inches). Each tube has four sections:

- 1. The interstitial portion extends into the uterine cavity and lies within the wall of the uterus.

- 2. The isthmus is a narrow area near the uterus.

- 3. The ampulla is the wider area of the tube and is the usual site of fertilization.

- 4. The infundibulum is the funnel-like enlarged distal end of the tube. Finger-like projections from the infundibulum, called fimbriae, hover over each ovary and “capture” the ovum (egg) as it is released by the ovary at ovulation.

The four functions of the fallopian tubes are to provide the following:

- 1. A passageway in which sperm meet the ovum

- 2. The site of fertilization (usually the outer one-third of the tube)

- 3. A safe, nourishing environment for the ovum or zygote (fertilized ovum)

- 4. The means of transporting the ovum or zygote to the corpus of the uterus

Cells within the tubes have cilia (hair-like projections) that beat rhythmically to propel the ovum toward the uterus. Other cells secrete a protein-rich fluid to nourish the ovum after it leaves the ovary.

Ovaries

The ovaries are two almond-shaped glands, each about the size of a walnut. They are located in the lower abdominal cavity, one on each side of the uterus, and are held in place by ovarian and uterine ligaments. The ovaries have two functions:

At birth, every female infant has all the ova (oocytes) that will be available during her reproductive years (approximately 2 million cells). These degenerate significantly so that by adulthood the remaining oocytes number only in the thousands. Of these, only a small percentage are actually released (about 400 during the reproductive years). Every month, one ovum matures and is released from the ovary. Any ova that remain after the climacteric (the time surrounding menopause) no longer respond to hormonal stimulation to mature.

Pelvis

The bony pelvis occupies the lower portion of the trunk of the body. Four bones attached to the lower spine form the pelvis:

Each innominate bone is made up of an ilium, pubis, and ischium, which are separate during childhood but fuse by adulthood. The ilium is the lateral, flaring portion of the hip bone; the pubis is the anterior hip bone. These two bones join to form the symphysis pubis. The curved space under the symphysis pubis is called the pubic arch. The ischium is below the ilium and supports the seated body. An ischial spine, one from each ischium, juts inward to varying degrees. These ischial spines serve as a reference point for descent of the fetus during labor. The posterior pelvis consists of the sacrum and the coccyx. Five fused, triangular vertebrae at the base of the spine form the sacrum. The sacrum may jut into the pelvic cavity, causing a narrowing of the birth passageway. Below the sacrum is the coccyx, the lowest part of the spine.

The bony pelvis has three functions:

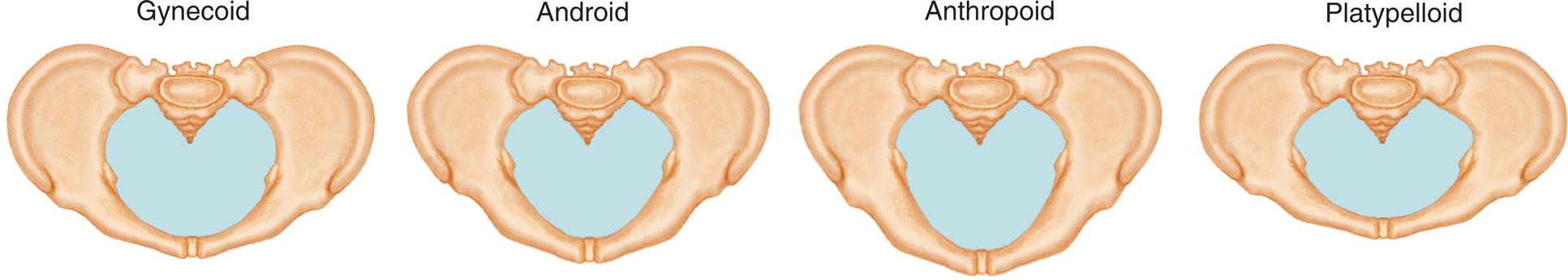

Types of Pelves

There are four basic types of pelves (Fig. 2.5). Most women have a combination of pelvic characteristics rather than having one pure type. Each type of pelvis has implications for labor and birth:

- • The gynecoid pelvis is the classic female pelvis, with rounded anterior and posterior segments. This type is most favorable for vaginal birth.

- • The android pelvis has a wedge-shaped inlet with a narrow anterior segment; it is typical of the male anatomy.

