Preterm and Postterm Newborns

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer.

- 1. Define each key term listed.

- 2. Differentiate between the preterm and the low-birth-weight newborn.

- 3. List three causes of preterm birth.

- 4. Describe selected problems and needs of preterm newborns and the nursing goals associated with each problem.

- 5. Describe the symptoms of cold stress and methods of maintaining thermoregulation.

- 6. Contrast the techniques for feeding preterm and full-term newborns.

- 7. Discuss two ways to help facilitate maternal-infant bonding for a preterm newborn.

- 8. Describe the family reaction to preterm infants and nursing interventions.

- 9. List three characteristics of the postterm infant.

Key Terms

Ballard scoring system (p. 321)

bradycardia (brād-ĕ-KĂHR-dē-ă, p. 325)

bronchopulmonary dysplasia (brŏn-kō-PŬL-mŏ-năr-ē dĭs-PLĀ-zhă, p. 325)

hyperbilirubinemia (hī-pŭr-bĭl-ē-rū-bĭ-NĒ-mē-ă, p. 328)

hypocalcemia (hī-pō-kăl-SĒ-mē-ă, p. 327)

hypoglycemia (hī-pō-glī-SĒ-mē-ă, p. 326)

large for gestational age (LGA) (p. 321)

necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) (NĔK-rō-tīz-ĭng ĕn-tĕr-ō-kō-LĪ-tĭs, p. 328)

neutral thermal environment (p. 329)

respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) (p. 324)

retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) (p. 327)

small for gestational age (SGA) (p. 321)

surfactant (sŭr-FĂK-tănt, p. 324)

total parenteral nutrition (TPN) (TŌT-ăl pă-RĔN-tŭr-ăl nū-TRĬ-shŭn, p. 331)

The Periviable Newborn

A periviable birth is defined as one that occurs between 20 and 25 weeks’ gestation (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2017). Approximately 0.5% of all births occur before the third trimester. Delivery before 24 weeks’ gestation results in only 5% survival, often with significant morbidity and neurological impairment. The therapeutic approach before birth may have included tocolytic therapy to prevent labor, and administration of antenatal steroids, antibiotics for ruptured membranes, and Group B Streptococcus prophylaxis. The births should occur in centers with appropriate intensive care unit (ICU) support services, and there should be informed parent preferences with support and guidance. The staff should respect the plan of care and communicate any changes at shift hand-off.

The Preterm Newborn

The preterm (also known as premature) newborn is the most common admission to the intensive care nursery. With increased specialization and sophisticated monitoring techniques, many infants who in the past would have died are now surviving. The nurse’s role continues to be increasingly complex, with greater emphasis placed on subtle clinical observations and technology. In acquainting the student with the preterm infant, one goal of this chapter is to encourage an appreciation of the preterm infant’s struggle for survival and the intense responsibility placed on those entrusted with the infant’s care.

The words preterm and premature are used synonymously, although the former is now considered more accurate. Any newborn whose life or quality of existence is threatened is considered to be in a high-risk category and requires close supervision by professionals in a special neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Preterm newborns constitute a majority of these patients. Preterm birth is responsible for more deaths during the first year of life than any other single factor. Preterm infants also have a higher percentage of birth defects. Prematurity and low birth weight are often concomitant, and both factors are associated with increased neonatal morbidity and mortality. The less an infant weighs at birth, the greater the risks to life during delivery and immediately thereafter.

In the past, a newborn was classified solely by birth weight. The emphasis is now on gestational age and level of maturation. Fig. 13.1 shows two different term infants of the same gestational age. One newborn would be classified as small for gestational age (SGA), which may be the result of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), because of its weight and size. Term infants over 4000 g (8.8 lb) may be classified as large for gestational age (LGA).

Current data indicates that intrauterine growth rates are not the same for all infants and that individual factors must be considered. Gestational age refers to the actual time, from conception to birth, that the fetus remains in the uterus. A preterm or premature infant is an infant born less than 37 weeks’ gestation. A late preterm infant is an infant born between 34 weeks and 36 weeks and 6 days of gestation. An early term infant is born between 37 weeks and 38 weeks and 6 days of gestation. The full-term infant is one born between 39 and 40 weeks and 6 days, and the late-term infant is one born between 41 weeks and 41 weeks and 6 days. The postterm infant is born beyond 42 weeks’ gestation. Except for full term infants, infants in all of these categories, newly defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), are considered high-risk newborns, regardless of birth weight (Simham and Romero, 2020).

The ACOG has defined “term pregnancy” and “term infant” to emphasize that every week in utero up to 39 weeks is important for optimal fetal development. A low-birth-weight (LBW) infant weighs 2500 g (5.8 lb) or less regardless of gestational age.

When gestational age and birthweight are evaluated together, the definition of small for gestational age (SGA) is birthweight below the 10th percentile for that gestational age. Average gestational age (AGA) is an infant between the 10th and 90th percentile for that gestational age. A large for gestational age (LGA) infant is above the 90th percentile for that gestational age (Simham and Romero, 2020). An infant may have a low birth weight because of IUGR, or the infant may just be SGA; regardless, both are treated as high-risk newborns.

