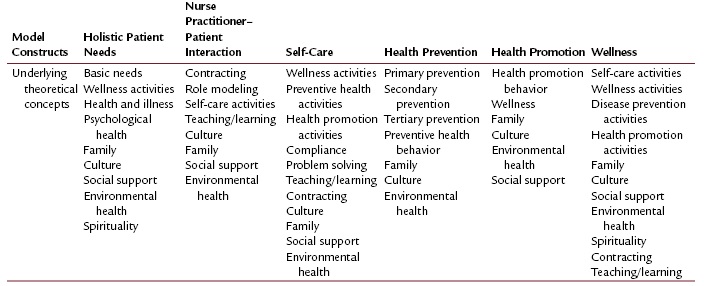

Conceptualizations of Advanced Practice Nursing

Cynthia Arslanian-Engoren

“Every artist was first an amateur.”

∼ Ralph Waldo Emerson

Concepts, models, and theories are used by advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) to elicit histories, perform physicals, plan treatment, evaluate outcomes, and develop interpersonal relationships, as well as to help patients and families improve their health, cope with illnesses, and die with dignity. All APRNs, regardless of their years of experience and practice, rely on common processes and language to communicate with colleagues about patient care and to explain clinical situations. As such, it is important that the nursing profession and APRNs understand the language of advanced practice nursing to communicate it to each other, clients, and stakeholders.

Understanding the conceptualization of advanced practice nursing, APRN practice, similarities and differences among APRNs, and how APRNs contribute to affordable, accessible, and effective care is central to actualizing a patient-centered, interprofessional healthcare system that maximizes patient outcomes and minimizes negative consequences. Conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing include models and theories that guide the practice of APRNs. The use of theory is fundamental to the sound progress in any practice discipline. Common language and mutually understood conceptual and theoretical frameworks support communication, guide practice, and are used to evaluate practice, education, policy, and research.

Such a foundation is essential for APRNs given the proposed changes in the US healthcare system, as seen in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 2010, the Consensus Model for APRN Regulation (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008), and The Future of Nursing Report 2020–2030 (National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine [NASEM], 2021). Other forces driving a common understanding of APRNs are the increasing numbers of programs offering the doctor of nursing practice (DNP) degree, accountable care organizations, and the promulgation of interprofessional competencies (Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative [CIHC], 2010; Health Professions Network Nursing and Midwifery Office, 2010; Interprofessional Education Collaborative [IPEC] Expert Panel, 2016), as well as recommendations to the United States Congress to increase funding for interprofessional education and practice (National Advisory Council on Nurse Education and Practice, 2015).

In addition to efforts in the United States, nursing associations, councils, and regulatory agencies in other countries have clarified, established, and/or regulated APRN roles and practice (Canadian Nurses Association [CNA], 2013, 2016a, 2016b; International Council of Nurses [ICN] Nurse Practitioner/Advanced Practice Nursing Network, 2020; Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, 2014). In countries in which APRN roles exist, in addition to studies of the distinctions among roles (Carryer et al., 2018; Gardner et al., 2013, 2016), APRN educational programs are being established, for example, in Israel (Kleinpell et al., 2014), mainland China (Wong, 2018), and Singapore (Ayre & Bee, 2014; see Chapter 5). Country-specific frameworks are being developed to clarify education, scope of practice, registration and licensing, and/or credentialing (Fagerström, 2009). Although contextual factors may differ from those in the United States, global opportunities exist for clarifying and advancing APRN practice specific to a country’s culture, health system, professional standards, and regulatory requirements. A sample of conceptual and theoretical models of APRN practice from various countries is presented in this chapter along with US and international conceptualizations of APRN roles.

Professional organizations with interests in licensing, accreditation, certification, and educational (LACE) issues regarding APRNs also operate from a conceptualization of advanced practice nursing, whether implicit or explicit. In this chapter, models promulgated by APRN stakeholder organizations that describe the nature of advanced practice nursing and/or differentiate between advanced and basic practice and selected models, including international, that have guided APRN practice are discussed. Problems associated with lack of a unified definition of advanced practice and imperatives for undertaking this important work exist. When practical, consensus on advanced practice nursing models should be beneficial for patients, society, and the profession. The APRN Consensus Model (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008) and core competencies of APRN practice brought needed conceptual clarity to the regulation of advanced practice nursing in the United States. However, variations in scope of practice still remain between states in the United States (Phillips, 2020) and around the world (Kleinpell et al., 2014). Additionally, work is still needed to differentiate basic and advanced nursing practice and the practice of APRNs from that of other disciplines. Therefore the purposes of this chapter are as follows:

- 1. Lay the foundation for thinking about the concepts underlying advanced practice nursing by describing the nature, purposes, and components of conceptual models.

- 2. Identify conceptual challenges in defining and operationalizing advanced practice nursing.

- 3. Describe selected conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing.

- 4. Make recommendations for assessing existing models and developing, implementing, and evaluating conceptual frameworks for advanced practice.

- 5. Outline future directions for conceptual work on advanced practice nursing.

It is important to note that, because of the dynamic and evolving nature of health care and nursing organizations’ activities in this arena, nationally and globally, readers are encouraged to consult the websites cited in this chapter for up-to-date information.

NATURE, PURPOSES, AND COMPONENTS OF CONCEPTUAL MODELS

A conceptual model is one part of the structure of nursing knowledge. Ranging from most abstract to most concrete, this structure consists of metaparadigms, philosophies, conceptual models, theories, and empirical indicators (Fawcett & Desanto-Madeya, 2013). Traditionally, key concepts in the metaparadigm of nursing are humans, the environment, health, and nursing (Fawcett & Desanto-Madeya, 2013).

Fawcett and Desanto-Madeya (2013) described a conceptual model as

a set of relatively abstract and general concepts that address the phenomena of central interest to a discipline, the propositions that broadly describe these concepts, and the propositions that state relatively abstract and general relations between two or more of the concepts. (p. 13)

In addition, they noted that a conceptual model is “a distinctive frame of reference … that tells [adherents] how to observe and interpret the phenomenon of interest to the discipline” and “provide[s] alternative ways to view the subject matter of the discipline; there is no ‘best’ way” (Fawcett & Desanto-Madeya, 2013, p. 13). Although there is no best way to view a phenomenon, evolving a more uniform and explicit conceptual model of advanced practice nursing benefits patients, nurses, and other stakeholders (Institute of Medicine, 2011) by facilitating communication, reducing conflict, and ensuring consistency of advanced practice nursing, when relevant and appropriate, across APRN roles, and by offering a “systematic approach to nursing research, education, administration, and practice” (Fawcett & Desanto-Madeya, 2013, p. 15).

Models may help APRNs articulate professional role identity and function, serving as a framework for organizing beliefs and knowledge about their professional roles and competencies, providing a basis for further development of knowledge. In clinical practice, APRNs use conceptual models in the delivery of their holistic, comprehensive, and collaborative care (Carron & Cumbie, 2011; Dunphy, Winland-Brown, Porter, Thomas & Gallagher, 2011; Elliott & Walden, 2015; Musker, 2011). Models may also be used to differentiate among and between levels of nursing practice—for example, between staff nursing and advanced practice nursing (Gardner et al., 2013) and between clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), nurse-midwives (CNMs), and nurse practitioners (NPs; Begley et al., 2013).

Conceptual models are also used to guide research and theory development by focusing on a given concept or examining the relationships among select concepts to elucidate testable theories. For example, Gullick and West (2016) evaluated Wenger’s community of practice framework to build research capacity and productivity for CNSs and NPs in Australia. Faculty, in the preparation of students for APRN roles, use conceptual models to plan curricula, to identify important concepts and their relationships, and to make choices about course content and clinical experiences (Perraud et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2010).

Fawcett and Graham (2005) and Fawcett et al. (2004) have challenged us to think about conceptual questions of advanced practice:

- ■ What do APRNs do that makes their practice “advanced”?

- ■ To what extent does incorporating activities traditionally done by physicians or other healthcare professionals qualify nursing practice as “advanced”?

- ■ Are there nursing activities that are also advanced?

Because direct clinical practice is viewed as the central APRN competency, this begs the question: What does the term clinical mean? Does it refer only to hospitals or clinics? These questions are becoming more important given the APRN Consensus Model and given the role that APRNs are expected to play across the continua of health care as a result of ongoing changes to healthcare legislation. From a regulatory standpoint, the emphasis on a specific population as a focus of practice will lead, when appropriate, to reconceptualizing curricula to ensure that graduates are prepared to succeed in new or revised certification examinations. Hamric (2014) has noted that although some APRN competencies (e.g., collaboration) may be performed by nurses in other roles, the expression of these competencies by APRNs is different (see Chapter 3). For example, although all nurses collaborate, APRNs are expected to lead, facilitate, and role model collaboration. In addition, a unique aspect of APRN practice is that APRNs are authorized to initiate referrals and prescribe treatments that are implemented by others (e.g., physical therapy). Innovations and reforms arising from changes in healthcare legislation will ensure that APRNs are explicitly engaged in the delivery of care across care settings, including in nursing clinics and palliative care settings, and as full participants in interprofessional teams. Changes in regulations and in the delivery of health care may be the impetus that leads to new or revised conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing (e.g., defining theoretical and evidence-based differences between the care provided by APRNs and other providers and clinical staff, the role of APRNs in interprofessional teams, and specialization and subspecialization in advanced practice nursing). Working together, nursing leaders and health policymakers will be able to design a healthcare system that delivers high-quality care at reasonable cost, based on disciplinary and interdisciplinary competencies, outcomes, effectiveness, and efficacy.

In addition to a pragmatic reevaluation of advanced practice nursing concepts based on the evolution of APRN regulation and healthcare reform, important theoretical questions are being raised about the conceptualization of advanced practice nursing. Issues range from the epistemologic, philosophic, and ontologic underpinnings of advanced practice (Arslanian-Engoren et al., 2005) and the extent to which APRNs are prepared to apply nursing theory to their practices (Algase, 2010; Arslanian-Engoren et al., 2005; Karnick, 2011) to the questions about the nature of advanced practice knowledge, discerning the differences between and among the notions of specialty, advanced practice, and advancing practice (Allan, 2011; Christensen, 2009, 2011; MacDonald et al., 2006; Thoun, 2011).

In summary, questions arising from a changing health policy landscape and from theorizing about advanced practice nursing underscore the need for well-thought-out, robust conceptual models to guide APRN practice. Conceptual clarity of advanced practice nursing, what it is and is not, is important not only for patients and those in the nursing profession but also for interprofessional education (CIHC, 2010; Health Professions Network Nursing and Midwifery Office, 2010; IPEC Expert Panel, 2016) and practice (American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology [AANA], 2018). Conceptual clarity of advanced practice nursing will also inform the creation of accountable care organizations and support efforts to build teams and systems in which effective communication, collaboration, and coordination will lead to high-quality care and improved patient, institutional, and fiscal outcomes.

