The Child with a Musculoskeletal Condition

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer.

- 1. Define each key term listed.

- 2. Discuss the musculoskeletal differences between the child and adult and how they influence orthopedic treatment and nursing care.

- 3. Demonstrate an understanding of age-specific changes that occur in the musculoskeletal system during growth and development.

- 4. Describe the management of soft tissue injuries.

- 5. Discuss the types of fractures commonly seen in children and their effect on growth and development.

- 6. Differentiate between Buck’s extension and Russell traction.

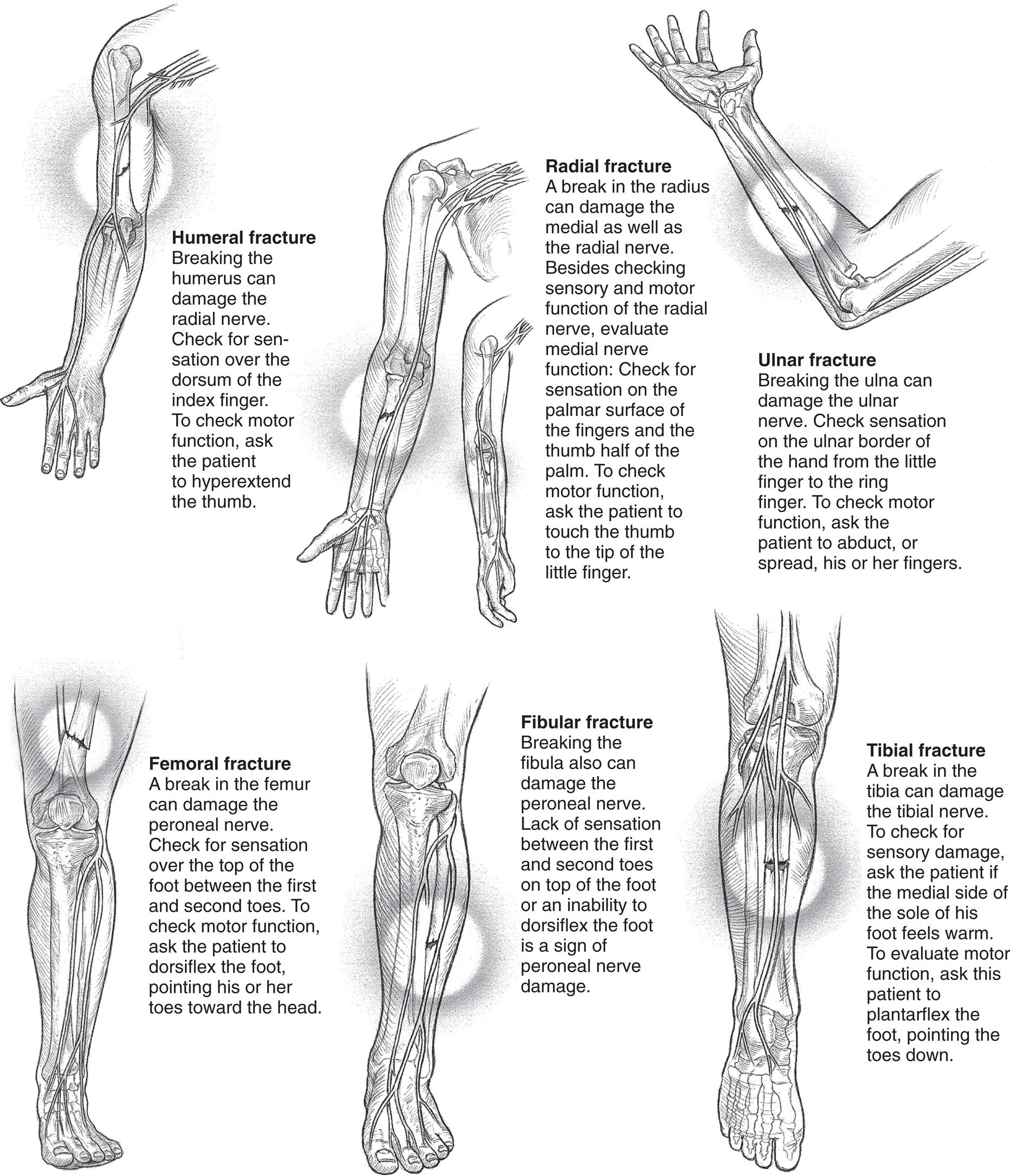

- 7. Describe a neurovascular check.

- 8. Compile a nursing care plan for the child who is immobilized by traction.

- 9. Discuss the nursing care of a child in a cast.

- 10. List two symptoms of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy.

- 11. Describe the symptoms, treatment, and nursing care for the child with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease.

- 12. Describe two topics of discussion applicable at discharge for the child with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

- 13. Describe three nursing care measures required to maintain skin integrity for an adolescent child in a cast or brace for scoliosis.

- 14. Describe three types of child abuse.

- 15. Identify symptoms of abuse and neglect in children.

- 16. State two cultural or medical practices that may be misinterpreted as child abuse.

Key Terms

contusion (kŏn-TŪ-zhŭn, p. 574)

epiphysis (ĕ-PĬF-ă-sĭs, p. 575)

genu valgum (JĒ-nū VĂL-găm, p. 574)

genu varum (JĒ-nū VĂR-ăm, p. 574)

hematoma (hē-mă-TŌ-mă, p. 574)

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (p. 584)

slipped femoral capital epiphysis (p. 584)

Musculoskeletal System

The musculoskeletal system supports the body and provides for movement. The muscular and skeletal systems work together to enable a person to sit, stand, walk, and remain upright. In addition, muscles move air into and out of the lungs, blood through vessels, and food through the digestive tract. They also produce heat, which aids in numerous body chemical reactions. Bones act as levers and provide support. Red blood cells are produced in the bone marrow, and minerals such as calcium and phosphorus are also stored there.

The musculoskeletal system arises from the mesoderm in the embryo. A great portion of skeletal growth occurs between the fourth and eighth weeks of fetal life. As the limbs elongate before birth, muscle masses form in the extremities. The Ballard scoring system (see Fig. 13.2) is one measure of assessing neuromuscular maturity at birth. Testing various reflexes is another.

Locomotion develops gradually and in an orderly manner in the growing child. A marked deceleration of growth is always a signal for investigation.