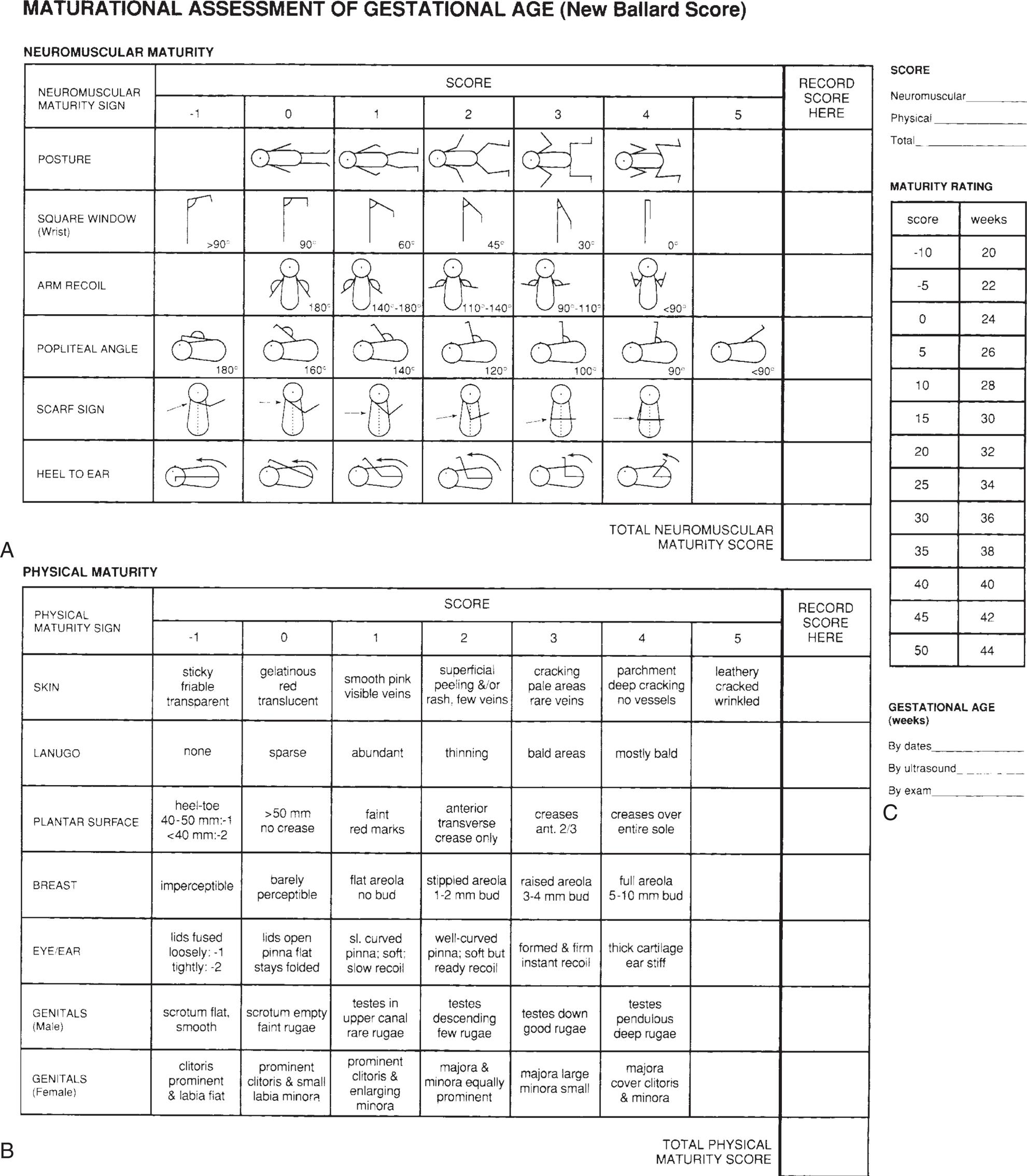

A standardized method used to estimate gestational age within 1 to 2 weeks is the Ballard scoring system, which is based on the infant’s external characteristics and neurological development (Figs. 13.2 and 13.3). The Ballard score, the estimated gestational age based on the mother’s last normal menstrual period, and ultrasound evaluations all are methods used to evaluate the gestational age of the newborn infant.

Two charts, A and B, are titled maturational assessment of gestational age (New Ballard score). Chart A titled neuromuscular maturity shows details of posture, square window (wrist), arm recoil, popliteal angle, scarf sign, and heel to ear. Chart B titled physical maturity shows the details of skin, lanugo, plantar surface, breast, eye or ear, genitals (male), and genitals (female).

A) Close-up of prematured baby lying supine with arms up and legs wide. B) Close-up of a healthy baby with knees and elbows flexed. C) Close-up of a hand bringing heel of newborn above the face. D) Close-up of a hand bringing right arm of newborn to left shoulder. The newborn wears an identification band. E) Close-up of newborn with electrodes attached to the chest. A gloved hand pulls right arm of newborn to one side.

The level of maturation refers to how well developed the infant is at birth and the ability of the organs to function outside the uterus. The physician can determine much about the maturity of the newborn by careful physical examination, observation of behavior, and family history. An infant who is born at 34 weeks of gestation, weighs 1588 g (3.8 lb) at birth, has not been damaged by multifactorial birth defects, and has had a well-functioning placenta may be healthier than a full-term, “small for date” infant whose placenta was insufficient for any of a number of reasons. The former infant is also probably in better condition than the heavy but immature infant of a diabetic mother. Each infant has different and distinct needs.

Causes of Preterm Birth

The predisposing causes of preterm birth are numerous; in many instances, the cause is unknown. Prematurity may be caused by multiple births, illness of the mother (e.g., malnutrition, heart disease, diabetes mellitus, or infectious conditions), or the hazards of pregnancy itself, such as gestational hypertension, placental abnormalities that may result in premature rupture of the membranes, placenta previa (in which the placenta lies over the cervix instead of higher in the uterus), and premature separation of the placenta. Studies also indicate the relationships between prematurity and poverty, smoking, alcohol consumption, and abuse of cocaine and other drugs.

Adequate prenatal care to prevent preterm birth is extremely important. Some preterm infants are born into families with numerous other problems. The parents may not be prepared to handle the additional financial and emotional strain imposed by a preterm infant. After delivery, early parental interaction with the infant is recognized as essential to the bonding (attachment) process. The presence of parents in special care nurseries is commonplace. Multidisciplinary care (including parent aides and other types of home support and assistance) is vital, particularly because current studies indicate a correlation between high-risk births and child abuse and neglect.

Physical Characteristics

Preterm birth deprives the newborn of the complete benefits of intrauterine life. The skin is transparent and loose. Superficial veins may be seen beneath the abdomen and scalp. There is a lack of subcutaneous fat, and fine hair (lanugo) covers the forehead, shoulders, and arms. The cheese-like vernix caseosa is abundant. The extremities appear short. The soles of the feet have few creases, and the abdomen protrudes. The nails are short. The genitalia are small. In girls, the labia majora may be open (see Fig. 13.3).

Related Problems

Inadequate Respiratory Function

Important structural changes occur in the fetal lungs during the second half of the pregnancy. The alveoli, or air sacs, enlarge, which brings them closer to the capillaries in the lungs. The failure of this phenomenon to occur leads to many deaths attributed to previability (pre, “before,” vita, “life,” and able “capable of”). In addition, the muscles that move the chest are not fully developed; the abdomen is distended, creating pressure on the diaphragm; the stimulation of the respiratory center in the brain is immature; and the gag and cough reflexes are weak because of immature nerve supply. Oxygen may be required and can be administered via nasal catheter, incubator, or oxygen hood (Fig. 13.4). The oxygen must be warmed and humidified to prevent drying of the mucous membranes. Mechanical ventilation may be required. Oxygen saturation levels should be monitored. The infant is usually admitted to the NICU.

Oxygen is administered to this infant by means of a plastic hood. The infant is accessible for treatments without interrupting the oxygen supply.

Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), also called hyaline membrane disease, is a result of lung immaturity, which leads to reduced gas exchange. An estimated 60% to 80% of neonatal deaths of infants born before 28 weeks’ gestation, and 15% to 30% of infants born between 32 and 36 weeks’ gestation result from RDS or its complications (Ahlfeld, 2020). In this disease, there is a deficient synthesis or release of surfactant, a chemical in the lungs. Surfactant is high in lecithin, a fatty protein necessary for the absorption of oxygen by the lungs. Testing for the lecithin/sphingomyelin (L/S) ratio provides information about the amount of surfactant in amniotic fluid.