- • The anthropoid pelvis has an anteroposterior diameter that equals or exceeds its transverse diameter. The shape is a long, narrow oval. Women with this type of pelvis can usually deliver vaginally, but their infant is more likely to be born in the occiput posterior (back of the fetal head toward the mother’s sacrum) position.

- • The platypelloid pelvis has a shortened anteroposterior diameter and a flat, transverse oval shape. This type is unfavorable for vaginal birth.

False and True Pelves

The pelvis is divided into the false and true pelves by an imaginary line (linea terminalis) that extends from the sacroiliac joint to the anterior iliopubic prominence. The upper, or false, pelvis supports the enlarging uterus and guides the fetus into the true pelvis. The lower, or true, pelvis consists of the pelvic inlet, the pelvic cavity, and the pelvic outlet. The true pelvis is important because it dictates the bony limits of the birth canal.

Pelvic Diameters

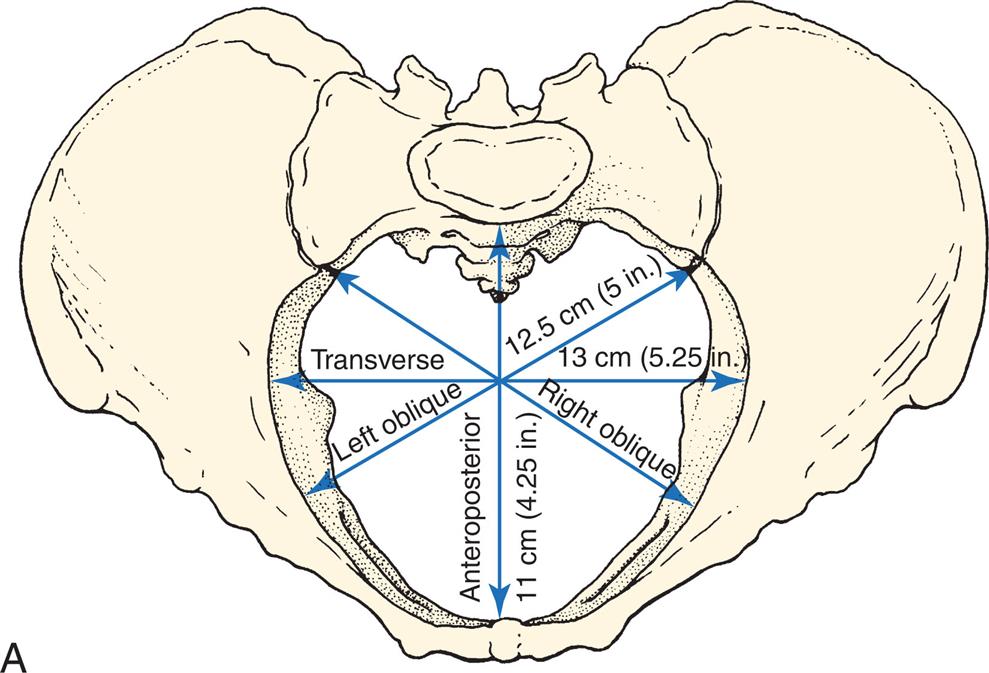

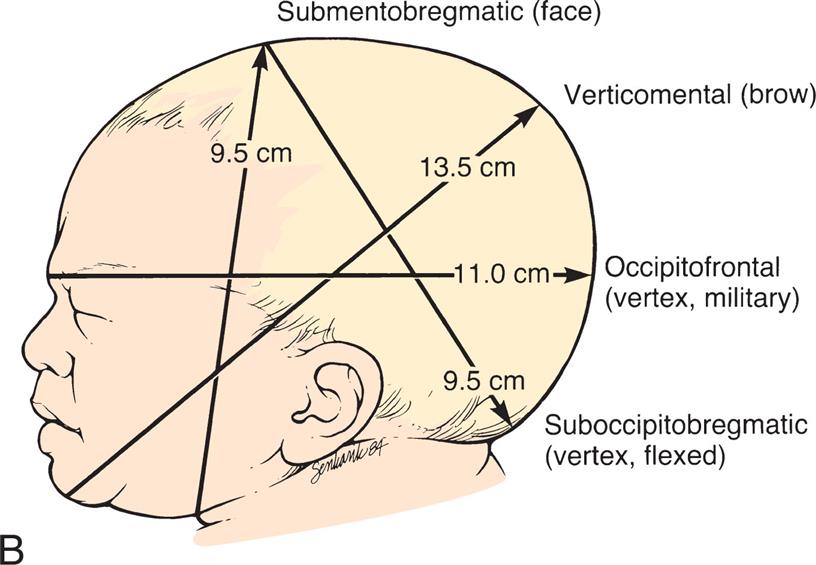

The diameters of the pelvis must be adequate for passage of the fetus during birth (Fig. 2.6).

