5:  Ultrasound of the Spleen and Lymphatic System

Ultrasound of the Spleen and Lymphatic System

The spleen – normal appearances and technique

The spleen is the largest organ within the lymphatic system and has many supporting roles within the body, including being integral in supporting the immune system and with blood filtration, recycling red blood cells, and storage of platelets and white blood cells. The spleen normally lies in the left upper quadrant (LUQ), posterior to the splenic flexure and stomach, which often results in poor views when trying an anterior approach because of the gas from the bowel and stomach. Therefore, it is best approached from the left lateral intercostal aspect with the patient supine. Air within the gas-filled bowel will rise anteriorly to the spleen, providing a clearer view. Gentle respiration is frequently more successful than deep inspiration, as the latter brings the lung bases downwards and may obscure a small spleen altogether.

Ultrasound Appearances

The normal spleen has a homogeneous texture, with smooth, clearly defined margins and a pointed inferior edge. It is usually of similar echotexture to the liver (but may be slightly hypo- or hyperechoic in some subjects). Sound attenuation through the spleen is less than that through the liver, requiring the operator to “flatten” the time gain compensation controls to maintain an even level of echoes throughout the organ.

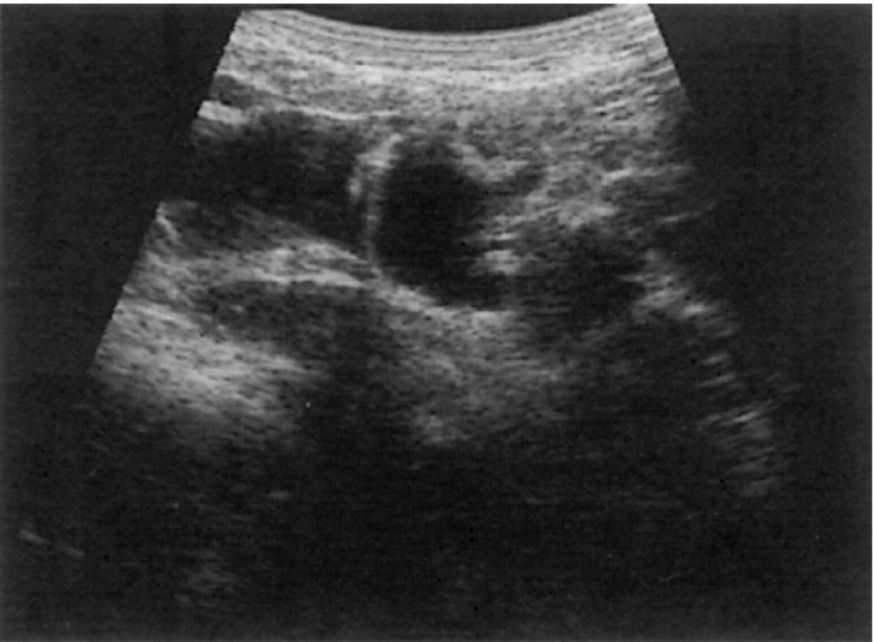

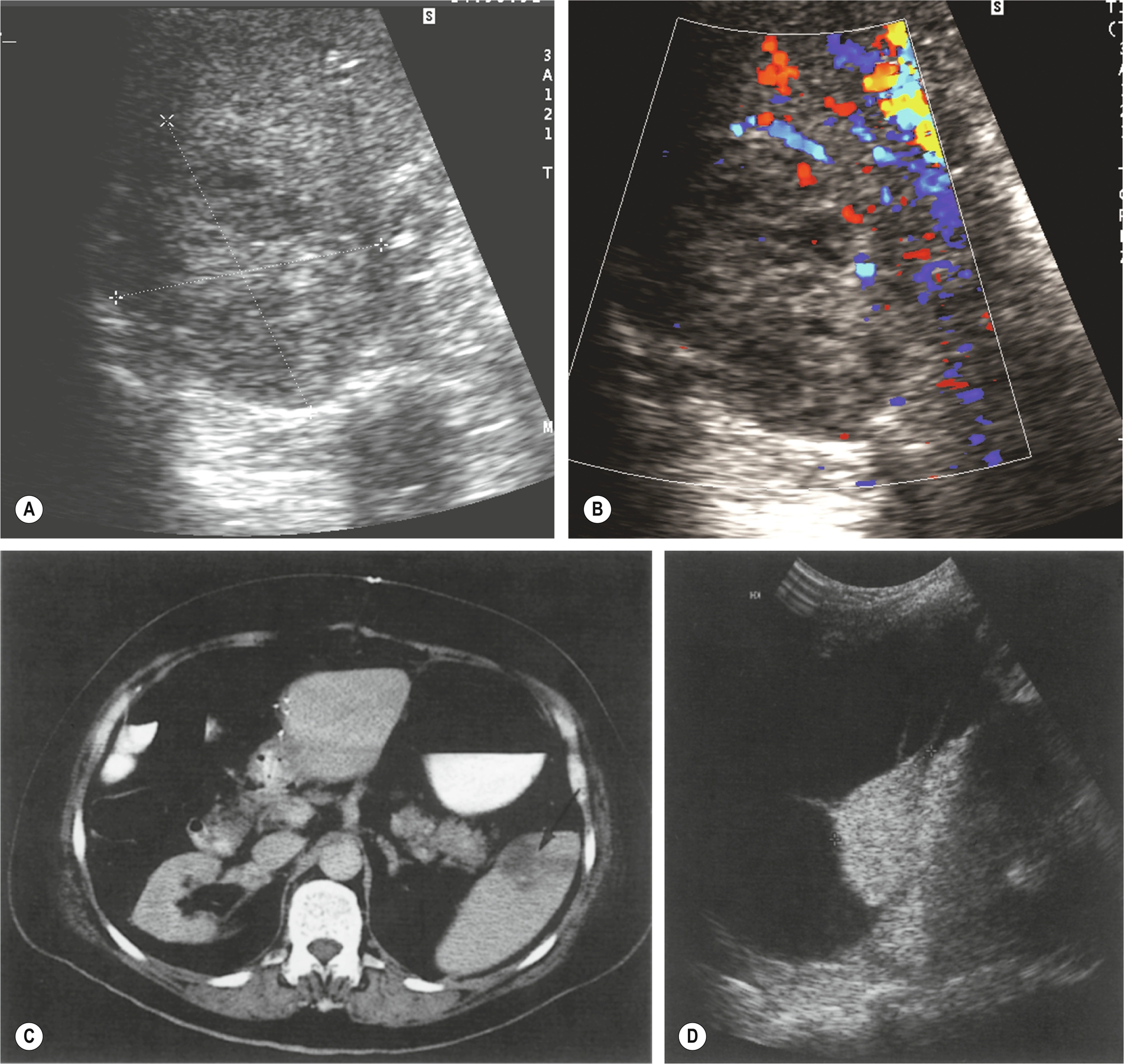

The main splenic artery and vein and their branches may be demonstrated at the splenic hilum (Fig. 5.1A–C). The spleen provides an excellent acoustic window to the upper pole of the left kidney, the left adrenal gland, and the tail of the pancreas.

Splenic Size

Ultrasound examination to assess the spleen for size is a common request because of physical examination having low sensitivity and specificity, especially with mild splenomegaly.1 The size and shape of the spleen can be highly variable between different people because of the variations in each person’s height, weight, and physique. When commenting upon size, it is important to consider the patient’s habitus when commenting on the size of the spleen. Generally, the spleen is similar in size to the left kidney; however, this must be used with caution.