Manifestations

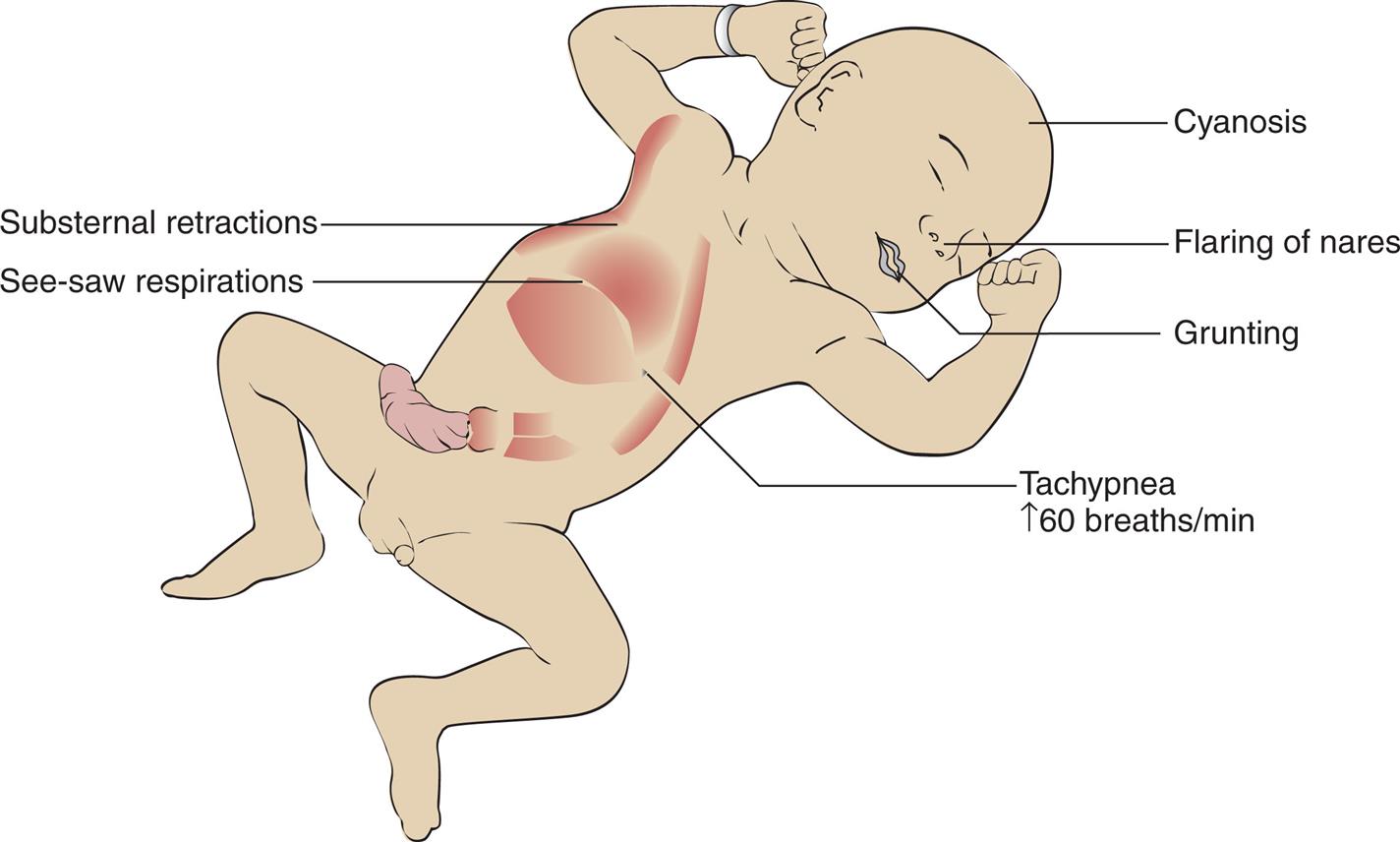

In general, the symptoms of respiratory distress are apparent after delivery, but they may not manifest for several hours (Fig. 13.5). Respirations increase to 60 breaths/minute or more. Rapid respirations (tachypnea) are accompanied by grunt-like sounds, nasal flaring, cyanosis, and intercostal and sternal retractions. Edema, lassitude, and apnea occur as the condition becomes more severe. Mechanical ventilation may be necessary. The treatment of these infants is ideally carried out in the NICU.

Treatment

Surfactant begins to appear in the fetal alveoli at approximately 24 weeks of gestation and is at a level to enable the infant to breathe adequately at birth by 34 weeks of gestation. If insufficient amounts of surfactant are detected through amniocentesis, it is possible to increase its production by giving the mother injections of corticosteroids, such as betamethasone. Administration 1 or 2 days before delivery may reduce the chances of RDS. In preterm newborns, surfactant can be administered via endotracheal (ET) tube at birth or when symptoms of RDS occur, with improvement of lung function seen within 72 hours. Surfactant production is altered during episodes of cold stress or hypoxia and when there is poor tissue perfusion, and such conditions are often present in the preterm infant in the first days of life.

Vital signs are monitored closely, arterial blood gases are analyzed, and the infant is placed in a warm incubator with gentle and minimal handling to conserve energy. The concept of cluster care involves combining and coordinating the handling required for assessment and treatments to provide adequate blocks of time for uninterrupted rest. Intravenous fluids are prescribed, and the nurse observes for signs of overhydration or dehydration. Oxygen therapy may be given via hood (see Fig. 13.4) or ventilator in concentrations necessary to maintain adequate tissue perfusion. Oxygen toxicity is a high risk for infants receiving prolonged treatment with high concentrations of oxygen. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia is the toxic response of the lung to oxygen therapy. Atelectasis, edema, and thickening of the membranes of the lung interfere with ventilation. This often results in prolonged dependence on supplemental oxygen and ventilators and has long-term complications.

Apnea

Apnea is defined as the cessation of breathing for 20 seconds or longer. It is not uncommon in the preterm newborn and is believed to be related to immaturity of the nervous system. Apnea of a term infant is rare and usually associated with serious pathology. An apneic episode may be accompanied by bradycardia (heart rate of fewer than 110 beats/minute) and cyanosis. Apnea monitors alert nurses to this complication. Gentle rubbing of the infant’s feet, ankles, and back may stimulate breathing after this occurrence. When these measures fail, suctioning of the nose and mouth and raising of the infant’s head to a semi-Fowler’s position usually facilitates breathing. If breathing does not begin, an Ambu bag is used.

Neonatal Hypoxia

Neonatal hypoxia is inadequate oxygenation at the cellular level in a newborn infant. A deficiency of oxygen in the arterial blood is known as hypoxemia. The degree of hypoxemia present can be detected by a noninvasive pulse oximetry reading. Pulse oximetry is defined as the measure of oxygen on the hemoglobin in the circulating blood divided by the oxygen capacity of the hemoglobin. A pulse oximeter saturation level of 92% or higher is normal (Skill 13.1). There must be at least 5 g/dL of desaturated hemoglobin (unoxygenated blood) to produce clinical cyanosis. Therefore the severely anemic infant may have severe hypoxia yet not manifest clinical cyanosis. If the hemoglobin present is an abnormal fetal hemoglobin, hypoxia can be present even when the pulse oximeter shows a normal reading because fetal hemoglobin does not readily release oxygen to the tissues and end organs (Rohan and Golombek, 2009).