CONCEPTUALIZATIONS OF ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING: PROBLEMS AND IMPERATIVES

Despite the usefulness and benefits of conceptual models, conceptual confusion and uncertainty remain regarding advanced practice nursing. One noted issue is the lack of a well-defined and consistently applied core stable vocabulary used for model building. Despite progress, this challenge remains. For example, in the United States advanced practice nursing is the term that is used, but the ICN and CNA use the term advanced nursing practice. Considerable variation is noted between the conceptual definition of advanced practice nursing and that of advanced nursing practice as used in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom (Stasa et al., 2014). Adding to this opacity is the use of the term advanced practitioner to describe the role of non-APRN experts in the United Kingdom and internationally (McGee, 2009). The role and functions of APRNs need to be clearly and consistently conceptualized, which is challenging when different terms are used to describe APRNs. For example, the state of Iowa in the United States uses the term advanced registered nurse practitioner to describe all four advanced practice nursing roles, whereas the state of Virginia uses the term licensed nurse practitioner to describe NPs, CNMs, and certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs).

The APRN Consensus Model (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008) represents a major step forward in promulgating a uniform definition of advanced practice in the United States for the purpose of regulation. However, the lack of a core vocabulary continues to make comparisons difficult because the conceptual meanings vary. Competencies are more commonly used to describe concepts of APRN practice, but reflection on and discussion of other terms such as roles, hallmarks, functions, activities, skills, and abilities continue and may contribute to the urgent need for clarification of conceptual models and a common language.

Few models of APRN practice address nursing’s metaparadigm (person, health, environment, nursing) comprehensively. The problem in comparing, refining, or developing models is that concepts are often used without universal meaning or consensus and, occasionally, with no or inconsistent definitions. It is rightly anticipated that conceptual models of the field and its practice change over time. However, the evolution of advanced practice nursing and its comprehension by nurses, policymakers, and the public will be enhanced if scholars and practitioners agree on the use and definition of fundamental concepts of APRN practice.

Another challenge is the paucity of conceptual models describing the practice and outcomes of APRNs. Although the numbers of models are increasing, they remain small. Further compounding this issue is the scarcity of international and global models of APRN practice. Within the United Arab Emirates, the role of the APRN is emerging along with a road map for successful implementation (Behrens, 2018); though encouraging, no formal APRN model has been put forth to date. Models are needed that address the diverse health and cultural needs of individuals, families, and communities worldwide.

Another issue is a lack of clarity in the conceptualizations that differentiate the clinical practice of APRNs from that of registered nurses (RNs). Conceptual models can help identify key concepts and variables that distinguish the focus, levels of practice, and outcomes between and among nurses with different levels and types of academic preparation and specialty certification.

Of additional importance is clarifying and distinguishing the differences in practice of APRNs and physician colleagues. Some graduate APRN students may struggle with this issue as part of role development. The lack of conceptual clarity is apparent in advertisements that invite both NPs and physician assistants to apply for the same position. Organized medicine continues to expend resources trying to limit or discredit advanced practice nursing, even as some physician leaders work on behalf of advocating for APRNs. Barriers to APRNs’ ability to practice to the full extent of their education and training as recommended by NASEM’s Future of Nursing 2020–2030 report (2021) may be the result of lack of conceptual clarity between nursing at the advanced practice level and the practice of medicine. To this end, the philosophic underpinnings of conceptual models of APRN practice need explication.

The emphasis on interprofessional education and practice is another issue in need of clarification. Interprofessional education and practice are central to accountable, collaborative, coordinated, and high-quality care. Graduate education of APRNs alongside other health professionals is beginning to take place. For example, at the University of Michigan, an interprofessional clinical decision-making course with graduate students from nursing (APRN students), pharmacy, dentistry, medicine, and social work is one of the first of its kind in the nation. Students learn together and from each other about their roles, preparation, and disciplinary foci (Sweet et al., 2017). The development of interprofessional competencies for health professionals (CIHC, 2010; Health Professions Network Nursing and Midwifery Office, 2010; IPEC Expert Panel, 2016) indicates the need for high-functioning interprofessional teams of healthcare experts to maximize patient outcomes. The existence of interprofessional competencies and emergence of promising conceptualizations of interprofessional work are critical contextual factors for elucidating and advancing conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing (Barr et al., 2005; Reeves et al., 2011). Conceptual models for APRN practice on interprofessional teams are needed to explicate the unique and critical contributions of APRNs to patient outcomes and system resources.

Among many imperatives for reaching a conceptual consensus on advanced practice nursing, most important are the interrelated areas of policymaking, licensing and credentialing, and practice, including competencies. In the policymaking arena, for example, not all APRNs are eligible to be reimbursed by insurers, and even those activities that are reimbursable are often billed ”incident to” a physician’s care, rendering the work of APRNs invisible (see Chapter 19). The APRN Consensus Model (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008), the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010), and NASEM’s The Future of Nursing 2020–2030 (2021) call for changes to enable APRNs to work within their full scope of practice will make it easier for US policymakers to recommend and adopt changes to policies and regulations that now constrain APRN practice, eventually making the contributions of APRNs to quality care visible and reimbursable. Agreement on vocabulary and concepts such as competencies that are common to all APRN roles will maximize the ability of APRNs to work within their full scope of practice.

Although some progress has been made, there are compelling reasons for continuing dialogue and activity aimed at clarifying advanced practice nursing and the concepts and models that help stakeholders understand the nature of APRN work and the contributions of APRNs. Reaching consensus on concepts and vocabulary will serve theoretical, practical, and policymaking purposes. As the work of healthcare reform and implementing interprofessional competencies, education, and practice moves forward, there will be opportunities for the profession to conceptualize advanced practice nursing more clearly. Box 2.1 presents outcomes that come from clarification and consensus on conceptualization of the nature of advanced practice nursing.

CONCEPTUALIZATIONS OF ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING ROLES: ORGANIZATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

Practice with individual clients or patients is the central work of the field; it is the reason for which nursing was created. The following questions are the kinds of questions a conceptual model of advanced practice nursing should answer:

- ■ What is the scope and purpose of advanced practice nursing?

- ■ What are the characteristics of advanced practice nursing?

- ■ Within what settings does this practice occur?

- ■ How do APRNs’ scopes of practice differ from those of other providers offering similar or related services?

- ■ What knowledge and skills are required?

- ■ How are the knowledge and skills different from those of other providers?

- ■ What patient and institutional outcomes are realized when APRNs deliver care? How are these outcomes different from those of other providers?

- ■ When should healthcare systems employ APRNs, and what types of patients particularly benefit from APRN care?

- ■ For what types of pressing healthcare problems are APRNs a solution in terms of improving outcomes, quality of care, and cost-effectiveness?

- ■ How are diversity and social determinants of health addressed in APRN conceptual models?

- ■ What changes or revisions are needed to include?

- ■ Are outcomes improved when APRNs deliver care guided by models that include these key concepts?

Of the conceptual models presented in this chapter, some are more narrowly focused than others, and some are more homogeneous or mixed with respect to the phenomenon studied. Still other models explain systems and the relationships between and among systems. All of these foci are important, depending on the purposes to be served. However, in the development of conceptual models, the phenomenon to be modeled must be carefully defined. For example, a model may encompass the entire field of advanced practice nursing or be confined to distinctive concepts (e.g., collaborative practice between APRNs and physicians or the difference between APRN practice and the practice of non-APRN nurses). If a phenomenon and its related concepts are not clearly defined, the model could be so inconsistent as to be confusing or so broad that its effect will be diluted.

In addition to describing concepts and how they are related, assumptions about the philosophy, values, and practices of the profession should be reflected in conceptual models. The discussion of conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing is guided by these assumptions:

- 1. Each model, at least implicitly, addresses the four elements of nursing’s metaparadigm: persons, health and illness, nursing, and the environment.

- 2. The development and strengthening of the field of advanced practice nursing depend on professional agreement regarding the nature of advanced practice nursing (a conceptual model) that can inform APRN program accreditation, credentialing, and practice.

- 3. APRNs meet the needs of society for advanced nursing care.

- 4. Advanced practice nursing will reach its full potential to the extent that foundational conceptual components of any model of advanced practice nursing framework are delineated and agreed on.

Consensus Model for Advanced Practice Registered Nurse Regulation

In 2004, an APRN Consensus Conference was convened to achieve consensus regarding the credentialing of APRNs (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008; Stanley et al., 2009) and the development of a regulatory model for advanced practice nursing. Independently, the APRN Advisory Committee for the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) was charged by the NCSBN Board of Directors with a similar task of creating a future model for APRN regulation and, in 2006, disseminated a draft of the APRN Vision Paper (NCSBN, 2006), a document that generated debate and controversy. Within a year, these groups came together to form the APRN Joint Dialogue Group, with representation from numerous stakeholder groups, and the outcome was the APRN Consensus Model (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008).

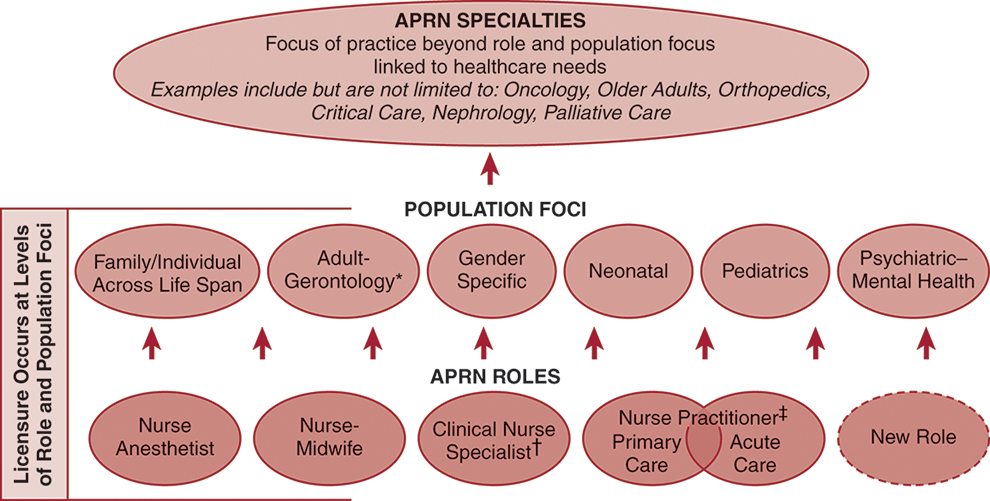

The APRN Consensus Model includes important definitions of roles, titles, and population foci. Furthermore, it defines specialties and describes how to make room for the emergence of new APRN roles and population foci within the regulatory framework. A timeline for adoption and strategies for implementation were put forth, and progress has been made in these areas (see Chapter 20 for further information; only the model is discussed here). Fig. 2.1 depicts the components of the APRN Consensus Model, the four recognized APRN roles and six population foci. The term advanced practice registered nurse refers to all four APRN roles. An APRN is defined as a nurse who meets the following criteria (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008):

- ■ Completes an accredited graduate-level education program preparing them for one of the four recognized APRN roles and a population focus (see discussion in Chapter 3)

- ■ Passes a national certification examination that measures APRN role and population-focused competencies and maintains continued competence by national recertification in the role and population focus

- ■ Possesses advanced clinical knowledge and skills preparing them to provide direct care to patients; the defining factor for all APRNs is that a significant component of the education and practice focuses on direct care of individuals

- ■ Builds on the competencies of RNs by demonstrating greater depth and breadth of knowledge and greater synthesis of data by performing more complex skills and interventions and by possessing greater role autonomy

- ■ Is educationally prepared to assume responsibility and accountability for health promotion and/or maintenance, as well as the assessment, diagnosis, and management of patient problems, including the use and prescription of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions

- ■ Has sufficient depth and breadth of clinical experience to reflect the intended license

- ■ Obtains a license to practice as an APRN in one of the four APRN roles

The definition of the components of the APRN Consensus Model begins to address some of the questions about advanced practice posed earlier in this chapter. An important agreement was that providing direct care to individuals is a defining characteristic of all APRN roles. This agreement affirms a position long held by original and current editors of this text—that when there is no direct practice component in the role, one is not practicing as an APRN. It also has important implications for LACE and for career development of APRNs.