The spleen should be measured along its length, from the superior-medial tip to the inferolateral aspect. A measurement of 5–12 cm is generally considered normal, although this is subject to variation in shape and the plane of measurement used. A small spleen is of doubtful clinical significance.2

Splenomegaly

Enlargement of the spleen is a highly non-specific sign associated with numerous conditions, the most common being infection, portal hypertension, hematological disorders, and neoplastic conditions (Box 5.1).

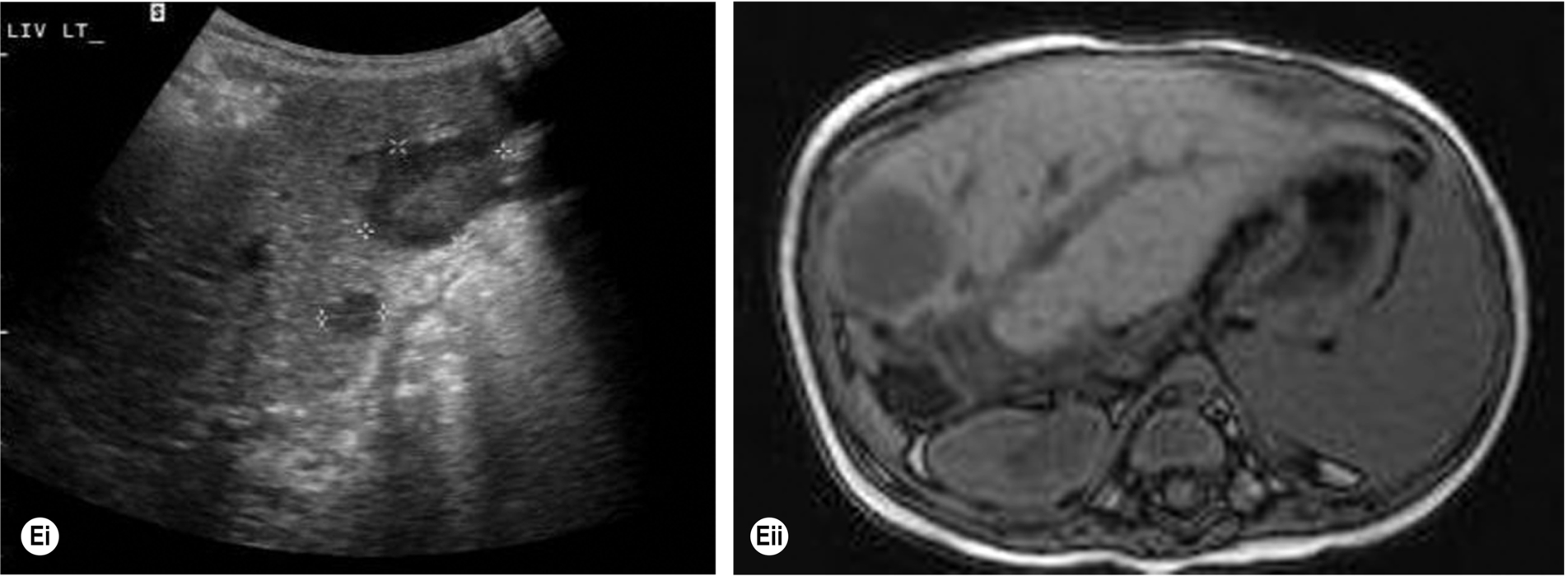

Measuring the length of the spleen is an adequate indicator of size for most purposes and provides a useful baseline for monitoring changes in disease status which is reproducible by the operator in subsequent scans and comparable to measurements obtained in cross-sectional imaging. Ultrasound is often the modality of choice in monitoring the spleen size because of lack of radiation and good operator reproducibility. A measurement of greater than 12 cm would be considered enlarged in most adults; however, as previously discussed, body size and type can impact the “normal” splenic size range. As the spleen enlarges, it extends downwards and medially. Its inferior margin becomes rounded (Figs. 5.1D–E, 5.2A), and it may extend below the left kidney and into the pelvis.

Although the cause of splenomegaly may not be obvious on ultrasound, the causes can be narrowed down by considering the clinical picture and by identifying other relevant appearances in the abdomen. For example, splenomegaly because of portal hypertension is frequently accompanied by other associated pathologic conditions such as cirrhotic liver changes, varices (Fig. 5.2B), or ascites. In cases of portal hypertension, it is important to assess the splenic vasculature to assess for varices at the hilum.

Splenic Anatomical Variants

Congenital anomalies of the spleen include persistent lobulation, accessory spleen (splenunculi), polysplenia, asplenia (absent), and wandering spleen. In a healthy individual, these anomalies can be seen in isolation or form part of an associated syndrome.

In the normal spleen, the borders are smooth and regular; however, in rare cases, the diaphragmatic surface of the spleen may appear lobulated or even completely septated. This appearance may give rise to diagnostic uncertainty, and Doppler may help establish the vascular supply and differentiate this from other masses in the LUQ or from scarring or infarction in the spleen.

The spleen may lie in an ectopic position, in the left flank or pelvis, or posterior to the left kidney. The ectopic (or wandering) spleen is situated on a long pedicle, allowing it to migrate within the abdomen. The significance of this rare condition is that the pedicle may twist, causing the patient to present acutely with pain from splenic torsion. Ultrasound demonstrates the enlarged, hypoechoic organ in the abdomen, with the absence of the spleen in its normal position.

Splenunculi

A small accessory spleen or splenunculus are common findings identified in around 10%-40% of the population at autopsy.3 They can be located anywhere in the abdomen, but the splenic hilum is the most common location, with around 80% found at this location.4 It is important to differentiate these from other pathologic conditions such as enlarged lymph nodes or possible adrenal nodule. It is not uncommon for splenic tissue to be found within the pancreatic tail, which can lead to diagnostic uncertainty, and in some cases, imaging such as positron emission tomography (PET) may be useful.4