A) Illustration of pelvic girdle shows pelvic inlet diameters including anteroposterior 11 centimeters (4.25 inches), transverse 13 centimeters (5.25 inches), and the right and left 12.5 centimeters (5 inches) oblique diameters. B) Illustration of fetal skull shows measurements of the fetal skull as follows: Submentobregmatic (face) 9.5 centimeters, Verticomental (brow) 13.5 centimeters, Occipitofrontal (vertex, military) 11.0 centimeters, and Suboccipitobregmatic (vertex, flexed) 9.5 centimeters.

Pelvic inlet

The pelvic inlet, just below the linea terminalis, has obstetrically important diameters. The anteroposterior diameter is measured between the symphysis pubis and the sacrum and is the shortest inlet diameter. The transverse diameter is measured across the linea terminalis and is the largest inlet diameter. The oblique diameters are measured from the right or left sacroiliac joint to the prominence of the linea terminalis.

Measurements of the pelvic inlet (Table 2.1) include the following:

- • Diagonal conjugate: The distance between the suprapubic angle and the sacral promontory. The health care provider assesses this measurement during a manual pelvic examination.

- • Obstetric conjugate (the smallest inlet diameter): Estimated by subtracting 1.5 to 2 cm from the diagonal conjugate (the approximate thickness of the pubic bone). This measurement determines whether the fetus can pass through the birth canal.

- • Transverse diameter: The largest diameter of the inlet. It determines the inlet’s shape.

Pelvic outlet

The transverse diameter of the outlet is a measurement of the distance between the inner surfaces of the ischial tuberosities and is known as the biischial diameter. The anteroposterior measurement of the outlet is the distance between the lower border of the symphysis pubis and the tip of the sacrum. It can be measured by vaginal examination. The sagittal diameters are measured from the middle of the transverse diameter to the pubic bone anteriorly and to the sacrococcygeal bone posteriorly. The coccyx can move or break during the passage of the fetal head, but an immobile coccyx can decrease the size of the pelvic outlet and make vaginal birth difficult. A narrow pubic arch can also affect the passage of the fetal head through the birth canal.

Adequate pelvic measurements are essential for a successful vaginal birth. Problems that can cause a pelvis to be small (e.g., a history of a pelvic fracture or rickets) potentially indicate that delivery by cesarean section will be necessary.