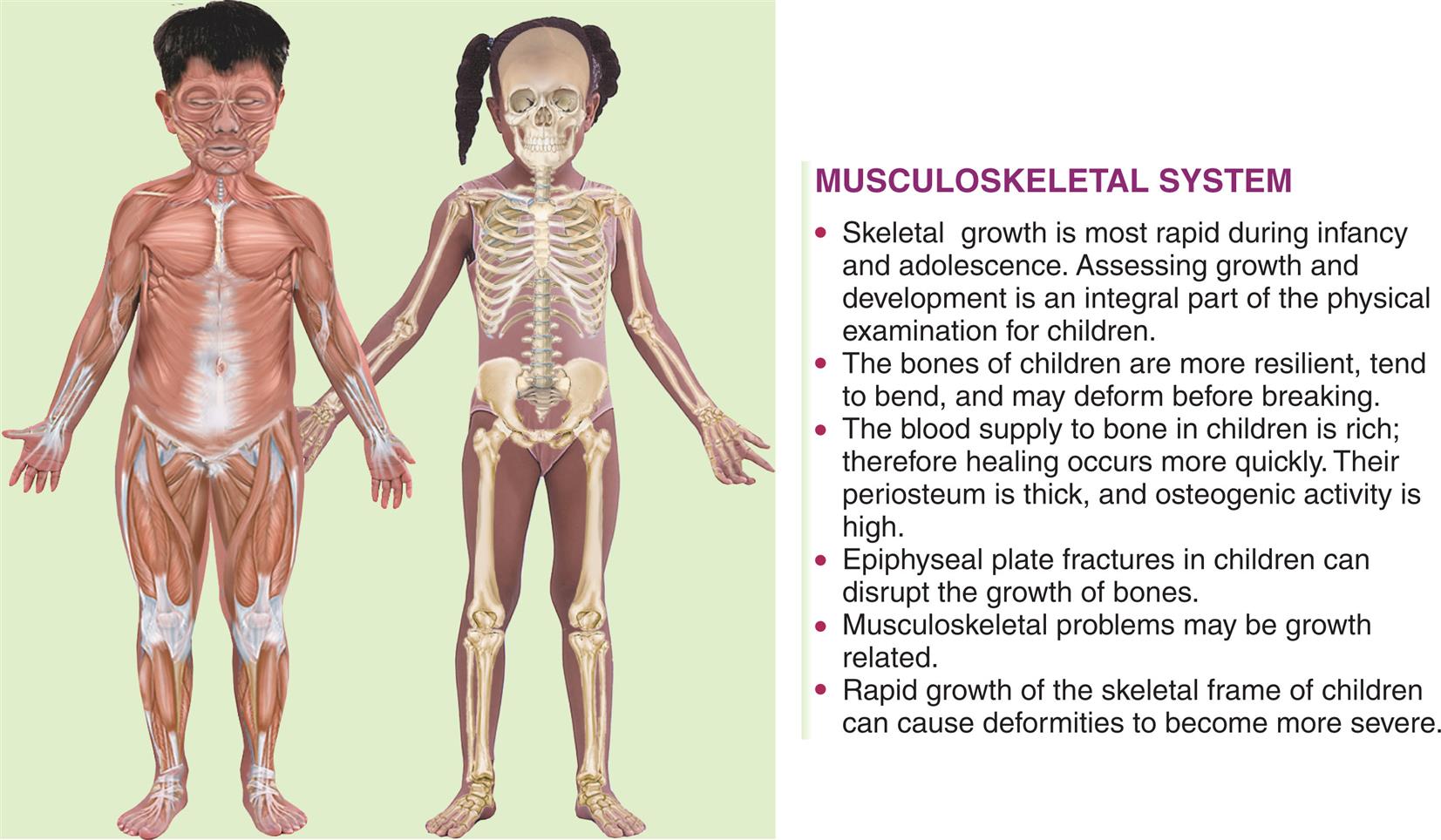

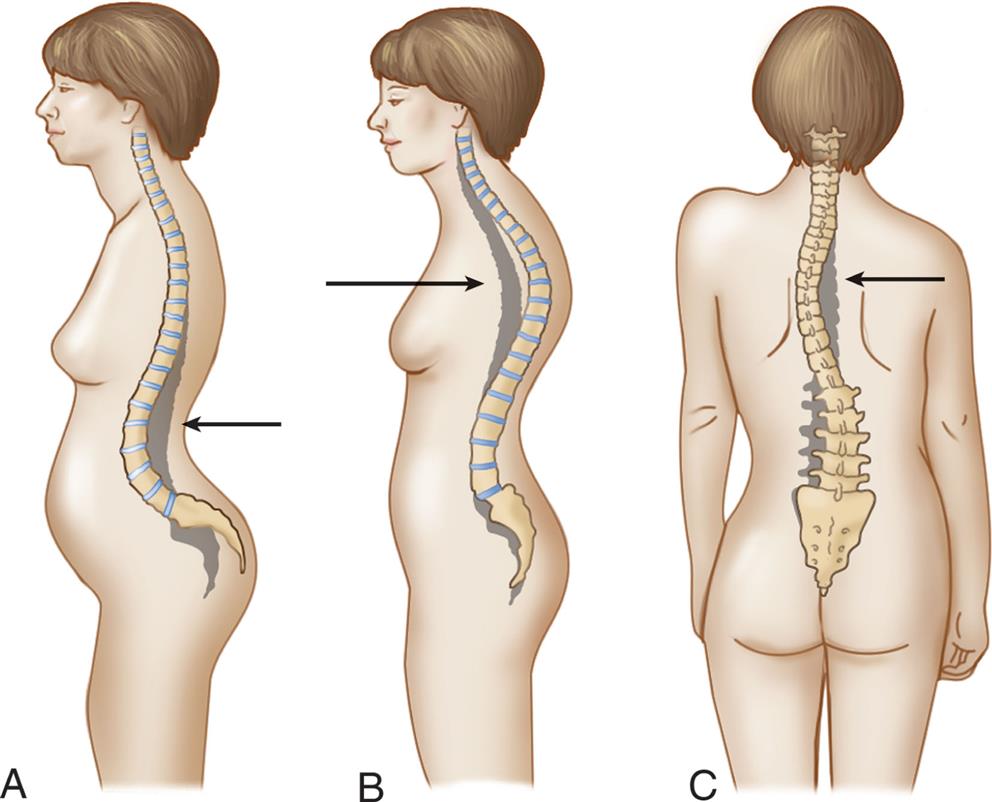

Musculoskeletal System: Differences Between the Child and the Adult

The pediatric skeletal system differs from the adult skeletal system in that bone is not completely ossified, epiphyses are present, and the periosteum is thicker and produces callus more rapidly than in the adult. The lower mineral content of the child’s bone and its greater porosity increase the bone’s strength. However, rotational or angular forces can stress ligaments that insert at the epiphyseal area of the bone, and injury to the epiphysis can affect bone growth. Because of the presence of the epiphysis and hyperemia caused by the trauma, bone overgrowth is common in healing fractures of children younger than 10 years of age. Therefore exact alignment in the reduction of the fracture is not necessary in children under 10 years of age, as bone overgrowth and growth acceleration often occurs for 6 months to a year following the injury. Fractures at or near the growth plate of the bone requires careful treatment and follow-up (Baldwin et al., 2020). At birth, the thoracic and sacral areas of the child’s spine are convex curves. When the child sits and stands, these curves must change to be concave or kyphosis or lordosis will result. Fig. 24.1 describes some differences between the child’s and the adult’s skeletal and muscular systems. Skeletal maturity and chronological age often differ.

Illustration shows skeletal of little boy and girl. Text under the heading of musculoskeletal system reads as follows: • Skeletal growth is most rapid during infancy and adolescence. Assessing growth and development is an integral part of the physical examination for children. • The bones of children are more resilient, tend to bend, and may deform before breaking. • The blood supply to bone in children is rich; therefore hearing occurs more quickly. Their periosteum is thick, and ostogenic activity is high. • Epiphyseal plate fractures in children can disrupt the growth of bones. • Musculoskeletal problems may be growth related. • Rapid growth of the skeletal frame of children can cause deformities to become more severe.

Observation and Assessment of the Musculoskeletal System in the Growing Child

To assess the musculoskeletal system of the growing child and to identify deviations, the nurse must have a basic understanding of the effect of growth, neurological development, and motor milestones at various ages. The newborn hip has limited internal rotation range of motion (ROM). The legs are maintained in a flexed position, and the lower leg has an internal rotation (internal tibial torsion) caused by the effects of uterine positioning; this can last 4 to 6 months. The general curvature of the newborn spine is a C shape from the thoracic to the pelvic level; it changes with the mastery of motor skills to a double S curve in childhood (see Fig. 17.1). The newborn’s feet normally turn inward (varus) or outward (valgus), but the turning-in self-corrects when the sole of the foot is stroked. The toddler’s feet appear flat because of the presence of a fat pad at the arch. Any delay in neurological development can cause a delay in the mastery of motor skills, which can alter skeletal growth.

Assessment of the musculoskeletal system includes observation, palpation, ROM, and gait assessment in children who can walk. Children who do not walk independently by 18 months of age have a serious delay and should be referred to a health care provider for follow-up.

Observation of Gait

A gait is a characteristic manner of walking. The toddler who begins to walk has a wide, unstable gait. The arms do not swing with the walking motion. By 18 months of age the wide base narrows and the walk is more stable. By 4 years of age the child can hop on one foot, and arm swings occur with walking. By 6 years of age, the gait resembles the adult walk with equal stride lengths and associated arm swing. The trunk is centered over the legs, and movement is symmetrical. When a child favors one side, pain may be present. Toe walking after 3 years of age can indicate a muscle problem.

In most cases, excessive in-toeing, or pointing of the toe inward, will resolve by 4 years of age. These children trip and fall easily. Teaching proper sitting and body mechanics is the treatment of choice. Participation in ballet classes and in-line skating will enhance hip flexibility. If the problem does not resolve, a brace may be prescribed. Failure to treat can result in hip, knee, or back problems in adulthood.

Young children appear bowlegged (genu varum) or knock-kneed (genu valgum), with the knees turned inward until 5 years of age. Bowing is seldom pathological. The ligaments that support the arch are not mature before 6 years of age, and therefore the child may appear to have flat feet. If the condition interferes with walking, an orthotic appliance can be prescribed for the child to wear inside the shoes. When the flat foot is painful, a referral for follow-up examination should be initiated. The role of the nurse is to reassure parents that unless there is associated pain or a problem with motor or nerve functions, many minor abnormal-appearing alignments will spontaneously resolve with activity.

Observation of Muscle Tone

The nurse should assess symmetry of movement and the strength and contour of the body and extremities. Having the child push away the examiner’s hand with his or her foot or hand can test the strength of the extremities.

Neurological Examination

A neurological assessment is a vital part of a comprehensive musculoskeletal examination. An assessment of reflexes, a sensory assessment, and the presence or absence of spasms should be noted.

Diagnostic Tests and Treatments

Radiographic Studies

Radiographs (x-ray films) are taken to confirm a suspected pathological condition, and the affected area is compared with the unaffected area.

Bone Scans

Bone scans are helpful in identifying pathological conditions that may not clearly be seen on a routine x-ray study, such as septic arthritis or tumors.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) provides a cross-sectional picture of the bone and its relationship to other structures within the area of examination.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) does not involve harmful radiation. MRIs produce detailed pictures of the brain, spinal cord, and soft tissue lesions, including a slipped femoral epiphysis.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound does not involve harmful radiation. It is used to rule out foreign bodies in soft tissues, joint effusions, and developmental dysplasia of the hip.

Laboratory Tests and Treatments

A complete blood count (CBC) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may rule out septic arthritis or osteomyelitis. Rheumatoid factor (RF) may help diagnose rheumatological disorders.

A thorough history is necessary to determine the basis for musculoskeletal problems, which are often insidious. The nurse determines the history of the injury; the location of pain; when symptoms started; any weakness, numbness, or loss of function in an extremity; and whether the problem is affecting the child’s daily activities. An arthroscopy may be performed on adolescents with sports injuries. The health care provider is able to look inside the joint (usually the knee or shoulder) to determine the extent of injury. The area is inspected, foreign particles are removed, or repairs are made to the torn menisci. A bone biopsy may show a malignancy. Muscle biopsy may detect muscular dystrophy.

Traction, casting, splints, or surgery are used in accordance with the patient’s needs. Traction is no longer a popular method of routine long-term treatment because of the various complications associated with long-term immobilization. However, traction is often used to immobilize a fracture until surgery can be performed and therefore the principles of traction and complications related to traction are included in this text. Three types of skin traction are often used for the lower extremities of children: Bryant’s traction, Buck’s extension, and Russell traction. Children with musculoskeletal disorders who are treated with traction may require lengthy hospitalization. Immobility causes a deceleration in body metabolism. Nursing interventions focus on maintaining body functions. ROM exercises and the use of a trapeze prevent muscle atrophy. Foods high in roughage stimulate the digestive tract and prevent constipation. Respiratory exercises prevent pneumonia. These and other measures can prevent complications that can lengthen hospitalization for the child. (Clubfoot, congenital hip dysplasia, and spica casts are discussed in Chapter 14. Rickets is discussed in Chapter 28.)

Pediatric Trauma

Soft Tissue Injuries

Soft tissue injuries usually accompany traumatic fractures in the child at play or the adolescent involved in sports activities and include the following:

- • Contusion: A tearing of subcutaneous tissue resulting in hemorrhage, edema, and pain. The escape of blood into the soft tissue is referred to as a hematoma, or a “black-and-blue mark.”

- • Sprain: When the ligament is torn or stretched away from the bone at the point of trauma, there may be resulting damage to blood vessels, muscles, and nerves. Swelling, disability, and pain are major signs of a sprain.

- • Strain: A microscopic tear to the muscle or tendon that occurs over time and results in edema and pain.

Treatment of Soft Tissue Injuries

Soft tissue injuries should be treated immediately to limit damage from edema and bleeding. A cold pack and elastic wrap will reduce edema and bleeding and relieve pain, and they should be applied at alternating 30-minute intervals. (After a 30-minute period, ischemia can occur and impede the tissue perfusion.) Elevating the extremity above heart level reduces edema. When an elastic bandage is used for compression, a priority nursing responsibility is to perform frequent neurovascular checks to ensure adequate tissue perfusion.

Prevention of Pediatric Trauma

Accidents are common in childhood, but much can be done to prevent morbidity and mortality. Parents are responsible for maintaining a safe environment for their children. Nurses are responsible for educating parents and schoolteachers about how to prevent accidental injury and maintain a safe environment.

The proper use of pedestrian safety practices, car seat restraints, bicycle helmets and other athletic protective gear, pool fences, window bars, deadbolt locks, and locks on cabinets can prevent many injuries to children. Pediatric trauma can cause permanent disability or premature death. Nursing assessment and interventions can assist the injured child toward recovery. The nurse also has a community responsibility to support legislation that would maintain safe environments for children.