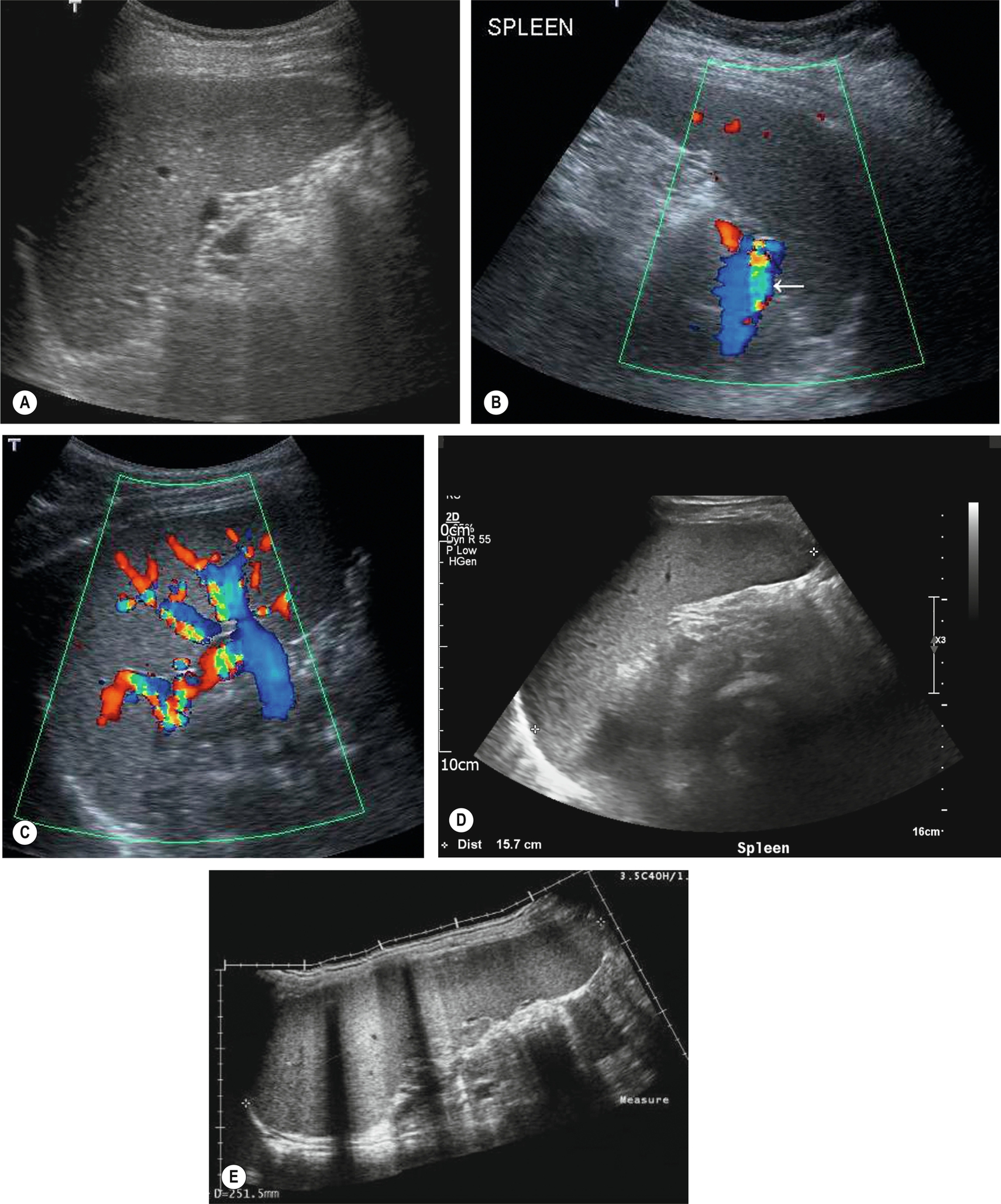

Splenunculi are typically small, well-defined ectopic nodules of splenic tissue and, therefore, are of similar ultrasound echotexture to the spleen (Fig. 5.2C–D) and rarely exceed 2 cm in diameter. Occasionally the vessels supplying the splenunculus can be seen using color Doppler, and in equivocal findings, contrast ultrasound can be used. Splenunculi enlarge under the same circumstances as those which cause splenomegaly and may also hypertrophy in post-splenectomy patients.

Polysplenia is the presence of two or more spleens rather than one “normal” spleen and can be linked to syndromes which can result in other abnormalities of the organs of the abdomen. In about 20% of cases of polysplenia syndrome, there is a link with situs inversus abdomonis.5

Pitfalls in Scanning the Spleen

- • In hepatomegaly, the left lobe of the liver may extend across the abdomen to the LUQ, displacing the spleen. This can give the appearance of a homogeneous, intrasplenic “mass” when the spleen is viewed coronally. A transverse scan at the epigastrium should demonstrate the extent of left hepatic enlargement and confirm its relationship to the spleen.

- • Splenunculi may be mistaken for enlarged lymph nodes at the splenic hilum. Color Doppler can confirm that the vascular drainage and supply are shared by the spleen.

- • The normal tail of the pancreas may mimic a perisplenic mass.

- • A left adrenal mass, or upper pole renal mass, may indent the spleen, making it difficult to establish its origin.

Malignant Splenic Disease

Lymphoproliferative Disorders

These are malignant hematologic conditions, comprising Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, leukemia, and myeloma.

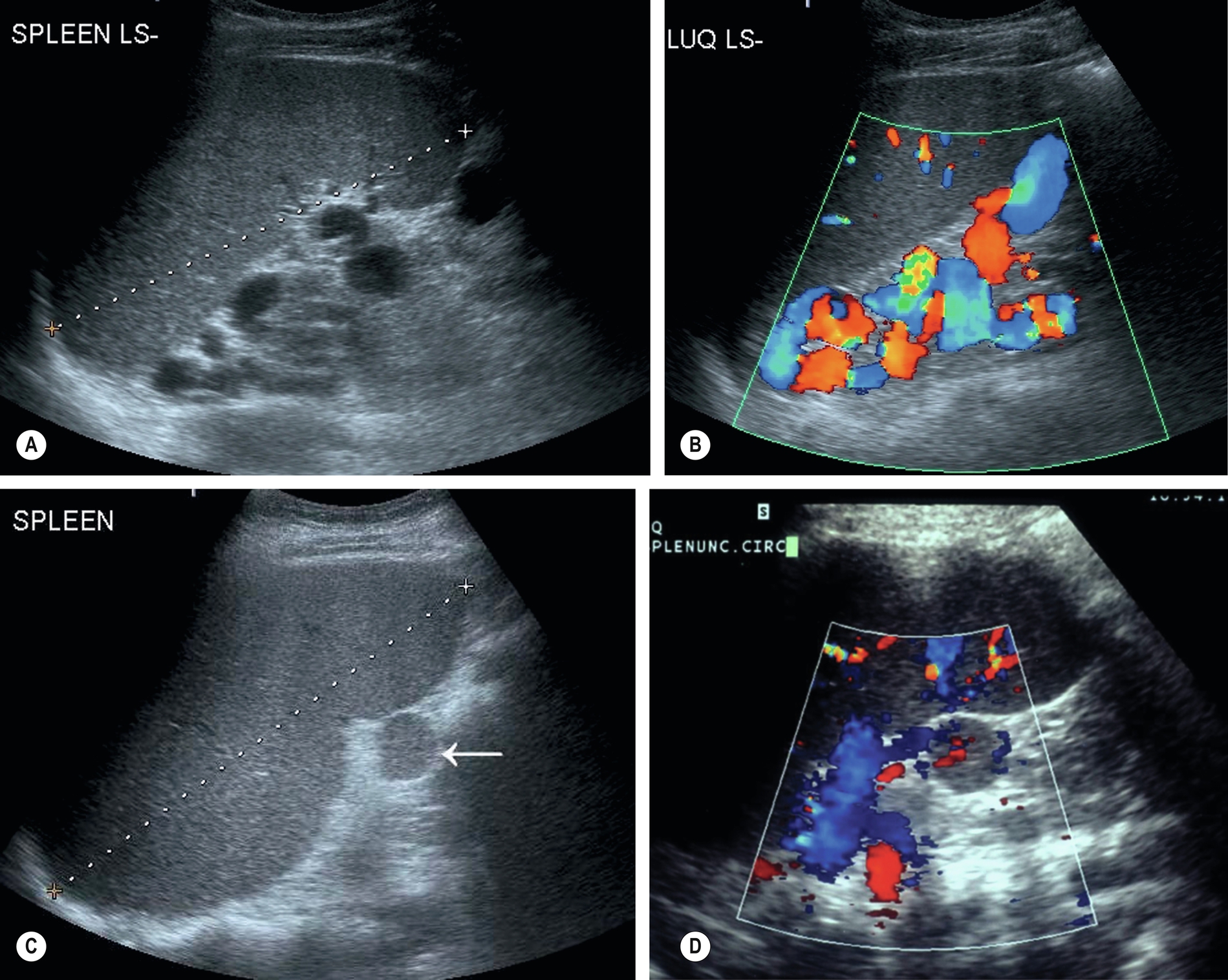

Lymphoma is the most common malignant disease affecting the spleen (Fig. 5.3). Malignant cells can infiltrate the spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and thymus and can also involve the liver, gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and other organs. Approximately 3% of malignant diseases are lymphomas. However, a primary splenic lymphoma is rare, constituting 2% of all lymphomas and 1% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas.6 A primary splenic lymphoma diagnosis is made when the lymphoma is contained within the spleen with no distant spread or only spread to the lymph nodes within the hilar region. Biopsy under ultrasound guidance can be performed and is considered a relatively safe procedure.