Some pulse oximeters can also noninvasively measure the transcutaneous hemoglobin level and provide an accurate oxygen saturation level. Others can display oxygen saturation and total hemoglobin simultaneously. The devices can also be set to display the respiratory rate and the carboxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin levels, with additional sensors.

Sepsis

Sepsis is a generalized infection of the bloodstream. Preterm newborns are at risk for developing this complication because of the immaturity of many body systems. The liver of the preterm infant is immature and forms antibodies poorly. Body enzymes are inefficient because of the abbreviated stay in the uterus. There is little or no immunity received from the mother, and stores of nutrients, vitamins, and iron are insufficient. There may be no local signs of infection, which also hinders diagnosis. Some signs of sepsis include a low temperature, lethargy or irritability, poor feeding, and respiratory distress. Maternal infection and complications during labor can also predispose the preterm infant to sepsis.

Treatment involves administration of intravenous antimicrobials, maintenance of warmth and nutrition, and close monitoring of vital signs, including blood pressure. Keeping nursing care as organized as possible will help conserve energy. An incubator separates the infant from other infants in the unit and facilitates close observation. Maintenance of strict standard precautions is essential.

Poor Control of Body Temperature

Keeping the preterm infant warm is a nursing challenge. Heat loss in the preterm infant results from the following factors:

- • The preterm infant has a lack of brown fat, which is the body’s insulation.

- • There is excessive heat loss by radiation from a surface area that is large in proportion to body weight. The large surface area of the head predisposes the infant to heat loss.

- • The heat-regulating center of the brain is immature.

- • The sweat glands are not functioning to capacity.

- • The preterm infant is inactive, has muscles that are weak and less resistant to cold, and cannot shiver.

- • The posture of the preterm infant’s extremities is one of leg extension. This increases the surface area exposed to the environment and increases heat loss.

- • Metabolism is high, and the preterm infant is prone to low blood glucose levels (hypoglycemia).

These and other factors make the preterm newborn vulnerable to cold stress, which increases the need for oxygen and glucose. Early detection can prevent complications.

Nursing Care

The infant’s skin temperature will decrease before the core temperature falls. Therefore a skin probe is used to monitor the temperature of preterm infants. The skin probe is placed in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Care should be taken to ensure that the probe is not directly over a bony prominence, in the line of cool oxygen input, or under a diaper.

The infant is placed under a radiant warmer or in an incubator to maintain a warm environment. The temperature of the incubator is adjusted so that the infant’s body temperature is at an optimal level (36.2° to 37°C [97.1° to 98.6 °F]).

Hypoglycemia and Hypocalcemia

Hypoglycemia (hypo, “less than,” and glycemia, “sugar in the blood”) is common among preterm infants. They have not remained in the uterus long enough to acquire sufficient stores of glycogen and fat. This condition is aggravated by the need for increased glycogen in the brain, the heart, and other tissues as a result of asphyxia, sepsis, RDS, unstable body temperature, and similar conditions. Any condition that increases energy requirements places more stress on these already deficient stores. Plasma glucose levels lower than 40 mg/dL in a term infant and lower than 30 mg/dL in a preterm infant indicate hypoglycemia.

The brain needs a steady supply of glucose, and hypoglycemia must be anticipated and treated promptly. Any condition that increases metabolism increases glucose needs. Preterm infants may be too weak to suck and swallow formula and often require gavage or parenteral feedings to supply their need of 120 to 150 kcal/kg/day. Nursing responsibilities include frequent glucose monitoring and nasogastric or parenteral feedings.

Hypocalcemia (hypo, “below,” and calcemia, “calcium in the blood”) is also seen in preterm and sick newborns. Calcium is transported across the placenta throughout pregnancy, but in greater amounts during the third trimester. Early birth can result in infants with lower serum calcium levels.

In early hypocalcemia, the parathyroid fails to respond to the preterm infant’s low calcium levels. Infants stressed by hypoxia or birth trauma or who are receiving sodium bicarbonate are at high risk for this problem. Infants born to mothers who are diabetic or who have had a low vitamin D intake are also at risk for developing early hypocalcemia.

Late hypocalcemia usually occurs about age 1 week in newborn or preterm infants who are fed cow’s milk. Cow’s milk increases serum phosphate levels, which cause calcium levels to fall.

Administering intravenous calcium gluconate is the treatment for hypocalcemia. During intravenous therapy, the nurse should monitor the infant for bradycardia. Adding calcium lactate powder to the formula also lowers phosphate levels. (Calcium lactate tablets are insoluble in milk and must not be used.) When calcium lactate powder is slowly discontinued from the formula, the nurse should again monitor the infant for signs of neonatal tetany.

Increased Tendency to Bleed

Preterm infants are more prone to bleeding than full-term infants because their blood is deficient in prothrombin, a factor of the clotting mechanism. Fragile capillaries of the head are particularly susceptible to injury during delivery, causing intracranial hemorrhage. Ultrasonography is helpful in detecting this problem. The nurse should monitor the neurological status of the infant and report bulging fontanelles, lethargy, poor feeding, and seizures. The bed should be in a slight Fowler’s position, and unnecessary stimulation that can cause increased intracerebral pressure should be avoided.

Retinopathy of Prematurity

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a disorder of the developing retina in premature infants that can lead to blindness. The condition was formerly termed retrolental fibroplasia, but the term ROP is currently used because it is more precise. It is the leading cause of blindness in newborns weighing less than 1500 g (3.3 lb). The condition can be caused by many factors, but premature infants are more commonly at risk because their immature retinas are incompletely vascularized at birth.

After birth, often accompanied by high levels of oxygen required for the infant’s survival, the retina completes an abnormal vascularization process that causes fibrous tissue to form behind the lens of each eye, resulting in blindness and retinal detachment (Olitsky and Marsh, 2020). Full-term infants who have fully developed vascular systems in the retina at birth are usually not affected, but infants with an unstable course should be monitored for ROP. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) standards recommend routine retinal examinations by certified ophthalmologists in the NICU for infants with a birth weight between 1500 and 2000 g or a gestational age less than 30 weeks. Examination at 4 weeks of age and at proper intervals for follow-up can result in early detection and prompt treatment. Retinal ablative therapy using laser photocoagulation of the fibrous tissue, or intravitreal injection of bevacizumab, has been used with success in preventing blindness (Olitsky and Marsh, 2020). Follow-up for other eye problems, such as strabismus, refractive errors, or cataracts, should be provided within 4 to 6 months after discharge from the NICU. The nurse must teach the parents the importance of follow-up care.

Prevention of preterm births and the problems that beset preterm infants is the key to preventing ROP. Careful monitoring of oxygen saturation in high-risk infants with a pulse oximeter continues to be a priority in the nursery (see Skill 13.1). It is the level of oxygen in the blood, rather than the amount of oxygen received, that is of importance in oxygen therapy. There is no “safe level” of oxygen. Infants must be provided with the level of oxygen required to sustain life and prevent neurological damage. Maintaining a sufficient level of vitamin E and avoiding excessively high concentrations of oxygen are important.