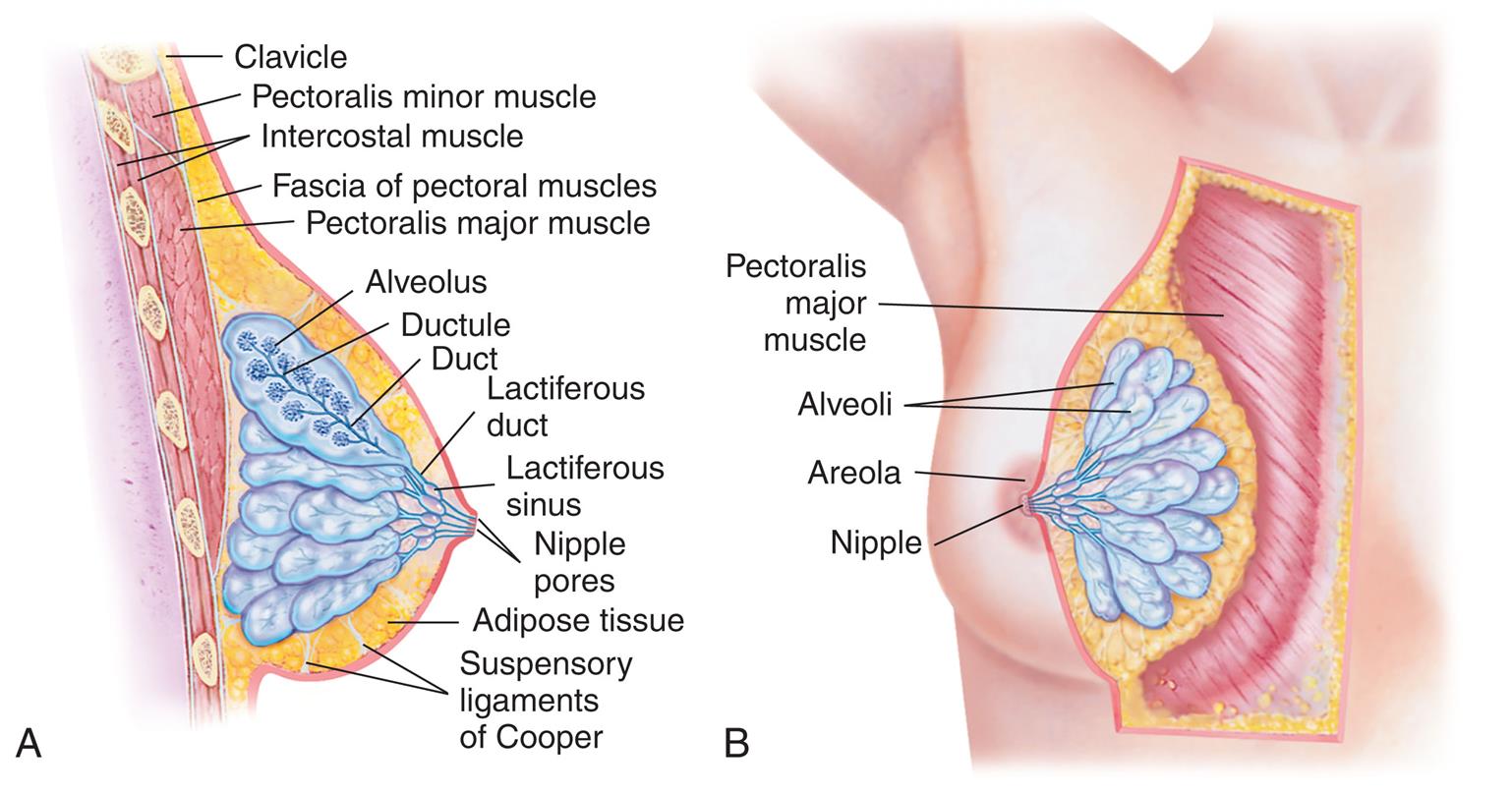

Breasts

Female breasts (mammary glands) are accessory organs of reproduction. They produce milk after birth to provide nourishment and maternal antibodies for the infant (Fig. 2.7). The nipple, in the center of each breast, is surrounded by a pigmented areola. Montgomery glands (Montgomery tubercles) are small sebaceous glands in the areola that secrete a substance to lubricate and protect the breasts during lactation.

A) Illustration of lateral view of breast shows labels for structures from bottom to top as follows: Suspensory ligaments of Cooper, adipose tissue, nipple pores, lactiferous sinus, lactiferous duct, duct, ductule, alveolus, pectoralis major muscle, fascia of pectoral muscles, intercostal muscle, pectoralis minor muscle, and clavicle. B) Illustration of frontal view of breast shows labels for structures from top to bottom as follows: Pectoralis major muscle, alveoli, areola, and nipple.

Each breast is composed of 15 to 24 lobes arranged like the spokes of a wheel. Adipose (fatty) and fibrous tissues separate the lobes. The adipose tissue affects size and firmness and gives the breasts a smooth outline. Breast size is primarily determined by the amount of fatty tissue and is unrelated to a woman’s ability to produce milk.

Alveoli (lobules) are the glands that secrete milk. They empty into approximately 20 separate lactiferous (milk-carrying) ducts. Milk is stored briefly in widened areas of the ducts, called ampullae or lactiferous sinuses.