Graduate education for the four APRN roles is described in the Consensus Model document (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008). It must include completion of at least three separate, comprehensive graduate courses in advanced physiology and pathophysiology, physical health assessment, and advanced pharmacology (the “three Ps”), consistent with requirements for the accreditation of APRN education programs. In addition, curricula must address three other areas—the principles of decision making for the particular APRN role, preparation in the core competencies identified for the role, and role preparation in one of the six population foci.

The Consensus Model asserts that licensure must be based on educational preparation for one of the four existing APRN roles and a population focus, that certification must be within the same area of study, and that the four separate processes of LACE are necessary for the adequate regulation of APRNs (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008; see Chapter 20). The six population foci displayed in Fig. 2.1 include the individual and family across the life span as well as adult/gerontologic, neonatal, pediatric, women’s health/gender-specific, and psychiatric/mental health populations. Preparation in a specialty, such as oncology or critical care, cannot be the basis for licensure. Specialization

indicates that an APRN has additional knowledge and expertise in a more discrete area of specialty practice. Competency in the specialty area could be acquired either by educational preparation or experience and assessed in a variety of ways through professional credentialing mechanisms (e.g., portfolios, examinations).

(APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008, p. 12)

This was a critical decision for the group to reach, given the numbers of specialties and APRN specialty examinations in place when the document was prepared.

Even with this brief overview of the APRN Consensus Model, one sees how this model advanced the conceptualization of advanced practice nursing. It is helpful for many reasons. First, for the United States, it affirms that there are four APRN roles. Second, it is advancing a uniform approach to LACE and advanced practice nursing that has practical and policymaking effects, including better alignment between and among APRN curricula and certification examinations. Furthermore, it addresses the issue of differentiating between RNs and APRNs and has been foundational to differentiate among nursing roles. By addressing the issue of specialization, the model offers a reasoned approach for the following: (1) avoiding confusion from a proliferation of specialty certification examinations; (2) ensuring that, because of a limited and parsimonious focus (four roles and six populations), there will be sufficient numbers of APRNs for the relevant examinations to ensure psychometrically valid data on test results; and (3) allowing for the development of new APRN roles or foci to meet society’s needs.

Although there are a number of noted strengths of the Consensus Model, there are also limitations. First, competencies that are common across APRN roles are not addressed beyond defining an APRN and indicating that students must be prepared “with the core competencies for one of the four APRN roles across at least one of the six population foci” (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008, p. 10). The model leaves it to the different APRN roles to develop their own core competencies.

In addressing specialization, the model also leaves open the issue of the importance of educational preparation, in addition to experience, for advanced practice in a specialty, which is of particular importance to the CNS role. Additionally, Martsolf and colleagues (2020) recently raised concerns regarding the misalignment between specialty NP education, certification, and practice location and called for an evaluation of the policy and practice implications of the Consensus Model, along with an examination of the scope and scale of NP misalignment within healthcare systems.

Two years after the 2004 APRN consensus conference, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN, 2006) put forth “The Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice.” The Essentials established the DNP, the highest practice degree and the preferred preparation for specialty nursing practice. The AACN called for doctorate-level preparation of APRNs by the year 2015. DNP preparation for entry to practice has been endorsed by the Council on Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational Programs (2019), the National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists (NACNS, 2015), and the National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties (NONPF, 2015). However, the American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM, 2019) has not endorsed the DNP as a requirement for entry into practice for CNMs, instead supporting the completion of a graduate degree program requirement for certification and entry into clinical practice.

Although experience in an area is certainly a factor that leads to the emergence of new specialties, experience alone may be insufficient for the APRN who specializes in oncology or critical care (or another specialty) to achieve desired outcomes in timely and cost-effective ways. These are specialties in which the population’s needs are many and complex and the scope of research knowledge is similarly broad and deep. These are important areas of conceptualization that need to be addressed by the American Nurses Association (ANA) and specialty professional nursing organizations, rather than by a group with a regulatory focus.

Numerous efforts are under way to implement this model in the United States. The NCSBN has an extensive toolkit to help educators, APRNs, and policymakers implement the APRN regulatory model (NCSBN, 2015). The work undertaken to produce the APRN Consensus Model (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008) illustrates the power of interorganizational collaboration and is a promising example of how a model can, as Fawcett and Desanto-Madeya (2013) have suggested, reduce conflict and facilitate communication within the profession, across professions, and with the public.

American Nurses Association

As the only full-service professional organization representing the interests of the 4 million RNs in the United States through its constituent and state nurses associations and its organizational affiliates, the ANA and its constituent organizations have also been active in developing documents that address advanced practice nursing. Two of these are particularly important for the contemporary conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing. Since 1980, the ANA has periodically updated its Social Policy Statement (ANA, 2010). Specialization has consistently been identified as a concept that differentiates advanced practice nursing from basic nursing practice. The most recent edition of the policy notes that specialization (“focusing on nursing practice in a specific area, identified from within the whole field of professional nursing”; ANA, 2010, p. 17) can occur at basic or advanced levels and that APRNs use additional specialized knowledge and skills obtained through graduate education in their practices. According to this statement, advanced nursing practice “builds on the competencies of the registered nurse and is characterized by the integration and application of a broad range of theoretical and evidence-based knowledge that occurs as part of graduate nursing education” (ANA, 2010, p. 18). In this document, APRNs are defined as RNs who hold master’s or doctoral degrees and are licensed, certified, and/or approved to practice in their roles by state boards of nursing or regulatory oversight bodies. APRNs are prepared through graduate education in nursing for one of four APRN roles (NPs, CRNAs, NMs, CNSs) and at least one of six population foci (family/individual across the life span, adult/gerontology, neonatal, pediatrics, women’s health/gender-related health, psychiatric/mental health; ANA, 2010). These definitions of specialization and advanced practice are consistent with the APRN Consensus Model.

The ANA also establishes and promulgates standards of practice and competencies for RNs and APRNs. Six standards of practice and 12 standards of professional performance are described in the fourth edition of Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice (ANA, 2021). Each standard is associated with competencies. Of the 18 total standards, all outline additional competencies for APRNs compared with RNs. For example, Standard 5, “Implementation,” addresses the consultation and prescribing responsibilities of APRNs and Standard 12, “Leadership,” addresses the competency that APRNs will model expert nursing practice to members of interprofessional teams and to consumers of health care. It is in the description of the competencies that APRN practice and the practice of nurses prepared in a specialty at the graduate level are differentiated from RN practice.

In addition to these documents, the ANA, together with the American Board of Nursing Specialties (ABNS), convened a task force on clinical nurse specialist competencies. For many reasons, including the recognition that developing psychometrically sound certifications for numerous specialties, especially for CNSs, would be difficult as the profession moved toward implementing the APRN Consensus Model, the ANA and ABNS convened a group of stakeholders in 2006 to develop and validate a set of core competencies that would be expected of CNSs entering practice, regardless of specialty (NACNS/National CNS Core Competency Task Force, 2010). This work and recent updates are discussed later in this chapter in the section on the NACNS.

American Association of Colleges of Nursing

Over the last 2 decades, the AACN has undertaken two nursing education initiatives aimed at transforming nursing education. In 2006 the AACN called for APRN preparation to be at the doctoral level in practice-based programs (DNP), with master’s-level education being refocused on generalist preparation (e.g., clinical nurse leaders, staff, and clinical educators). Clinical nurse leaders are not APRNs (AACN, 2021a) and therefore are not included in this discussion of conceptualizations. Through these initiatives, and to the extent that the AACN and Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education influence accreditation, the DNP is becoming the preferred degree for most APRNs. The growth of DNP education has advanced considerably. In 2006 there were 20 DNP programs; most recently in 2019 there were 348 DNP programs (AACN, 2019). Enrollments in and graduation from DNP programs have also risen substantially (AACN, 2019).

The DNP Essentials (AACN, 2006) were composed of eight competencies for DNP graduates. For APRNs, “Essential VIII specified the foundational practice competencies that cut across specialties and are seen as requisite for DNP practice” (AACN, 2006, p. 16). Recognizing that DNP programs also prepare nurses for non-APRN roles, the AACN acknowledged that organizations representing APRNs were expected to develop Essential VIII as it related to specific advanced practice roles and to “develop competency expectations that build upon and complement DNP Essentials 1 through 8” (AACN, 2006, p. 17). These Essentials affirmed that the advanced practice nursing core includes the “three Ps” (three separate courses)—advanced health/physical assessment, advanced physiology/pathophysiology, and advanced pharmacology—and is specific to APRNs. The specialty core must include content and clinical practice experiences that help students acquire the knowledge and skills essential to a specific advanced practice role. These requirements were reconfirmed in the Consensus Model (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008).

The DNP has been described as both a “disruptive innovation” (Hathaway et al., 2006) and a natural evolution for NP practice. The DNP has been endorsed as entry for APRN practice by three of the four professional association/organizations representing APRNs, with the exception of the ACNM (2019). As a result of national DNP discussions, APRN organizations have promulgated practice competencies that address doctorally prepared APRNs (e.g., ACNM, 2011b; NACNS, 2019). The NONPF (2012) now has one set of core competencies for NPs and developed population-based competencies for nurse practitioners (NONPF, 2013). Organizational positions on doctoral education are briefly explored in the discussion of APRN organizations later in this chapter.

Although not a conceptual model per se, the AACN’s publication The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education (2021b) represents a new approach to nursing education designed to provide consistency in graduate outcome. This framework conceptualizes the discipline of nursing via five key concepts: human wholeness, health, healing and well-being, environment–health relationship, and caring. It includes level 2 advanced-level nursing education subcompetencies designed to prepare nurses for advanced nursing practice specialty or advanced nursing practice roles, with specialty competencies designed to complement and build on level 2 competencies. These advanced-level nursing competencies are conceptualized to affirm a set of common competencies across APRN roles and are an important contribution to conceptual clarity about APRN practice in the United States. The Essentials provide guidance that DNP graduates attain and integrate level 2 competencies and subcompetencies for at least one APRN specialty or advanced nursing practice role and complete a scholarly project/project that the faculty will evaluate (AACN, 2021b). A discussion of APRN organizations’ conceptualization of APRN practice follows, along with a discussion of the extent to which their responses to the DNP influence conceptual clarity on advanced practice nursing.