Splenic involvement because of malignant infiltration may be found in 30%–40% of patients with Hodgkin’s disease and 10%–40% of patients with non-Hodgkin’s in the initial stages of the disease.7

Lymphoma is also associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has given rise to a broad spectrum of lymphomatous conditions, which may be demonstrated on ultrasound and computed tomography (CT).8 These include masses in the liver, spleen, kidneys, adrenal gland, bowel, and other retroperitoneal and nodal masses. In addition, the increased use of immunosuppression in transplant patients and the increased survival in this group have also been the cause of an increased incidence of immunodeficiency-related lymphoma known as post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) (Fig. 5.3E).

Clinical Features and Management

Patients may present with a range of non-specific symptoms, which include painless lymph node enlargement particularly in the neck, armpit, and groin; anemia; general fatigue; weight loss; fever; sweating, including night sweats; and infections associated with decreased immunity. If the disease has spread to other organs, these may produce symptoms related to the organs in question. Prognosis depends upon the type of the disease, which must be determined histologically, and its stage.

Diagnosis is usually by biopsy of the lymph node or mass, and ultrasound is useful in guiding this procedure. In some cases, the excision of an affected node can be useful for diagnosis and treatment planning. CT is most frequently used for staging purposes and is superior to ultrasound in demonstrating lymphadenopathy, especially lymph nodes deeper within the abdomen, although ultrasound can be useful in helping to characterize focal lesions and detect renal obstruction.9 FDG-PET is increasingly useful in staging with a high diagnostic accuracy for identifying residual or recurrent tumor,10 and it can also help predict the patient’s response to therapy.

Depending on the type of lymphoma, chemotherapy regimens may be successful and if not curative, can cause remission for lengthy periods. High-grade types of lymphoma are particularly aggressive, with a poor survival rate.

Ultrasound Appearances

Patients may present with a varied and broad spectrum of appearances in lymphoma (Fig. 5.3). In many cases, the spleen is not enlarged and shows no acoustic abnormality.11 Lymphoma may produce a diffuse splenic enlargement with normal, hypo-, or hyperechogenicity. In patients with hematological conditions, it is important to consider splenic volume as a way to show the progression of disease.

Although lymphoma usually has a diffuse effect on the spleen, focal lesions may also be present. They tend to be hypoechoic and hypovascular and may be single or multiple. In larger lesions, the margins may be ill-defined, and the echo contents vary from almost anechoic to heterogeneous, often with increased through transmission. In such cases, they may be similar in appearance to cysts. However, the well defined capsule is absent in lymphoma, which has a more indistinct margin.12 Smaller lesions may be hyperechoic or mixed. Tiny lymphomatous foci may affect the entire spleen, making it appear coarse in texture.

Lymphadenopathy may be present elsewhere in the abdomen. If other organs, such as the kidney or liver, are affected, the appearances of mass lesions vary but are commonly hypoechoic or of mixed echo pattern.

A differential diagnosis of metastases should be considered in the presence of multiple solid hypoechoic splenic lesions, but most cases are because of lymphoma. In patients who are immunocompromised and at risk from PTLD, the main differential diagnosis with multiple hepatic or splenic lesions would be abscesses, as both PTLD and abscess may have similar acoustic characteristics.

Leukemia

Leukemia (literally meaning “white blood,” from the Greek) is characterized by an increased number of malignant white blood cells. Unlike lymphoma, which affects the lymphatic system, leukemia affects circulation. There are two main types: myeloid and lymphoid, which can be either acute or chronic. The bone marrow becomes infiltrated with malignant cells, which cause the blood to have increasing levels of immature blood cells.

Patients present with fatigue, anemia, recurrent infections, and a tendency to bleed internally. The patient’s inability to overcome infections may eventually lead to death.

Chemotherapy is successful in curing acute lymphoblastic leukemia in approximately half the patients and may induce remission in others. The long term prognosis is poor for other types of leukemia, although patients may survive for ten years or more with the slow-growing chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Leukemia produces diffuse splenic enlargement but rarely with any change in echogenicity. Abdominal lymphadenopathy may also be present.

Metastases

Metastatic deposits occur in the spleen relatively rarely than in the liver but are rarely isolated to the spleen and are generally because of more widespread disease. Autopsy reports an incidence of around 10%, although a proportion of these are microscopic and not amenable to radiological imaging.

The most commonly found splenic metastases on ultrasound are from lymphoma but may occur with any primary cancer. Intrasplenic metastases are more likely in later stage disease and favor pulmonary, osteosarcomas, soft tissue sarcomas, and renal cell carcinoma. Breast and ovarian cancers can also metastasize to the spleen, and melanoma must be considered, even when the disease is distant.

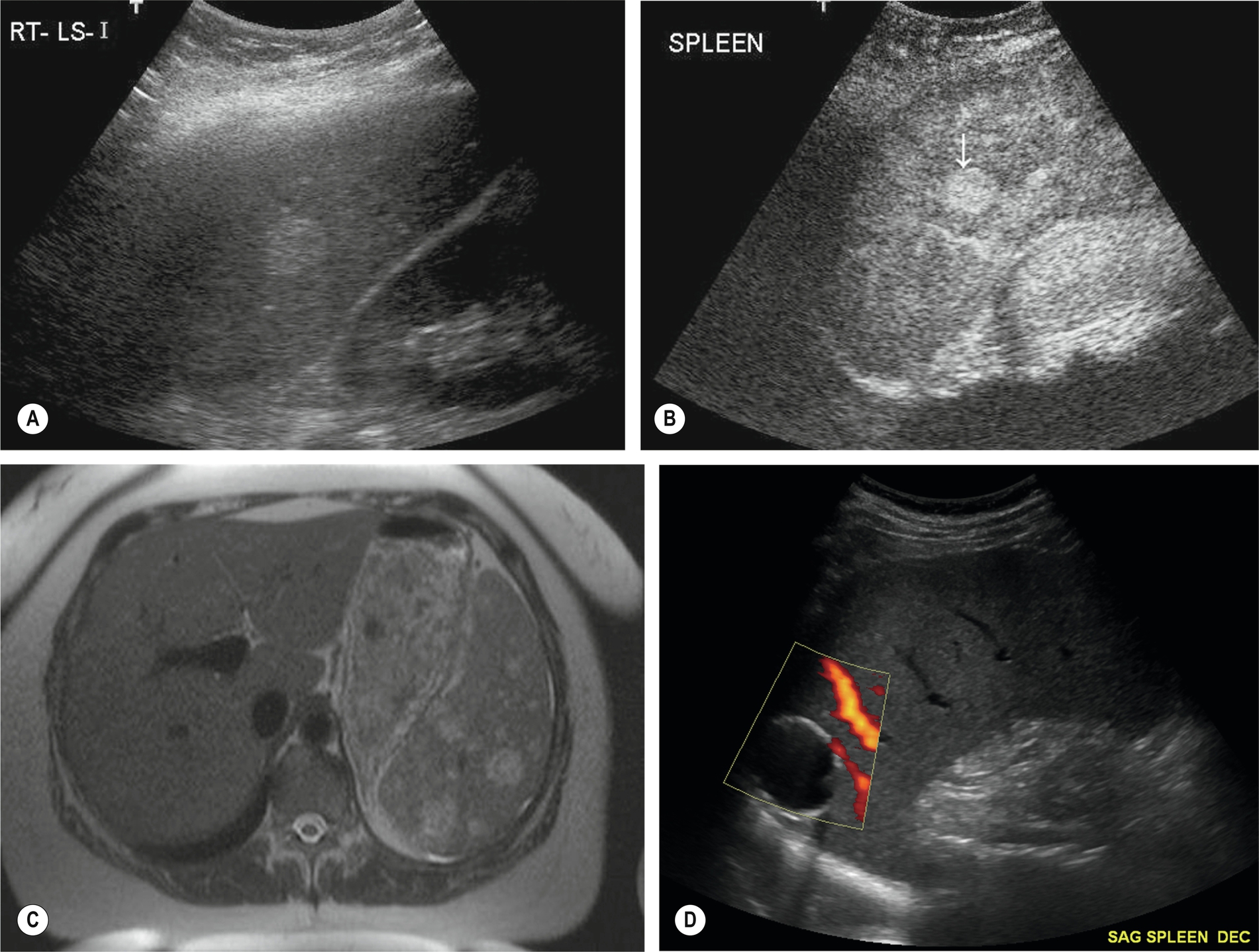

As with liver metastases, the ultrasound appearances vary enormously, ranging from hypo- to hyperechogenic or of a mixed pattern (Fig. 5.4). They may be solitary, multiple, or diffusely infiltrative, giving a coarse echo pattern. Metastases are usually solid in appearance. When cystic components are seen, this could indicate central necrosis or that the primary tumor is mucinous in nature (e.g., ovarian carcinoma).13