Poor Nutrition

The stomach capacity of the preterm infant is small. The sphincter muscles at both ends of the stomach are immature, which contributes to regurgitation and vomiting, particularly after overfeeding. Sucking and swallowing reflexes are immature. The infant’s ability to absorb fats is poor (this includes fat-soluble vitamins). The inadequate store of nutrients in the preterm infant and the need for glucose and nutrients to promote growth and prevent brain damage contribute to the nutritional problems of the preterm infant. Parenteral or orogavage feedings are usually required until the infant is strong enough to tolerate oral feedings without compromising cardiorespiratory status. Orogavage is preferred to nasal gavage feedings because newborns are obligatory nose breathers and the nasogastric tube does take up space in the nose. Abdominal girth should be measured and bowel sounds assessed in order to detect early signs of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). Signs that indicate readiness for oral feeding include a strong gag reflex and sucking and rooting reflexes. Nipple feedings are started slowly, and some initial weight loss may be noted due to the energy expenditure of oral feedings. Placing the infant on the right side or abdomen after feeding promotes gastric emptying and reduces aspiration if vomiting occurs.

Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is an acute inflammation of the bowel that leads to bowel necrosis. Preterm newborns are particularly susceptible to NEC. Factors implicated include a diminished blood supply to the lining of the bowel wall because of hypoxia or sepsis; this causes a decrease in protective mucus and results in bacterial invasion of the delicate tissues. A source for bacterial growth occurs when the infant is fed a milk formula or hypertonic gavage feeding.

Signs of NEC include abdominal distention, bloody stools, diarrhea, and bilious vomitus. Specific nursing responsibilities include observing vital signs, maintaining infection control techniques, and carefully resuming oral fluids as ordered. Measuring the abdomen and listening for bowel sounds are also important measures. Treatment includes antimicrobials and the use of parenteral nutrition to rest the bowels. Surgical removal of the necrosed bowel may be indicated.

Immature Kidneys

Improper elimination of body wastes contributes to electrolyte imbalance and disturbed acid-base relationships. Dehydration occurs easily. Tolerance to salt is limited, and susceptibility to edema is increased.

The nurse should document the intake and output for all preterm infants. The nurse should weigh the dry diaper and subtract its weight from the infant’s wet diaper to determine the urine output. The urine output should be between 1 and 3 mL/kg/hour. The infant should be observed closely for signs of dehydration or overhydration. The nurse should document the status of the fontanelles, tissue turgor, weight, and urine output.

Jaundice

The liver of the newborn is immature, which contributes to a condition called icterus, or jaundice. Jaundice causes the skin and the whites of the eyes to assume a yellow-orange cast. The liver is unable to clear the blood of bile pigments that result from the normal postnatal destruction of red blood cells. The amount of bile pigment in the blood serum is expressed as milligrams of bilirubin per deciliter (mg/dL). The higher the blood bilirubin level is, the deeper the jaundice and the greater the risk for neurological damage. An increase of more than 5 mg/dL in 24 hours or a bilirubin level greater than 12.9 mg/dL requires careful investigation (Shaughnessy and Goyal, 2020). Physiological jaundice is normal and is discussed in Chapter 12. Pathological jaundice is more serious, occurs within 24 hours of birth, and is secondary to an abnormal condition, such as ABO-Rh incompatibility (see Chapter 13). In preterm infants, the normal rise in bilirubin levels (icterus neonatorum) is slower than in full-term infants and lasts longer, which predisposes the infant to hyperbilirubinemia (hyper, “excessive,” bilirubin, “bile,” and emia, “blood”), or excessive bilirubin levels in the blood.

There is more evidence of jaundice in infants who are breastfed. Breastmilk jaundice begins to be seen about the fourth day, when the mother’s milk supply develops. The newborn usually does well but is carefully monitored to rule out problems. In early-onset jaundice of the breastfed infant, inadequate infant suckling at the breast causes jaundice and necessitates an increase in breastfeeding. Glucose water feedings should not be offered to the infant because this practice may reduce milk intake and can serve to further increase bilirubin levels. In late-onset jaundice of the breastfed infant, the breastmilk itself may inhibit conjugation of bilirubin, and therefore formula may be substituted for 24 to 48 hours to reduce bilirubin levels. The total serum bilirubin level typically peaks 3 to 5 days after birth. The early discharge of a newborn necessitates follow-up visits within 2 days to check total serum bilirubin and to prevent the development of kernicterus.

The goals of treatment for hyperbilirubinemia are to prevent kernicterus (a serious neurological complication that can cause brain damage, which is also known as bilirubin encephalopathy) and to avoid the continued increase of bilirubin levels in the blood. The nursing care for hyperbilirubinemia consists of observing the infant’s skin, sclera, and mucous membranes for jaundice. (Blanching of the skin over bony prominences enhances the evaluation for jaundice.) Observing and reporting the progression of jaundice from the face to the abdomen and feet is important because the progression may indicate increasing bilirubin blood levels. Treatment includes monitoring and reporting bilirubin laboratory values and documenting the response of the infant to phototherapy. (See Chapter 12 and Skill 12.4 for assessing jaundice.)

Special Needs

The physician appraises the physical status of the preterm newborn at delivery. The immediate needs are to clear the infant’s airway and to provide warmth. The infant is given care for the umbilical cord and care for the eyes and is then properly identified. The infant is placed naked in an incubator and taken to the nursery. The nurse in charge receives a report on the general condition of the newborn, the type of delivery, and any complications that have occurred. Many hospitals transfer their preterm infants to special medical centers geared to care for them. The transport team is briefed by the neonatologist and is dispatched to the referring hospital. A life-support infant transport incubator that can be carried by ambulance (and sometimes helicopter) is used.

Box 13.1 lists some nursing goals for care of the preterm newborn.

Thermoregulation (Warmth)

Thermoregulation (thermo, “heat,” and regulation, “maintenance of”) involves maintaining a stable body temperature and preventing hypothermia (low temperature) and hyperthermia (high temperature). A stable body temperature is essential to the survival and management of preterm infants.

Incubator

The preterm newborn is placed in an incubator designed to provide a neutral thermal environment—temperature, air, radiating surface temperatures, and humidity are controlled to maintain the infant’s temperature within a normal range with minimal oxygen consumption required. The incubator also provides isolation and protection from infection. The top of the incubator is transparent to enable personnel to view the newborn clearly at all times. Different models include alarms to indicate overheating or a lack of circulating air, facilities for positioning, and a scale to weigh the infant without removal from the warm environment. Nurses must understand how to use the incubators available in the nurseries to which they are assigned (Fig. 13.6). They should request assistance if needed.

The infant is dressed only in a diaper. Portholes facilitate routine infant care without disturbing the atmospheric conditions in the incubator. The infant can be assessed through Plexiglas windows. Levers under the mattress can place the bed in Fowler’s or the Trendelenburg position. Openings at the head and foot of the incubator can be used to remove soiled linen using the principles of aseptic technique. The door of the incubator can be lowered to form a platform that makes the infant accessible for special treatments or tests. The nurse must make sure the door is locked in the closed position when the incubator is in use. To promote circadian rhythms, a blanket may be placed over the top of the incubator to shield the infant from environmental lights.