National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties

The mission of the NONPF is to provide leadership in promoting quality NP education. Since 1990 the NONPF has fulfilled this mission in many ways, including the development, validation, and promulgation of NP competencies. As of 2012, there is only one set of NP core competencies (NONPF, 2012), along with recently added population-focused NP competencies (NONPF, 2013). A brief history of the development of competencies for NPs is presented here, in part because their development has influenced other APRN models.

In 1990 the NONPF published a set of domains and core competencies for primary care NPs based on Benner’s (1984) domains of expert nursing practice and the results of Brykczynski’s (1989) study of the use of these domains by primary care NPs (Price et al., 1992; Zimmer et al., 1990). Within each domain were a number of specific competencies that served as a framework for primary care NP education and practice.

After endorsing the DNP as entry-level preparation for the NP role, and consistent with the recommendations in the APRN Consensus Model (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008), new NP core competencies were developed in 2011 and amended in 2012, with core competency content developed in 2014 (NONPF, 2011 [amended 2012], 2014) and population-focused NP competencies added in 2013. Each of the nine core competencies is accompanied by specific behaviors that all graduates of NP programs, whether master’s or DNP prepared, are expected to demonstrate. Population-specific competencies for specific NP roles, together with the nine core competencies, are intended to inform curricula and ensure that graduates will meet certification and regulatory requirements.

From a conceptual perspective, these NP core and population-specific competency documents are notable for several reasons: (1) the competencies for NPs were developed collaboratively by stakeholder organizations; (2) empirical validation is used to affirm the competencies; (3) overall, the competencies are conceptually consistent with statements in the APRN Consensus Model, the DNP Essentials (AACN, 2006), and the ANA’s Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice 4th edition (ANA, 2021); and (4) the revised competencies are responsive to society’s needs for advanced nursing care and the contextual factors that will shape NP practice for at least the next decade. In the amended 2011 NONPF competencies (NONPF, 2011, 2012), there is an emphasis on practice that is not in the APRN Consensus Model (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008); patient-centered care, interprofessional care, and independent or autonomous NP practice, clearly responsive to healthcare reform initiatives, are addressed.

National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists

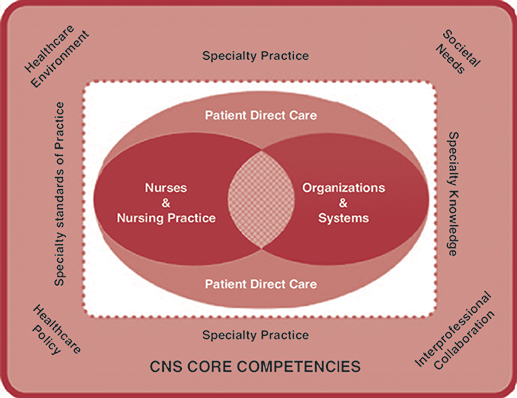

The NACNS originally published the Statement on Clinical Nurse Specialist Practice and Education in 1998, revised it in 2004, and updated it in 2019. While acknowledging the early conceptualization of CNS practice as subroles proposed by Hamric and Spross (1983, 1989), the 2019 version differentiated CNS practice from that of other APRNs, refined the competencies of the three spheres, and renamed the spheres of influence to the spheres of impact. These include patient direct care, nurses and nursing practice, and organizations and systems, each of which requires a unique set of competencies (NACNS, 2019; see Fig. 2.2). The statement also outlines expected outcomes (patient, nurse, and organization) of CNS practice within each sphere of impact and competencies.

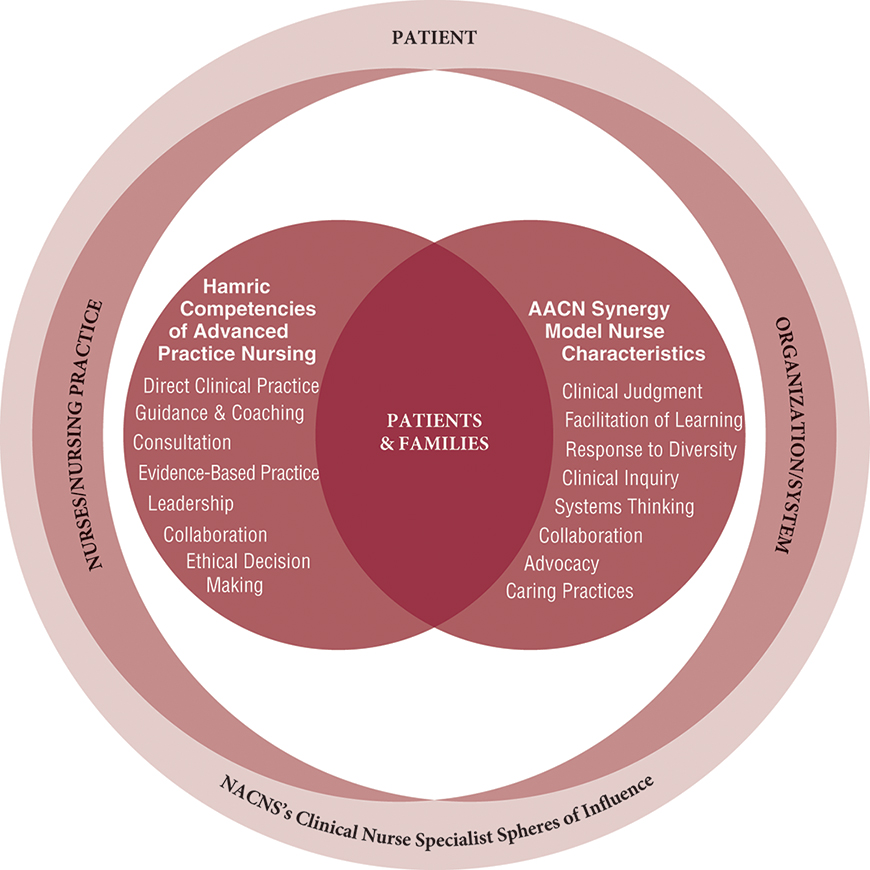

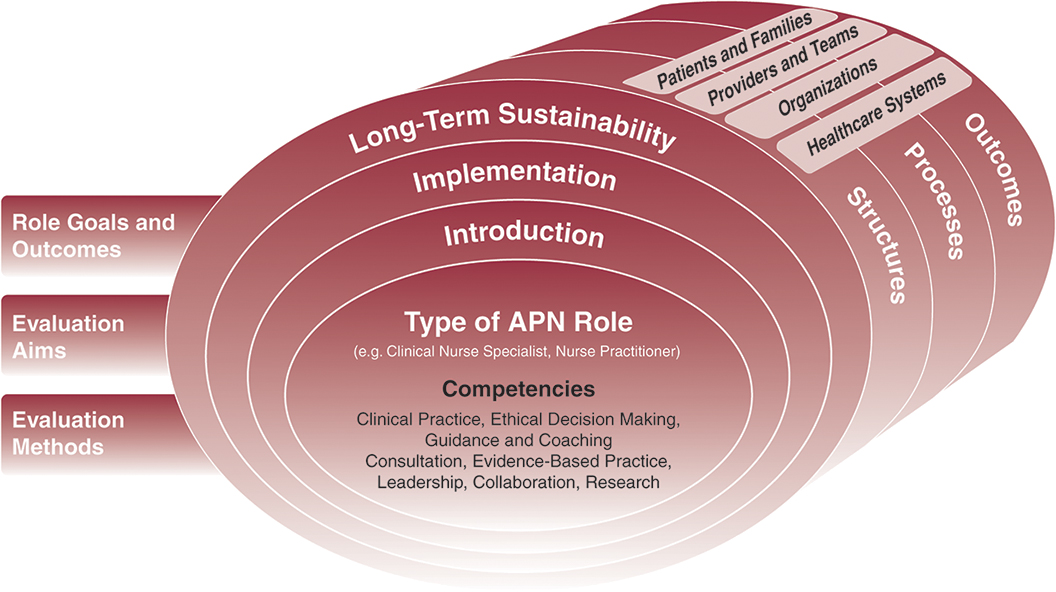

As work on the APRN Consensus Model neared completion, the NACNS and the APRN Consensus Work Group asked the ANA and the ABNS to “convene and facilitate the work of a National CNS Competency Task Force,” using a standard process to develop nationally recognized education standards and competencies (NACNS/National CNS Competency Task Force, 2010, p. 3). The process of developing and validating the competencies is described in the document. Fig. 2.3 illustrates the model of CNS competencies that emerged from this work, a synthesis of the NACNS’s spheres of influence (NACNS, 2004), Hamric’s seven advanced practice nursing competencies (Hamric, 2009), and the Synergy Model (Curley, 1998). Subsequently, new criteria for evaluating CNS education programs were developed, based on the competencies (Validation Panel of the NACNS, 2011). The APRN Consensus Model has affected certification for CNS roles more than any other APRN role.

Several key updates were included in the most recent statement (NACNS, 2019). It combined into a single document all competencies from the original statement on CNS practice and education and updated important aspects of the 2004 Statement. Additionally, the most recent statement updated the CNS model, changed the language to spheres of impact (replacing spheres of influence), enhanced the focus on the social mandate of the CNS, enhanced the integration with and of the APRN consensus model, and expanded references.

Initially the NACNS published a white paper describing a position of neutrality regarding the DNP as an option for CNS education (NACNS, 2005). However, in 2009, the NACNS did develop core competencies for doctoral-level practice, recognizing that some CNSs would pursue advanced clinical doctorates (NACNS, 2009). Three years later, the NACNS (2012) published a Statement on the APRN Consensus Model Implementation, outlining the importance of grandfathering currently practicing CNSs and monitoring the implementation of the Consensus Model to ensure that its adoption would not negatively affect the ability of CNSs to practice. To this end, the competencies outlined in the NACNS 2019 Statement on Clinical Nurse Specialist Practice and Education apply to CNSs with graduate preparation (master’s or doctorate) in nursing.

In June 2015, the NACNS issued a position statement endorsing the DNP as entry into practice for CNSs by 2030. Within this position statement, the NACNS stated support for “CNSs who pursued other graduate education to retain their ability to practice within the CNS role without having to obtain the DNP for future practice as an APRN after 2030” (NACNS, 2015, p. 2). For further information, see the NACNS website and Chapter 12.

American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology

CRNAs are recognized as APRNs within the APRN Consensus Model. Advanced practice competencies, as described in the DNP Essentials (AACN, 2006), the ANA Scope and Standards (ANA, 2021), and the APRN competencies identified in this text, are evident in the official statements of the AANA (2019, 2020). These statements include scopes of practice, standards for practice, and ethics. Chapter 16 provides a thorough discussion of CRNA practice.