Benign Splenic Conditions

Focal lesions within the spleen are rare and are usually incidental findings when examining another organ.

Many benign focal lesions that occur in the spleen are of similar nature and ultrasound appearances to those in the liver.

Cysts

Splenic cysts have a relatively low incidence but are nevertheless the most common benign mass found in the spleen (Fig. 5.4D). Typically, cysts are rounded, with a thin wall with no internal echoes and posterior enhancement; occasionally thin septations may be seen, and also debris because of hemorrhage. Splenic cysts may occasionally be associated with autosomal dominant polycystic disease.

Other causes of cystic lesions in the spleen include post-traumatic cysts (liquefied hematoma) and hydatid cysts (Echinococcus granulosus parasite). Non-parasitic cysts are subdivided into congenital (e.g., Dermoid and epidermoid) and neoplastic cysts.13

As with hepatic cysts, hemorrhage may occur, causing LUQ pain. To avoid rupture, large cysts may be resected.

Abscess

Splenic abscesses usually result from bloodborne bacterial infection but can also be because of amoebic infection or post-traumatic or fungal infection. Patients with splenomegaly resulting from typhoid fever, malaria, and sickle cell disease are particularly predisposed to the formation of multiple pyogenic abscesses in the spleen.

Splenic abscesses are also particularly associated with immunosuppression, AIDS, and high-dose chemotherapy. Such patients become susceptible to invasive fungal infections, which can cause multifocal microabscesses in the liver and spleen.14 Patients present, as might be expected, with LUQ pain and fever.

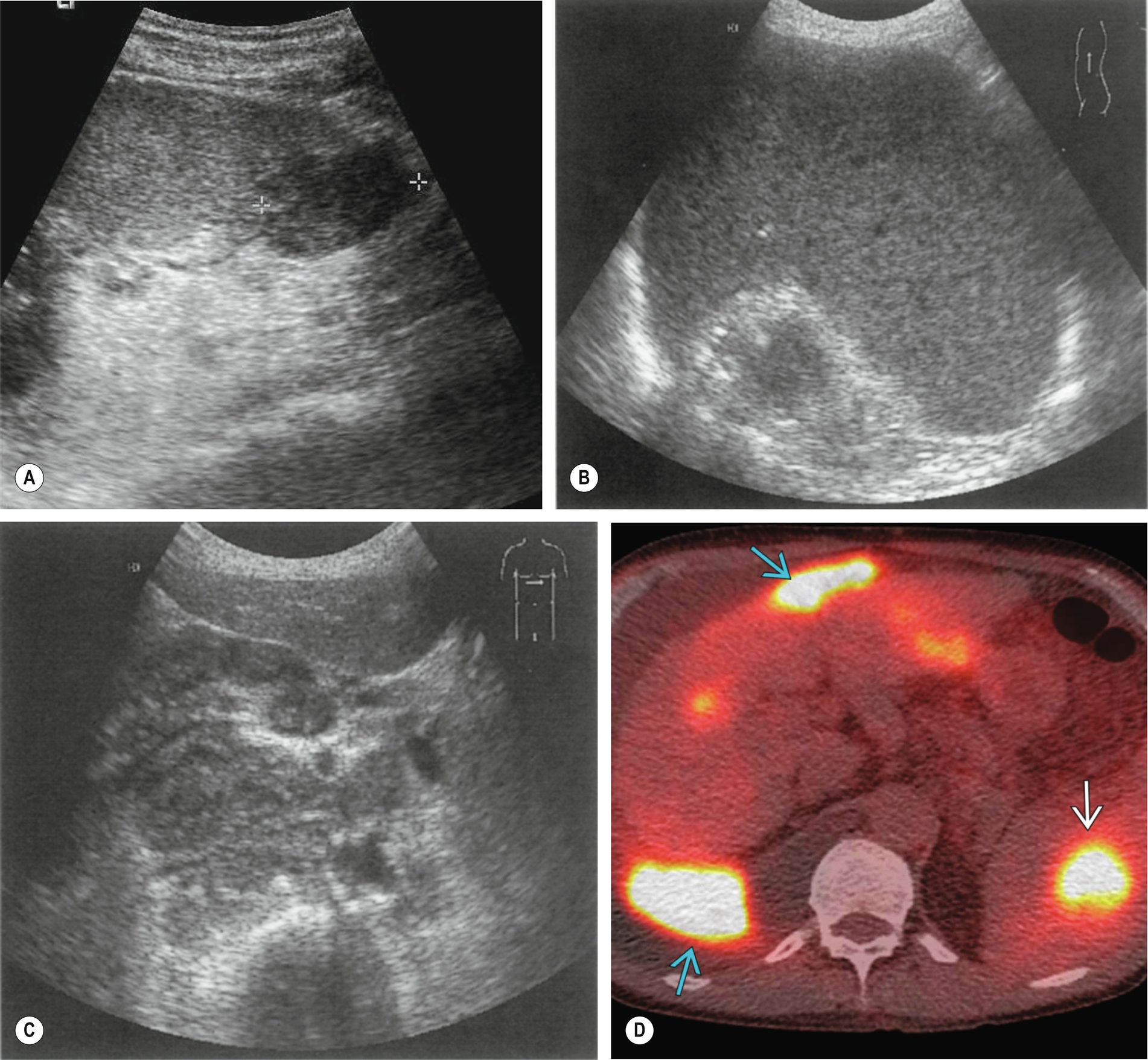

The ultrasound appearances are similar to liver abscesses; they may be single or multiple, hyperechoic, and homogeneous in the early stages, progressing to complex, fluid-filled structures with increased through transmission (Fig. 5.5A–B).

Splenic abscesses are frequently hypoechoic, and it may not be possible to differentiate abscess from lymphoma or metastases on ultrasound appearances alone. This applies both in cases of large solitary abscesses and in multifocal microabscesses. They may also contain gas, posing difficulties for diagnosis as the area may be mistaken for overlying bowel.

As with liver abscesses, percutaneous drainage with antibiotic therapy is the management of choice for solitary abscesses.

Calcification

Calcification may occur in the wall of old, inactive abscess cavities, forming granulomatous deposits. Calcification is often found secondary to changes of the splenic tissue because of tuberculosis (TB) and other infective processes. Other conditions causing calcification within the spleen include HIV, histoplasmosis, Pneumocystis carinii, and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare.13 Calcification is also associated with post-traumatic injury and may be seen around the wall of an old, resolving post-traumatic hematoma.

Conditions that predispose to the deposition of calcium in tissues, such as renal failure requiring dialysis, are also a source of splenic calcification.

Ultrasound findings include multiple hyperechoic lesions throughout the splenic tissue, some of which may display acoustic shadowing (Fig. 5.5C) and is sometimes referred to as “spotty spleen.”

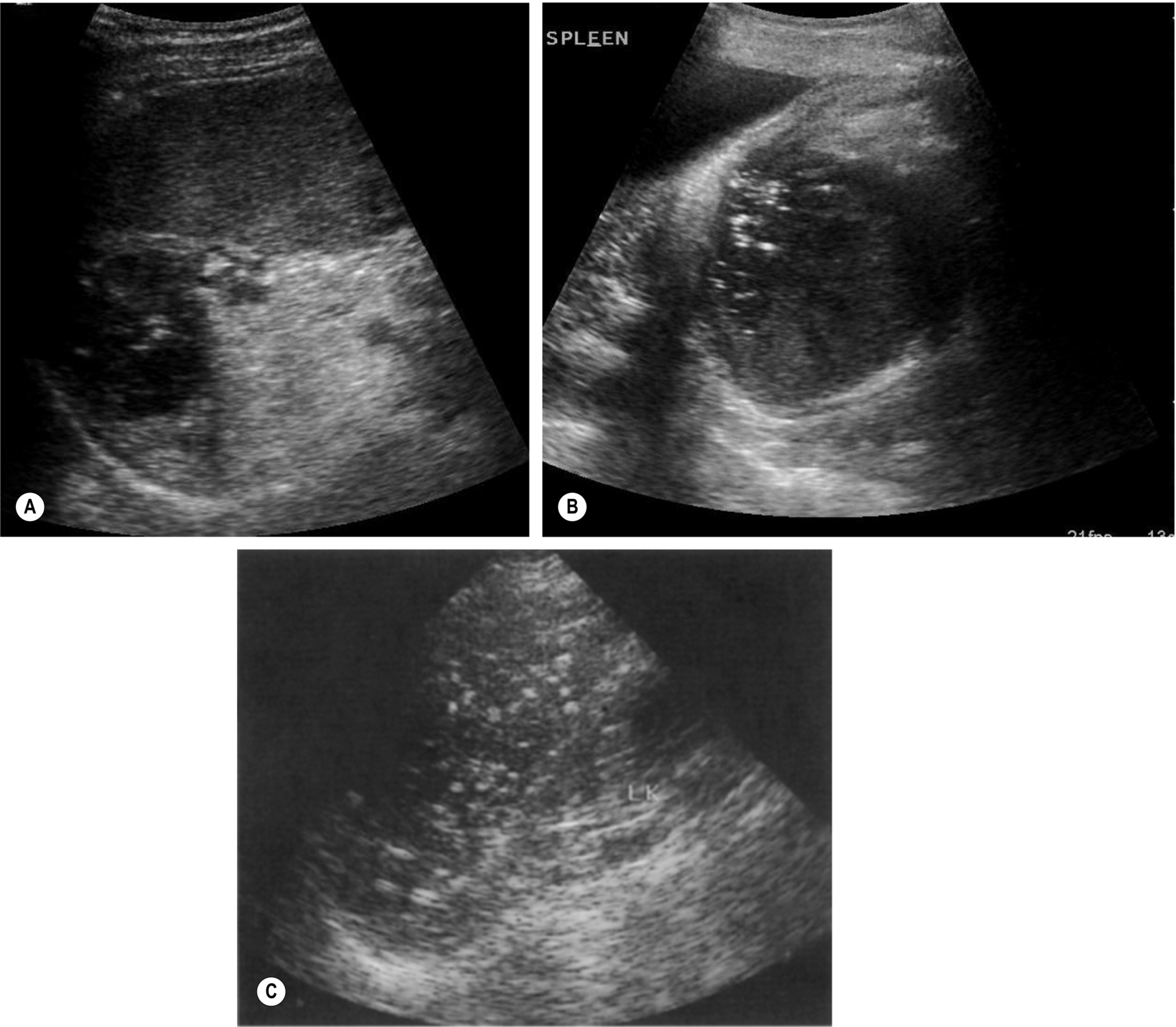

Hemolytic Anemia

Increased red blood cell destruction, or hemolysis, occurs under two circumstances: when there is an abnormality of the red cells – as in sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, or hereditary spherocytosis – or when a destructive process is at work, such as infection or autoimmune conditions. Fragile red cells are destroyed by the spleen, which becomes enlarged (Fig. 5.6A).

Sickle cell anemia is most prevalent in the black American and African populations. Progression of the disease leads to repeated infarcts in various organs, including the spleen, which may eventually become shrunken and fibrosed. Patients have (non-obstructive) jaundice because the increased destruction of red blood cells releases excessive amounts of bilirubin into the blood.

Vascular Abnormalities of the Spleen

A range of vascular neoplasms may occur in the spleen, most of which are relatively rare.15 These include hemangiomas (see above), lymphangioma, and the (malignant) angiosarcoma. A hamartoma is a rare hypervascular lesion that is found in the spleen and often appears as a solid lesion with cystic or necrotic areas and possible small areas of calcification. These lesions may be demonstrated on ultrasound, but a definitive diagnosis will usually require further imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and splenectomy may be performed in cases of a mass with atypical features.

Hemangioma

Benign hemangioma rarely occurs in the spleen. As in the liver, it is usually found as an incidental lesion on ultrasound. Multiple hemangiomata are rare and are usually seen as a solitary lesion. There are two types of hemangioma. The more common “capillary” hemangioma is well defined and hyperechoic compared to the splenic tissue. Color Doppler can be used, but machine settings will need to be altered to adequately demonstrate the low velocity flow; contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) can help view the blood supply of these lesions. A cavernous hemangioma may have a more atypical appearance on ultrasound, appearing more hypoechoic or of mixed echogenicity; partial calcification, and cystic components may also be seen.

Due to the variation in appearances, the presence of a hemangioma can give a conundrum, especially when found incidentally. The patient’s clinical history must be taken into consideration; differential diagnoses would include metastases, hematopoiesis, and lymphoma, and in these cases, CEUS, MRI, and CT may be required to aid diagnosis. In cases with a low clinical suspicion of malignancy, such lesions may be followed up with ultrasound and tend to remain stable in size (Fig. 5.6B).

Splenic Infarction

Splenic infarction is most commonly associated with sickle cell anemia, hematological malignancies, thrombophilia, and emboli because of endocarditis. It has also been reported more recently as a complication of hepatocellular carcinoma embolization.16 It usually results from thrombosis of one or more of the splenic artery branches. Because the spleen is supplied by both the splenic and gastric arteries, infarction tends to be segmental rather than global. Patients may present with LUQ pain, but not invariably.

Initially, the area of infarction is hypoechoic and usually wedge-shaped, solitary, and extending to the periphery of the spleen (Fig. 5.7). In the acute phase of infarction, B-mode ultrasound is not often useful, only identifying 50% of infarctions resulting in a high false-negative rate. The lesion may decrease in time and gradually fibrose, becoming hyperechoic. If the infarction is large, it may demonstrate reduced Doppler perfusion when compared to the normal splenic tissue, and CEUS may be particularly helpful in outlining the area of non-perfusion, allowing a definitive diagnosis and is represented as a triangular or slightly rounded area with the base extending to the splenic capsule. In rare cases of total splenic infarction (Fig. 5.7D), because of occlusion of the proximal main splenic artery, gray-scale sonographic appearances may be normal in the early stages.

Splenic Vein Thrombosis

This is frequently accompanied by portal vein thrombosis and results from the same disorders. The most common of these are pancreatitis and tumor thrombus. Color and spectral Doppler are an invaluable aid to the diagnosis, particularly when the thrombus is fresh and therefore echo-poor. Contrast agents may be administered if doubt exists over vessel patency. Splenic vein occlusion causes splenomegaly, and varices may be identified around the splenic hilum.

Splenic Artery Aneurysm

Although rare, splenic artery aneurysms are the third most common abdominal aneurysm, with aneurysms of the aorta and iliac arteries having greater incidence.17 On ultrasound, a cystic lesion may be seen around the splenic hilum, and color Doppler can often identify whether this is a vascular structure or whether this is a cystic lesion, such as pancreatic pseudocysts.

Splenic artery aneurysms are usually asymptomatic and are associated with pregnancy or liver disease with portal hypertension. It is only clinically significant if over 2 cm in diameter when the risk of rupture and fatal hemorrhage is present. Surgical resection and ligation was once the treatment of choice. However, now with growing acceptance for treating arterial aneurysms by endovascular methods, the emergence of endovascular ablative therapy has now become an option, although there is still not much evidence on the long term efficacy of this method.

Pseudoaneurysm

Pseudoaneurysm in the spleen occurs in a minority of cases following splenic trauma or in the context of chronic pancreatitis. An echo-free or “cystic” area may be observed, which demonstrates flow on color Doppler. To distinguish between a “true” aneurysm and pseudoaneurysm, the following features should be present in a true aneurysm: focal arterial disruption and inflammation at the location of an irregular vessel wall.17

Splenic Trauma

The presence of free fluid in the abdomen of a trauma victim as part of a FAST (focused abdominal sonography in trauma) scan should alert the sonographer to the strong possibility of organ injury following blunt abdominal injury. However, visualization of the laceration may be difficult to visualize on ultrasound, especially in the acute phase. A frank area of hemorrhage, easily identifiable on ultrasound, may not develop until later. The Royal College of Radiologists is clear that FAST scanning should not delay the transfer to CT and should be used as a triage tool in prioritizing patients, rather than as an alternative to CT.18

CT should be performed as the first imaging step in patients with blunt trauma, as it can also detect laceration to the gastrointestinal tract and other extra-visceral injury as well as assess the blood supply within the spleen (Fig. 5.8).

Iatrogenic splenic trauma has been known because of the ‘blind’ insertion of a drain in the case of left pleural effusion. Thankfully, the guidance from the British Thoracic Society and the National Patient Safety Agency to perform such procedures under ultrasound guidance, following proper training, has reduced such incidents.

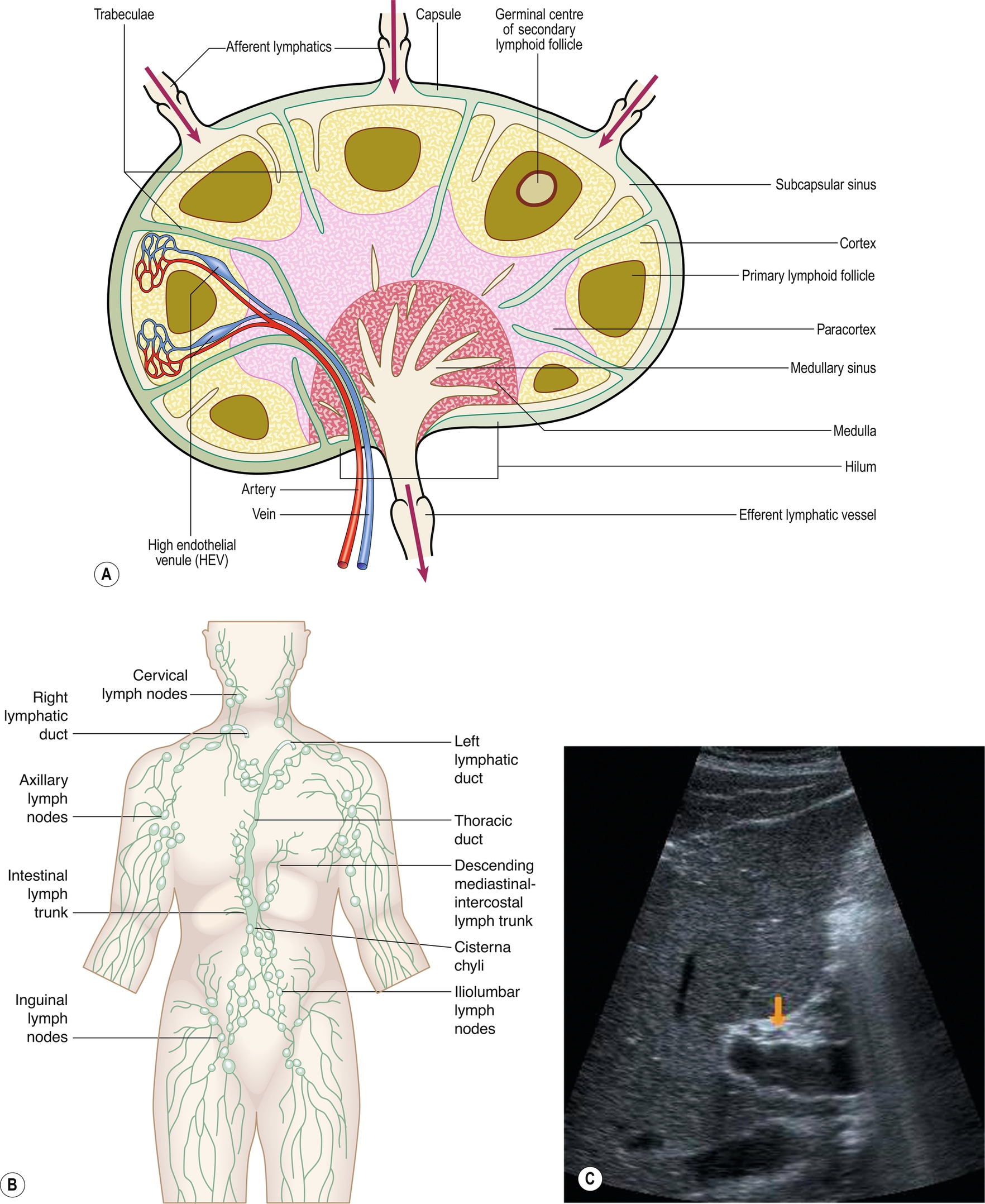

Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system is made up of a network of open-ended, low-pressure vessels, lymph nodes, and organs occluding the spleen but also other organs such as the tonsils and thymus, and these provide the route of return of interstitial fluid back into the circulatory system and also to fight infection.