Traumatic Fractures

Pathophysiology

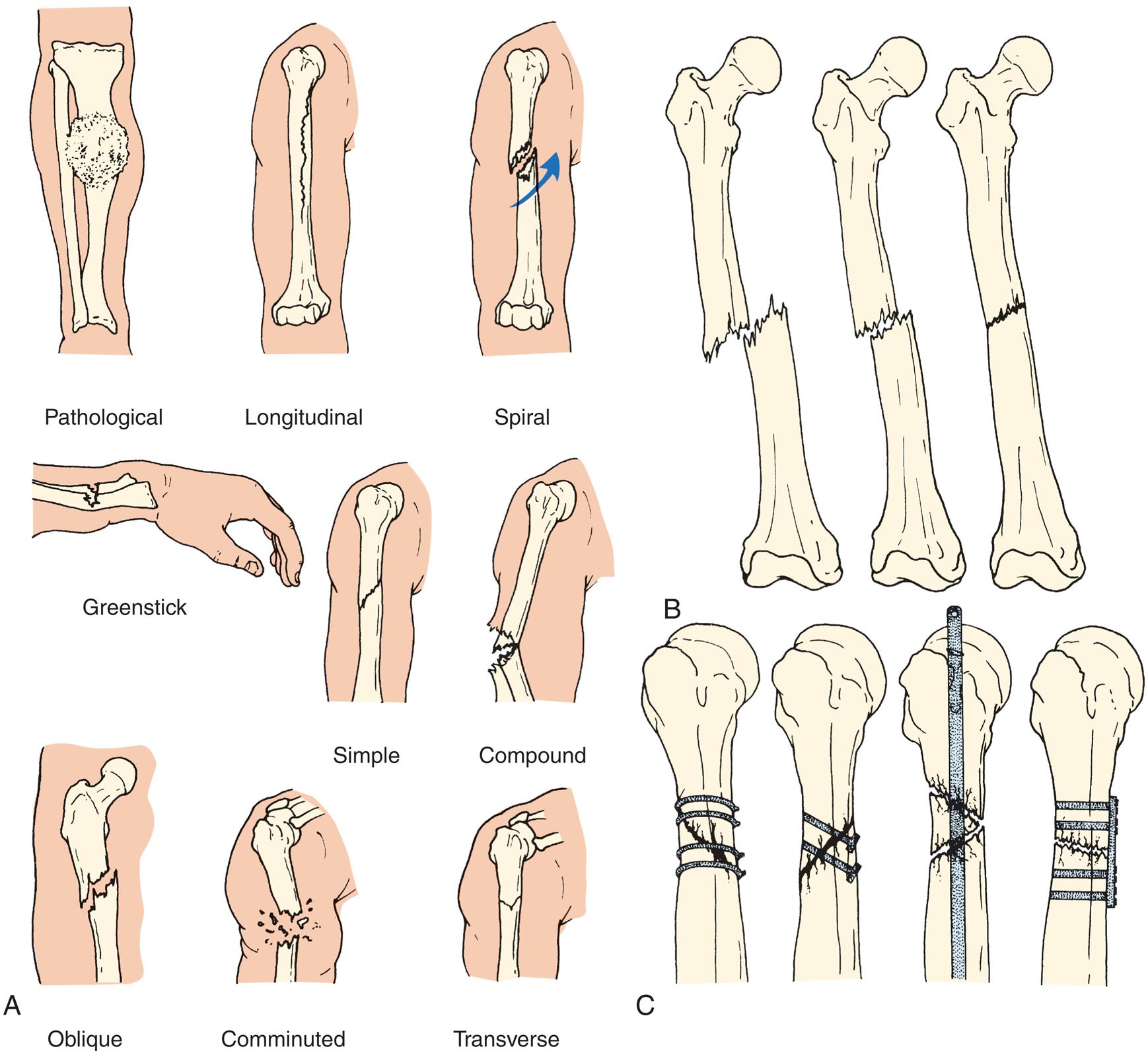

A fracture is a break in a bone and is usually caused by accidents. It is characterized by pain, tenderness on movement, and swelling. Discoloration, limited movement, and numbness may also occur. In a simple fracture, the bone is broken but the skin over the area is not. In a compound fracture, a wound in the skin accompanies the broken bone and there is an added danger of infection. A greenstick fracture is an incomplete fracture in which one side of the bone is broken and the other is bent. This type of fracture is common in children because their bones are soft, flexible, and more likely to splinter. In a complete fracture, the bone is entirely broken across its width. Fig. 24.2 illustrates various types of fractures. When an x-ray film shows multiple fractures at various stages of healing, child abuse should be suspected.

A) A series of illustrations shows types of fractures as follows: Pathological, longitudinal, spiral, greenstick, simple, compound, oblique, comminuted, and transverse. B) A series of three bones shows partial healing of fracture. C) Four illustration of bones with fractured sites fastened using plates, screws, and stitches.

A fracture heals more rapidly in a child than it does in an adult. The child’s periosteum is stronger and thicker, and there is less stiffness on mobilization. Injury to the cartilaginous epiphysis, the growth plate found at the ends of the long bones, is serious if it happens during childhood because it may interfere with longitudinal growth. A fat embolism can occur within a few hours after fractures of the long bones or multiple fractures, when fat particles escape from the site into the circulation and lodge in the lung. Although it is more common in adults than children, the nurse must be observant for signs of hypoxia following traumatic fractures. Care of a child in a cast is discussed in Chapter 14. Casts may be made of plaster or fiberglass.

Fractures of the Femur in Early Childhood

The femur (thigh bone) is the largest and strongest bone of the body. It is one of the most prevalent serious breaks that occur during early childhood. Any fracture of the lower extremities in an infant who is not ambulatory suggests a nonaccidental injury or child abuse (Baldwin et al., 2020). A forceful twisting motion of the femur causes a spiral fracture. When the history of an injury does not correlate with x-ray findings, child abuse should be suspected, because spiral fractures can be the result of manual twisting of the extremity. The child complains of pain and tenderness when the leg is moved and he or she cannot bear weight on it. Clothes are gently removed, starting at the uninjured side and proceeding to the injured side. It may be necessary to cut the clothes; x-ray films confirm the diagnosis. Skin traction is used to reduce the fracture and keep the bones in proper alignment. A spica cast may be applied. See Chapter 14 for care of the child in a spica cast.

Treatment of Fractures with Traction

Most bone fractures are manually reduced or surgically pinned in place. Traction is avoided whenever possible because it involves long-term bed rest and resulting complications. In some countries throughout the world, and in mass casualty events, surgical intervention may not be readily available and traction is required; therefore all nurses should be familiar with the care of the patient in traction.

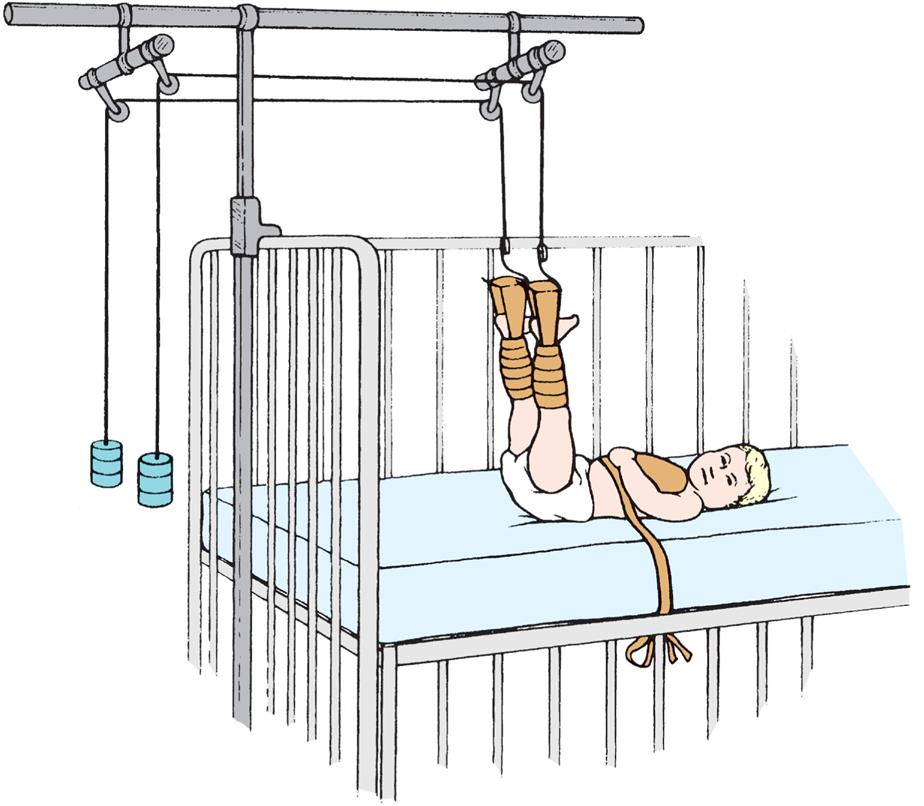

Traction in the Younger Child

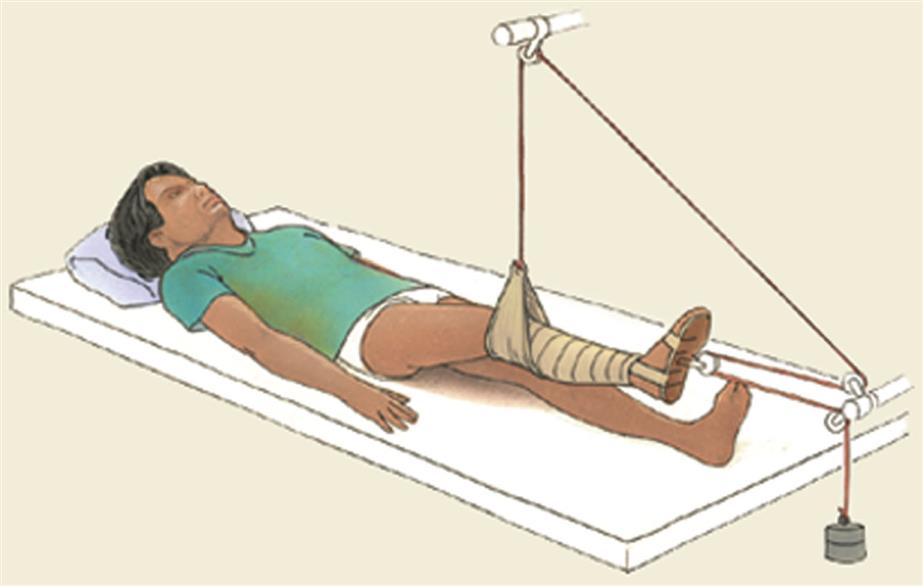

Bryant’s traction is used for treating fractures of the femur in children younger than 2 years of age or lighter than 9.09 kg to 13.64 kg (20 to 30 lb). Weights and pulleys extend the limb as in the Buck’s extension; however, the legs are suspended vertically (Fig. 24.3). The weight of the child supplies the countertraction.

Traction in the Older Child

Traction is used when the cast cannot maintain alignment of the two bone fragments. Skeletal muscles act as a splint for the fracture. Traction aligns the injured bone by the use of weights and countertraction. Immobilization is maintained until the bones fuse.