The CRNA’s scope and standards of practice are defined in two separate documents from the AANA: Scope of Nurse Anesthesia Practice (2020) and Standards for Nurse Anesthesia Practice (2019). The Scope of Nurse Anesthesia Practice addresses the responsibilities of CRNAs, and the Standards for Nurse Anesthesia Practice describe standards of professional CRNA practice. The Scope document addresses the professional role; education, licensure, certification and accountability; clinical anesthesia practice; leadership, advocacy, and policymaking; and the future of nurse anesthesia practice. The purposes of the 14 Standards are to support the delivery of patient-centered, consistent, high-quality, and safe anesthesia care and assist the public in understanding the CRNA’s role in anesthesia care (AANA, 2019). The Scope of Nurse Anesthesia Practice and Standards for Nurse Anesthesia Practice provide descriptions of clinical competencies and responsibilities of CRNAs.

Initially, the AANA did not support the DNP for entry into CRNA practice and established a task force to evaluate doctoral preparation further. In 2019 the Council on Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational Programs revised its 2015 accreditation standards for nurse anesthesia education stating that students accepted into accredited entry-level programs on or after January 1, 2022, must graduate with doctoral degrees as of January 1, 2025. Further, Standard E.1 states, ”The curriculum is designed to award a DNP or Doctor of Nurse Anesthesia Practice to graduate students who successfully complete graduation requirements unless a waiver for this requirement has been approved by the Council” (Council on Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational Programs, 2019). The Council on Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational Programs (2019) also includes a requirement for the “three P” courses, consistent with requirements specified in the APRN Consensus document.

American College of Nurse-Midwives

Certified nurse-midwives (CNMs) are APRNs who are recognized in the APRN Consensus Model. Advanced practice competencies, described in the DNP Essentials (AACN, 2006), the ANA Scope and Standards (ANA, 2021), and the APRN competencies are apparent in the official statements of the ACNM (2011a, 2011c). These statements include scopes of practice, standards for practice, and ethics. Chapter 15 presents a thorough discussion of CNM practice.

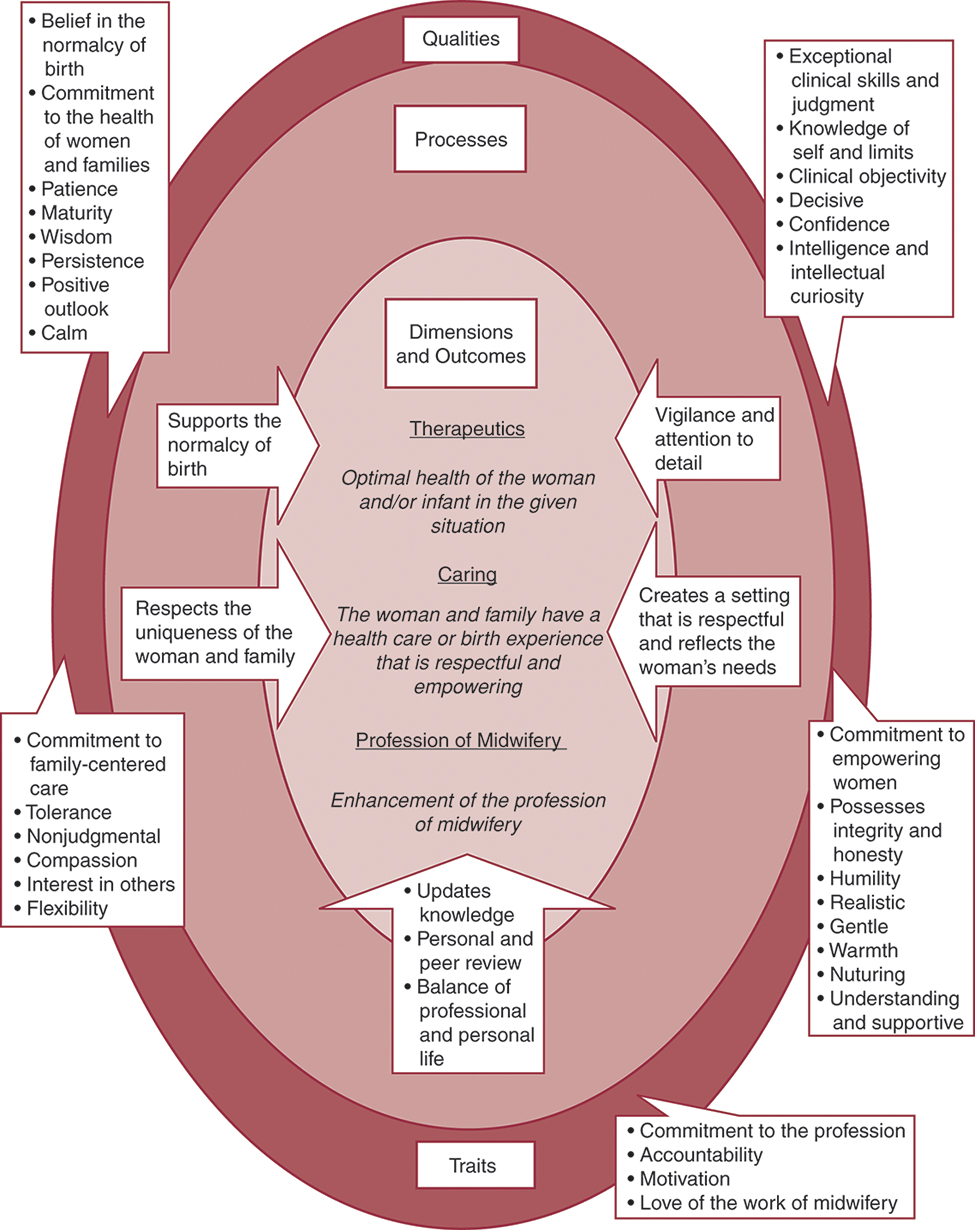

The scope of practice for CNMs (and certified midwives who are not nurses) has been defined in four ACNM documents: Definition of Midwifery and Scope of Practice of Certified Nurse-Midwives and Certified Midwives (ACNM, 2011a), the Core Competencies for Basic Midwifery Practice (ACNM, 2012a), Standards for the Practice of Midwifery (ACNM, 2011c), and the Code of Ethics with Explanatory Statements (ACNM, 2015a). The core competencies are organized into 16 hallmarks describing the art and science of midwifery and the components of midwifery care. The components of midwifery care include professional responsibilities, midwifery management processes, fundamentals, and care of women and of the newborn, within which are prescribed competencies. According to the definition, “CNMs are educated in two disciplines: nursing and midwifery” (ACNM, 2011a, p. 1). Competencies “describe the fundamental knowledge, skills and behaviors of a new practitioner” (ACNM, 2012a, p. 1). The hallmarks, components, and associated core competencies are the foundation on which midwifery curricula and practice guidelines are based.

In addition to the competencies, there are eight ACNM standards that midwives are expected to meet (ACNM, 2011c) and a code of ethics (ACNM, 2015a). The standards address issues such as qualifications, safety, patient rights, culturally competent care, assessment, documentation, and expansion of midwifery practice. Three ethical mandates related to the ACNM mission of midwifery to promote the health and wellbeing of women and newborns within their families and communities are identified in the ethics code.

As of 2010, CNMs entering practice must earn a graduate degree, complete an accredited midwifery program, and pass a national certification examination (see Chapter 15 for detailed requirements; ACNM, 2011a); the type of graduate degree is not specified. The ACNM does recognize the value of doctoral education as a valid and valuable path for CNMs, as evidenced by a statement on the practice doctorate in midwifery, including competencies (ACNM, 2011b). Although not cited, these competencies align with those in the DNP Essentials (AACN, 2006); the ACNM recognizes that there are other paths for a practice doctorate in midwifery. At the present time, the ACNM (2019) does not support the DNP as a requirement for entry into nurse-midwifery practice. Reasons cited are (1) midwifery practice is safe, based on the rigor of their curriculum standards and outcome data; (2) there is inadequate evidence to justify the DNP as a mandatory educational requirement for CNMs; and (3) the costs of attaining such a degree could limit the applicant pool and access to midwifery care (ACNM, 2012b, 2015b). Midwifery organizations have recently addressed the aspects of the 2008 Consensus Model that they support and identified those aspects that are of concern (ACNM et al., 2011).

International Organizations and Conceptualizations of Advanced Practice Nursing

In this section, issues of a common language and conceptual framework for advanced practice nursing are addressed. International perspectives on advanced practice nursing are covered more extensively in Chapter 5.

The ICN Nurse Practitioner/Advanced Practice Nursing Network (2020) defines a nurse practitioner/advanced practice nurse as “a registered nurse who has acquired the expert knowledge base, complex decision-making skills and clinical competencies for expanded practice, the characteristics of which are shaped by the context and/or country in which s/he is credentialed to practice.” A master’s degree is recommended for entry level (ICN Nurse Practitioner/Advanced Practice Nursing Network, 2020). Key concepts include educational preparation, the nature of practice, and regulatory mechanisms. The statement is necessarily broad, given the variations in health systems, regulatory mechanisms, and nursing education programs in individual countries.

In 2008 the CNA published Advanced Nursing Practice: A National Framework, which defined advanced nursing practice, described educational preparation and regulation, identified the two APRN roles (CNS and NP), and specified competencies in clinical practice, research, and leadership. In addition, they have issued position statements on advanced nursing practice (CNA, 2007) that affirm the key points in the national framework document and define and describe the roles and contributions to health care of NPs (CNA, 2009b) and CNSs (CNA, 2009a). In 2010 the CNA published a Core Competency Framework for NPs, which included the incorporation of theories of advanced practice nursing. The CNA (2019) published the Pan-Canadian framework for advanced practice nursing, which not only distinguishes the role of the CNS from that of the NP but also strengthens it and aligns it with ICN competencies.

Furthermore, leaders have undertaken an evidence-based, patient-centered, coordinated effort (called a decision support synthesis) to develop, implement, and evaluate the advanced practice nursing roles of the CNS and NP in Canada (DiCenso et al., 2010), a process different from the one used to advance these roles in the United States. This process included a review of 468 published and unpublished articles and interviews conducted with 62 key informants and four focus groups that included a variety of stakeholders. The purpose of this work was to “describe the distinguishing characteristics of CNSs and NPs relevant to Canadian contexts”; identify barriers and facilitators to effective development and use of advanced practice nursing roles; and inform the development of evidence-based recommendations that individuals, organizations, and systems can use to improve the integration of advanced practice nurses into Canadian health care (DiCenso et al., 2010, p. 21). The European Specialist Nurses Organisations (2015) defined 10 core (generic) competencies of CNS practice in Europe. The competencies address clinical role, patient relationship, patient teaching/coaching, mentoring, research, organization and management, communication and teamwork, ethics and decision making, leadership/policymaking, and public health. The competencies were developed to clarify the role of the CNS and include advanced knowledge in anatomy, physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology, similar to the APRN Consensus Model. It is expected that CNSs will collaborate with other health professionals to deliver high-quality patient care to ensure safety, quality of care, and equity of access to promote health and prevent disease.