Reproductive Cycle and Menstruation

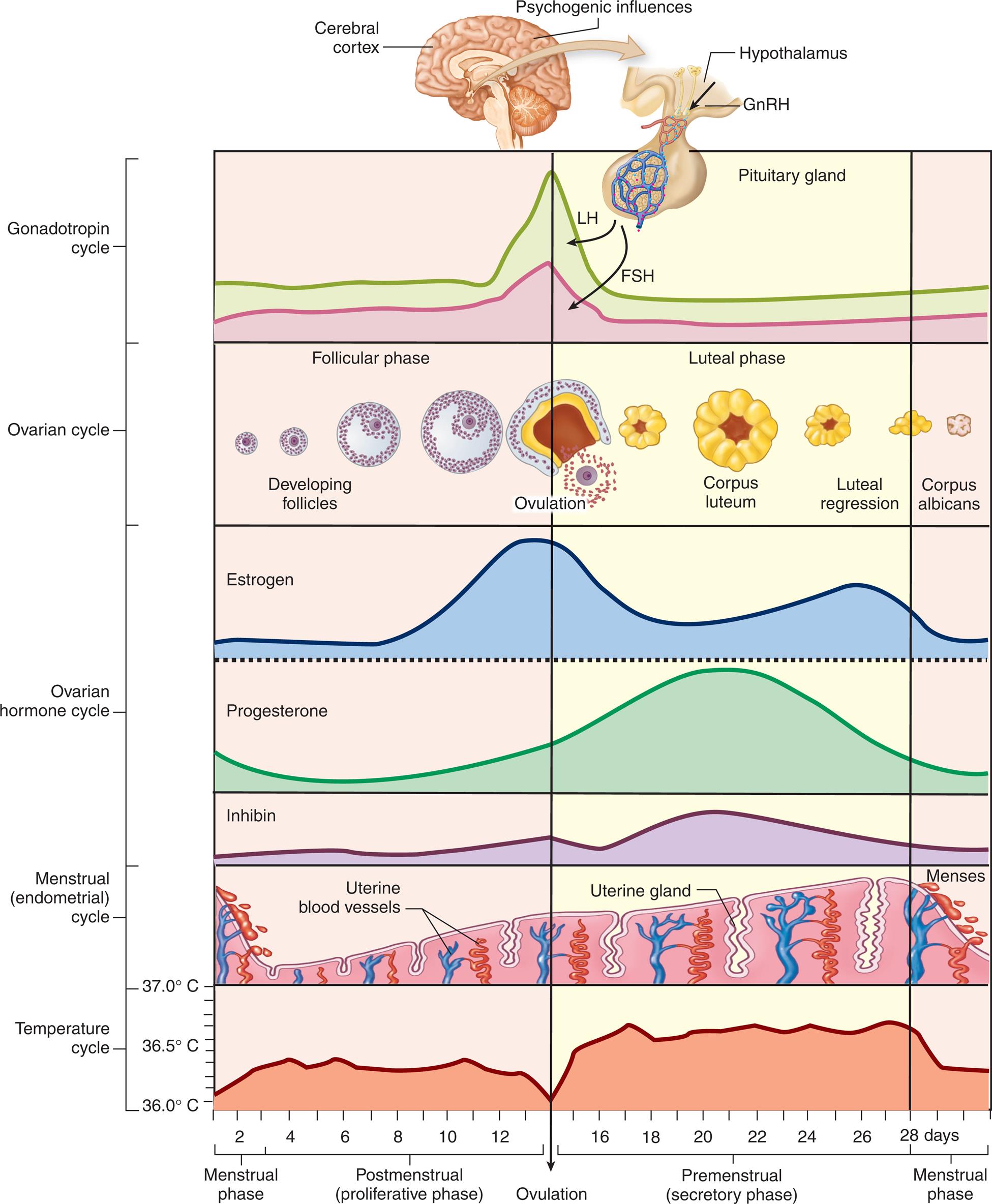

The female reproductive cycle consists of regular changes in secretions of the anterior pituitary gland, the ovary, and the endometrial lining of the uterus (Fig. 2.8). The anterior pituitary gland, in response to the hypothalamus, secretes follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and LH. FSH stimulates maturation of a follicle in the ovary that contains a single ovum. Several follicles start maturing during each cycle, but usually only one reaches final maturity. The maturing ovum and the corpus luteum (the follicle left empty after the ovum is released) produce increasing amounts of estrogen and progesterone, which leads to enlargement of the endometrium. A surge in LH stimulates final maturation and the release of an ovum. Approximately 2 days before ovulation, the vaginal secretions increase noticeably.