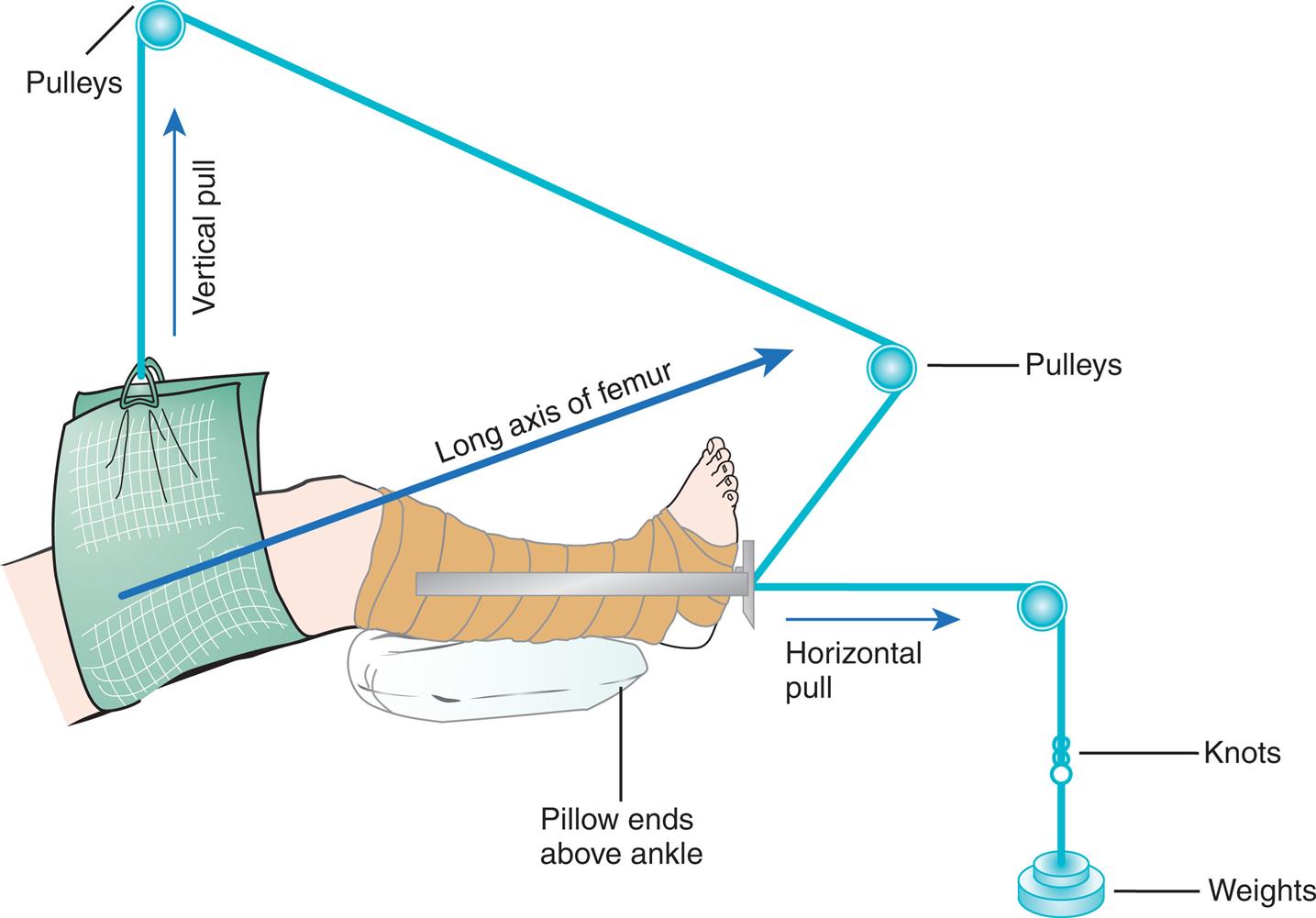

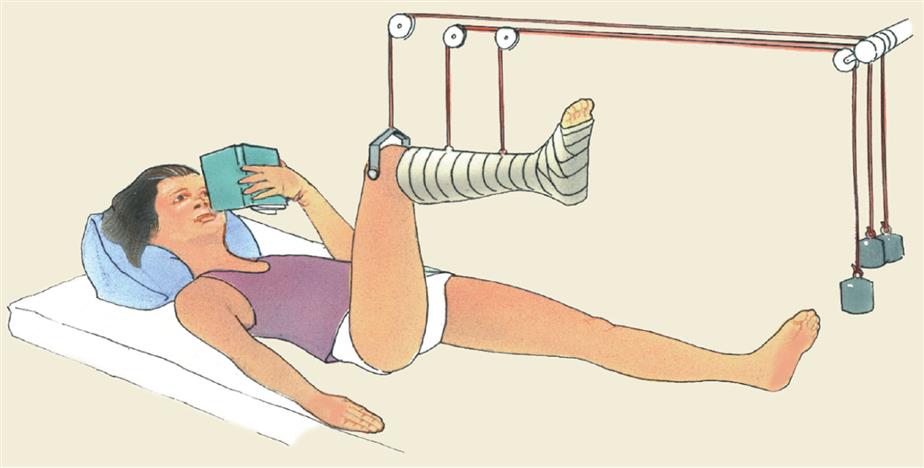

Buck skin traction (Buck’s extension) is a type of skin traction used in fractures of the femur and in hip and knee contractures. It pulls the hip and leg into extension. The child’s body supplies countertraction; therefore it is essential that the child does not slip down in bed and that the bed is not placed in high Fowler’s position. Buck’s extension is sometimes used preoperatively, either unilaterally or bilaterally, to reduce pain and muscle spasm associated with a slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Russell traction is similar to Buck’s extension. In Russell traction, however, a sling is positioned under the knee, which suspends the distal thigh above the bed (Fig. 24.4). Skin traction is applied to the lower extremity. Pull is in two directions, vertically from the knee sling and longitudinally from the footplate (Fig. 24.5). This prevents posterior subluxation of the tibia on the femur, which can occur in children who are in traction. Split Russell traction uses two sets of weights, one suspending the thigh and the other exerting a pull on the leg, with weights at the head and foot of the bed. Balanced suspension using the Thomas splint and Pearson attachments is used to treat diseases of the hip as well as fractures in older children and adolescents. It may be used both before and after surgery.

Illustration shows thigh being pulled upward by a vertical pull and pulleys. A diagonal arrow is marked long axis of femur. Lower leg has pillow ends above ankle and horizontal pull experienced using knots and weights.

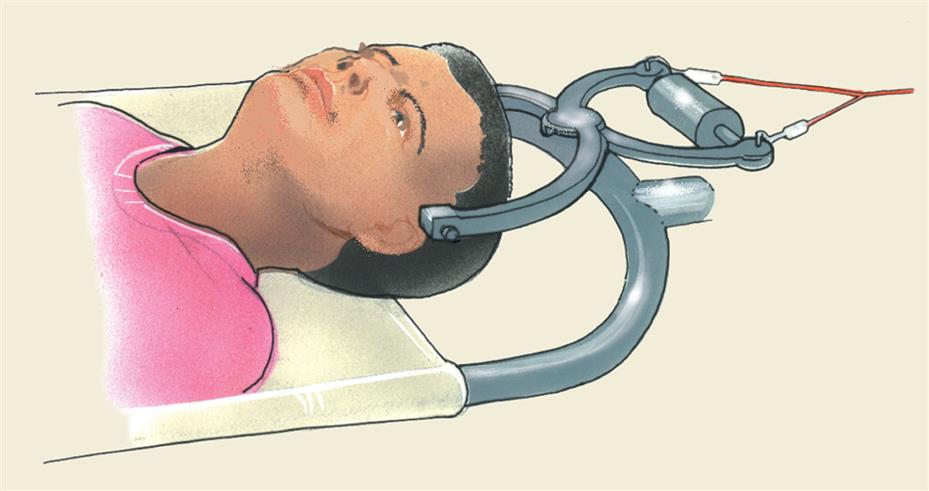

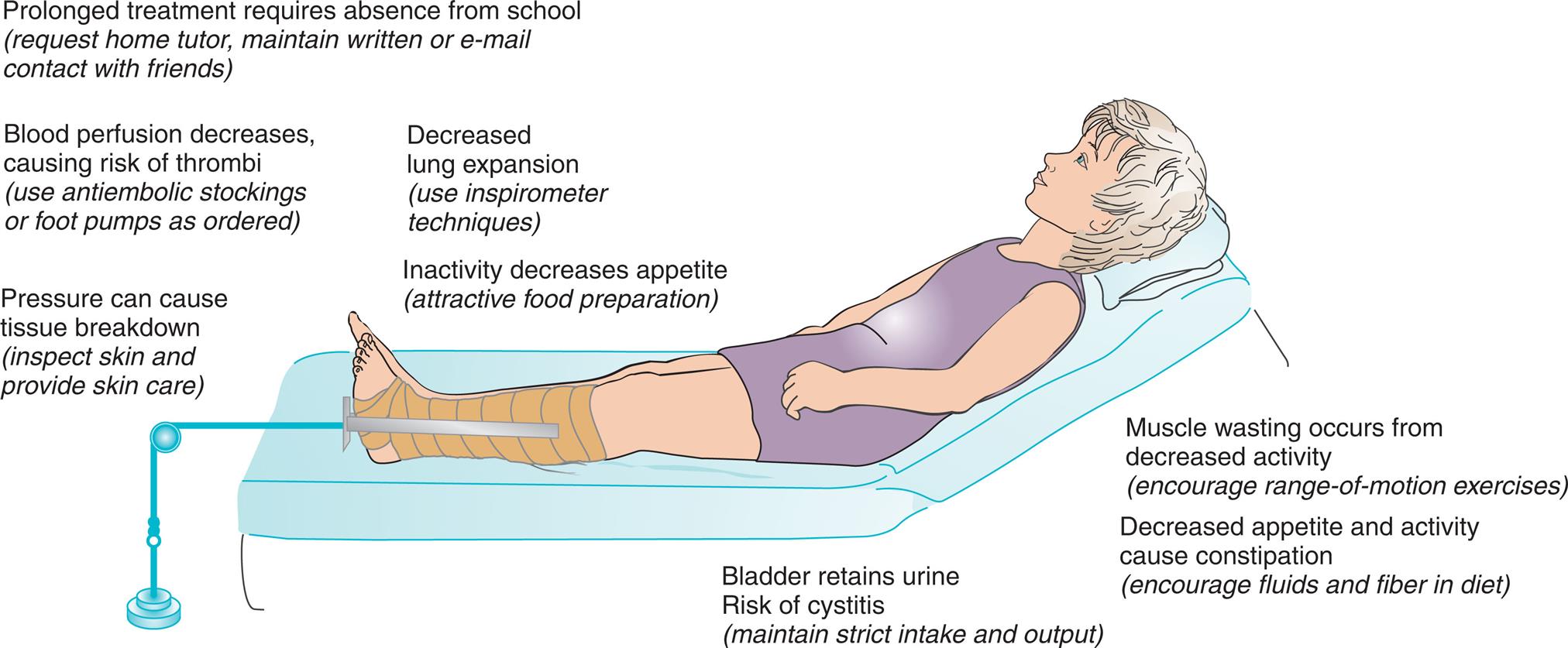

In skeletal traction, a Steinmann pin or Kirschner wire is inserted into the bone, and traction is applied to the pin. Daily cleansing of the pin site is essential. “Ninety-ninety” (or ninety degree–ninety degree) traction with a boot cast or sling on the lower leg may be used (Fig. 24.6). Crutchfield, or Barton, tongs may be used in the skull to provide cervical traction (Fig. 24.7). Skeletal traction carries the added risk of infection from skin bacteria that may cause osteomyelitis. The child in traction experiences certain effects as a result of immobilization (Fig. 24.8). Visitors are important to the child in traction, and a school tutor should be contacted so that the child will be able to return to class after healing occurs.

Illustration shows a child lying on bed with trucks and head raised. Effects of traction are as follows: • Prolonged treatment requires absence from school. • Blood perfusion decreases, causing risk of thrombi. • Pressure can cause tissue breakdown. • Decreased lung expansion. • Inactivity decreases appetite. • Bladder retains urine. • Risk of cystitis. • Muscle wasting occurs from decreased activity. • Decreased appetite and activity cause constipation.

Nursing Responsibilities for Traction

The nurse observes the traction ropes to be sure they are intact and in the wheel grooves of the pulleys and that the child’s body is in good alignment. In Bryant’s traction, the legs should be at right angles to the body, with the buttocks raised sufficiently to clear the bed. In all types of traction, elastic bandages should be neither too loose nor too tight. A jacket restraint may be used to prevent the child from turning from side to side. The weights are not removed after they are applied. Continuous traction is necessary. The weights must hang free, and room furnishings, such as a chair, must not obstruct the pull of the weights. The weights are not lifted or supported when the bed is moved.

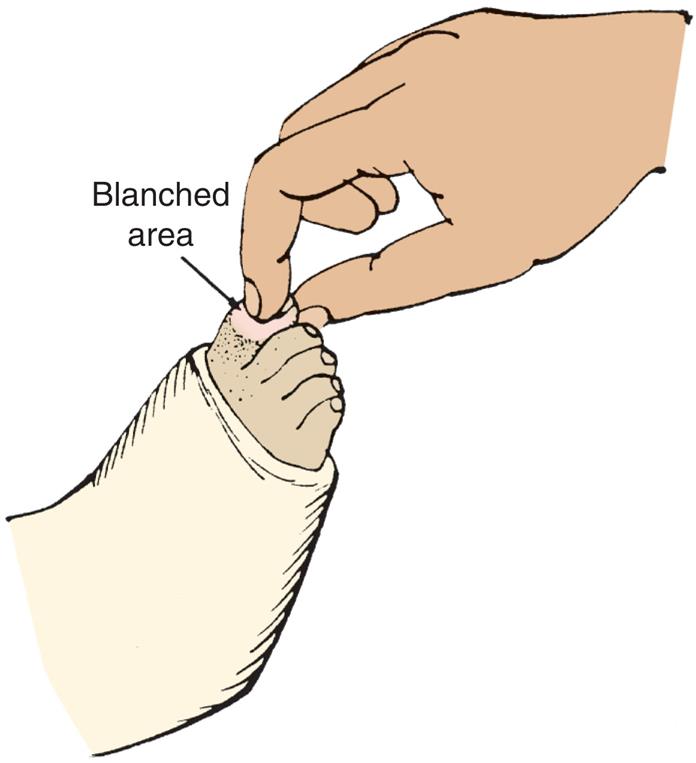

The nurse performs frequent neurovascular checks to the toes to see that they are warm and that their color is good (Fig. 24.9). Observations of conditions such as cyanosis, numbness, or irritation from attachments; tight bandages; severe pain; hypoxia; or the absence of pulse rates in the extremities are reported immediately to the nurse in charge. A specific and serious complication of any traction is Volkmann’s ischemia (iskhein, “to hold back,” and haima, “blood”), which occurs when the circulation is obstructed. When the legs are elevated overhead, as in Bryant’s traction, there is gravitational vascular drainage. Arterial occlusion can cause anoxia of the muscles and reflex vasospasm, which when unnoticed could result in contractures and paralysis.