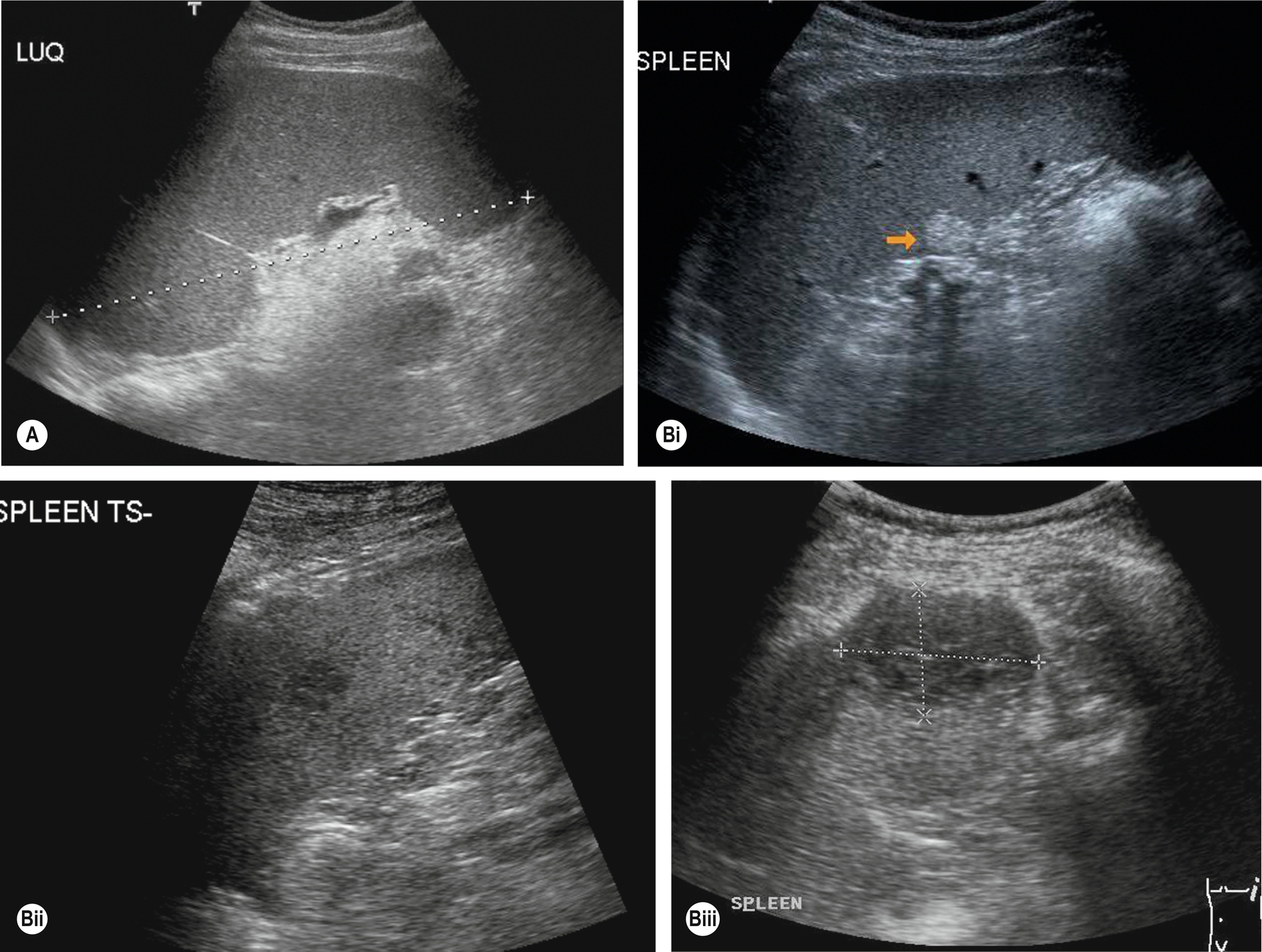

As lymphatic drainage is by one-directional flow back toward the heart, it is necessary to consider this when looking for spread from a known malignancy. Lymphatic circulation from the visceral organs will drain into the nodes between the lungs and around the intestines, and so this is often where the first evidence of malignant spread is seen. This lymphatic drainage will continue either along the right lymphatic duct or the thoracic duct (left side) and then enter the bloodstream via the subclavian veins in the neck, Palpable lymphadenopathy in the supraclavicular fossa may be identified in patients with a malignancy and there is evidence of metastatic spread via the lymphatic system (Fig. 5.9A–B).

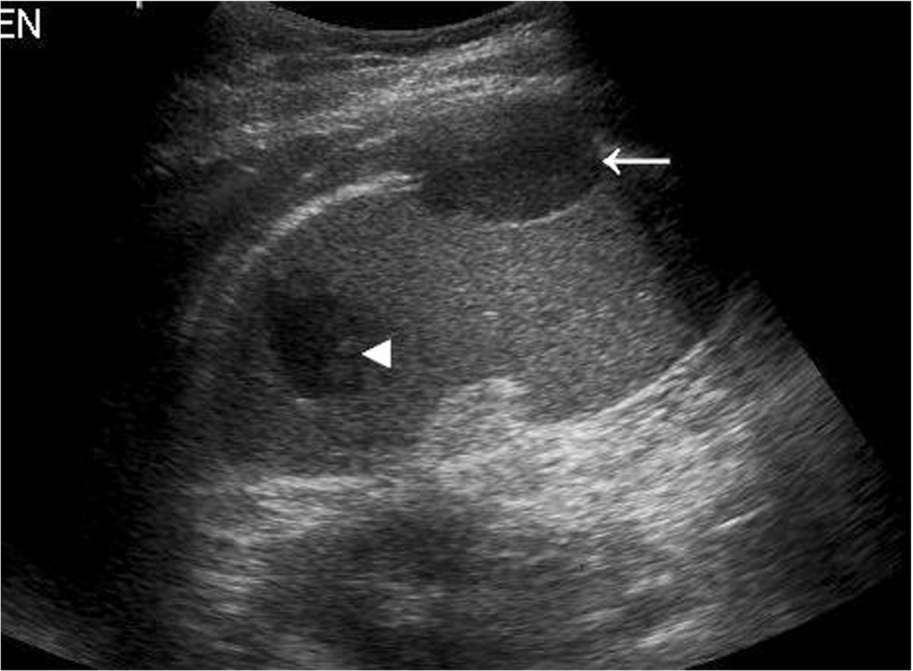

Normal lymph nodes are difficult to demonstrate on ultrasound, but in certain areas, such as at the porta hepatis, normal lymph nodes can be demonstrated using a suitable acoustic window, such as the liver (Fig. 5.9C), particularly in young and/or thin patients.

A normal lymph node is “bean” shaped and has a smooth, well defined capsule. Because of the tendency of abnormal nodes to be rounder in shape, lymph nodes should be measured at the narrowest point (short axis diameter). Although there can be some variation, a short axis measurement of greater than 10 mm would be considered abnormal. Reactive nodes can sometimes have a more lobular outline and can also be enlarged; clinical context is often useful in these cases. On ultrasound, the cortex of the normal lymph node is mildly hypoechoic with a hyperechoic central hilum which contains the lymphatic vessels and blood supply. This may be clearly seen in superficial nodes, but in deeper positions, the resolution may not be adequate. In these cases, the size and shape of the nodes will be the most important factors to determine abnormality. The search for lymphadenopathy should include the para-aortic and para-caval regions, the splanchnic vessels and epigastric regions, and the renal hilar (Fig. 5.9D–F). Ultrasound has a low sensitivity for demonstrating lymphadenopathy in the retroperitoneum, as bowel contents frequently obscure the relevant areas. CT and MRI can better define the extent of lymphadenopathy, particularly in the pelvis. PET is now commonly used to look for widespread lymphadenopathy.

The presence of lymphadenopathy is highly non-specific, being associated with a wide range of conditions, including malignancy, infections, and inflammatory disorders. Benign lymphadenopathy is commonly seen in conjunction with hepatitis and other inflammatory disorders such as pancreatitis, cholangitis, and colitis.19

Enlarged nodes are most often hypoechoic, rounded, or oval in shape and well defined in some cases infiltrating into adjacent structures or may combine to form large, lobulated masses. Nodes must be differentiated from other masses (such as gastrointestinal tract or other inflammatory masses), and Doppler is helpful here. Larger nodes display color or power Doppler radiating from a central hilum.

Lymphadenopathy occasionally causes obstructive jaundice because of compression of the common bile duct near the porta hepatis or venous thrombosis because of compression of the adjacent vein.

Lymphangioma

These are uncommon congenital malformations of the lymphatic system, which are usually diagnosed in the neonatal period or on prenatal sonography. They are predominantly cystic, frequently septated, and may be large (Fig. 5.10). They can compress adjacent organs and vessels, and their severity depends largely upon their location. They are most common in the neck (cystic hygroma) but can be found in various locations, including the abdomen,20 and are occasionally found in adults after a long asymptomatic period.