Set of 5 graphs show gonadotropic, ovarian, ovarian-hormone, menstrual and temperature cycles where all of them together constitute the twenty-eight-day female reproductive cycles and ovulation occurs on the fourteenth day. The changes in body temperature during the reproductive cycles are illustrated in temperature cycle. The endometrial wall changes are illustrated in menstrual cycle. The levels of estrogens, progesterone, and Inhibin are illustrated in ovarian hormone cycle, where the peak for estrogens appear around the ovulation, and peak for inhibin and progesterone appear after ovulation. The follicles develop during follicular phase, and luteal regression of the corpus luteum occurs in luteal phase of ovarian cycle. The levels of L H and F S H, are shown in gonadotropic cycle that peak across ovulation (amount of F S H is lower than L H), where the lower part of the hypothalamus in the brain under psychogenic influences release follicle stimulating hormone (F S H) and luteinizing hormone (L H )."x

Ovulation occurs when a mature ovum is released from the follicle about 14 days before the onset of the next menstrual period. The corpus luteum turns yellow (luteinizing) immediately after ovulation and secretes increasing quantities of progesterone to prepare the uterine lining for a fertilized ovum. Approximately 12 days after ovulation, the corpus luteum degenerates if fertilization has not occurred, and progesterone and estrogen levels decrease. The drop in estrogen and progesterone levels causes the endometrium to break down, resulting in menstruation. The anterior pituitary gland secretes more FSH and LH, beginning a new cycle.

The beginning of menstruation, called menarche, occurs at about age 11 to 15 years. Early cycles are often irregular and may be anovulatory. Regular cycles are usually established within 6 months to 2 years of the menarche. In an average cycle, the flow (menses) occurs every 28 days, plus or minus 5 to 10 days. The flow itself lasts from 2 to 5 days, with a blood loss of 30 to 40 mL and an additional loss of 30 to 50 mL of serous fluid. Fibrinolysin is contained in the necrotic endometrium being expelled, and therefore clots are not normally seen in the menstrual discharge.

The climacteric is a period of years during which the woman’s ability to reproduce gradually declines. Menopause refers to the final menstrual period, although in casual use the terms menopause and climacteric are often used interchangeably.

The Human Sexual Response

There are four phases of the human sexual response:

- 1. Excitement: Heart rate and blood pressure increase; nipples become erect.

- 2. Plateau: Skin flushes; erection occurs; semen appears on tip of penis.

- 3. Orgasmic: Involuntary muscle spasms of the rectum, the vagina, and the uterus occur; ejaculation occurs.

- 4. Resolution: Engorgement resolves; vital signs return to normal.

Physiology of the Male Sex Act

The male psyche can initiate or inhibit the sexual response. The massaging action of intercourse on the glans penis stimulates sensitive nerves that send impulses to the sacral area of the spinal cord and to the brain. Stimulation of nerves supplying the prostate and scrotum enhances sensations. The parasympathetic nerve fibers cause relaxation of penile arteries, which fill the cavernous sinuses of the shaft of the penis that stretch the erectile tissue so that the penis becomes firm and elongated (erection). The same nerve impulses cause the urethral glands to secrete mucus to aid in lubrication for sperm motility. The sympathetic nervous system then stimulates the spinal nerves to contract the vas deferens and cause expulsion of the sperm into the urethra (emission). Contraction of the muscle of the prostate gland and seminal vesicles expels prostatic and seminal fluid into the urethra, contributing to the flow and motility of the sperm. This full sensation in the urethra stimulates nerves in the sacral region of the spinal cord that cause rhythmical contraction of the penile erectile tissues and urethra and skeletal muscles in the shaft of the penis, which expel the semen from the urethra (ejaculation). The period of emission and ejaculation is called male orgasm.

Within minutes, erection ceases (resolution), the cavernous sinuses empty, penile arteries contract, and the penis becomes flaccid. Sperm can reach the woman’s fallopian tube within 5 minutes and can remain viable in the female reproductive tract for 4 to 5 days. Of the millions of sperm contained in the ejaculate, a few thousand reach each fallopian tube, but only one fertilizes the ovum. The sphincter at the base of the bladder closes during ejaculation so that sperm does not enter the bladder and urine cannot be expelled.

Physiology of the Female Sex Act

The female psyche can initiate or inhibit the sexual responses. Local stimulation to the breasts, vulva, vagina, and perineum creates sexual sensations. The sensitive nerves in the glans of the clitoris send signals to the sacral areas of the spinal cord, and these signals are transmitted to the brain. Parasympathetic nerves from the sacral plexus return signals to the erectile tissue around the vaginal introitus, dilating and filling the arteries and resulting in a tightening of the vagina around the penis. These signals stimulate the Bartholin glands at the vaginal introitus to secrete mucus that aids in vaginal lubrication. The parasympathetic nervous system causes the perineal muscles and other muscles in the body to contract. The posterior pituitary gland secretes oxytocin, which stimulates contraction of the uterus and dilation of the cervical canal. This process (orgasm) is believed to aid in the transport of the sperm to the fallopian tubes. (This process is also the reason why sexual abstention is advised when there is a high risk for miscarriage or preterm labor.)

Following orgasm, the muscles relax (resolution), and this is usually accompanied by a sense of relaxed satisfaction. The egg lives for only 24 hours after ovulation; sperm must be available during that time if fertilization is to occur.

Get Ready for the NCLEX® Examination!

Key Points

- • Puberty is the time when the reproductive organs mature to become capable of reproduction and secondary sex characteristics develop.

- • A sexually active girl can become pregnant before her first menstrual period because ovulation occurs before menstruation.

- • At birth, every female has all the ova that will be available during her reproductive years.

- • Testosterone is the principal male hormone. Estrogen and progesterone are the principal female hormones. Testosterone secretion continues throughout a man’s life, but estrogen and progesterone secretions are very low after a woman reaches the climacteric.

- • The penis and scrotum are the male external genitalia. The scrotum keeps the testes cooler than the rest of the body, promoting normal sperm production.

- • The two main functions of the testes are to manufacture sperm and to secrete male hormones (androgens), primarily testosterone.

- • The myometrium (middle muscular uterine layer) is functional in pregnancy and labor. The endometrium (inner uterine layer) is functional in menstruation and implantation of a fertilized ovum.

- • The female breasts are composed of fatty and fibrous tissue and of glands that can secrete milk. The size of a woman’s breasts is determined by the amount of fatty tissue and does not influence her ability to secrete milk.

- • The female reproductive cycle consists of regular changes in hormone secretions from the anterior pituitary gland and the ovary, maturation and release of an ovum, and buildup and breakdown of the uterine lining.

- • There are four basic pelvic shapes, but women often have a combination of characteristics. The gynecoid pelvis is the most favorable for vaginal birth.

- • The pelvis is divided into a false pelvis above the linea terminalis and the true pelvis below this line. The true pelvis is most important in the childbirth process. The true pelvis is further divided into the pelvic inlet, the pelvic cavity, and the pelvic outlet.

- • The egg lives for only 24 hours after ovulation, and fertilization must occur during that time.

Additional Learning Resources

![]() Go to your Study Guide for additional learning activities to help you master this chapter content.

Go to your Study Guide for additional learning activities to help you master this chapter content.

Go to your Evolve website (http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer) for the following learning resources:

- • Animations

- • Answer Guidelines for Critical Thinking Questions

- • Answers and Rationales for Review Questions for the NCLEX Examination

- • Glossary with English and Spanish pronunciations

- • Interactive Review Questions for the NCLEX Examination

- • Patient Teaching Plans in English and Spanish

- • Skills Performance Checklists

- • Video clips and more!

Online Resources

Online Resources

- • Family Support Group: https://www.4parents.org

- • Fetal Diagnostic Centers: https://www.fetal.com

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

- 1. Spermatozoa are produced in the:

- 2. A woman can keep a diary of her menstrual cycles to help determine her fertile period. She understands that after ovulation she will remain fertile for:

- 3. Which data indicate that a woman may have pelvic dimensions that would be inadequate for a normal vaginal delivery? A woman with a(n):

- 4. The muscular layer of the uterus that is the functional unit in pregnancy and labor is the:

- 5. During a prenatal clinic visit, a woman states that she probably will not plan to breastfeed her infant because she has very small breasts and believes she cannot provide adequate milk for a full-term infant. The best response of the nurse would be:

- 1. “Ask the physician if he or she will prescribe hormones to build up the breasts.”

- 2. “I can provide you with exercises that will build up your breast tissue.”

- 3. “The fluid intake of the mother will determine the milk output.”

- 4. “The size of the breast has no relationship to the ability to produce adequate milk.”

- 6. The nurse is leading a class discussing ovulation and menstruation. The nurse explains that ovulation occurs:

Critical Thinking Questions

- 1. A patient is admitted to the labor unit. She has not had any prenatal care. Her history shows that she sustained a fractured pelvis from an automobile accident several years previously. The patient states she is interested in natural childbirth. What is the nurse’s best response?

- 2. An adolescent boy fears he is becoming incontinent because he notices his pajama pants are wet on occasion when he awakes in the morning. He asks if there is medicine to stop this problem. What is the best response from the nurse?