The temperature of the incubator is adjusted to a level that will maintain an optimal body temperature in the infant. Smaller infants may require higher incubator temperatures. The nurse records the temperature of the infant and the incubator every 2 hours. The infant’s temperature is monitored with a heat-sensitive probe that is taped to the abdomen. The probe should not be placed over a bony prominence, areas of brown fat, the extremities, or an excoriated area of the body. Temporal artery or axillary temperatures may also be taken (see Chapter 22). A relative humidity of 60% or higher is desirable. Overheating should be avoided because it increases the infant’s oxygen and caloric requirements.

Radiant Heat

Radiant heat cribs that supply overhead heat have the advantage of providing easier access to the patient while maintaining a neutral thermal environment. The use of a Plexiglas shield with the radiant warmer is not recommended because it may block infrared heat. A reflective patch should be placed over the skin temperature probe to ensure that the infant’s skin temperature reading is not affected by the infrared heat of the radiant warmer.

Nursing Care Plan 13.1 lists nursing interventions for selected nursing diagnoses pertinent to care of the preterm newborn.

Kangaroo Care (Skin-to-Skin Contact)

Kangaroo care is a method of care for preterm infants that uses skin-to-skin contact. This method of holding the infant is similar to the way a kangaroo keeps its offspring warm in its pouch (Skill 13.2). The practice began in 1979 in Bogota, Colombia, in response to a shortage of incubators and staff and is currently a popular practice in the United States. The infant, wearing only a diaper and a small cap, rests on the mother’s or father’s naked chest. The skin provides warmth and calms the child, and the contact promotes bonding. Kangaroo care has been shown to be superior to holding a blanket-wrapped infant for enhancing the stabilization of infants and promoting later development (Mehler et al., 2020). Skin-to-skin contact is an important practice in hospitals that are designated as “baby friendly.”

Nutrition

Feeding of the preterm newborn varies with gestational age and health status. The ability to coordinate breathing, sucking, and swallowing does not develop before 34 weeks of gestation. Therefore a very preterm infant may require gavage feedings (via a tube placed through the nose or mouth into the stomach). Infants weighing more than 1500 g (3.3 lb) may be able to bottle feed if a small, soft nipple with a large hole is used to minimize the energy and effort required for sucking. Human milk is ideal because the fat is absorbed readily. Breastmilk may be manually expressed by the mother and placed in a bottle for her preterm infant. If the infant is gavage fed, the tube is replaced every 3 to 7 days. Intravenous fluids may be provided to meet fluid, calorie, and electrolyte needs in small, weak preterm infants. Often the infants are fed while still in the incubator. Early initiation of feedings reduces the risk of hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and dehydration.

The nurse should observe and record bowel sounds and the passage of meconium, which indicate intestinal readiness for oral feedings. When the infant is gavage fed, the contents of the stomach should be aspirated before the feeding is started. If only mucus or air is aspirated, the feeding can be given as planned. If a residual of liquid contents is aspirated, the physician should be notified before proceeding to feed the infant. Infants older than 28 weeks of gestation usually have the digestive enzymes required for the digestion of breastmilk. Formulas designed for the term infant are not well tolerated by preterm infants because they are a burden to their kidneys and can cause central nervous system problems. Formulas designed for preterm infants are not well tolerated by infants older than 34 weeks of gestation or term infants because hypercalcemia may develop. Supplemental vitamins are usually prescribed for the preterm infant. If the infant is too premature or too ill to tolerate oral feedings, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) (intravenous infusion of lipids and nutrients) may be prescribed to meet the infant’s nutritional and growth needs. Gavage and gastrostomy tube feedings are discussed in Chapter 22.

Close Observation

The physician examines the preterm newborn and writes specific orders for treatment and nursing care. When the physician leaves the nursery, the nurse is responsible for reporting any significant changes in the infant’s condition. The experienced nurse in the preterm nursery observes and charts care and treatment in great detail. Table 13.1 lists the general observations to guide care of the preterm newborn. Sudden changes are reported immediately.

Table 13.1

Positioning and Nursing Care

In the NICU environment, with close observation, the preterm newborn can be positioned on the side or prone, with the head of the mattress slightly elevated unless contraindicated. In this position, the abdominal contents do not press against the diaphragm and impede breathing.

Positioning of the preterm infant should be compatible with the drainage of secretions and the prevention of aspiration. Propping the infant on the side or placing the infant prone can reduce respiratory effort, improve oxygenation, promote a more organized sleep pattern, and lessen physical activity that burns up energy needed for growth and development. An enclosed space, or nesting, can provide a calming, supportive environment that promotes body flexion for the preterm infant (Fig. 13.7). Infants should be gradually weaned from the prone position when the physical condition becomes stable, and they should be placed in the supine position well before discharge from the NICU.

An enclosed space bounded by small blanket rolls encircling the preterm infant provides a calming, supportive environment.

It is important to teach the parent about the importance of the “back-to-sleep” concept to prevent sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). The infant should not be left in one position for long periods because it is uncomfortable and may harm the lungs. Changing the position also prevents breakdown from pressure on the infant’s delicate skin. If such a breakdown should occur, the area is exposed to the air, and a suitable ointment is applied as prescribed by the health care provider. Alkaline-based soap, alcohol, and medicated wipes should not be used on the preterm infant’s thin and sensitive skin. Hydrocolloid adhesives or using gauze or cotton under adhesive tape is advisable.

Daily cleansing of the eyes, mouth, and diaper area, and baths two or three times weekly with the application of emollients such as Eucerin or Aquaphor, promote skin integrity (see Chapter 12 for a more extended discussion of the skin of the newborn).

Every effort should be made to maintain a quiet environment and organize nursing care so that overstimulation of the preterm infant is avoided. Blankets can be placed over the top of the incubator to reduce external stimulation and to establish a normal circadian rhythm (night-day sleep pattern), and dimmer switches on lights can encourage the infants to open their eyes and become responsive to the environment. Eye patches can be placed over the infant’s eyes to protect against the bright procedure lights. Observing the physical and behavioral responses of the preterm infant enables a developmentally appropriate care plan to be developed. The preterm infant should be awakened slowly and gently for procedures or nursing care and should be moved gently, maintaining flexion of the arms close to the midline of the infant’s body. Nonnutritive sucking is beneficial to the infant.

Some studies have shown that cobedding of twins (placing them together in one incubator) may improve their growth and development, but further research is needed to determine the risks related to the transmission of infection.

Use of Complementary Medicine in the NICU

Aroma therapy is often used in the NICU by placing an article of clothing with the mother’s natural body odor next to the newborn in the incubator (Kassity-Kritch and Jones, 2014). Other types of aroma therapy have been researched. Music therapy may also be effective in calming the infant and enhancing language development, especially if the parent sings softly to the infant. Gentle therapeutic touch and gentle massage are beneficial in many ways to the preterm infant—they reduce motor activity and energy expenditure and enhance bonding with the parents.