Section Summary: Implications for Advanced Practice Nursing Conceptualizations

From this overview of organizational statements that clarify and advance APRN practice, it is clear that, nationally and internationally, stakeholders are actively defining advanced practice nursing. Progress in this area includes global agreement that this level of clinical nursing practice is advanced and builds on basic nursing education. As such, it requires additional education and is characterized by additional competencies and responsibilities. In the United States the consensus on an approach to APRN regulation was critical for the following reasons: (1) clarifying what an APRN is and the role of graduate education and certification in licensing APRNs, (2) ensuring that APRNs are fully recognized and integrated in the delivery of health care, (3) reducing barriers to mobility of APRNs across state lines, (4) fostering and facilitating ongoing dialogue among APRN stakeholders, and (5) offering common language regarding regulation.

Although there may not be unanimous agreement on the DNP as the requirement for entry into advanced practice nursing, the promulgation of the document fostered dialogue nationally and within APRN organizations on the clinical doctorate (whether or not it is the DNP) as a valid and likely path for APRNs to pursue. As a result, each APRN organization has taken a stand on the role of the clinical doctorate for those in the role and has developed or is developing doctoral-level clinical competencies. In doing so, it appears that the needs of their patients, members, other constituencies, and contexts have been considered. Until the time when a clinical doctorate becomes a requirement for entry into practice for all APRN roles, the development of doctoral-level competencies for APRN roles will help stakeholders distinguish between master’s- and clinical doctorate–prepared APRNs with regard to competencies.

Although important differences exist between roles and across countries, a common identity for APRNs resulting from policy and regulatory initiatives would facilitate communication within and outside the profession, consistent with assertions by Styles (1998) and Fawcett and Desanto-Madeya (2013) on the purposes of models. There are important differences among APRN organizations regarding such issues as doctoral preparation, which is also consistent with Fawcett and Desanto-Madeya’s assertion that there is not one best model.

The level of consensus regarding regulation in the United States reflects considerable and laudable progress, paving the way for policies and healthcare system transformations that will enable APRNs to be able to more fully ensure access to health care and improve its quality. The processes that have led to this juncture in the United States have required openness, civility, a willingness to disagree, and wisdom. Finally, there are at least two different approaches (collaborative policymaking in the United States and an evidence-based approach in Canada) to determine how best to assess contributions of APRNs and develop ways to integrate APRNs more fully into healthcare infrastructures in order to maximize their benefits to patients and populations. The global APRN community can examine these processes for insights on how to adapt them to suit their particular context.

The organizational models described address professional roles, licensing, accreditation, certification, education, competencies, and clinical practice. The descriptive statements about APRN roles and competencies demonstrate the common elements that exist across all APRN roles. These include a central focus on and accountability for patient care, knowledge and skills specific to each APRN role, and a concern for patient rights. The published definitions, standards, and competencies offer models against which similarities and differences among APRN roles and practices can be distinguished, educational programs can be developed and evaluated, and knowledge and behaviors can be measured for certification purposes. These will also assist practitioners to understand, examine, and improve their own practice and develop job descriptions. As advanced practice nursing moves forward in the United States and globally, the profession will continue to define situations in which a conceptual consensus, as well as alternative conceptualizations, will serve the public and the nursing profession.

CONCEPTUALIZATIONS OF THE NATURE OF ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING

The APRN role-specific models promulgated by professional organizations raise several questions, such as:

- ■ What is common across APRN roles?

- ■ Can an overarching conceptualization of advanced practice nursing be articulated?

- ■ How can one distinguish among basic, expert, and advanced levels of nursing practice?

Several authors have attempted to discern the nature of advanced practice nursing and address these questions. The extent to which all APRN roles are considered is not always clear; some only focus on CNS and NP roles.

Select frameworks are presented here that address the nature of advanced practice nursing. From the present review of a number of frameworks, the concepts of roles, domain, and competency are among those most commonly used to explain advanced practice nursing. However, meanings are not consistent. Hamric’s model (2014), which uses the terms roles and competencies, is the only one that is integrative—that is, it explicitly considers all four APRN roles. Because it is integrative, has remained relatively stable since 1996, has informed the development of the DNP Essentials (AACN, 2006) and CNS competencies, and is widely cited, it is discussed first, enabling the reader to consider the extent to which important concepts are addressed by other models. Otherwise, the models are discussed in chronologic order and include examples from both US and international conceptual models of APRN practice.

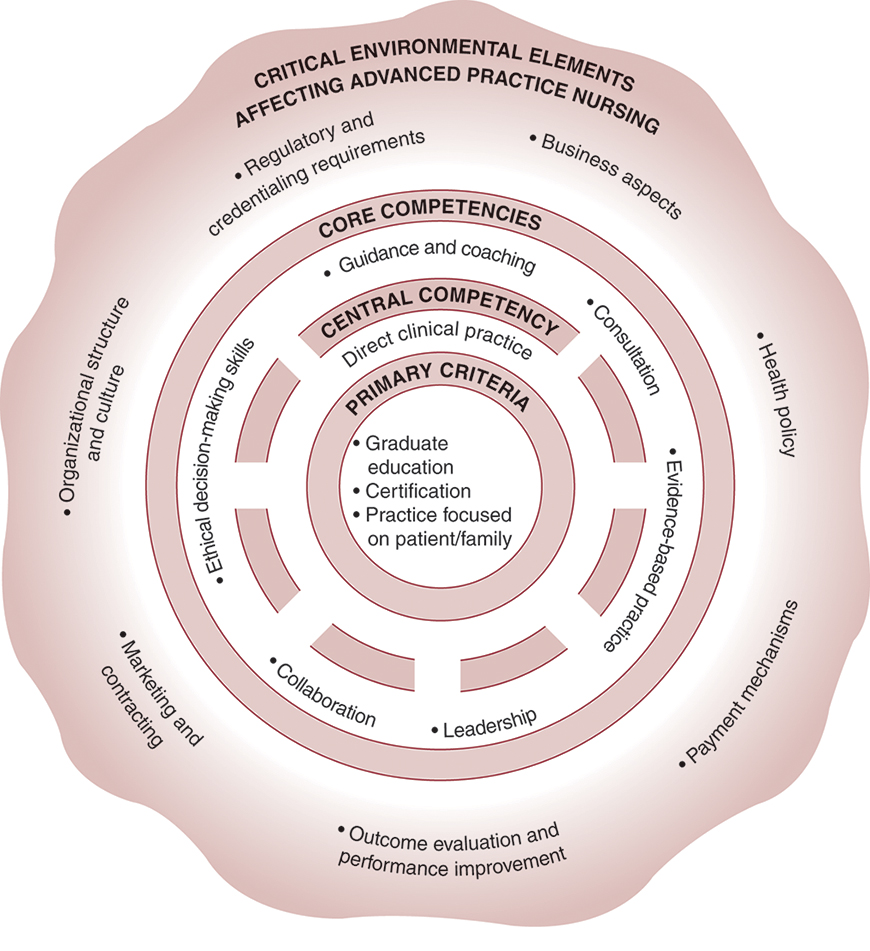

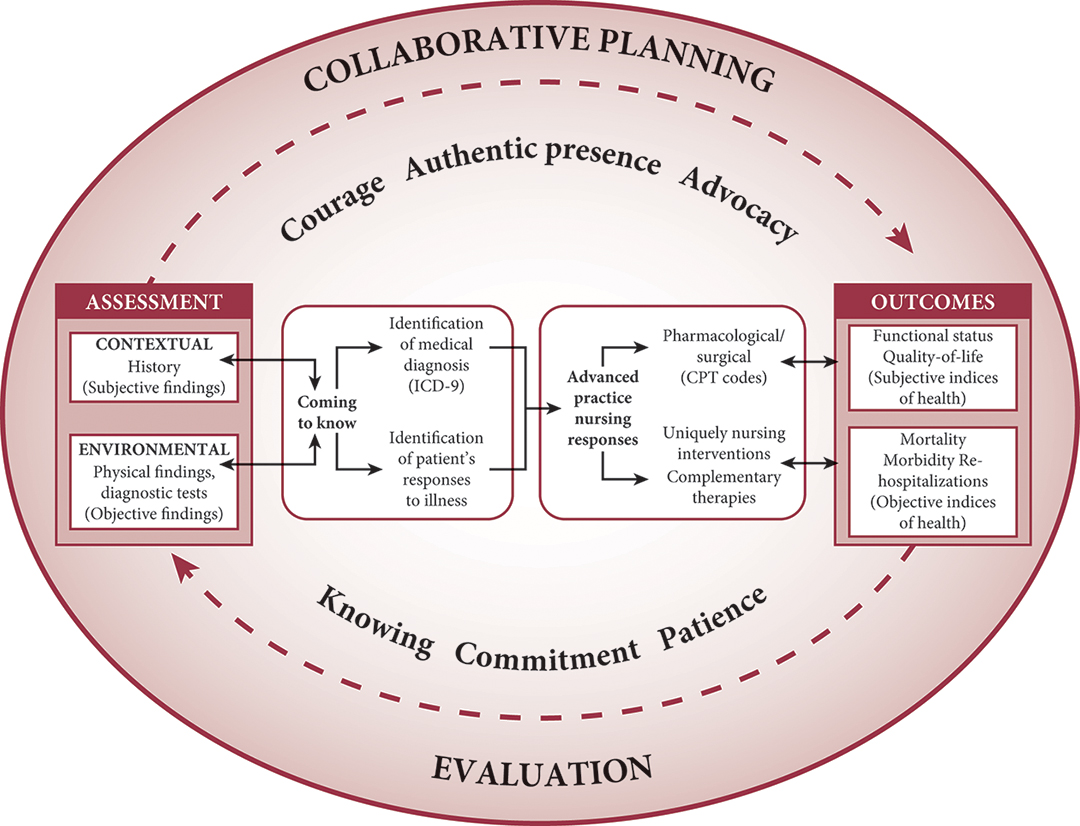

Hamric’s Integrative Model of Advanced Practice Nursing

One of the earliest efforts to synthesize a model of advanced practice that would apply to all APRN roles was developed by Hamric (1996). Hamric, whose early conceptual work was done on the CNS role (Hamric & Spross, 1983, 1989), proposed an integrative understanding of the core of advanced practice nursing, based on literature from all APRN specialties (Hamric, 1996, 2000, 2005, 2009, 2014; see Chapter 3). Hamric proposed a conceptual definition of advanced practice nursing and defining characteristics that included primary criteria (graduate education, certification in the specialty, and a focus on clinical practice with patients) and a set of core competencies (direct clinical practice, collaboration, guidance and coaching, evidence-based practice, ethical decision making, consultation, and leadership). This early model was further refined, together with Hanson and Spross in 2000 and 2005 (Hamric, 2000, 2005), based on dialogue among the editors. Key components of the original model (Fig. 2.4) include the primary criteria for advanced nursing practice, seven advanced practice competencies with direct care as the core competency on which the other competencies depend, and environmental and contextual factors that must be managed for advanced practice nursing to flourish.

The revisions to Hamric’s original model highlight the dynamic nature of a conceptual model, and that essential features remain the same (Chapter 3, Fig. 3.4). Models are refined over time according to changes in practice, research, and theoretical understanding. The inherent stability and robustness of Hamric’s model are noteworthy, particularly in light of the many potentially transformative advanced practice nursing initiatives being developed. This model forms the understanding of advanced practice nursing used throughout this text and has provided the structure for each edition of the book. Hamric’s model has been used by contributors to this text to further elaborate specific competencies such as guidance and coaching (see Chapter 7) and ethical practice (see Chapter 11). It has also informed the development of the DNP Essentials (AACN, 2006) and the revised CNS competencies and is widely cited in the advanced practice literature, which provides further evidence of its contribution to conceptualizing advanced practice nursing.

In addition, integrative literature reviews provide further support for Hamric’s integrative conceptualization of advanced practice nursing. Mantzoukas and Watkinson’s (2007) literature review sought to identify “generic features” of advanced nursing practice; seven generic features were identified (see Box 2.2).

The first three generic features are consistent with the direct care competency in Hamric’s model; these three characteristics seem directly related to clinical practice, which supports direct care as a central competency. The remaining four features are consistent with the three competencies of leadership, guidance and coaching, and evidence-based practice in Hamric’s model.

Similarly, an integrative literature review of CNS practice by Lewandowski and Adamle (2009) affirmed the direct care, collaboration, consultation, systems leadership, and coaching (patient and staff education) competencies in Hamric’s model. Ten countries were represented in their review, and their findings were organized using the NACNS’s three spheres of influence (since reconceptualized/relabeled as spheres of impact). Within the first sphere, management of complex or vulnerable populations, they found three essential characteristics—expert direct care, coordination of care, and collaboration. In the sphere of educating and supporting interdisciplinary staff, substantive areas of CNS practice were education, consultation, and collaboration. Within the system sphere, CNSs facilitate innovation and change. These findings lend support for the integration of Hamric’s model with the NACNS model of CNS core competencies (NACNS, 2019; NACNS/National CNS Competency Task Force, 2010).

Conceptual Models of APRN Practice: United States Examples

Fenton’s and Brykczynski’s Expert Practice Domains of the CNS and NP

Some of the early work describing the practice domains of APRNs (CNSs and NPs) was conducted by Fenton (1985) and Brykczynski (1989), using Benner’s model of expert nursing practice (Benner, 1984). To fully appreciate their contributions to the understanding of advanced practice, it is important to highlight some of Benner’s key findings about nurses who are experts by experience. Although Benner’s seminal work, From Novice to Expert (1984), has been used in the conceptualization of advanced practice nursing, it is important to note that Benner has not studied advanced practice nurses; her model was based on the expert practice of clinical nurses. Fenton’s and Brykczynski’s studies represent an extension of Benner’s findings and theories to advanced practice nursing.

The early work of Benner and associates informed the development of the first NONPF competencies, graduate curricula in schools of nursing, models of practice, and the standards for clinical promotion. A noted contribution of this early work was that it “put into words what they had always known about their clinical nursing expertise but had difficulty articulating” (Benner et al., 2009, p. xix). It is perhaps this impact that led to the sustained integration of Benner’s studies of experts by experience into the APRN literature, including descriptions and development of competencies.

Through the analysis of clinical exemplars discussed in interviews, Benner (1984) derived a range of competencies that resulted in the identification of seven domains of expert nursing practice. Within this lexicon, these domains are a combination of roles, functions, and competencies, although the three were not precisely differentiated. The seven domains are the helping role, administering and monitoring therapeutic interventions and regimens, effective management of rapidly changing situations, diagnostic and monitoring function, teaching and coaching function, monitoring and ensuring the quality of healthcare practices, and organizational and work role competencies.

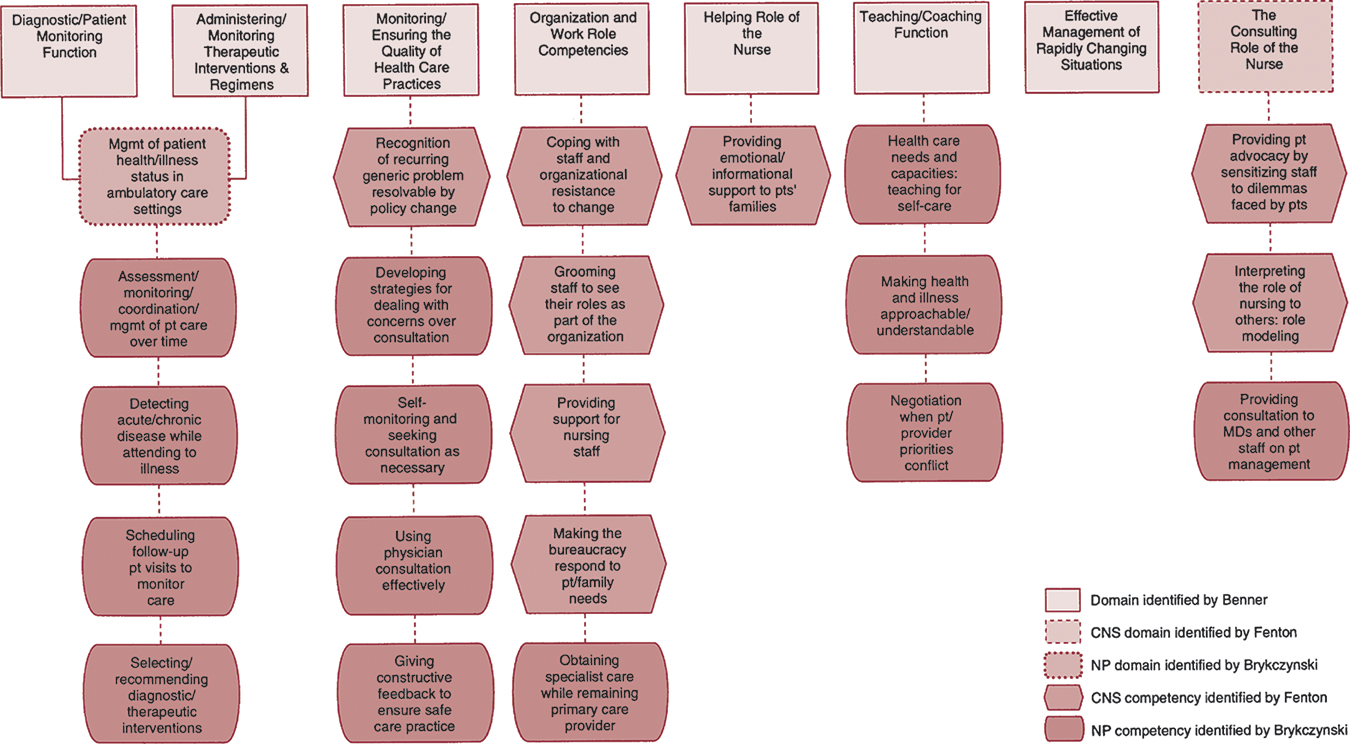

Fenton (1985) and Brykczynski (1989) each independently applied Benner’s model of expert practice to APRNs, examining the practice of CNSs and NPs, respectively. Fenton and Brykczynski (1993) jointly compared their earlier research findings to identify similarities and differences between CNSs and NPs. They verified that nurses in advanced practice were indeed experts, as defined by Benner, showing they were experts by more than experience alone. They identified additional domains and competencies of APRNs (Fig. 2.5). Across the top of Fig. 2.5 are the seven domains identified by Benner and the additional domain found in CNS practice (Fenton, 1985), that of consultation provided by CNSs to other nurses (rectangular dotted box, top right). Under this box are two new CNS competencies (hexagonal boxes). The third (rounded) box is a new NP competency identified by Brykczynski in 1989. In this study of NPs, Brykczynski identified an eighth domain (the management of health and illness in ambulatory care settings) and recognized it as a qualitatively different expression from the first two domains identified by Benner. For NPs, the new competencies were a result of the integration of the diagnostic–monitoring and administering–monitoring domains.

The figure also reveals new CNS and NP competencies identified by Fenton and Brykczynski’s work. New CNS competencies were identified under the organization and work role domain (e.g., providing support for nursing staff) and the helping role, in addition to the consulting domain and competencies. New NP competencies were noted in seven of the eight domains (e.g., detecting acute or chronic disease while attending to illness under the diagnostic–administering domains). By examining the extent to which APRNs demonstrate the seven domains found in experts by experience and uncovering differences, the findings offer insight into the differences between expert and advanced practice. In addition, Fenton and Brykczynski’s work described ways in which the CNS and NP roles may differ with regard to practice domains and competencies.

These early findings suggest that a deeper understanding of advanced practice could be beneficial to understanding and conceptualizing advanced nursing practice. Benner’s methods could be applied to studies of advanced practice nursing, with the following aims: (1) to confirm Fenton and Brykczynski’s findings in CNS and NP roles and identify new domains and competencies across all four APRN roles, (2) to understand how APRN competencies develop in direct-entry graduate and RN graduate students, and (3) to compare the non-master’s-prepared clinician’s competencies with the APRN’s competencies to distinguish components of expert versus advanced practice nursing. Studies focused on how APRNs acquire expertise in APRN and interprofessional competencies could inform future conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing.