The child is bathed, and back and buttock care are given. Sheepskin padding may also be used. The sheets are pulled taut and are kept free of crumbs. The jacket restraint is changed when it is soiled. The child is encouraged to drink plenty of fluids and to eat foods that are high in roughage to prevent constipation caused by a lack of exercise. Because the child in traction is unable to sit upright when eating, special precautions to prevent choking and aspiration during mealtime are a priority nursing responsibility. Stool softeners may be necessary. A fracture pan is used for bowel movements, and a careful record is kept of eliminations. Deep-breathing exercises are encouraged to prevent the collection of fluid in the lungs caused by the child’s immobility. These exercises may be done by blowing bubbles or by blowing a pinwheel.

Diversional therapy is important because hospitalization may be lengthy. Toys may be securely suspended over the child’s head so they are within easy reach. The child’s crib is taken to the playroom when possible so the child can experience the excitement of the activities there.

DVDs, iPads, computer games, stories, and other forms of entertainment are important aspects of a total nursing care plan. Pain control is essential. Parents are encouraged to visit the child as often as possible. With proper treatment, the prognosis for the child with this condition is good. When prolonged hospitalization is necessary, the child’s school should be contacted to provide appropriate study materials in order to help the child maintain current grade status.

Neurovascular Checks

A priority nursing responsibility in the care of a child with a fracture who is in traction or who has a cast or Ace bandage in place is to perform neurovascular assessments or neurovascular checks at regular intervals (Skill 24.1). Any abnormalities should be reported promptly so that early intervention can prevent complications from developing (Fig. 24.10).

Illustrations of different bones with fractures are as follows: • Humeral fracture: Breaking the humerus can damage the radial nerve. Check for sen sation over the dorsum of the index finger. To check motor function, ask the patient to hyperextend the thumb. • Radial fracture: A break in the radius can damage the medial as well as the radial nerve. Besides checking sensory and motor function of the radial nerve, evaluate medial nerve function: Check for sensation on the palmar surface of the fingers and the thumb half of the palm. To check motor function, ask the patient to touch the thumb to the tip of the little finger. • Ulnar fracture: Breaking the ulna can damage the ulnar nerve. Check sensation on the ulnar border of the hand from the little finger to the ring finger. To check motor function, ask the patient to abduct, or spread, his or her fingers. • Femoral fracture: A break in the femur can damage the peroneal nerve. Check for sensation over the top of the foot between the first and second toes. To check motor function, ask the patient to dorsiflex the foot, pointing his or her toes toward the head. • Fibular fracture: Breaking the fibula also can damage the peroneal nerve. Lack of sensation between the first and second toes on top of the foot or an inability to dorsiflex the foot is a sign of peroneal nerve damage. • Tibial fracture: A break in the tibia can damage the tibial nerve. To check for sensory damage, ask the patient if the medial side of the sole of his foot feels warm. To evaluate motor function, ask this patient to plantarflex the foot, pointing the toes down.

Nursing Care Plan 24.1 describes interventions for the child in traction.

Assessing for Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome is a progressive loss of tissue perfusion

caused by an increase in pressure resulting from edema or swelling that presses on the vessels and tissues. Circulation is compromised, and the neurovascular check is abnormal.

Compartment syndrome can be caused by a cast that is too tight and compromises circulation or by excessive edema that causes ischemia. Often, surgical intervention (fasciotomy) is required to relieve pressure and to restore circulation. An important nursing responsibility is to provide frequent neurovascular checks on the distal fingers or toes of any injured limb to enable early intervention.

Treatment of Fractures with Casts

Nursing Care of a Child in a Cast

A cast is a device used to immobilize a fracture site, usually including the joints above and below the fracture. Casts are constructed of plaster of Paris or a synthetic material such as fiberglass. Fiberglass casts are lighter than plaster casts and come in various bright colors but cannot be

written on as easily as plaster casts can. If the proper lining is used under the fiberglass cast, the cast is water resistant and can be washed and dried, whereas the plaster cast will deteriorate if it becomes wet. When applied, the fiberglass cast dries within half an hour compared with the plaster cast, which takes 10 to 72 hours to dry and must be handled carefully with open palms and extended fingers to prevent indents that can create pressure areas on the skin during this drying time.

Nursing responsibilities include elevating the affected extremity on a pillow and performing frequent neurovascular checks on the distal digits (see Skill 24.1). Before discharge, the nurse teaches the child and parents how to care for the cast and how to support the cast to prevent the extremity from assuming a dependent position that could compromise circulation. The child is taught safe transfer from bed to wheelchair and safe crutch-walking techniques (e.g., being sure to keep the body weight on the hands and not the axillae). Parents are also taught how to check whether the cast is too loose or too tight and when to return to the clinic or health care provider.

The child should be prepared for the experience of cast removal because the cast cutter can appear and sound threatening. After cast removal, the skin can be expected to be dry and caked. Lotion and soothing baths are advised. Care of a child in a spica cast is discussed in Chapter 14. Nursing care of traumatic injuries to the musculoskeletal system also includes providing emotional support regarding body image and maintenance of skin integrity, encouraging independence, and providing developmentally appropriate activities related to school progress and prevention of future injuries.

Disorders and Dysfunction of the Musculoskeletal System

Osteomyelitis

Pathophysiology

Osteomyelitis is an infection of the bone that generally occurs in children younger than 1 year of age and in those between 5 and 14 years of age. Long bones contain few phagocytic cells (white blood cells [WBCs]) to fight bacteria that may come to the bone from another part of the body. The inflammation produces an exudate that collects under the marrow and cortex of the bone.

Staphylococcus aureus is the organism most often responsible for osteomyelitis in children older than 5 years of age, and children with community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) accounts for almost 50% of the cases (Robinette and Shah, 2020). Haemophilus influenzae is the most common cause in younger children. This incidence may be reduced by the widening practice of routine infant immunization against this organism. Other causative organisms include group A streptococci and pneumococci. Salmonella and Pseudomonas are organisms often found in adolescents who are intravenous (IV) drug users. Osteomyelitis may be preceded by a local injury to the bone, such as an open fracture, burn, or contamination during surgery. It may also follow a furuncle, impetigo, and abscessed teeth. In neonates, a heel puncture or scalp vein monitor can be the predisposing site of infection. Infective emboli may travel to the small arteries of the bone, setting up local destruction and abscess. For this reason, a careful search for infection in other bones and soft tissues is necessary.

The vessels in the affected area are compressed, and thrombosis occurs, producing ischemia and pain. The collection of pus under the periosteum of the bone can elevate the periosteum, which can result in necrosis of that part of the bone. If the pus reaches the epiphysis of the bone in infants, infection can travel to the joint space, causing septic arthritis of that joint.

Local inflammation and increased pressure from the distended periosteum can cause pain. Older children can localize the pain and may limp. Younger children and infants will show decreased voluntary movement of that extremity. Associated muscle spasms can cause limited active ROM. The child may refuse to stand or walk. Signs of local inflammation may be present. A detailed history may show possible sources of primary infection. Blood cultures to identify the organism may be valuable if the child has not been given antibiotics for the primary infection. A urine test for the presence of bacterial antigens and a tissue biopsy may be helpful to establish the diagnosis.

Diagnosis

There is an elevation in WBC count and ESR. X-ray examination may initially fail to reveal the infection but a MRI may provide precise detail. A microbiology culture of aspirated drainage or a bone scan may be diagnostic.

Treatment and Nursing Care

Prompt and vigorous treatment is essential to ensure a favorable prognosis. Intravenous antimicrobial therapy are prescribed for a 4- to 6-week period. The high doses required indicate a nursing responsibility to monitor the infant or child for toxic responses and to ensure long-term compliance. The joint may be drained of pus arthroscopically or surgically to reduce pressure and to prevent bone necrosis. A complication should be suspected if fever lasts beyond 5 days. The use of appropriate pain-relieving medications and gentle handling to minimize pain are essential. The child should be positioned comfortably with the limb supported by pillows or blanket rolls.

Bed rest is followed by wheelchair access, but weight bearing should be avoided. Diversional therapy, physical therapy, and tutorial assistance for school-age children should be provided so that they can return to their classes and classmates after discharge. Close interaction with home care providers is indicated. Passive ROM and physical therapy is important. A normal ESR test is predictive of healing.

Duchenne’s Muscular Dystrophy

Pathophysiology

The muscular dystrophies are a group of genetic disorders in which progressive muscle degeneration occurs with resulting death of muscle fibers (Bharucha-Goebel, 2020). The childhood form (Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy) is the most common type affecting all races and ethnic groups. It has an incidence of about 1 in 3600 live-born male infants of all races and ethnic groups (Bharucha-Goebel, 2020). It is a sex-linked recessive inherited disorder that occurs only in boys. Dystrophin, a protein in skeletal muscle, is absent. Becker’s pseudohypertrophic muscular dystrophy occurs later in childhood, progresses more slowly, and is not as common as Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy.

Manifestations

Symptoms are noted generally between 2 and 6 years of age; however, a history of delayed motor development during infancy may be evidenced. The calf muscles in particular become hypertrophied. The term pseudohypertrophic (pseudo, “false,” and hypertrophy, “enlargement”) refers to this characteristic. Other signs include progressive weakness as evidenced by frequent falling, clumsiness, contractures of the ankles and hips, and Gowers’ maneuver (a characteristic way of rising from the floor).

Laboratory findings show marked increases in serum creatine phosphokinase. Muscle biopsy shows a degeneration of muscle fibers and their replacement by fat and connective tissue and is considered diagnostic. A myelogram (a graphic record of muscle contraction as a result of electrical stimulation) shows decreases in the amplitude and duration of motor unit potentials. A serum blood polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the gene mutation is diagnostic for this condition. The disease becomes progressively worse, and wheelchair confinement may be necessary. Death usually results from cardiac failure or respiratory tract infection. Intellectual impairment is not uncommon.

Treatment and Nursing Care

The use of prednisone has shown some promise in slowing the decline of muscle strength. Studies are in place concerning the use of glutamine and creatine for muscle weakness, the enzyme transferase to block muscle wasting, and urotrophin to replace the missing dystrophin. Treatment at this time is mainly supportive to prevent contractures and to maintain the quality of life. Cardiac and respiratory complications are common. A multidisciplinary team should provide psychological support, nutritional support, physiotherapy, social and financial assistance, and, when necessary, respite and hospice care. There is ongoing research involving genetic therapy.

Compared with other children with disabilities, some children with muscular dystrophy may appear passive and withdrawn. Early on, depression may be seen because the child cannot compete with peers. Social and emotional pressures on the child and family are great.

Slipped Femoral Capital Epiphysis

Pathophysiology

A slipped femoral capital epiphysis (SFCE), also known as coxa vara, is the spontaneous displacement of the epiphysis of the femur. It most often occurs during rapid growth of the preadolescent and is not related to trauma. The elevated level of circulating hormones of puberty, combined with the mechanical load of excess weight on the epiphysis, results in the displacement of the head of the femur in relation to the femoral neck. More than 65% of children with SFCE are obese (Sankar et al., 2020). Increased rates of obesity have correlated with increased rates of the occurrence of SFCE. The epiphysis of the femur widens, and then the femoral head and epiphysis remain in the acetabulum. The head of the femur then rotates and displaces. Symptoms include thigh pain and a limp or the inability to bear weight on the involved leg. An x-ray study confirms diagnosis.

Treatment

The child is placed in traction to minimize further slippage, and then surgery is scheduled to insert a screw to stabilize the bone. Surgery is followed by a gradual return to activity. Further surgery may be scheduled after healing occurs to correct any deformity that is present. Serious complications may include disturbance of circulation to the epiphysis, resulting in necrosis of the head of the femur.

Nursing Care

The general principles of caring for a child in traction and preoperative and postoperative care are used (see Chapters 14 and 22). The nurse assists in performing orders regarding ROM activities, guides gradual resumption of weight bearing with the help of crutches, and encourages referrals to maintain school studies. Education concerning management of weight is important postoperatively.

Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease (Coxa Plana)

Pathophysiology

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease is one of a group of disorders called the osteochondroses (osteo, “bone,” chondros, “cartilage,” and osis, “disease”) in which the blood supply to the epiphysis, or end of the bone, is disrupted. The tissue death that results from the inadequate blood supply is termed avascular necrosis (a, “without,” vasculum, “vessels,” and nekros, “death”). Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease affects the development of the head of the femur. The incidence is approximately 1 in 1200 (Sankar et al., 2020). The disease is seen most commonly in boys between 5 and 12 years of age. It is unilateral in about 85% of cases. Healing occurs spontaneously during 2 to 4 years; however, marked distortion of the head of the femur may lead to an imperfect joint or degenerative arthritis of the hip in later life. Symptoms include thigh and knee pain, a painless limp, and limitation of motion. X-ray films and bone scans confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease is a self-limiting disorder that heals spontaneously, but slowly, throughout the course of 2 to 4 years. The treatment involves keeping the femoral head deep in the hip socket while it heals and preventing weight bearing. This is accomplished through the use of ambulation-abduction “Petrie” casts or braces that prevent subluxation (sub, “beneath,” and luxatio, “dislocation”) and enable the acetabulum to mold the healing head in such a way that it does not become deformed.

Nursing Care

Nursing considerations depend on the age of the patient and the type of treatment. The general principles of traction, cast, and brace care are used when immobilization of the child is necessary. Teaching and counseling are directed toward a holistic understanding of and interest in the individual child and family. Total immobility or partial mobility is particularly trying for children. The natural inclination to compete physically is thwarted. In some cases surgical immobilization is required. Preoperative and postoperative care and care of a patient in a cast are discussed in Chapters 14 and 22.

Osteosarcoma

Pathophysiology

Osteosarcoma (osteo, “bone,” sarx, “flesh,” and oma, “tumor”) is a primary malignant tumor of the long bones. The two most common types of bone tumors in children are osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma. The mean age of onset of osteosarcoma is between 10 and 15 years of age, and it occurs most commonly in tall adolescents in the midst of rapid bone growth. The cause is genetic, with children having a history of retinoblastoma at highest risk. Metastasis occurs quickly because of the high vascularity of bone tissue. The lungs are the primary site of metastasis; the brain and other bone tissue are also sites of metastasis.

Manifestations

The patient experiences pain and swelling at the site. In adolescents, this is often attributed to a sports injury or “growing pains.” Flexing the extremity may lessen the pain. Later a pathological fracture may occur. Diagnosis is confirmed by x-ray. A complete physical examination, including CT and a bone scan, is performed.

Treatment and Nursing Care

Treatment of the patient with osteosarcoma consists of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. Radical resection or amputation may be necessary. Internal prostheses are available for most sites. Long-term survival is possible with early diagnosis and treatment.

The nursing care is similar to that for other types of cancer. Problems of body image are particularly important to the self-conscious adolescent. If amputation is necessary, the family and patient will need much support. The nurse anticipates anger, fear, and grief. Immediately after surgery, the stump dressing is observed frequently for signs of bleeding. Vital signs are monitored. The child is positioned as ordered by the surgeon.

Phantom limb pain is likely to be experienced. This is the continued sensation of pain in the limb even though the limb is no longer there. It occurs because nerve tracts continue to report pain. This pain is very real, and an analgesic may be necessary. Rehabilitation measures follow surgical recovery.

Ewing’s Sarcoma

Pathophysiology

In 1921, Dr. James Ewing first described Ewing’s sarcoma, which is a malignant growth that occurs in the marrow of the long bones. It occurs mainly in older school-age children and early adolescents. When metastasis is present on diagnosis, the prognosis is poor. Without metastasis, there is a 60% survival rate. The primary sites for metastasis are the lungs and long bones.

Treatment and Nursing Care

Amputation is not generally recommended for Ewing’s sarcoma because the tumor is sensitive to radiation therapy and chemotherapy. This is a relief to the child and family. The child is warned against weight bearing on the involved bone during therapy to help prevent pathological fractures. Patients must be prepared for the effects of radiation therapy and chemotherapy. The nurse supports the family members in their efforts to gain equilibrium after such a crisis. Long-term follow-up care is important in detecting the late effects of the treatment.

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis)

Pathophysiology

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common arthritic condition of childhood. It is a systemic autoimmune disease that involves the joints, connective tissues, and viscera, and it differs somewhat from adult rheumatoid arthritis. It is not a rare disease. Multiple genes are involved with an external trigger that initiates signs and symptoms such as a sports injury or bacterial or viral infection treated with antibiotics (Wu and Rabinovitch, 2020).

Manifestations and Types

JIA has several distinct classifications.

- 1. Oligo arthritis involves four or fewer joints, and uveitis (inflammation of the eye) is common in about 30% of these children.

- 2. Polyarthritis involves five or more joints, and uveitis occurs in about 10% of these children.

- 3. Systemic arthritis is characterized by fever, rash, and joint inflammation. Uveitis occurs in about 10% of these children. The systemic form is manifested by an intermittent spiking fever above 39.5°C (103 °F) persisting for more than 10 days, a nonpruritic macular rash, abdominal pain, an elevated ESR, C-reactive protein in laboratory tests, the presence of antinuclear antibodies, and possibly an enlarged liver and spleen. It occurs most often in children ages 1 to 3 years and 8 to 10 years. Joint symptoms may be absent at onset, but usually arthritis develops in most patients.

Treatment

The goals of therapy are to accomplish the following:

Medications such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and methotrexate may also be provided. The child should undergo frequent laboratory tests to monitor closely for side effects. Steroids may be administered for incapacitating arthritis, uveitis, or life-threatening complications. Immunosuppressants, such as Etanercept, adalimumab, canakinumab, and tocilizumab, may be prescribed, and nursing responsibilities include utilizing interventions to prevent infection and close observation for serious side effects. Monitoring for uveitis by an ophthalmologist is advised. Dietary management and physical therapy are important.

Nursing Care

The nurse functions as a member of a multidisciplinary health care team that includes the pediatrician, rheumatologist, social worker, physical therapist, occupational therapist, psychologist, ophthalmologist, and school and community nurses. Physical and occupational therapy preserve joint function and mobility. Occupational therapy helps with activities of daily living. Resting in a bed with a supportive, flat mattress is helpful. Resting splints during sleep can prevent flexion contractures from developing. Moist heat and exercise are advised, and whirlpool baths and hot packs relieve pain and stiffness. Therapeutic play facilitates compliance with exercise regimens. Swimming can help maintain joint mobility. Sleep, rest, and general health measures are important. The school nurse can be contacted to promote normal growth and development in school-related activities. Homeschooling, if needed, is available in most school districts. Unnecessary restrictions should be avoided because they can lead to rebellion and noncompliance. JIA inhibits the child’s social interactions and can interfere with development of a positive self-concept. The Arthritis Foundation provides services to parents and nurses involved in patient care.

This long-term disease is characterized by periods of remission and exacerbations. Nurses can serve as advocates for the child—that is, they can help alleviate stress by recognizing the impact of the disease and by openly communicating with the child, the family, and other members of the health care team. Nurses support the child and family members as the condition often extends into adulthood.

Torticollis (Wry Neck)

Pathophysiology

Torticollis (tortus, “twisted,” and collum, “neck”) is a condition in which neck motion is limited and the cervical spine is rotated because of shortening of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It can be either congenital or acquired and can also be either acute or chronic. The most common type is a congenital anomaly in which the sternocleidomastoid muscle is injured during birth. It is associated with breech and forceps delivery and may be seen in conjunction with other birth defects, such as congenital hip dysplasia.

Manifestations

In congenital torticollis, the symptoms are present at birth. The infant holds the head to the side of the muscle involved. The chin is tilted in the opposite direction. There is a hard, palpable mass of dense fibrotic tissue (fibroma) within the muscle. Passive stretching and ROM exercises and physical therapy may be indicated. Feeding and playing with the infant can encourage turning to the desired side for correction. Surgical correction is indicated if the condition persists beyond 2 years of age (Mistrovich and Spiegel, 2020b).

Acquired torticollis is seen in older children. It may be associated with injury, inflammation, neurological disorders, and other causes. Nursing intervention is primarily that of detection. Infants who have limited head movement require further investigation.

Scoliosis

Pathophysiology

The most prevalent of the three skeletal abnormalities shown in Fig. 24.11 is scoliosis. Scoliosis refers to an S-shaped curvature of the spine. During adolescence, scoliosis is more common in girls. Many curvatures are not progressive and may necessitate only periodic evaluation. Untreated progressive scoliosis may lead to back pain, fatigue, disability, and heart and lung complications. Skeletal deterioration does not stop with maturity and may be aggravated by pregnancy.

Three illustrations show the abnormal curvatures of the spine. A) A lateral view of the spine with an arrow pointing to deeper than normal anterior curve of the lumbar vertebrae. B) A lateral view of the spine with an arrow pointing to deeper than normal posterior curve of the thoracic vertebrae. C) A posterior view of the spine with an arrow pointing to an excessive lateral curve to the right.

Causes

There are two types of scoliosis: functional and structural. Functional scoliosis is usually caused by poor posture, not by spinal disease. The curve is flexible and easily correctable. Structural or fixed scoliosis is caused by changes in the shape of the vertebrae or thorax. It is usually accompanied by rotation of the spine. The hips and shoulders may appear uneven. The patient cannot correct the condition by standing in a straighter posture.

Idiopathic scoliosis is a curve of at least 10 degrees noted on an anterior-posterior spinal x-ray. The specific cause is unknown, but genetic, hormonal, anatomical, and functional factors are thought to play a role. Infantile idiopathic scoliosis often resolves spontaneously. About 80% of curvatures under 20 degrees will resolve but curvatures over 20 degrees will often progress, and 80% of idiopathic scoliosis affects children 11 years of age and older.

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms develop slowly and are not painful, so detection is usually via a screening test performed by the school nurse that reveals shoulders that are different heights, a one-sided rib bump, and a prominent scapula. This asymmetry is seen from the back when the child leans forward. Definitive diagnosis is made by a spinal x-ray study while the child is in an upright position.