Prognosis

In the absence of severe birth defects and complications, the growth rate of the preterm newborn nears that of the term infant by about the second year. Very-low-birth-weight infants may not catch up as fast, especially if there has been chronic illness, insufficient nutritional intake, or inadequate care taking. Additional studies are needed to determine the effects of these factors at various age levels. Parents must be prepared for relatives’ comments on the infant’s small size and slower development. In general, growth and development of the preterm infant are based on current age minus the number of weeks before term that the infant was born; for example, if born at 36 weeks of gestation, a 1-month-old infant would be at a newborn’s achievement level. This calculation ensures that no one has unrealistic expectations for the infant.

Family Reaction

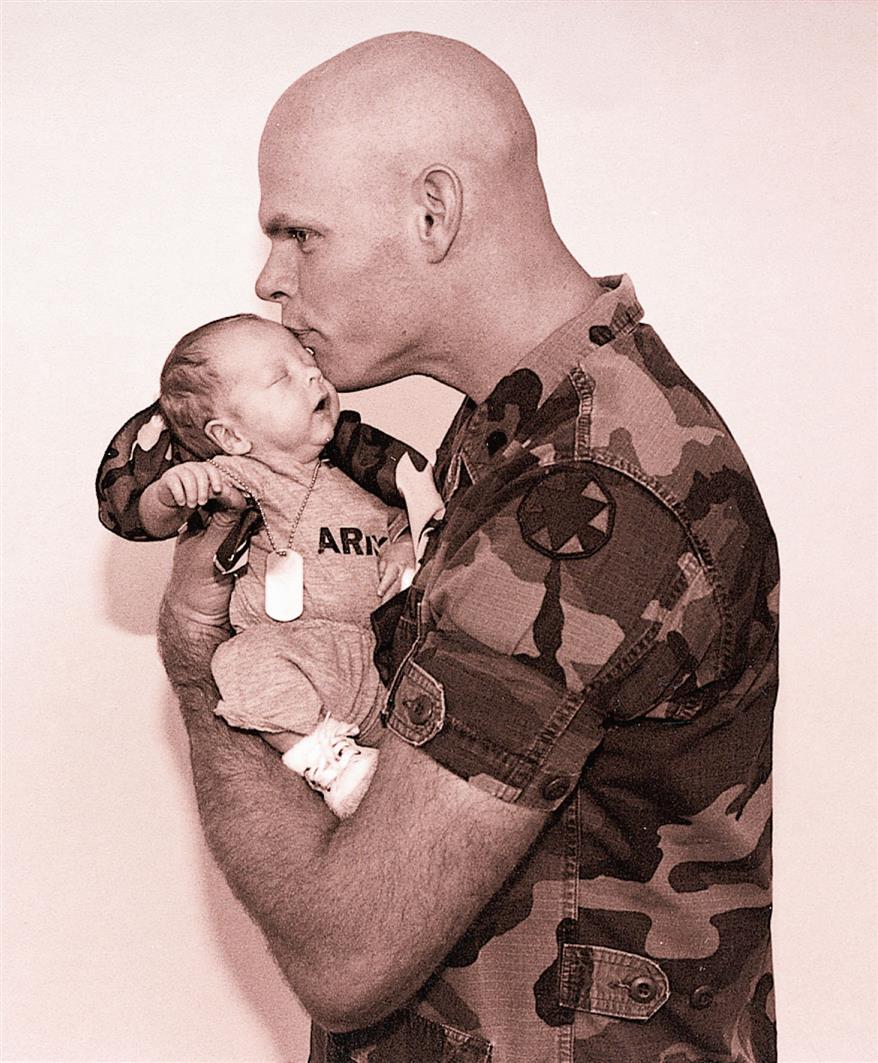

The nurse should assist the parents to cope with their responses to having a small, preterm infant. Parents need guidance throughout the infant’s hospitalization to help prepare them for this new experience. They may be disheartened by the unattractive appearance of the preterm newborn. They may believe that they are to blame for the infant’s condition. They may fear that the infant will die but may be unable to express their feelings. They need time to look at and touch the infant and begin to see the child as uniquely their own (Fig. 13.8). This touch and immediate human contact are also vital for the infant. The mother is usually concerned with her ability to care for such a small and helpless creature. When she feels ready, she may assist the nurse in diapering, bathing, feeding, and other activities. Other aspects of infant care are also stressed during this time.

Nursing care of the preterm infant includes measures to provide short periods of stimulation during the alert phase of activity. The parents can be taught to provide stimulation by using a black and white mobile, stroking gently, talking to the infant, rocking, or providing range-of-motion activity or kangaroo care. A pacifier may be used during gavage feeding to provide nonnutritive sucking. Care should be taken not to overly stimulate or tire the infant. There should be minimal stimulation during feeding to enable the infant to concentrate energy on the sucking and swallowing process. Mild stimulation and interaction with parents should be provided between feedings.

The nurse should collaborate with pediatricians, social workers, nutritionists, psychologists, and staff from other disciplines to plan and coordinate follow-up care of the preterm infant after discharge. Often a mother is discharged without her infant. This is difficult for the entire family and makes attachment and bonding more complicated. The nurse encourages the family to keep in touch by telephone and by visits. Parents can help siblings to accept the infant by addressing the child by name, sharing news of progress, taking pictures of the infant, and encouraging communication by means of drawings and cards. Listening to what siblings are saying provides information for discussion.

The Postterm Newborn

The newborn is considered postterm if the pregnancy goes beyond 42 weeks. Postmaturity refers to the infant showing characteristics of the postmature syndrome. Identification of infants who are not tolerating the extra time in the uterus is the major goal of treatment. Death of the postterm infant is uncommon today because of early detection and intervention. The cause of postmaturity is not yet clear; however, it is known that the placenta does not function adequately as it ages, which could result in fetal distress. The mortality rate of late infants is higher than that of newborns delivered at term. Morbidity rates are also higher. After the infant survives delivery, the risks are fewer.

The late birth is a psychological strain on the mother, the father, and other members of the family, who are eagerly awaiting the arrival of the child. The nurse encourages parents to verbalize their feelings and concerns about the delay. Very large newborns, such as those of diabetic mothers, are not necessarily postmature, but are larger than normal because of rapid, abnormal growth before delivery.

The following problems are associated with postmaturity:

- • Asphyxia, caused by chronic hypoxia while in the uterus because of a deteriorated placenta

- • Meconium aspiration: hypoxia and distress may cause relaxation of the anal sphincter, and meconium can be aspirated into the fetal lungs

- • Poor nutritional status; depleted glycogen reserves cause hypoglycemia

- • Increase in red blood cell production (polycythemia) because of intrauterine hypoxia

- • Difficult delivery because of increased size of the infant

- • Birth defects

- • Seizures as a result of the hypoxic state

Physical Characteristics

The postterm infant is long and thin and looks as though weight has been lost. The skin is loose, especially about the thighs and buttocks. There is little lanugo (downy hair) or vernix caseosa. The loss of the cheese-like vernix caseosa leaves the skin dry; it cracks, peels, and is almost like parchment in texture. The nails are long and may be stained with meconium. The infant has a thick head of hair and looks alert.