Calkin’s Model of Advanced Nursing Practice

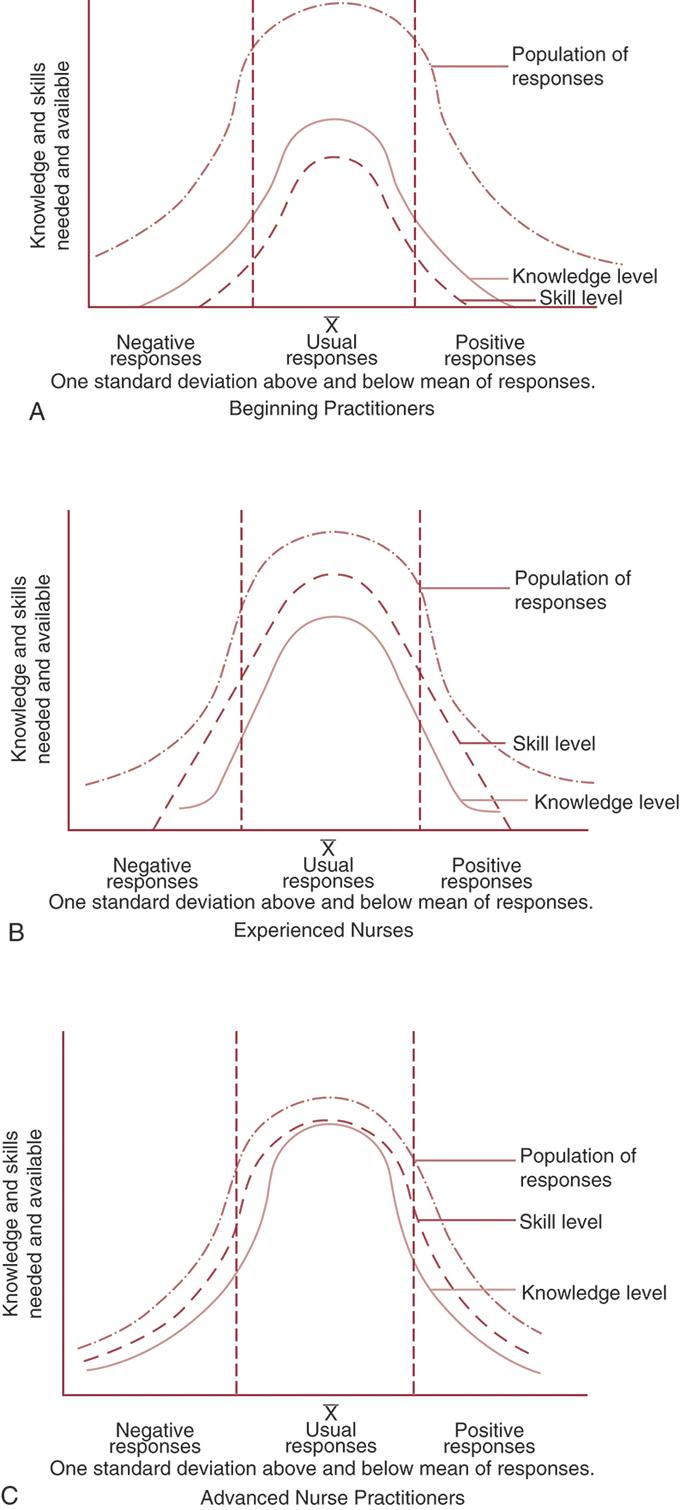

Calkin’s model (1984) was the first to explicitly distinguish the practice of experts by experience from advanced practice nursing of CNSs and NPs. Calkin developed the model to help nurse administrators differentiate advanced practice nursing from other levels of clinical practice in personnel policies. The model proposed that this could be accomplished by matching patient responses to health problems with the skill and knowledge levels of nursing personnel. In Calkin’s model, three curves were overlaid on a normal distribution chart. Calkin depicted the skills and knowledge of novices, experts by experience, and APRNs in relation to knowledge required to care for patients whose responses to healthcare problems (i.e., healthcare needs) ranged from simple and common to complex and complicated (Fig. 2.6). A closer look at Fig. 2.6A shows that patients have many more human responses (the highest and widest curve) than a beginning nurse would have the knowledge and skill to effectively manage. The impact of experience is illustrated in Fig. 2.6B. The highest and widest curve is effectively the same, but because of experience, expert nurses have more knowledge and skill. However, although the curves are higher and somewhat wider, the additional skill and knowledge of expert nurses do not yet match the range of responses they may encounter in the patients. In Fig. 2.6C, APRNs, by virtue of education and experience, do possess the knowledge and skills that enable them to respond to a wider range of human responses. The three curves in Fig. 2.6C are parallel to each other, suggesting that even as less common human responses arise in clinical practice, APRNs are able to creatively and effectively respond to these unusual problems because of their advanced knowledge and skills.

Calkin (1984) used the framework to explain how APRNs perform under different sets of circumstances—when there is a high degree of unpredictability, new conditions, new patient populations, or new sets of problems and a wide variety of health problems requiring the services of “specialist generalists.” What APRNs do in terms of functions was also defined. For example, when patients’ health problems elicit a wide range of human responses with continuing and substantial unpredictable elements, the APRN should do the following (Calkin, 1984):

- ■ Identify and develop interventions for the unusual by providing direct care.

- ■ Transmit this knowledge to nurses and, in some settings, to students.

- ■ Identify and communicate the need for research or carry out research related to human responses to these health problems.

- ■ Anticipate factors that may lead to unfamiliar human responses.

- ■ Provide anticipatory guidance to nurse administrators when the changes in the diagnosis and treatment of these responses may require altered levels or types of resources.

A principal advantage of Calkin’s model is that the skills, education, and knowledge needed by nurses are considered in relation to patient needs. It provides a framework for scholars to use in studying the function of APRNs in a variety of practice situations and should be a useful conceptualization for administrators who must maximize a multilevel interprofessional workforce and need to justify the use of APRNs. In today’s practice environments, this conceptualization could be modified and applied in other settings based on whether a situation requires an APRN or RN and which mix of intra- and interprofessional staff and support staff is needed when settings have a high degree of predictability versus those that have high clinical uncertainty.

The model has been left for others to test. Although Calkin’s thinking remains relevant, no new applications of the work were found. However, Brooten and Youngblut’s work (2006) on the concept of “nurse dose,” based on years of empirical research, offers a similar understanding of the differences among beginners, experts by experience, and APRNs. They proposed, as did Calkin (1984), that one needs to understand patients’ needs and responses and the expertise, experience, and education of nurses to match nursing care to the needs of patients, but they did not cite Calkin’s work. Similarly, the Synergy Model in critical care is based, in part, on an understanding of patient and nurse characteristics consistent with Calkin’s ideas (Curley, 1998).

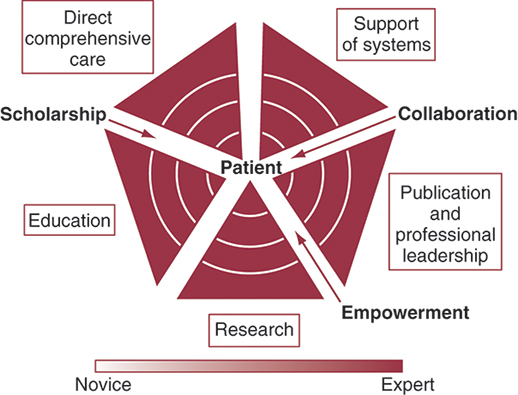

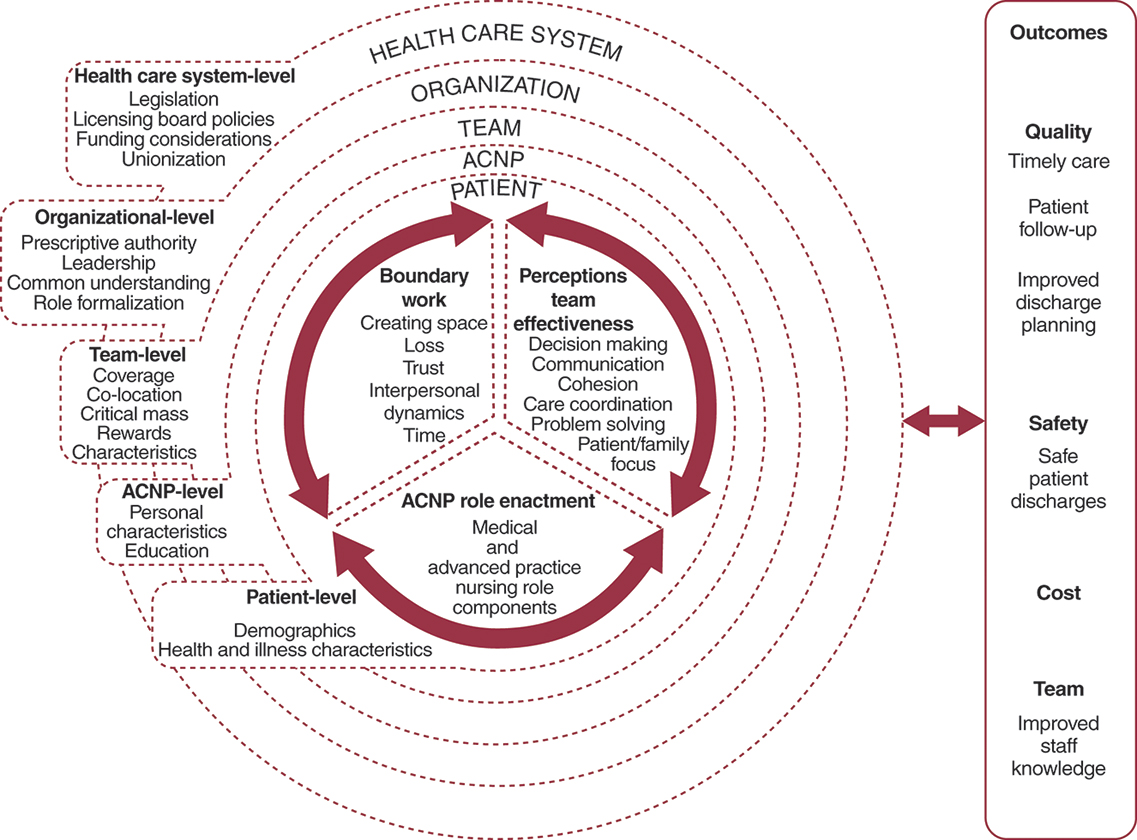

Strong Memorial Hospital’s Model of Advanced Practice Nursing

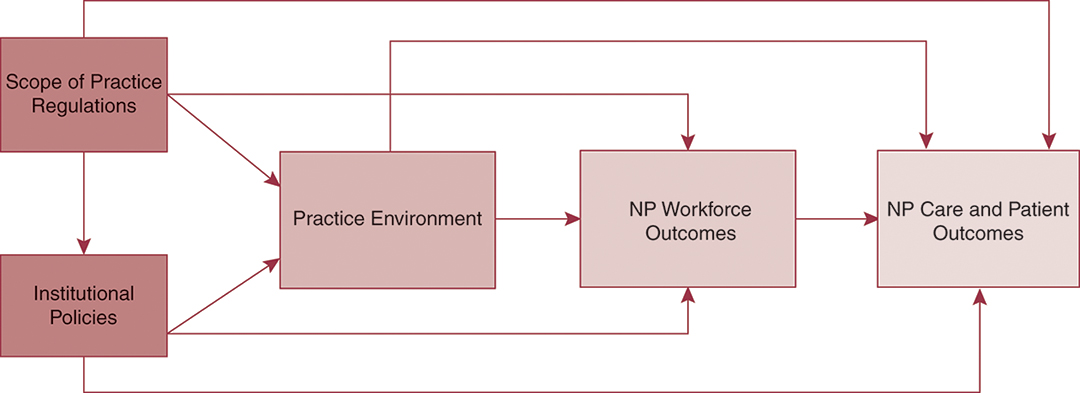

APRNs at Strong Memorial Hospital, Rochester, New York developed a model of advanced practice nursing (Ackerman et al., 1996, 2000; Mick & Ackerman, 2000). The model evolved from the delineation of the domains and competencies of the acute care NP (ACNP) role, conceptualized as a role that “combines the clinical skills of the NP with the systems acumen, educational commitment, and leadership ability of the CNS” (Ackerman et al., 1996, p. 69). The five domains are direct comprehensive patient care, support of systems, education, research, and publication and professional leadership. All domains have direct and indirect activities associated with them. In addition, three unifying threads influence each domain: collaboration, scholarship, and empowerment, which are illustrated as circular and continuous threads (Ackerman et al., 1996; Fig. 2.7). These threads are operationalized in each practice domain. Ackerman et al. (2000) noted that the model is based on an understanding of the role development of APRNs; the concept of novice (APRN) to expert (APRN) is foundational to the Strong model.