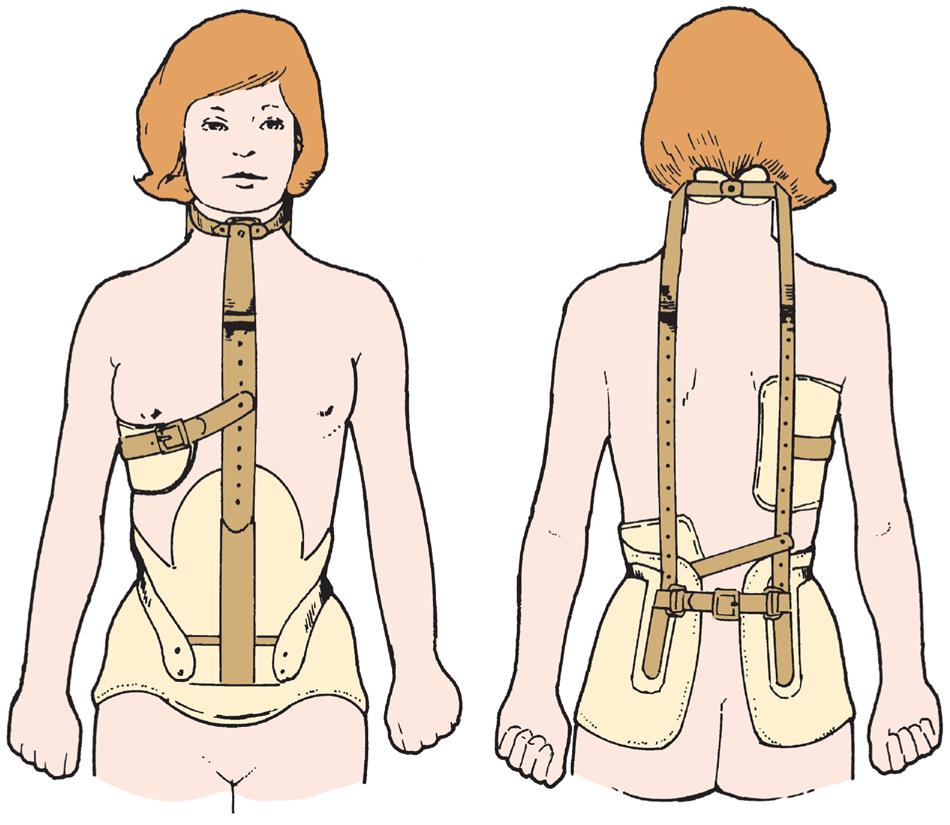

Treatment

Treatment is aimed at correcting the curvature and preventing more severe scoliosis. Curves up to 20 degrees do not necessitate treatment but are carefully followed with exercise to increase muscle tone and posture. Curves between 20 and 40 degrees require the use of a Milwaukee brace (Fig. 24.12). This apparatus exerts pressure on the chin, pelvis, and convex (arched) side of the spine. It is worn approximately 16 to 23 hours a day and is worn over a T-shirt to protect the skin. An underarm modification of the brace (the Boston brace) is proving effective for patients with low curvatures. It is less cumbersome and more acceptable to the self-conscious young person. Transcutaneous electrical muscle stimulation (TENS) and exercise have also proven effective in the treatment of scoliosis.

Severe scoliosis beyond a curvature of 45 degrees necessitates surgery to fuse the bones and stop the progression of the deformity. A Harrington rod, Dwyer instrument, or Luque wires may be inserted for immobilization during the time required for the fusion to become solid. Halo traction may be used when there is associated weakness or paralysis of the neck and trunk muscles (Fig. 24.13); this traction is also used in treating cervical fractures and fusions. An anterior/posterior plastic shell or orthotic may be worn for several months until the spine is stable. Helping the teen cope with a body brace and maintain a positive self-image is an important and challenging aspect of care. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a vertebral expandable prosthetic titanium rib (VEPTR) surgery that expands the thoracic space and is indicated in patients with severe spinal curves that restricts lung function. This treatment allows for the development of maximum height of the patient before spinal fusion is necessary. The use of “Shilla growth guidance rods” is another approach to treatment; with this method, expandable rods are placed subcutaneously and lengthened as the child grows until skeletal maturity occurs, but this technique remains under study. Intervertebral stapling or tethers are also under investigation as optional treatment (Mistovich and Spiegel, 2020a).

A child with a halo vest with a steel or iron halo attached to the head by 6 to 8 screws inserted into the outer skull and rigid bars on both sides are connecting halo to the vest worn around the chest.

Nursing Care

Community Nursing

The management of scoliosis begins with screening. This is undertaken before middle school. It should be a part of every yearly physical examination for prepubescent youngsters. Camp nurses also need to be aware of symptoms. Early recognition is of utmost importance in detecting mild cases amenable to nonsurgical treatment.

The adolescent is prepared by explaining the purpose of the procedure and by being reassured that it merely entails observing the back while standing and bending forward. In scoliosis, one shoulder is noted to be higher than the other, a scapula may be prominent, the arm-to-body spaces may be unequal, or a hip may protrude; one arm may appear longer than the other when the person bends forward. Referrals are made as indicated for those who may require further assessment and treatment. Routine preoperative nursing care of the adolescent is necessary for spinal fusion. Much postoperative nursing care is directly related to combating the physical results of immobilization (see Fig. 24.8). The body systems become sluggish because of inactivity. This is evidenced in the gastrointestinal tract by anorexia, irregularity, and constipation. Allowing the adolescent to select foods with the aid of the dietitian helps to improve appetite. Increasing fluid intake reduces constipation. The adolescent and parents are introduced to the multidisciplinary health care team. Postoperative exercise, physical therapy, and promotion of adolescent school and developmental tasks are essential aspects of nursing care.

Sports Injuries

A high percentage of adolescent males and females participate in athletic activities. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that a complete physical examination be given at least every other year during adolescence and that sports-specific examinations be provided for those involved in strenuous activity on entry into middle school or junior high school. These examinations should be updated by an annual questionnaire. The family history and an orthopedic screening are important for identifying risk factors.

Prevention

Several factors help prevent sports injuries. Some of these are adequate warm-up and cool-down periods; year-round conditioning; careful selection of activity according to the physical maturity, size, and skill necessary; proper supervision by adults; safe, well-fitting protective equipment; and avoidance of participation when in pain or injured. Proper diet and fluids are also necessary. A few of the more common injuries are listed in Table 24.1. The nurse has a major role in educating and directing parents to sources of accurate information to ensure that the physical, emotional, and maturational levels of the adolescent are appropriate for the activity. (See the Health Promotion box) (Rabatin et al., 2020). Parents are encouraged to inquire about the capabilities of coaches or supervising personnel and the availability of emergency services before the beginning of the competition. Concussions are discussed in Chapter 23.

Table 24.1

Family Violence

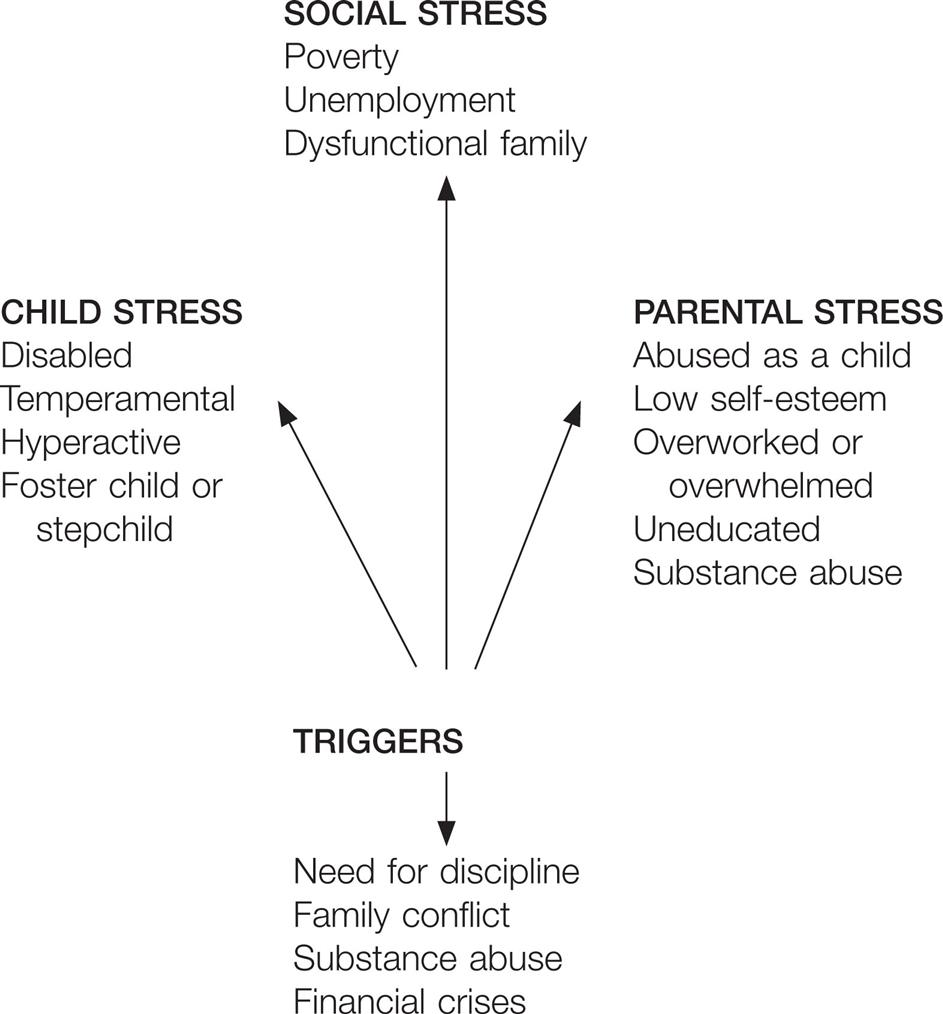

Violence has become a problem that affects children of all social classes across the nation. Family violence includes spousal abuse and child abuse, neglect, and maltreatment. Community violence is seen in neighborhoods where even non–gang-related adolescents arm themselves with guns and knives for protection. Preschoolers who are repeatedly allowed to watch violent programs on television or play aggressive computer games may be learning antisocial coping skills they will use as they grow and mature. Parents should control the time spent watching television and the content of the programs so that television exposure results in the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and information that will motivate learning. In homes where spousal or child abuse occurs, children learn the behaviors they will likely practice when they become adults, and the abuse cycle continues. Parents who are abusive are not usually psychotic or criminal. They may have a knowledge deficit about child care needs and child growth and development. Abusive parents are often without a support system; are perhaps alone, angry, or in crisis; or have unrealistic expectations.

Child Abuse

Kempe (1962) coined the term battered child syndrome in his landmark article in the Journal of the American Medical Association. It refers to “a clinical condition in young children who have received serious physical abuse, generally from a parent or foster parent.” The impact of Kempe’s research was considerable and focused the attention of health care providers on unexplained fractures and signs of physical abuse. Today, most authorities consider Kempe’s definition narrow and have broadened it to include neglect and maltreatment.

According to the National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect (Dubowitz and Lane, 2020), the incidence of the following aspects of child abuse has been increasing:

- • Emotional abuse: intentional verbal acts that result in a destruction of self-esteem in the child; can include rejection or threatening the child.

- • Emotional neglect: an intentional omission of verbal or behavioral actions that are necessary for development of a healthy self-esteem; can include social or emotional isolation of a child.

- • Sexual abuse: involves an act that is performed on a child for the sexual gratification of the adult.

- • Physical neglect: the failure to provide for the basic physical needs of the child, including food, clothing, shelter, and basic cleanliness.

- • Physical abuse: the deliberate infliction of injury on a child; suspected when an injury is not consistent with the history or developmental level of the child.

The temperament of the child and the parent can be a causal factor in child abuse. Children who are different from others in any way are at particular risk. This includes preterm infants, sick or disabled children, and merely unattractive children. Unwanted or illegitimate infants and stepchildren are especially vulnerable. It has been noted that people are often reluctant to report occurrences in middle- and upper-income families or when the incident involves friends or relatives.

Federal Laws and Agencies

By 1963 the U.S. Children’s Bureau drafted a model mandatory state reporting law that has been adopted in some form in all states (see the Legal and Ethical Considerations box). This law aids in establishing statistics and is based on the need to provide therapeutic help to both the child and family. Immunity from liability is provided for persons reporting suspected cases. Most states have penalties for failure to report suspected child abuse. Referrals usually are made to the local child protective services, and a caseworker is assigned.

Nursing Care and Interventions

Nursing intervention for high-risk children is of utmost importance (Box 24.1). One approach currently taken is to identify high-risk infants and parents during the prenatal and perinatal periods. Predictive questionnaires are being used as screening tools in some clinics. Many hospitals also provide closer follow-up of mothers and newborns. Maternal–infant bonding and its significance to later parent–child relationships has been explored.

Nurses in obstetrical clinics have the opportunity to observe parents and their abilities to cope. The history of the parent(s), desirability of the pregnancy, number of children already in the family, financial and personal stability of the family, types of support systems, and other factors may have a bearing on how the parents accept the new offspring. Pertinent observations include a description of parent–newborn interaction. Both verbal and nonverbal communications are important, as is the level of body and eye contact. Lack of interest, indifference, or negative comments about the sex, looks, or temperament of the infant could be significant.

In other areas, a cooperative team approach is necessary. This may include services such as family planning, protective services, day care centers, homemakers, parenting classes, self-help groups, family counseling, child advocates, and a continued effort to reduce the incidence of preterm birth. Other related areas include financial assistance, employment services, transportation, emotional support and encouragement, and long-term follow-up care.

Individual nurses can help detect child abuse by maintaining a vigilant approach in their work settings. Record keeping should be factual and objective. The pediatric nurse should make a point of reviewing old records of their patients, which may show repeated hospitalizations, x-ray films of multiple fractures, persistent feeding problems, a history of failure to thrive, and a history of chronic absenteeism from school. Neglect or delay in seeking medical attention for a child or failure to obtain immunization and well-child care can be significant findings. Children who seem overly upset about being discharged must be brought to the attention of the health care provider. Runaway teenagers are often victims of abuse.

The abused child is approached quietly, and preparation for any treatment is carefully explained in advance. The number of caretakers should be kept to a minimum. The child may be able to express some hostility and fear through play or drawing. It is not unusual for these children to be unresponsive or openly hostile or to show affection indiscriminately. Direct questioning is kept to a minimum. Praise is used when appropriate. Activities that promote physical and sensory development are encouraged. The nurse avoids speaking to the child about the parents in a negative manner. Other professionals are consulted about setting limits for poor behavior.

The nurse must acknowledge that there are always two victims in cases of child abuse: the child and the abuser. Because of personal problems, the abuser often leads an isolated life. Some have themselves been battered or neglected as children. Many have unrealistic expectations about the child’s intelligence and capabilities. There may be a role reversal in which the child becomes the comforter. Although removing the child from the home is one answer, many authorities believe this can be more detrimental in the long run.

Being open to parents during this type of crisis is difficult but essential if the nurse wishes to be part of the solution rather than part of the problem. When placement in a foster home is necessary, parents experience grief, loss, and remorse. The child also mourns the loss of the family, even though there has been abuse. The nurse should be aware of the child’s needs and facilitate the expression of feelings of loss. The nurse who recognizes the potential for violence within all of us is better able to respond to this complex problem.

Cultural and Medical Issues

Multiple factors should be considered when evaluating the child. A culturally sensitive history is essential. The nurse should be aware that what appears to be a cigarette burn could be a single lesion of impetigo. Slate grey nevi can be mistaken for bruises. A severe diaper rash caused by a fungal infection can look like a scald burn. In some cases, loving parents can injure infants when shaking them to wake or feed them. They are not aware of the danger of “shaken baby syndrome.”

Some cultural practices can be interpreted as physical abuse if the nurse is not culturally aware of folk healing and ethnic practices. For example, “coining” of the body by the Vietnamese to allay disease can cause welts on the body (see Chapter 34). Burning small areas of the skin to treat enuresis is practiced by some Asian cultures. Forced kneeling is a common Caribbean discipline technique. Yemenite Jews treat infections by placing garlic preparations on the wrists, which can result in blisters. The Telugu people of southern India touch the penis of a child to show respect.

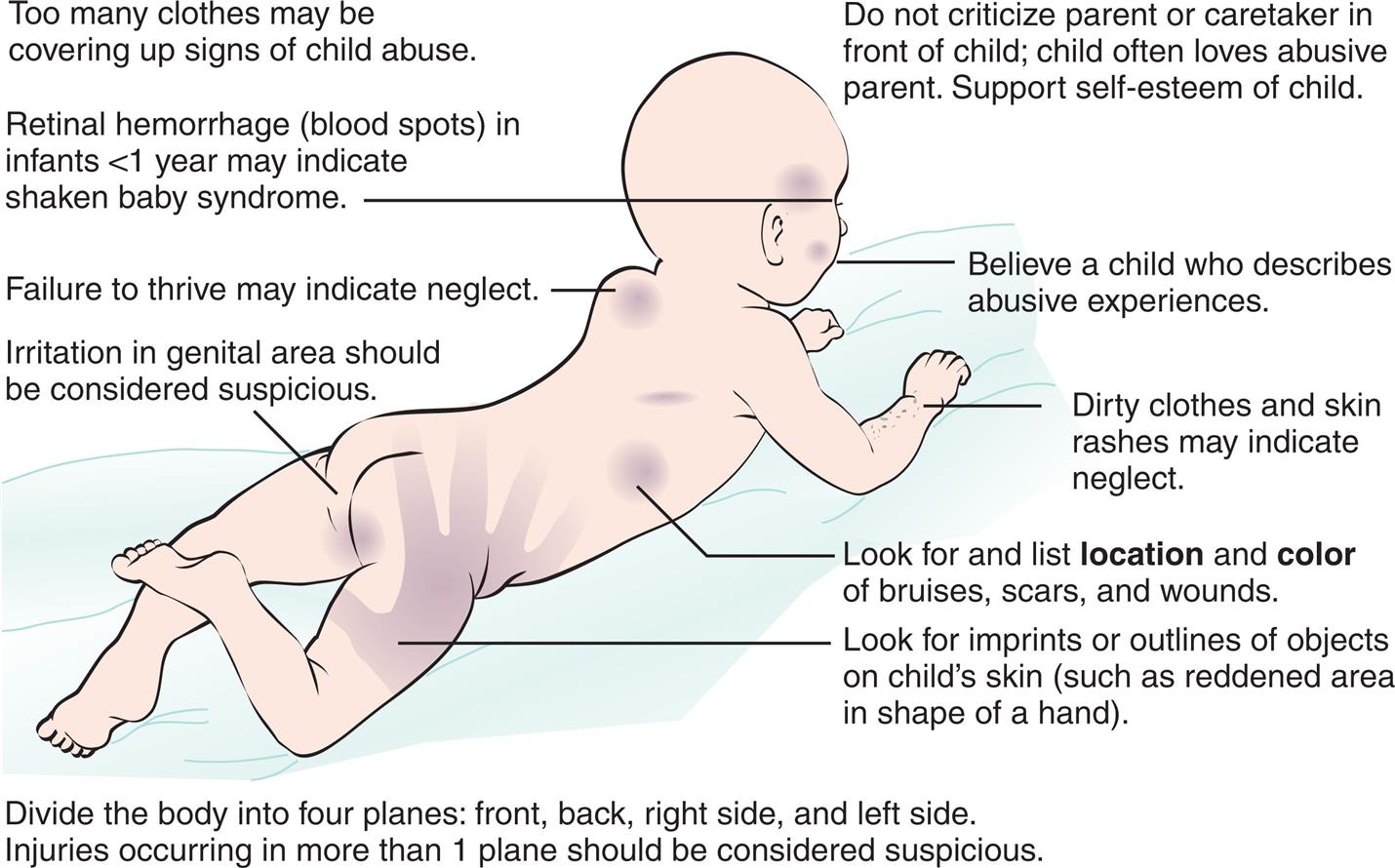

The nurse should document all signs of abuse and interaction as well as verbal comments between the child and parents (Fig. 24.14). Child protective services should oversee any investigation that is warranted. Providing support to parents and child, including an opportunity to talk privately, and planning for follow-up care are basic nursing responsibilities. Parent education concerning growth and development is valuable.

The following should be addressed while assessing for child abuse: • Too many clothes may be covering up signs of child abuse. • Do not criticize parent or caretaker in front of child; child often loves abusive parent. Support self-esteem of child. • Divide the body into four planes: front, back, right side, and left side. Injuries occurring in less than one plane should be considered suspicious. Illustration of an infant with marks on the body is labeled clockwise as: believe a child who describes abusive experience, dirty clothes and skin rashes may indicate neglect, look for and list location and color of bruises, scars, and wounds, look for imprints or outlines of objects on child’s skin (such as reddened area in shape of a hand), irritation in genital area should be considered suspicious, failure to thrive may indicate neglect, and retinal hemorrhage (blood spots) in infants less than one year may indicate shaken baby syndrome.

Get Ready for the Next-Generation NCLEX® Examination!

Key Points

- • The age, neurological development, and motor milestones achieved will influence the nursing assessment of the musculoskeletal system in a growing child.

- • The normal gait of a toddler is wide and unstable. By 6 years of age, the gait resembles an adult walk.

- • Immobility causes a deceleration of body metabolism.

- • Injury to the epiphyseal plate at the ends of long bones is serious during childhood because it may interfere with longitudinal growth.

- • In a compound fracture, a wound in the skin accompanies the broken bone, and there is added danger of infection.

- • Any delay in neurological development can cause a delay in mastery of motor skills, which can result in altered skeletal growth.

- • Children who do not walk by 18 months of age should be referred for follow-up care.

- • Rest, ice, compression, and elevation are the principles of managing soft tissue injuries.

- • Pain over a muscle area that does not respond to medication may indicate a complication known as compartment syndrome.

- • A neurovascular check includes color, warmth, capillary refill time, movement, pulse, sensation, and pain.

- • Frequent neurovascular checks should be performed on the distal digits of a patient with a cast to determine adequate tissue perfusion.

- • Tutorial assistance should be provided to school-age children who are hospitalized or immobilized for long periods of time.

- • Nursing care includes providing emotional support regarding body image and maintenance of skin integrity, encouraging independence, and providing developmentally appropriate activities related to school progress and prevention of future injuries.

- • A complication of any traction is an arterial occlusion termed Volkmann’s ischemia.

- • Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease affects the blood supply to the head of the femur.

- • Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is the most common arthritic condition of childhood.

- • Juvenile idiopathic arthritis can inhibit social interaction and the development of a positive self-image.

- • Treatment of scoliosis includes bracing, exercise, and surgery (spinal fusion).

- • Adolescents who participate in sports are subject to injuries such as concussions and ligament injuries. Activities must be selected carefully according to physical maturity, size, and skill required.

- • A spiral fracture of the femur or humerus may be a sign of child abuse.

- • Child abuse may be physical, emotional, or sexual, or it may involve neglect.

Additional Learning Resources

Go to your Study Guide for additional learning activities to help you master this chapter content.

Go to your Evolve website (http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer) for the following learning resources:

- • Animations

- • Answer Guidelines for Critical Thinking Questions

- • Answers and Rationales for Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

- • Glossary with English and Spanish pronunciations

- • Interactive Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

- • Patient Teaching Plans in English and Spanish

- • Skills Performance Checklists

- • Video clips and more!

Online Resources

- • Arthritis Foundation: https://www.arthritis.org

- • Scoliosis: https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/scoliosis.html

Clinical Judgment and Next-Generation NCLEX® Examination-Style Questions

- 1. A type of fracture in a young child that may be indicative of child abuse is:

- 2. A teenager who had a cast applied after a tibia fracture complains that his pain medication is not working and his pain is still a 9 or 10. The nurse notices some edema of the toes and a capillary refill of 6 seconds. The priority action of the nurse would be to:

- 3. A “neurovascular check” for tissue perfusion includes which of the following observations? (Select all that apply.)

- 4. An abnormal S-shaped curvature of the spine seen in school-age children is:

- 5. A yellow bruise is approximately:

- 6. The nurse reinforces home care instructions for parents of a child who has had an above-the-knee cast applied.

- 7. A 6-year-old sustained a fractured femur and required skeletal traction. Upon entering the room, the nurse overhears the child telling his mother to bring more “bubbles” adding, “Grandpa and I play with them when he visits me.” The nurse notes that the child’s bed is in high Fowler’s position in anticipation that breakfast will arrive in a few minutes. The bedlinen are pulled taunt with a sheet draped loosely over the traction ropes. The child is in proper body alignment with heels rising on the bed. The ropes are noted to be positioned in the wheel grooves of the pulleys with the knots firmly resting against the pulleys themselves. Weights are hanging freely. The nursing notes indicate that the pin sites were last cleansed 12 hours ago and last neurovascular check was documented 3 hours ago.