Nursing Care

Labor induction or cesarean deliveries are commonly performed if testing determines that the pregnancy is past 42 weeks or if there are signs of fetal distress or maternal risk. Many postterm infants suffer few adverse effects from the delay, but they still require careful observation in the nursery. Nursing care involves observing for respiratory distress (usually because of aspiration of meconium-stained amniotic fluid), hypoglycemia (caused by depleted glycogen stores), and hyperbilirubinemia (as a result of polycythemia). The infant may be placed in an incubator because fat stores have been used in utero for nourishment and the infant is vulnerable to cold stress.

Transporting the High-Risk Newborn

Transportation of the high-risk newborn to a regional neonatal center requires the organization and expertise of a special team. A nurse and sometimes a physician accompany the infant unless specialists in emergency medical transport are part of the transport team. Stabilization of the infant before discharge is important. Baseline data, such as vital signs and blood work (blood gases and glucose levels), are obtained. The infant is weighed if this is not contraindicated. Copies of all records are made, including the infant’s record, the mother’s prenatal history and delivery, and pertinent admission data. A transport incubator is provided for warmth, and the batteries are kept fully charged.

The nurse is responsible for placing an identification band on the infant before transport and for verifying the identification name and number with the mother’s identification band. The mother should be reassured that the identification will stay with the infant. The parents should be given the name and location of the receiving hospital and the name and telephone number of a physician to contact for follow-up information and visits.

Parents are shown the newborn before departure. If the mother is unable to hold the infant because of the baby’s condition, the incubator is wheeled to her bedside for her observation. A picture is taken and given to the parents. On occasion, a mother is unable to see her infant because of her own unstable condition. Such situations require special empathy from nursing personnel. After the infant has safely reached the destination, the parents are contacted by telephone. It is also thoughtful for the receiving hospital personnel to provide feedback to the transport team so that they may enjoy hearing the results of their efforts.

Discharge of the High-Risk (Preterm Birth) Newborn

Discharge planning begins at birth. The parents will need to demonstrate and practice routine and/or specialized care. Visits by the nurse to assess home care and to provide additional support are valuable. Continued medical supervision is important. The nurse stresses the importance of well-baby examinations, immunizations, and prevention of infection. Good prenatal care for subsequent pregnancies is emphasized (especially after a preterm birth because the mother is at high risk for future preterm births).

Parents are often anxious about taking their high-risk newborn home. The nurse must familiarize them with the newborn’s care. The newborn’s behavioral patterns are discussed, and realistic expectations concerning the preterm infant’s catch-up development are reviewed. Communication is maintained, with “warm lines” and “hot lines” provided to parents. The social services department may be of help in ensuring that the home environment is satisfactory and that special needs can be met. Support group referrals are given to parents, and newborn cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) techniques are reviewed.

Get Ready for the Next-Generation NCLEX® Examination!

Key Points

- • Every week in utero up to 39 weeks’ gestation is important for optimal fetal development.

- • Early identification of the high-risk fetus facilitates treatment and nursing care.

- • Studies indicate that there is a relationship between prematurity and poverty, smoking, alcohol consumption, narcotics use, and lack of prenatal care.

- • Preterm infants have poor muscle tone and less subcutaneous fat but more vernix and lanugo than full-term infants.

- • The preterm infant is observed for jaundice, low oxygen saturation levels, and unstable vital signs. The intake and output of all preterm infants is monitored.

- • The care of preterm infants is organized and “clustered” to minimize handling and stimulation.

- • Blanket rolls are used to provide an enclosed space for preterm infants.

- • Nurses support parents and encourage participation in care.

- • Respiratory distress syndrome has a high mortality rate, and it may precipitate long-term effects.

- • Hypoxia is lack of oxygen on the cellular level, and hypoxemia is decreased oxygen in the circulating blood.

- • Problems associated with prematurity include asphyxia, meconium aspiration, hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hemorrhage from fragile vessels, poor resistance to infection, and inadequate nutrition.

- • Hypoglycemia is defined as a glucose level lower than 40 mg/dL in the term infant or lower than 30 mg/dL in the preterm infant.

- • Heat or thermoregulation is essential for the preterm newborn’s survival. Cold stress is to be avoided.

- • Nursing goals in caring for the preterm newborn are improving respirations, maintaining body heat, conserving the infant’s energy, preventing infection, providing nutrition and hydration, providing good skin care, and supporting and encouraging the parents.

- • Kangaroo care promotes stabilization of the infant and enhances later development.

- • Retinopathy of prematurity is a disorder of the developing retina that can lead to blindness in the preterm infant.

- • The postterm newborn is born after 42 weeks of gestation and shows certain characteristics that place the infant at risk, such as hypoxia, poor nutritional stores, and polycythemia.

- • The postterm newborn has little lanugo and vernix, and the skin is dry and peeling.

Additional Learning Resources

![]() Go to your Study Guide for additional learning activities to help you master this chapter content.

Go to your Study Guide for additional learning activities to help you master this chapter content.

Go to your Evolve website (http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer) for the following learning resources:

- • Animations

- • Answer Guidelines for Critical Thinking Questions

- • Answers and Rationales for Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

- • Glossary with English and Spanish pronunciations

- • Interactive Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

- • Patient Teaching Plans in English and Spanish

- • Skills Performance Checklists

- • Video clips and more!

Online Resources

Online Resources

- • March of Dimes: https://marchofdimes.org

- • Premature birth: https://www.mayoclinic.com/health/premature-birth/DS00137

- • Premature birth complications: https://americanpregnancy.org/healthy-pregnancy/labor-and-birth/premature-birth-complications/

Clinical Judgment and Next-Generation NCLEX® Examination-Style Questions

- 1. Which of the following observations of a preterm neonate would indicate the presence of respiratory distress? (Select all that apply.)

- 2. The nursing observations of a preterm newborn are noted to include abdominal distention, bloody stools, diarrhea, and bilious vomitous. This is most likely indicative of _#_1__, and nursing responsibilities would include _#_2__.

Options for #1 Options for #2 Retinopathy Palpation of fontanelles Sepsis Measurement of abdomen and listening for bowel sounds Necrotizing enterocolitis Monitoring oxygen saturation levels - 3. An infant is born at 43 weeks’ gestation. The nurse should monitor the infant for common problems, such as (select all that apply):

- 4. The nurse observes that a preterm infant has a pulse rate of 96 and a pulse oximetry reading of 89%. The first action of the nurse should be the following:

- 5. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the NICU is best accomplished by:

- a. placing a sweet-smelling room deodorizer in the room that has a calming effect.

- b. using baby oil on the infant’s skin.

- c. placing an article of the mother’s clothing in the infant’s crib.

- d. using gentle touch to calm the infant.

A newborn is delivered spontaneously at 36 weeks. The infant weighed 1588 g (3.8 lb) at birth. When the infant presented with an episode of apnea associated with a heart rate of 108 beats/minute, an apnea monitor was applied. - 6. Indicate which of the nursing actions from the choices below should fill in each blank in the following sentences.

As the initial, priority intervention, the nurse would ____________. If voluntary respirations were not reestablished, the nurse would then __________________.

Nursing Interventions: